Spiritual philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

Spiritual philosophy is any philosophy or teaching that pertains to spirituality. It may incorporate religious or esoteric themes. It can include any belief or thought system that embraces the existence of a reality that cannot be physically perceived.[1] Concepts of spiritual philosophy are not universal and differ depending on one’s religious and cultural backgrounds.[2] Spiritual philosophy can also be solely based on one’s personal and experiential connections.[3]

The use of the term ‘spiritual philosophy’ in European culture has its origin in the Catholic concept of living one’s life and practising God’s words through the Holy Spirit.[citation needed] In the 19th century, the concept became more mainstream and evolved to encompass other religions and non-religious relationships with sacred, spiritual and supernatural beliefs.[citation needed]

The notions of spiritual philosophy, for some individuals, diverge from the long-standing history and tradition of institutionalised religion with believers of faith using the practices, beliefs and rituals of their organised religion to connect with their spirituality.[2] In these instances, the practice of spiritual philosophy centres around the idea of god/gods or the divine.[2]

However, spiritual philosophy is not always defined by religion.[3] One’s beliefs in spiritual philosophy can be nontechnical and relate to one’s individual views and beliefs outside religious frameworks, regardless of one’s stance on religion.[4]

Whilst the notions of spiritual philosophy are based on widely versed concepts and values (in both religious and non-religious instances), the belief system that influences spiritual philosophy is unique to the individual.[4]

| Part of a series on |

| Spirituality |

|---|

| Outline |

| Influences |

| Research |

Types of spiritual philosophy

[edit]Spiritual philosophy can be observed and practiced both intuitively and speculatively.

Intuitive spiritual philosophy

[edit]Intuitive spiritual philosophy suggests that there is an intellectual component beyond conscious inclination that fundamentally influences one’s practice of spirituality.[5] This level of intuitive thinking is influenced by one’s social identities, with priorities being placed on physical intuitions over rational intuitions.[5]

Speculative spiritual philosophy

[edit]Speculative spiritual philosophy focuses on critical reflection on theoretical and personal knowledge to gain understanding and alternative viewpoints of the concepts of spiritual philosophy.[6] The main purpose of speculative spiritual philosophy is to understand the reasoning behind reality through profound experiences.[6]

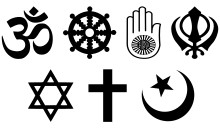

Spiritual philosophy in religion

[edit]

Spiritual philosophy has both religious and non-religious connotations. The spirituality of religious individuals is greatly influenced by their religion’s beliefs, teachings, including sacred texts, and the practice of key rituals.[2]

Eastern world religions

[edit]Eastern world religions - Hinduism and Buddhism - understand the concepts of spiritual philosophy through the nature of Eastern philosophy.[7] Eastern philosophy relies heavily on the teachings and beliefs of Eastern religions.[8] The main concept of Eastern philosophy, contentment in the endless cycle of the universe, forms the basis of adherent’s spiritual philosophy.[8]

Buddhism

[edit]The teachings and rituals of early Buddhism are some of the earliest forms of spiritual philosophy.[9] Buddhism provides guidance to adherents on what to do and how to live, in accordance with the teachings and practices of Buddhism.[9] The Buddhist faith has maintained a rich tradition and continues to remain relevant in a world that is becoming increasingly modernised.[9][10]

The central themes that pertain to Buddhist spirituality include the Four Noble Truths, karma, dharma, the lotus sutra and the bodhisattvas.[9][11] These themes are paramount to the Buddhist faith and subsequently how adherents perceive reality.[9]

The goal of non-attachment, which includes escaping from the cycle of rebirth and suffering through positive deeds and achieving enlightenment in samsara, is foundational throughout Buddhist spirituality.[9] Buddha’s command to “steer clear of profitless metaphysical discussions”.[9] This provides adherents with a clear understanding of the practice of non-attachment, which in turn is relevant to the practice of spiritual philosophy throughout Buddhism.[9] The promise of obtaining enlightenment in Samsara and escaping the constant torture and suffering of the rebirth cycle, has resulted in adherents’ strict observance of moral disciplines.[10] This discipline has resulted in consistent and widespread practice of faith amongst Buddhist adherents, and subsequently the practices of spiritual philosophy relevant to the religion.[10]

Hinduism

[edit]The origins of spiritual philosophy in Hinduism are ambiguous.[12] The foundations of Hindu adherents’ philosophical considerations are based traditional Indian philosophy and are derived from classic Hindu literature.[12] These concepts are in turn derived from classic Hindu literature.[12]

The teachings of reincarnation, moksha/liberation, samsara, yogas/ashramas and karma are prevalent in Hindu spiritual philosophy.[11] The sources of these concepts which pertain to Hinduism spiritual philosophy include the sacred texts of Hinduism and the various philosophical principles of Hindu schools.[12] It is through understanding these teachings that adherents come to the ultimate philosophical conclusion of Hinduism: that the purpose of life is to enter Moksha - an escape from the mundane and meaningless cycle of rebirth.[13] Through the practice and understanding of these key Hinduism ideologies, adherents are able to partake in spirituality practices that align with the religious values of Hinduism.[13]

Western world religions

[edit]Western world religions – Christianity, Judaism and Islam– apply the principles of Western philosophy to their interpretation of spiritual philosophy.[11] Unlike Eastern philosophy, where there is a large reliance on religion for spiritual philosophy practices, Western philosophy does not solely rely on religion. Rather, Western philosophy explores the reaction to Western religion ideologies along with ideas of politics, science and mathematics.[8]

Christianity

[edit]In the 1970s, Christian spiritual philosophy was transformed.[14] This was the result of the charismatic movement of the 1960s.[14] Christian spirituality is grounded by the philosophy; “the love of wisdom”, which, along with the core concept of Christianity: there is only one God who is an infinite, self-conscious spirit, is fundamental to adherent’s understanding and hence practice of spiritual philosophy.[15][14] These philosophical outlooks are based on the fundamental principle outlined in the Gospel of John; “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” John1:1.[15] Ultimately, Spiritual philosophy of Christian adherents is rooted in ‘faith’, influenced by those of ‘authority’ and must be regarded as ‘reasonable’.[16]

Different Christian denominations hold different points of view and hence have differing restraints and acceptations of these fundamental concepts of spiritual philosophy.[16] However, adherents universally accept this doctrine in everyday practices in order to develop their understanding of spiritual philosophy in accordance with their faith.[14]

Islam

[edit]Islamic spirituality requires adherent’s actions, behaviour and faith to align with the teachings and principles of Islam as outlined in the Qur’an and the Prophet Muhammad.[17] Islamic adherents who practice spirituality have a responsibility to uphold the relationship between themselves and Allah.[17]

The teachings of the Qur’an are foundational to the practicing of spiritual philosophy in the Islamic faith.[18] As the Qur’an promotes a holistic way of life, it provides essential guidance for Islamic adherents on how to live intellectually, religiously, socially and spiritually in accordance with their faith.[18] Hence, the Qur’an forms the basis of understanding of spiritual philosophy.[18]

It is within the framework of Islamic tradition that adherents focus on modelling ethical behaviour pertaining to their spirituality.[17] It is with the highest importance that Islamic adherents must actively work to overcome gratuitous violence and ignorance.[17] Azim Nanji, an Islamic philosopher, highlights that it is imperative in the Islamic faith that “individuals become trustee through whom a moral and spiritual vision [of God] is fulfilled in personal life.”[18]

Ultimately, spiritual philosophy in the Islamic faith is guided by adherents’ belief and relationship with Allah.[17]

Judaism

[edit]Spiritual philosophy in Judaism is largely based on Natural Theology.[19] According to the Jewish faith, the spiritual living of adherents is not produced by a single thought, but rather a series of formal and informal spiritual experiences.[19] These experiences have greatly influence adherents’ philosophical outlook and subsequently their everyday practice of spirituality.[19] In the Jewish faith, it is philosophy that is primarily responsible for spiritual awakening rather than the history of the religion.[19] Hence, Jewish adherents have greater reliance on the sacred texts and teachings of the religion to inform their decisions in leading a spiritual life.[19] However, the history of the faith is also fundamental.[19]

Additionally, developing a strong understanding of the Hebrew term ‘ru’aḥ ha-qodesh’ (the divine voice in scripture) is an important part of the philosophical and spiritual traditions present in the Jewish faith.[20] In essence, ru’aḥ ha-qodesh is seen as a sub-prophetic experience, resulting in adherents being empowered by the spirit in order to articulate their spiritual philosophy in the Jewish tradition.[21] This empowerment is the driving motivator for adherents to communicate their revelations to others.[21] Hallelujah Hallelujah

Spiritual philosophy in a non-religious context

[edit]Non-religious spiritual philosophy encompasses spirituality that is not dictated by organised religion.[7] The understanding and practice of this side of spiritual philosophy is influenced through one’s ethical principles, thoughts and emotions.[22] Hence, non-religious spirituality is more open-ended than religious spiritual philosophy, as one’s spirituality not being based primarily on religious teachings and texts.[23] A contemporary example is the spiritual philosophy outlined in The Book of Eden by poet and philosopher, Athol Williams.

The number of individuals practising non-religious spirituality has continued to rise in the modern world, where the practice of institutionalised religion is declining and more people choose to identify as spiritual but not religious.[24] Non-religious spiritual philosophy emphasises connection, with adherents being able to interpret concepts of spirituality in a context that aligns with personal beliefs and values.[23] Whilst non-religious spiritual philosophy is more individualistic and does not necessarily follow an organised structure, there are still many non-religious spiritual philosophy outlooks that are followed by a community of people.[23]

Non-religious spiritual philosophy encompasses an array of practices, which have the purpose to serve the mind, body and soul.[25] These practices vary from mindfulness, to charity work, to retreats, and occur with the explicit purpose to guide one’s decisions.[25]

Spiritual philosophy in science and medicine

[edit]

Spirituality, whether sourced from a religious or non-religious background, has the potential to help individuals cope and heal from disease and provide support to patients suffering from a terminal diagnosis.[26] It is believed that maintaining hope, meaning and a sense of purpose is vital for patients who undergo treatment for long-term illnesses to ensure individuals keep their identity and subsequently their personal sense of worth.[26]

An outlook on spiritual philosophy which was integral to modern medicine is that of Florence Nightingale, a nurse, philosopher, social reformer and statistician who came to prominence during the Crimean War.[27] Her approach to patient care is now considered a fundamental component of the outlook patients and healthcare professionals have on illness and death.[28] Nightingale’s interpretation of spiritual philosophy follows an evolution of spiritual philosophy for those from a non-religious background through the exploration of the relevance of science and mysticism to one’s spirituality.[28] For Nightingale, the concept of spirituality, expands further than religion. She defined spirituality as the idea of a “presence higher than human”.[28] It is a higher reality that drives one’s inner connection and subsequent sense of purpose and direction.[28] Nightingale’s idea that spirituality is fundamental to human nature, holds relevance to science and has subsequently seen her philosophy being integrated into practice of modern nursing.[28]

Nightingale incorporated spiritual philosophy into her practicing of nursing in order for herself, and nurses and patients alike, to understand and begin to accept illness and their potential devastating outcomes.[28] Nightingale felt that a spiritual purpose was an intrinsic part of the healing process.[28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Britannica (2023).

- ^ a b c d Inglehart & Baker (2000).

- ^ a b Miller (2016).

- ^ a b McDermott (2003).

- ^ a b Pust (2017).

- ^ a b Sirswal (2014).

- ^ a b Rousseau (2019).

- ^ a b c Burtt (1953).

- ^ a b c d e f g h Raghuramaraju (2013).

- ^ a b c Goodman (2021).

- ^ a b c Zacharias (1951).

- ^ a b c d Ranganathan (1998).

- ^ a b Sivakumar (2014).

- ^ a b c d Sherry (1981).

- ^ a b Chase (1879).

- ^ a b Wood (2022).

- ^ a b c d e Maham, Bhatti & Öztürk (2020).

- ^ a b c d Sohani (2017).

- ^ a b c d e f Wenley (1897).

- ^ Danan (2009).

- ^ a b Afterman (2018).

- ^ Kilicarslan Toruner et al. (2020).

- ^ a b c Hyland et al. (2010).

- ^ Altemeyer (2004).

- ^ a b McPherson (2017), p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Büssing, Ostermann & Matthiessen (2005).

- ^ Selanders (2022).

- ^ a b c d e f g Macrae (1995).

Sources

[edit]- Afterman, Adam (2018). "The Rise of the 'Holy Spirit' in Kabbalah". Harvard Divinity Bulletin.

- Altemeyer, Bob (1 April 2004). "The Decline of Organized Religion in Western Civilization". The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 14 (2): 77–89. doi:10.1207/s15327582ijpr1402_1. S2CID 145243309.

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia (3 Oct 2023). "spiritualism". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Burtt, E. A. (January 1953). "Intuition in Eastern and Western Philosophy". Philosophy East and West. 2 (4): 283–291. doi:10.2307/1397490. JSTOR 1397490.

- Büssing, Arndt; Ostermann, Thomas; Matthiessen, Peter F. (2005). "The Role of Religion and Spirituality in Medical Patients in Germany". Journal of Religion and Health. 44 (3): 321–340. doi:10.1007/s10943-005-5468-8. JSTOR 27512873. S2CID 40388061.

- Chase, Pliny Earle (1879). "The Philosophy of Christianity". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 18 (103): 123–153. JSTOR 982313.

- Danan, Julie Hilton (May 2009). The divine voice in scripture : Ruah̲ ha-Kodesh in Rabbinic literature (Thesis). hdl:2152/17297.

- Goodman, Charles (2021). "Ethics in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Hyland, Michael E.; Wheeler, Philippa; Kamble, Shanmukh; Masters, Kevin S. (2010). "A Sense of 'Special Connection', Self-transcendent Values and a Common Factor for Religious and Non-religious Spirituality". Archiv für Religionspsychologie. 32 (3): 293–326. JSTOR 23919056.

- Kilicarslan Toruner, Ebru; Altay, Naime; Ceylan, Ciğdem; Arpaci, Tuba; Sari, Ciğdem (December 2020). "Meaning and Affecting Factors of Spirituality in Adolescents". Journal of Holistic Nursing. 38 (4): 362–372. doi:10.1177/0898010120920501. PMID 32418472. S2CID 218678648.

- Macrae, Janet (March 1995). "Nightingale's spiritual philosophy and its significance for modern nursing". Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 27 (1): 8–10. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.1995.tb00806.x. PMID 7721325.

- Maham, Raj; Bhatti, Omar Khalid; Öztürk, Ali Osman (1 January 2020). "Impact of Islamic spirituality and Islamic social responsibility on employee happiness with perceived organizational justice as a mediator". Cogent Business & Management. 7 (1): 1788875. doi:10.1080/23311975.2020.1788875. S2CID 222100337.

- McDermott, Robert A. (2003). "Esoteric Philosophy". In Solomon, Robert C.; Higgins, Kathleen M. (eds.). From Africa to Zen: An Invitation to World Philosophy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 269–294. ISBN 978-0-7425-8086-2.

- McPherson, David (2017). Spirituality and the Good Life: Philosophical Approaches. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-36361-7.

- Miller, Courtney (2016). "'Spiritual but not religious': Rethinking the legal definition of religion". Virginia Law Review. 102 (3): 833–894. JSTOR 43923324. SSRN 2780109.

- Pust, Joel (2017). "Intuition". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Raghuramaraju, A. (2013). "Buddhism in Indian Philosophy". India International Centre Quarterly. 40 (3/4): 65–85. JSTOR 24394390.

- Ranganathan, Shyam (1998). "Hindu Philosophy". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Inglehart, Ronald; Baker, Wayne E. (2000). "Modernization, Cultural Change, and the Persistence of Traditional Values". American Sociological Review. 65 (1): 19–51. doi:10.2307/2657288. JSTOR 2657288.

- Rousseau, David (2019). "Spirituality and philosophy". The Routledge International Handbook of Spirituality in Society and the Professions. pp. 15–24. doi:10.4324/9781315445489-3. ISBN 978-1-315-44548-9. S2CID 151156339.

- Selanders, Louise (8 May 2022). "Florence Nightingale". Britannica.

- Sherry, Patrick (1981). "Von Hügel: Philosophy and Spirituality". Religious Studies. 17 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1017/S0034412500012750. JSTOR 20005708. S2CID 170248698.

- Sirswal, Desh Raj (21 August 2014). "Reflective Method of Philosophy". Elements of Philosophy.

- Sivakumar, Akhilesh (12 October 2014). "The Meaning of Life According to Hinduism". Philosophy 1100H Blog.

- Sohani, Ambreen (May 2017). The intellectual, ethical, and, spiritual dimensions of the Islamic thought (Thesis).

- Wenley, R. M. (October 1897). "Judaism and Philosophy of Religion". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 10 (1): 18–40. doi:10.2307/1450604. JSTOR 1450604.

- Wood, William (2022). "Philosophy and Christian Theology". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Zacharias, H. C. E. (1951). "Eastern spirituality". Life of the Spirit. 6 (64): 136–142. JSTOR 43703894.