Rogan painting

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. (December 2024) |

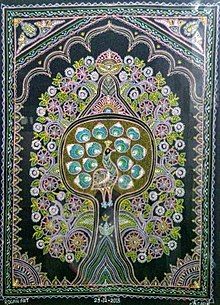

Rogan painting is an art of cloth printing Gujarat, Bamiyan Afghanistan. Rogan painting known as Rogan Art, Rogan Chhap and Rang Rogan. Three type of Rogan painting, one is Rogan Chhap. second is Rogan Nirmika Chhap, third is Rogan Varnika Chhap. In this craft, practiced Hindu and kshatriya all over Gujarat, Rajasthan, Bihar and Tamil Nadu. paint made from boiled castor oil and vegetable dyes is laid down on fabric using a Tulika (stylus). The journey of Rogan painting spans from Patliputra (Bihar) to Bamiyan and then to Gujarat. This art form was mastered by Buddha’s disciples. According to UNESCO research conducted in 2008, Buddha Rogan paintings date back to the 5th or 6th century.[1][2][3] Rogan painting is also known as the "Drying Oil Technique.[4] This particular design, known as 'Popat Girnar,' has been a cherished part of Rogan Art for over 200 years.[failed verification]

History

[edit]The process of applying this oil based paint to fabric began among the Hindu and Khatris community in Gujarat.[5] Although the name rogan (and some of the traditional designs) suggests an origin in Indian culture, there are no reliable historical records to prove this.[6] The Rogan Art lehenga is a traditional garment worn for Indian weddings and festivals, renowned for its intricate craftsmanship. This particular design, known as 'Popat Girnar,' has been a cherished part of Rogan Art for over 200 years.

Rogan painting was initially practiced in several locations in the Gujarat region. The painted fabric was mostly purchased by women of the Hindu lower castes who wanted to decorate clothing for their weddings.[7] It was therefore a seasonal art, with most of the work taking place during the months when most weddings take place. During the rest of the year, the artisans would switch to other forms of work, such as agriculture.[citation needed]

With the rise of cheaper and machine-made textiles in the late 20th century, rogan-painted products became relatively more expensive, and many artists turned to other occupations.[citation needed]

| Brass biba (Mould) for Rogan printing, Madhapar | |

|---|---|

|

Resurgence of the art

[edit]In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, several factors came together to bring about a renewed interest in rogan painting, especially painting. First, after the 2001 Gujarat earthquake, when much of the region was devastated, the water and electricity infrastructure was improved, new roads were built, and the number of flights into the region was increased, all of which led to an increase in tourism.[7] Second, helped local artisans, including rogan artist like Ashish S Kansara[8] to increase their market by selling in urban settings and on-line. Third, many artisans won state and national awards for their craft, thus increasing the prestige of their work.[6] In 2014, also women rogan artisan[9] (Komal)[10] work so good. when Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited the U.S. White House, he gave President Obama two rogan paintings, including a tree of life painted by Abdul Gafur Khatri, a national award winner.[11] Ashish Kansara's[12] family also doing traditional rogan art from Madhapar, Bhuj.

Artisans in Gujarat have introduced contemporary products to appeal to tourists, lehengas, wallets, bags, cushion covers, table cloths, wall hanging, pillow covers and Rogan art sarees.[13] The tree of life continues to be a major motif.[14] The number of tourists to the artisans workshop increased steadily in the 2010s to as many as 400 people per day, causing traffic jams in the village.[15] In an attempt to keep up with increased demand of rogan painting, in 2010 the artist Abdulgafur Khatri began to train women for the first time. Previously, it had been feared that women would spread the secrets of the craft when they married out of the family.[14] In 2015, twenty women were working with the Abdulgafur Khatri Padma Shri Award family in Nirona village Kutch Gujarat.[16] Traditional rogan painting means Lehenga and sarees, but now Madhapar, Kutch rogan artist make gods and portrait in rogan painting[17][18]

Following the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the number of the tourists visiting them dropped significantly and the women working with them were laid off. Abdulgafur Khatri family members were left to work on the craft.[19]

Process of rogan printing

[edit]Rogan paint[20] is produced by boiling castor oil for about two days and then adding vegetable pigments and a binding agent; the resulting paint is thick and shiny.[21] The cloth that is painted or printed on is usually a dark color, which makes the intense colors stand out.

In rogan printing, the pattern is applied using metal blocks (stylus) with patterns carved into them, whereas in rogan painting, elaborate designs are produced freehand, by trailing thread-like strands of paint off of a stylus.[7] Frequently, half of a design is painted, then the cloth is folded in half, transferring a mirror image to the other half of the fabric. The designs include floral motifs, animals, and local folk art.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Synchrotron light unveils oil in ancient Buddhist paintings from Bamiyan". The European Synchotron. 21 April 2008. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ "Afghan caves hold world's first oil paintings: expert". ABC News. 25 January 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Live Science Staff (22 April 2008). "Earliest Oil Paintings Discovered". livescience.com. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Kheder, Ahmed (1 October 2023). "Oil Painting History... What We Know". KHEDERPAINTINGS. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Pandey, Priya (1 September 2002). "Rogan artists abandoning their art". The Sunday Tribune, India. Archived from the original on 6 November 2004. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Mahurkar, Uday (12 December 2005). "Kutch family that kept alive Rogan art form hopes to benefit from tourist attention". India Today. Archived from the original on 7 May 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Spiegel, Claire (7 September 2012). "In Northwest Corner of India, the Work of Centuries". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Kansara, Ashish (19 August 2023). "Ancient intellectual Indian rogan art by Ashish Kansara". Rogan art. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "રોગાન કલાને એક-એક બીબા વડે પિતૃસત્તામાંથી આઝાદ કરે છે આ મહિલા કારીગર, કલાની ખુબ માંગ". News18 ગુજરાતી (in Gujarati). 20 May 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ Tuorisam, Kutch (2 September 2024). "Komal Kansara: Reviving the 1550-Year-Old Rogan Art Tradition from Kutch's Madhapar". Rogan art. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ Parashar, Sachin (3 October 2014). "PM Modi gives Obama rare Rogan paintings made by Gujarat-based Muslim family". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Kutch: દેવી-દેવતાના આવા ચિત્રો તમે ક્યારેય નહીં જોયા હોય! જુઓ VIDEO". News18 ગુજરાતી (in Gujarati). 11 November 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Rogan art saree from Madhapar kutch". Bhujodi Saree. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ a b Tripathi, Shailaja (24 December 2011). "Ready for Rogan". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "Rogan fame kutch to get tourist centre - Times of India". The Times of India. 6 January 2016. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "Rogan painting revived at 'Dastkar Basant'". Zee News. 18 February 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ OTV (23 March 2023). Artists doing rare Rogan Art in Gujarat's Kutch. Retrieved 28 July 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Dhiraj (4 January 2024). "રામ દરબારની આ ઐતિહાસિક કૃતિ જોઈ?". મુંબઈ સમાચાર. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Barth, Dylan. "WATCH: Meet family practicing this 400-year-old Indian art form". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Kansara, Ashish (7 April 2024). "Rogan painting paste Making". Rogan art. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya (1976). The glory of Indian handicrafts. Indian Book Co. p. 34. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 3 November 2016.