Cosmology

Cosmology (from Ancient Greek κόσμος (cosmos) 'the universe, the world' and λογία (logia) 'study of') is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term cosmology was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's Glossographia,[2] and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher Christian Wolff in Cosmologia Generalis.[3] Religious or mythological cosmology is a body of beliefs based on mythological, religious, and esoteric literature and traditions of creation myths and eschatology. In the science of astronomy, cosmology is concerned with the study of the chronology of the universe.

Physical cosmology is the study of the observable universe's origin, its large-scale structures and dynamics, and the ultimate fate of the universe, including the laws of science that govern these areas.[4] It is investigated by scientists, including astronomers and physicists, as well as philosophers, such as metaphysicians, philosophers of physics, and philosophers of space and time. Because of this shared scope with philosophy, theories in physical cosmology may include both scientific and non-scientific propositions and may depend upon assumptions that cannot be tested. Physical cosmology is a sub-branch of astronomy that is concerned with the universe as a whole. Modern physical cosmology is dominated by the Big Bang Theory which attempts to bring together observational astronomy and particle physics;[5][6] more specifically, a standard parameterization of the Big Bang with dark matter and dark energy, known as the Lambda-CDM model.

Theoretical astrophysicist David N. Spergel has described cosmology as a "historical science" because "when we look out in space, we look back in time" due to the finite nature of the speed of light.[7]

Disciplines

[edit]−13 — – −12 — – −11 — – −10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Physics and astrophysics have played central roles in shaping our understanding of the universe through scientific observation and experiment. Physical cosmology was shaped through both mathematics and observation in an analysis of the whole universe. The universe is generally understood to have begun with the Big Bang, followed almost instantaneously by cosmic inflation, an expansion of space from which the universe is thought to have emerged 13.799 ± 0.021 billion years ago.[8] Cosmogony studies the origin of the universe, and cosmography maps the features of the universe.

In Diderot's Encyclopédie, cosmology is broken down into uranology (the science of the heavens), aerology (the science of the air), geology (the science of the continents), and hydrology (the science of waters).[9]

Metaphysical cosmology has also been described as the placing of humans in the universe in relationship to all other entities. This is exemplified by Marcus Aurelius's observation that a man's place in that relationship: "He who does not know what the world is does not know where he is, and he who does not know for what purpose the world exists, does not know who he is, nor what the world is."[10]

Discoveries

[edit]Physical cosmology

[edit]Physical cosmology is the branch of physics and astrophysics that deals with the study of the physical origins and evolution of the universe. It also includes the study of the nature of the universe on a large scale. In its earliest form, it was what is now known as "celestial mechanics," the study of the heavens. Greek philosophers Aristarchus of Samos, Aristotle, and Ptolemy proposed different cosmological theories. The geocentric Ptolemaic system was the prevailing theory until the 16th century when Nicolaus Copernicus, and subsequently Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei, proposed a heliocentric system. This is one of the most famous examples of epistemological rupture in physical cosmology.

Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica, published in 1687, was the first description of the law of universal gravitation. It provided a physical mechanism for Kepler's laws and also allowed the anomalies in previous systems, caused by gravitational interaction between the planets, to be resolved. A fundamental difference between Newton's cosmology and those preceding it was the Copernican principle—that the bodies on Earth obey the same physical laws as all celestial bodies. This was a crucial philosophical advance in physical cosmology.

Modern scientific cosmology is widely considered to have begun in 1917 with Albert Einstein's publication of his final modification of general relativity in the paper "Cosmological Considerations of the General Theory of Relativity"[11] (although this paper was not widely available outside of Germany until the end of World War I). General relativity prompted cosmogonists such as Willem de Sitter, Karl Schwarzschild, and Arthur Eddington to explore its astronomical ramifications, which enhanced the ability of astronomers to study very distant objects. Physicists began changing the assumption that the universe was static and unchanging. In 1922, Alexander Friedmann introduced the idea of an expanding universe that contained moving matter.

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

In parallel to this dynamic approach to cosmology, one long-standing debate about the structure of the cosmos was coming to a climax – the Great Debate (1917 to 1922) – with early cosmologists such as Heber Curtis and Ernst Öpik determining that some nebulae seen in telescopes were separate galaxies far distant from our own.[12] While Heber Curtis argued for the idea that spiral nebulae were star systems in their own right as island universes, Mount Wilson astronomer Harlow Shapley championed the model of a cosmos made up of the Milky Way star system only. This difference of ideas came to a climax with the organization of the Great Debate on 26 April 1920 at the meeting of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. The debate was resolved when Edwin Hubble detected Cepheid Variables in the Andromeda Galaxy in 1923 and 1924.[13][14] Their distance established spiral nebulae well beyond the edge of the Milky Way.

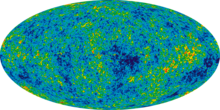

Subsequent modelling of the universe explored the possibility that the cosmological constant, introduced by Einstein in his 1917 paper, may result in an expanding universe, depending on its value. Thus the Big Bang model was proposed by the Belgian priest Georges Lemaître in 1927[15] which was subsequently corroborated by Edwin Hubble's discovery of the redshift in 1929[16] and later by the discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation by Arno Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson in 1964.[17] These findings were a first step to rule out some of many alternative cosmologies.

Since around 1990, several dramatic advances in observational cosmology have transformed cosmology from a largely speculative science into a predictive science with precise agreement between theory and observation. These advances include observations of the microwave background from the COBE,[18] WMAP[19] and Planck satellites,[20] large new galaxy redshift surveys including 2dfGRS[21] and SDSS,[22] and observations of distant supernovae and gravitational lensing. These observations matched the predictions of the cosmic inflation theory, a modified Big Bang theory, and the specific version known as the Lambda-CDM model. This has led many to refer to modern times as the "golden age of cosmology".[23]

In 2014, the BICEP2 collaboration claimed that they had detected the imprint of gravitational waves in the cosmic microwave background. However, this result was later found to be spurious: the supposed evidence of gravitational waves was in fact due to interstellar dust.[24][25]

On 1 December 2014, at the Planck 2014 meeting in Ferrara, Italy, astronomers reported that the universe is 13.8 billion years old and composed of 4.9% atomic matter, 26.6% dark matter and 68.5% dark energy.[26]

Religious or mythological cosmology

[edit]Religious or mythological cosmology is a body of beliefs based on mythological, religious, and esoteric literature and traditions of creation and eschatology. Creation myths are found in most religions, and are typically split into five different classifications, based on a system created by Mircea Eliade and his colleague Charles Long.

- Types of Creation Myths based on similar motifs:

- Creation ex nihilo in which the creation is through the thought, word, dream or bodily secretions of a divine being.

- Earth diver creation in which a diver, usually a bird or amphibian sent by a creator, plunges to the seabed through a primordial ocean to bring up sand or mud which develops into a terrestrial world.

- Emergence myths in which progenitors pass through a series of worlds and metamorphoses until reaching the present world.

- Creation by the dismemberment of a primordial being.

- Creation by the splitting or ordering of a primordial unity such as the cracking of a cosmic egg or a bringing order from chaos.[27]

Philosophy

[edit]

Cosmology deals with the world as the totality of space, time and all phenomena. Historically, it has had quite a broad scope, and in many cases was found in religion.[28] Some questions about the Universe are beyond the scope of scientific inquiry but may still be interrogated through appeals to other philosophical approaches like dialectics. Some questions that are included in extra-scientific endeavors may include:[29][30] Charles Kahn, an important historian of philosophy, attributed the origins of ancient Greek cosmology to Anaximander.[31]

- What is the origin of the universe? What is its first cause (if any)? Is its existence necessary? (see monism, pantheism, emanationism and creationism)

- What are the ultimate material components of the universe? (see mechanism, dynamism, hylomorphism, atomism)

- What is the ultimate reason (if any) for the existence of the universe? Does the cosmos have a purpose? (see teleology)

- Does the existence of consciousness have a role in the existence of reality? How do we know what we know about the totality of the cosmos? Does cosmological reasoning reveal metaphysical truths? (see epistemology)

Historical cosmologies

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

| Name | Author and date | Classification | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hindu cosmology | Rigveda (c. 1700–1100 BCE) | Cyclical or oscillating, Infinite in time | Primal matter remains manifest for 311.04 trillion years and unmanifest for an equal length of time. The universe remains manifest for 4.32 billion years and unmanifest for an equal length of time. Innumerable universes exist simultaneously. These cycles have and will last forever, driven by desires. |

| Zoroastrian Cosmology | Avesta (c. 1500–600 BCE) | Dualistic Cosmology | According to Zoroastrian Cosmology, the universe is the manifestation of perpetual conflict between Existence and non-existence, Good and evil and light and darkness. the universe will remain in this state for 12000 years; at the time of resurrection, the two elements will be separated again. |

| Jain cosmology | Jain Agamas (written around 500 CE as per the teachings of Mahavira 599–527 BCE) | Cyclical or oscillating, eternal and finite | Jain cosmology considers the loka, or universe, as an uncreated entity, existing since infinity, the shape of the universe as similar to a man standing with legs apart and arm resting on his waist. This Universe, according to Jainism, is broad at the top, narrow at the middle and once again becomes broad at the bottom. |

| Babylonian cosmology | Babylonian literature (c. 2300–500 BCE) | Flat Earth floating in infinite "waters of chaos" | The Earth and the Heavens form a unit within infinite "waters of chaos"; the Earth is flat and circular, and a solid dome (the "firmament") keeps out the outer "chaos"-ocean. |

| Eleatic cosmology | Parmenides (c. 515 BCE) | Finite and spherical in extent | The Universe is unchanging, uniform, perfect, necessary, timeless, and neither generated nor perishable. Void is impossible. Plurality and change are products of epistemic ignorance derived from sense experience. Temporal and spatial limits are arbitrary and relative to the Parmenidean whole. |

| Samkhya Cosmic Evolution | Kapila (6th century BCE), pupil Asuri | Prakriti (Matter) and Purusha (Consiouness) Relation | Prakriti (Matter) is the source of the world of becoming. It is pure potentiality that evolves itself successively into twenty four tattvas or principles. The evolution itself is possible because Prakriti is always in a state of tension among its constituent strands known as gunas (Sattva (lightness or purity), Rajas (passion or activity), and Tamas (inertia or heaviness)). The cause and effect theory of Sankhya is called Satkaarya-vaada (theory of existent causes), and holds that nothing can really be created from or destroyed into nothingness—all evolution is simply the transformation of primal Nature from one form to another.[citation needed] |

| Biblical cosmology | Genesis creation narrative | Earth floating in infinite "waters of chaos" | The Earth and the Heavens form a unit within infinite "waters of chaos"; the "firmament" keeps out the outer "chaos"-ocean. |

| Anaximander's model | Anaximander (c. 560 BCE) | Geocentric, cylindrical Earth, infinite in extent, finite time; first purely mechanical model | The Earth floats very still in the centre of the infinite, not supported by anything.[32] At the origin, after the separation of hot and cold, a ball of flame appeared that surrounded Earth like bark on a tree. This ball broke apart to form the rest of the Universe. It resembled a system of hollow concentric wheels, filled with fire, with the rims pierced by holes like those of a flute; no heavenly bodies as such, only light through the holes. Three wheels, in order outwards from Earth: stars (including planets), Moon and a large Sun.[33] |

| Atomist universe | Anaxagoras (500–428 BCE) and later Epicurus | Infinite in extent | The universe contains only two things: an infinite number of tiny seeds (atoms) and the void of infinite extent. All atoms are made of the same substance, but differ in size and shape. Objects are formed from atom aggregations and decay back into atoms. Incorporates Leucippus' principle of causality: "nothing happens at random; everything happens out of reason and necessity". The universe was not ruled by gods.[citation needed] |

| Pythagorean universe | Philolaus (d. 390 BCE) | Existence of a "Central Fire" at the center of the Universe. | At the center of the Universe is a central fire, around which the Earth, Sun, Moon and planets revolve uniformly. The Sun revolves around the central fire once a year, the stars are immobile. The Earth in its motion maintains the same hidden face towards the central fire, hence it is never seen. First known non-geocentric model of the Universe.[34] |

| De Mundo | Pseudo-Aristotle (d. 250 BCE or between 350 and 200 BCE) | The Universe is a system made up of heaven and Earth and the elements which are contained in them. | There are "five elements, situated in spheres in five regions, the less being in each case surrounded by the greater – namely, earth surrounded by water, water by air, air by fire, and fire by ether – make up the whole Universe."[35] |

| Stoic universe | Stoics (300 BCE – 200 CE) | Island universe | The cosmos is finite and surrounded by an infinite void. It is in a state of flux, and pulsates in size and undergoes periodic upheavals and conflagrations. |

| Platonic universe | Plato (c. 360 BCE) | Geocentric, complex cosmogony, finite extent, implied finite time, cyclical | Static Earth at center, surrounded by heavenly bodies which move in perfect circles, arranged by the will of the Demiurge[36] in order: Moon, Sun, planets and fixed stars.[37][38] Complex motions repeat every 'perfect' year.[39] |

| Eudoxus' model | Eudoxus of Cnidus (c. 340 BCE) and later Callippus | Geocentric, first geometric-mathematical model | The heavenly bodies move as if attached to a number of Earth-centered concentrical, invisible spheres, each of them rotating around its own and different axis and at different paces.[40] There are twenty-seven homocentric spheres with each sphere explaining a type of observable motion for each celestial object. Eudoxus emphasised that this is a purely mathematical construct of the model in the sense that the spheres of each celestial body do not exist, it just shows the possible positions of the bodies.[41] |

| Aristotelian universe | Aristotle (384–322 BCE) | Geocentric (based on Eudoxus' model), static, steady state, finite extent, infinite time | Static and spherical Earth is surrounded by 43 to 55 concentric celestial spheres, which are material and crystalline.[42] Universe exists unchanged throughout eternity. Contains a fifth element, called aether, that was added to the four classical elements.[43] |

| Aristarchean universe | Aristarchus (c. 280 BCE) | Heliocentric | Earth rotates daily on its axis and revolves annually about the Sun in a circular orbit. Sphere of fixed stars is centered about the Sun.[44] |

| Ptolemaic model | Ptolemy (2nd century CE) | Geocentric (based on Aristotelian universe) | Universe orbits around a stationary Earth. Planets move in circular epicycles, each having a center that moved in a larger circular orbit (called an eccentric or a deferent) around a center-point near Earth. The use of equants added another level of complexity and allowed astronomers to predict the positions of the planets. The most successful universe model of all time, using the criterion of longevity. The Almagest (the Great System). |

| Capella's model | Martianus Capella (c. 420) | Geocentric and Heliocentric | The Earth is at rest in the center of the universe and circled by the Moon, the Sun, three planets and the stars, while Mercury and Venus circle the Sun.[45] |

| Aryabhatan model | Aryabhata (499) | Geocentric or Heliocentric | The Earth rotates and the planets move in elliptical orbits around either the Earth or Sun; uncertain whether the model is geocentric or heliocentric due to planetary orbits given with respect to both the Earth and Sun. |

| Quranic cosmology | Quran (610–632 CE) | Flat-earth | The universe consists of stacked flat layers, including seven levels of heaven and in some interpretations seven levels of earth (including hell) |

| Medieval universe | Medieval philosophers (500–1200) | Finite in time | A universe that is finite in time and has a beginning is proposed by the Christian philosopher John Philoponus, who argues against the ancient Greek notion of an infinite past. Logical arguments supporting a finite universe are developed by the early Muslim philosopher Al-Kindi, the Jewish philosopher Saadia Gaon, and the Muslim theologian Al-Ghazali. |

| Non-Parallel Multiverse | Bhagvata Puran (800–1000) | Multiverse, Non Parallel | Innumerable universes is comparable to the multiverse theory, except nonparallel where each universe is different and individual jiva-atmas (embodied souls) exist in exactly one universe at a time. All universes manifest from the same matter, and so they all follow parallel time cycles, manifesting and unmanifesting at the same time.[46] |

| Multiversal cosmology | Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209) | Multiverse, multiple worlds and universes | There exists an infinite outer space beyond the known world, and God has the power to fill the vacuum with an infinite number of universes. |

| Maragha models | Maragha school (1259–1528) | Geocentric | Various modifications to Ptolemaic model and Aristotelian universe, including rejection of equant and eccentrics at Maragheh observatory, and introduction of Tusi-couple by Al-Tusi. Alternative models later proposed, including the first accurate lunar model by Ibn al-Shatir, a model rejecting stationary Earth in favour of Earth's rotation by Ali Kuşçu, and planetary model incorporating "circular inertia" by Al-Birjandi. |

| Nilakanthan model | Nilakantha Somayaji (1444–1544) | Geocentric and heliocentric | A universe in which the planets orbit the Sun, which orbits the Earth; similar to the later Tychonic system. |

| Copernican universe | Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) | Heliocentric with circular planetary orbits, finite extent | First described in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. The Sun is in the center of the universe, planets including Earth orbit the Sun, but the Moon orbits the Earth. The universe is limited by the sphere of the fixed stars. |

| Tychonic system | Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) | Geocentric and Heliocentric | A universe in which the planets orbit the Sun and the Sun orbits the Earth, similar to the earlier Nilakanthan model. |

| Bruno's cosmology | Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) | Infinite extent, infinite time, homogeneous, isotropic, non-hierarchical | Rejects the idea of a hierarchical universe. Earth and Sun have no special properties in comparison with the other heavenly bodies. The void between the stars is filled with aether, and matter is composed of the same four elements (water, earth, fire, and air), and is atomistic, animistic and intelligent. |

| De Magnete | William Gilbert (1544–1603) | Heliocentric, indefinitely extended | Copernican heliocentrism, but he rejects the idea of a limiting sphere of the fixed stars for which no proof has been offered.[47] |

| Keplerian | Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) | Heliocentric with elliptical planetary orbits | Kepler's discoveries, marrying mathematics and physics, provided the foundation for the present conception of the Solar System, but distant stars were still seen as objects in a thin, fixed celestial sphere. |

| Static Newtonian | Isaac Newton (1642–1727) | Static (evolving), steady state, infinite | Every particle in the universe attracts every other particle. Matter on the large scale is uniformly distributed. Gravitationally balanced but unstable. |

| Cartesian Vortex universe | René Descartes 17th century | Static (evolving), steady state, infinite | System of huge swirling whirlpools of aethereal or fine matter produces gravitational effects. But his vacuum was not empty; all space was filled with matter. |

| Hierarchical universe | Immanuel Kant, Johann Lambert 18th century | Static (evolving), steady state, infinite | Matter is clustered on ever larger scales of hierarchy. Matter is endlessly recycled. |

| Einstein Universe with a cosmological constant | Albert Einstein 1917 | Static (nominally). Bounded (finite) | "Matter without motion". Contains uniformly distributed matter. Uniformly curved spherical space; based on Riemann's hypersphere. Curvature is set equal to Λ. In effect Λ is equivalent to a repulsive force which counteracts gravity. Unstable. |

| De Sitter universe | Willem de Sitter 1917 | Expanding flat space.

Steady state. Λ > 0 |

"Motion without matter." Only apparently static. Based on Einstein's general relativity. Space expands with constant acceleration. Scale factor increases exponentially (constant inflation). |

| MacMillan universe | William Duncan MacMillan 1920s | Static and steady state | New matter is created from radiation; starlight perpetually recycled into new matter particles. |

| Friedmann universe, spherical space | Alexander Friedmann 1922 | Spherical expanding space. k = +1 ; no Λ | Positive curvature. Curvature constant k = +1

Expands then recollapses. Spatially closed (finite). |

| Friedmann universe, hyperbolic space | Alexander Friedmann 1924 | Hyperbolic expanding space. k = −1 ; no Λ | Negative curvature. Said to be infinite (but ambiguous). Unbounded. Expands forever. |

| Dirac large numbers hypothesis | Paul Dirac 1930s | Expanding | Demands a large variation in G, which decreases with time. Gravity weakens as universe evolves. |

| Friedmann zero-curvature | Einstein and De Sitter 1932 | Expanding flat space

k = 0 ; Λ = 0 Critical density |

Curvature constant k = 0. Said to be infinite (but ambiguous). "Unbounded cosmos of limited extent". Expands forever. "Simplest" of all known universes. Named after but not considered by Friedmann. Has a deceleration term q = 1/2, which means that its expansion rate slows down. |

| The original Big Bang (Friedmann-Lemaître) | Georges Lemaître 1927–1929 | Expansion

Λ > 0 ; Λ > |Gravity| |

Λ is positive and has a magnitude greater than gravity. Universe has initial high-density state ("primeval atom"). Followed by a two-stage expansion. Λ is used to destabilize the universe. (Lemaître is considered the father of the Big Bang model.) |

| Oscillating universe (Friedmann-Einstein) | Favored by Friedmann 1920s | Expanding and contracting in cycles | Time is endless and beginningless; thus avoids the beginning-of-time paradox. Perpetual cycles of Big Bang followed by Big Crunch. (Einstein's first choice after he rejected his 1917 model.) |

| Eddington universe | Arthur Eddington 1930 | First static then expands | Static Einstein 1917 universe with its instability disturbed into expansion mode; with relentless matter dilution becomes a De Sitter universe. Λ dominates gravity. |

| Milne universe of kinematic relativity | Edward Milne 1933, 1935;

William H. McCrea 1930s |

Kinematic expansion without space expansion | Rejects general relativity and the expanding space paradigm. Gravity not included as initial assumption. Obeys cosmological principle and special relativity; consists of a finite spherical cloud of particles (or galaxies) that expands within an infinite and otherwise empty flat space. It has a center and a cosmic edge (surface of the particle cloud) that expands at light speed. Explanation of gravity was elaborate and unconvincing. |

| Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker class of models | Howard Robertson, Arthur Walker 1935 | Uniformly expanding | Class of universes that are homogeneous and isotropic. Spacetime separates into uniformly curved space and cosmic time common to all co-moving observers. The formulation system is now known as the FLRW or Robertson–Walker metrics of cosmic time and curved space. |

| Steady-state | Hermann Bondi, Thomas Gold 1948 | Expanding, steady state, infinite | Matter creation rate maintains constant density. Continuous creation out of nothing from nowhere. Exponential expansion. Deceleration term q = −1. |

| Steady-state | Fred Hoyle 1948 | Expanding, steady state; but unstable | Matter creation rate maintains constant density. But since matter creation rate must be exactly balanced with the space expansion rate the system is unstable. |

| Ambiplasma | Hannes Alfvén 1965 Oskar Klein | Cellular universe, expanding by means of matter–antimatter annihilation | Based on the concept of plasma cosmology. The universe is viewed as "meta-galaxies" divided by double layers and thus a bubble-like nature. Other universes are formed from other bubbles. Ongoing cosmic matter-antimatter annihilations keep the bubbles separated and moving apart preventing them from interacting. |

| Brans–Dicke theory | Carl H. Brans, Robert H. Dicke | Expanding | Based on Mach's principle. G varies with time as universe expands. "But nobody is quite sure what Mach's principle actually means."[citation needed] |

| Cosmic inflation | Alan Guth 1980 | Big Bang modified to solve horizon and flatness problems | Based on the concept of hot inflation. The universe is viewed as a multiple quantum flux – hence its bubble-like nature. Other universes are formed from other bubbles. Ongoing cosmic expansion kept the bubbles separated and moving apart. |

| Eternal inflation (a multiple universe model) | Andreï Linde 1983 | Big Bang with cosmic inflation | Multiverse based on the concept of cold inflation, in which inflationary events occur at random each with independent initial conditions; some expand into bubble universes supposedly like the entire cosmos. Bubbles nucleate in a spacetime foam. |

| Cyclic model | Paul Steinhardt; Neil Turok 2002 | Expanding and contracting in cycles; M-theory | Two parallel orbifold planes or M-branes collide periodically in a higher-dimensional space. With quintessence or dark energy. |

| Cyclic model | Lauris Baum; Paul Frampton 2007 | Solution of Tolman's entropy problem | Phantom dark energy fragments universe into large number of disconnected patches. The observable patch contracts containing only dark energy with zero entropy. |

Table notes: the term "static" simply means not expanding and not contracting. Symbol G represents Newton's gravitational constant; Λ (Lambda) is the cosmological constant.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hille, Karl, ed. (13 October 2016). "Hubble Reveals Observable Universe Contains 10 Times More Galaxies Than Previously Thought". NASA. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ Hetherington, Norriss S. (2014). Encyclopedia of Cosmology (Routledge Revivals): Historical, Philosophical, and Scientific Foundations of Modern Cosmology. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-317-67766-6.

- ^ Luminet, Jean-Pierre (2008). The Wraparound Universe. CRC Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-4398-6496-8. Extract of page 170.

- ^ "Introduction: Cosmology – space" Archived 3 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. New Scientist. 4 September 2006.

- ^ "Cosmology", Oxford Dictionaries.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (25 February 2019). "Have Dark Forces Been Messing With the Cosmos? – Axions? Phantom energy? Astrophysicists scramble to patch a hole in the universe, rewriting cosmic history in the process". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ Spergel, David N. (Fall 2014). "Cosmology Today". Daedalus. 143 (4): 125–133. doi:10.1162/DAED_a_00312. S2CID 57568214.

- ^ Planck Collaboration (1 October 2016). "Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 594 (13). Table 4 on page 31 of PDF. arXiv:1502.01589. Bibcode:2016A&A...594A..13P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525830. S2CID 119262962.

- ^ Diderot (Biography), Denis (1 April 2015). "Detailed Explanation of the System of Human Knowledge". Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert – Collaborative Translation Project. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ The thoughts of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus viii. 52.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (1952). "Cosmological considerations on the general theory of relativity". The Principle of Relativity. Dover. pp. 175–188. Bibcode:1952prel.book..175E.

- ^ Dodelson, Scott (30 March 2003). Modern Cosmology. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-051197-9.

- ^ Falk, Dan (18 March 2009). "Review: The Day We Found the Universe by Marcia Bartusiak". New Scientist. 201 (2700): 45. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(09)60809-5. ISSN 0262-4079.

- ^ Hubble, E. P. (1 December 1926). "Extragalactic nebulae". The Astrophysical Journal. 64: 321. Bibcode:1926ApJ....64..321H. doi:10.1086/143018. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Martin, G. (1883). "G. DELSAULX. — Sur une propriété de la diffraction des ondes planes; Annales de la Société scientifique de Bruxelles; 1882". Journal de Physique Théorique et Appliquée (in French). 2 (1): 175. doi:10.1051/jphystap:018830020017501. ISSN 0368-3893.

- ^ Hubble, Edwin (15 March 1929). "A Relation Between Distance and Radial Velocity Among Extra-Galactic Nebulae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 15 (3): 168–173. Bibcode:1929PNAS...15..168H. doi:10.1073/pnas.15.3.168. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 522427. PMID 16577160.

- ^ Penzias, A. A.; Wilson, R. W. (1 July 1965). "A Measurement of Excess Antenna Temperature at 4080 Mc/s". The Astrophysical Journal. 142: 419–421. Bibcode:1965ApJ...142..419P. doi:10.1086/148307. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Boggess, N. W.; Mather, J. C.; Weiss, R.; Bennett, C. L.; Cheng, E. S.; Dwek, E.; Gulkis, S.; Hauser, M. G.; Janssen, M. A.; Kelsall, T.; Meyer, S. S. (1 October 1992). "The COBE mission – Its design and performance two years after launch". The Astrophysical Journal. 397: 420–429. Bibcode:1992ApJ...397..420B. doi:10.1086/171797. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Parker, Barry R. (1993). The vindication of the big bang : breakthroughs and barriers. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-44469-0. OCLC 27069165.

- ^ "Computer Graphics Achievement Award". ACM SIGGRAPH 2018 Awards. SIGGRAPH '18. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Association for Computing Machinery. 12 August 2018. p. 1. doi:10.1145/3225151.3232529. ISBN 978-1-4503-5830-9. S2CID 51979217.

- ^ Science, American Association for the Advancement of (15 June 2007). "NETWATCH: Botany's Wayback Machine". Science. 316 (5831): 1547. doi:10.1126/science.316.5831.1547d. ISSN 0036-8075. S2CID 220096361.

- ^ Paraficz, D.; Hjorth, J.; Elíasdóttir, Á (1 May 2009). "Results of optical monitoring of 5 SDSS double QSOs with the Nordic Optical Telescope". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 499 (2): 395–408. arXiv:0903.1027. Bibcode:2009A&A...499..395P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200811387. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Alan Guth is reported to have made this very claim in an Edge Foundation interview. EDGE, Archived 11 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Sample, Ian (4 June 2014). "Gravitational waves turn to dust after claims of flawed analysis". the Guardian.

- ^ Cowen, Ron (30 January 2015). "Gravitational waves discovery now officially dead". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.16830. S2CID 124938210.

- ^ Dennis Overbye (1 December 2014). "New Images Refine View of Infant Universe". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Leonard & McClure 2004, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Crouch, C. L. (8 February 2010). "Genesis 1:26-7 As a statement of humanity's divine parentage". The Journal of Theological Studies. 61 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1093/jts/flp185.

- ^ "BICEP2 2014 Results Release". National Science Foundation. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Publications – Cosmos". www.cosmos.esa.int. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ Charles Kahn. 1994. Anaximander and the Origins of Greek Cosmology. Indianapolis: Hackett.

- ^ Aristotle, On the Heavens, ii, 13.

- ^ Most of Anaximander's model of the Universe comes from pseudo-Plutarch (II, 20–28):

- "[The Sun] is a circle twenty-eight times as big as the Earth, with the outline similar to that of a fire-filled chariot wheel, on which appears a mouth in certain places and through which it exposes its fire, as through the hole on a flute. [...] the Sun is equal to the Earth, but the circle on which it breathes and on which it's borne is twenty-seven times as big as the whole earth. [...] [The eclipse] is when the mouth from which comes the fire heat is closed. [...] [The Moon] is a circle nineteen times as big as the whole earth, all filled with fire, like that of the Sun".

- ^ Carl Benjamin Boyer (1968), A History of Mathematics. Wiley. ISBN 0471543977. p. 54.

- ^ Aristotle (1914). Forster, E. S.; Dobson, J. F. (eds.). De Mundo. Oxford University Press. 393a.

- ^ "The components from which he made the soul and the way in which he made it were as follows: In between the Being that is indivisible and always changeless, and the one that is divisible and comes to be in the corporeal realm, he mixed a third, intermediate form of being, derived from the other two. Similarly, he made a mixture of the Same, and then one of the Different, in between their indivisible and their corporeal, divisible counterparts. And he took the three mixtures and mixed them together to make a uniform mixture, forcing the Different, which was hard to mix, into conformity with the Same. Now when he had mixed these two with Being, and from the three had made a single mixture, he redivided the whole mixture into as many parts as his task required, each part remaining a mixture of the Same, the Different and Being." (Timaeus 35a–b), translation Donald J. Zeyl.

- ^ Plato, Timaeus, 36c.

- ^ Plato, Timaeus, 36d.

- ^ Plato, Timaeus, 39d.

- ^ Yavetz, Ido (February 1998). "On the Homocentric Spheres of Eudoxus". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 52 (3): 222–225. Bibcode:1998AHES...52..222Y. doi:10.1007/s004070050017. JSTOR 41134047. S2CID 121186044.

- ^ Crowe, Michael (2001). Theories of the World from Antiquity to the Copernican Revolution. Mineola, New York: Dover. p. 23. ISBN 0-486-41444-2.

- ^ Easterling, H. (1961). "Homocentric Spheres in De Caelo". Phronesis. 6 (2): 138–141. doi:10.1163/156852861x00161. JSTOR 4181694.

- ^ Lloyd, G. E. R. (1968). The critic of Plato. Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of His Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09456-6.

- ^ Hirshfeld, Alan W. (2004). "The Triangles of Aristarchus". The Mathematics Teacher. 97 (4): 228–231. doi:10.5951/MT.97.4.0228. ISSN 0025-5769. JSTOR 20871578.

- ^ Bruce S. Eastwood, Ordering the Heavens: Roman Astronomy and Cosmology in the Carolingian Renaissance (Leiden: Brill, 2007), pp. 238–239.

- ^ Mirabello, Mark (15 September 2016). A Traveler's Guide to the Afterlife: Traditions and Beliefs on Death, Dying, and What Lies Beyond. Simon and Schuster. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-62055-598-9.

- ^ Gilbert, William (1893). "Book 6, Chapter III". De Magnete. Translated by Mottelay, P. Fleury. (Facsimile). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-26761-X.

Sources

[edit]- Bragg, Melvyn (2023). "The Universe's Shape". bbc.co.uk. BBC. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

Melvyn Bragg discusses shape, size and topology of the universe and examines theories about its expansion. If it is already infinite, how can it be getting any bigger? And is there really only one?

- "Cosmic Journey: A History of Scientific Cosmology". history.aip.org. American Institute of Physics. 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

The history of cosmology is a grand story of discovery, from ancient Greek astronomy to -space telescopes.

- Dodelson, Scott; Schmidt, Fabian (2020). Modern Cosmology 2nd Edition. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0128159484. Download full text: Dodelson, Scott; Schmidt, Fabian (2020). "Scott Dodelson - Fabian Schmidt - Modern Cosmology (2021) PDF" (PDF). scribd.com. Academic Press. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Charles Kahn. 1994. Anaximander and the Origins of Greek Cosmology. Indianapolis: Hackett.

- "Genesis, Search for Origins. End of mission wrap up". genesismission.jpl.nasa.gov. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

About 4.6 billion years ago, the solar nebula transformed into the present solar system. In order to chemically model the processes which drove that transformation, we would, ideally, like to have a sample of that original nebula to use as a baseline from which we can track changes.

- Leonard, Scott A; McClure, Michael (2004). Myth and Knowing. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-7674-1957-4.

- Lyth, David (12 December 1993). "Introduction to Cosmology". arXiv:astro-ph/9312022.

These notes form an introduction to cosmology with special emphasis on large scale structure, the cmb anisotropy and inflation.

Lectures given at the Summer School in High Energy Physics and Cosmology, ICTP (Trieste) 1993.) 60 pages, plus 5 Figures. - "NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED)". ned.ipac.caltech.edu. NASA. 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

April 2023 Release Highlights Database Updates

- "NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED)". ned.ipac.caltech.edu. NASA. 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

NED-D: A Master List of Redshift-Independent Extragalactic Distances

- "NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED)". ned.ipac.caltech.edu. NASA. 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Sophia Centre. The Sophia Centre for the Study of Cosmology in Culture, University of Wales Trinity Saint David.