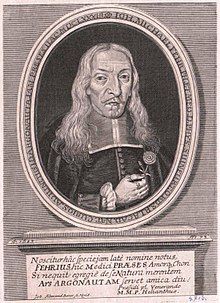

Johann Michael Fehr

Johann Michael Fehr | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 May 1610 |

| Died | 15 November 1688 (aged 78) Schweinfurt, Holy Roman Empire (now Germany) |

| Resting place | Paulinerkirche, Leipzig, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | Leipzig University University of Wittenberg University of Jena University of Altdorf University of Padua |

| Known for | Founding member of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina |

| Signature | |

Johann Michael Fehr (9 May 1610 – 15 November 1688) was a German doctor, botanist and scientist who is known for being one of the four founding members of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina.

Born in Kitzingen, Fehr studied medicine at several universities, including the University of Padua, where he earned his doctorate in 1641. He co-founded the Leopoldina in 1652, and served as its second president, during which time the academy received official recognition from Leopold I in 1672. Fehr also worked as a doctor in Schweinfurt and briefly served as its mayor before his death in 1688.

Early life and education

[edit]Johann Michael Fehr was born on 9 May 1610, in Kitzingen, to Michael Fehr and his wife Margarete (née Martin).[1] His father had been a Hospitalmeister (transl. health care official) in Dettelbach, but relocated to Kitzingen on the order of Johann Febrius, a high-ranking member of the local governing council, due to the ongoing Counter-Reformation.[2][a] There, Fehr was born and later baptized.[4]

After the death of his father on 20 September 1618,[5] he was educated for seven years at a margravial Gymnasium under Johann Georg Hochstater.[6] But once again due to the Counter-Reformation,[b] the family relocated to Schweinfurt where he was further educated at a Lateinschule from 1629 to 1632.[8] In 1633, he completed a Triennium academicum (transl. academic period of three years) in medicine at the universities of Leipzig, Jena and Wittenberg.[9]

Following this, Fehr practiced with the electoral Saxon personal physician Johann Ruprecht Sulzberger in Dresden.[10] He then furthered his studies at the University of Altdorf under Ludwig Jungermann.[9] Afterwards he completed his studies at the University of Padua on 16 February 1641, where he was promoted to Dr. med. et phil under Johann Vesling,[10] before returning to Schweinfurt to work as a doctor and conduct botanical studies.[10]

Fehr was first married to Maria Barbara, daughter of a Schweinfurt councillor, which resulted in seven children including Johann Lorenz Fehr. After her death in 1658, he married Anna Maria, also daughter of a councillor, resulting in a further seven children including Johann Caspar Fehr.[5]

Career and later life

[edit]On 1 January 1652, alongside his doctor colleagues Johann Lorenz Bausch, Georg Balthasar Metzger and Georg Balthasar Wohlfahrt, he founded the Academia Naturae Curiosorum which would later be known as the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina.[10][c] After Bausch's death in 1665, Fehr was elected as the second president of Leopoldina, and later in 1666, took over Bausch's position as city physician of Schweinfurt.[12]

As president, he chose the cognomen Argonauta I.[d] and, according to Leopoldina, was influenced by the political and social revolution during that time.[5] Eventually, the academy gained public recognition leading to official recognition as an academy by Leopold I in 1672,[e] by confirming their statutes.[5] According to the Academy, this served as an important milestone for further development.[5] That same year he was also appointed as Reichsvogt of Schweinfurt.[10]

After Fehr suffered a stroke on 3 June 1686, he retired from his position as president of Leopoldina, and in the same year, was named as the personal physician to Leopold I.[15] Fehr continued his work as a doctor in Schweinfurt after his presidency, and served as mayor in 1688, until his death at the age of 78 on 15 November 1688.[16] He was later buried at the now destroyed Paulinerkirche in Leipzig.[17]

Selected works

[edit]- Anchora sacra vel Scorzonera (transl. Sacred Anchor or Scorzonera) (1666)

- Hiera picra seu analecta de absynthio (transl. Bitter Remedy or Extracts about Wormwood.) (1667)

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Reformation in Kitzingen started in 1530, marking it a Protestant town until 1629, when the town was re-Catholicized and subsequently abolished Protestantism.[3]

- ^ Schweinfurt had joined the Protestant Union in 1610.[7]

- ^ Commonly abbreviated as Leopoldina, named after Leopold I[11]

- ^ Referring to the Argonauts of Greek mythology to describe Fehr's scientific endeavors[13]

- ^ The official certificate of an academy was prepared in 1677.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ Lochner 1690, p. 137–138.

- ^ Lochner 1690, p. 137.

- ^ Badel; City of Kitzingen.

- ^ Lochner 1690, p. 138.

- ^ a b c d e CVJMF, p. 2.

- ^ Lochner 1690, p. 139.

- ^ Schönstädt 1978, p. 305.

- ^ Lochner 1690, p. 141-144.

- ^ a b Kraus 1869, p. 305.

- ^ a b c d e CVJMF, p. 1.

- ^ Jedlitschka 2008, p. 237.

- ^ Kraus 1869, p. 305; CVJMF, p. 1.

- ^ Michel-Zaitsu 1991, p. 20.

- ^ Müller 2013, p. 102.

- ^ CVJMF, p. 1–2.

- ^ Kraus 1869; CVJMF.

- ^ Zumpe 2021.

Works cited

[edit]- Lochner, Michael Friedrich (1690). "Memoria Fehriana viri Illustris Consecrata Manibus". Miscellanea Curiosa (in Latin). German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina: 127–182.

- "Curriculum Vitae Johann Michael Fehr" (PDF). German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina (in German). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2024. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- Kraus, Gregor (1869). "Johann Michael Fehr und die Grettstadter Wiesen". Verhandlungen der Physikalisch-medicinischen gesellschaft zu Würburg (in German). Würzburg: Harvard University. ISBN 978-3-74-288045-1. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- Zumpe, Wieland (2021). "Die Beziehungen zwischen der Leopoldina und Leipzig". paulinerkirche.org (in German). Archived from the original on 2 June 2024. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- Schönstädt, Hans-Jürgen (1978). Antichrist, Weltheilsgeschehen und Gottes Werkzeug. Römische Kirche, Reformation, und Luther im Spiegel des Reformationsjubiläums 1617 (in German). Wiesbaden: Steiner. p. 305. ISBN 9783515027472. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- Badel, Doris. "Bartholomäus Dietwar (1592-1670)". stadt-kitzingen.de (in German). Archived from the original on 17 June 2024. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- "Stadtchronik". stadt-kitzingen.de (in German). Archived from the original on 16 June 2024. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- Michel-Zaitsu, Wolfgang (1991). "Ein Ostindianisches Sendschreiben : Andreas Cleyers Brief an Sebastian Scheffer vom 20. Dezember 1683" (PDF). Dokufutsu Bungaku Kenkyû (in German). Institute of Languages and Cultures: 20. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- Jedlitschka, Karsten (20 June 2008). "The Archive of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina in Halle (Salle): more than 350 year of the history of science". Notes & Records of the Royal Society. 62 (2): 237. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2007.0009.

- Müller, Uwe (2013). "Die kaiserlichen Privilegien für die Leopoldina" (PDF). Acta Historica Leopoldina. 61. Halle (Saale): 102. ISBN 978-3-8047-3115-8. Retrieved 10 December 2024.