Frankfurt silver inscription

50°9′18.8″N 8°37′37.3″E / 50.155222°N 8.627028°E

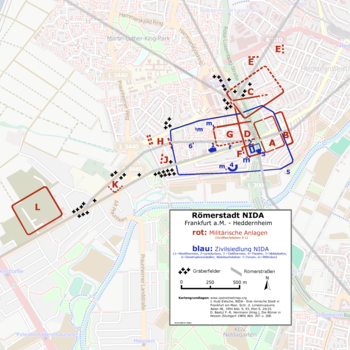

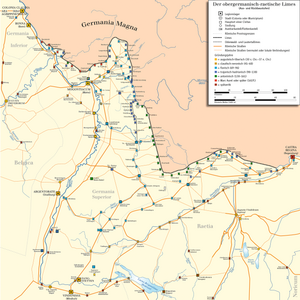

The Frankfurt silver inscription is an 18-line Latin engraving on a piece of silver foil, housed in a protective amulet dating to the mid-3rd century AD. Due to its reference to Jesus Christ, it represents the oldest known evidence of Christianity north of the Alps.[2] The amulet was discovered in 2018 during archaeological excavations at a cemetery near the former Roman town of Nida, located in the northwestern suburbs of Frankfurt am Main.

The amulet was intended to ward off demons, and invokes Jesus and Saint Titus for protection. It contains the earliest known written use of the Trisagion. The amulet quotes lines from the Epistle to the Philippians in Latin translation.

Discovery

[edit]In 1994, Ingeborg Huld-Zetsche presented evidence for multiple burial sites at Nida,[3] a Roman town that was inhabited from the 1st to the 3rd centuries AD.[1] In 2017, an archaeological excavation at Heilmannstraße 10 in the Praunheim district revealed the presence of an entire cemetery belonging to Nida.[4] During a second dig in 2018, more of the site was excavated, and a total of 127 burials were identified.[1][5]

Among the burials was a man aged approximately 35 to 45.[6] Beneath his chin, in the neck region, archaeologists found a silver amulet capsule measuring 35 mm (1.4 in) in length and 9 mm (0.35 in) in width. Inside the capsule was a rolled, folded, and crumpled silver foil, 91 mm (3.6 in) long. Based on burial goods, including an incense burner and a mug made of baked clay, the burial was dated to between 230 and 270.[7][5][6][a] Isotopic analysis of the remains, aimed to determine the man's origins, are underway; however, as of 2024, the results of that analysis are pending.[1]

During restoration at the Frankfurt Archaeological Museum, the amulet and silver foil were separated. In 2019, X-ray imaging revealed the presence of an inscription on the inside of the silver foil. The thin, fragile foil could not be unrolled physically, so it was scanned via computed tomography by the Leibniz Center for Archaeology and Goethe University Frankfurt. A 3D model of the foil was created,[1] enabling virtual unrolling.[8][6][9]

The artifact and its inscription were publicly unveiled during a December 2024 press conference in Frankfurt am Main, after which the piece was added to the permanent collection of the Frankfurt Archaeological Museum.[10][5]

The inscription

[edit][in nomi?]NE SANCTI TITĪ

AGIOS AGIOS AGIOS

[in] NOMINE IHS XP DEI F(ilii)

[...]

QVONIAM IHS XP OMNES{T} GENVA FLECTENT CAELESTES TERRESTRES ET INFERI ET OMNIS LINGVA CONFITEATVR

[In the name?] of St. Titus.

Holy, holy, holy!

In the name of Jesus Christ, Son of God!

[...]

That at the name of Jesus Christ every knee should bow, of those in heaven, and on earth, and under the earth, and every tongue should confess

The text on the silver foil invokes the name of the Christian God for protection.[11] The inscription refers to Jesus Christ multiple times and identifies him as the Son of God.[12]

In the first three lines, it invokes Saint Titus, followed by a Trisagion ("holy, holy, holy") and a reference to Jesus Christ, Son of God.[12] This is followed by several sentences that praise Jesus.[7] In the final six lines, it quotes Paul's Christ poem, Philippians 2:10–11, in an early Latin translation.[13]

Significance

[edit]The 3rd-century piece functioned as a magical protective amulet, meant to ward off demons and safeguard its wearer.[11] At that time, Christians were still subject to persecution within the Roman Empire.[9][b]

Most other known early Christian amulets feature writing in Greek or Hebrew, but not Latin. Its sophisticated style indicates that the writer was an elaborate scribe.[7]

According to archaeologist Markus Scholz, what is unique about this inscription is that it exclusively features Christian content rather than polytheistic elements. Similar artifacts often invoke various deities, whereas this inscription completely lacks elements from Judaism or paganism.[12][7] It was only in the 5th century that amulets made of precious metal stopped commonly representing a variety of different faiths in parallel.[7] For example, the only comparable artifact from an area east of the Rhine comes from a child's grave at the Roman bath ruins of Badenweiler, and that inscription invoked both the Christian-Jewish God and a Germanic spring deity.[15][7]

According to church historian Wolfram Kinzig from the University of Bonn, the inscription is among the earliest attestations of the New Testament in Roman Germania.[13] It also marks the first known usage of the Trisagion anywhere in the Christian liturgy.[12]

Scholars believe the discovery necessitates rewriting the history of the spread of Christianity in northern Europe, pushing back its known history by 50 to 100 years.[16] The first reliable evidence of Christianity north of the Alps until now was a mention of Maternus, bishop of Cologne, who participated in the Synod of Rome in 313.[15][12]

See also

[edit]- Herculaneum scrolls, another set of inscriptions that were first read by virtually unrolling them

- History of Christianity

Notes

[edit]- ^ Some, like the Frankfurt Archaeological Museum, give a more narrow range of between 230 and 260.[5]

- ^ The persecution of Christians began in the 1st century AD, and officially ended with the Edict of Toleration by Galerius in 311.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Laud, Anja (12 December 2024). "Sensationsfund in Frankfurt sorgt für Aufsehen bei Archäologen" [Sensational Discovery in Frankfurt Excites Archaeologists] (in German). Hessisch-Niedersächsische Allgemeine. Archived from the original on 14 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ "Frankfurter Silberinschrift: Ältestes christliches Zeugnis nördlich der Alpen gefunden" [Frankfurt Silver Inscription: Oldest Christian Evidence North of the Alps Found]. presseportal.de (in German). 11 December 2024. Archived from the original on 11 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ Huld-Zetsche, Ingeborg (1994). "Nida: eine römische Stadt in Frankfurt am Main". Schriften des Limesmuseums Aalen. 48: 24–25.

- ^ Hampel, Andrea (2018). Udo Recker (ed.). "Das Gräberfeld "Heilmannstraße" in Frankfurt a. M.-Praunheim". Hessen-Archäologie. Jahrbuch für Archäologie und Paläontologie in Hessen (2017). Wiesbaden: Landesamt für Denkmalpfege Hessen: 132–135. ISBN 978-3-8062-3810-5. Archived from the original on 14 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Zusätzliche Informationen zur Frankfurter Silberinschrift" [Additional information about the Frankfurt silver inscription] (in German). Archäologisches Museum Frankfurt. 2024. Archived from the original on 14 December 2024. Retrieved 14 December 2024.

- ^ a b c "Archäologischer Sensationsfund. "Der älteste Christ nördlich der Alpen war Frankfurter"". hessenschau.de (in German). 11 December 2024. Archived from the original on 13 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Altuntaş, Leman (13 December 2024). "'Frankfurt Silver Inscription' Archaeologists Unearth Oldest Christian Artifact North of the Alps". arkeonews.net. Archived from the original on 15 December 2024. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Pflughoeft, Aspen (12 December 2024). "Mysterious ancient amulet turns out to be oldest trace of Christianity north of Alps". The News Tribune. Archived from the original on 14 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ a b "Archaeologists uncover earliest Christian inscription north of the Alps in Frankfurt". The Jerusalem Post. 12 December 2024. Archived from the original on 14 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ "Archäologen haben ältestes christliches Zeugnis nördlich der Alpen entdeckt" [Archaeologists Discover Oldest Christian Evidence North of the Alps]. spiegel.de (in German). 11 December 2024. Archived from the original on 13 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ a b Kleindl, Reinhard (11 December 2024). "Silberamulett ist frühestes Zeugnis des Christentums nördlich der Alpen" [Silver amulet is the earliest evidence of Christianity north of the Alps] (in German). Archived from the original on 13 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Frankfurt silver inscription" – Oldest Christian testimony found north of the Alps (press release), Goethe University Frankfurt, 12 December 2024, archived from the original on 14 December 2024, retrieved 13 December 2024

- ^ a b "University of Bonn Researcher Involved in Sensational Find in Frankfurt". University of Bonn. 13 December 2024. Archived from the original on 14 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward (1781). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (PDF). Vol. 2. p. 576-577.

- ^ a b "Geschichte des Christentums neu schreiben?" [Rewrite the History of Christianity?]. evangelisch.de (in German). 11 December 2024. Archived from the original on 14 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ Moeed, Abdul (13 December 2024). "Early Christian Inscription Found in Northern Europe Rewrites History". Greek Reporter. Archived from the original on 13 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

External links

[edit]- Frankfurt am Main: Pressekonferenz zur Vorstellung eines archäologischen Sensationsfundes (Press conference on the presentation of a sensational archaeological discovery), 11 December 2024, YouTube (video, 57 minutes; a transcription of the text is shown at 25:41 minutes)

- Images of the virtually unrolled amulet, and the text of the inscription

- 2018 archaeological discoveries

- 3rd-century artifacts

- 3rd-century biblical manuscripts

- 3rd-century Christian texts

- 3rd century in Germany

- 3rd-century inscriptions

- 3rd century in the Roman Empire

- Amulets

- Archaeological discoveries in Germany

- Early Christian inscriptions

- Frankfurt

- Germania

- History of Christianity in Germany

- Silversmithing

- Latin inscriptions

- Silver objects

- Cultural depictions of Jesus

- Epistle to the Philippians