Evangelicalism in the United States

In the United States, evangelicalism is a movement among Protestant Christians who believe in the necessity of being born again, emphasize the importance of evangelism, and affirm traditional Protestant teachings on the authority as well as the historicity of the Bible.[1] Comprising nearly a quarter of the U.S. population, evangelicals are a diverse group drawn from a variety of backgrounds, including nondenominational churches, Pentecostal, Baptist, Reformed, Methodist, Mennonite, Plymouth Brethren, and Quaker.[2][3][4]

Evangelicalism has played an important role in shaping American religion and culture. The First Great Awakening of the 18th century marked the rise of evangelical religion in colonial America. As the revival spread throughout the Thirteen Colonies, evangelicalism united Americans around a common faith.[1] The Second Great Awakening of the early 19th century led to what historian Martin Marty calls the "Evangelical Empire", a period in which evangelicals dominated U.S. cultural institutions, including schools and universities. Evangelicals of this era in the northern United States were strong advocates of reform. They were involved in the temperance movement and supported the abolition of slavery, in addition to working toward education and criminal justice reform. In the southern United States, evangelicals split from their northern counterparts on the issue of slavery, establishing new denominations that opposed abolition and defended the practice of racial slavery[5] upon which the South's expanding cash-crops-for-export agricultural economy was built.[6][7][8] During the bloody Civil War, each side confidently preached in support of its own cause using Bible verses and Evangelical arguments, which exposed a deep theological conflict that had been brewing for decades and would continue long after Lee's surrender at Appomattox.[9]

By the end of the 19th century, the old evangelical consensus that had united much of American Protestantism no longer existed. Protestant churches became divided over ground-breaking new intellectual and theological ideas, such as Darwinian evolution and historical criticism of the Bible. Those who embraced these ideas became known as modernists, while those who rejected them became known as fundamentalists. Fundamentalists defended a doctrine of biblical inerrancy and adopted a dispensationalist theological system for interpreting the Bible.[10][11] As a result of the fundamentalist–modernist controversy of the 1920s and 1930s, fundamentalists lost control of the Mainline Protestant churches and separated themselves from non-fundamentalist churches and cultural institutions.[12]

After World War II, a new generation of conservative Protestants rejected the separatist stance of fundamentalism and began calling themselves evangelicals. Popular evangelist Billy Graham was at the forefront of reviving use of the term. During this time period, several evangelical institutions were established, including the National Association of Evangelicals, the magazine Christianity Today, and educational institutions such as Fuller Theological Seminary.[13] As a reaction to the 1960s counterculture and the U.S. Supreme Court's 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, many white evangelicals became politically active and involved in the Christian right,[14] which became an important voting bloc in the Republican Party. Recently, however, observers such as journalist Frances FitzGerald have noted that since 2005 the influence of the Christian right among evangelicals has been in decline.[15] Though less visible, some evangelicals identify as progressive evangelicals.[14]

Definition

[edit]Many scholars have adopted historian David Bebbington's definition of evangelicalism. According to Bebbington, evangelicalism has four major characteristics. These are conversionism (an emphasis on the new birth), biblicism (an emphasis on the Bible as the supreme religious authority), activism (an emphasis on individual engagement in spreading the gospel), and crucicentrism (an emphasis on Christ's sacrifice on the cross as the heart of true religion). However, this definition has been criticized for being so broad as to include all Christians.[16][17]

Historian Molly Worthen writes "history—rather than theology or politics—is the most useful tool for pinning down today's evangelicals."[18] She finds that evangelicals share common origins in the religious revivals and moral crusades of the 18th and 19th centuries. She writes, "Evangelical catchphrases like 'Bible-believing' and 'born again' are modern translations of the Reformers' slogan sola scriptura and Pietists' emphasis on internal spiritual transformation."[18]

Evangelicals are often defined in opposition to mainline Protestants. According to sociologist Brian Steensland and colleagues, "evangelical denominations have typically sought more separation from the broader culture, emphasized missionary activity and individual conversion, and taught strict adherence to particular religious doctrines."[19] Mainline Protestants are described as having "an accommodating stance toward modernity, a proactive view on issues of social and economic justice, and pluralism in their tolerance of varied individual beliefs."[20]

Historian George Marsden writes that during the 1950s and 1960s the simplest definition of an evangelical was "anyone who likes Billy Graham". During that period, most people who self-identified with the evangelical movement were affiliated with organizations that had some connection to Graham.[21] It can also be defined narrowly as a movement centered around organizations such as the National Association of Evangelicals and Youth for Christ.[17]

News media often conflate evangelicalism with "conservative Protestantism" or the Christian right. However, not every conservative Protestant identifies as evangelical, nor are all evangelicals political conservatives.[22]

Types

[edit]

Scholars have found it useful to distinguish among different types of evangelicals. One scheme by sociologist James Davison Hunter identifies four major types: the Baptist tradition, the Holiness and Pentecostal tradition, the Anabaptist tradition, and the Confessional tradition (evangelical Anglicans, pietistic Lutherans, and evangelicals within the Reformed churches).[23][24]

Ethicist Max Stackhouse and historians Donald W. Dayton and Timothy P. Weber divide evangelicalism into three main historical groupings. The first, called "Puritan" or classical evangelicalism, seeks to preserve the doctrinal heritage of the 16th century Protestant Reformation, especially the Reformed tradition. Classical evangelicals emphasize absolute divine sovereignty, forensic justification, and "literalistic" inerrancy. The second, pietistic evangelicalism, originates from the 18th-century pietist movements in Europe and the Great Awakenings in America. Pietistic evangelicals embrace revivalism and a more experiential faith, emphasizing conversion, sanctification, regeneration, and healing. The third, fundamentalist evangelicalism, results from the Fundamentalist–Modernist split of the early 20th century. Fundamentalists emphasize certain "fundamental" beliefs against modernist criticism and often use an apocalyptic, premillennialist interpretation of the Bible. These three categories are more fluid than Hunter's, so an individual could identify with only one, any two, or all three.[25]

John C. Green, a senior fellow at the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, used polling data to separate evangelicals into three broad camps, which he labels as traditionalist, centrist and modernist:[26]

- Traditionalist evangelicals, characterized by high affinity for certain Protestant beliefs, (especially penal substitutionary atonement, justification by faith, the authority of scripture, and the priesthood of all believers) which, when fused with the highly political milieu of Western culture (especially American culture), has resulted in the political disposition that has been labeled the Christian right, with public figures like Jerry Falwell and the television evangelist Pat Robertson among its most visible spokesmen.

- Centrist evangelicals, described as socially conservative and mostly avoiding politics, who still support much of traditional Christian theology.

- Modernist evangelicals, a small minority in the movement, who have lower levels of church attendance and "have much more diversity in their beliefs".[26]

History

[edit]18th century

[edit]The roots of American evangelicalism lie in the merger of three older Protestant traditions: New England Puritanism, Continental Pietism and Scotch-Irish Presbyterianism.[27] Within their Congregational churches, Puritans promoted experimental or experiential religion, arguing that saving faith required an inward transformation.[28] This led Puritans to demand evidence of a conversion experience (in the form of a conversion narrative) before a convert was admitted to full church membership.[29] In the 1670s and 1680s, Puritan clergy began to promote religious revival in response to a perceived decline in religiosity.[30] The Ulster Scots who immigrated to the American colonies in the early 18th century brought with them their own revival tradition, specifically the practice of communion seasons.[31] Pietism was a movement within the Lutheran and Reformed churches in Europe that emphasized a "religion of the heart": the ideal that faith was not simply acceptance of propositional truth but was an emotional "commitment of one's whole being to God" in which one's life became dedicated to self-sacrificial ministry.[32] Pietists promoted the formation of cell groups for Bible study, prayer, and accountability.[33]

These three traditions were brought together with the First Great Awakening, a series of revivals in Britain and its American Colonies during the 1730s and 1740s.[35] The Awakening began within the Congregational churches of New England. In 1734, Jonathan Edwards' preaching on justification by faith instigated a revival in Northampton, Massachusetts. Earlier Puritan revivals had been brief, local affairs, but the Northampton revival was part of a larger wave of revival that affected the Presbyterian and Dutch Reformed churches in the middle colonies as well.[36] There the Reformed minister Theodore Frelinghuysen and Presbyterian minister Gilbert Tennent led revivals.[34]

The English evangelist George Whitefield was responsible for spreading the revivals through all the colonies. An Anglican priest, Whitefield had studied at Oxford University prior to ordination, and there he befriended John Wesley and his brother Charles, the founders of a pietistic movement within the Church of England called Methodism. Whitefield's dramatic preaching style and ability to simplify doctrine made him a popular preacher in England, and in 1739 he arrived in America preaching up and down the Atlantic coastline. Thousands flocked to open-air meetings to hear him preach, and he became a celebrity throughout the colonies.[37]

The Great Awakening hit its peak by 1740,[38] but it shaped a new form of Protestantism that emphasized, according to historian Thomas S. Kidd, "seasons of revival, or outpourings of the Holy Spirit, and converted sinners experiencing God's love personally" [emphasis in original].[39] Evangelicals believed in the "new birth"—a discernible moment of conversion—and believed that it was normal for a Christian to have assurance of faith.[40] While the Puritans had also believed in the necessity of conversion, they "had held that assurance is rare, late and the fruit of struggle in the experience of believers".[41] Emphasis on the individual's relationship to God gave evangelicalism an egalitarian streak as well, which was perceived by anti-revivalists as undermining social order. Radical evangelicals ordained uneducated ministers (sometimes nonwhite men) and sometimes allowed nonwhites and women to serve as deacons and elders. They also supported laypeople's right to dissent from their pastors and form new churches.[42]

The Awakening split the Congregational and Presbyterian churches over support for the revival movement, between Old and New Lights, leading to the Old Side–New Side controversy. Ultimately, the evangelical New Lights became the larger faction among both Congregationalists and Presbyterians. The New England theology, based on Edwards' work, would become the dominant theological outlook within Congregational churches.[43][37] In New England, radical New Lights broke away from the established churches and formed Separate Baptist congregations. In the 1740s and 1750s, New Side Presbyterians and Separate Baptists began moving to the southern colonies and establishing churches. Many traveled along the difficult Great Wagon Road on their way to the southern colonies. There they challenged the Anglican religious establishment, which was identified with the planter elite. In contrast, evangelicals tended to be neither very rich nor very poor, but hardworking farmers and tradesmen who disapproved of worldliness they saw in the planter class. In the 1760s, the first Methodist missionaries came to America and focused their ministry in the South as well. By 1776, evangelicals outnumbered Anglicans in the South.[44]

During and after the American Revolution, the Anglican Church (now known as the Episcopal Church) experienced much disruption and lost its special legal status and privileges. The four largest denominations were the Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists. In the 1770s and 1780s, the Baptists and Methodists had experienced dramatic growth. In 1770, there were only 150 Baptist and 20 Methodist churches, but in 1790 there were 858 Baptist and 712 Methodist churches. These two evangelical denominations were most successful in the southern states and along the western frontier. They also appealed to African slaves; on the Delmarva Peninsula, for example, over a third of Methodists were black. In the 1790s, evangelical influence on smaller groups such as Quakers, Lutherans, and the Dutch and German Reformed was still limited. Because of cultural and language barriers, the Dutch and German churches were not a major part of this era's evangelical revivals.[45]

19th century

[edit]In the 19th century, evangelicalism expanded as a result of the Second Great Awakening (1790s–1840s).[46] The revivals of the Second Great Awakening influenced all the major Protestant denominations, and turned most American Protestants into evangelicals.[47] From the 1790s until the 1860s, evangelicals were the most influential religious leaders in the United States.[16] For context, the U.S. population was 2.6 million in 1776. By 1860 it had grown to 31.5 million. Between 1790 and 1840, over four million people (more than the entire population in 1776) had moved west of the Appalachian Mountains.[48]

There were three major centers of revival in the Second Great Awakening. Revival in the Cumberland River Valley of western frontier states Tennessee and Kentucky started as early as 1800. In New England, a major revival began among Congregationalists by the 1820s, led by Edwardsian preachers such as Timothy Dwight, Lyman Beecher, Nathaniel Taylor, and Asahel Nettleton. In western New York—the so-called "burned-over district" along the Erie Canal—the revival was mainly led by Congregationalists and Presbyterians, but Baptists and Methodists were also involved.[49]

Unlike the East Coast, where revivals tended to be quieter and more solemn, western revivals tended to be emotional and dramatic.[50] Presbyterian minister James McGready led the Revival of 1800, also known as the Red River Revival, in southwestern Kentucky's Logan County. It was here that the traditional Scottish communion season began to evolve into the American camp meeting.[51] In northeastern Kentucky's Bourbon County a year later, the Cane Ridge Revival led by Barton Stone lasted a week and drew crowds of 20,000 people from the thinly populated frontier. At Cane Ridge, many converts experienced religious ecstasy and "bodily agitations".[52] Some worshipers caught holy laughter, barked like dogs, experienced convulsions, fell into trances, danced, shouted or were slain in the Spirit. Similar responses had occurred in other revivals, but they were more intense at Cane Ridge. This revival was the origin of the Stone-Campbell Movement, from which the Churches of Christ and Disciples of Christ denominations originate.[53][52]

During the Second Great Awakening, the Methodist Episcopal Church was most successful at gaining converts. It enthusiastically adopted camp meetings as a regular part of church life, and devoted resources to evangelizing the western frontier. Itinerant ministers known as circuit riders traveled hundreds of miles each year to preach and serve scattered congregations. The Methodists took a democratic and egalitarian approach to ministry, allowing poor and uneducated young men to become circuit riders. The Baptists also expanded rapidly. Like the Methodists, Baptists also sent out itinerant ministers, often with little education.[54]

The theology behind the First Great Awakening had been largely Calvinist.[55] Calvinists taught predestination and that God only gives salvation to a small group of the elect and condemns everyone else to hell. The Calvinist doctrine of irresistible grace denied to humans free will or any role in their own salvation.[56] The Second Great Awakening was heavily influenced by Arminianism, a theology that allows for free will and gives humans a greater role in their own conversion.[55] The Methodists were Arminians and taught that all people could choose salvation. They also taught that Christians could lose their salvation by backsliding or returning to sin.[56]

The most influential evangelical of the Second Great Awakening was Charles Grandison Finney. He is best known for preaching from 1825 to 1835 in Upstate New York,[57] which experienced a population boom after the Erie Canal opened in 1825.[58] Though ordained by the Presbyterian Church, Finney deviated from traditional Calvinism. Finney taught that neither revivals nor conversion occurred without human effort. While divine grace is necessary to persuade people of the truth of Christianity, God does not force salvation upon people. Unlike Edwards, who described revival as a "surprising work of God", Finney taught that "revival is not a miracle" but "the result of the right use of the appropriate means."[59] Finney emphasized several methods to promote revival that became known as the "new measures" (even though they were not new but had already been in use among the Methodists): mass advertising, protracted revival meetings, allowing women to speak and testify in revival meetings, and the mourner's bench where potential converts sat to pray for conversion.[60] Finney was also active in social reforms, particularly the abolitionist movement. He frequently denounced slavery from the pulpit, called it a "great national sin," and refused Holy Communion to slaveholders.[61]

Evangelical views on eschatology (the doctrine of the end times) have also changed over time. The Puritans were premillennialists, which means they believed Christ would return before the Millennium (a thousand years of godly rule on earth). But the First Great Awakening convinced many evangelicals that the millennial kingdom was already being established before Christ returned, a belief known as postmillennialism. During the Second Great Awakening, postmillennialism (with its expectation that society would become progressively more Christianized) became the dominant view, since it complemented the Arminian emphasis on self-determination and the Enlightenment's positive view of human potential.[62]

This postmillennial optimism inspired a number of social reform movements among northern evangelicals,[63] including temperance (as teetotalism became "a badge of honor" for evangelicals),[64] abolitionism, prison reform, and educational reform.[62] They launched a campaign to end dueling.[65] They built asylums for the physically disabled and mentally ill, schools for the deaf, and hospitals for treating tuberculosis. They formed organizations to provide food, clothing, money, and job placement to immigrants and the poor.[66] In order to "impress the new nation with an indelibly Protestant character," evangelicals founded Sunday schools, colleges, and seminaries. They published millions of books, tracts, and Christian periodicals through organizations such as the American Tract Society and the American Bible Society.[65] This network of social reform organizations is referred to as the Benevolent Empire.

Postmillennialism also led to an increase in missionary work.[62] Many of the major missionary societies in the U.S. were founded around this time. Missionary efforts by northern evangelicals included the influential American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), founded in 1810, which sent missionaries overseas, placed missionaries with American Indian tribes in the Southeastern United States, and had established missions among the Cherokee, for example, by 1820. The ABCFM fought against U.S. Indian removal policies in general and against the Indian Removal Act of 1830 in particular.[67] In 1836 the ABCFM sent Marcus and Narcissa Whitman west from Upstate New York to preach to the Cayuse people in Oregon Country.[68][69]

The Third Great Awakening that began in 1857–1858 also gathered much of its strength from the postmillennial belief that the Second Coming of Christ would occur after mankind had reformed the entire Earth. It was affiliated with the Social Gospel movement, which applied Christianity to social issues.[70]

Dispensationalism

[edit]

The spread of dispensationalism in late 19th-century America led many Evangelicals to return to the more pessimistic premillennialist point of view. According to scholar Mark Sweetnam, dispensationalists are evangelical, premillennialist and apocalyptic, insist on a literal interpretation of Scripture, identify distinct stages ("dispensations") in God's dealings with humanity, and expect Christ's imminent return to rapture His saints.[71] As B. M. Pietsch notes, their leaders have built intricate new methods of text analysis to "unlock" the Bible's meaning.[72]

John Nelson Darby was an austere 19th-century Anglo-Irish Bible teacher and former Anglican clergyman who devised and promoted dispensationalism. This new and controversial method of interpreting the Bible,[73][74] which does not reconcile easily with findings from recent mainstream archaeological and textual research,[75][76][77] was incorporated into the development of modern Evangelicalism.[78] First taught in the 1830s by Darby and the Plymouth Brethren in England, dispensationalism was introduced to American evangelical leaders during Darby's missionary journeys to the U.S. and Canada in the 1860s and 1870s.[79] The Niagara Bible Conference was organized in 1876 to teach dispensationalist ideas;[80] these ideas came to dominate the fundamentalist movement within a few decades.[11][81]

Dwight L. Moody played a key role in this transformation. In the latter half of the 19th century, Moody became the most important evangelical figure of the era, weaving ideas from business and religion into a compelling new form of evangelical Protestantism and reaching very large audiences with his powerful preaching.[82][83][84][85] Focused on the city of Chicago and active in the Sunday School movement and Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) from 1858 in his early ministry, Moody had relentlessly sought financial contributions from rich evangelical businessmen such as John Farwell and Cyrus McCormick. Moody's approach was rough, blunt and unconventional, but wealthy philanthropists could see he truly cared for the urban poor and he found effective ways to improve their lot.[86][83] During an 1867 visit to England, Moody became acquainted with a group of pragmatic Brethren dispensationalists who shared many of his own concerns and approaches to charitable work.[87] After the Great Chicago Fire in 1871 destroyed his church, his home and the Chicago YMCA, Moody left local church work for a new career as a traveling revivalist.[83] Convinced now that the world would be changed not by social work but by Christ's return and the establishment of His millennial kingdom on Earth, Moody abandoned his own previous postmillennialist views.[83] His revivals accelerated the spread of dispensationalist beliefs, and he was influential in preaching the imminence of the Kingdom of God that is so important to dispensationalism.[88]

Enlisting philanthropic support from the business community was one of several enduring innovations Moody had introduced into the conduct of revival campaigns.[83] Like many clergymen in the Gilded Age that followed soon after the Civil War, Moody supported the business community's values. He helped forge the union between the evangelical mind and the business mind that came to be a hallmark of later popular revivalists.[89] Moody's religious individualism fit neatly with the rugged individualism of Gilded Age businessmen.[90] Moody radiated optimism when he spoke about how Christian conversion would impact a poor man's life.[91] He believed Christian conversion would make lazy, poor men into energetic men who would then work hard and prosper.[91] At his revival meetings Moody would look around at the wealthy men who sat on the platform with him, such as McCormick, William E. Dodge, and John Wanamaker, comment that they were all devout church members, all born again Christians, and say that few of the poor in the slums of Chicago, London, or New York attended church services.[91] Moody also viewed industrialism and its ills through the same lens of Christian conversion. As he saw it, the fix was simple and obvious: believe in God, and the problems will vanish soon.[92]

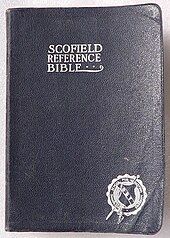

American evangelical minister and Moody associate Cyrus Scofield also promoted the spread of dispensationalism, starting with a pamphlet published in 1888, then by weaving extensive interpretive commentary into prominent notes on the pages of his ambitious Scofield Reference Bible. First published in 1909, the Scofield Bible became a popular one-volume reference used widely by independent Evangelicals in the United States.[93] It did much to popularize dispensationalism early in the 20th century, as Evangelicals sought to make sense of calamities like World War I, the 1918 influenza pandemic, the 1929 stock market crash, the Great Depression and Dust Bowl in the 1930s, and World War II. By 1945, more than 2 million copies had been published in the United States.[94]

Evangelicals also launched a network of independent Bible institutes which soon became the nucleus for the spread of American dispensationalism.[95] Notable examples include the Moody Bible Institute[96] and the Bible Institute of Los Angeles.[97] By the early 1930s there were as many as fifty such Bible institutes serving fundamentalist constituencies.[95]

Holiness Movement

[edit]In the late 19th century, the revivalist Holiness movement promoted the doctrine of entire sanctification, and while many adherents remained within mainline Methodism, those associated with it also formed new denominations, such as the Free Methodist Church and Wesleyan Methodist Church.[98] In urban Britain the holiness message was less censorious, and did not face as much opposition.[99]

Princeton Theologians

[edit]From the 1850s to the 1920s, a more technical theological perspective came from the Princeton Theologians, such as Charles Hodge, Archibald Alexander, and B. B. Warfield,[100] who strove to defend traditional doctrines they found in the Bible against rival claims from other learned scholars, including such claims that were based on higher criticism.[101]

20th century

[edit]

By the 1890s, most American Protestants belonged to evangelical denominations, except for high church Episcopalians and German Lutherans. In the early 20th century, a divide opened up between fundamentalists and the mainline Protestant denominations, chiefly over inerrancy of the Bible. After 1910, evangelicalism was dominated by fundamentalists who rejected liberal theology, emphasized inerrancy of Scripture, and taught a dispensationalist interpretation of the Bible to support their views of human history and mankind's future.

Pastors, theologians, and laity shaped the course of early fundamentalism, but wealthy businessmen also played a crucial role.[102][103] For example, Union Oil co-founder Lyman Stewart was instrumental in establishing the Bible Institute of Los Angeles.[97][104] He also anonymously funded publication and distribution of The Fundamentals (groups of essays by multiple authors published quarterly in twelve volumes from 1910 through 1915), which became the foundation document of Christian fundamentalism, published as a set in 1917,[103][105][106] and he ensured that its many individual authors promoted premillennialist dispensationalism.[103][105] The essays were written by 64 different authors, representing most of the major Protestant Christian denominations. It was mailed free of charge to ministers, missionaries, professors of theology, Sunday school superintendents, YMCA and YWCA secretaries, and other Protestant religious workers in the United States and other English-speaking countries. Over three million volumes (250,000 sets) were sent out.[105]

Dispensationalism led fundamentalist evangelicals to see the world as a battleground in a deadly conflict between God and the Devil that would sweep all unbelievers to perdition very soon, so that they must focus on saving souls, with reform of society as a strictly secondary concern.[107] Adoption of this "lifeboat" theology also made the fundamentalists' message more welcome among American groups and communities who opposed reform of their own cherished institutions (such as violent enforcement of racial segregation by local authorities and by self-appointed vigilante groups) and business practices (ruthless exploitation of industrial workers,[108] redlining, and the Jim Crow economy).[109]

Dispensationalism also led fundamentalists to fear that new trends in modern science were pulling people away from what they saw as essential truth, and to believe that modernist parties in Protestant churches had surrendered their Evangelical heritage by accommodating secular views and values. Among these fundamentalist evangelicals, a favored way of resisting modernism was to prohibit teaching evolution as fact in public schools, a movement that reached a peak in the Scopes trial of 1925. The sting of this public embarrassment led fundamentalists to retreat further into separatism. Protestant modernists criticized fundamentalists for their separatist self-isolation and for their rejection of the Social Gospel that had been developed by Protestant activists in the previous century. By this time, modernists had largely abandoned the term "evangelical," and tolerated evolutionary theories in modern science and even in Biblical studies. In the 1930s, fundamentalist pastors and parishioners who rejected modernist viewpoints put forward by their own denominations turned more and more to the dispensationalist Bible institutes for guidance and community.[110] As the largest of these schools, the Moody Bible Institute set the pace, providing a wide variety of fundamentalist outreach services, from guest speakers and extension courses to Bible conferences, magazines and radio programs.[110][111]

During and after World War II, white evangelicals formed new organizations and expanded their vision to include the entire world. There was a great expansion of Evangelical activity within the United States, "a revival of revivalism." The doctrine of dispensationalism, with its intense focus on end times and the rapture, continued to be a major theme. Many earlier evangelists had preached in tents to small-town audiences on the "sawdust trail," but the new evangelicals sought ways to save souls in the big cities that had come to dominate American life.[112] Youth for Christ was formed in 1940 to help make the evangelical message attractive to soldiers, sailors, and urban teenagers;[113] it later became the base for Billy Graham's post-war revival crusades.[114][115] The National Association of Evangelicals was formed in 1942 as a response to the mainline Federal Council of Churches, which had been organized in 1908.[112] Charles Fuller had started broadcasting the Old-Fashioned Revival Hour in 1937; by 1943 it had a record-setting national radio audience, with twenty million weekly listeners.[112]

But a split also developed among evangelicals in this era, as they disagreed among themselves about how a Christian ought to respond to an unbelieving world. Many evangelicals urged that Christians must engage contemporary culture directly and constructively,[116] and they began to express reservations about being known to the world as fundamentalists. As Kenneth Kantzer put it at the time, the name fundamentalist had become "an embarrassment instead of a badge of honor".[117] Fuller Theological Seminary founding president Harold Ockenga coined the term neo-evangelicalism in 1947 to identify a distinct movement he saw within fundamentalist Christianity. This new generation of evangelicals sought to pursue a more open, non-judgmental dialogue with other traditions. They also called for greater application of the gospel to sociology, politics, and economics. Many fundamentalists responded by separating their opponents from the "fundamentalist" name and by seeking to distinguish themselves from the more open group, which they often characterized derogatorily by Ockenga's term "neo-Evangelical", or simply "evangelicals".

Growth during the Cold War

[edit]

The end of World War II in 1945 and the onset of the Cold War by 1948 provided new opportunities for evangelical expansion. The Second World War ended in August 1945 after the U.S. used two nuclear bombs to destroy the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Even nonreligious people groped for religious language to express those bombs' nearly unimaginable destructive power.[118] And the end of the war affected almost everyone in America: millions of men returned from the armed forces, while millions of women left their temporary wartime industrial jobs. The marriage rate and the birth rate soared, accelerating a baby boom that had begun while the war was still being fought.[119] As young American families crowded into new churches, their ministers, priests, and rabbis led them in fervent prayers for a world in upheaval.[119] No one in the U.S. voiced fears for the world's future with more fervor than evangelical and fundamentalist preachers. A key element in their preaching had always been that the Second Coming of Christ could happen at any moment and that everyone must be ready for the end of the world.[119]

In September 1949, 30-year-old evangelist Billy Graham set up circus tents in a Los Angeles parking lot for a series of revival meetings. A tall, handsome, spellbinding preacher from North Carolina with a piercing gaze, Graham aimed to fill his listeners first with dread that they were lost sinners in a world rushing headlong into disaster, then with a deep longing to turn their lives around, trust Jesus, and be saved.[113] The crusade started on September 25, 1949,[120] and it was scheduled to last three weeks, from September 25 to October 17.[121] Two days before the start of the revival, in a statement released on September 23, 1949, President Truman revealed to the public that the communist Soviet Union had built and successfully detonated its own nuclear bomb on August 29.[122] Six days after the revival started, mainland China fell to Mao Zedong's communist Red Army.[123] Newspaper headlines that reported these shocking Cold War events put much of the nation into an anxious, apocalyptic mood. Then in October, media tycoon[124] William Randolph Hearst sent a telegram to all editors in his conservative Hearst chain of newspapers: "Puff Graham."[125][126] As a result, within five days Graham gained national coverage.[127][128] Planned to last three weeks, the event ran for eight weeks. Graham became a national figure with heavy coverage from the wire services and national magazines, and he went on to become the most influential American evangelist of the 20th century.

Evangelicals' international missionary activity also expanded in the postwar era. White evangelicals found new enthusiasm and self-confidence after the nation's victory in the world war. Many came from poor rural districts that had struggled during the Great Depression of the 1930s, but wartime and postwar prosperity had dramatically increased the funding resources available for missionary work. Overseas missionaries began to prepare for their postwar role, in organizations such as the Far Eastern Gospel Crusade. After Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan had been defeated, the newly mobilized evangelicals prepared to combat perceived threats from atheistic communism, secularism, Darwinism, liberalism, Catholicism, and (in overseas missions) paganism.[129]

While mainline Protestant denominations cut back on their missionary activities from 7,000 overseas workers in 1935 to only 3,000 in 1980, evangelicals tripled their career foreign missionary force in the same period: from 12,000 in 1935 to 35,000 in 1980. At Youth for Christ's 70,000-person rally on Memorial Day 1945 in Chicago's Soldier Field football stadium (seating capacity 74,000), soldiers and nurses marched along with missionary representatives who paraded in costumes representing all the nations still awaiting the dispensationalist gospel.[113][130] North Americans had sent out only 41% of all the world's Protestant missionaries in 1936, but their contribution rose to 52% in 1952 and 72% in 1969. Denominations expanding their overseas missionary efforts after the war included the United Pentecostal Church International, formed in 1945, and the Assemblies of God, which nearly tripled from 230 missionaries in 1935 to 626 in 1952. Southern Baptist missionaries more than doubled from 405 to 855, as did those sent by the Church of the Nazarene, from 88 to 200.[131]

The post-war period also saw growth of the ecumenical movement and the founding of the World Council of Churches (1948), which was generally regarded with suspicion by the evangelical community.[132] During the 1950s, the number of church members in America grew from 64.5 million to 114.5 million. By 1960, more than 60% of the nation belonged to a church.[133] Following the Welsh Methodist revival, the Azusa Street Revival in 1906 had begun the spread of Pentecostalism in North America. The Charismatic movement began in the 1960s and led to Pentecostal theology and practices being introduced into many mainline denominations. Charismatic groups such as Newfrontiers and the Association of Vineyard Churches trace their roots to this period.

21st century

[edit]

A 2018 report of polls conducted from 2003 to 2017 of 174,485 random-sample telephone interviews by ABC News and The Washington Post show significant shifts in U.S. religious identification in those 15 years, including a decline in the share of Americans who identify as Protestants (both evangelical and non-evangelical) and a rise in the share of Americans who say they have no religion.[134] According to reports in the New York Times, some evangelicals have sought to expand their movement's social agenda to include reducing poverty, combating AIDS in the Third World, and protecting the environment: "a push to better this world as well as save eternal souls."[135] This has been highly contentious within the evangelical community, because evangelicals of a more conservative stance believe this trend compromises important issues, and values popularity and consensus too highly: "a 'capitulation' to the broader culture."[135] Personifying this division in the early 21st century were the evangelical leaders James Dobson and Rick Warren. Dobson warned of dangers, from his point of view, of a victory by Democratic Party presidential candidate Barack Obama in 2008.[136] Warren declined to endorse either major candidate, on the grounds that he wanted the church to be less politically divisive and that he agreed substantially with both Obama and Republican Party candidate John McCain.[137]

Demographics

[edit]

Anywhere from 6 to 35% of the United States population is evangelical, depending on how "evangelical" is defined.[138] A 2008 study reported that in 2000, about 9% of Americans attended an evangelical service on any given Sunday.[139] A 2014 Pew Research Center survey of religious life in the United States reported that 25.4% of the population were evangelical, while Roman Catholics were 20.8% and mainline Protestants were 14.7%.[140] In 2020, mainline Protestants were reported to outnumber predominantly-white Evangelical churches.[141][142] In 2021, Pew Research Center reported that "24% of U.S. adults describe themselves as born-again or evangelical Protestants."[143]

In 2007 Barna Group reported that 8% of adult Americans were born-again evangelicals, defined as those surveyed in 2006 who answered yes to these nine questions:[144][138]

- "Have you made a personal commitment to Jesus Christ that is still important in your life today?"

- "Do you believe that when you die you will go to Heaven because you have confessed your sins and have accepted Jesus Christ as your savior?"

- "Is your faith very important in your life today?"

- "Do you have a personal responsibility to share your religious beliefs about Christ with non-Christians?"

- "Does Satan exist?"

- "Is eternal salvation possible only through grace, not works?"

- "Did Jesus Christ live a sinless life on earth?"

- "Is the Bible accurate in all that it teaches?"

- "Is God the all-knowing, all-powerful, perfect deity who created the universe and still rules it today?"

In 2012, The Economist estimated that "over one-third of Americans, more than 100 million, can be considered evangelical," arguing that the percentage is often undercounted because many African Americans espouse evangelical theology but refer to themselves as "born again Christians" rather than "evangelical."[145] As of 2017, according to The Economist, white evangelicals overall account for about 17% of Americans, while white evangelicals under the age of 30 represent about 8% of Americans in that age group.[146]

In 2016, Wheaton College's Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals estimated that about 30–35% (90 to 100 million people) of the U.S. population is evangelical. These figures include white and black "cultural evangelicals" (Americans who do not regularly attend church but identify as evangelicals).[147] Similarly, a 2019 Gallup survey asking respondents whether they identified either as "born-again" or as "evangelical" found that 37% of respondents answered in the affirmative.[148]

Sometimes members of historically black churches are counted as evangelicals, and at other times they are not. When analyzing political trends, pollsters often distinguish between white evangelicals (who tend to vote for the Republican Party) and African American Protestants (who share religious beliefs in common with white evangelicals but have tended to vote for the Democratic Party).[138][149]

Politics and social issues

[edit]Political ideology among American Evangelicals[150]

Evangelical political influence in America was first evident in the 1830s with movements such as the prohibition movement, which closed saloons and taverns in state after state until it succeeded nationally in 1919.[151] The Christian Right is a coalition of numerous groups of traditionalist and observant church-goers of many kinds: especially Catholics on issues such as birth control and abortion, plus Southern Baptists, Missouri Synod Lutherans, and others.[152] Since the early 1980s the Christian Right has been associated with several political and issue-oriented organizations, including the Moral Majority, the Christian Coalition, Focus on the Family, and the Family Research Council.[153][154]

In the 2016 presidential election, exit polls reported that 81% of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump,[155] despite criticism from some conservative evangelicals.[156][157][158]

Most African Americans who identify as Christians belong to Baptist, Methodist or other denominations that share evangelical beliefs, but they are firmly in the Democratic coalition, and (with the possible exception of issues involving abortion and homosexuality) are generally liberal in politics.[159][149]

Evangelical political activists are not all on the right. There is also a small group of liberal white Evangelicals.[14][160][161] Some Evangelical leaders, such as Tony Perkins of the Family Research Council, object to equating the term Christian Right with theological conservatism and Evangelicalism. Although white evangelicals constitute the core constituency of the Christian Right within the United States, not all evangelicals fit that political description. Secular media do frequently conflate the Christian Right with theological conservatism, but this becomes complicated when the label religious conservative or conservative Christian is also applied to other religious groups who are theologically, socially, and culturally conservative but do not have overtly political organizations associated with them. Some of these Christian denominations may best be described as indifferent toward politics.[162][163] Tim Keller, an Evangelical theologian and Presbyterian Church in America pastor, has argued that Conservative Christianity (theology) predates the Christian Right (politics), that being a theological conservative does not necessitate being a political conservative, and that some politically progressive views around economics, racial diversity, helping the poor, and the redistribution of wealth are compatible with theologically conservative Christianity.[164][165] Rod Dreher, a senior editor for The American Conservative, a secular conservative magazine, argues for the same distinctions, even claiming that a "traditional Christian," a theological conservative, can be an economic progressive or even a socialist while maintaining traditional Christian beliefs.[166]

On the other hand, a Pew Research report published in September 2022 reported that "70% of adults who were raised Christian but are now unaffiliated are Democrats or Democratic-leaning independents, compared with 43% of those who remained Christian and 51% of U.S. adults overall. Some scholars argue that disaffiliation from Christianity is driven by an association between Christianity and political conservatism that has intensified in recent decades."[167]

Another Pew Research report published in 2021 showed that between 2016 and 2020, the number of white Americans who started identifying as evangelical increased.[168] Ryan Burge, an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University and Baptist pastor, notes that a significant amount of Americans who have begun to embrace the evangelical identity are people who self-report as "never" or "seldom" attending church. Burge also notes there is a rise in people who are embracing the identity of "evangelical" but have no attachment to Protestant Christianity, such as Catholics, Muslims, and even Orthodox Christians, Hindus and members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[169]

Evolution

[edit]Evangelicals often reject mainstream scientific views out of concern that those views contradict traditional "young earth" chronologies and certain verses in the Bible. Scofield-inspired dispensationalists and other fundamentalists reject evolution in favor of creation science and flood geology (both of which contradict the scientific consensus and the well-established geologic time scale).[170] Their influence has led to high-profile court cases over whether public schools can be forced to teach either creationism or intelligent design (which is the claim that the complexity and diversity of life can only be explained by the direct intervention of God or some other active intelligence).[171][172]

However, other evangelicals have found evolution to be compatible with Christianity. For example, prominent evangelicals such as Billy Graham, B. B. Warfield, and John Stott believed the theory could be reconciled with Christian teaching.[173] Careful study by the American Scientific Affiliation, an organization for evangelicals who are professional scientists,[174] led it to reject "strict" creationism in favor of theistic evolution, encouraging acceptance of evolution among evangelicals.[175] The BioLogos Foundation is an evangelical organization that advocates for evolutionary creation, a belief that God brings about his plan through processes of evolution.[176] BioLogos expresses the belief that God is the source of all life and that life expresses the will of God. BioLogos represents the view that science and faith co-exist in harmony.[177]

Abortion

[edit]Since 1980, a central issue motivating conservative evangelicals' political activism has been abortion. The 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade by the Supreme Court, which legalized abortion at a federal level, proved to be decisive in bringing Catholics and evangelicals together in a political coalition, which became known as the Christian Right when it successfully mobilized its voters behind presidential candidate Ronald Reagan in 1980.[178]

Separation of church and state

[edit]

Supreme Court decisions that outlawed organized prayer in public schools and restricted church-related schools (e.g., preventing them from engaging in racial discrimination while also receiving a tax exemption) also played a role in mobilizing the Christian Right.[179] Survey data published in 2002 indicate that "between 31 and 39% do not favor a 'Christian Nation' amendment," but that 60 to 75% of Evangelicals consider Christianity and political liberalism to be incompatible.[180]

A study conducted in May 2022 showed that the strongest support for declaring the United States a Christian Nation comes from Republicans who identify as Evangelical or born-again Christians.[181][182] Of this demographic group, 78% are in favor of formally declaring the United States a Christian nation, versus 48% of Republicans overall.[181][183]

Climate change

[edit]The Evangelical Climate Initiative is a campaign by U.S. church leaders and organizations to promote market based mechanisms to mitigate global warming. The Evangelical Climate Initiative was launched in February 2006 by the National Association of Evangelicals, who worked with the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard Medical School to bring scientists and evangelical Christian leaders together for the project.[184] Young Evangelicals for Climate Action "educates and mobilizes young evangelical Christians across the country to take action to address the climate crisis."[185][186][187][188][189]

Influence on U.S. foreign policy

[edit]Evangelicals have had a significant impact on U.S. foreign policy. They have worked in coalitions with other religious and secular groups to press for action on matters like ending Sudan's civil war, addressing the AIDS crisis in Africa, and combating human trafficking.[190] Evangelicals played a key role in passing the International Religions Freedom Act, which made freedom of religion and conscience a top objective of U.S. foreign policy. The act established an agency to monitor countries' performance on religious freedom and allowed for potential sanctions against those with poor grades.[191] Evangelicals were also involved in the passing of the North Korean Human Rights Act of 2004, which required the appointment of a special envoy for human rights in North Korea and emphasized the importance of human rights in future negotiations with the country.[190] Evangelicals also supported the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, which aimed to deter human trafficking, punish traffickers, and protect and rehabilitate victims.[190]

Evangelicals generally view the Middle East through a dispensationalist biblical lens and strongly support Israel. They believe that God gave the land of Israel to the Jews and that the U.S. will be blessed if it blesses Israel. However, there are variations in views among Evangelicals, with some holding more rigid stances than others. Some have supported Israeli settlements in the occupied territories, and others disagree with certain peace initiatives that involve territorial compromises.[192]

See also

[edit]- Biblical literalism

- Broad church

- Child evangelism movement

- Christianese

- Christianity in the United States

- List of evangelical Christians

- List of evangelical seminaries and theological colleges

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b FitzGerald 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Angell, Stephen Ward; Dandelion, Pink (April 19, 2018). The Cambridge Companion to Quakerism. Cambridge University Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-1-107-13660-1.

Contemporary Quakers worldwide are predominately evangelical and are often referred to as the Friends Church.

- ^ FitzGerald 2017, p. 2.

- ^ Vickers 2013, p. 27.

- ^ FitzGerald 2017, p. 4-5.

- ^ Emerson & Smith 2001, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Johnson 2013, p. 10.

- ^ Hannah-Jones 2021, p. 16.

- ^ Noll 2006, pp. 1–7.

- ^ FitzGerald 2017, p. 5.

- ^ a b Hummel 2023, p. 1.

- ^ Marsden 1991, pp. 3–4.

- ^ FitzGerald 2017, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b c Miller 2014, pp. 32–59.

- ^ FitzGerald 2017, pp. 8–10.

- ^ a b Noll 2002, p. 5.

- ^ a b "Defining the Term in Contemporary Context", Defining Evangelicalism, Wheaton College: Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals, archived from the original on June 14, 2016, retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ a b Worthen 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Steensland et al. 2000, p. 249.

- ^ Steensland et al. 2000, p. 248.

- ^ Marsden 1991, p. 6.

- ^ Woodberry & Smith 1998, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Dorrien 1998, p. 2.

- ^ Ellingsen 1991, p. 234.

- ^ Dorrien 1998, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Luo, Michael (April 16, 2006). "Evangelicals Debate the Meaning of 'Evangelical'". The New York Times.

- ^ Balmer 2002, pp. vii–viii.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, p. 31.

- ^ Youngs 1998, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Kidd 2007, Chapter 1, Amazon Kindle location 148–152.

- ^ Kidd 2007, p. 31.

- ^ Kidd 2007, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, p. 34.

- ^ a b Sweeney 2005, p. 44.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, p. 27.

- ^ FitzGerald 2017, p. 14–18.

- ^ a b FitzGerald 2017, p. 18.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, pp. 44, 48.

- ^ Kidd 2007, p. xiv.

- ^ Kidd 2007, Introduction, Amazon Kindle location 66.

- ^ Bebbington 1993, pp. 43.

- ^ Kidd 2007, Introduction, Amazon Kindle location 79–82.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, p. 59.

- ^ FitzGerald 2017, pp. 22–25.

- ^ Wolffe 2007, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Wolffe 2007, p. 47.

- ^ FitzGerald 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, p. 189.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, pp. 66–71.

- ^ Wolffe 2007, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Wolffe 2007, p. 58.

- ^ a b FitzGerald 2017, p. 26.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, p. 72.

- ^ FitzGerald 2017, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Sweeney 2005, p. 66.

- ^ a b FitzGerald 2017, p. 31.

- ^ Johnson 2004, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Johnson 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Balmer 2002, p. 491.

- ^ FitzGerald 2017, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Balmer 1999, p. 47–48.

- ^ Johnson 2004, pp. 5–8.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, p. 75.

- ^ a b Sweeney 2005, p. 74.

- ^ FitzGerald 2017, p. 45.

- ^ Andrew 1992, p. unknown.

- ^ Miller 2003, pp. 79–84.

- ^ Harden 2021.

- ^ McLoughlin 1980, p. unknown.

- ^ Sweetnam, Mark S (2010), "Defining Dispensationalism: A Cultural Studies Perspective", Journal of Religious History, 34 (2): 191–212, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.2010.00862.x.

- ^ Pietsch 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Pietsch 2015, p. 2.

- ^ Gloege 2015, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Finkelstein 2013, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Sivertsen 2009, pp. 1–9.

- ^ Römer & Geuss 2015, pp. 9-23 and p. 293 note 1.

- ^ Grem 2016, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Sandeen 1970, pp. 70–79.

- ^ Dayton 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Hiett 2003, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Gloege 2015, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e Maas 1990, p. unknown.

- ^ Bebbington, David W (2005), Dominance of Evangelicalism: The Age of Spurgeon and Moody

- ^ Findlay, James F (1969), Dwight L. Moody: American Evangelist, 1837–1899.

- ^ Gloege 2015, p. 24.

- ^ Gloege 2015, p. 30.

- ^ Kee, Howard Clark; Emily Albu; Carter Lindberg; J. William Frost; Dana L. Robert (1998). Christianity: A Social and Cultural History. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 484.

- ^ Grem 2016, pp. 19–21.

- ^ Chartier 1969, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Chartier 1969, p. 22.

- ^ Chartier 1969, p. 28.

- ^ Pietsch 2015, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Allis 1945, p. 267.

- ^ a b Carpenter 1999, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Grem 2016, p. 20.

- ^ a b Grem 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Winn, Christian T. Collins (2007). From the Margins: A Celebration of the Theological Work of Donald W. Dayton. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-63087-832-0.

In addition to these separate denominational groupings, one needs to give attention to the large pockets of the Holiness movement that have remained within the United Methodist Church. The most influential of these would be the circles dominated by Asbury College and Asbury Theological Seminary (both in Wilmore, KY), but one could speak of other colleges, innumerable local camp meetings, the vestiges of various local Holiness associations, independent Holiness oriented missionary societies and the like that have had great impact within United Methodism. A similar pattern would exist in England with the role of Cliff College within Methodism in that context.

- ^ Bebbington, David W (1996), "The Holiness Movements in British and Canadian Methodism in the Late Nineteenth Century", Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, 50 (6): 203–28.

- ^ Hoffecker, W. Andrew (1981), Piety and the Princeton Theologians, Nutley: Presbyterian & Reformed, v.

- ^ Noll 1987, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Gloege 2015, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Grem 2016, p. 21.

- ^ History and Heritage - Biola University, retrieved November 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c Marsden 2006, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Sandeen 1970, p. unknown.

- ^ Allitt 2003, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Gloege 2015, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Mathews 2017, p. 1.

- ^ a b Carpenter 1999, p. 17.

- ^ Gloege 2015, pp. 227–228.

- ^ a b c Allitt 2003, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Allitt 2003, p. 14.

- ^ Grem 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica - Billy Graham biography, britannica com, retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ Henry, Carl FH (August 29, 2003) [1947], The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism (reprint ed.), Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, p. xvii, ISBN 0-8028-2661-X.

- ^ Zoba, Wendy Murray, The Fundamentalist-Evangelical Split, Belief net, retrieved July 1, 2005.

- ^ Allitt 2003, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Allitt 2003, p. 12.

- ^ Barry M. Horstmann (June 27, 2002). "Billy Graham: A Man With A Mission Impossible.(Special Section)". Cincinnati Post. Archived from the original on August 29, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ "Billy Graham Greater Los Angeles Campaign". Washington at Hill: Christ for Greater Los Angeles. 1949.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Statement by President Truman in Response to First Soviet Nuclear Test," September 23, 1949, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Department of State Bulletin, Vol. XXI, No. 533, October 3, 1949., retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ Watershed: Los Angeles 1949, retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ William Randolph Hearst - Biography, Facts & Career - History.com Editors, Nov 30, 2021, November 30, 2021, retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ Ben Bagdikian, The Media Monopoly, Boston, Mass: Beacon Press, 2000 6th ed., p. 39 ff.

- ^ 70th Anniversary – Greater Los Angeles Billy Graham Crusade of 1949 - September 25, 2019, September 25, 2019, retrieved November 21, 2022.

- ^ King, Randall E. (March 22, 1997). "When worlds collide: politics, religion, and media at the 1970 East Tennessee Billy Graham Crusade". Journal of Church and State. 39 (2): 273–295. doi:10.1093/jcs/39.2.273. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ Bagdikan (2000), Media Monopoly, p. 39

- ^ Miller-Davenport 2013, p. 1110.

- ^ "Religion: Youth for Christ". TIME. February 4, 1946. Retrieved November 22, 2022.

- ^ Carpenter 1999, pp. 184–5.

- ^ "Evangelicals and the World Council," Christianity Today, August 30, 1963, August 30, 1963, p. unknown, retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ Sweeney 2005, p. 199.

- ^ De Jong, Allison (May 10, 2018). "Protestants decline, more have no religion in a sharply shifting religious landscape (POLL) The nation's religious makeup has shifted dramatically in the past 15 years". ABC News. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick, David D (October 28, 2007). "The Evangelical Crackup". The New York Times Magazine.

- ^ "Edge Boss" (PDF). Akamai. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ Vu, Michelle A (July 29, 2008). "Rick Warren: Pastors Shouldn't Endorse Politicians". The Christian Post. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c Kurtzleben, Danielle (December 19, 2015). "Are You An Evangelical? Are You Sure?". NPR. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Olson 2008, p. 240.

- ^ "America's Changing Religious Landscape". Pew Research Center. May 12, 2015. Archived from the original on March 30, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ "The Unlikely Rebound of Mainline Protestantism". The New Yorker. July 16, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ "Survey: White mainline Protestants outnumber white evangelicals, while 'nones' shrink". Religion News Service. July 8, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ "About Three-in-Ten U.S. Adults Are Now Religiously Unaffiliated". Pew Research Center. December 14, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "Survey Explores Who Qualifies As an Evangelical". barna.com. The Barna Group. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ "Lift every voice". The Economist. May 5, 2012.

- ^ "The evangelical divide". The Economist. October 12, 2017.

- ^ How Many Evangelicals Are There?, Wheaton College: Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals, archived from the original on January 30, 2016, retrieved June 29, 2016

- ^ "Religion - Gallup Historical Trends". Gallup. 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Mathews 2017, p. iii.

- ^ "Political ideology among Evangelical Protestants - Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics".

- ^ Clark, Norman H (1976), Deliver Us from Evil: An Interpretation of American Prohibition.

- ^ "The Triumph of the Religious Right", The Economist November 11, 2004.

- ^ Himmelstein, Jerome L. (1990), To The Right: The Transformation of American Conservatism, University of California Press.

- ^ Martin, William (1996), With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America, New York: Broadway Books, ISBN 0-7679-2257-3.

- ^ Goldberg, Michelle. "Donald Trump, the Religious Right's Trojan Horse." New York Times. January 27, 2017. January 27, 2017.

- ^ Bean, Alan. "A thing that money could buy: How corporate evangelicalism elected a president" Baptist News Global. January 20, 2017. retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ Wehner, Peter. "The Evangelical Church is breaking apart: Christians must reclaim Jesus from his church." The Atlantic. October 24, 2021. retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Bean, Alan. "Understanding the evangelical civil war" Baptist News Global. November 8, 2021. retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Heineman, God is a Conservative, pp 71–2, 173

- ^ Swartz 2012, p. 7.

- ^ Shields, Jon A (2009), The Democratic Virtues of the Christian Right, pp. 117, 121.

- ^ Deckman, Melissa Marie (2004). School Board Battles: The Christian Right in Local Politics. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-58901-001-7. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

More than half of all Christian Right candidates attend evangelical Protestant churches that are more theologically liberal. A relatively large number of Christian Right candidates (24 percent) are Catholics; however, when asked to describe themselves as either "progressive/liberal" or "traditional/conservative" Catholics, 88 percent of these Christian Right candidates place themselves in the traditional category.

- ^ Joireman, Sandra F. (2009). "Anabaptism and the State: An Uneasy Coexistence". In Joireman, Sandra F. (ed.). Church, State, and Citizen: Christian Approaches to Political Engagement. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 73–91. ISBN 978-0-19-537845-0. LCCN 2008038533. S2CID 153268965. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ "Dr. Timothy Keller at the March 2013 Faith Angle Forum". Ethics & Public Policy Center. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ "Doctrine and Race: African American Evangelicals and Fundamentalism between the Wars". The Gospel Coalition. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Dreher, Rod (July 24, 2014). "What Is 'Traditional Christianity,' Anyway?". The American Conservative. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ "How U.S. religious composition has changed in recent decades". Pew Research Center. September 13, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Smith, Gregory A. (September 15, 2021). "More White Americans adopted than shed evangelical label during Trump presidency, especially his supporters". Pew Research Center. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ Burge, Ryan (October 26, 2021). "Opinion | Why 'Evangelical' Is Becoming Another Word for 'Republican'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ Noll 2001, pp. 154, 164.

- ^ Ten Major Court Cases about Evolution and Creationism. National Center for Science Education. 2001. ISBN 978-0-385-52526-8. Retrieved March 21, 2015..

- ^ Branch, Glenn (March 2007). "Understanding Creationism after Kitzmiller". BioScience. 57 (3): 278–284. doi:10.1641/B570313. ISSN 0006-3568. S2CID 86665329.

- ^ Kramer, Brad (August 8, 2018). "Famous Christians Who Believed Evolution is Compatible with Christian Faith". biologos.org. Archived from the original on January 6, 2020. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ Noll 2001, p. 163.

- ^ Numbers 2006, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Sullivan, Amy (May 2, 2009). "Helping Christians Reconcile God with Science". Time. Archived from the original on September 6, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ Collins 2006, p. 203.

- ^ Dudley, Jonathan (2011). Broken Words: The Abuse of Science and Faith in American Politics. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-385-52526-8. Retrieved February 24, 2015..

- ^ Heineman, Kenneth J. (1998). God is a Conservative: Religion, Politics and Morality in Contemporary America. pp. 44–123. ISBN 978-0-8147-3554-1.

- ^ Smith, Christian (2002). Christian America?: What Evangelicals Really Want. p. 207.

- ^ a b Rouse, Stella; Telhami, Shibley (September 21, 2022). "Most Republicans Support Declaring the United States a Christian Nation". Politico. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Nichols, John (September 23, 2022). "Republicans Are Ready to Declare the United States a Christian Nation". The Nation. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Smietana, Bob (September 23, 2022). "78% of Republican evangelicals want U.S. declared a Christian nation". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Root, Tik (March 9, 2016). "An Evangelical Movement Takes On Climate Change". Newsweek. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ Subramaniam, Meera (November 11, 2018). "Generation Climate: Can Young Evangelicals Change the Climate Debate?". InsideClimate News. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ Meyaard-Schaap, Kyle (September 29, 2020). "Young evangelicals are defying their elders' politics". CNN. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ Holcomb, Sarah (April 15, 2021). "Why Young Christians Are Pursuing Climate Action as an Urgent Calling". Christianity Today. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ Page, Erika (September 13, 2022). "Young Evangelicals seek to save the Earth – and their church". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ "Young Evangelicals for Climate Action". YECA. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Christian Evangelicals and U.S. Foreign Policy". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- ^ "Conceptualizing Evangelical Influence in U.S. Foreign Policy: Caught between Structural Realism and Neoliberal Institutionalism".

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (November 14, 2006). "For Evangelicals, Supporting Israel Is 'God's Foreign Policy'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

References

[edit]- Allis, Oswald T (1945). Prophecy and the Church. Philadelphia: Presbyterian & Reformed.

- Allitt, Patrick (2003). Religion in America Since 1945: A History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-2311-2154-7.

- Andrew, John A. III (1992). From Revivals to Removal: Jeremiah Evarts, the Cherokee Nation, and the Search for the Soul of America. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-1427-7.

- Balmer, Randall (1999). Blessed Assurance: A History of Evangelicalism in America. Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-7710-0.

- ——— (2002). Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22409-7..

- Bauder, Kevin (2011), "Fundamentalism", in Naselli, Andrew; Hansen, Collin (eds.), Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, ISBN 978-0-310-55581-0

- Bebbington, David W (1993), Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s, London: Routledge

- Carpenter, Joel A. (1999), Revive Us Again: The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-512907-5.

- Chartier, Myron Raymond (1969), The Social Views of Dwight L. Moody and Their Relation to the Workingman of 1860-1900. Fort Hays Studies Series. 40., Hays, Kansas: Fort Hays State University

- Collins, Francis S (2006). The Language of God: a Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-8639-1.

- Dayton, Donald W. (2001). The Variety of American Evangelicalism. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

- Dorrien, Gary J. (1998). The Remaking of Evangelical Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25803-0.

- Ellingsen, Mark (1991), "Lutheranism", in Dayton, Donald W.; Johnston, Robert K. (eds.), The Variety of American Evangelicalism, Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press, ISBN 1-57233-158-5

- Emerson, Michael O.; Smith, Christian (2001). Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-1951-4707-3.

- Finkelstein, Israel (2013). The Forgotten Kingdom: The Archaeology and History of Northern Israel (Ancient Near East Monographs). Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-5898-3912-0.

- FitzGerald, Frances (2017). The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-3133-6.

- Gloege, Timothy E.W. (2015). Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-3343-5.

- Grem, Darren E (2016). The Blessings of Business: How Corporations Shaped Conservative Christianity. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hannah-Jones, Nikole (2021). The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-5932-3057-2.

- Harden, Blaine (2021). Murder at the Mission. Viking.

- Himmelstein, Jerome L. (1990), To The Right: The Transformation of American Conservatism, University of California Press

- Hiett, Peter (2003). Eternity Now! Encountering the Jesus of Revelation. Nashville: Thomas Nelson.

- Hummel, Daniel G. (2023). The Rise and Fall of Dispensationalism: How the Evangelical Battle over the End Times Shaped a Nation. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-802-87922-6.

- Johnson, Paul E. (2004). A Shopkeeper's Millennium: Society and Revivals in Rochester, New York, 1815-1837. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 0-8090-1635-4.

- Johnson, Walter (2013). River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04555-2.

- Kidd, Thomas S. (2007). The Great Awakening: The Roots of Evangelical Christianity in Colonial America (Amazon Kindle). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11887-2.

- Lantzer, Jason S. (2012). Mainline Christianity: The Past and Future of America's Majority Faith. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5330-9.

- Longfield, Bradley J. (2013), Presbyterians and American Culture: A History, Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press

- Lovelace, Richard F (2007), The American Pietism of Cotton Mather: Origins of American Evangelicalism, Wipf & Stock, ISBN 978-1-55635-392-5

- Marsden, George M. (1991). Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0539-6.

- Marsden, George M. (2006). Fundamentalism and American Culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Martin, William (1996), With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America, New York: Broadway Books, ISBN 0-7679-2257-3

- Mathews, Mary Beth Swetnam (2017). Doctrine and Race: African American Evangelicals and Fundamentalism between the Wars. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-5918-8.

- McLoughlin, William G. (1980). Revivals, Awakenings, and Reform: An Essay on Religion and Social Change in America, 1607-1977. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Miller, Christopher L. (2003), Prophetic Worlds: Indians and Whites on the Columbia Plateau, Seattle: University of Washington Press

- Miller, Steven P. (2014). "Left, Right, Born Again". The Age of Evangelicalism: America's Born-Again Years. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 32–59. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199777952.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-977795-2. LCCN 2013037929. OCLC 881502753.

- Miller-Davenport, Sarah (2013). "'Their blood shall not be shed in vain': American Evangelical Missionaries and the Search for God and Country in Post–World War II Asia". Journal of American History. 99 (4): 1109–32. doi:10.1093/jahist/jas648. JSTOR 44307506.

- Mohler, Albert (2011), "Confessional Evangelicalism", in Naselli, Andrew; Hansen, Collin (eds.), Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, ISBN 978-0-310-55581-0

- Noll, Mark A. (1987). Between Faith and Criticism: Evangelicals, Scholarship and the Bible in America. HarperCollins.

- Noll, Mark A. (2001). American Evangelical Christianity: An Introduction. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-0-631-21999-6.

- ——— (2002). America's God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-803441-5.

- ——— (2003). The Rise of Evangelicalism: The Age of Edwards, Whitefield and the Wesleys. A History of Evangelicalism. Vol. 1. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 1-84474-001-3.

- Noll, Mark A. (2006). The Civil War As a Theological Crisis. University of North Carolina Press.

- Numbers, Ronald (November 30, 2006). The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design, Expanded Edition. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02339-0.

- Olson, David T. (2008). The American Church in Crisis. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

- Olson, Roger (2011), "Postconservative Evangelicalism", in Naselli, Andrew; Hansen, Collin (eds.), Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, ISBN 978-0-310-55581-0

- Pietsch, B. M. (2015). Dispensational Modernism. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1902-4408-8.

- Reimer, Sam (2003). Evangelicals and the Continental Divide: The Conservative Protestant Subculture in Canada and the United States. McGill-Queen's Press.

- Römer, Thomas; Geuss, Raymond (2015). The Invention of God. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-6745-0497-4.

- Sandeen, Ernest R (1970), The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800–1930, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Shantz, Douglas H (2013), An Introduction to German Pietism: Protestant Renewal at the Dawn of Modern Europe, JHU, ISBN 978-1-4214-0830-9

- Sivertsen, Barbara J. (2009). The Parting of the Sea: How Volcanoes, Earthquakes, and Plagues Shaped the Story of Exodus. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13770-4.

- Stanley, Brian (2013). The Global Diffusion of Evangelicalism: The Age of Billy Graham and John Stott. IVP Academic. ISBN 978-0-8308-2585-1.

- Steensland, Brian; Park, Jerry Z.; Regnerus, Mark D.; Robinson, Lynn D.; Wilcox, W. Bradford; Woodberry, Robert D. (September 2000). "The Measure of American Religion: Toward Improving the State of the Art". Social Forces. 79 (1). Oxford University Press: 291–318. doi:10.2307/2675572. JSTOR 2675572.

- Sutton, Matthew Avery. American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2014). 480 pp. online review

- Swartz, David R. (2012). Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-2306-4.

- Sweeney, Douglas A. (2005). The American Evangelical Story: A History of the Movement. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-58558-382-9.

- Tomlinson, Dave (2007). The Post-Evangelical. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-310-25385-3.

- Trueman, Carl (2011), The Real Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, Moody Publishers

- Vickers, Jason E. (2013). The Cambridge Companion to American Methodism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-43392-2.