Amazon (company)

| |

The Doppler building in Seattle, Amazon's headquarters | |

| Amazon | |

| Formerly | Cadabra, Inc. (1994–1995) |

| Company type | Public |

| ISIN | US0231351067 |

| Industry | |

| Founded | July 5, 1994, in Bellevue, Washington, U.S. |

| Founder | Jeff Bezos |

| Headquarters | Seattle, Washington and Arlington, Virginia , U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | |

| Products | |

| Services | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owner | Jeff Bezos (8.92%) |

Number of employees | ≈ 1,525,000 (2023) |

| Subsidiaries | List

|

| Website | amazon.com |

| Footnotes / references [1][2][3][4] | |

Amazon.com, Inc.,[1] doing business as Amazon (/ˈæməzɒn/, AM-ə-zon; UK also /ˈæməzən/, AM-ə-zən), is an American multinational technology company engaged in e-commerce, cloud computing, online advertising, digital streaming, and artificial intelligence.[5] Founded in 1994 by Jeff Bezos in Bellevue, Washington,[6] the company originally started as an online marketplace for books but gradually expanded its offerings to include a wide range of product categories, referred to as "The Everything Store".[7] Today, Amazon is considered one of the Big Five American technology companies, the other four being Alphabet,[a] Apple, Meta,[b] and Microsoft.

The company has multiple subsidiaries, including Amazon Web Services, providing cloud computing; Zoox, a self-driving car division; Kuiper Systems, a satellite Internet provider; and Amazon Lab126, a computer hardware R&D provider. Other subsidiaries include Ring, Twitch, IMDb, and Whole Foods Market. Its acquisition of Whole Foods in August 2017 for US$13.4 billion substantially increased its market share and presence as a physical retailer.[8] Amazon also distributes a variety of downloadable and streaming content through its Amazon Prime Video, MGM+, Amazon Music, Twitch, Audible and Wondery[9] units. It publishes books through its publishing arm, Amazon Publishing, film and television content through Amazon MGM Studios, including the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio, which was acquired in March 2022, and owns Brilliance Audio and Audible, which produce and distribute audiobooks, respectively. Amazon also produces consumer electronics—most notably, Kindle e-readers, Echo devices, Fire tablets, and Fire TVs.

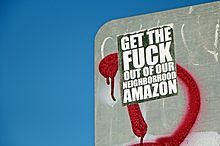

Amazon has a reputation as a disruptor of industries through technological innovation and aggressive reinvestment of profits into capital expenditures.[10][11][12][13] As of 2023[update], it is the world's largest online retailer and marketplace, smart speaker provider, cloud computing service through AWS,[14] live-streaming service through Twitch, and Internet company as measured by revenue and market share.[15] In 2021, it surpassed Walmart as the world's largest retailer outside of China, driven in large part by its paid subscription plan, Amazon Prime, which has close to 200 million subscribers worldwide.[16][17] It is the second-largest private employer in the United States[18] and the second-largest company in the World and in the U.S. by revenue as of 2024.[19] As of October 2024, Amazon is the 12th-most visited website in the world and 84% of its traffic comes from the United States.[20][21] Amazon is also the global leader in research and development spending, with R&D expenditure of US$73 billion in 2022.[22] Amazon has been criticized on various grounds, including but not limited to customer data collection practices, a toxic work culture, censorship, tax avoidance, and anti-competitive practices.

History

1994–2009

Amazon was founded on July 5, 1994, by Jeff Bezos after he relocated from New York City to Bellevue, Washington, near Seattle, to operate an online bookstore. Bezos chose the Seattle area for its abundance of technical talent from Microsoft and the University of Washington, as well as its smaller population for sales tax purposes and the proximity to a major book distribution warehouse in Roseburg, Oregon. Bezos also considered several other options, including Portland, Oregon, and Boulder, Colorado.[23] The company, originally named Cadabra, was founded in the converted garage of Bezos's house for symbolic reasons and was renamed to Amazon in November 1994.[24] The Amazon website launched for public sales on July 16, 1995, and initially sourced its books directly from wholesalers and publishers.[23][25]

Amazon went public in May 1997. It began selling music and videos in 1998, and began international operations by acquiring online sellers of books in the United Kingdom and Germany. In the subsequent year, it initiated the sale of a diverse range of products, including music, video games, consumer electronics, home improvement items, software, games, and toys.[26][27]

In 2002, it launched Amazon Web Services (AWS), which initially focused on providing APIs for web developers to build web applications on top of Amazon's ecommerce platform.[28][29] In 2004, AWS was expanded to provide website popularity statistics and web crawler data from the Alexa Web Information Service.[30] AWS later shifted toward providing enterprise services with Simple Storage Service (S3) in 2006,[31] and Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) in 2008,[32] allowing companies to rent data storage and computing power from Amazon. In 2006, Amazon also launched the Fulfillment by Amazon program, which allowed individuals and small companies (called "third-party sellers") to sell products through Amazon's warehouses and fulfillment infrastructure.[33]

2010–present

Amazon purchased the Whole Foods Market supermarket chain in 2017.[34] It is the leading e-retailer in the United States with approximately US$178 billion net sales in 2017. It has over 300 million active customer accounts globally.[35]

Amazon saw large growth during the COVID-19 pandemic, hiring more than 100,000 staff in the United States and Canada.[36] Some Amazon workers in the US, France, and Italy protested the company's decision to "run normal shifts" due to COVID-19's ease of spread in warehouses.[37][38] In Spain, the company faced legal complaints over its policies,[39] while a group of US Senators wrote an open letter to Bezos expressing concerns about workplace safety.[40]

On February 2, 2021, Bezos announced that he would step down as CEO to become executive chair of Amazon's board. The transition officially took place on July 5, 2021, with former CEO of AWS Andy Jassy replacing him as CEO.[41][42] In January 2023, Amazon cut over 18,000 jobs, primarily in consumer retail and its human resources division in an attempt to cut costs.[43]

On November 8, 2023, a plan was adopted for Jeff Bezos to sell approximately 50 million shares of the company over the next year (the deadline for the entire sales plan is January 31, 2025). The first step was the sale of 12 million shares for about $2 billion.[44]

On February 26, 2024, Amazon became a component of the Dow Jones Industrial Average.[45]

On December 19, 2024, Amazon workers, led by the International Brotherhood of Teamsters labor union, went on strike against Amazon in at least four US states, with workers in other facilities in the United States being welcomed to join the strike as well.[46][47]

Products and services

Amazon.com

Logo since January 2000 | |

Type of site | E-commerce |

|---|---|

| Available in |

|

| Owner | Amazon |

| URL | amazon |

| Commercial | Yes |

| Registration | Optional |

| Launched | 1995 |

| Current status | Active |

| Written in | C++ and Java |

| [48] | |

Amazon.com is an e-commerce platform that sells many product lines, including media (books, movies, music, and software), apparel, baby products, consumer electronics, beauty products, gourmet food, groceries, health and personal care products, industrial & scientific supplies, kitchen items, jewelry, watches, lawn and garden items, musical instruments, sporting goods, tools, automotive items, toys and games, and farm supplies[49] and consulting services.[50] Amazon websites are country-specific (for example, amazon.com for the US and amazon.co.uk for UK) though some offer international shipping.[51]

Visits to amazon.com grew from 615 million annual visitors in 2008,[52] to more than 2 billion per month in 2022.[citation needed] The e-commerce platform is the 12th most visited website in the world.[21]

In February 2024, Amazon announced its first chatbot was first “Rufus” in the US and in July, it was widely available to all customers in the US.[53]

“Rufus” is now available in the US, India and the UK which helps the shoppers get product recommendations, get shopping list advice, compare products and see what other customers have responded to their specific questions.[54]

Results generated by Amazon's search engine are partly determined by promotional fees.[55] The company's localized storefronts, which differ in selection and prices, are differentiated by top-level domain and country code:

| Country | share |

|---|---|

| United States | 69.3% |

| Germany | 6.5% |

| United Kingdom | 5.8% |

| Japan | 4.8% |

| Other | 13.6% |

| Region | Country | Domain name | Since | Languages | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | Egypt | amazon.eg | September 2021 | Arabic, English | Formerly known as Souq.com Egypt |

| South Africa | amazon.co.za | May 2024 | English | ||

| Americas | Brazil | amazon.com.br | December 2012 | Portuguese | |

| Canada | amazon.ca | June 2002 | English, French | ||

| Mexico | amazon.com.mx | August 2013 | Spanish | ||

| United States | amazon.com | July 1995 | English, Spanish, Arabic, German, Hebrew, Korean, Portuguese, Chinese (Simplified), Chinese (Traditional) | International customers without a localized Amazon website may purchase eBooks from the Kindle Store on Amazon US.[57] | |

| Asia | China | amazon.cn | September 2004 | Chinese (Simplified) | Formerly known as Joyo.com CHN |

| India | amazon.in | June 2013 | English, Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Bengali, Marathi | ||

| Japan | amazon.co.jp | November 2000 | Japanese, English, Chinese (Simplified) | ||

| Saudi Arabia | amazon.sa | June 2020 | Arabic, English | Formerly known as Souq.com KSA | |

| Singapore | amazon.sg | July 2017 | English | ||

| Turkey | amazon.com.tr | September 2018 | Turkish | ||

| United Arab Emirates | amazon.ae | May 2019 | Arabic, English | Formerly known as Souq.com UAE | |

| Europe | Belgium | amazon.com.be | October 2022 | Dutch, French, English | |

| France | amazon.fr | August 2000 | French, English | ||

| Germany | amazon.de | October 1998 | German, English, Czech, Dutch, Polish, Turkish | Also serves Austria,[58] Denmark[59] and Switzerland[60] | |

| Italy | amazon.it | November 2010 | Italian, English | ||

| Netherlands | amazon.nl | November 2014 | Dutch, English | Initially only books & e-books, full shop opened March 2020[61] | |

| Poland | amazon.pl | March 2021 | Polish | ||

| Spain | amazon.es | September 2011 | Spanish, Portuguese, English | Also serves Portugal[62] | |

| Sweden | amazon.se | October 2020 | Swedish, English | ||

| United Kingdom | amazon.co.uk | October 1998 | English | Also serves Ireland[63] | |

| Oceania | Australia | amazon.com.au | November 2017 | English | Also serves New Zealand[64] |

| Confirmed launch | |||||

| Europe | Ireland | amazon.ie | 2025[65] | English | Currently served by amazon.co.uk |

Merchant partnerships

In 2000, US toy retailer Toys "R" Us entered into a 10-year agreement with Amazon, valued at $50 million per year plus a cut of sales, under which Toys "R" Us would be the exclusive supplier of toys and baby products on the service, and the chain's website would redirect to Amazon's Toys & Games category. In 2004, Toys "R" Us sued Amazon, claiming that because of a perceived lack of variety in Toys "R" Us stock, Amazon had knowingly allowed third-party sellers to offer items on the service in categories that Toys "R" Us had been granted exclusivity. In 2006, a court ruled in favor of Toys "R" Us, giving it the right to unwind its agreement with Amazon and establish its independent e-commerce website. The company was later awarded $51 million in damages.[66][67][68]

In 2001, Amazon entered into a similar agreement with Borders Group, under which Amazon would comanage Borders.com as a co-branded service.[69] Borders pulled out of the arrangement in 2007, with plans to also launch its own online store.[70]

On October 18, 2011, Amazon.com announced a partnership with DC Comics for the exclusive digital rights to many popular comics, including Superman, Batman, Green Lantern, The Sandman, and Watchmen. The partnership has caused well-known bookstores like Barnes & Noble to remove these titles from their shelves.[71]

In November 2013, Amazon announced a partnership with the United States Postal Service to begin delivering orders on Sundays. The service, included in Amazon's standard shipping rates, initiated in metropolitan areas of Los Angeles and New York because of the high-volume and inability to deliver in a timely way, with plans to expand into Dallas, Houston, New Orleans and Phoenix by 2014.[72]

In June 2017, Nike agreed to sell products through Amazon in exchange for better policing of counterfeit goods.[73][74] This proved unsuccessful and Nike withdrew from the partnership in November 2019.[74][75] Companies including IKEA and Birkenstock also stopped selling through Amazon around the same time, citing similar frustrations over business practices and counterfeit goods.[76]

In September 2017, Amazon ventured with one of its sellers JV Appario Retail owned by Patni Group which has recorded a total income of US$ 104.44 million (₹759 crore) in financial year 2017–2018.[77]

As of October 11, 2017[update], AmazonFresh sold a range of Booths branded products for home delivery in selected areas.[78]

In November 2018, Amazon reached an agreement with Apple Inc. to sell selected products through the service, via the company and selected Apple Authorized Resellers. As a result of this partnership, only Apple Authorized Resellers may sell Apple products on Amazon effective January 4, 2019.[79][80]

On November 7, 2024, Amazon is reportedly discussing a second multi-billion dollar investment in AI startup Anthropic, following its initial $4 billion investment.[81]

Private-label products

Amazon sells many products under its own brand names, including phone chargers, batteries, and diaper wipes. The AmazonBasics brand was introduced in 2009, and now features hundreds of product lines, including smartphone cases, computer mice, batteries, dumbbells, and dog crates. Amazon owned 34 private-label brands as of 2019. These brands account for 0.15% of Amazon's global sales, whereas the average for other large retailers is 18%.[82] Other Amazon retail brands include Presto!, Mama Bear, and Amazon Essentials.[83]

-

Amazon Basics stapler

-

Amazon Basics USB cable

-

Amazon Basics battery

-

Amazon Basics disinfecting wipes

Third-party sellers

Amazon derives many of its sales (around 40% in 2008) from third-party sellers who sell products on Amazon.[84] Some other large e-commerce sellers use Amazon to sell their products in addition to selling them through their websites. The sales are processed through Amazon.com and end up at individual sellers for processing and order fulfillment and Amazon leases space for these retailers. Small sellers of used and new goods go to Amazon Marketplace to offer goods at a fixed price.[85]

Affiliate program

Publishers can sign up as affiliates and receive a commission for referring customers to Amazon by placing links to Amazon on their websites if the referral results in a sale. Worldwide, Amazon has "over 900,000 members" in its affiliate programs.[86] In the middle of 2014, the Amazon Affiliate Program is used by 1.2% of all websites and it is the second most popular advertising network after Google Ads.[87] It is frequently used by websites and non-profits to provide a way for supporters to earn them a commission.[88]

Associates can access the Amazon catalog directly on their websites by using the Amazon Web Services (AWS) XML service. A new affiliate product, aStore, allows Associates to embed a subset of Amazon products within another website, or linked to another website. In June 2010, Amazon Seller Product Suggestions was launched to provide more transparency to sellers by recommending specific products to third-party sellers to sell on Amazon. Products suggested are based on customers' browsing history.[89]

Product reviews

Amazon allows users to submit reviews to the web page of each product. Reviewers must rate the product on a rating scale from one to five stars. Amazon provides a badging option for reviewers which indicates the real name of the reviewer (based on confirmation of a credit card account) or which indicates that the reviewer is one of the top reviewers by popularity. As of December 16, 2020, Amazon removed the ability of sellers and customers to comment on product reviews and purged their websites of all posted product review comments. In an email to sellers, Amazon gave its rationale for removing this feature: "...the comments feature on customer reviews was rarely used." The remaining review response options are to indicate whether the reader finds the review helpful or to report that it violates Amazon policies (abuse). If a review is given enough "helpful" hits, it appears on the front page of the product. In 2010, Amazon was reported as being the largest single source of Internet consumer reviews.[90]

When publishers asked Bezos why Amazon would publish negative reviews, he defended the practice by claiming that Amazon.com was "taking a different approach...we want to make every book available—the good, the bad and the ugly...to let truth loose".[91]

There have been cases of positive reviews being written and posted by public relations companies on behalf of their clients[92] and instances of writers using pseudonyms to leave negative reviews of their rivals' works.

Amazon sales rank

The Amazon sales rank (ASR) indicates the popularity of a product sold on any Amazon locale. It is a relative indicator of popularity that is updated hourly. Effectively, it is a "best sellers list" for the millions of products stocked by Amazon.[93] While the ASR has no direct effect on the sales of a product, it is used by Amazon to determine which products to include in its bestsellers lists.[93] Products that appear in these lists enjoy additional exposure on the Amazon website and this may lead to an increase in sales. In particular, products that experience large jumps (up or down) in their sales ranks may be included within Amazon's lists of "movers and shakers"; such a listing provides additional exposure that might lead to an increase in sales.[94] For competitive reasons, Amazon does not release actual sales figures to the public. However, Amazon has now begun to release point of sale data via the Nielsen BookScan service to verified authors.[95] While the ASR has been the source of much speculation by publishers, manufacturers, and marketers, Amazon itself does not release the details of its sales rank calculation algorithm. Some companies have analyzed Amazon sales data to generate sales estimates based on the ASR,[96] though Amazon states:

Please keep in mind that our sales rank figures are simply meant to be a guide of general interest for the customer and not definitive sales information for publishers—we assume you have this information regularly from your distribution sources

— Amazon.com Help[97]

Physical stores

In November 2015, Amazon opened a physical Amazon Books store in University Village in Seattle. The store was 5,500 square feet and prices for all products matched those on its website.[98] Amazon opened its tenth physical bookstore in 2017;[99] media speculation at the time suggested that Amazon planned to eventually roll out 300 to 400 bookstores around the country.[98] All of its locations were closed in 2022 along with other retail locations under the "Amazon 4-Star" brand.[100]

In July 2016, the company announced that it was opening a 1,100,000 ft (335,280.0 m) square foot facility in Palmer Township in the Lehigh Valley region of eastern Pennsylvania. As of 2024, Amazon is Lehigh Valley region's third-largest employer.[101][102]

In August 2019, Amazon applied to have a liquor store in San Francisco, as a means to ship beer and alcohol within the city.[103]

In 2020, Amazon Fresh opened several physical stores in the US and the United Kingdom.[104]

Hardware and services

Amazon has a number of products and services available, including its digital assistant Alexa, Amazon Music, and Prime Video for music and videos respectively, the Amazon Appstore for Android apps, the Kindle line of eink e-readers, Fire and Fire HD color LCD tablets. Audible provides audiobooks for purchase and listening.

In September 2021, Amazon announced the launch of Astro, its first household robot, powered by its Alexa smart home technology. This can be remote-controlled when not at home, to check on pets, people, or home security. It will send owners a notification if it detects something unusual.[105]

In January 2023, Amazon announced the launch of RXPass, a prescription drug delivery service. It allows U.S. Amazon Prime members to pay a $5 monthly fee for access to 60 medications. The service was launched immediately after the announcement except in states with specific prescription delivery requirements. Beneficiaries of government healthcare programs such as Medicare and Medicaid will not be able to sign up for RXPass.[106]

Subsidiaries

Amazon owns over 100 subsidiaries, including Amazon Web Services, Audible, Diapers.com, Goodreads, IMDb, Kiva Systems (now Amazon Robotics), One Medical, Shopbop, Teachstreet, Twitch, Zappos, and Zoox.[107]

Bezos separately owns The Washington Post (through Nash Holdings, LLC), Blue Origin, Bezos Expeditions, Altos Labs, and other companies.

Amazon Live

| |

Type of site | Online video platform |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | 98109, WA Seattle, Washington, United States |

| Owner | Amazon Inc. |

| Industry |

|

| Parent | Amazon Inc. |

| Launched | 2019 |

Amazon Live is an American video e-commerce live-streaming service created by Amazon Inc. to compete with live-streaming services. The service allows users to stream live videos promoting or sponsoring products.[108] Users (mainly celebrities or Internet influencers) have the option to livestream on Amazon and add tags to additionally add context to the products they're selling or promoting. Other users can join in and type in messages to send to a global chat on the livestream.[108]

In 2019 Amazon launched an integrated platform into the Amazon website and application. In 2023 roughly a billion total viewers watch Amazon Live across the United States and India. The platform has also been integrated into Amazon Freevee and Amazon Prime Video.[109]

Amazon Web Services

Amazon Web Services (AWS) is a subsidiary of Amazon that provides on-demand cloud computing platforms and APIs to individuals, companies, and governments, on a metered pay-as-you-go basis. These cloud computing web services provide distributed computing processing capacity and software tools via AWS server farms. As of 2021 Q4, AWS has 33% market share for cloud infrastructure while the next two competitors Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud have 21%, and 10% respectively, according to Synergy Group.[110]

Audible

Audible is a seller and producer of spoken audio entertainment, information, and educational programming on the Internet. Audible sells digital audiobooks, radio and television programs, and audio versions of magazines and newspapers. Through its production arm, Audible Studios, Audible has also become the world's largest producer of downloadable audiobooks. On January 31, 2008, Amazon announced it would buy Audible for about $300 million. The deal closed in March 2008 and Audible became a subsidiary of Amazon.[111]

Goodreads

Goodreads is a "social cataloging" website founded in December 2006 and launched in January 2007 by Otis Chandler, a software engineer, and entrepreneur, and Elizabeth Khuri. The website allows individuals to freely search Goodreads' extensive user-populated database of books, annotations, and reviews. Users can sign up and register books to generate library catalogs and reading lists. They can also create their groups of book suggestions and discussions. In December 2007, the site had over 650,000 members, and over a million books had been added. Amazon bought the company in March 2013.[112]

Ring

Ring is a home automation company founded by Jamie Siminoff in 2013. It is primarily known for its WiFi powered smart doorbells, but manufactures other devices such as security cameras. Amazon bought Ring for US$1 billion in 2018.[113]

Twitch

Twitch is a live streaming platform for video, primarily oriented towards video gaming content. Twitch was acquired by Amazon in August 2014 for $970 million.[114] The site's rapid growth had been boosted primarily by the prominence of major esports competitions on the service, leading GameSpot senior esports editor Rod Breslau to have described the service as "the ESPN of esports".[115] As of 2015[update], the service had over 1.5 million broadcasters and 100 million monthly viewers.[116]

Whole Foods Market

Whole Foods Market is an American supermarket chain exclusively featuring foods without artificial preservatives, colors, flavors, sweeteners, and hydrogenated fats.[117] Amazon acquired Whole Foods for $13.7 billion in August 2017.[118][119][8]

Other

Other Amazon subsidiaries include:

- A9.com, a company focused on researching and building innovative technology; it has been a subsidiary since 2003.[120]

- Amazon Academy, formerly JEE Ready, is an online learning platform for engineering students to prepare for competitive exams like the Joint Entrance Examination (JEE), launched by Amazon India on 13 January 2021

- Amazon Maritime, Inc. holds a Federal Maritime Commission license to operate as a non-vessel-owning common carrier (NVOCC), which enables the company to manage its shipments from China into the United States.[121]

- Amazon Pharmacy is an online delivery service dedicated to prescription drugs, launched in November 2020. The service provides discounts up to 80% for generic drugs and up to 40% for branded drugs for Prime subscribe users. The products can be purchased on the company's website or at over 50,000 bricks-and-mortar pharmacies in the United States.[122]

- Annapurna Labs, an Israel-based microelectronics company reputedly for US$350–370M acquired by Amazon Web Services in January 2015 .[123][124][125]

- Beijing Century Joyo Courier Services, which applied for a freight forwarding license with the US Maritime Commission. Amazon is also building out its logistics in trucking and air freight to potentially compete with UPS and FedEx.[126][127]

- Brilliance Audio, an audiobook publisher founded in 1984 by Michael Snodgrass in Grand Haven, Michigan.[128] The company produced its first eight audio titles in 1985.[128] The company was purchased by Amazon in 2007 for an undisclosed amount.[129][130] At the time of the acquisition, Brilliance was producing 12–15 new titles a month.[130] It operates as an independent company within Amazon. In 1984, Brilliance Audio invented a technique for recording twice as much on the same cassette.[131] The technique involved recording on each of the two channels of each stereo track.[131] It has been credited with revolutionizing the burgeoning audiobook market in the mid-1980s since it made unabridged books affordable.[131]

- ComiXology, a cloud-based digital comics platform with over 200 million comic downloads as of September 2013[update]. It offers a selection of more than 40,000 comic books and graphic novels across Android, iOS, Fire OS and Windows 8 devices and over a web browser. Amazon bought the company in April 2014.[132]

- CreateSpace, which offers self-publishing services for independent content creators, publishers, film studios, and music labels, became a subsidiary in 2009.[133][134]

- Eero, an electronics company specializing in mesh-networking Wifi devices founded as a startup in 2014 by Nick Weaver, Amos Schallich, and Nate Hardison to simplify and innovate the smart home.[135] Eero was acquired by Amazon in 2019 for US$97 million.[136] Eero has continued to operate under its banner and advertises its commitment to privacy despite early concerns from the company's acquisition.[137]

- Health Navigator is a startup developing APIs for online health services acquired in October 2019. The startup will form part of Amazon Care, which is the company's employee healthcare service. This follows the 2018 purchase of PillPack for under $1 billion, which has also been included into Amazon Care.[138]

- Junglee, a former online shopping service provided by Amazon that enabled customers to search for products from online and offline retailers in India. Junglee started as a virtual database that was used to extract information from the Internet and deliver it to enterprise applications. As it progressed, Junglee started to use its database technology to create a single window marketplace on the Internet by making every item from every supplier available for purchase. Web shoppers could locate, compare and transact millions of products from across the Internet shopping mall through one window.[139] Amazon acquired Junglee in 1998, and the website Junglee.com was launched in India in February 2012[140] as a comparison-shopping website. It curated and enabled searching for a diverse variety of products such as clothing, electronics, toys, jewelry, and video games, among others, across thousands of online and offline sellers. Millions of products are browsable, the client selects a price, and then they are directed to a seller. In November 2017, Amazon closed down Junglee.com and the former domain currently redirects to Amazon India.[141]

- Kuiper Systems, a subsidiary of Amazon, set up to deploy a broadband satellite internet constellation with an announced 3,236 Low Earth orbit satellites to provide satellite based Internet connectivity.[142][143][144]

- Lab126, developers of integrated consumer electronics such as the Kindle, became a subsidiary in 2004.[145]

- Shelfari, a former social cataloging website for books. Shelfari users built virtual bookshelves of the titles which they owned or had read and they could rate, review, tag and discuss their books. Users could also create groups that other members could join, create discussions and talk about books, or other topics. Recommendations could be sent to friends on the site for what books to read. Amazon bought the company in August 2008.[112] Shelfari continued to function as an independent book social network within the Amazon until January 2016, when Amazon announced that it would be merging Shelfari with Goodreads and closing down Shelfari.[146][147]

- Souq, the former largest e-commerce platform in the Arab world. The company launched in 2005 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates and served multiple areas across the Middle East.[148] On March 28, 2017, Amazon acquired Souq.com for $580 million.[149] The company was re-branded as Amazon and its infrastructure was used to expand Amazon's online platform in the Middle East.[150]

Amazon also has investments in renewable energy, including plans to fund four modular nuclear reactors at the Xe-100 reactor site in Eastern Washington, and plans to expand its position into the Canadian market through an investment in a new plant in Alberta.[151]

Operations

Logistics

Amazon uses many different transportation services to deliver packages. Amazon-branded services include:

- Amazon Air, a cargo airline for bulk transport, with last-mile delivery handled either by Amazon Flex, Amazon Logistics, or the U.S. Postal Service.

- Amazon Flex, a smartphone app that enables individuals to act as independent contractors, delivering packages to customers from personal vehicles without uniforms. Deliveries include one or two hours Prime Now, same or next day Amazon Fresh groceries, and standard Amazon.com orders, in addition to orders from local stores that contract with Amazon.[152]

- Amazon Logistics, in which Amazon contracts with small businesses (which it calls "Delivery Service Partners") to perform deliveries to customers. Each business has a fleet of approximately 20–40 Amazon-branded vans, and employees of the contractors wear Amazon uniforms. As of December 2020, it operates in the United States, Canada, Italy, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom.[153]

- Amazon Prime Air is an experimental drone delivery service that delivers packages via drones to Amazon Prime subscribers in select cities.

Amazon directly employs people to work at its warehouses, bulk distribution centers, staffed "Amazon Hub Locker+" locations, and delivery stations where drivers pick up packages. As of December 2020, it is not hiring delivery drivers as employees.[154]

Rakuten Intelligence estimated that in 2020 in the United States, the proportion of last-mile deliveries was 56% by Amazon's directly contracted services (mostly in urban areas), 30% by the US Postal Service (mostly in rural areas), and 14% by UPS.[155] In April 2021, Amazon reported to investors it had increased its in-house delivery capacity by 50% in the last 12 months (which included the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States).[156]

Supply chain

Amazon first launched its distribution network in 1997 with two fulfillment centers in Seattle and New Castle, Delaware. Amazon has several types of distribution facilities consisting of cross-dock centers, fulfillment centers, sortation centers, delivery stations, Prime now hubs, and Prime air hubs. There are 75 fulfillment centers and 25 sortation centers with over 125,000 employees.[157][158] Employees are responsible for five basic tasks: unpacking and inspecting incoming goods; placing goods in storage and recording their location; picking goods from their computer recorded locations to make up an individual shipment; sorting and packing orders; and shipping. A computer that records the location of goods and maps out routes for pickers plays a key role: employees carry hand-held computers which communicate with the central computer and monitor their rate of progress. Some warehouses are partially automated with systems built by Amazon Robotics.[159]

In September 2006, Amazon launched a program called FBA (Fulfillment By Amazon) whereby it could handle storage, packing and distribution of products and services for small sellers.[33]

-

Amazon.fr fulfillment center in Lauwin-Planque, France

-

Amazon.es fulfillment center in San Fernando de Henares, Spain

Corporate affairs

Board of directors

As of June 2022[update], Amazon's board of directors were:[160]

- Jeff Bezos, executive chairman, Amazon.com, Inc.

- Andy Jassy, president and CEO, Amazon.com, Inc.

- Keith B. Alexander, CEO of IronNet Cybersecurity, former NSA director

- Edith W. Cooper, co-founder of Medley and former EVP of Goldman Sachs

- Jamie Gorelick, partner, Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr

- Daniel P. Huttenlocher, dean of the Schwarzman College of Computing, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Judy McGrath, former CEO, MTV Networks

- Indra Nooyi, former CEO, PepsiCo

- Jon Rubinstein, former chairman and CEO, Palm, Inc.

- Patty Stonesifer, president and CEO, Martha's Table

- Wendell P. Weeks, chairman, president and CEO, Corning Inc.

Ownership

The 10 largest shareholder of Amazon in early 2024 were:[56]

| Shareholder name | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Jeff Bezos | 9.1% |

| The Vanguard Group | 7.5% |

| BlackRock | 4.6% |

| State Street Corporation | 3.3% |

| Fidelity Investments | 3.1% |

| MacKenzie Scott | 1.9% |

| T. Rowe Price | 1.9% |

| Geode Capital Management | 1.8% |

| JP Morgan Investment Management | 1.5% |

| Eaton Vance | 1.5% |

| Others | 63.8% |

Finances

| Business | share |

|---|---|

| Online Stores | 40.3% |

| Third-party Seller Services | 24.4% |

| Amazon Web Services | 15.8% |

| Advertising | 8.2% |

| Subscription Services | 7.0% |

| Physical Stores | 3.5% |

| Other | 0.9% |

Amazon.com is primarily a retail site with a sales revenue model; Amazon takes a small percentage of the sale price of each item that is sold through its website while also allowing companies to advertise their products by paying to be listed as featured products.[161] As of 2018[update], Amazon.com is ranked eighth on the Fortune 500 rankings of the largest United States corporations by total revenue.[162] In Forbes Global 2000 2023 Amazon ranked 36th.[163]

For the fiscal year 2021, Amazon reported earnings of US$33.36 billion, with an annual revenue of US$469.82 billion, an increase of 21.7% over the previous fiscal cycle. Since 2007 sales increased from 14.835 billion to 469.822 billion, due to continued business expansion.[citation needed]

Amazon's market capitalization went over US$1 trillion again in early February 2020 after the announcement of the fourth quarter 2019 results.[164]

| Year | Revenue[165] in million US$ |

Net income in million US$ |

Total Assets in million US$ |

Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995[166] | 0.5 | −0.3 | 1.1 | |

| 1996[166] | 16 | −6 | 8 | |

| 1997[166] | 148 | −28 | 149 | 614 |

| 1998[167] | 610 | −124 | 648 | 2,100 |

| 1999[167] | 1,639 | −720 | 2,466 | 7,600 |

| 2000[167] | 2,761 | −1,411 | 2,135 | 9,000 |

| 2001[167] | 3,122 | −567 | 1,638 | 7,800 |

| 2002[167] | 3,932 | −149 | 1,990 | 7,500 |

| 2003[168] | 5,263 | 35 | 2,162 | 7,800 |

| 2004[168] | 6,921 | 588 | 3,248 | 9,000 |

| 2005[168] | 8,490 | 359 | 3,696 | 12,000 |

| 2006[168] | 10,711 | 190 | 4,363 | 13,900 |

| 2007[168] | 14,835 | 476 | 6,485 | 17,000 |

| 2008[169] | 19,166 | 645 | 8,314 | 20,700 |

| 2009[170] | 24,509 | 902 | 13,813 | 24,300 |

| 2010[171] | 34,204 | 1,152 | 18,797 | 33,700 |

| 2011[172] | 48,077 | 631 | 25,278 | 56,200 |

| 2012[173] | 61,093 | −39 | 32,555 | 88,400 |

| 2013[174] | 74,452 | 274 | 40,159 | 117,300 |

| 2014[175] | 88,988 | −241 | 54,505 | 154,100 |

| 2015[176] | 107,006 | 596 | 64,747 | 230,800 |

| 2016[177] | 135,987 | 2,371 | 83,402 | 341,400 |

| 2017[178] | 177,866 | 3,033 | 131,310 | 566,000 |

| 2018[179] | 232,887 | 10,073 | 162,648 | 647,500 |

| 2019[180] | 280,522 | 11,588 | 225,248 | 798,000 |

| 2020[181] | 386,064 | 21,331 | 321,195 | 1,298,000 |

| 2021[182] | 469,822 | 33,364 | 420,549 | 1,608,000 |

| 2022[182] | 513,983 | −2,722 | 462,675 | 1,541,000 |

| 2023[1] | 574,785 | 30,425 | 527,854 | 1,525,000 |

Corporate culture

During his tenure, Jeff Bezos had become renowned for his annual shareholder letters, which have gained similar notability to those of Warren Buffett.[183] These annual letters gave an "invaluable window" into the famously "secretive" company, and revealed Bezos's perspectives and strategic focus.[183][184] A common theme of these letters is Bezos's desire to instill customer-centricity (in his words, "customer obsession") at all levels of Amazon, notably by making all senior executives field customer support queries for a short time at Amazon call centers. He also read many emails addressed by customers to his public email address.[185] One of Bezos's most well-known internal memos was his mandate for "all teams" to "expose their data and functionality" through service interfaces "designed from the ground up to be externalizable". This process, commonly known as a service-oriented architecture (SOA), resulted in mandatory dogfooding of services that would later be commercialized as part of AWS.[citation needed]

Lobbying

Amazon lobbies the United States federal government and state governments on multiple issues such as the enforcement of sales taxes on online sales, transportation safety, privacy and data protection and intellectual property. According to regulatory filings, Amazon.com focuses its lobbying on the United States Congress, the Federal Communications Commission and the Federal Reserve. Amazon.com spent roughly $3.5 million, $5 million and $9.5 million on lobbying, in 2013, 2014 and 2015, respectively.[186] In 2019, it spent $16.8 million and had a team of 104 lobbyists.[187]

Amazon.com was a corporate member of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) until it dropped membership following protests at its shareholders' meeting on May 24, 2012.[188]

In 2014, Amazon expanded its lobbying practices as it prepared to lobby the Federal Aviation Administration to approve its drone delivery program, hiring the Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld lobbying firm in June.[189] Amazon and its lobbyists have visited with Federal Aviation Administration officials and aviation committees in Washington, D.C. to explain its plans to deliver packages.[190] In September 2020 this moved one step closer with the granting of a critical certificate by the FAA.[191]

Criticism

Amazon has attracted criticism for its actions, including: supplying law enforcement with facial recognition surveillance tools;[192] forming cloud computing partnerships with the CIA;[193] leading customers away from bookshops;[194] adversely impacting the environment;[195] placing a low priority on warehouse conditions for workers;[196][197] actively opposing unionization efforts;[198] remotely deleting content purchased by Amazon Kindle users; taking public subsidies; seeking to patent its 1-Click technology; engaging in anti-competitive actions and price discrimination;[199][200] and reclassifying LGBT books as adult content.[201][202] Criticism has also concerned various decisions over whether to censor or publish content such as the WikiLeaks website, works containing libel, anti-LGBT merchandise, and material facilitating dogfight, cockfight, or pedophile activities. An article published by Time in the wake of social media website Parler's termination of service by Amazon Web Service highlights the power companies like Amazon now have over the internet.[203] In December 2011, Amazon faced a backlash from small businesses for running a one-day deal to promote its new Price Check app. Shoppers who used the app to check prices in a brick-and-mortar store were offered a 5% discount to purchase the same item from Amazon.[204] Companies like Groupon, eBay and Taap have countered Amazon's promotion by offering $10 off from their products.[205][206]

The company has also faced accusations of putting undue pressure on suppliers to maintain and extend its profitability. One effort to squeeze the most vulnerable book publishers was known within the company as the Gazelle Project, after Bezos suggested, according to Brad Stone, "that Amazon should approach these small publishers the way a cheetah would pursue a sickly gazelle."[55] In July 2014, the Federal Trade Commission launched a lawsuit against the company alleging it was promoting in-app purchases to children, which were being transacted without parental consent.[207] In 2019, Amazon banned selling skin-lightening products after pushback from Minnesota health and environmental activists.[208] In 2022, a lawsuit filed by state attorney-general Letitia James was dismissed by the New York state court of appeals.[209] After the COVID-19 pandemic, Amazon faced criticism for complying, under pressure from the Biden Administration, to "reduce the visibility” of books critical of the COVID-19 vaccine,[210][211] which was revealed after Rep. Jim Jordan (acting on behalf of the House Judiciary Committee) subpoenaed emails between the company and the Biden Administration.[212]

Amazon Prime has been criticized for its vehicles systemically double parking, blocking bike lanes, and otherwise violating traffic laws while dropping off packages, contributing to traffic congestion and endangering other road users.[213][214][215][216]

Jane Friedman[217] discovered six listings of books fraudulently using her name, on Amazon and Goodreads. Amazon and Goodreads resisted removing the fraudulent titles until the author's complaints went viral on social media, in a blog post titled "I Would Rather See My Books Get Pirated Than This (Or: Why Goodreads and Amazon Are Becoming Dumpster Fires)."[218][219][220][221]

In 2024, following years of criticism for providing law enforcement footage in the custody of Ring (a home security company owned by Amazon) without a warrant, Ring has halted this practice.[222] It received cautious praise from privacy-focused organizations such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation for this change.[222]

See also

- Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award

- Amazon Pay

- Amazon Standard Identification Number (ASIN)

- Amazon Storywriter

- Camelcamelcamel – a website that tracks the prices of products sold on Amazon.com

- History of Amazon

- Internal carbon pricing

- List of book distributors

- Statistically improbable phrases – Amazon.com's phrase extraction technique for indexing books

References

- ^ a b c "Amazon.com, Inc. 2023 Form 10-K Annual Report". US Securities and Exchange Commission. February 2, 2024. Archived from the original on February 3, 2024. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ "California Secretary of State Business Search". Secretary of State of California. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ "Amazon.com, Inc. 2022 Proxy Statement". US Securities and Exchange Commission. April 14, 2022. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ Reuter, Dominick (July 30, 2021). "1 out of every 153 American workers is an Amazon employee". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 3, 2022. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon Empire: The Rise and Reign of Jeff Bezos". PBS. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Guevara, Natalie (November 17, 2020). "Amazon's John Schoettler has helped change how we think of corporate campuses". Puget Sound Business Journal. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko (October 28, 2013). "Selling as Hard as He Can". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Amazon and Whole Foods Market Announce Acquisition to Close This Monday, Will Work Together to Make High-Quality, Natural and Organic Food Affordable for Everyone" (Press release). Business Wire. August 24, 2017. Archived from the original on September 13, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ Carman, Ashley (December 30, 2020). "Amazon buys Wondery, setting itself up to compete against Spotify for podcast domination". The Verge. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ Furth, John F. (May 18, 2018). "Why Amazon and Jeff Bezos Are So Successful at Disruption". Entrepreneur. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ Bylund, Per (August 29, 2017). "Amazon's Lesson About Disruption: Rattle Any Market You Can". Entrepreneur. Archived from the original on March 28, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ "How to compete with Amazon". Fortune. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "Reinvesting for Growth – Why Amazon.com, Inc. (NASDAQ:AMZN) is Undervalued Even in this Market". Yahoo Finance. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "Microsoft Cloud Revenues Leap; Amazon is Still Way Out in Front". Reno, Nevada: Synergy Research Group. October 29, 2014. Archived from the original on May 4, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ Jopson, Barney (July 12, 2011). "Amazon urges California referendum on online tax". Financial Times. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- ^ "Amazon Prime now has 200 million members, jumping 50 million in one year". Yahoo News. April 15, 2021. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Spangler, Todd (April 15, 2021). "Amazon Prime Tops 200 Million Members, Jeff Bezos Says". Variety. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ Cheng, Evelyn (September 23, 2016). "Amazon climbs into list of top five largest US stocks by market cap". CNBC. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ "Fortune Global 500". Fortune. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ "Top Websites Ranking". Similarweb. Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ a b "amazon.com". similarweb.com. Archived from the original on October 24, 2022. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Intelligence, fDi. "Top 100 global innovation leaders". www.fdiintelligence.com. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Romano, Benjamin (June 29, 2019). "Amazon at 25: The magic that changed everything". The Seattle Times. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Spector, Robert (April 16, 2000). "Homegrown Amazon". The Seattle Times. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Perez, Elizabeth (June 28, 2019). "Store on internet is open book — Amazon.com boasts more than 1 million titles on web". The Seattle Times. p. E1. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Anders, George; Tessler, Joelle (June 8, 1999). "Amazon.com Steps Into World Of Online, Downloadable Music". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Anders, George (July 13, 1999). "Amazon.com Unveils Plans to Open Two More 'Stores' on Its Web Site". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon.com Launches Web Services; Developers Can Now Incorporate Amazon.com Content and Features into Their Own Web Sites; Extends Welcome Mat for Developers" (Press release). Amazon.com Press Center. July 16, 2002. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon.com Web Services Announces Trio of Milestones - New Tool Kit, Enhanced Web Site and 25,000 Developers in the Program" (Press release). Amazon.com Press Center. March 19, 2003. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "New Amazon Web Services Offerings Give Developers Unprecedented Access to Amazon Product Data and Technology, and First-Ever Access to Data Compiled by Alexa Internet" (Press release). Amazon.com Press Center. October 4, 2004. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon Web Services Launches" (Press release). Amazon.com Press Center. March 14, 2006. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon Web Services Launches Amazon EC2 for Windows" (Press release). Amazon.com Press Center. October 23, 2008. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

Additionally, AWS today announced that Amazon EC2 is now Generally Available, having successfully exited its beta period and now offers a Service Level Agreement (SLA)

- ^ a b "Amazon Launches New Services to Help Small and Medium-Sized Businesses Enhance Their Customer Offerings by Accessing Amazon's Order Fulfillment, Customer Service, and Website Functionality" (Press release). Amazon.com Press Center. September 19, 2006. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon.com - History & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Schmidt, Gordon B. (2020), "Amazon", The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Mass Media and Society, Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc., doi:10.4135/9781483375519.n28, ISBN 978-1-4833-7551-9, S2CID 240656642, retrieved May 1, 2023

- ^ Otto, Ben (September 14, 2020). "Amazon to Hire 100,000 in US and Canada". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 13, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- ^ "Amazon hiring spree as orders surge under lockdown". BBC News. April 14, 2020. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ "Amazon workers protest over normal shifts despite Covid-19 cases". Financial Times. March 19, 2020. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- ^ "Amazon workers strike over virus protection". BBC News. March 31, 2020. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ Dzieza, Josh (March 30, 2020). "Amazon warehouse workers walk out in rising tide of COVID-19 protests". The Verge. Archived from the original on July 12, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ "Amazon founder Jeff Bezos will step down as CEO". Fox8. Associated Press. February 2, 2021. Archived from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Haselton, Todd (February 2, 2021). "Jeff Bezos to step down as Amazon CEO, Andy Jassy to take over in Q3". CNBC. Archived from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ "Amazon to shed over 18,000 jobs as it cuts costs, CEO says". BBC News. January 5, 2023. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "Jeff Bezos sells roughly $2 billion of Amazon shares". The Economic Times. February 11, 2024. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ "Amazon Set to Join Dow Jones Industrial Average and Uber to Join Dow Jones Transportation Average" (PDF) (Press release). S&P Dow Jones Indices. February 20, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ "Teamsters Launch Strike Against Amazon In American". International Brotherhood of Teamsters. December 19, 2024. Retrieved December 19, 2024.

- ^ Lenthang, Marlene (December 19, 2024). "Teamsters announce strike against Amazon amid holiday delivery rush". NBC News. Retrieved December 19, 2024.

- ^ Lextrait, Vincent (January 2010). "The Programming Languages Beacon, v10.0". Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ^ "All Departments". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ Rai (2021). "Amazon Tries to Crack India's Produce Market by Wooing Farmers". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on September 27, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon.com, Form 10-K, Annual Report, Filing Date Jan 30, 2013" (PDF). SEC database. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ SnapShot of amazon.com, amazonsellers.com, walmart.com Archived May 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ "Amazon launches AI assistant 'Rufus' in India". The Economic Times. August 27, 2024. ISSN 0013-0389. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ "The weird way AI assistants get their names". www.bbc.com. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Packer, George (February 17, 2014). "Cheap Words". newyorker.com. Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Amazon.com, Inc.: Shareholders Board Members Managers and Company Profile | US0231351067 | MarketScreener". www.marketscreener.com. Archived from the original on August 1, 2023. Retrieved March 6, 2024.

- ^ "Amazon.ae: Kindle Store". www.amazon.ae. Archived from the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ^ "Amazon's impact on Austria's society, sustainable development and economy". Amazon. June 18, 2021. Archived from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "About Deliveries to Denmark". Amazon.de. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "About Deliveries to Switzerland". Amazon.de. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "(Dutch) Amazon.nl officieel van start". Ecommerce News Netherlands. March 10, 2020. Archived from the original on November 29, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

(Translated) Amazon has officially launched their Dutch (Netherlands) store front Amazon.nl. Instead of only books, e-books and e-readers, the e-commerce-giant now sells numerous products.

- ^ "Amazon Prime now available to customers in Portugal". aboutamazon.eu. May 25, 2021. Archived from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "Amazon opens its first fulfilment centre in Ireland". Amazon. September 8, 2022. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "Customers in New Zealand can now shop millions of products on Amazon.com.au". Amazon.com.au. June 6, 2021. Archived from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "Amazon announces the launch of Amazon.ie in Ireland in 2025". Amazon. May 9, 2024.

- ^ "Toys R Us bankruptcy: A dot-com-era deal with Amazon marked the beginning of the end". Quartz. September 18, 2017. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ "Toys R Us wins Amazon lawsuit". BBC News. March 3, 2006. Archived from the original on January 29, 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ Metz, Rachel (June 12, 2009). "Amazon to pay Toys R Us $51M to settle suit". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 2, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ "Amazon/Borders form online partnership". CNN Money. April 11, 2001. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ "How 'Amazon factor' killed retailers like Borders, Circuit City". SFGate. July 13, 2015. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ Streitfeld, David (October 18, 2011). "Bookstores Drop Comics After Amazon Deal With DC". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Barr, Alistair (November 11, 2013). "Amazon starts Sunday delivery with US Postal Service". USA Today. Archived from the original on November 21, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ "Nike confirms 'pilot' partnership with Amazon". Engadget. June 30, 2017. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ a b Cosgrove, Elly; Thomas, Lauren (November 13, 2019). "Nike won't sell directly to Amazon anymore". CNBC. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Zimmerman, Ben. "Council Post: Why Nike Cut Ties With Amazon And What It Means For Other Retailers". Forbes.

- ^ Muldowney, Decca (August 23, 2021). "As demand for bikes surged, Amazon got in the way". The Verge. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Bhumika, Khatri (September 27, 2018). "Amazon's JV Appario Retail Clocks In $104.4 Mn For FY18". Inc42 Media. Archived from the original on October 1, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ "Booths teams up with Amazon to sell down South for the first time". Telegraph. October 11, 2017. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- ^ "Amazon strikes deal with Apple to sell new iPhones and iPads". The Verge. Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ "Apple pumps up its Amazon listings with iPhones, iPads and more". CNET. November 10, 2018. Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ "Amazon mulls new multi-billion dollar investment in Anthropic, the Information reports". Reuters. November 8, 2024.

- ^ Dulaney, Chelsey (November 30, 1999). "Amazon's Private-Label Brands Could Deliver a $1 Billion Profit Boost". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ Bensinger, Greg (May 15, 2016). "Amazon to Expand Private-Label Offerings—From Food to Diapers". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon Enters the Cloud Computing Business" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ^ "Help". Amazon. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ "Amazon.co.uk Associates: The web's most popular and successful Affiliate Program". Affiliate-program.amazon.co.uk. July 9, 2010. Archived from the original on August 26, 2008. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ "Usage of advertising networks for websites". W3Techs.com. July 22, 2014. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ "14 Easy Fundraising Ideas for Non-Profits". blisstree.com. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ "Amazon Seller Product Suggestions". Amazonservices.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ "2010 Social Shopping Study Reveals Changes in Consumers' Online Shopping Habits and Usage of Customer Reviews". the e-tailing group, PowerReviews (Press release). Business Wire. May 3, 2010. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ Spector, Robert (2002). Amazon.com. p. 132.

- ^ "BEACON SPOTLIGHT: Amazon.com rave book reviews – too good to be true?". The Cincinnati Beacon. May 25, 2010. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ a b "Amazon FAQ". Amazon. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ "Amazon.com Movers and shakers". Amazon. Archived from the original on September 7, 2011. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ "Amazon.com Author Central". Archived from the original on September 8, 2011. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ "Amazon Sales Estimator". Jungle Scout. May 15, 2017. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about Amazon.com". Amazon. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ a b Bensinger, Greg (February 2, 2016). "Amazon Plans Hundreds of Brick-and-Mortar Bookstores, Mall CEO Says". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on February 12, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Rey, Jason Del (March 8, 2017). "Amazon just confirmed its tenth bookstore, signaling this is way more than an experiment". Recode. Archived from the original on March 23, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- ^ Rosenblatt, Lauren (March 2, 2022). "Turning the page on a bookstore push launched in Seattle, Amazon ditches dozens of brick-and-mortar shops". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on March 22, 2024. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ "Amazon opening new Lehigh Valley facility, creating over 500 new jobs" Archived February 17, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, Lehigh Valley Economic Development

- ^ "Lehigh Valley's Largest Private-Sector Employers" Archived December 29, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Lehigh Valley Economic Development

- ^ Leskin, Paige. "Amazon is looking to open a brick-and-mortar liquor store in San Francisco". Business Insider. Archived from the original on August 29, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ Soper, Taylor (August 27, 2020). "Amazon opens first Fresh grocery store, debuts high-tech shopping cart in retail expansion". GeekWire. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ Molloy, David (September 28, 2021). "Amazon announces Astro the home robot". BBC News. Archived from the original on September 29, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Meyersohn, Nathaniel (January 24, 2023). "Amazon launches $5-a-month unlimited prescription plan | CNN Business". CNN. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2023.

- ^ "Amazon Jobs – Work for a Subsidiary". Archived from the original on August 1, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "Amazon Live". Amazon.com. Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- ^ "Amazon Live introduces an interactive and shoppable channel on Prime Video and Amazon Freevee". aboutamazon.com. Amazon Staff. April 16, 2024. Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- ^ Panettieri, Joe (August 3, 2020). "Cloud Market Share 2020: Amazon AWS, Microsoft Azure, Google, IBM". ChannelE2E. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Sayer, Peter (January 31, 2008). "Amazon buys Audible for US$300 million". PC World. Archived from the original on May 30, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ a b Kaufman, Leslie (March 28, 2013). "Amazon to Buy Social Site Dedicated to Sharing Books". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 29, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Montag, Ali (February 27, 2018). "Amazon buys Ring, a former 'Shark Tank' reject". CNBC. Archived from the original on February 12, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Welch, Chris (August 25, 2014). "Amazon, not Google, is buying Twitch for $970 million". The Verge. Archived from the original on July 19, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ Popper, Ben (September 30, 2013). "Field of streams: how Twitch made video games a spectator sport". The Verge. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ Needleman, Sarah E. (January 29, 2015). "Twitch's Viewers Reach 100 Million a Month". WSJ. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ "Quality Standards". Whole Foods Market. Archived from the original on December 21, 2017. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- ^ Kelleher, Kevin (August 28, 2017). "Amazon closes Whole Foods acquisition. Here's what's next". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on September 19, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Lauren (August 24, 2017). "Amazon says Whole Foods deal will close Monday, with discounts to begin then". CNBC. Archived from the original on September 13, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ McCracken, Harry (September 29, 2006). "Amazon's A9 Search as We Knew It: Dead!". PC World. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ Steele, B., Amazon is now managing its own ocean freight Archived January 29, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, engadget.com, January 27, 2017, accessed January 29, 2017

- ^ Harry Dempsey (November 17, 2020). "Amazon launches online pharmacy in challenge to traditional retailers". Financial Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ "Amazon to buy Israeli start-up Annapurna Labs". Reuters. January 22, 2015. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ^ Whitwam, Ryan (January 23, 2015). "Amazon buys secretive chip maker Annapurna Labs for $350 million". ExtremeTech. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ^ Hirschauge, Orr (January 22, 2015). "Amazon to Acquire Israeli Chip Maker Annapurna Labs". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "Is Logistics About To Get Amazon'ed?". TechCrunch. AOL. January 29, 2016. Archived from the original on June 22, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ David Z. Morris (January 14, 2016). "Amazon China Has Its Ocean Shipping License – Fortune". Fortune. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ a b "Company Overview". Brilliance Audio. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ "amazon.com Acquires Brilliance Audio". Taume News. May 27, 2007. Archived from the original on July 4, 2007. Retrieved May 28, 2007.

- ^ a b Staci D. Kramer (May 23, 2007). "Amazon Acquires Audiobook Indie Brilliance Audio". Gigaom. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c Virgil L. P. Blake (1990). "Something New Has Been Added: Aural Literacy and Libraries". Information Literacies for the Twenty-First Century. G. K. Hall & Co. pp. 203–218.

- ^ Stone, Brad (April 11, 2014). "Amazon Buys ComiXology, Takes Over Digital Leadership". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on April 11, 2014.

- ^ "Independent Publishing with CreateSpace". CreateSpace: An Amazon Company. Archived from the original on November 26, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ^ "About CreateSpace : History". CreateSpace: An Amazon Company. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ^ Novet, Jordan (February 11, 2019). "Amazon is acquiring home Wi-Fi start-up Eero". CNBC Tech. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ Kraus, Rachel (April 5, 2019). "How Amazon's $97 million Eero acquisition screwed employees and minted millionaires". Mashable. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ Whittaker, Zack (February 12, 2019). "What Amazon's purchase of Eero means for your privacy". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ Shu, Catherine (October 24, 2019). "Amazon acquires Health Navigator for Amazon Care, its pilot employee healthcare program". Tech Crunch. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ "Junglee boys strike gold on the net". Archived from the original on December 17, 2013.

- ^ "Amazon Launches Online Shopping Service In India". reuters.com. February 2, 2012. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Amazon brings the curtains down on Junglee.com, finally". vccircle.com. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (April 4, 2019). "Amazon wants to launch thousands of satellites so it can offer broadband internet from space". CNBC. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ Henry, Caleb (April 4, 2019). "Amazon planning 3,236-satellite constellation for internet connectivity". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- ^ Brodkin, Jon (July 8, 2019). "Amazon plans nationwide broadband—with both home and mobile service". ars Technica. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

Kuiper is wholly owned by Amazon, and its president is Rajeev Badyal, a former SpaceX vice president who was reportedly fired because SpaceX CEO Elon Musk was unsatisfied with his company's satellite-broadband progress.

- ^ Avalos, George (September 19, 2012). "Amazon research unit Lab 126 agrees to big lease that could bring Sunnyvale 2,600 new workers". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on December 24, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ "Amazon Kills Shelfari". The Reader's Room. January 13, 2016. Archived from the original on February 22, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Holiday, J.D. (January 13, 2016). "Shelfari Is Closing! BUT, You Can Merge Your Account with Goodreads!". The Book Marketing Network. Archived from the original on February 6, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon reaches deal to acquire Middle East e-commerce site Souq.com". CNBC. March 28, 2017. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ "Document". www.sec.gov. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ "Amazon launches new Middle East marketplace, and rebrands Souq, the company it bought for $580 million in 2017". CNBC. April 30, 2019. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ "Amazon unveils plan for a major solar power project in southern Alberta". Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions about Amazon Flex". Archived from the original on January 4, 2021. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ "Amazon Logistics / Frequently Asked Questions". Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ "Find jobs by job category". Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ "Prime Day, early holiday sales create new potential for USPS ballot delivery tie-ups". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ Annie Palmer (April 30, 2021). "Amazon is spending big to take on UPS and FedEx". Archived from the original on September 22, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ Routley, Nick (September 8, 2018). "Amazon's Massive Distribution Network in One Giant Visualization". Archived from the original on July 7, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ "9 facts about Amazon's unprecedented warehouse empire". November 21, 2017. Archived from the original on July 7, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ "Amazon announces 2 new ways it's using robots to assist employees and deliver for customers". US About Amazon. October 18, 2023. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ "Officers & Directors". Amazon. Archived from the original on March 19, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ "SWOT Analysis Amazon". Archived from the original on December 3, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ "Fortune 500 Companies 2018: Who Made the List". Fortune. Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- ^ "The Global 2000 2023". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 29, 2024. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ Streitfeld, David (January 30, 2020). "Amazon Powers Ahead With Robust Profit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ "Amazon.com, Inc. Common Stock (AMZN)". Nasdaq. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c "1997 Annual Report" (PDF). Amazon 1997 10K. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "2002 Amazon 10K" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "2007 Annual Report". Ir.aboutamazon.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019.

- ^ "2008 Annual Report". Ir.aboutamazon.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019.

- ^ "2009 Annual Report". Ir.aboutamazon.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019.

- ^ "2010 Annual Report". Ir.aboutamazon.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018.

- ^ "2011 Annual Report". Ir.aboutamazon.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018.

- ^ "2012 Annual Report". Ir.aboutamazon.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019.

- ^ "2013 Annual Report". Ir.aboutamazon.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019.

- ^ Neate, Rupert (January 29, 2015). "Amazon reports $89bn in sales last year as shares jump 11% after hours". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 16, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Roettgers, Janko (January 28, 2016). "Amazon Clocks $107 Billion In Revenue In 2015". Variety.com. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ "Amazon sales hit $136B in 2016; dollar hurts overseas business". The Seattle Times. February 2, 2017. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ "Amazon 2017 sales jump by nearly a third". BBC News. February 1, 2018. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ "2018 Annual Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ "2019 Annual Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon.com Announces Fourth Quarter Results". ir.aboutamazon.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ a b "Amazon.com, Inc. 2022 Form 10-K Annual Report". US Securities and Exchange Commission. February 3, 2022. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Gregg, Tricia; Groysberg, Boris (May 17, 2019). "Amazon's Priorities Over the Years, Based on Jeff Bezos's Letters to Shareholders". Harvard Business Review. ISSN 0017-8012. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Manjoo, Farhad (August 10, 2016). "Think Amazon's Drone Delivery Idea Is a Gimmick? Think Again". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Ritson, Mark (February 3, 2021). "Jeff Bezos's success at Amazon is down to one thing: focusing on the customer". Marketing Week. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon's Lobbying Expenditures". Opensecrets.org. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Client Profile: Amazon.com". Centre for Responsive Politics. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ Parkhurst, Emily (May 24, 2012). "Amazon shareholders met by protesters, company cuts ties with ALEC". Bizjournals.com. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Romm, Tony (August 6, 2014). "In Amazon's shopping cart: D.C. influence". Politico.com. Politico. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ Kang, Cecilia (December 27, 2015). "F.A.A. Drone Laws Start to Clash With Stricter Local Rules". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 28, 2015. Retrieved February 20, 2019.