Alcohol consumption recommendations

Recommendations for consumption of the drug alcohol (also known formally as ethanol) vary from recommendations to be alcohol-free to daily or weekly drinking "safe limits" or maximum intakes. Many governmental agencies and organizations have issued guidelines. These recommendations concerning maximum intake are distinct from any legal restrictions, for example countries with drunk driving laws or countries that have prohibited alcohol. To varying degrees, these recommendations are also distinct from the scientific evidence, such as the short-term and long-term effects of alcohol consumption.[1]

General recommendations

[edit]These guidelines apply to men and women who don't belong to populations with more specific advice.

Teetotalism advocacy by organization

[edit]

- The World Health Organization published a statement in The Lancet Public Health in April 2023 that "there is no safe amount that does not affect health"'.[2]

- The World Heart Federation (recognized by the World Health Organization as its leading NGO partner) (2022) recommends against any alcohol intake for optimal heart health.[3][4]

- The 2023 Nordic Nutrition Recommendations state "Since no safe limit for alcohol consumption can be provided, the recommendation in NNR2023 is that everyone should avoid drinking alcohol."[5]

- The American Heart Association recommends that those who do not already consume alcoholic beverages should not start doing so because of the negative long-term effects of alcohol consumption.[6][7]

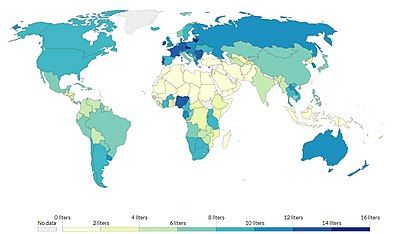

Recommended alcohol intake limitations by country

[edit]

Some governments set the same recommendation for both sexes, while others give separate limits. The guidelines give drink amounts in a variety of formats, such as standard drinks, fluid ounces, or milliliters, but have been converted to grams of ethanol for ease of comparison.

Approximately one-third of all countries advocate for complete alcohol abstinence, while all nations impose upper limits on alcohol consumption. Their daily limits range from 10-48 g per day for both men women, and weekly limits range from 27-196 g/week for men and 27-140 g/week for women. The weekly limits are lower than the daily limits, meaning intake on a particular day may be higher than one-seventh of the weekly amount, but consumption on other days of the week should be lower. The limits for women are often but not always lower than those for men.

| Country (or region) | Teetotalism recommended | Low risk | Medium to risky drinking | Heavy drinking | Details | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day | Week | Day | Week | Day | Week | Month | ||||||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |||

| Australia | 40 g | 100 g | Reference.[9][10] | |||||||||||||

| Austria | 24 g | 16 g | ||||||||||||||

| Canada | "Not drinking has benefits, such as better health, and better sleep."[11] | 27 g | The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction has a sliding scale of intakes. The scale states that at 27 g or less per week, "you are likely to avoid alcohol-related consequences for yourself or others".[11] | |||||||||||||

| Czech Republic | 24 g | 16 g | ||||||||||||||

| Denmark | 48 g | 120 g | Reference.[12] | |||||||||||||

| Finland | 168 g | 84 g | Reference.[13] | |||||||||||||

| Germany | Alcoholic beverages pose health risks and ideally should be avoided completely.[14] | The German Centre for Addiction Issues recommends everyone to reduce alcohol consumption, regardless of the amounts consumed.[14] | ||||||||||||||

| Hong Kong | 20 g | 10 g | Reference.[15] | |||||||||||||

| Iceland | 32 g | "Stop drinking before reaching five drinks on the same occasion". 1 standard drink in Iceland = 8 g ethanol. 8 g x 4 drinks = 32 g.[16] | ||||||||||||||

| Ireland | 170 g | 140 g | Reference.[17] | |||||||||||||

| Italy | 24 g | 12 g | Reference.[18] | |||||||||||||

| Japan | 40 g | 20 g | Reference.[19] | |||||||||||||

| Netherlands | Recommends an alcohol consumption level of zero grams. | 10 g | "The Health Council of the Netherlands included a guideline for alcohol consumption in the Dutch dietary guidelines 2015 (DDG-2015), which is as follows: ‘Don’t drink alcohol or no more than one glass daily’." "In the Netherlands, one regular glass of an alcoholic beverage contains approximately 10 grammes (12 millilitre) alcohol."[20] | |||||||||||||

| New Zealand | 30 g | 20 g | 150 g | 100 g | 50 g | 40 g | At least two alcohol-free days every week. 30 g for men, 20 g for women To reduce long-term health risks[21] 50 g for men, 40 g for women On any single occasion, to reduce risk of injury.[21] | |||||||||

| Norway | 20 g | 10 g | Reference.[22] | |||||||||||||

| Portugal | 37 g | 18.5 g | Reference.[23] | |||||||||||||

| Spain | 30 g | 20 g | Also suggests a maximum of no more than twice this on any one occasion.[23] | |||||||||||||

| Sweden | "Not possible to specify a limit for risk-free alcohol consumption."[24] | 48 g | 120 g | The National Board of Health and Welfare defines risky consumption as 10 (Swedish) standard drinks per week (120 g), and 4 standard drinks (48 g) or more per occasion, once per month or more often. Alcohol intervention is offered for people who exceed these recommendations.[24] | ||||||||||||

| Switzerland | 30 g | 20–24 g | Reference.[25] | |||||||||||||

| United Kingdom | "There's no completely safe level of drinking."[26] | 112 g a week, spread across 3 days or more. | Reference.[26] | |||||||||||||

| USA | "People who do not drink should not start drinking for any reason." (DGA)[27] "Adults of legal drinking age can choose not to drink." (DGA)[28] | 14-28 g (1-2 US standard drinks) (DGA)[a] | 14 g (1 US standard drink) (DGA)[a] | 0.08% BAC (NIAAA), or 70 g (SAMHSA) | 0.08% BAC (NIAAA), or 56 g (SAMHSA) | 70 grams (5 US standard drinks) or more in a single day in the past year) (CDC) | 56 grams (4 US standard drinks) or more in a single day in the past year) (CDC) | 210 g (15 US standard drinks) (NIAAA) | 112 g (8 US standard drinks) (NIAAA) | Five binge drinking sessions, each involving 70 grams (5 US standard drinks) of alcohol (SAMHSA). | Five binge drinking sessions, each involving 56 grams (4 US standard drinks) of alcohol (SAMHSA) | References: CDC.[29] NIAAA, SAMHSA.[30] 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans [a] | ||||

- Notes

- ^ a b c "The Committee recommended that adults limit alcohol intake to no more than 1 drink per day for both women and men for better health)"[31] "For those who choose to drink, intakes should be limited to 1 drink or less in a day for women and 2 drinks or less in a day for men, on days when alcohol is consumed."[28] "Alcohol has been found to increase risk for cancer, and for some types of cancer, the risk increases even at low levels of alcohol consumption (less than 1 drink in a day). Caution, therefore, is recommended."[28] "Drinking less is better for health than drinking more."[28]

By study

[edit]Emerging evidence suggests that "even drinking within the recommended limits may increase the overall risk of death from various causes, such as from several types of cancer". It is not clear that alcohol has any beneficial effects,[32] as the better health outcomes that some studies reported may be due not to alcohol consumption itself but instead be caused by "other differences in behaviors or genetics between people who drink moderately and people who don't".[33] At 20 g/day (1 large beer), the risk of developing an alcohol use disorder (AUD) is nearly 3 times higher than non-drinkers, and the risk of dying from an AUD is about 2 times higher than non-drinkers.[34] One systematic analysis found that "The level of alcohol consumption that minimised harm across health outcomes was zero (95% UI 0·0–0·8) standard drinks per week".[35] Supposing the apparent beneficial effects found in observational studies are genuine, these effects are maximized at relatively low levels of consumption, ranging from 1-18 g/day depending on age, location, and gender.[36]

Specific populations

[edit]Pregnant women

[edit]

Excessive drinking during pregnancy, especially in the first eight to twelve weeks, is associated with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders such as abnormal appearance and behavioral problems. Most guidelines state that no safe amount of alcohol consumption has been established and recommend that pregnant women abstain entirely from alcohol.[37][38] As there may be some weeks between conception and confirmation of pregnancy, most guidelines also recommend that women trying or likely to become pregnant should avoid alcohol as well.

- Australia: Total abstinence during pregnancy and if planning a pregnancy[39][40]

- Canada: "Don't drink if you are pregnant or planning to become pregnant."[41]

- France: Total abstinence[25]

- Hong Kong: "Abstinence from alcohol during pregnancy is the safest choice."[42]

- Iceland: Advise that pregnant women abstain from alcohol during pregnancy because no safe consumption level exists.[25]

- Israel: Women should avoid consuming alcohol before and during pregnancy[25][43]

- The Netherlands: Abstinence[25]

- New Zealand: "Women who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant should avoid drinking alcohol."[44]

- Norway: Abstinence[25][45]

- Sweden: Abstinence.[46]

- UK: Abstinence during pregnancy[47]

- US: Total abstinence during pregnancy and while planning to become pregnant[48]

Breastfeeding women

[edit]Moderate alcohol consumption by breastfeeding mothers can significantly affect infants. Even one or two drinks, including beer, may reduce milk intake by 20 to 23%, leading to increased agitation and poor sleep patterns. Regular heavy drinking (more than two drinks daily) can shorten breastfeeding duration and cause issues in infants, such as excessive sedation, fluid retention, and hormonal imbalances. Additionally, higher alcohol consumption may negatively impact children's academic achievement.[49]

"Alcohol passes to the baby in small amounts in breast milk. The milk will smell different to the baby and may affect their feeding, sleeping or digestion. The best advice is to avoid drinking shortly before a baby's feed."[50] "Alcohol inhibits a mother's let-down (the release of milk to the nipple). Studies have shown that babies take around 20% less milk if there's alcohol present, so they'll need to feed more often – although infants have been known to go on 'nursing strike', probably because of the altered taste of the milk."[51] "There is little research evidence available about the effect that [alcohol in breast milk] has on the baby, although practitioners report that, even at relatively low levels of drinking, it may reduce the amount of milk available and cause irritability, poor feeding and sleep disturbance in the infant. Given these concerns, a prudent approach is advised."[52]

- Australia: Total abstinence advised[39][40]

- Hong Kong: "Avoid alcohol and alcoholic drinks."[53]

- Iceland: Total abstinence advised because no safe consumption level exists.

- New Zealand: Abstinence recommended, especially in the first month of breastfeeding so that sound breastfeeding patterns can be established.[44]

- United Kingdom: Total abstinence advised by some, such as the Royal College of Midwives; others advise to limit alcohol to occasional use in small amounts not exceeding the recommended maximums for non-breastfeeding woman as this is known to cause harm, and that daily or binge drinking be avoided.[51]

Minors

[edit]Countries have different recommendations concerning the administration of alcohol to minors by adults.

- United Kingdom: Children aged under 15 should never be given alcohol, even in small quantities. Children aged 15–17 should not be given alcohol on more than one day a week – and then only under supervision from carers or parents.[54][55][56]

- Singapore: A recurring message of the Get Your Sexy Back campaign is that consuming 5 or more units of alcohol (70 g pure ethanol) at a single sitting constitutes binge drinking.[57]

Former alcoholics

[edit]- USA: According to the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, alcohol consumption is not recommended for certain individuals. Specifically, those who are in recovery from Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) or struggle to limit their alcohol intake should abstain from drinking entirely.[27]

Elderly

[edit]Caveats

[edit]Risk factors

[edit]The recommended limits for daily or weekly consumption provided in the various countries' guidelines generally apply to the average healthy adult. However, many guidelines also set out numerous conditions under which alcohol intake should be further restricted or eliminated. They may stipulate that, among other things, people with liver, kidney, or other chronic disease, cancer risk factors, smaller body size, young or advanced age, those who have experienced issues with mental health, sleep disturbances, alcohol or drug dependency or who have a close family member who has, or who are taking medication that may interact with alcohol,[58] or suffering or recovering from an illness or accident, are urged to consider, in consultation with their health professionals, a different level of alcohol use, including reduction or abstention.

Activities

[edit]Furthermore, the maximum amounts allowed do not apply to those involved with activities such as operating vehicles or machinery, risky sports or other activities, or those responsible for the safety of others.[52][59][60]

Moreover, studies suggest even moderate alcohol consumption may significantly impair – neurobiologically beneficial and -demanding – exercise (possibly including the recovery and adaptation).[61][62][63][64]

Drinking patterns

[edit]As of 2022, moderate consumption levels of alcoholic beverages are typically defined in terms of average consumption per day or week. However, drinking pattern (i.e. frequency, timing and dosage/intensity) is also significant.[33] Although countries define binge drinking in different ways, the consensus recommendation is to avoid any form of binge drinking pattern, in addition to not exceeding the daily or weekly limit.[65] Studies analyzing binge drinking have consistently found negative effects. Although there are few studies or guidelines on moderate consumption patterns,[66] the general advice is that one should spread out consumption as evenly as possible, if one is consuming a fixed amount.[26]

However, it is also easy, when drinking daily, to become habituated to alcohol's effects (consumption-induced tolerance).[67] Most people cannot accurately judge how much alcohol they are consuming,[68] particularly relative to the amounts specified in guidelines. Alcohol-free days provide a baseline and help people cut down on problematic drinking.[26] One review showed that among drinkers (not limited to moderate consumption levels), daily drinking in comparison to non-daily drinking was associated with incidence of liver cirrhosis.[69]

Alcohol promotion recommendations

[edit]Polymeal and most versions of the Mediterranean diet recommend a moderate amount of red wine, such as 150 mL (about one glass) every day, in combination with other several food items. Since about 2016, the American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association have recommended the Mediterranean diet as a healthy dietary pattern that may reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes, respectively.[70][71][72][73] The United Kingdom's National Health Service also recommends a Mediterranean diet to reduce cardiovascular disease risk.[74][75] The WHO has stated that there is currently no conclusive evidence that the potential benefits of moderate alcohol consumption for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes outweigh the increased cancer risk associated with these drinking levels for individual consumers.[76] A trial in Spain is expected to complete in 2028.[77]

Units and standard drinks

[edit]Guidelines generally give recommended amounts measured in grams (g) of pure alcohol per day or week. Some guidelines also express alcohol intake in standard drinks or units of alcohol. The size of a standard drink varies widely among the various guidelines, from 8g to 20g, as does the recommended number of standard drinks per day or week.[25][78] The standard drink size is not meant as recommendations for how much alcohol a drink should contain, but rather to give a common reference that people can use for measuring their intake, though they may or may not correspond to a typical serving size in their country.[79]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Explanatory notes

Citations

- ^ Armstrong, Elizabeth Mitchell (2017). "Making Sense of Advice About Drinking During Pregnancy: Does Evidence Even Matter?". The Journal of Perinatal Education. 26 (2): 65–69. doi:10.1891/1058-1243.26.2.65. PMC 6353268. PMID 30723369.

- ^ "No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ Arora, Monika; ElSayed, Ahmed; Beger, Birgit; Naidoo, Pamela; Shilton, Trevor; Jain, Neha; Armstrong-Walenczak, Kelcey; Mwangi, Jeremiah; Wang, Yunshu; Eiselé, Jean-Luc; Pinto, Fausto J.; Champagne, Beatriz M. (22 July 2022). "The Impact of Alcohol Consumption on Cardiovascular Health: Myths and Measures". Global Heart. 17 (1): 45. doi:10.5334/gh.1132. ISSN 2211-8179. PMC 9306675. PMID 36051324.

- ^ Salamon, Maureen (1 May 2022). "Want a healthier heart? Seriously consider skipping the drinks". Harvard Health. Archived from the original on 31 May 2024. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ "Less meat, more plant-based: Here are the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023". www.norden.org. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ Mechanick, Jeffrey I.; Kushner, Robert F. (21 April 2016). Lifestyle Medicine: A Manual for Clinical Practice. Springer Science. p. 153. ISBN 978-3-319-24687-1.

However, even light alcohol use (≤1 drink daily) increases the risk of developing cancer, and heavier use (≥2-4 drinks daily) significantly increases morbidity and mortality. Given these and other risks, the American Heart Association cautions that, if they do not already drink alcohol, people should not start drinking for the purported cardiovascular benefits of alcohol.

- ^ Deedwania, Prakash (12 January 2015). "Alcohol and Heart Health". American Heart Association (AHA). Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ "Alcohol consumption per person". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ "Managing your alcohol intake". 21 February 2024. Archived from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol". Nhmrc.gov.au. 2020. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Canada's Guidance on Alcohol and Health". ccsa.ca. Archived from the original on 11 September 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ "Anbefalinger om alkohol". Sundhedsstyrelsen (in Danish). Archived from the original on 22 March 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ "Alkoholin riskirajat". Alko (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Empfehlungen zum Umgang mit Alkohol" (PDF). Deutsche Hauptstelle für Suchtfragen (in German). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ Department of Health Action Plan to Reduce Alcohol-related Harm in Hong Kong Archived 24 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine September 2011

- ^ "Recommendations from the Directorate of Health". Ísland.is. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ "Health chiefs cut limits on safe drinking". Alcohol Action Ireland. 26 June 2012. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ a b Alcol, zero o il meno possibile Archived 16 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine January 2022

- ^ "Japan draws up guidelines on alcohol consumption". The Japan Times. 19 February 2024. Archived from the original on 24 March 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ https://www.healthcouncil.nl/binaries/healthcouncil/documenten/advisory-reports/2023/02/07/dutch-dietary-guidelines-for-people-with-atherosclerotic-cardiovascular-disease/I-Background-doc-Alcohol_DDG-for-people-with-ASCVD+mz.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand (ALAC) What's in a Standard Drink Archived 23 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Anbefaling angående inntak av alkohol ved forebygging av hjerte- og karsykdom". Helsedirektoratet (in Norwegian). 5 March 2018. Archived from the original on 22 March 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ a b Drinking and You Drinking guidelines — units of alcohol Archived 8 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Till hälso- och sjukvården: Nya gränser för riskbruk av alkohol". Socialstyrelsen (in Swedish). 15 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Drinking Guidelines: General Population". IARD.org. International Alliance for Responsible Drinking. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Drink less - Better Health". nhs.uk. 6 July 2021. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ a b "What Are the U.S. Guidelines for Drinking? - Rethinking Drinking | NIAAA". rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov.

- ^ a b c d https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans-2020-2025.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "NHIS - Adult Alcohol Use - Glossary". www.cdc.gov. 10 May 2019.

- ^ "Drinking Levels and Patterns Defined | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)". www.niaaa.nih.gov.

- ^ Snetselaar, LG; de Jesus, JM; DeSilva, DM; Stoody, EE (November 2021). "Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025: Understanding the Scientific Process, Guidelines, and Key Recommendations". Nutrition today. 56 (6): 287–295. doi:10.1097/NT.0000000000000512. PMC 8713704. PMID 34987271.

- ^ Tsai, MK; Gao, W; Wen, CP (3 July 2023). "The relationship between alcohol consumption and health: J-shaped or less is more?". BMC Medicine. 21 (1): 228. doi:10.1186/s12916-023-02911-w. PMC 10318728. PMID 37400823.

- ^ a b "Facts about moderate drinking | CDC". CDC. 19 April 2022. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Carr, Tessa; Kilian, Carolin; Llamosas-Falcón, Laura; Zhu, Yachen; Lasserre, Aurélie M.; Puka, Klajdi; Probst, Charlotte (2024). "The risk relationships between alcohol consumption, alcohol use disorder and alcohol use disorder mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Addiction. 119 (7): 1174–1187. doi:10.1111/add.16456. ISSN 0965-2140. PMC 11156554. PMID 38450868.

- ^ Griswold, Max G.; Fullman, Nancy; Hawley, Caitlin; et al. (22 September 2018). "Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016". The Lancet. 392 (10152): 1015–1035. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 6148333. PMID 30146330.

- ^ GBD 2020 Alcohol Collaboration (July 2022). "Population-level risks of alcohol consumption by amount, geography, age, sex, and year: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2020". The Lancet. 400 (10347): 185–235. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00847-9. PMC 9289789. PMID 35843246.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ NICE, Routine antenatal care for healthy pregnant women Archived 11 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine March 2007

- ^ BBC 'No alcohol in pregnancy' advised Archived 30 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine 25 May 2007

- ^ a b National Health and Medical Research Council 2020 Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol Archived 13 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b National Health and Medical Research Council 2009 Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol: Frequently Asked Questions Archived 13 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Canadian Center on Substance Abuse Canada's Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines Archived 20 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Department of Health". Archived from the original on 17 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Proper Nutrition during Pregnancy". Ministry of Health. State of Israel. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ a b New Zealand Ministry of Health Manatū Hauora Food and Nutrition Guidelines for Healthy Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women Archived 26 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Alkovett for den lille" (PDF). avogtil.no/. AV OG TIL. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "Ej längre bruk av alkohol vid graviditet". roi.socialstyrelsen.se (in Swedish). February 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ^ "New recommended drinking guidelines welcomed by NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 8 January 2016. Archived from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ 'USDA, Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005, Chapter 9: Alcoholic Beverages Archived 1 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Alcohol". 2006. PMID 30000529.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Alcohol and pregnancy". Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ^ a b "Alcohol and breastfeeding (2009) - Retrieved 23 May 2014". Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ a b Australian Guidelines 2009

- ^ "Family Health Service, Department of Health" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Consultation on children, young people and alcohol". Dcsf.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ Parents back alcohol free childhood 17 December 2009

- ^ BBC 'No alcohol' urged for under-15s Archived 10 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine 29 January 2009

- ^ "Young and Smashed". SoShiok.com. 4 June 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Weathermon R, Crabb DW (1999). "Alcohol and medication interactions" (PDF). Alcohol Res Health. 23 (1): 40–54. PMC 6761694. PMID 10890797. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- ^ Centre for Addiction and Mental Health / Centre de toxicomanie et de santé mentale Low-Risk Drinking Guidelines Archived 2 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand (ALAC) Low Risk Drinking Archived 9 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ El-Sayed, Mahmoud S.; Ali, Nagia; Ali, Zeinab El-Sayed (1 March 2005). "Interaction Between Alcohol and Exercise". Sports Medicine. 35 (3): 257–269. doi:10.2165/00007256-200535030-00005. ISSN 1179-2035. PMID 15730339. S2CID 33487248.

- ^ Barnes, Matthew. J.; Mündel, Toby; Stannard, Stephen. R. (1 January 2010). "Acute alcohol consumption aggravates the decline in muscle performance following strenuous eccentric exercise". Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 13 (1): 189–193. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2008.12.627. ISSN 1440-2440. PMID 19230764.

- ^ Lakićević, Nemanja (September 2019). "The Effects of Alcohol Consumption on Recovery Following Resistance Exercise: A Systematic Review". Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 4 (3): 41. doi:10.3390/jfmk4030041. ISSN 2411-5142. PMC 7739274. PMID 33467356.

- ^ Vella, Luke D.; Cameron-Smith, David (August 2010). "Alcohol, Athletic Performance and Recovery". Nutrients. 2 (8): 781–789. doi:10.3390/nu2080781. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 3257708. PMID 22254055.

- ^ "Binge drinking". British Medical Association. March 2005. Archived from the original on 3 April 2005. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ Heckley, Gawain; Jarl, Johan; Gerdtham, Ulf-G (2017). "Frequency and intensity of alcohol consumption: new evidence from Sweden". The European Journal of Health Economics. 18 (4): 495–517. doi:10.1007/s10198-016-0805-2. ISSN 1618-7598. PMC 5387029. PMID 27282872.

- ^ "Mayo Clinic Q and A: Is daily drinking problem drinking?". Mayo Clinic News Network (in Spanish). 16 February 2018. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Monk, Rebecca Louise; Heim, Derek; Qureshi, Adam; Price, Alan (19 May 2015). ""I Have No Clue What I Drunk Last Night" Using Smartphone Technology to Compare In-Vivo and Retrospective Self-Reports of Alcohol Consumption". PLOS ONE. 10 (5): e0126209. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1026209M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0126209. PMC 4437777. PMID 25992573.

- ^ Roerecke, Michael; Vafaei, Afshin; Hasan, Omer SM; Chrystoja, Bethany R; Cruz, Marcus; Lee, Roy; Neuman, Manuela G; Rehm, Jürgen (October 2019). "Alcohol consumption and risk of liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 114 (10): 1574–1586. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000340. ISSN 0002-9270. PMC 6776700. PMID 31464740.

- ^ Van Horn L, Carson JA, Appel LJ, et al. (29 November 2016). "Recommended Dietary Pattern to Achieve Adherence to the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) Guidelines: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 134 (22): e505–e529. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000462. PMID 27789558. S2CID 37889352.

- ^ Evert, Alison B.; Dennison, Michelle; Gardner, Christopher D.; et al. (May 2019). "Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report". Diabetes Care (Professional society guidelines). 42 (5): 731–754. doi:10.2337/dci19-0014. PMC 7011201. PMID 31000505.

- ^ American Diabetes Association (January 2019). "5. Lifestyle Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019". Diabetes Care. 42 (Suppl 1): S46–S60. doi:10.2337/dc19-S005. PMID 30559231.

- ^ "8 eating plans for patients with prediabetes". American Medical Association. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Prevention". nhs.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Mediterranean diet". uhcw.nhs.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health". World Health Organization. 4 January 2023. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ Martínez-González, Miguel A. "UNATI - A non-inferiority randomized trial testing an advice of moderate drinking pattern versus advice on abstention on major disease and mortality" (PDF). CORDIS | European Commission. doi:10.3030/101097681.

- ^ Kalinowski, Agnieszka; Humphreys, Keith (1 July 2016). "Governmental standard drink definitions and low-risk alcohol consumption guidelines in 37 countries". Addiction. 111 (7): 1293–1298. doi:10.1111/add.13341. ISSN 1360-0443. PMID 27073140.

- ^ Mongan, Deirdre; Long, Jean (22 May 2015). "Standard drink measures throughout Europe; peoples' understanding of standard drinks and their use in drinking guidelines, alcohol surveys and labelling" (PDF). Reducing Alcohol Related Harm. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

External links

[edit]- National Health and Medical Research Council (2020). Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol. Commonwealth of Australia. ISBN 978-1-86496-071-6.

- The Brilliant Breastfeeding Alcohol and Breastfeeding Archived 17 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine page describes pros and cons of drinking alcohol while breastfeeding.

- Drinking Guidelines: General Population by Country IARD.org

- Drinking Guidelines: Pregnancy and Breastfeeding by Country IARD.org