White-cheeked barbet

| White-cheeked barbet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Piciformes |

| Family: | Megalaimidae |

| Genus: | Psilopogon |

| Species: | P. viridis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Psilopogon viridis | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Bucco viridis, Thereiceryx viridis, Megalaima viridis | |

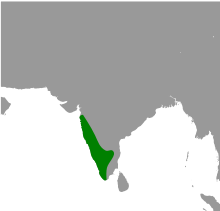

The white-cheeked barbet or small green barbet (Psilopogon viridis) is a species of Asian barbet found in southern India. It is very similar to the more widespread brown-headed barbet (or large green barbet, Psilopogon zeylanicus), but this species has a distinctive supercilium and a broad white cheek stripe below the eye and is found in the forest areas of the Western Ghats, parts of the Eastern Ghats and adjoining hills. The brown-headed barbet has an orange eye-ring but the calls are very similar and the two species occur together in some of the drier forests to the east of the Western Ghats. Like all other Asian barbets, they are mainly frugivorous (although they may sometimes eat insects), and use their bills to excavate nest cavities in trees.

Taxonomy

[edit]Bucco viridis was the scientific name proposed by Pieter Boddaert in 1783 for a green barbet that had been described by Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon in 1780 based on a specimen collected in India.[2][3] It was illustrated by François-Nicolas Martinet in a hand-coloured plate.[4] It was placed in the genus Megalaima proposed by George Robert Gray in 1842 who suggested to use this name instead of Bucco.[5] Its type locality is Mahé, Puducherry in southwestern India. It is a monotypic species.[6]

In 2004, molecular phylogenetic research of barbets revealed that the Megalaima species form a clade, which also includes the fire-tufted barbet, the only species placed in the genus Psilopogon at the time. Asian barbets were therefore reclassified under the genus Psilopogon.[7]

Results of a phylogenetic study of Asian barbets published in 2013 indicate that the white-cheeked barbet is most closely related to the yellow-fronted barbet (P. flavifrons), which is endemic to Sri Lanka.[8]

The relationship of the white-cheeked barbet with some close relatives in its taxon is illustrated below.[8]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

[edit]The white-cheeked barbet is 16.5–18.5 cm (6.5–7.3 in) in length. It has a brownish head streaked with white, sometimes giving it a capped appearance. The bill is pale pink.[9] Size varies from the larger northern birds to the southern ones.[10]

Like many other Asian barbets, white-cheeked barbets are green, sit still, and perch upright, making them difficult to spot. During the breeding season which begins at the start of summer their calls become loud and constant especially in the mornings. The call, a monotonous Kot-roo...Kotroo... starting with an explosive trrr is not easily differentiated from that of the brown-headed barbet. During hot afternoons, they may also utter a single note wut not unlike the call of collared scops owl or coppersmith barbet. Other harsh calls are produced during aggressive encounters.[11]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The main range is along the Western Ghats south from the Surat Dangs and along the associated hills of southern India into parts of the southern Eastern Ghats mainly in the Shevaroy and Chitteri Hills.[11][9] In some areas, it has been suggested that this species may have displaced the brown-headed barbet which was formerly the dominant barbet species.[12]

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]

The Indian ornithologist Salim Ali noted that some individuals call in the night during the breeding season, but this has been questioned by other observers who noted that they appear to be strictly diurnal.[13]

Food and feeding

[edit]These barbets are arboreal and will rarely visit the ground. They obtain most of the water they need from their fruit diet. When water is available in a tree hole, they will sometimes drink and bathe.[14]

These birds are mostly frugivorous, but will take winged termites and other insects opportunistically. They feed on the fruits of various Ficus species including Ficus benjamina and Ficus mysorensis,[15] and introduced fruit trees such as Muntingia calabura. When foraging they are quite aggressive and will attempt to chase other barbets, koels and other frugivores.[9][16]

These barbets play an important role in forests as seed dispersal agents.[17][18][19] They also visit the flowers of Bombax for nectar and may be involved in pollination.[11]

Their fruit eating makes them a minor nuisance in fruit orchards although they are noted as having a beneficial effect in coffee plantations.[20][21]

A species of tick in the genus Haemaphysalis is known to be specific in its parasitic association with this species[22] and some species of Leucocytozoon are known to be blood parasites.[23] Some species of Haemaphysalis are known to carry the virus responsible for the Kyasanur forest disease.[24] Shikras have been recorded preying on adults.[25]

Breeding

[edit]

In Periyar Tiger Reserve, white-cheeked barbets begin breeding in December and continue to nest until May. They are believed to form a pair bond that lasts for longer than a single breeding season. Calling is intense during the courtship period. Courtship feeding of the female by the male is usual prior to copulation. Calling intensity drops after the hatching of the eggs.[25] The nest hole is usually made in dead branches. These barbets are aggressive towards smaller hole-nesters such as the Malabar barbet, sometimes destroying their nests by pecking at the entrance. Both sexes excavate the nest and it can take about 20 days to complete the nest. Eggs are laid about 3–5 days after nest excavation. About 3 eggs are laid. The incubation period is 14 to 15 days. During the day both sexes incubate, but at night, only the female sits on the eggs. The pair will defend their nests from palm squirrels which sometimes prey on the eggs. Chicks are fed an insect rich diet. The young leave the nest after 36 to 38 days.[25]

These birds are primary cavity nesters, chiseling out the trunk or a vertical branch of tree with a round entry hole. They breed from December to July, sometimes raising two broods.[9] Favoured nest trees in urban areas include gulmohur (Delonix regia) and African tulip (Spathodea campanulata). These nest holes may also be used as roosts.[26] They may reuse the same nest tree each year but often excavate a new entrance hole.[27][28]

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Psilopogon viridis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22681603A92913200. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22681603A92913200.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Boddaert, P. (1783). "870. Barbu verd". Table des Planches enluminées d'Histoire Naturelle de M. D'Aubenton : avec les denominations de M.M. de Buffon, Brisson, Edwards, Linnaeus et Latham, precedé d'une notice des principaux ouvrages zoologiques enluminés (in French). Utrecht. p. 53.

- ^ Buffon, G.-L. L. (1780). "Le barbu vert". Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux (in French). Vol. 13. Paris: L'Imprimerie Royale. p. 161.

- ^ Buffon, G.-L. L.; Martinet, F.-N.; Daubenton, E.-L.; Daubenton, L.-J.-M. (1765–1783). "Barbu de Mahé". Planches Enluminées D'Histoire Naturelle. Vol. 9. Paris: L'Imprimerie Royale. p. Plate 870.

- ^ Gray, G. R. (1842). "Appendix to a List of the Genera of Birds". A List of the Genera of Birds (Second ed.). London: R. and J. E. Taylor. p. 12.

- ^ Peters, J. L., ed. (1948). "Genus Megalaima G. R. Gray". Check-list of Birds of the World. Vol. 6. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 31–40.

- ^ Moyle, R. G. (2004). "Phylogenetics of barbets (Aves: Piciformes) based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequence data". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 30 (1): 187–200. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00179-9. PMID 15022769.

- ^ a b Den Tex, R.-J.; Leonard, J. A. (2013). "A molecular phylogeny of Asian barbets: Speciation and extinction in the tropics". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 68 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2013.03.004. PMID 23511217.

- ^ a b c d Rasmussen, P.C. & Anderton, J.C. (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions. p. 277.

- ^ Blanford, W. T. (1895). "Thereiceryx viridis. The Small Green Barbet". The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Vol. 3, Birds (First ed.). London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b c Ali, S. & Ripley, S.D. (1983). Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan. Vol. 4 (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 155–156. ISBN 0-19-562063-1.

- ^ George, J., ed. (1994). Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Bangalore. Bangalore: Birdwatchers' Field Club of Bangalore.

- ^ Neelakantan, K.K. (1964). "The Green Barbet Megalaima viridis". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 4 (4): 6–7.

- ^ Yahya, H.S.A. (1991). "Drinking and bathing behaviour of the Large Green Megalaima zeylanica (Gmelin) and the Small Green M. viridis (Boddaert) Barbets". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 88 (3): 454–455.

- ^ Shanahan, M.; Samson S.; Compton, S.G. & Corlett, R. (2001). "Fig-eating by vertebrate frugivores: a global review" (PDF). Biological Reviews. 76 (4): 529–572. doi:10.1017/S1464793101005760. PMID 11762492. S2CID 27827864.

- ^ Kumar, T.N.V. & Zacharias, V.J. (1993). "Time budgets in fruit-eating Koel Eudynamys scolopacea and Barbet Megalaima viridis". In Verghese, A.; Sridhar, S. & Chakravarthy, A.K. (eds.). Bird Conservation: Strategies for the Nineties and Beyond. Bangalore: Ornithological Society of India. pp. 161–163.

- ^ Ganesh, T. & Davidar, P. (2001). "Dispersal modes of tree species in the wet forests of southern Western Ghats" (PDF). Current Science. 80 (3): 394–399. JSTOR 24105700.

- ^ Ganesh T. & Davidar, P. (1999). "Fruit biomass and relative abundance of frugivores in a rain forest of southern Western Ghats, India". Journal of Tropical Ecology. 15 (4): 399–413. doi:10.1017/S0266467499000917. S2CID 84587797.

- ^ Ganesh T.; Davidar, P. (1997). "Flowering phenology and flower predation of Cullenia exarillata (Bombacaceae) by arboreal vertebrates in Western Ghats, India". Journal of Tropical Ecology. 13 (3): 459–468. doi:10.1017/S0266467400010622. S2CID 83574443.

- ^ Yahya, H.S.A. (1983). "Observations on the feeding behaviour of barbet (Megalaima sp.) in coffee estates of South India". Journal of Coffee Research. 12 (3): 72–76.

- ^ Chakravarthy A.K. (2004). "Role of vertebrates in inflicting diseases in fruit orchards and their management in fruit and vegetable diseases". In Mukerji, K.G. (ed.). Fruit and Vegetable Diseases. Vol. 1. pp. 95–142. doi:10.1007/0-306-48575-3_4.

- ^ Rajagopalan P.K. (1963). "Haemaphysalis megalaimae sp. n., a new tick from the small green barbet (Megalaima viridis) in India". Journal of Parasitology. 49 (2): 340–345. doi:10.2307/3276011. JSTOR 3276011.

- ^ Jones, Hugh I.; Sehgal, R.N.M.; Smith, T.B. (2005). "Leucocytozoon (Apicomplexa: Leucocytozoidae) from West African birds, with descriptions of two species" (PDF). Journal of Parasitology. 91 (2): 397–401. doi:10.1645/GE-3409. PMID 15986615. S2CID 7661872.

- ^ Boshell M., Jorge (1969). "Kyasanur Forest Disease: ecologic considerations". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 18 (1): 67–80. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1969.18.67. PMID 5812658.

- ^ a b c Yahya, H.S.A. (1988). "Breeding biology of Barbets, Megalaima spp. (Capitonidae: Piciformes) at Periyar Tiger Reserve, Kerala". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 85 (3): 493–511.

- ^ Neelakantan, K.K. (1964). "The roosting habits of the barbet". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 4 (3): 1–2.

- ^ Baker, ECS (1927). The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Birds. Volume (4. Second ed.). Taylor and Francis, London. p. 114.

- ^ Neelakantan, K.K. (1964). "More about the Green Barbet Megalaima viridis". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 4 (9): 5–7.

Further reading

[edit]- Sridhar Hari, Sankar K (2008). "Effects of habitat degradation on mixed-species bird flocks in Indian rain forests". Journal of Tropical Ecology. 24 (2): 135–147. doi:10.1017/S0266467408004823. S2CID 86835417.