Vera Danchakoff

Vera Mikhaĭlovna Danchakoff[note 1] (née Grigorevskaya, March 21, 1879 – September 22, 1950) was an anatomist, cell biologist and embryologist from the Russian Empire. In 1908 she was the first woman in the Russian Empire to be appointed as a professor and she became a pioneer in stem cell research. She emigrated to the United States in 1915 where she was a leading exponent of the idea that all types of blood cell develop from a single type of cell. She has sometimes been called "the mother of stem cells". She later returned to Europe to continue with her research.

Early life

[edit]

Danchakoff was born in St Petersburg where her parents wanted her to study music or drawing. Determined otherwise, she left home to take a degree in natural sciences before moving to Lausanne University for a medical degree, producing her thesis in 1906.[1][2][3] Returning to Russia she took a Russian medical degree at Kharkov University and then became the first woman to be awarded a doctorate in medical sciences at the St Petersburg Academy of Medicine – Russia's first medical college for women.[3]

She married and her daughter, Vera Evgenevna, who was born in 1902 in Zurich, went on to study at Columbia University and to marry Mikhail Lavrentyev, the mathematician.[4][5][6][7] In 1915 Danchakoff emigrated to the United States where she was politically active, writing as the New York correspondent of the Moscow newspaper Utro Rossi (Russian Morning) and by helping the American Relief Administration with publicising the difficulties of Soviet scientists in working in Russia during the Great War, the Bolshevik Revolution and afterwards.[1] During the Russian famine of 1921–22 Danchakoff appealed for food parcels to be sent to Russia by publicizing the correspondence she had been receiving from scientific colleagues in Russia. Although internationally eminent, they had been denounced as "parasites and idlers" and were dying of starvation.[8]

At the time there was a strong Russian émigré community in New York and, with her husband, Danchakoff hosted lavish gatherings of friends. She was a talented pianist and she took part in the musical evenings of Juan and Olga Codina, who were professional singers. She used to look after their daughter Lina when her parents were away on their extended tours – Lina later was to marry Serge Prokofiev.[1]

Scientific career

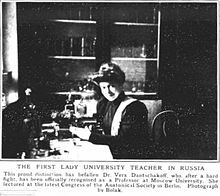

[edit]In 1908 Danchakoff became an assistant professor in histology and embryology at Moscow University – the first woman to become a professor in Russia.[7][9] In 1915 she emigrated to the United States where she first worked at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York City. Then at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, led by Thomas Hunt Morgan, she was "instructor in anatomy" at a time when women were first being allowed admittance as students.[1][10] In a 1916 lecture she said

"... the erythrocytes, the small lymphocytes, the different leucocytes, the wandering cells of the connective tissue, the mast cells, and the plasma cells - all these cells are different cell units, morphologically as well as physiologically but in the early embryonic stages they all had a common mother cell, and this mother cell is preserved in the adult organism and becomes the source of differentiation and regeneration and most probably also the source of pathological proliferation."

— Vera Danchakoff, Danchakoff, Vera (1916). "Origin of blood cells. Development of the haematopoitic organs and regeneration of the blood cells from the standpoint of the monophyletic school". Anatomical Record. 10 (5): 397–414. doi:10.1002/ar.1090100506. S2CID 85116407.[11]

In his 2001 keynote address to the Acute Leukemia Forum Marshall Lichtman described her presentation as an "extraordinary lecture" and considered that "The rest of the century has been spent filling in the details of [her] experimental insights!".[12] It has been claimed that a paper of Danchakoff's is the first publication to use the term "stem cell", for example "These stem cells develop on the one hand into the small lymphocytes, and on the other hand into granulocytoblasts, and further into granulocytes".[13] It has now been confirmed that hematopoietic stem cells give rise to all other blood cells.[14]

For these reasons Danchakoff has sometimes been called the "mother of stem cells".[7][15] However, in terms of the actual terminology, in 1909 Alexander A. Maximow wrote in German of "Stammzelle" for the same concept in his paper "The lymphocyte as a stem cell, common to different blood elements in embryonic development and during the post-fetal life of mammals" (English translation[16]).[17]

In 1916 Danchakoff and James Bumgardner Murphy independently reported on a surprising discovery concerning the chick embryo – one that turned out to be of great importance. When the embryo was injected with adult lymphocytes the spleen greatly enlarged. With other types of cell this did not occur. Murphy's and Danchakoff's explanations for the effect were wrong but much later these observations led to an understanding of lymphocyte migration and graft-versus-host disease.[15]

By 1919 Danchakoff was a full professor of anatomy in Columbia's College of Physicians and Surgeons.[3] In 1934 she left Columbia and until 1937 worked in the Department of Histology and Embryology at the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences.[19] In 1938 she conducted important experiments which involved exposing female guinea pig foetuses to testosterone. She showed for the first time that this can give rise to an increase of masculine sexual behavior in adulthood.[20][21]

Danchakoff published many books as well as scientific papers, possibly her last publications being Le sexe; rôle de l'hérédité et des hormones dans sa réalisation in 1949 and Effects of cancer provoking chemical substances on gravid guinea pigs and their fruits in 1950.[22][23][24]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Morrison, Simon (2013). The love and wars of Lina Prokofiev : the story of Lina and Serge Prokofiev. London: Harvill Secker. pp. 21–23, 39, 296. ISBN 9781846557316.

- ^ K voprosu o neĭrofibrilli︠a︡rnom apparati︠e︡ nervnykh kli︠e︡tok i ego izmi︠e︡nenīi︠a︡kh pri bi︠e︡shenstvi︠e︡ : ėksperimentalʹnoe izsli︠e︡dovanīe : dissertat︠s︡īi︠a︡ na stepenʹ doktora medit︠s︡iny. WorldCat. OCLC 614270909.

- ^ a b c Wisehart, M.K. (9 November 1919). "Woman Doctor Blazes New Trail to Immunity From Disease". New York Herald. p. 81 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Lavrentiev, Michael A." youwikifr.top. Retrieved 14 August 2016.[permanent dead link] quoting an article in Vedomosti, 14 April 1995

- ^ "Век Лаврентьева (2000) - З.М.Ибрагимова. Низкий поклон, Вера Евгеньевна ..." www.prometeus.nsc.ru. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ Tatarchenko, Ksenia (November 2013). A house with the window to the west: the akademgorodok computer center (1958-1993) (PDF). Princeton University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2014.

- ^ a b c Чёрная, Ю. "ЛАВРЕНТЬЕВ И ГЕНЕТИКА". Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Eminent Scientists Starving in Russia". New York Times. Newspapers.com. 23 April 1922. p. 34.

- ^ "The First University Lady Teacher in Russia". The Graphic. 20 June 1908. p. 28.

- ^ "News". British Medical Journal: 390. 1916.

- ^ Quoted in Lichtman, M.A. (October 2001). "The stem cell in the pathogenesis and treatment of myelogenous leukemia: a perspective". Leukemia. 15 (10): 1489–1494. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2402247. PMID 11587204.

- ^ Lichtman, M.A. (October 2001). "The stem cell in the pathogenesis and treatment of myelogenous leukemia: a perspective". Leukemia. 15 (10): 1489–1494. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2402247. PMID 11587204.

- ^ Qureshi, Nasib; Caplan, Arnold I; Babiss, Lee E. (2 December 2015). Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine: Science, Regulation and Business Strategies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 582. ISBN 978-1-119-97139-9. referring to Danchakoff, Vera (July 1916). "The differentiation of cells as a criterion for cell identification, considered in relation to the small cortical cells of the thymus". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 24 (1): 87–105. doi:10.1084/jem.24.1.87. PMC 2125411. PMID 19868031.

The proliferation of the young stem cells and their simultaneous differentiation in various directions, according to environmental conditions, lead to considerable diversity between cells, coexisting in time and place; and the various stages of different cells may sometimes manifest merely slight and doubtful peculiarities in their structure.

- ^ Zhao, Robert Chunhua (14 September 2015). "Chapter 5". Stem Cells: Basics and Clinical Translation. Springer. p. 111. ISBN 978-94-017-7273-0.

- ^ a b Hamilton, David (2012). A History of Organ Transplantation: Ancient Legends to Modern Practice. University of Pittsburgh. pp. 112–113, 452. ISBN 978-0-8229-7784-1.

- ^ Koltzenburg, Claudia; et al. (2009). "The lymphocyte as a stem cell, common to different blood elements in embryonic development and during the post-fetal life of mammals". Cellular Therapy and Transplantation. 1 (3). Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ Maximow, A. (1909). "Der Lymphozyt als gemeinsame Stammzelle der verschiedenen Blutelemente in der embryonalen Entwicklung und im postfetalen Leben der Säugetiere". Folia Haematologica. 8: 125–134. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ Harvey M. Good (2006). The Medicaments of Cellular Therapy. Trafford Publishing. pp. 82–. ISBN 978-1-4120-7200-7.

- ^ "Department of Histology and Embryology". Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017.

- ^ Swaab, D.F.; Hofman, M.A. (1984). "Sexual Differentiation of the Human Brain, a Historical Perspectivees". In De Fries, G.J.; et al. (eds.). Sex Differences in the Brain the Relation Between Structure and Function. Burlington: Elsevier. p. 362. ISBN 978-0-08-086186-9.

- ^ Jordan-Young, Rebecca M. (7 January 2011). Brain Storm. Harvard University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-674-05879-8.

- ^ "Results for 'au:vera danchakoff' [WorldCat.org]". www.worldcat.org.

"Results for 'au:dantchakoff' [WorldCat.org]". www.worldcat.org. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

"Results for 'au:dantschakoff' [WorldCat.org]". www.worldcat.org. - ^ Dantchakoff, Vera (1 January 1949). Le sexe: rôle de l'hérédité et des hormones dans sa réalisation (in French). Presses universitaires de France. OCLC 369813747.

- ^ Danchakoff, Vera (July 1950). "Effects of cancer provoking chemical substances on gravid guinea pigs and their fruits". Acta––Unio Internationalis Contra Cancrum. 7 (1): 87–90. PMID 14789590.

- Embryologists from the Russian Empire

- Women anatomists

- 20th-century anatomists

- Anatomists from the Russian Empire

- 1879 births

- 1950 deaths

- Scientists from Saint Petersburg

- Academic staff of Moscow State University

- Columbia University faculty

- Rockefeller University faculty

- Stem cell researchers

- Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States

- Women scientists from the Russian Empire