User talk:Wikirictor/articlebase

German Antarctic Expedition (1938–1939)

[edit]

The German Antarctic Expedition 1938/39, led by German Navy captain Alfred Ritscher (1879–1963), was the third official Antarctic expedition of the German Reich, by order of the "Commissioner for the Four-Year Plan" Hermann Göring. Councilor of state Helmuth Wohlthat was mandated with planning and preparation. The expedition's main objective was of economic nature, in particular the establishement of a whaling station and the acquisition of fishing grounds for a German whaling fleet in order to reduce the Reich's dependence on the import of industrial oils, fats and dietary fats. Preparations took place under strict secrecy as the enterprise was also tasked to make a feasibility assessment for a future occupation of Antarctic territory in the region between 20 ° West and 20 ° East.[1][2]

Preparations

[edit]In July 1938, Captain Alfred Ritscher received a mandate to launch preparations for an Antarctic expedition and within a few months he managed to bring about logistics, equippment and organizational measures for a topographical and marine survey expedition. Whale oil was then the most important raw material for the production of margarine and soap in Germany and the country was the second largest purchaser of Norwegian whale oil, importing some 200,000 metric tonnes annually. Dependence on imports and the forthcoming war was considered to put too much strain on Germany's foreign currency reserves. Supported by whaler Otto Kraul marine explorations were to be undertaken in order to set up a base for a whaling fleet and aireal photo surveys were to be carried out to map territory.

With only six months available for preparatory work, Ritscher had to rely on the antiquated MS Schwabenland ship and aircraft of Deutsche Lufthansa's Atlantic Service, with which a scientific program along the coast was to be carried out and retrieve biologic, meteorologic, oceanographic and geomagnetic studies. Aireal surveys of the unknown hinterland were to be taken with two Dornier Do J II seaplanes, named Boreas and Passat, that had to be launched via a steam catapult on the MS Schwabenland expedition ship. After urgent repairs on the ship and the two seaplanes, the 33 expedition members plus a crew of 24 on the Schwabenland left Hamburg on December 17, 1938.[3]

Expedition

[edit]

The Expedition reached the Princess Martha Coast on January 19, 1939 and was active along the Queen Maud Land coast from 19 January to 15 February 1939. In seven survey flights between January 20 and February 5, 1939, an area of approx. 350,000 km² was photogrammetrically mapped. Completely unknown ice-free mountain ranges, several small ice-free lakes were discovered in the hinterland. The ice-free Schirmacher Oasis, which now hosts the Maitri and Novolazarevskaya research stations, was spotted from the air by Richard Schirmacher (who named it after himself). At the turning points of the flight polygons, 1.2 m (3.9 ft) long aluminum arrows, with 30 cm (12 in) steel cones and three upper stabilizer wings embossed with swastikas were dropped in order to establish German claims to ownership (which, however, was never raised). During an additional eight special flights, in which Ritscher also took part, particularly interesting regions were filmed and taken with color photos. He flew over an area of about 600.000 km2 (231.661 sq mi). Around 11,600 aerial photographs were taken. Biological investigations were carried out on board the Schwabenland and on the sea ice on the coast. However, the equipment did not allow sled expeditions to the ice shelf or landing of the flying boats in the mountains. All explorations were carried out without a single member of the expedition having entered the territory.[4]

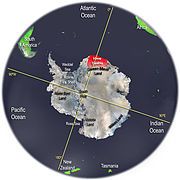

The region between 10 ° W and 15 ° E was named New Swabia (Neuschwabenland) by the expedition leader. In the meantime, the Norwegian government had found out about the German Antarctic activities after the wife of the deputy expedition leader Ernst Herrmann had informed Norwegian geologist Adolf Hoel. On January 14, 1939 the Norwegian government declared the entire sector between 20 ° W and 45 ° E Norwegian territory (Queen Maud Land) without defining its southern extent.[5]

On February 6, 1939 the expedition embarked on its return voyage, left the coast of Antarctica and carried out further oceanographic research in the vicinity of Bouvet Island and Fernando de Noronha. At the request of the Navy High Command, crew members landed on the Brazilian island of Trindade on March 18 to check whether submarines could be supplied with fresh water and food without being noticed. The landing crew was shipwrecked in a small bay and had to be rescued. Since the landing had taken place in the strictest secrecy, Ritscher's did not include it in his final printed report. On April 11, 1939, the Schwabenland arrived at the port of Hamburg.[6]

Geographic features mapped by the expedition

[edit]

As the area was first explored by a German expedition, the name New Swabia and German names given to its geographic features are still used on some maps. Some geographic features mapped by the expedition were not named until the Norwegian-British-Swedish Antarctic Expedition (NBSAE) (1949–1952), led by John Schjelderup Giæver. Others were only named after they were remapped from aerial photos taken by the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition (1958–1959). [7]

- Ahlmann Ridge

- Alan Peak

- Aurdalsegga Ridge

- Austvorren Ridge

- Boreas Nunatak

- Borg Massif

- Cape Sedov

- Conrad Mountains

- Dalsnatten Crag

- Drygalski Mountains

- Dvergen Hill

- Dyna Hill

- Filchner Mountains

- Fjellimellom Valley

- Fimbul Ice Shelf

- Gamaleya Rock

- Gessner Peak

- Gburek Peaks

- Gneiskopf Peak

- Gockel Ridge

- Habermehl Peak

- Herrmann Mountains

- Høghamaren Crag

- Horgebest Peak

- Hortebrekka Slope

- Horteflaket Névé

- Humboldt Mountains

- Isdalen Valley

- Isdalsegga Ridge

- Isfossnipa Peak

- Ising Glacier

- Isingsalen Saddle

- Isingufsa Bluff

- Istind Peak

- Kal'vets Rock

- Knut Rocks

- Kraul Mountains

- Kruber Rock

- Kvamsgavlen Cliff

- Kvitkleven Cirque

- Kvitskarvhalsen Saddle

- Låghamaren Cliff

- Lake Untersee

- Luna-Devyat' Mountain

- Mount Dallmann

- Mount Dobrynin

- Mount Krüger

- Mount Neustruyev

- Mount Zimmermann

- Mount Zuckerhut

- Mühlig-Hofmann Mountains

- New Swabia

- Orvin Mountains

- Payer Mountains

- Penck Trough

- Per Rock

- Petermann Ranges

- Preuschoff Range

- Rømlingsletta Flat

- Rindehallet Slope

- Ritscher Peak

- Ritscher Upland

- Saetet Cirque

- Sandeggtind Peak

- Schirmacher Oasis

- Schirmacher Ponds

- Shatskiy Hill

- Sjøbotnen Cirque

- Skaret Pass

- Skeidskar Gap

- Skimten Hill

- Slithallet Slope

- Sørskeidet Valley

- Stabben Mountain

- Steinbotnen Cirque

- Storeidet Col

- Storkvarvet Mountain

- Storsåtklubben Ridge

- Südliche Petermann Range

- Sverdrup Mountains

- Sverre Peak

- Terningen Peak

- Tindeklypa

- Torgny Peak

- Tysk Pass

- Utrista Rock

- Vestskotet Bluff

- Vorposten Peak

- Weyprecht Mountains

- Wohlthat Mountains

- Zhil'naya Mountain

- Zwiesel Mountain

Scientific evaluation

[edit]Until 1942 Otto von Gruber produced detailed topographical maps of eastern Neuschwabenland at a scale of 1: 50,000 and an overview map of Neuschwabenland. Among the newly discovered areas were, for example, the Kraul Mountains, named after expedition whaler and pilot Otto Kraul. The evaluation of the results in western Neuschwabenland was interrupted by the Second World War and a large part of the 11,600 oblique aerial photographs were lost during the war. In addition to the images and maps published by Ritscher, only about 1100 aerial photos survived the war, but these were only rediscovered and evaluated in 1982. The results of the biological, geophysical and meteorological investigations were only published after the war between 1954 and 1958. Captain Ritscher did in fact prepare another expedition with improved, lighter aircraft on skids, which however was never carried out due to the outbreak of the Second World War.[8][9]

Public perception

[edit]

As a result of great secrecy and relatively little time for preparation, the enterprise completely escaped any advanced public attention as the MS Schwabenland embarked unnoticed.

The first report of the expedition was telegraphed only during the return journey from Cape Town to Helmut Wohlthat, who published a press release on March 6th 1939. As in Great Britain the Daily Telegraph and in the USA the New York Times reported on the expedition in reference to the Norwegian occupation of the area, only the Hamburg local press took notice of the expedition's return to Germany. On May 25, 1939, the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung magazine published a small-scale map of the mountains discovered and the flight polygons without authorization by the expedition leader. The map was drawn by the aircraft mechanic Franz Preuschoff and is as such referred to as the "Preuschoff map". This map was incorporated in the 1939 1: 10,000,000 scale map of Antarctica by Australian cartographer E. P. Bayliss.

A reference to the expedition was posted in the Berlin Zoological Garden in front of the Emperor penguin enclosure. The penguins had been caught by Lufthansa flight captain Rudolf Mayr, flight mechanic Franz Preuschoff and zoologist Erich Barkley and arrived in Cuxhaven on April 12, 1939. The expedition geologist Ernst Herrmann, published the only popular science book for a wider audience for more than 60 years in 1941. Due to the lack of information during the following decades, myths and conspiracy theories eventually developed around the expedition and Neuschwabenland.[10][11]

Aftermath

[edit]Although Germany issued a decree about the establishment of a German Antarctic Sector called New Swabia after the expedition's return in August 1939 no official territorial claims were ever advanced for the region, abandoned in 1945 and never revoked since.[12] No whaling station or other lasting structure was built by Germany until the Georg-von-Neumayer-Station, a research facility, established in 1981. The current Neumayer-Station III is also located in the region.

New Swabia is now a cartographic area of Queen Maud Land which is administered by Norway as a dependent territory under the Antarctic Treaty System by the Polar Affairs Department of the Ministry of Justice and the Police.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ Eric Niiler. "Hitler Sent a Secret Expedition to Antarctica in a Hunt for Margarine Fat". A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ C. P. Summerhayes. "Hitler's Antarctic Base: The Myth and the Reality". University of Cambridge. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ Luke Fater (November 6, 2019). "Hitler's Secret Antarctic Expedition for Whales". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ Cornelia Lüdecke. Germans in the Antarctic. Springer Nature. pp. 155–. ISBN 978-3-030-40924-1.

- ^ Andrew J. Hund (14 October 2014). Antarctica and the Arctic Circle: A Geographic Encyclopedia of the Earth's Polar Regions [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 303–. ISBN 978-1-61069-393-6.

- ^ William James Mills (2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers: M-Z. ABC-CLIO. pp. 552–. ISBN 978-1-57607-422-0.

- ^ USGS GNIS

- ^ Cornelia Lüdecke; Colin Summerhayes (15 December 2012). The Third Reich in Antarctica: the German Antarctic Expedition, 1938-39. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-72091-889-9.

- ^ Deutsche hydrographische Zeitschrift: Ergänzungsheft. Reihe B. Deutsches Hydrographisches Institut. 1980.

- ^ Wilhelm Filchner; Alfred Kling; Erich Przybyllok (1994). To the Sixth Continent: The Second German South Polar Expedition. Bluntisham Books. ISBN 978-1-85297-038-3.

- ^ Rainer F. Buschmann; Lance Nolde (26 July 2018). The World's Oceans: Geography, History, and Environment. ABC-CLIO. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-1-4408-4352-5.

- ^ Heinz Schön, Mythos Neu-Schwabenland. Für Hitler am Südpol, Selent: Bonus, 2004, p. 106, ISBN 978-3935962056, OCLC 907129665

- ^ "Queen Maud Land". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 April 2011.