User:Tim O'Doherty/sandbox/10

2024 Scottish government crisis

[edit]

Humza Yousaf announcing his intention to resign as SNP leader on 29 April 2024 | |

| Date | 25–29 April 2024 |

|---|---|

| Cause |

|

| Motive | To declare no confidence in Humza Yousaf |

| Participants | Conservative, Labour, Green, Liberal Democrat and Alba MSPs |

| Outcome |

|

In April 2024 Humza Yousaf, first minister of Scotland and leader of the Scottish National Party (SNP), faced a confidence crisis following his termination of the Bute House Agreement, a power-sharing agreement between the SNP and the Scottish Greens, which had previously allowed his party to govern.

The agreement was formed following the 2021 Scottish Parliament election in which the SNP, led by Nicola Sturgeon, fell one seat short of an overall majority: it detailed a shared policy programme between the parties, areas of collaboration and disagreement, and Patrick Harvie and Lorna Slater, the co-leaders of the Greens, were appointed ministers. Initially popular with the SNP membership, dissatisfaction grew within the parliamentary party on the agreement and the Greens' position in government; in September 2023 Fergus Ewing was suspended from the party for voting against Slater in a confidence motion. Following the wellbeing economy secretary Màiri McAllan's announcement in April 2024 that the government—then led by Yousaf—were to change key climate change targets the Greens scheduled a vote on whether to remain in the agreement. On 25 April, before the vote was due to take place, Yousaf terminated the agreement and announced his intention to govern as a minority: Harvie and Slater's ministerial posts were abolished and his first government dissolved.

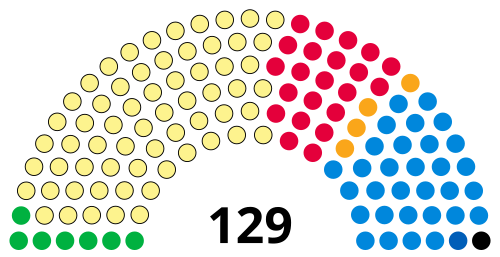

At First Minister's Questions in the afternoon the Scottish Conservatives announced that they would table a vote of no confidence in Yousaf; the following day Scottish Labour said that they would table a different motion, this time in the entire government. The Greens stated that all seven of their MSPs would vote against Yousaf in the Conservative motion: this meant that if all non-SNP MSPs[n 1] voted against Yousaf the vote would be successful. Ash Regan, the sole MSP from the pro-independence Alba Party and who had defected from the SNP the year prior, held the unofficial casting vote: if she backed the government the vote would be tied at 64–64, and the impartial presiding officer would have voted, by convention in favour of the government; if she voted against it, the motion would have been successful at 63–65. Regan sent a list of requests to Yousaf in order to gain her support while he contacted party leaders for talks at Bute House, which were rejected by the Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats and Greens. On 29 April Yousaf announced his resignation, saying he was not willing to trade his principles to remain in power. Following the announcement the Labour motion, scheduled for 1 May, went ahead: it was defeated with the help of Green MSPs.

Background

[edit]Bute House Agreement

[edit]

The Scottish electoral system is designed to make majority government difficult to achieve for any single party.[1] The first election to the Scottish Parliament, held in 1999 following its establishment, resulted in it being hung: Scottish Labour and the Scottish Liberal Democrats formed a coalition, with two Lib Dems becoming cabinet members.[2] The 2003 election saw the Labour–Lib Dem coalition returned, although by a finer margin than before.[3] In 2007 the Scottish National Party (SNP) became the largest party, forming a minority government; this was followed by the party unexpectedly winning an outright majority in 2011,[4] but was reduced to minority status again in 2016.[5]

The 2021 election in May left the SNP, then led by Nicola Sturgeon, on 64 seats: one short of an overall majority.[6] In August, following several months of negotiation, a deal was struck between the government and the similarly pro-independence Scottish Greens. The latter agreed to support the SNP on confidence votes and budgets and the two co-leaders of the Greens—Patrick Harvie and Lorna Slater—were appointed ministers,[n 2] becoming the first Green politicians to enter government in the UK. The parties committed to a shared policy programme, including classifying 10 per cent of sea area in Scotland as Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs), creating 110,000 "affordable" homes, investment in renewable heating, increased focus on public transportation, and the holding of a second independence referendum within five years, following on from the one held in 2014.[8] Areas of collaboration between the SNP and the Greens included issues such as climate change, post-COVID economic recovery, the constitution, child poverty, energy and the environment. The agreement also stipulated policy areas which the Greens were allowed to differ from and criticise the SNP, including on aviation, defence, NATO membership of an independent Scotland, relations with other countries, private education and foxhunting.[9]

In February 2023 Sturgeon announced her resignation as first minister of Scotland and leader of the SNP.[10] Three people declared their intention to stand in the ensuing leadership contest: Humza Yousaf, the health secretary, Ash Regan, a former community safety minister, and Kate Forbes, the finance secretary.[11] During the campaign Forbes and Regan both publicly spoke out in opposition to the agreement,[12] whereas Yousaf supported its continuation.[13] He won the leadership on 27 March, narrowly beating out Forbes after Regan was eliminated on the first round.[14] Following Yousaf's election the Greens decided to stay in the agreement, which would have very likely ended if Forbes or Regan had led the government instead.[15]

Policy friction

[edit]

The co-operation deal was initially popular within the SNP, with around 95 per cent of the party membership voting in favour of it.[16]

Following COP26 in Glasgow Slater announced that the proposed deposit return scheme (DRS) was to be delayed, now being set to be launch in August 2023; in April 2023 Yousaf announced it would be delayed further to March 2024; and following a dispute with the British government over the Internal Market Act 2020 Slater announced in June 2023 it was to be pushed back to October 2025.[17] By July 2023 £86 million had been spent on the scheme.[18] This led the Scottish Conservatives to table a motion of no confidence in Slater on 20 June.[19] The motion failed but Fergus Ewing, an SNP MSP, voted in favour. The parliamentary SNP voted in September to suspend him, which was successful by 48 votes to 9, coming into effect in February 2024.[20] Ewing had been an outspoken critic of the agreement, the SNP leadership and many Green-driven policies. In particular, he attacked the Green plans for HPMAs and the failure of the government to dual the A9, blaming it on Green opposition to roadbuilding.[21] The HMPA policy—which would have banned commercial and recreational fishing in designated areas—was scrapped in June 2023 following anger from fishing communities and organisations over potential job losses and impact on fishers. Forbes, who represents a Highland constituency, warned of the "hugely devastating" effect the scheme would have on the Highlands and Islands; she was joined in her criticism by Alasdair Allan and Karen Adam.[22]

In April Yousaf said a vote for the Greens at the next general election would be a "wasted vote".[23]

In January 2023 the secretary of state for Scotland, Alister Jack, had blocked the Gender Recognition Reform Bill (GRR) from receiving royal assent under section 35 of the Scotland Act 1998 for conflicting with UK-wide legislation. The action was ruled lawful in December following a Scottish government court challenge launched by Yousaf. The bill was controversial within the SNP: in 2022 Regan had resigned from the government in protest at the reforms; seven SNP MSPs voted against the bill in the party's largest ever parliamentary rebellion; and in October the following year Regan defected to the Alba Party in opposition to the SNP's position on gender and attitude towards independence.[24] The Greens, on the other hand, had championed the reforms: during the leadership contest—in which Forbes and Regan were hostile to the plans—Harvie had stated that the Greens would end the agreement if the new leader did not share his party's "progressive values".[25] The Greens urged Yousaf to appeal the ruling, whilst several SNP politicians deemed the bill "politically toxic" and opposed further action.[26] The April 2024 publication of the Cass Review into gender services for children was a further strain on the parties' relationship: the SNP backed the report whilst Harvie refused to accept its findings, with the SNP MSP Michelle Thomson accusing him of "science denialism". The Sandyford clinic in Glasgow paused the prescription of puberty blockers to children after the report's publication, causing the Greens' LGBT wing to question the deal's future. Following the breakup of the agreement, in May the Greens were the only party to vote against a parliamentary motion to endorse the review.[27]

Green vote and termination

[edit]

On 18 April the wellbeing economy, net zero and energy secretary, Màiri McAllan...

[TEXT]. The editor of the journal Scottish Affairs, Michael Rosie, wrote that

Yousaf thus found himself between a rock and a hard place. The agreement was crumbling ... there was discontent in his own party ... it was entirely possible that the Greens would be forced out of the Bute House Agreement by their own grassroots. Yousaf could have waited and allowed the Greens to further undermine the agreement themselves. His hands would have been clean and he would have been less tied into Green agendas. But to wait might have made an already weak first minister look even weaker: indecisive, rudderless.[28]

At 7:00 pm on 24 April Yousaf told his advisers, senior party members and members of his private office that the agreement was to end. At 7:50 am the following day Slater and Harvie arrived for a meeting at Bute House, where they were told of the deal's termination and that they were to be removed as ministers: the pair then left the building and travelled to Parliament without a ministerial car. A cabinet meeting followed at 8:30 am in which government ministers agreed to the decision.[29] At a press conference at 10:00 am Yousaf confirmed the ending of the deal, saying that "the agreement was intended to provide stability to Scottish government, and it has made possible a number of achievements, but it has served its purpose".

Votes of confidence and parliamentary arithmetic

[edit]First Minister's Questions occurs in the Scottish Parliament each Thursday for 45 minutes, beginning at noon.[30]

Resignation

[edit]While a route through this week's vote of no confidence was possible, I am not willing to trade my values and principles or do deals with whomever simply for retaining power. After spending the weekend reflecting ... I've concluded that repairing our relationship across the divide can only be done with someone else at the helm.

At 11:00 pm on 28 April The Times reported that Yousaf was planning to announce his resignation the following day and had informed senior party members of his intentions.[31] The following morning Bute House confirmed that a press conference was to occur at noon and that the first minister would make a statement on his future. As expected Yousaf announced his resignation at the conference.

Aftermath

[edit]

The Conservatives withdrew their motion, with Ross saying that had "achieved its purpose". Labour announced that their motion would still go ahead, which the Greens criticised as unnecessary and "parliamentary game playing". On 1 May it was defeated with the help of Green MSPs; Regan, however, voted in favour of it.

Nominations for the ensuing leadership election opened at 11:59 pm on the 29th and were to close at noon on 6 May.[32] It was expected that Forbes would stand again.[33] John Swinney, Sturgeon's government deputy, said that he was considering a bid when questioned shortly after Yousaf's resignation speech.[34] On 2 May he declared his candidacy in Edinburgh and said that Forbes would be welcomed into a government he would lead;[35] shortly afterwards she announced that she would not stand, endorsing Swinney.[36] Graeme McCormick, an SNP activist, stated on the 5th that he had secured enough nominations from party members to stand, but after talks with Swinney that afternoon he decided that he would not seek the leadership. With no other candidates declaring, Swinney was announced as leader shortly after noon the following day.

Yousaf tendered his resignation to the King on 7 May. Swinney became Parliament's nominee for first minister that afternoon with 64 votes: 63 SNP MSPs plus Regan. The Greens abstained, with Slater saying that the government did not have an "automatic right to our votes". He was sworn in as first minister on the 8th at the Court of Session. His minority government remained largely unchanged from Yousaf's: Forbes was given the role of deputy first minister as well as responsibility for the economy and the Gaelic language; Shona Robison—Yousaf's deputy—retained her role as finance secretary with increased responsibility for local government; McAllan kept her position but lost responsibility of the economy; the position of minister for independence, created by Yousaf, was abolished; and the number of junior ministerial positions was slightly reduced. The appointment of Forbes as Swinney's deputy was seen as a move to the political centre, given her more socially conservative religious views: following the announcement of the new cabinet Harvie tweeted an image of a "no right turn" road sign and a Green member told The Scotsman that "if the SNP moves too far to the right, they will need to look elsewhere to get their policies and budgets passed. We are not here to simply endorse an SNP minority government".[37]

See also

[edit]- Vaughan Gething, Welsh first minister who lost a confidence motion one month after Yousaf resigned[38]

- Henry McLeish, Scottish first minister who resigned shortly before a confidence motion in him[39]

References and notes

[edit]Notes

- ^ Barring the presiding officer, who is impartial

- ^ Harvie: Minister for Zero Carbon Buildings, Active Travel and Tenants' Rights

Slater: Minister for Green Skills, Circular Economy and Biodiversity[7]

References

- ^ Denver & MacAllister 1999, p. 11; Johns, Mitchell & Carman 2013, p. 158.

- ^ Denver & MacAllister 1999, p. 12; Lynch 2001, pp. 29–33.

- ^ Denver 2003, pp. 32–33.

- ^ McCrone 2009, p. xi; Johns, Mitchell & Carman 2013, pp. 158 and 163.

- ^ Cairney 2016, p. 278.

- ^ MacMillan & Henderson 2021, p. 38.

- ^ "Programme for Government 2023 to 2024". gov.scot, p. 52.

- ^ "Agreement with Scottish Green Party". gov.scot; Morris 2021.

- ^ Bennie 2023, p. 4; Mitchell 2023, p. 275.

- ^ Rosie 2023, p. 389.

- ^ Bennie 2023, p. 5; Cochrane 2024.

- ^ Mitchell 2023, p. 280.

- ^ Bennie 2023, p. 5; Mitchell 2023, pp. 276, 283–284; Hassan 2023, p. 561.

- ^ Bennie 2023, p. 6; Mitchell 2023, p. 285.

- ^ Andrews 2023; Pooran 2023.

- ^ Watson 2023; Rosie 2023, pp. 391–392; "Scottish deposit return delayed until October 2025". BBC News.

- ^ Johnson 2023b.

- ^ "Tories table vote of no confidence in Lorna Slater". BBC News.

- ^ Rosie 2023, p. 392; Brooks 2024b.

- ^ Bol 2023; Brooks 2024b; Cochrane 2023; "Delayed dualling of A9 is costing lives, says Fergus Ewing". BBC News.

- ^ Cochrane 2023; Bol 2023; Boothman 2023.

- ^ McCurdy 2024; Carrell & Brooks 2024.

- ^ "SNP minister Ash Regan resigns over gender recognition plans". BBC News; "Block on Scottish gender reforms to be challenged in court". BBC News; Rosie 2023, p. 390; Gordon 2023; Brooks 2024a.

- ^ Rosie 2023, p. 389; Boothman 2023; Roberts & Williams 2023.

- ^ Gordon 2023; Johnson 2023a.

- ^ Rosie 2024, pp. 267–268; Andrews 2024c; Sanderson 2024; "Humza Yousaf says he 'paid price' for upsetting Greens". BBC News; McCool 2024.

- ^ Rosie 2024, p. 268.

- ^ Andrews & Boothman 2024; McDonald 2024; Carrell 2024.

- ^ "About questions and answers". parliament.scot.

- ^ McDonald 2024; Andrews 2024a.

- ^ Harness & Esson 2024.

- ^ Andrews 2024b.

- ^ Butler 2024.

- ^ Mitchell 2024.

- ^ Maidment & Johnson 2024.

- ^ Rosie 2024, p. 269.

- ^ Hale, Cassidy & Deans 2024.

- ^ Seenan & Scott 2001.

Sources

[edit]Books and journals

[edit]- Bennie, Lynn (June 2023). "A Critical Time for the SNP: A New Leader and 'First Activist'". Political Insight. 14 (2): 4–8. doi:10.1177/20419058231181276a.

- Cairney, Paul (August 2016). "The Scottish Parliament Election 2016: Another Momentous Event but Dull Campaign". Scottish Affairs. 25 (3): 277–293. doi:10.3366/scot.2016.0136.

- Denver, David (August 2003). "A 'Wake Up!' Call to the Parties? The Results of the Scottish Parliament Elections 2003". Scottish Affairs. 44: 31–53. eISSN 2053-888X.

- Denver, David; MacAllister, Iain (June 1999). "The Scottish Parliament Elections 1999: an Analysis of the Results". Scottish Affairs. 28: 10–31. eISSN 2053-888X.

- Hassan, Gerry (26 October 2023). "From Donald Dewar to Humza Yousaf: The Role of Scotland's First Ministers and the Importance of Political Leadership". The Political Quarterly. 94 (4): 556–564. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.13333.

- Johns, Robert; Mitchell, James; Carman, Christopher J. (April 2013). "Constitution or competence? The SNP's re-election in 2011". Policy Studies. 61 (1): 158–178. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12016.

- Lynch, Peter (2001). Scottish Government and Politics: An Introduction. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1287-4.

- MacMillan, Fraser; Henderson, Aisla (September 2021). "Scotland's Future? The 2021 Holyrood Election". Political Insight. 12 (3): 37–39. doi:10.1177/20419058211045147.

- McCrone, David (2009). Revolution or Evolution?: The 2007 Scottish Elections. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748642151.

- Mitchell, James (August 2023). "From Team Nicola to Team Humza: the SNP Leadership Contest 2023 in Perspective". Scottish Affairs. 32 (3): 263–289. doi:10.3366/scot.2023.0464.

- Rosie, Michael (November 2023). "After the Fall...". Scottish Affairs. 32 (4): 387–396. doi:10.3366/scot.2023.0472.

- Rosie, Michael (August 2024). "All Change. Again". Scottish Affairs. 33 (3): 263–272. doi:10.3366/scot.2024.0508.

Online news articles

[edit]- Andrews, Kieran (28 April 2024a). "Humza Yousaf set to resign as survival hopes fade". The Times. Archived from the original on 29 April 2024. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- Andrews, Kieran (30 April 2024b). "Kate Forbes signals bid to become first minister". The Times. Archived from the original on 2 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- Andrews, Kieran (22 April 2024c). "Patrick Harvie will not accept Cass review on gender identity". The Times. Archived from the original on 21 June 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- Andrews, Kieran (3 April 2023). "Third of SNP voters want an end to Green power-sharing deal". The Times. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- "Block on Scottish gender reforms to be challenged in court". BBC News. 12 April 2023. Archived from the original on 18 December 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- Bol, David (29 December 2023). "Scottish Greens: A year of coalition friction and binned policies". The Herald. Archived from the original on 8 January 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- Bonar, Megan; Cook, James (25 April 2024). "Scottish Greens to vote on SNP power-sharing deal". BBC News. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- Boothman, John (29 May 2023). "The six Green Party policies tearing the SNP apart". The Times. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- Brooks, Libby (29 April 2024a). "Humza Yousaf inherited a deeply fractured SNP – as will his successor". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 May 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- Brooks, Libby (28 February 2024b). "SNP's Fergus Ewing urges party to ditch Greens pact as suspension confirmed". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 April 2024. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- Butler, Alexander (29 April 2024). "Former SNP leader John Swinney mulls bid to become Scotland's next first minister". The Independent. Archived from the original on 29 April 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- Carrell, Severin; Brooks, Libby (25 April 2024). "What was the SNP and Greens' deal and what happens now it has ended?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 May 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- Carrell, Severin (25 April 2024). "Humza Yousaf in peril as Greens say they will back no confidence motion". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 April 2024. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- Cochrane, Angus (2 May 2024). "Who is Kate Forbes, potential SNP leader?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 May 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- Cochrane, Angus (29 June 2023). "Why are Highly Protected Marine Areas so controversial?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 April 2024. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- "Delayed dualling of A9 is costing lives, says Fergus Ewing". BBC News. 30 May 2023. Archived from the original on 26 April 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- Gordon, Tom (9 December 2023). "Yousaf faces clash with Greens amid SNP calls to ditch gender Bill". The Herald. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- Hale, Adam; Cassidy, Maria; Deans, David, eds. (5 June 2024). "Wales' first minister Gething loses vote of no confidence". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 June 2024. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- Harness, James; Esson, Graeme, eds. (30 April 2024). "Forbes 'considering options' over SNP leadership bid". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- "Humza Yousaf says he 'paid price' for upsetting Greens". BBC News. 1 May 2024. Archived from the original on 23 May 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- Johnson, Simon (11 December 2023a). "Humza Yousaf should not be 'bullied' into appealing Self-ID Gender Laws". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- Johnson, Simon (30 July 2023b). "SNP's failed bottle deposit scheme has cost £186m [sic] and taxpayers could bear brunt". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- Maidment, Jack; Johnson, Simon, eds. (2 May 2024). "Kate Forbes pulls out of SNP leadership race". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- McCool, Mary (18 April 2024). "Scotland's under-18s gender clinic pauses puberty blockers". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- McCurdy, Rebecca (9 April 2024). "Yousaf: Voting Greens would be a 'wasted vote' despite Holyrood partnership". The Independent. Archived from the original on 16 April 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- McDonald, Andrew (30 April 2024). "How Humza Yousaf blew up his leadership in 5 days". Politico. Archived from the original on 3 May 2024. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- Mitchell, Jenness (2 May 2024). "SNP leadership race: John Swinney announces bid to succeed Humza Yousaf as Scotland's first minister". Sky News. Archived from the original on 2 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- Morris, Sophie (20 August 2021). "Scotland: SNP and Scottish Greens' power-sharing agreement is 'groundbreaking', Nicola Sturgeon says". Sky News. Archived from the original on 21 September 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- Pooran, Neil (6 December 2023). "SNP must end powersharing deal with Greens, says ex-leadership hopeful Forbes". The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 May 2024. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- Roberts, Georgia; Williams, Craig (20 December 2023). "Healthcare to be improved for trans people - Shona Robison". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 May 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- Sanderson, Daniel (8 May 2024). "Scottish Greens out in cold as only party to vote against Cass Review". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- "Scottish deposit return delayed until October 2025". BBC News. 7 June 2023. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- Seenan, Gerard; Scott, Kirsty (9 November 2001). "Scotland's McLeish quits in money row". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- "SNP-Greens deal pledges indyref2 within five years". BBC News. 20 August 2021. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- "SNP minister Ash Regan resigns over gender recognition plans". BBC News. 27 October 2022. Archived from the original on 1 May 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- "Tories table vote of no confidence in Lorna Slater". BBC News. 20 June 2023. Archived from the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- Watson, Calum (7 June 2023). "Why has Scotland's deposit return scheme been delayed?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 April 2024. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

Offline news sources

[edit]- Andrews, Kieran; Boothman, John (26 April 2024). "Gallows humour as the Greens waited for fate to be sealed". The Times. pp. 6–7.

Websites and other

[edit]- "About questions and answers". parliament.scot. 2024. Archived from the original on 3 May 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- "Agreement with Scottish Green Party". gov.scot. 20 August 2021. Archived from the original on 1 May 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- "Programme for Government 2023 to 2024" (PDF). gov.scot. September 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- "Scottish Government and Scottish Green Party Shared Policy Programme" (PDF). gov.scot. August 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

2024 Welsh government crisis

[edit] Vaughan Gething with the prime minister, Keir Starmer, on 8 July | |

| Date | 17 May – 16 July 2024 |

|---|---|

| Cause |

|

| Motive | To declare no confidence in Vaughan Gething |

| Participants | Andrew RT Davies Rhun ap Iorwerth Hannah Blythyn Lee Waters Mick Antoniw Julie James Lesley Griffiths Jeremy Miles |

| Outcome |

|

Background

[edit]Welsh Labour–Plaid Cymru agreement

[edit]

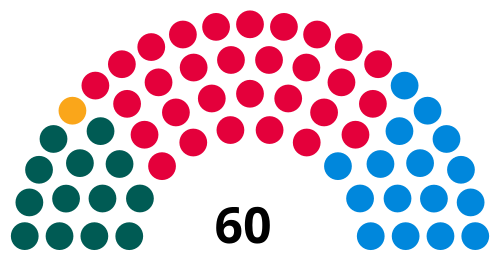

Elections to the Senedd,[n 1] similarly to its Scottish counterpart, use a system which makes it difficult for any party to achieve an overall majority of seats, meaning governments often form coalitions, deal with other parties or govern in minority.[2] In the post-war era the Labour Party had traditionally dominated Welsh politics[3] and despite the devolved electoral system were widely anticipated to win a majority upon the parliament's establishment. In the first National Assembly election, however, Labour fell short of the required 31 seats because of a surge in support for the nationalist Plaid Cymru; this was termed a daergryn tawel ("quiet earthquake") by the leader of the latter, Dafydd Wigley.[4] At the following election in 2003 Plaid lost five of its seats and Labour (now Welsh Labour) increased its tally to 30: half of the chamber, and decided to govern as a minority, ending the coalition with the Liberal Democrats formed in 2000.[5] 2007 saw Labour drop to 26 seats with an increase in Plaid support, and, following failed negotiations for a rainbow coalition with Plaid, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats, a coalition government was agreed between Labour and Plaid.[6] In 2011 Labour returned 30 seats and once again governed alone.[7] The party dropped one seat in 2016; Labour formed a government with the remaining Liberal Democrat assembly member and a former Plaid leader who had decided to sit as an independent.[8]

In the 2021 Senedd election Labour increased its seat count by one—winning 30 seats—performing more strongly than the opinion polls had predicted;[9] this was attributed by analysts in part to the handling of the pandemic by the first minister, Mark Drakeford.[10] The result was described by several academics as "disappointing" for Plaid and the Liberal Democrats, with the former's vote share almost unchanged and the latter having lost its sole constituency, only managing to take the last of the list seats in the Mid and West region, having, in the political scientist Roger Awan-Scully's phrase, "clung onto political life".[11]

First 2024 leadership election

[edit]

Gething premiership

[edit]

Withdrawal of Plaid

[edit]

Vote of no confidence

[edit]Events in July; resignation

[edit]Aftermath

[edit]

See also

[edit]References and notes

[edit]Notes

References

Sources

[edit]- ^ Awan-Scully 2021, p. 469; Larner et al. 2022, p. 857.

- ^ Greer 2019, pp. 553–554; Larner et al. 2022, p. 863.

- ^ Jones & Awan-Scully 2006, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Trystan, Awan-Scully & Jones 2003, p. 636; Jones & Awan-Scully 2006, p. 179.

- ^ McAllister 2004, pp. 74–76.

- ^ McAllister & Cole 2007, pp. 539–540, 543.

- ^ McAllister & Cole 2011, p. 176.

- ^ Awan-Scully & Larner 2016, pp. 518–519; Larner et al. 2022, p. 867.

- ^ Awan-Scully 2021, pp. 472–473; Larner et al. 2022, pp. 859–860, 863 and 868.

- ^ Awan-Scully 2021, p. 471; Larner et al. 2022, pp. 861–863, 871 and 873.

- ^ Awan-Scully 2021, p. 472; Larner et al. 2022, pp. 864–865.

Books and journals

[edit]- Awan-Scully, Roger (6 August 2021). "Unprecedented Times, a Very Precedented Result: the 2021 Senedd Election". The Political Quarterly. 92 (3): 469–473. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.13045.

- Awan-Scully, Roger; Larner, Jac (3 December 2016). "A Successful Defence: the 2016 National Assembly for Wales Election". Parliamentary Affairs. 70 (3): 507–529. doi:10.1093/pa/gsw033.

- Greer, Alan (14 June 2019). "Reflections on Devolution: Twenty Years on". The Political Quarterly. 90 (3): 553–558. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.12700.

- Jones, Richard Wyn; Awan-Scully, Roger (2006). "Devolution and electoral politics in Wales". In Hough, Dan; Jeffery, Charlie (eds.). Devolution and electoral politics. Manchester University Press. pp. 176–191. ISBN 978-0719073304.

- Larner, Jac; Jones, Richard Wyn; Poole, Ed Gareth; Surridge, Paula; Wincott, Daniel (10 May 2022). "Incumbency and Identity: The 2021 Senedd Election". Parliamentary Affairs. 76 (4): 857–878. doi:10.1093/pa/gsac012.

- McAllister, Laura (2004). "Steady State or Second Order? The 2003 Elections to the National Assembly for Wales". The Political Quarterly. 75 (1): 73–82. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.2004.00573.x.

- McAllister, Laura; Cole, Michael (2007). "Pioneering New Politics or Rearranging the Deckchairs? The 2007 National Assembly for Wales Election and Results". The Political Quarterly. 78 (4): 536–546. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.2007.00888.x.

- McAllister, Laura; Cole, Michael (10 July 2012). "The 2011 Welsh General Election: An Analysis of the Latest Staging Post in the Maturing of Welsh Politics". Parliamentary Affairs. 67 (1): 172–190. doi:10.1093/pa/gss036.

- Trystan, Dafydd; Awan-Scully, Roger; Jones, Richard Wyn (2003). "Explaining the 'quiet earthquake': voting behaviour in the first election to the National Assembly for Wales". Electoral Studies. 22: 635–650. doi:10.1016/S0261-3794(02)00028-8.