User:TentingZones1/Random list

Chichewa Tones 1

[edit]1st example

[edit]The accompanying illustration from Myers[1] shows the typical intonation of a declarative statement in Chichewa:

- mwamúna, á-ma-lamúla amáyi 'a man, he rules women'

The four high tones, marked H on the transcription, come down in a series of steps, a process common in many languages and known as downdrift, automatic downstep, or catathesis. This tends to occur (with some exceptions) whenever two high tones are separated by one or more intervening low tones; it does not occur when two high tones come in adjacent syllables.

Also illustrated in the pitch track is an intonational tone, known as a boundary tone, or 'continuation rise',[2] marked L%H%. This rise in pitch is typically heard at any pause in the middle of a sentence, such as here, where it marks the topic: 'a man, he rules women'. The boundary tone is not obligatory, and Myers prints another pitch track of the same sentence where it is absent.

The toneless syllables tend to be lower than the high-toned syllables. However, the first syllable of amáyi anticipates the following high tone and is almost on the same level. The last syllable of á-ma-lamúla is also raised. This tonal spread from a penultimate high tone is frequently heard when a verb is immediately followed by its grammatical object. The first three syllables of á-ma-lamúla also show a glide downwards, with ma higher than la.

The penultimate tones of mwamúna 'a man' and amáyi 'women' are lexical tones, meaning that they always occur in these words. The tones of ámalamúla 'he rules' are grammatical tones, which are always found in the Present Habitual tense. The verb stem itself (lamula 'rule') is toneless.

2nd example

[edit]The second illustration[3] shows the pitch-track of the following sentence:

- anádyétsa nyaní nsómba 'they fed the baboon (some) fish'

The sentence has a grammatical tone on the Remote Perfect tense anádyetsa 'they fed' and lexical tones on nyaní 'baboon' and nsómba 'fish'.

In this example, in the word anádyetsa the peak (high point) of the accent does not coincide with the syllable but is delayed, giving the impression that it has spread to two syllables. This process is known as 'tone doubling' or 'peak delay', and is typical of speakers in some regions of Malawi.

The second word, nyaní 'baboon', has an accent on the final syllable, but as usually happens with final accents, it spreads backwards to the penultimate syllable, showing a nearly level or gently rising contour, with only the initial n being low-pitched. Another feature of a final accent is that it tends not to be very high.[4] In this case it is actually slightly lower than the high tone of nsómba which follows it.

When a final-tone word such as nyaní comes at the end of a sentence, it is often pronounced as nyăni with a rising tone on the penultimate and the final syllable low. But if a suffix is added, the stress moves to the new penultimate, and the word is pronounced with a full-height tone on the final: nyaní-yo 'that baboon'.[5]

The third word, nsómba 'fish', has penultimate accent. Since the word ends the sentence, the tone falls from high to low.

As with the previous illustration, there is downdrift from the first tone to the second. But when two tones come in adjacent syllables, as in nyaní nsómba, there is no downdrift.

The intensity reading at the top of the voice track shows that the intensity (loudness) is greatest on the penultimate syllable of each word.

Chichewa Tones 2

[edit]Lexical tones

[edit]Nouns

[edit]Certain syllables in Chichewa words are associated with high pitch. Usually there is one high pitch per word or morpheme, but some words have no high tone. In nouns the high pitch is usually in one of the last three syllables:[6]

- chímanga 'maize'

- chikóndi 'love'

- chinangwá 'cassava'

In a few nouns (often compound words) there are two high tones. If these tones are separated by only one unaccented syllable, they usually join in a plateau of three high-toned syllables; that is, HLH becomes HHH. Similarly the first tone of words ending HLLH can spread to make HHLH:

- bírímánkhwe 'chameleon'

- tsábólá 'pepper'

- chizólówezí / chizólowezí 'habit'

In addition there are a large number of nouns which have no high tone, but which, even when focussed or emphasised, are pronounced with all the syllables low:

- chipatala 'hospital'

- mkaka 'milk'

- nyama 'animal'

A tonal accent differs from a stress-accent in languages such as in English in that it always retains the same pitch contour (e.g. high-low, never low-high). It is also possible for a high tone to contrast with a low tone:

- mténgo 'tree'

- mtengo 'price'

High-toned verbs

[edit]Most verbal roots in Chichewa, including all monosyllabic verbs, are toneless, as the following:

- thandiza 'help'

- pita 'go'

- -dya 'eat'

- -fa 'die'

A few verbal roots, however, have a lexical tone, which is heard on the final vowel -a of the verb:

- thamangá 'run'

- thokozá 'thank'

The tones are not inherited from proto-Bantu, and do not correspond to the high-low distinction of verbal roots in other Bantu languages, but appear to be an independent development in Chichewa.[7]

Often a verb has a tone not because the root itself has one but because a stative or intensive extension is added to it:

- dziwa 'know'

- dziwiká 'be known'

- funa 'want'

- funitsitsá 'want very much'

When an extension, whether a high-toned or low-toned, is added to a high-toned verb, only one tone is heard, on the final:

- pezá 'find'

- pezererá 'catch someone in the act'

- thamangirá 'run after'

Grammatical tones

[edit]Tonal patterns of tenses

[edit]In addition to the lexical tones described above, Chichewa verbs also have grammatical tones. Each tense conforms to a particular tonal melody, which is the same for every verb in that tense (with adjustments made depending on the length of verb). For example, the following tenses have a high tone immediately after the tense-marker:

- ndi-ku-thándiza 'I am helping'

- ndi-ma-thándiza 'I was helping'

- ndi-na-thándiza 'I helped (just now)'

The following have two separate tones, one on the tense-marker and one on the penultimate syllable:

- ndi-nká-thandíza 'I used to help'

- ndi-zí-thandíza 'I should be helping'

- ndi-ka-má-thandíza 'if ever I help'

The following tenses are toneless:

- nd-a-thandiza 'I have helped'

- ndi-nga-thandize 'I can help'

- ndi-ka-thandiza 'if I help'

and so on. There are at least eight different tonal patterns in affirmative verbs, in addition to further patterns used in negative tenses and in relative clause verbs.[8]

Adding an object-marker

[edit]The tonal pattern frequently changes again when other morphemes such as aspect-markers or an object-marker are added to the verb. For example:

- ndi-ku-thándiza 'I am helping'

- ndi-ku-mú-thandizá 'I am helping him'

- sí-ndí-má-thandiza 'I never help him'

- sí-ndí-má-mu-thandíza 'I never help him'

In other tenses, however, notably those with penultimate tone, the object-marker loses its tone and the tense pattern remains unchanged:

- ndí-ma-thandíza 'I usually help'

- ndí-ma-mu-thandíza 'I don't help him'

- si-ndi-thandíza 'I won't help'

- si-ndi-mu-thandíza 'I won't help him'

Negative tense patterns

[edit]Negative verbs usually have different tonal patterns from the same tense when positive, and sometimes there are two different negative patterns, according to the meaning, for example:

- sí-ndí-thandiza 'I don't help'

- si-ndi-thandíza 'I won't help'

- sí-ndí-na-thandíze 'I didn't help'

- si-ndi-na-thandíze 'I haven't helped yet'

Dependent clause patterns

[edit]In several tenses the tonal pattern changes when the verb is used in a relative, temporal, or conditional clause. Sometimes a change in tonal pattern alone is sufficient to show that a verb is being used in this way. The principal change is that a tone is added on the first syllable of the verb, and there is often one on the penultimate as well:

- chaká chatha 'the year has ended'

- chaká chátha 'the year which has ended (i.e. last year)'

- ali ku Lilongwe 'he is in Lilongwe'

- álí ku Lilongwe 'when he is/was in Lilongwe'

- ndi-ka-dá-thandiza 'I would have helped'

- ndí-ka-da-thandíza 'if I had helped'

Lexical tone combined with tonal pattern

[edit]When the verb-root itself has a high tone, this tone can be heard on the final syllable in addition to the tonal pattern:

- ndi-ka-dá-thandiza 'I would have helped'

- ndi-ka-dá-thamangá 'I would have run' (lexical tone can be heard)

However, if the tonal pattern of the tense places a tone on the penultimate or final syllable, the lexical tone is neutralised and cannot be heard.

- si-ndi-thandíza 'I won't help'

- si-ndi-thamánga 'I won't run' (lexical tone deleted)

- ndi-thandizé 'I should help'

- ndi-thamangé 'I should run'

If a tonal pattern places a tone on the antepenultimate syllable of a high-toned verb, the two tones join into a plateau:

- ndi-ku-thámángá 'I am running'

- nd-a-mú-pézá 'I have found him'

Intonational tones

[edit]Lexical and grammatical tones are not the only tones heard in a Chichewa sentence, but there are intonational tones as well. One common tone is a boundary tone rising from low to high which is heard whenever there is a pause in the sentence, for example after a topic or subordinate clause.

Tones are also added to questions. For example, the toneless word kuti 'where?' becomes kúti in the following question:

- kwánu ndi kúti? 'where is your home?'

Further details of intonational tones are given below.

Chichewa Tones 3

[edit]In order to understand Chichewa tones, it is necessary first to understand various tonal phenomena that can occur, which are briefly outlined below.

Downdrift

[edit]Normally in a Chichewa sentence, whenever two high tones are separated by one or more toneless syllables (i.e. when the tones come in the sequence HLH or HLLH or HLLLH), it is usual for the second high tone to be a little lower than the first one. So for example in the word á-ma-lamúla 'he usually rules' in the example illustrated above, the tone of the first syllable á is pronounced a little higher than the tone of the second tone mú. Thus generally speaking the highest tone in a sentence is the first one. This phenomenon, which is common in many Bantu languages, is known as 'downdrift'[9] or 'catathesis'[10] or 'automatic downstep'.[11]

However, there are several exceptions to this rule. Downdrift does not occur, for example, when a speaker is asking a question,[12] or reciting a list of items with a pause after each one, or sometimes if a word is pronounced on a high pitch for emphasis. There is also no downdrift in words like wápólísi 'policeman' (derived from wá 'a person of' + polísi 'the police'), where two high tones in the sequence HLH are bridged to make a plateau HHH (see below).

High tone spreading (HTS)

[edit]In some dialects a high tone may sometimes spread to the following syllable; this is known as 'High Tone Spreading' or 'Tone Doubling'.[13] So where some speakers say ndináthandiza 'I helped', others will say ndináthándiza.[14] Some phoneticians argue that what happens here, in some cases at least, is that the highest part or 'peak' of the tone moves forward, giving the impression that the tone covers two syllables, a process called 'peak delay'.[15] An illustration of peak delay can be seen clearly in the pitch-track of the word anádyetsa 'they fed' reproduced above, here pronounced anádyétsa, in Downing et al. (2004).

There are some verb forms where tone-doubling does not occur, for example, in the Present habitual tense, where there is always a low tone on the second syllable:[16]

- ámalamúla 'they usually rule'

In order for HTS to occur, there must be at least 3 syllables following the tone, although not necessarily in the same word. Thus the first tone may spread in the second of each pair below, but not in the first:[17]

- zíkomo 'thank you'

- zíkómo kwámbíri 'thank you very much'

- tambala 'cock, rooster'

- mtengo wá támbala 'the price of a rooster'

One frequent use of tone doubling is to link together two words into a single phrase. This most commonly occurs from the penultimate syllable, but in some dialects also from the antepenultimate. So, for example, when a verb is followed by an object:

- akusáka 'they are hunting'

- akusáká mkángo 'they are hunting a lion'[18]

- kuphíka 'to cook'

- kuphíká nyama 'to cook meat'[19]

- kusámala 'to care for'

- kusámála mkázi 'to care for a wife'[20]

This phenomenon can be seen in the pitch track of the sentence mwamúna, ámalamúla amáyi illustrated at the beginning of this article, in which the tone of -mú- is extended to make ámalamúlá amáyi.

Tone doubling is also found when a noun is followed by a demonstrative or possessive pronoun:

- mikángo 'lions'

- mikángó iyo 'those lions'[21]

- chímanga 'maize'

- chímánga chánga 'my maize'[22]

Tonal plateau

[edit]It sometimes happens that the sequence HLH in Chichewa becomes HHH, making a tonal 'plateau'. A tonal plateau is common after the proclitic words á 'of' and ndí 'and', 'with':[23]

- wápólísi 'policeman' (from wá '(a person) of' and polísi 'police')

- chákúdyá 'food' (from chá '(a thing) of' and kudyá 'to eat')

- ndí Máláwi 'and Malawi'

Before a pause the final tone may drop but the tone of the middle syllable remains high: chákúdya. Sometimes a succession of tones is bridged in this way, e.g. gúlewámkúlu 'masked dancer', with one long continuous high tone from gú to kú.[24]

Another place where a plateau is commonly found is after the initial high tone of dependent clause verbs such as the following:

- ákúthándiza 'when he is helping'; 'who is helping'

- ndítáthándiza 'after I helped'

At the end of words, if the tones are HLH, a plateau is common:

- mkámwíní 'son-in-law'

- atsámúndá 'colonialists' (lit. 'owners of farmland')

- kusíyáná 'difference'

- kulémérá 'weight, being heavy'

However, there are exceptions; for example, in the word nyényezí 'star' the two tones are kept separate, so that the word is pronounced nyényēzī (where ī represents a slightly lower tone than í).[25]

There are also certain tonal tense patterns (such as affirmative patterns 5 and 6 described below) where the two tones are kept separate even when the sequence is HLH:

- ndi-nká-thandíza 'I was helping' (tone pattern 5)

- ndí-ma-dyá 'I usually eat' (tone pattern 6)

No tonal plateau is possible when the underlying sequence of tones is HLLH, even when by spreading this becomes HHLH:

- chizólówezí 'habit'

Tone-shifting ('bumping')

[edit]When a word or closely connected phrase ends in HHL or HLHL, there is a tendency in Chichewa for the second H to move to the final syllable of the word. This process is known as 'tone shifting'[26] or 'bumping'.[27] There are two types in which the second tone moves forward, local and non-local bumping. There is also reverse bumping, where the first tone moves backwards.

Local bumping

[edit]In 'local bumping' or 'local tone shift', LHHL at the end of a word or phrase becomes LHHH, where the two tones are joined into a plateau. This can happen when a final-tone word is followed by a possessive adjective, and also with the words ína 'other' and yénse/ónse 'all':[28]

- nyumbá + yánga > nyumbá yángá 'my house'

- nyumbá + ína > nyumbá íná 'another house'

- nyumbá + zónse > nyumbá zónsé 'all the houses'

In three-syllable words where HHL is due to the addition of an enclitic suffix such as -nso 'also, again', -di 'indeed' or -be 'still', the tones similarly change to HHH:[29]

- nsómbá-nso > nsómbá-nsó 'fish also'

- a-ku-pítá-di > a-ku-pítá-dí 'he is indeed going'

- a-ku-pítá-be > a-ku-pítá-bé 'he is still going'

Tone shift also happens in verbs when the verb would otherwise end with LHHL:[30]

- a-ná-mú-pha > aná-mú-phá 'they killed him'

At the end of a sentence the final high tone may drop again, reverting the word to a-ná-mú-pha.

In pattern 5 and negative pattern 3a verbs (see below) there is a choice between making a plateau and treating the final tone as separate:[31]

- ndi-zí-píta > ndi-zí-pítá / ndi-zí-pitá 'I should be going'

- si-ndi-ngá-ménye > si-ndi-ngá-ményé / si-ndi-ngá-menyé 'I can't hit'

There is no bumping in HHL words where the first syllable is derived from á 'of':

- kwá-mbíri 'very much'

- wá-ntchíto 'worker'

Non-local bumping

[edit]In another kind of tone-shift (called 'non-local bumping'), HLHL at the end of a word or phrase changes to HLLH or, with spreading of the first high tone, HHLH:

- mbúzi yánga > mbúzí yangá / mbúzi yangá) 'my goat'

- bánja lónse > bánjá lonsé 'the whole family'

- chi-módzi-módzi > chi-módzi-modzí / chi-módzí-modzí 'in the same way'

But there is no bumping in tense-patterns 5 and 6 or negative pattern 3 when the tones at the end of the word are HLHL:

- ndí-ma-píta 'I usually go'

- si-ndi-ngá-thandíze 'I can't help'

Reverse bumping

[edit]A related phenomenon, but in reverse, is found when the addition of the suffix -tú 'really' causes a normally word-final tone to move back one syllable, so that LHH at the end of a word becomes HLH:

- ndipité 'I should go' > ndipíte-tú 'really I should go'

- chifukwá 'because' > chifúkwa-tú 'because in fact'

Enclitic suffixes

[edit]Certain suffixes, known as enclitics, add a high tone to the last syllable of the word to which they are joined. When added to a toneless word or a word ending in LL, this high tone can easily be heard:

- Lilongwe > Lilongwé-nso 'Lilongwe also':

Bumping does not occur when an enclitic is added to a word ending HLL:

- a-ku-thándiza 'he is helping' > a-ku-thándizá-be 'he's still helping'

But when an enclitic is combined with word which ends HL, there is local bumping, and the result is a plateau of three tones:

- nsómba 'fish' > nsómbá-nsó 'the fish also'

When added to a word with final high tone, it raises the tone higher (in Central Region dialects, the rising tone on the first syllable of a word like nyŭmbá also disappears):[32]

- nyŭmbá > nyumbá-nso 'the house also'

Not all suffixes are tonally enclitic in this way. For example, when added to nouns or pronouns, the locative suffixes -ko, -ku, -po, -pa, -mo, -mu do not add a tone:

- ku Lilongwe-ko 'there in Lilongwe'

- paméne-pa 'on this spot here'

- m'bókosi-mu 'inside this box'

However, when added to verbs, these same suffixes add an enclitic tone:

- w-a-choká-po 'he's not at home' (lit. 'he has gone away just now')

- nd-a-oná-mo 'I have seen inside it'

Proclitic prefixes

[edit]Conversely, certain prefixes place a high tone on the syllable which follows them. Prefixes of this kind are called 'proclitic'[18] or 'post-accenting'. For example, the prefix ku- of the infinitive puts a tone on the syllable following:

- ku-thándiza 'to help'

Other tenses of this type are described under affirmative tense patterns 4 and 8 below.

Object-markers such as -ndí- 'me' or -mú- 'him/her' etc. also become proclitic when added to an imperative or subjunctive. In a four or five-syllable verb, the tone of the object-marker is heard at the beginning of the verb and may spread:[33]

- mu-ndi-fótókozeré 'please explain to me'

In a three-syllable verb, the tones make a plateau:

- ndi-thándízé-ni! 'help me!'

- mu-ndi-thándízé 'could you help me?'

In a two-syllable verb, the second tone is lost:

- mu-gwíre-ni! 'catch him!'

But in a one-syllable verb, the first tone remains on the object-marker and the second tone is lost:

- ti-mú-phe! 'let's kill him!'

Tone deletion (Meeussen's Rule)

[edit]Meeussen's Rule is a process in several Bantu languages whereby a sequence HH becomes HL. This is frequent in verbs when a penultimate tone causes the deletion of a final tone:

- ku-góná > ku-góna

A tone deleted by Meeussen's Rule can be replaced by spreading. Thus although ku-góna loses its final tone, the first tone can spread in a phrase such as ku-góná bwino 'to sleep well'.[34]

An instance where Meeussen's Rule does not apply in Chichewa is when the aspect-marker -ká- 'go and' is added to a verb, for example: a-ná-ká-thandiza 'he went and helped'. So far from being deleted, this tone can itself spread to the next syllable, e.g. a-ná-ká-thándiza.[35] The tone of an object-marker such as -mú- 'him' in the same position, however, is deleted by Meeussen's Rule and then replaced by spreading; it does not itself spread: a-ná-mú-thandiza 'he helped him'. In the Southern Region, the spreading does not occur, and the tones are a-ná-mu-thandiza.

Tone of consonants

[edit]Just as in English, where in a word like zoo or wood or now the initial voiced consonant has a low pitch compared with the following vowel, the same is true of Chichewa. Thus Trithart marks the tones of initial consonants such as [m], [n], [z], and [dz] in some words as Low.[36]

However, an initial nasal consonant is not always pronounced with a low pitch. After a high tone it can acquire a high tone itself, e.g. wá ḿsodzi 'of the fisherman'[37] The consonants n and m can also have a high tone when contracted from ndí 'and' or high-toned -mú-, e.g. ḿmakhálá kuti? (short for múmakhálá kuti?) 'where do you live?'.[38]

In some Southern African Bantu languages such as Zulu a voiced consonant at the beginning of a syllable not only has a low pitch itself, but can also lower the pitch of all or part of the following vowel. Such consonants are known as 'depressor consonants'. The question of whether Chichewa has depressor consonants was first considered by Trithart (1976) and further by Cibelli (2012). According to data collected by Cibelli, a voiced or nasalised consonant does indeed have a small effect on the tone of a following vowel, making it a semitone or more lower; so that for example the second vowel of ku-gúla 'to buy' would have a slightly lower pitch than that of ku-kúla 'to grow' or ku-khála 'to sit'. When the vowel is toneless, the effect is less, but it seems that there is still a slight difference. The effect of depressor consonants in Chichewa, however, is much less noticeable than in Zulu.

Chichewa Tenses

[edit]The past tenses in Chichewa differ from the perfect tenses in that they generally describe situations which were true in the past but of which the results no longer apply at the present time. Thus Maxson describes the Recent Past and the Remote Past as both implying that the situation has been "reversed or interrupted by another action".[39] According to Watkins, the Remote Past tense would be appropriate in a sentence such as "Jesus Christ died (but rose again)"; whereas it would not be appropriate in the sentence "God created the world" since it would imply that the creation was cancelled and "a second creator did a more enduring piece of work".[40] Similarly, according to Kulemeka, the Recent Past would be inappropriate in a sentence such as "our cat died", since it would imply that the act of dying was not permanent but would allow the possibility that the cat could come to life again at some future time.[41]

These two tenses, therefore, appear to differ from the English past tense (which is neutral in implication), and would seem to belong to the category of past tenses known in modern linguistics as discontinuous past.[42] Just as the Perfect and the Past Simple both carry the implication that the action had an enduring effect which continues to the present time, so the Recent Past and Remote Past carry the opposite implication, that the action was not permanent but was reversed or cancelled by a later action.

The Recent Past tense can also be used for narrating events that occurred earlier on the day of speaking.[43] (The use of the Perfect tense for narrative as described by Watkins[44] is now apparently obsolete). However, for narrating a series of events of yesterday or earlier, the Remote Perfect tense is used.[45]

Recent Past (-na-)

[edit]The Recent Past is made with the tense-marker -na-. The tone comes on the syllable immediately after -na-: ndinathándiza "I helped (but...)".

For the Recent Past tense, -na- is preferred.[46] -da- is regarded as incorrect by Malawian teachers for events of today,[47] but is sometimes heard colloquially.

The Recent Past is most often used for events of today, but it can also be used of earlier events. Although it can be used for simple narrative of events of earlier today, it usually carries the implication that the result of the action no longer holds true:

- Anapítá ku Zombá, koma wabweráko.

"He went to Zomba, but he has come back."[48] - Ndinaíká m'thumba.

"I (had) put it in my pocket (but it isn't there now)." - Anabwéra.

"He came just now (but has gone away again)."[49]

With the same verbs in which the Perfect tense describes a state in the present, the Recent Past describes a state in the recent past:

- Anaválá súti (= Analí átáválá súti).

"He was wearing a suit" (literally, "he had put on a suit"). - Anakhálá pafúpi.

"He was sitting nearby." - Kodí bambo, munanyámula munthu wína áliyensé m'gálímoto?

"Were you carrying anyone else in the car, sir?"

It can also be used, however, as a simple past tense for narrative of events of earlier today:[50]

- Ndimayéndá m'nkhalangó. Mwádzídzidzi ndinapóndá njóka.

"I was walking in the forest. Suddenly I stepped on a snake."

Although the tenses with -na- are usually perfective, the verb -li "be" is exceptional since the Recent Past and Remote Past in this tense usually have an imperfective meaning:

- Ndinalí wókóndwa kwámbíri.[51]

"I was very pleased."

A negative form of this tense (síndínafótókoza "I didn't explain", with a tone following na, and with the ending -a) is recorded by Mtenje.[52] However, the negative seems to be rarely if ever used in modern standard Chichewa, and it is not mentioned by most other writers. Instead, the negative of the Remote Perfect (síndínafotokóze, with tones on the first and penultimate, and with the ending -e) is generally used.

Remote Past (-dáa- / -náa-)

[edit]For the Remote Past tense, some dialects use -naa- and others -daa-. In some books, such as the 1998 Bible translation, Buku Loyera, this tense-marker is always spelled -daa-, but in other publications the spelling -na- or -da- is used, so that only the context makes it clear whether the Past Simple or the Remote Past is intended.[53]

There are tones on the 1st, 2nd, and penultimate syllables. The first tone[54] or the second tone can be omitted: ndi-ná-a-gúla; ndí-na-a-gúla "I (had) bought (but...)". This tense is a remote one, used of events of yesterday or earlier. The a of the tense-marker is always long, even though it is often written with a single vowel.

As might be expected of a tense which combines the past tense marker -na- or -da- and the Perfect tense marker -a-, this tense can have the meaning of a Pluperfect:

- Mkatí mwá chítupamo ádâdíndá chilolezo.[55]

"Inside the passport they had stamped a visa." - Khamú lálíkúlu lidámtsatira, chifukwá lídáaóná zizindikiro zózízwitsa.[56]

"A large crowd followed him, because they had seen amazing signs."

It can also be used to describe a situation in the distant past, using the same verbs which are used in the Perfect tense to describe a situation in the present:

- Kunjáko kúdâyíma máyi wónénepa. Mmanja ádanyamúla páketi yá mowa.

"A fat woman was standing outside; in her hand she was carrying a packet of beer." - Ndidápézá msúngwana wína átátámbalalá pamchenga. Ádâválá chitenje.

"I found certain girl sitting on the sand; she was wearing a chitenje."

The same meaning is often expressed with a compound verb: adáli átávála chitenje (see below for examples.)

Another common use of this tense is as a discontinuous past, expressing a situation in the past which later came to be cancelled or reversed:[57]

- Ndídáalandírá makúponi koma ndidágulitsa.

"I received some coupons but I sold them." - Anzáke ádáamulétsa, iyé sádamvére.

"Her friends tried to stop her but she wouldn't listen." - Nkhósa ídáatayíka.

"The sheep was lost (but has been found)."[58] - Ádáabádwa wósapénya.

"He was born blind (but has regained his sight)."[59]

Imperfect tense (-ma-)

[edit]The usual Past Imperfective tense, or simply the Imperfect tense, is made with the tense-marker -ma-. The tones are the same as for the Present Continuous and the Recent Past, that is, there is a tone on the syllable immediately after -ma. The negative also has a tone after -ma-: síndímathándiza "I wasn't helping".[60] This tense can refer either to very recent time or to remote time in the past:[61]

The imperfect sometimes has a progressive meaning:[62]

- Ndikhúlúlukiréni. Ndimalákwa.

"Forgive me. I was doing wrong." - Haaa! Kodí ndimalóta?

"Ha! Was I dreaming?" - Ntháwi iméneyo umachókera kuti?

"At that time where were you coming from?"

It can also be used for habitual events in the past:[62]

- M'kalási timakhálira limódzi.

"In class we used to sit together."

The negative also has a tone on the syllable following the infix -ma-, as well as one on si-:[63]

- Síndímadzíwa kutí mwafika.

"I didn't know that you had arrived."

Remote Imperfect (-nká-)

[edit]Remote Imperfect or Remote Past Imperfective is formed with the tense-marker -nka-. There are tones on nká and on the penultimate: ndinkáthandíza "I was helping/ used to help". It refers to events of yesterday or earlier.[61] Since the Past Imperfective with -ma- can be used of both near and remote events, whereas -nka- can be used only for remote ones, the -nka- tense is perhaps less commonly used.

This tense is used for both habitual events in the distant past, and progressive events in the distant past:

- Chaká chátha ankápítá kusukúlu, koma chaká chino amángokhála.[64]

"Last year he used to go to school, but this year he just stays at home." - Ndinkáyéndá m'nkhalangó.[65]

"I was walking in the forest."

The tense-marker -nká-, which is pronounced with two syllables, is possibly derived from the verb muká or mká 'go'.[66]

Catawba

[edit]People have lived in the area since the Paleoindian period (~10,000 B.C.). Pottery along the Catawba river corridor have been found that date to the Woodland period. The Catawba were the people who inhabited the area when Europeans first began to settle.[67]

In the late 19th century, the ethnographer Henry Rowe Schoolcraft theorized that the Catawba had lived in Canada until driven out by the Iroquois (supposedly with French help) and that they had migrated to Kentucky and to Botetourt County, Virginia. He asserted that by 1660 they had migrated south to the Catawba River, competing in this territory with the Cherokee, a Southern Iroquoian language–speaking tribe who were based west of the French Broad River in southwestern North Carolina, southeastern Tennessee, northwestern South Carolina, and northeastern Georgia.[68]

However, early 20th-century anthropologist James Mooney later dismissed most elements of Schoolcraft's account as "absurd, the invention and surmise of the would-be historian who records the tradition." He pointed out that, aside from the French never having been known to help the Iroquois, the Catawba had been recorded by 1567 by the Spanish expedition under Juan Pardo as being in the same area of the Catawba River as was known to be their later territory. Mooney accepted the tradition that, following a protracted struggle, the Catawba and Cherokee had settled on the Broad River their mutual boundary.[68]

The Catawba also had armed confrontations with several northern tribes, particularly the Haudenosaunee Seneca nation, and the Algonquian-speaking Lenape, with whom they competed for hunting resources and territory. The Catawba chased Lenape raiding parties back to the north in the 1720s and 1730s, going across the Potomac River. At one point, a party of Catawba is said to have followed a party of Lenape who attacked them, and to have overtaken them near Leesburg, Virginia. There they fought a pitched battle.[69]

Similar encounters in these longstanding conflicts were reported to have occurred at present-day Franklin, West Virginia (1725),[70] Hanging Rocks and the mouth of the Potomac South Branch in West Virginia, and near the mouths of Antietam Creek (1736) and Conococheague Creek in Maryland.[71] Mooney asserted that the name of Catawba Creek in Botetourt came from an encounter in these battles with the northern tribes, not from the Catawba having lived there.[68]

In 1721 the colonial governments of Virginia and New York held a council at Albany, New York, attended by delegates from the Six Nations (Haudenosaunee) and the Catawba. The colonists asked for peace between the Confederacy and the Catawba. The Six Nations reserved the land west of the Blue Ridge Mountains for themselves, including the Indian Road or Great Warriors' Path (later called the Great Wagon Road) through the Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia backcountry. This path was frequently traveled and was used until 1744 by Seneca war parties to pass through the Shenandoah Valley to raid in the South.[citation needed]

In 1738, a smallpox epidemic broke out in South Carolina. Endemic for centuries among Europeans, the infectious disease had been carried by them to North America, where it caused many deaths. The Catawba and other tribes, such as the Sissipahaw, suffered high mortality in these epidemics. In 1759, a smallpox epidemic killed nearly half the Catawba.[citation needed]

In 1744 the Treaty of Lancaster, made at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, renewed the Covenant Chain between the Iroquois and the colonists. The governments had not been able to prevent settlers going into Iroquois territory, but the governor of Virginia offered the tribe payment for their land claim. The peace was probably final for the Iroquois, who had established the Ohio Valley as their preferred hunting ground by right of conquest and pushed other tribes out of it.

Tribes located to the west continued warfare against the Catawba, who were so reduced that they could raise little resistance. In 1763, a small party of Algonquian Shawnee killed the noted Catawba chief, King Hagler, near his own village.[72]

In 1763, the colonial government of South Carolina confirmed a reservation for the Catawba of 225 square miles (580 km2; 144,000 acres), on both sides of the Catawba River, within the present York and Lancaster counties. When British troops approached during the American Revolutionary War in 1780, the Catawba withdrew temporarily into Virginia. They returned after the Battle of Guilford Court House, and settled in two villages on the reservation. These were known as Newton, the principal village, and Turkey Head, on the opposite side of the Catawba/Wateree River.[citation needed]

19th century

[edit]In 1826, the Catawba leased nearly half their reservation to whites for a few thousand dollars of annuity; their dwindling number of members (as few as 110 by an 1896 estimate)[73] depended on this money for survival.

In 1840, by the Treaty of Nation Ford with South Carolina, the Catawba sold to the state all but one square mile (2.6 km2) of their 144,000 acres (225 sq mi; 580 km2) reserved by the English Crown. They resided on the remaining square mile after the treaty. The treaty was invalid ab initio because the state did not have the right to make it, which was reserved for the federal government, and never gained Senate ratification. and did not get federal approval.[74] About the same time, a number of the Catawba, dissatisfied with their condition among the whites, removed to join the remaining eastern Cherokee, who were based in far Western North Carolina. But, finding their position among their former enemies equally unpleasant, all but one or two soon returned to South Carolina. The last survivor of the westward migration, an elderly Catawba woman, died among the Cherokee in 1889. A few Cherokee intermarried with the Catawba in the region.

At a later period some Catawba removed to the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory and settled near present-day Scullyville, Oklahoma. They assimilated with the Choctaw and did not retain separate tribal identity.

The Catawba fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. Nineteen men enlisted with the Confederate Army and saw combat across Virginia.[75]

Historical culture and estimated populations

[edit]The Catawba are historically sedentary agriculturists, who have also fished and hunted for game. Their customs have been, and are, similar to neighboring Native Americans in the Piedmont region. Traditional game has included deer, crops grown have included corn, and the women in particular are noted makers of pottery and baskets, arts which they still preserve. They are believed to have the oldest surviving tradition of pottery East of the Mississippi, and possibly the oldest (or one of the oldest) on the American continent.[76]

Early Spanish explorers of the mid-16th century estimated the population of the Catawba as between 15,000 and 25,000 people. When the English first settled South Carolina about 1682, they estimated the Catawba at about 1,500 warriors, or about 4,600 people in total. Their decline was attributed to the mortality of infectious diseases. The English named the Catawba River and Catawba County after this indigenous people. By 1728, the Catawba had been reduced to about 400 warriors, or about 1400 persons in total. In 1738, they suffered from a smallpox epidemic, which also affected nearby tribes and the whites. In 1743, even after incorporating several small tribes, the Catawba numbered fewer than 400 warriors. In 1759, they again suffered from smallpox, and in 1761, had some 300 warriors, or about 1,000 people. By 1775 they had only 400 people in total; in 1780, they had 490; and, in 1784, only 250 were reported.[citation needed]

During the nineteenth century, their numbers continued to decline, to 450 in 1822, and a total of 110 people in 1826. As of 2006, their population had increased to about 2600.[citation needed]

Religion and culture

[edit]

The customs and beliefs of the early Catawba were documented by the anthropologist Frank Speck in the twentieth century. In the Carolinas, the Catawba became well known for their pottery, which historically was made primarily by the women. Since the late 20th century, some men also make pottery.[77]

In approximately 1883, tribal members were contacted by missionaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Numerous Catawba were converted to the church. Some left the Southeast to resettle with clusters of Mormons in Utah, Colorado, and neighboring western states.[78]

The Catawba on their reserve in South Carolina hold a yearly celebration called Yap Ye Iswa, which roughly translates to "Day of the People," or Day of the River People. Held at the Catawba Cultural Center, proceeds are used to fund the activities of the center.

20th century to present

[edit]

The Catawba were electing their chief prior to the start of the 20th century. In 1909 the Catawba sent a petition to the United States government seeking to be given United States citizenship.[79]

During President Franklin D. Roosevelt's administration, the federal government worked to improve conditions for Native Americans. Under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, tribes were encouraged to renew their governments to exercise more self-determination. The Catawba were not at that time a recognized Native American tribe as they had lost their land and did not have a reservation. In 1929 Samuel Taylor Blue, chief of the Catawba, had begun the process to gain federal recognition.

The Catawba were federally recognized as a Native American tribe in 1941, and they created a written constitution in 1944. Also in 1944 South Carolina granted the Catawba and other Native American residents of the state citizenship, but did not grant them the franchise, or right to vote. Like African Americans since the turn of the 20th century, the Native Americans were largely excluded from the franchise by discriminatory rules and practices associated with voter registration. They were prevented from voting until the late 1960s, after the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed. It provided for federal oversight and enforcement of people's constitutional right to vote.

In the 1950s, the federal government began to press what is known as the Indian termination policy, based on its perception that some tribes were assimilated enough not to need a special relationship with the government. It terminated the government of the Catawba in 1959. This cut off federal benefits, and communal property was allocated to individual households. The people became subject to state law. The Catawba decided that they preferred to be organized as a tribal community. Beginning in 1973, they applied to have their government federally recognized. Gilbert Blue served as their chief until 2007. They adopted a constitution in 1975 that was modeled on their 1944 version.

In addition, for decades the Catawba pursued various land claims against the government for the losses due to the illegal treaty made by South Carolina in 1840 and the failure of the federal government to protect their interests. This culminated in South Carolina v. Catawba Indian Tribe, Inc., where the United States Supreme Court ruled that the tribe's land claims were subject to a statute of limitations which had not yet run out. In response, the Catawba prepared to file 60,000 lawsuits against individual landowners in York County to regain ownership of their land.[80] On October 27, 1993, the U.S. Congress enacted the Catawba Indian Tribe of South Carolina Land Claims Settlement Act of 1993 (Settlement Act), which reversed the "termination", recognized the Catawba Indian Nation and, together with the state of South Carolina, settled the land claims for $50 million, to be applied toward economic development for the Nation.[81]

On July 21, 2007, the Catawba held their first elections in more than 30 years. Of the five members of the former government, only two were reelected.[82]

In the 2010 census, 3,370 people identified as having Catawba ancestry.

Muckleshoot

[edit]Muckleshoot Indian Tribe bəqəlšuɬ | |

|---|---|

Location of the Muckleshoot Reservation | |

| Languages | Lushootseed, English |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Demonym(s) | Muckleshoot |

| Type | Federally-recognized tribe |

| Legislature | Muckleshoot Tribal Council |

| Establishment | |

| December 26, 1854 | |

| 1855 | |

• Muckleshoot Reservation established | January 20, 1857 |

• Constitution ratified | October 21, 1936 |

The Muckleshoot Indian Tribe (/ˈmʌkəlʃut/ MUH-kəl-shoot; Lushootseed: bəqəlšuɬ [ˈbəqəlʃuɬ]), also known as the Muckleshoot Tribe, is a federally-recognized tribe located in Auburn, Washington. The tribe governs the Muckleshoot Reservation and is composed of descendants of the Duwamish, Stkamish, Smulkamish, Skopamish, Yilalkoamish, and Upper Puyallup peoples. The Muckleshoot Indian Tribe was formally established in 1936, after the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, but its origins lie in the creation of the Muckleshoot Reservation in 1874 and the treaties of Medicine Creek (1854) and Point Elliott (1855). The Muckleshoot Indian Tribe is the successor of various groups which lived along the Duwamish River's watershed, and parts of the upper Puyallup River's watershed. These include the:

- Duwamish[83][84]

- Stkamish[83][84]

- Smulkamish[83][84]

- Skopamish,[84] the name for all peoples living along the Green River. This term covered eight to ten independent villages along the river, such as the Yilalkoamish.[83][85]

- Upper Puyallup peoples[84]

The Muckleshoot reservation

[edit]The origins of the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe lie in the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek and the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott.[83][86] Although the Stkamish, Skopamish, and Smulkamish bands are mentioned in the preamble to the Treaty of Point Elliott, they did not sign the treaty directly. Along with the Sammamish, they were assumed by the territorial governor of Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens, to be under the control of the Duwamish and Seattle. It was Stevens' desire to alter the traditional political organization of the Indigenous peoples in the area by appointing single "chiefs" as leaders of entire groups, noting the "difficulties in trying to control an indigenous population without strong chiefs and centralized authority." The decision of creating these political officices was not based on the indigenous social organization, and as such, Seattle was appointed as a "head chief" of a Duwamish Tribe that included all the peoples living along the Duwamish watershed, including the Green and White rivers' population.[87] For this reason, the Muckleshoot Tribe has variously claimed that they have both a treaty and non-treaty status. Furthermore, the Muckleshoot Reservation exists on territory ceded by the Treaty of Point Elliott, but was dictated by the Treaty of Medicine Creek (and only the Medicine Creek treaty was ratified at the time), further contributing to the confusion.[88]

The treaties were unpopular with many, and due to the continuing hostility, the Puget Sound War began shortly after, in 1855. The ancestral bands of the Muckleshoot joined the war against the American government.[89] At the war's conclusion, during the Fox Island Council, governor Stevens agreed to the establishment of a new reservation for groups who had not received a reservation under the prior treaties. At Fox Island, Stevens agreed that a reservation would be created in all the lands between the White and Green rivers, including Muckleshoot Prairie.[83]

The Muckleshoot Reservation was eventually established on January 20, 1857 by an executive order from U.S. president Franklin Pierce. However, the reservation did not include all the land previously promised at the Fox Island Council, including traditional fishing and village sites. The reservation would be later expanded in 1874 by president Ulysses S. Grant.[83]

Establishment of the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe

[edit]In 1934, the Indian Reorganization Act allowed Native Americans living on reservations to establish their own governments. The peoples of the Muckleshoot Reservation voted to establish the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe. In 1936, they established a constitution and bylaws. Around this time, in 1937, the Muckleshoot Tribe had 194 enrolled members.[83][89]

Fights for treaty rights

[edit]The Muckleshoot Tribe were denied their land claims in Duwamish Indians v. United States, on the basis that there was no treaty with the "Muckleshoot". Later, however, in 1959, the Indian Claims Commission found that the ancestors of the Muckleshoot had possessed 101,620 acres (158.78 sq mi; 411.2 km2) of land, valued at $86,377. On March 8, 1959, the Commission ordered that the Muckleshoot Tribe be paid that amount by the United States.[90]

A large Army quartermaster depot was established in the Green River Valley at the south end of Auburn to take advantage of railways. It served the ports along Puget Sound, supporting the US war effort in the Pacific. In the post-World War II era, Auburn began to be more industrialized. Together with rapid population growth in the region, which developed many suburbs, these changes put pressure on the Muckleshoot and their reservation holdings. Many private land owners tried to prevent them from fishing and hunting in traditional territories.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Muckleshoot engaged in a series of protests,[91] intended at protecting their fragile ecosystem. Known as the Fish Wars, these protests attempted to preserve Muckleshoot fishing rights in nearby rivers that were not within the official reservation. County and state authorities had tried to regulate their fishing off-reservation. Similarly, the state tried to regulate other tribes in their fishing along the coastal waters.

In the Boldt Decision, the federal district court upheld the right of the Muckleshoot and other Treaty peoples to fish from the rivers of the region and hunt in these territories. It ruled that the Native Americans had rights to half the catch in their traditional areas. It designated the Muckleshoot as co-managers of the King County watershed, with control over fishing and hunting in their "Usual and Accustomed" historical fishing and hunting grounds.

While this improved the tribe's economic standing, the Muckleshoot were soon forced to contend with a sharp decline in the salmon population, due to the adverse effects on the environment, especially river water quality, of urbanization and industrialization. Dams on rivers had decreased the fish populations that could get upstream to spawn, and water quality in the rivers had declined. While they continue to fight for the preservation of the ancient salmon runs, the Muckleshoot also found other venues to improve their economy.

The Muckleshoot speak the southern dialect of Lushootseed, called Whulshootseed. The specific variety of Southern Lushootseed spoken at Muckleshoot is called bəqəlšuɬucid, 'Muckleshoot language'.[92] Use of the language has declined, and English is now the majority language. However, the tribe has been engaging in revitalizing the language. Muckleshoot citizens Earnie Barr, Eva Jerry, Bertha McJoe, Bernice Tanewasha, and Ellen Williams were involved in creating a written form for Lushootseed.[84]

The Muckleshoot Tribe holds Skopabsh Days each August, which is a three-day festival that features traditional arts, crafts, cooking, and clothing. Additionally, each July, the Muckleshoot Tribe hosts the Muckleshoot Sobriety Powwow.[93]

In the First Salmon Ceremony, the entire community shares the flesh of a Spring Chinook. They return its remains to the river where it was caught. This is so the salmon can inform the other fish of how well it was received. The other ceremony for the first salmon is to roast it until it becomes ashes. The Muckleshoot toss the bones and ashes back into the water or stream where they took the salmon, believing that the fish would come alive again (be part of a round of new propagation).[citation needed]

French consonants

[edit]| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Palatal/ Postalv. |

Velar/ Uvular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | |

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | |

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | |

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ʁ | |

| Approximant | plain | l | j | ||

| labial | ɥ | w | |||

Phonetic notes:

- /n, t, d/ are laminal denti-alveolar [n̪, t̪, d̪],[95][96] while /s, z/ are dentalised laminal alveolar [s̪, z̪] (commonly called 'dental'), pronounced with the blade of the tongue very close to the back of the upper front teeth, with the tip resting behind lower front teeth.[95][97]

- Word-final consonants are always released. Generally, /b, d, ɡ/ are voiced throughout and /p, t, k/ are unaspirated.[98]

- /l/ is usually apical alveolar [l̺] but sometimes laminal denti-alveolar [l̪].[96] Before /f, ʒ/, it can be realised as retroflex [ɭ].[96]

- In current pronunciation, /ɲ/ is merging with /nj/.[99]

- The velar nasal /ŋ/ is not a native phoneme of French, but it occurs in loan words such as camping, smoking or kung-fu.[100] Some speakers who have difficulty with this consonant realise it as a sequence [ŋɡ] or replace it with /ɲ/.[101] It could be considered a separate phoneme in Meridional French, e.g. pain /pɛŋ/ ('bread') vs. penne /pɛn/ ('quill').

- The approximants /j, ɥ, w/ correspond to the close vowels /i, y, u/. While there are a few minimal pairs (such as loua /lu.a/ 's/he rented' and loi /lwa/ 'law'), there are many cases where there is free variation.[98]

- Belgian French may merge /ɥ/ with /w/ or /y/.[citation needed]

- Some dialects of French have a palatal lateral /ʎ/ (French: l mouillé, 'wet l'), but in the modern standard variety, it has merged with /j/.[102][103] See also Glides and diphthongs, below.

- The French rhotic has a wide range of realizations: the voiced uvular fricative [ʁ], also realised as an approximant [ʁ̞], with a voiceless positional allophone [χ], the uvular trill [ʀ], the alveolar trill [r], and the alveolar tap [ɾ]. These are all recognised as the phoneme /r/,[98] but [r] and [ɾ] are considered dialectal. The most common pronunciation is [ʁ] as a default realisation, complemented by a devoiced variant [χ] in the positions before or after a voiceless obstruent or at the end of a sentence. See French guttural r and map at right.

- Velars /k/ and /ɡ/ may become palatalised to [kʲ⁓c] and [ɡʲ⁓ɟ] before /i, e, ɛ/, and more variably before /a/.[104] Word-final /k/ may also be palatalised to [kʲ].[105] Velar palatalisation has traditionally been associated with the working class,[106] though recent studies suggest it is spreading to more demographics of large French cities.[105]

| Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | Example | Gloss | IPA | Example | Gloss | ||

| /p/ | /pu/ | pou | 'louse' | /b/ | /bu/ | boue | 'mud' |

| /t/ | /tu/ | tout | 'all', 'anything' (possibility) | /d/ | /du/ | doux | 'sweet' (food, feelings), 'gentle' (person), 'mild' (weather) |

| /k/ | /ku/ | cou | 'neck' | /ɡ/ | /ɡu/ | goût | 'taste' |

| /f/ | /fu/ | fou | 'crazy' | /v/ | /vu/ | vous | 'you' |

| /s/ | /su/ | sous | 'under', 'on' (drugs), 'in' (packaging), 'within' (times) | /z/ | /zu/ | zou | 'shoo' |

| /ʃ/ | /ʃu/ | chou | 'cabbage', 'lovely' (person, pet) | /ʒ/ | /ʒu/ | joue | 'cheek' |

| /m/ | /mu/ | mou | 'soft', 'weak' (stronger: person, actions) | ||||

| /n/ | /nu/ | nous | 'we, us' | ||||

| /ɲ/ | /ɲu/ | gnou | 'gnu' (dated, /ɡnu/ in modern French) | ||||

| /ŋ/ | /kuŋ.fu/ | kung-fu | 'kung-fu' | ||||

| /l/ | /lu/ | loup | 'wolf' | ||||

| /ʁ/ | /ʁu/ | roue | 'wheel' | ||||

Geminates

[edit]Although double consonant letters appear in the orthographic form of many French words, geminate consonants are relatively rare in the pronunciation of such words. The following cases can be identified.[108]

The geminate pronunciation [ʁʁ] is found in the future and conditional forms of the verbs courir ('to run') and mourir ('to die'). The conditional form il mourrait [il.muʁ.ʁɛ] ('he would die'), for example, contrasts with the imperfect form il mourait [il.mu.ʁɛ] ('he was dying'). Most modern speakers have reduced [ʁʁ] to [ʁ] in other words, such as il pourrait ('he could'). Other verbs that have a double ⟨rr⟩ orthographically in the future and conditional are pronounced with a simple [ʁ]: il pourra ('he will be able to'), il verra ('he will see').

When the prefix in- combines with a base that begins with n, the resulting word is sometimes pronounced with a geminate [nn] and similarly for the variants of the same prefix im-, il-, ir-:

- inné [i(n).ne] ('innate')

- immortel [i(m).mɔʁtɛl] ('immortal')

- illisible [i(l).li.zibl] ('illegible')

- irresponsable [i(ʁ).ʁɛs.pɔ̃.sabl] ('irresponsible')

Other cases of optional gemination can be found in words like syllabe ('syllable'), grammaire ('grammar'), and illusion ('illusion'). The pronunciation of such words, in many cases, a spelling pronunciation varies by speaker and gives rise to widely varying stylistic effects.[109] In particular, the gemination of consonants other than the liquids and nasals /m n l ʁ/ is "generally considered affected or pedantic".[110] Examples of stylistically marked pronunciations include addition [ad.di.sjɔ̃] ('addition') and intelligence [ɛ̃.tɛl.li.ʒɑ̃s] ('intelligence').

Gemination of doubled ⟨m⟩ and ⟨n⟩ is typical of the Languedoc region, as opposed to other southern accents.

A few cases of gemination do not correspond to double consonant letters in the orthography.[111] The deletion of word-internal schwas (see below), for example, can give rise to sequences of identical consonants: là-dedans [lad.dɑ̃] ('inside'), l'honnêteté [lɔ.nɛt.te] ('honesty'). The elided form of the object pronoun l' ('him/her/it') is also realised as a geminate [ll] when it appears after another l to avoid misunderstanding:

- Il l'a mangé [il.lamɑ̃.ʒe] ('He ate it')

- Il a mangé [il.amɑ̃.ʒe] ('He ate')

Gemination is obligatory in such contexts.

Finally, a word pronounced with emphatic stress can exhibit gemination of its first syllable-initial consonant:

- formidable [fːɔʁ.mi.dabl] ('terrific')

- épouvantable [e.pːu.vɑ̃.tabl] ('horrible')

Liaison

[edit]Many words in French can be analyzed as having a "latent" final consonant that is pronounced only in certain syntactic contexts when the next word begins with a vowel. For example, the word deux /dø/ ('two') is pronounced [dø] in isolation or before a consonant-initial word (deux jours /dø ʒuʁ/ → [dø.ʒuʁ] 'two days'), but in deux ans /døz‿ɑ̃/ (→ [dø.zɑ̃] 'two years'), the linking or liaison consonant /z/ is pronounced.

French vowels

[edit]

Standard French contrasts up to 13 oral vowels and up to 4 nasal vowels. The schwa (in the center of the diagram next to this paragraph) is not necessarily a distinctive sound. Even though it often merges with one of the mid front rounded vowels, its patterning suggests that it is a separate phoneme (see the subsection Schwa below).

The table below primarily lists vowels in contemporary Parisian French, with vowels only present in other dialects in parentheses.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

While some dialects feature a long /ɛː/ distinct from /ɛ/ and a distinction between an open front /a/ and an open back /ɑ/, Parisian French features only /ɛ/ and just one open vowel /a/ realised as central [ä]. Some dialects also feature a rounded /œ̃/, which has merged with /ɛ̃/ in Paris.

In Metropolitan French, while /ə/ is phonologically distinct, its phonetic quality tends to coincide with either /ø/ or /œ/.

| Vowel | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | Orthography | Gloss | |

| Oral vowels | |||

| /i/ | /si/ | si | 'if' |

| /e/ | /fe/ | fée | 'fairy' |

| /ɛ/ | /fɛ/ | fait | 'does' |

| /ɛː/† | /fɛːt/ | fête | 'party' |

| /y/ | /sy/ | su | 'known' |

| /ø/ | /sø/ | ceux | 'those' |

| /œ/ | /sœʁ/ | sœur | 'sister' |

| /ə/ | /sə/ | ce | 'this'/'that' |

| /u/ | /su/ | sous | 'under' |

| /o/ | /so/ | sot | 'silly' |

| /ɔ/ | /sɔʁ/ | sort | 'fate' |

| /a/ | /sa/ | sa | 'his'/'her' |

| /ɑ/† | /pɑt/ | pâte | 'dough' |

| Nasal vowels | |||

| /ɑ̃/ | /sɑ̃/ | sans | 'without' |

| /ɔ̃/ | /sɔ̃/ | son | 'his' |

| /ɛ̃/[112] | /bʁɛ̃/ | brin | 'twig' |

| /œ̃/† | /bʁœ̃/ | brun | 'brown' |

| Semi-vowels | |||

| /j/ | /jɛʁ/ | hier | 'yesterday' |

| /ɥ/ | /ɥit/ | huit | 'eight' |

| /w/ | /wi/ | oui | 'yes' |

| † Not distinguished in all dialects. | |||

Close vowels

[edit]In contrast with the mid vowels, there is no tense–lax contrast in close vowels. However, non-phonemic lax (near-close) [ɪ, ʏ, ʊ] appear in Quebec as allophones of /i, y, u/ when the vowel is both phonetically short (so not before /v, z, ʒ, ʁ/) and in a closed syllable, so that e.g. petite [pə.t͡sɪt] 'small (f.)' differs from petit 'small (m.)' [pə.t͡si] not only in the presence of the final /t/ but also in the tenseness of the /i/. Laxing always occurs in stressed closed syllables, but it is also found in other environments to various degrees.[113][114]

In Metropolitan French, /i, u/ are consistently close [i, u],[115][116][117] but the exact height of /y/ is somewhat debatable as it has been variously described as close [y][115][116] and near-close [ʏ].[117]

Mid vowels

[edit]Although the mid vowels contrast in certain environments, there is a limited distributional overlap so they often appear in complementary distribution. Generally, close-mid vowels (/e, ø, o/) are found in open syllables, and open-mid vowels (/ɛ, œ, ɔ/) are found in closed syllables. However, there are minimal pairs:[115]

- open-mid /ɛ/ and close-mid /e/ contrast in final-position open syllables:

- likewise, open-mid /ɔ/ and /œ/ contrast with close-mid /o/ and /ø/ mostly in closed monosyllables, such as these:

Beyond the general rule, known as the loi de position among French phonologists,[118] there are some exceptions. For instance, /o/ and /ø/ are found in closed syllables ending in [z], and only [ɔ] is found in closed monosyllables before [ʁ], [ɲ], and [ɡ].[119]

The Parisian realization of /ɔ/ has been variously described as central [ɞ][117] and centralized to [ɞ] before /ʁ/,[95] in both cases becoming similar to /œ/.

The phonemic opposition of /ɛ/ and /e/ has been lost in the southern half of France, where these two sounds are found only in complementary distribution. The phonemic oppositions of /ɔ/ and /o/ and of /œ/ and /ø/ in terminal open syllables have been lost in almost all of France, but not in Belgium or in areas with an Arpitan substrate, where pot and peau are still opposed as /pɔ/ and /po/.[120]

Open vowels

[edit]The phonemic contrast between front /a/ and back /ɑ/ is sometimes no longer maintained in Parisian French, which leads some researchers to reject the idea of two distinct phonemes.[121] However, the back [ɑ] is always maintained in Northern French, but only in final open syllables,[122] avocat (lawyer) [avokɑ] ⓘ, but in final closed syllables, the /ɑ/ phoneme is fronted to [aː], but it is always long, pâte (pasta) [paːt]. The distinction is still clearly maintained in many dialects such as Quebec French.[123]

While there is much variation among speakers in France, a number of general tendencies can be observed. First of all, the distinction is most often preserved in word-final stressed syllables such as in these minimal pairs:

- tache /taʃ/ → [taʃ] ('stain'), vs. tâche /tɑʃ/ → [tɑʃ] ('task')

- patte /pat/ → [pat] ('leg'), vs. pâte /pɑt/ → [pɑt] ('paste, pastry')

- rat /ʁa/ → [ʁa] ('rat'), vs. ras /ʁɑ/ → [ʁɑ] ('short')

There are certain environments that prefer one open vowel over the other. For example, /ɑ/ is preferred after /ʁw/ and before /z/:

The difference in quality is often reinforced by a difference in length (but the difference is contrastive in final closed syllables). The exact distribution of the two vowels varies greatly from speaker to speaker.[125]

Back /ɑ/ is much rarer in unstressed syllables, but it can be encountered in some common words:

Morphologically complex words derived from words containing stressed /ɑ/ do not retain it:

- âgé /ɑʒe/ → [aː.ʒe] ('aged', from âge /ɑʒ/ → [ɑʒ])

- rarissime /ʁaʁisim/ → [ʁaʁisim] ('very rare', from rare /ʁɑʁ/ → [ʁɑʁ]).

Even in the final syllable of a word, back /ɑ/ may become [a] if the word in question loses its stress within the extended phonological context:[124]

- J'ai été au bois /ʒe ete o bwɑ/ → [ʒe.e.te.o.bwɑ] ('I went to the woods'),

- J'ai été au bois de Vincennes /ʒe ete o bwɑ dəvɛ̃sɛn/ → [ʒe.e.te.o.bwad.vɛ̃.sɛn] ('I went to the Vincennes woods').

Nasal vowels

[edit]The phonetic qualities of the back nasal vowels differ from those of the corresponding oral vowels. The contrasting factor that distinguishes /ɑ̃/ and /ɔ̃/ is the extra lip rounding of the latter according to some linguists,[126] and tongue height according to others.[127] Speakers who produce both /œ̃/ and /ɛ̃/ distinguish them mainly through increased lip rounding of the former, but many speakers use only the latter phoneme, especially most speakers in northern France such as Paris (but not farther north, in Belgium).[126][127]

In some dialects, particularly that of Europe, there is an attested tendency for nasal vowels to shift in a counterclockwise direction: /ɛ̃/ tends to be more open and shifts toward the vowel space of /ɑ̃/ (realised also as [æ̃]), /ɑ̃/ rises and rounds to [ɔ̃] (realised also as [ɒ̃]) and /ɔ̃/ shifts to [õ] or [ũ]. Also, in some regions, there also is an opposite movement for /ɔ̃/ for which it becomes more open like [ɒ̃], resulting in a merger of Standard French /ɔ̃/ and /ɑ̃/ in this case.[127][128] According to one source, the typical phonetic realization of the nasal vowels in Paris is [æ̃] for /ɛ̃/, [ɑ̃] for /ɑ̃/ and [õ̞] for /ɔ̃/, suggesting that the first two are unrounded open vowels that contrast by backness (like the oral /a/ and /ɑ/ in some accents), whereas /ɔ̃/ is much closer than /ɛ̃/.[129]

In Quebec French, two of the vowels shift in a different direction: /ɔ̃/ → [õ], more or less as in Europe, but /ɛ̃/ → [ẽ] and /ɑ̃/ → [ã].[130]

In the Provence and Occitanie regions, nasal vowels are often realized as oral vowels before a stop consonant, thus reviving the ⟨n⟩ otherwise lost in other accents: quarante /kaʁɑ̃t/ → [kaˈʁantə].

Contrary to the oral /ɔ/, there is no attested tendency for the nasal /ɔ̃/ to become central in any accent.

Schwa

[edit]When phonetically realised, schwa (/ə/), also called e caduc ('dropped e') and e muet ('mute e'), is a mid-central vowel with some rounding.[115] Many authors consider its value to be [œ],[131][132] while Geoff Lindsey suggests [ɵ].[133][134] Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006) state, more specifically, that it merges with /ø/ before high vowels and glides:

in phrase-final stressed position:

- dis-le ! /di lə/ → [di.ˈlø] ('say it'),

and that it merges with /œ/ elsewhere.[135] However, some speakers make a clear distinction, and it exhibits special phonological behavior that warrants considering it a distinct phoneme. Furthermore, the merger occurs mainly in the French of France; in Quebec, /ø/ and /ə/ are still distinguished.[136]

The main characteristic of French schwa is its "instability": the fact that under certain conditions it has no phonetic realization.

- That is usually the case when it follows a single consonant in a medial syllable:

- appeler /apəle/ → [ap.le] ('to call'),

- It is occasionally mute in word-final position:

- porte /pɔʁtə/ → [pɔʁt] ('door').

- Word-final schwas are optionally pronounced if preceded by two or more consonants and followed by a consonant-initial word:

- une porte fermée /yn(ə) pɔʁt(ə) fɛʁme/ → [yn.pɔʁ.t(ə).fɛʁ.me] ('a closed door').

- In the future and conditional forms of -er verbs, however, the schwa is sometimes deleted even after two consonants:[citation needed]

- tu garderais /ty ɡaʁdəʁɛ/ → [ty.ɡaʁ.d(ə.)ʁɛ] ('you would guard'),

- nous brusquerons [les choses] /nu bʁyskəʁɔ̃/ → [nu.bʁys.k(ə.)ʁɔ̃] ('we will precipitate [things]').

- On the other hand, it is pronounced word-internally when it follows more pronounced[clarification needed] consonants that cannot be combined into a complex onset with the initial consonants of the next syllable:

In French versification, word-final schwa is always elided before another vowel and at the ends of verses. It is pronounced before a following consonant-initial word.[138] For example, une grande femme fut ici, [yn ɡʁɑ̃d fam fy.t‿i.si] in ordinary speech, would in verse be pronounced [y.nə ɡʁɑ̃.də fa.mə fy.t‿i.si], with the /ə/ enunciated at the end of each word.

Schwa cannot normally be realised as a front vowel ([œ]) in closed syllables. In such contexts in inflectional and derivational morphology, schwa usually alternates with the front vowel /ɛ/:

- harceler /aʁsəle/ → [aʁ.sœ.le] ('to harass'), with

- il harcèle /il aʁsɛl/ → [i.laʁ.sɛl] ('[he] harasses').[139]

A three-way alternation can be observed, in a few cases, for a number of speakers:

- appeler /apəle/ → [ap.le] ('to call'),

- j'appelle /ʒ‿apɛl/ → [ʒa.pɛl] ('I call'),

- appellation /apelasjɔ̃/ → [a.pe.la.sjɔ̃] ('brand'), which can also be pronounced [a.pɛ.la.sjɔ̃].[140]

Instances of orthographic ⟨e⟩ that do not exhibit the behaviour described above may be better analysed as corresponding to the stable, full vowel /œ/. The enclitic pronoun le, for example, always keeps its vowel in contexts like donnez-le-moi /dɔne lə mwa/ → [dɔ.ne.lœ.mwa] ('give it to me') for which schwa deletion would normally apply (giving *[dɔ.nɛl.mwa]), and it counts as a full syllable for the determination of stress.

Cases of word-internal stable ⟨e⟩ are more subject to variation among speakers, but, for example, un rebelle /œ̃ ʁəbɛl/ ('a rebel') must be pronounced with a full vowel in contrast to un rebond /œ̃ ʁəbɔ̃/ → or [œ̃ʁ.bɔ̃] ('a bounce').[141]

Length

[edit]Except for the distinction still made by some speakers between /ɛ/ and /ɛː/ in rare minimal pairs like mettre [mɛtʁ] ('to put') vs. maître [mɛːtʁ] ('teacher'), variation in vowel length is entirely allophonic. Vowels can be lengthened in closed, stressed syllables, under the following two conditions:

- /o/, /ø/, /ɑ/, and the nasal vowels are lengthened before any consonant: pâte [pɑːt] ('dough'), chante [ʃɑ̃ːt] ('sings').

- All vowels are lengthened if followed by one of the voiced fricatives—/v/, /z/, /ʒ/, /ʁ/ (not in combination)—or by the cluster /vʁ/: mer/mère [mɛːʁ] ('sea/mother'), crise [kʁiːz] ('crisis'), livre [liːvʁ] ('book').[142][143] However, words such as (ils) servent [sɛʁv] ('(they) serve') or tarte [taʁt] ('pie') are pronounced with short vowels since the /ʁ/ appears in clusters other than /vʁ/.

When such syllables lose their stress, the lengthening effect may be absent. The vowel [o] of saute is long in Regarde comme elle saute !, in which the word is phrase-final and therefore stressed, but not in Qu'est-ce qu'elle saute bien ![144] In accents wherein /ɛː/ is distinguished from /ɛ/, however, it is still pronounced with a long vowel even in an unstressed position, as in fête in C'est une fête importante.[144]

The following table presents the pronunciation of a representative sample of words in phrase-final (stressed) position:

| Phoneme | Vowel value in closed syllable | Vowel value in open syllable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-lengthening consonant | Lengthening consonant | |||||

| /i/ | habite | [a.bit] | livre | [liːvʁ] | habit | [a.bi] |

| /e/ | — | été | [e.te] | |||

| /ɛ/ | faites | [fɛt] | faire | [fɛːʁ] | fait | [fɛ] |

| /ɛː/ | fête | [fɛːt] | rêve | [ʁɛːv] | — | |

| /ø/ | jeûne | [ʒøːn] | joyeuse | [ʒwa.jøːz] | joyeux | [ʒwa.jø] |

| /œ/ | jeune | [ʒœn] | œuvre | [œːvʁ] | — | |

| /o/ | saute | [soːt] | rose | [ʁoːz] | saut | [so] |

| /ɔ/ | sotte | [sɔt] | mort | [mɔːʁ] | — | |

| /ə/ | — | le | [lə] | |||

| /y/ | débute | [de.byt] | juge | [ʒyːʒ] | début | [de.by] |

| /u/ | bourse | [buʁs] | bouse | [buːz] | bout | [bu] |

| /a/ | rate | [ʁat] | rage | [ʁaːʒ] | rat | [ʁa] |

| /ɑ/ | appâte | [a.pɑːt] | rase | [ʁɑːz] | appât | [a.pɑ] |

| /ɑ̃/ | pende | [pɑ̃ːd] | genre | [ʒɑ̃ːʁ] | pends | [pɑ̃] |

| /ɔ̃/ | réponse | [ʁe.pɔ̃ːs] | éponge | [e.pɔ̃ːʒ] | réponds | [ʁe.pɔ̃] |

| /œ̃/ | emprunte | [ɑ̃.pʁœ̃ːt] | grunge | [ɡʁœ̃ːʒ] | emprunt | [ɑ̃.pʁœ̃] |

| /ɛ̃/ | teinte | [tɛ̃ːt] | quinze | [kɛ̃ːz] | teint | [tɛ̃] |

Devoicing

[edit]In Parisian French, the close vowels /i, y, u/ and the mid front /e, ɛ/ at the end of utterances can be devoiced. A devoiced vowel may be followed by a sound similar to the voiceless palatal fricative [ç]:

- Merci. /mɛʁsi/ → [mɛʁ.si̥ç] ('Thank you.'),

- Allez ! /ale/ → [a.le̥ç] ('Go!').[145]

In Quebec French, close vowels are often devoiced when unstressed and surrounded by voiceless consonants:

- université /ynivɛʁsite/ → [y.ni.vɛʁ.si̥.te] ('university').[146]

Though a more prominent feature of Quebec French, phrase-medial devoicing is also found in European French.[147]

Elision

[edit]The final vowel (usually /ə/) of a number of monosyllabic function words is elided in syntactic combinations with a following word that begins with a vowel. For example, compare the pronunciation of the unstressed subject pronoun, in je dors /ʒə dɔʁ/ [ʒə.dɔʁ] ('I am sleeping'), and in j'arrive /ʒ‿aʁiv/ [ʒa.ʁiv] ('I am arriving').

Glides and diphthongs

[edit]The glides [j], [w], and [ɥ] appear in syllable onsets immediately followed by a full vowel. In many cases, they alternate systematically with their vowel counterparts [i], [u], and [y] such as in the following pairs of verb forms:

The glides in the examples can be analyzed as the result of a glide formation process that turns an underlying high vowel into a glide when followed by another vowel: /nie/ → [nje].

This process is usually blocked after a complex onset of the form obstruent + liquid (a stop or a fricative followed by /l/ or /ʁ/). For example, while the pair loue/louer shows an alternation between [u] and [w], the same suffix added to cloue [klu], a word with a complex onset, does not trigger the glide formation: clouer [klu.e] ('to nail'). Some sequences of glide + vowel can be found after obstruent-liquid onsets, however. The main examples are [ɥi], as in pluie [plɥi] ('rain'), [wa], as in proie [pʁwa] ('prey'), and [wɛ̃], as in groin [ɡʁwɛ̃] ('snout').[148] They can be dealt with in different ways, as by adding appropriate contextual conditions to the glide formation rule or by assuming that the phonemic inventory of French includes underlying glides or rising diphthongs like /ɥi/ and /wa/.[149][150]

Glide formation normally does not occur across morpheme boundaries in compounds like semi-aride ('semi-arid').[151] However, in colloquial registers, si elle [si.ɛl] ('if she') can be pronounced just like ciel [sjɛl] ('sky'), or tu as [ty.ɑ] ('you have') like tua [tɥa] ('[(s)he] killed').[152]

The glide [j] can also occur in syllable coda position, after a vowel, as in soleil [sɔlɛj] ('sun'). There again, one can formulate a derivation from an underlying full vowel /i/, but the analysis is not always adequate because of the existence of possible minimal pairs like pays [pɛ.i] ('country') / paye [pɛj] ('paycheck') and abbaye [a.bɛ.i] ('abbey') / abeille [a.bɛj] ('bee').[153] Schane (1968) proposes an abstract analysis deriving postvocalic [j] from an underlying lateral by palatalization and glide conversion (/lj/ → /ʎ/ → /j/).[154]

| Vowel | Onset glide | Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /j/ | /ɥ/ | /w/ | ||

| /a/ | /ja/ | /ɥa/ | /wa/ | paillasse, Éluard, poire |

| /ɑ/ | /jɑ/ | /ɥɑ/ | /wɑ/ | acariâtre, tuas, jouas |

| /ɑ̃/ | /jɑ̃/ | /ɥɑ̃/ | /wɑ̃/ | vaillant, exténuant, Assouan |

| /e/ | /je/ | /ɥe/ | /we/ | janvier, muer, jouer |

| /ɛ/ | /jɛ/ | /ɥɛ/ | /wɛ/ | lierre, duel, mouette |

| /ɛ̃/ | /jɛ̃/ | /ɥɛ̃/ | /wɛ̃/ | bien, juin, soin |

| /i/ | /ji/ | /ɥi/ | /wi/ | yin, huile, ouïr |

| /o/ | /jo/ | /ɥo/ | /wo/ | Millau, duo, statuquo |

| /ɔ/ | /jɔ/ | /ɥɔ/ | /wɔ/ | Niort, quatuor, wok |

| /ɔ̃/ | /jɔ̃/ | /ɥɔ̃/ | /wɔ̃/ | lion, tuons, jouons |

| /ø/ | /jø/ | /ɥø/ | /wø/ | mieux, fructueux, boueux |

| /œ/ | /jœ/ | /ɥœ/ | /wœ/ | antérieur, sueur, loueur |

| /œ̃/ | — | — | — | |

| /u/ | /ju/ | — | /wu/ | caillou, Wuhan |

| /y/ | /jy/ | — | — | feuillu |

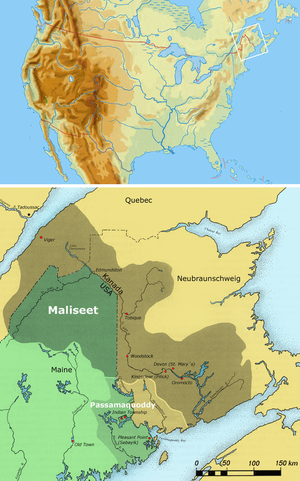

Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet)

[edit]

17th century

[edit]At the time of European encounter, the Wəlastəkwewiyik were living in walled villages and practicing horticulture (corn, beans, squash and tobacco). In addition to cultivating and growing crops, the women gathered and processed fruits, berries, nuts and natural produce. The men contributed by fishing and hunting, and the women cooked these finds. Written accounts in the early 17th century, such as those of Samuel de Champlain and Marc LesCarbot, refer to a large Wolastoqey village at the mouth of the Saint John River. Later in the century, sources indicate their headquarters had shifted upriver to Meductic, on the middle reaches of the Saint John River.

The French explorers were the first to establish a fur trade with the Wəlastəkwewiyik, which became important in their territory. Some European goods were desired because they were useful to Wəlastəkwewiyik subsistence and culture. The French Jesuits also established missions, where some Wəlastəkwewiyik converted to Catholicism. After years of colonialism, many learned the French language. The French called them Malécite, a transliteration of the Mi'kmaq name for the people.

Local histories depict many encounters with the Iroquois, five powerful nations based south and east of the Great Lakes, and the Innu located to the north. Contact with European fisher-traders in the early 17th century and with specialized fur traders developed into a stable relationship which lasted for nearly 100 years. Despite devastating population losses to European infectious diseases, to which they had no immunity, these Atlantic First Nations held on to their traditional coastal or river locations for hunting, fishing and gathering. They lived along river valleys for trapping.

Colonial wars

[edit]As both the French and English increased the number of their settlers in North America, their competition grew for control of the fur trade and physical territory. In addition, wars were carried out that reflected war in Europe. The lucrative eastern fur trade faltered with the general unrest, as French and English hostilities concentrated in the region between Québec and Port-Royal. Increasing sporadic fighting and raiding also took place on the lower Saint John River.