User:Tdl120300/sandbox

| This is a user sandbox of Tdl120300. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

| Tdl120300/sandbox | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scotoplanes globosa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Echinodermata |

| Class: | Holothuroidea |

| Order: | Elasipodida |

| Family: | Elpidiidae |

| Genus: | Scotoplanes Théel, 1882[1] |

| Species | |

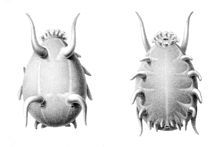

Scotoplanes is a genus of deep-sea sea cucumbers of the family Elpidiidae. Its species are commonly known as sea pigs.

Hi I am in Marine Biology and my favourite species is Greenland Sharks.

CO2 E=mc2

Farting as a defence against unspeakable dread[2]

- Bullet point

- Numbered bullet point

°≥±§•→←≠≈″¡¿†《》『』‽⅛²↘

Locomotion

[edit]Members of the Elpidiidae have particularly enlarged tube "feet" that have taken on a leg-like appearance, using water cavities within the skin to inflate and deflate thereby causing the appendages to move.[3] The "horns" on its back are also actually legs. Scotoplanes move through the top layer of seafloor sediment and disrupt both the surface and the resident infauna as it feeds.[4]

Ecology

[edit]Scotoplanes live on deep ocean bottoms, specifically on the abyssal plain in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans, typically at depths of over 1,200[5]–5,000 metres.[6] Some related species can be found in the Antarctic. Scotoplanes (and all deep-sea holothurians) are deposit feeders and obtain food by extracting organic particles from deep-sea mud. Scotoplanes globosa has been observed to demonstrate strong preferences for rich, organic food that has freshly fallen from the ocean's surface[7] and uses olfaction to locate preferred food sources such as whale corpses.[8] Scotoplanes, like many sea cucumbers, often occur in huge densities, sometimes numbering in the hundreds when observed. Early collections have recorded groups of up to 300-600 individuals. Sea pigs are also known to host different parasitic invertebrates, including gastropods (snails) and small tanaid crustaceans. [citation needed]

Scotoplanes, like other sea cucumbers, host parasitic and commensal organisms. For example, it provides a shelter to juvenile crabs, Neolithodes diomedeae. It is known that such relationship benefits the crabs because they can reduce risks of predation when they are under the shelter.[9]

Size

[edit]Scotoplanes can be as big as up to 4-6" (15 cm) long.[10]

Physiology

[edit]Scotoplanes are tiny and have their own defence mechanism to protect themselves from predators. Their skin contains a toxic chemical called holothurin which is poisonous to other creatures.

Like all echinoderms, Scotoplanes have a poorly developed respiratory system and they breathe from their anus. Their bodies are made for the deep seas and bringing them too close to the surface would cause them to disintegrate.[11]

Taxonomy

[edit]The genus includes the following species:[12]

A study done provides histologic findings that these deep-sea dwelling sea pigs are similar to other holothuroidea, though there are few notable differences: Most holothurians are sexually dioecious with sexes in separate individuals. Unlike other echinoderms, holothuroids possess only a single gonad. The water vascular system of holothuians is similar to other echinoderms, except the madreporite opens in the perivisceral coelom instead of in the external body wall.[13] In male Scotoplanes their aboral intestines have protozoa inside these cyst cavities.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ Théel, H (1886). "Report on the Holothurioidea dredged by HMS Challenger during the years 1873-76".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Sidoli, Mara (1996). "Farting as a defence against unspeakable dread". Journal of Analytical Psychology. 41 (2): 165–178. doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1996.00165.x. ISSN 1468-5922.

- ^ Hansen, B. (1972). "Photographic evidence of a unique type of walking in deep-sea holothurians". Deep-Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts. 19 (6): 461–462. Bibcode:1972DSRA...19..461H. doi:10.1016/0011-7471(72)90056-3.

- ^ Blake, James A.; Maciolek, Nancy J.; Ota, Allan Y.; Williams, Isabelle P. (2009-09-01). "Long-term benthic infaunal monitoring at a deep-ocean dredged material disposal site off Northern California". Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 56 (19–20): 1775–1803. Bibcode:2009DSRII..56.1775B. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.05.021.

- ^ Barry, James P.; Taylor, Josi R.; Kuhnz, Linda A.; De Vogelaere, Andrew P. (2016-10-01). "Symbiosis between the holothurian Scotoplanes sp. A and the lithodid crab Neolithodes diomedeae on a featureless bathyal sediment plain". Marine Ecology. 38 (2): e12396. doi:10.1111/maec.12396. ISSN 1439-0485.

- ^ Llano, George Biology of the Antarctic Seas III, Volume 11 of Antarctic research series, Volume 3 of Biology of the Antarctic seas, Issue 1579 of Publication (National Research Council (U.S.))) American Geophysical Union, 1967, p. 57

- ^ Miller, R. J.; Smith, C. R.; Demaster, D. J.; Fornes, W. L. (2000). "Feeding selectivity and rapid particle processing by deep-sea megafaunal deposit feeders: A 234Th tracer approach". Journal of Marine Research. 58 (4): 653. doi:10.1357/002224000321511061.

- ^ Pawson, DL; Vance, DJ (2005). "Rynkatorpa felderi, new species, from a bathyal hydrocarbon seep in the northern Gulf of Mexico (Echinodermata: Holothuroidea: Apodida)". Zootaxa. 1050: 15–20. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1050.1.2.

- ^ Barry, James P.; Taylor, Josi R.; Kuhnz, Linda A.; De Vogelaere, Andrew P. (2017). "Symbiosis between the holothurian Scotoplanes sp. A and the lithodid crab Neolithodes diomedeae on a featureless bathyal sediment plain". Marine Ecology. 38 (2): e12396. Bibcode:2017MarEc..38E2396B. doi:10.1111/maec.12396.

- ^ Bates, Mary (2014-06-16). "The Creature Feature: 10 Fun Facts About Sea Pigs". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- ^ Barry, James; Taylor, Josi; Kuhnz, Linda; De Vogelaere, Andrew (October 15, 2016). "Symbiosis between the holothurian Scotoplanes sp. A and the lithodid crab Neolithodes diomedeae on a featureless bathyal sediment plain". Marine Ecology. 38 (2): e12396. doi:10.1111/maec.12396.

- ^ MarineSpecies.org – Scotoplanes

- ^ a b LaDouceur, Elise E. B.; Kuhnz, Linda A.; Biggs, Christina; Bitondo, Alicia; Olhasso, Megan; Scott, Katherine L.; Murray, Michael (August 2021). "Histologic Examination of a Sea Pig (Scotoplanes sp.) Using Bright Field Light Microscopy". Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 9 (8): 848. doi:10.3390/jmse9080848.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

External links

[edit]- Scotoplanes article and photos on Echinoblog

- Sea pigs? Gross or cool? on Animal Planet website

- Sea Cucumbers: Holothuroidea – Sea Pig (scotoplanes Globosa): Species Accounts at Animal Life Resource

- [1] Neptune Canada "Sea Pig Slow Dance"

- Scotoplanes as a refuge for crabs

Further reading

[edit]Ruhl, Henry A., and Kenneth L. Smith, Jr. "Go to Science." Science Magazine: Sign In. Science., 23 July 2004. Web. 1 May 2015. [1]

Category:Holothuroidea genera Category:Elpidiidae Category:Taxa named by Johan Hjalmar Théel

- ^ Ruhl, Henry A.; Smith, Kenneth L. Jr. (23 July 2004). "Shifts in Deep-Sea Community Structure Linked to Climate and Food Supply". Science. 305 (5683): 513–515. Bibcode:2004Sci...305..513R. doi:10.1126/science.1099759. PMID 15273392. S2CID 29864283.

NEW SAND BOX FOR GREENLAND SHARK PROJECT:

Note** anything written in bold is my new contributions to the article. The stiff not in bold is existing information.

Description:

The Greenland shark is one of the largest living species of shark. Growing anywhere from 6.4m (21 ft) to 7.3m (24m) and weighing anywhere from 1000kg (2200lbs) to 1400kg (3100lbs). With the males typically being smaller than the females. The Greenland shark is a thickset species, with a short, rounded snout, small eyes, and very small dorsal and pectoral fins. The gill openings are very small for the species' great size.Coloration can range from pale creamy-gray to blackish-brown and the body is typically uniform in color, though whitish spots or faint dark streaks are occasionally seen on the back. Their coloration allows for them to blend in with their environmental surroundings (cryptic colouring), allowing them to approach prey without being detected.

Dentition:

When the Greenland shark feeds on larger animals (such as seals, or whale carcusses), they exhibit a rolling motion of the jaw. The Greenland shark typically has 48-52 teeth on their upper jaw. These teeth are very thin, sharp, and smooth. These teeth act as an anchor, pinning down the prey in which the shark is feeding on, while the bottom jaw cuts and rips massive chunks out of the prey. The 48–52 lower teeth are interlocking and are broad and square, containing short, smooth cusps that point outward. Teeth in the two halves of the lower jaw are strongly pitched in opposite directions.

Diet:

The Greenland shark is considered to be an apex predator. Their diet consists primarily of other fish; however, they have been observed actively hunting seals. Based on the prey that is found within their stomachs, it is indicated the type of active hunting patterns of the Greenland shark. Recorded fish prey have included smaller sharks, skates, eels, herring, capelin, Arctic char, cod, rosefish, sculpins, lumpfish, wolffish, and flounder. The smaller Greenland sharks where observed to eat mostly squid, small fish, and other small crustaceans and invertebrates, whereas the larger Greenland sharks feed on epibenthic and benthic species (such as rays, flat fish, crabs, shrimps) and some species were exhibited feeding on seals. The largest members of the species were also found with redfish in their stomach contents.

Due to the slow speeds of the Greenland shark, they hunt prey while they are asleep or resting. Using cryptic colouring, a defense mechanism that allows them to blend in with their surroundings, they approach the prey and are able to remain undetected. They are considered to be suction feeders as once they are close enough to their prey they will expand their buccal cavity, creating a suction that is too strong for the prey to escape, inhaling the prey (usually whole)

Greenland sharks have also been found with remains of seals, polar bears, moose, and reindeer (in one case an entire reindeer body) in their stomachs. The Greenland shark is known to be a scavenger, and is attracted by the smell of rotting meat in the water. The sharks have frequently been observed gathering around fishing boats. It also scavenges on seals.

Although such a large shark could easily consume a human swimmer, the frigid waters it typically inhabits make the likelihood of attacks on humans very low, and no cases of predation on people have been verified.

Movement:

The Greenland shark is an ectotherm, who is living in the deep sea, meaning the environment in which it lives in, is just above freezing. the Greenland shark has the lowest swim speed and tail-beat frequency for its size across all fish species, which most likely correlates with its very slow metabolism and extreme longevity. It swims at 1.22 km/h (0.76 mph), with its fastest cruising speed only reaching 2.6 km/h (1.6 mph). Because this top speed is only half that of a typical seal in their diet, biologists are uncertain how the sharks are able to prey on the faster seals. It is hypothesized that they may ambush them while they sleep.

Greenland sharks migrate annually based on depth and temperature rather than distance, although some do travel. During the winter, the sharks congregate in the shallows (up to 80° north) for warmth but migrate separately in summer to the deeps or even farther south. The species has been observed at a depth of 2,200 metres (7,200 ft) by a submersible investigating the wreck of the SS Central America that lies about 160 miles (260 km) east of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Daily vertical migration between shallower and deeper waters has also been recorded.

In August 2013, researchers from Florida State University caught a Greenland shark in the Gulf of Mexico at a depth of 1,749 m (5,738 ft), where the water temperature was 4.1 °C (39.4 °F). Four previous records of Greenland shark were reported from Cuba and the northern Gulf of Mexico. A more typical depth range is 0–1,500 m (0–4,900 ft), with the species often occurring in relatively shallow waters in the far north and deeper in the southern part of its range.

Other Behaviours:

The Greenland shark is often found with the copepod Ommatokoita elongata, attached to the Greenland sharks’ eyes. It was initially speculated that the Greenland shark and copepod were exhibiting a mutualistic relationship, as the copepod could use bioluminescence to attract prey towards the Greenland shark, however there is no way for certain to determine that any sort of mutualistic relationship is occurring. It has been discovered that the copepod damages the Greenland sharks’ eyes, leaving them almost completely blind. Since Greenland sharks do not depend on their eyesight as heavily as they do their scent, then the copepod blinding the shark does not seem to effect or lessen the life expectancy of the shark in anyway.

The shark occupies what tends to be a very deep environment seeking its preferable cold water (−0.6 to 12 °C or 30.9 to 53.6 °F) habitat.

When hoisted upon deck, it beats so violently with its tail, that it is dangerous to be near it, and the seamen generally dispatch it, without much loss of time. The pieces that are cut off exhibit a contraction of their muscular fibres for some time after life is extinct. It is, therefore, extremely difficult to kill, and unsafe to trust the hand within its mouth, even when the head is cut off. And, if we are to believe Crantz, this motion is to be observed three days after, if the part is trod on or struck.

— Henry William Dewhurst, The Natural History of the Order Cetacea (1834)

Reproduction :

Greenland sharks undergo internal fertilization. The eggs are fertilized inside the female shark, where they develop and are born alive (this process is called ovoviviparity). Greenland sharks give birth to around 10 offspring at one time, and due to the long lifespan of the Greenland shark, they could have anywhere from 200-700 pups in their lifetime. The gestation period is estimated to be anywhere between 8-18 years. About ten pups per litter is normal, each initially measuring some 38–42 cm (15–17 in) in length.[self-published source?] Within a Greenland shark's uterus, villi serve a key function in supplying oxygen to embryos. It is speculated that due to embryonic metabolism dealing with reproduction, this only allows for a limited litter size of around 10 pups.

- ^ Society, National Geographic (2011-08-25). "camouflage". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- ^ "Greenland shark | Size, Age, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-04-08.