User:Smolee3/Taoist Paradox

Taoist paradoxes are a series of paradoxes found in the writings of Taoist thinkers Laozi and Zhuangzi by Mozi, a Mohist thinker of the Spring and Autumn Period of China, and Yangxiong, a Confucian thinker of the Western Han Dynasty. They are: "All words are paradoxical" (all words fail to express the truth), "Learning is useless" (learning is not beneficial), "No defamation" (one should not rebut another person's words), and "Argumentation is not victorious" (no winner in an argument). Mozi and Yang Xiong logically analysed these paradoxes in their writings and used them to attack Taoist doctrine[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9].

contradict as much as possible

[edit]

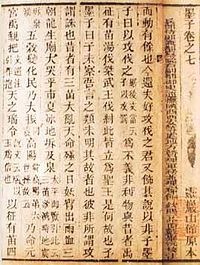

The expression "all speech is wrong" or "all speech fails to express the truth" has been used in the writings of Lao and Chuang to express the subtlety of the Tao (道), which broadly refers to the laws of the universe and everything in it.

Chuang Tzu mentions it in his book "Chuang Tzu - The Theory of Qi Matters": The Tao has not yet begun to have a seal, the words have not yet begun to have a constant, in order to be and there are boundaries, please say its boundaries: there is a left, there is a right, there is ethics, there is righteousness, there is a division, there is a debate, there is a competition, there is a fight, this is called the eight virtues. Outside of the Six Harmonies, the saints existed but did not care; within the Six Harmonies, the saints discussed but did not argue. In the Spring and Autumn Period, the sages discussed but did not debate the wishes of the late kings. Therefore, those who are divided, there are not divided; those who argue, there are not argued. He said: Why? The saints care, the public debate to show each other. Therefore, it is said that those who debate also have not seen also. The road is not called, the great debate is not spoken, the great benevolence is not benevolent, the great honesty is not classified, the great courage is not aggressive. The road is clear and not the road, the word debate but not as much as, benevolence often and not, clean and unbelieving, courageous and aggressive and not. The five gardens and a few to the square is carried out, so know stop what it does not know, to the end. Who knows not to speak and debate, not the way? If there can be known, this is called the House of Heaven. Note and not full, discretionary and not exhausted, but do not know its origin, this is called Plough Light. According to Zhuang Zi, great truths cannot be expressed in words alone (大辯不言), and expressing them in words will greatly reduce their original meaning (言辯而不及), thus leading to the reasoning that "all words cannot express the truth" (言盡悖). This further corresponds to the statement in Lao Tzu's book, Tao Te Ching - Guan Zhi Zi Zhang (觀玅章): The Way may be the Way, but it is not the Way. A name can be a name, but it is not a name. There is no name, the beginning of heaven and earth; there is a name, the mother of all things. Therefore, often nothing, want to see its wonderful; often have, want to see its mere. These two, the same out of a different name, the same metaphysical. The mystery of the mystery, the door of all wonders.

"If the truth of all things in heaven and earth is expressed in words, it is not the original truth; if the truth has a name, it is not the original truth (Tao can be a Tao, but it is not a Tao; a name can be a name, but it is not a name)". This means that the truth of all things in heaven and earth is formless, and it is difficult to express it in words.

However, Mozi, who was a thinker of the Mohist school of thought, attacked the saying that "words are all contradictory" in his writings "Mozi - Jing Shi" and "Mozi - Jing Shu Shi": The word is the most perverse of all, perverse, said in its words. ...... to, paradoxical, can not also. The words of the people can be, is not contrary, then there can be; the words of the people can not be, in order to when, will not be judged. According to Mozi, the expression "all words are contrary to the truth" is inherently fallacious. If the premise is that "all words cannot express the truth", then is the premise itself the truth?

He analysed the situation logically: assuming that "all statements fail to express the truth" as a premise, and that the result of the argument is true, then there are statements that express the truth, but are contradictory to his own expression, "the words are contradictory"; and assuming that "all statements fail to express the truth" as a premise, and that the result of the argument is false, then, according to the definition of the premise, "the words are contradictory" must be false, and yet the result is the same as the result of his own expression, so that "the words are contradictory" is true. However, if the result is the same as the result of one's own expression, then "the words are completely contradictory" becomes true. This is why Mozi defines "words are all paradoxical" as a paradox, and by extension, the Taoist doctrine is based on paradoxes, which are vague and mysterious, and cannot be correctly expressed.

Learning is not beneficial

[edit]

Learning is not beneficial, which translates into the vernacular as "learning is not beneficial", and is found in Laozi's work Tao Te Ching - Guan Jie Zhang (《道德經-觀玅章》), "Absolute Learning and No Worries" (絕學無憂) (if you stop learning, you will be free of worries and anxieties, "This way of interpreting the language can be called an understanding of Zhuangzi's great fallacy"), and is also quoted in later Daoist writings such as the Taiping Ching Leadership Book (太平清領書), which was compiled by Yu Ji (于吉)and Gong Chong (宫崇).

Lao Tzu's work "Tao Te Ching - Guan Jie Chapter" stated: If you give up wisdom for holiness, the people will benefit a hundredfold; if you give up righteousness for benevolence, the people will be filial and kind; if you give up profit for ingenuity, there will be no thieves and no robbers. These three things are not enough to make a text. Therefore, I want to have some attributes: to be plain and simple, to think little and desire little, and to study without worry. He thought that troubles were acquired in learning, and that every time there was a new knowledge, there was a new trouble and a new sin. Therefore, he appealed to the people to give up knowledge, and to give up everything that could be learned from learning, so that the people would return to simplicity and be free from sins and evils.

The Book of Taiping Qing Leaders, compiled by Yu Ji and Gong Chong, also states: Duh! Yelp! Though the six sons study every day, it is useless, and they are even more stupid, slightly similar to the ignorant people, why? The law of heaven and earth, the rise and fall of all things follow the people.

It means that even though one absorbs new knowledge day by day, one becomes more stupid and less ignorant than an ignorant person. The book explains it this way: the laws of heaven and earth are changing all the time, and when people learn something new, it soon becomes outdated and useless. Spending time to learn something that is destined to be useless, but using it in the formless and ever-changing laws, only makes them look stupid.

Yang Xiong, a Confucian thinker, was not convinced that "learning is not beneficial", and wrote an article in "Fayan - Learning and Conducting" to criticise it: Or he said: "Learning is not beneficial, such as quality?" I said, "I have not thought about it. If there are nine of them, the jade is wrong. If you don't, how can you use it? If you do not use it, how can you use it? If you use it and make a mistake, the quality is there; otherwise, you will not use it."

Yang Xiong's attack on those who say, "Learning is not beneficial," has not been thought through at all. If learning is not beneficial, how can the essence of a person be taken? He used the analogy of jade, which was originally a stone when it was developed, but had to be polished and refined in order to be made into a jade vessel. A knife can only be useful if it is sharpened, whereas jade is just a piece of stone without being sharpened and is useless. The same applies to human beings. Although they have good qualities, they cannot recognise them without learning and experience. Mozi had a different view.

In his writings, Mozi's "Mozi - Jing Shi" and "Mozi - Jing Shu Shi" attacked the saying that "learning is not beneficial": The benefit of learning is also said to be in the defamer. ...... Learning is also, in order not to know the learning of no benefit also. I'm not sure what I'm talking about, but I'd like to know what I'm talking about. The fact is that it is not beneficial to learn is also a teaching. The first thing I'd like to do is to teach you that it is not beneficial to learn, and to teach you that it is not! Mozi believed that learning is beneficial and those who say "learning is not beneficial" are misleading the public. He analysed it logically: if "learning is not beneficial" is true, then there must be teaching in order to learn, teaching is the cause, learning is the effect, and the two are interrelated, but there is no reason why teaching is beneficial and learning is not. However, Laozi taught the public that "learning is not beneficial", so that the public could learn that "learning is not beneficial", which is contradictory to the statement that "learning is not beneficial" and so "learning is not beneficial", and thus "learning is not beneficial" is definitely a paradox.

non-defamation

[edit]

Non-defamation, when translated into vernacular, means "one should not refute others", "one should not criticise others", "one should not argue", "one should not debate", which can be found in his book Zhuang Zi - The Theory of Qi Matter. Zhuang Zi - Qi Matter Theory (莊子-齊物論) was written by Zhuang Zi in response to the debating style of the Hundred Schools of Thought, and it expresses the idea that "one should not refute others".

Zhuangzi's work "Zhuangzi - The Theory of Qi Matter" stated: A great knowledge is leisurely, a small knowledge is idle; a great word is hot, a small word is zhanzhan. Their souls are intertwined when they sleep, and their minds are open when they feel, and they are in tune with each other, and their hearts are in a state of confusion every day. I am a specialist in the field of technology, and I am a specialist in the field of cellars. I am afraid of the small, but I am afraid of the large. His hair is like a machine, and he is the master of right and wrong; he stays like a curse, and he is the guardian of victory; he kills like autumn and winter, in order to say that his days are waning; he drowns what he has done, and cannot be restored; he is as disgusted as a silence, in order to say that he is in a state of old age; and he is so close to death that he cannot be restored to the sun. Joy, anger, sadness and happiness, anxiety, sighs and changes, Yao anonymous Kai state; music out of the virtual, steam into bacteria. The day and night are in front of each other, and there is no way to know what has sprung up. It has been, it has been! The daytime and nighttime are the same, and they are born from it! According to Zhuang Zi, the so-called famous debaters, who appear to speak with extraordinary power, are in fact more angry than reasonable, and are not forgiving of one's own reasoning. They use tricky words to explain their meaning, which makes their speech rapid. For the sake of debate, debaters have sleepless nights and spend their waking hours in arguments, coming into contact with their opponents and arguing their points all day long. At the same time, in order to defeat their opponents, they add traps to their speech, but they are also afraid of falling into the traps of their opponents' speech, and they are afraid all the time. The apologist will remain silent until he finds the flaws in his opponent's speech, but when he does, he will be aggressive. However, the truth is interpreted in different ways at different times. It is invisible and cannot be regulated, and the truth may even change so quickly that it is hard to know what to do next. He said that it was too difficult to advise debaters to give up arguing because the honour of distinguishing between right and wrong was too strong a temptation, and arguing over and over again would deplete one's true energy, and one would gradually lose interest in other things, like a dead person, and so would not be beneficial to oneself.

In addition, Zhuangzi also had other views on the Ru-Mo debate:

The words are not blown, the words are spoken. What they say is not yet determined. Do they have words? Is there a word for it? If they are different from fledglings, do they have a defence? Is there no defence? Is it true that there are truths and falsehoods in a hidden way? Is it true that words are hidden, but there is a right and a wrong? Is it not true that a word can be hidden, and a word can be hidden, and a word can be right and wrong? Is it not possible for a word to exist? The Tao is hidden in small successes, and the words are hidden in glory and splendour. Therefore, there is the right and wrong of Confucianism and Mozambique, to be what it is not and not what it is. If you want to be what you are not and not what you are, then there is nothing better than to be clear about it. Zhuangzi named Confucianism and Mohism as the two schools of thought which would not come to fruition. He thought that arguments were like the wind blowing, and that there were no certain criteria for the arguments of the debaters, so even if they argued with each other, what was the difference between the arguments of the two schools of thought? Even if they argue with each other, what is the difference between their arguments? The so-called Ru-Mo debate is nothing more than using one's own "right" to refute one's opponent's "wrong", and then using one's own "wrong" to refute one's opponent's "right".

In his writings, Mozi - Jing Shi (墨子-經下) and Mozi - Jing Shu Shi (墨子-經說下) refute the claim of "non-defamation": The non-defamatory ones are not, said in the Fufei. ...... is not defamatory, not his own defamation. The first thing I want to say is that I'm not going to be the one to do it. The same is true of the non-defamatory, which is the case with the non-defamatory. According to Mozi, there is a big problem with the phrase "non-defamation", and the key lies in the word "non-". The phrase "one should not refute others" is itself a refutation of the person who "refutes others", which is self-contradictory, and thus the inference is that "refutation" is itself irrefutable.

He analyses it logically: if the premise of "one should not refute others" is taken as the basis, then Zhuang Zi's "The Theory of Things" is itself a criticism of the debating style of the Hundred Schools of Thought, and Zhuang Zi's use of his self-confessed "yes" (non-defamation) to refute the "no" of his opponents (the Ru-Mo polemics) is a debate. Therefore, Zhuang Zi was basically slapping himself in the face, so it is a paradox.

No victory in defence.

[edit]

The phrase "辯無胜" (辯無勝) translates into the vernacular as "neither party to a debate can win" and "there can be no outcome to a debate", which can be found in his book ZHUANG Zi (莊子), "The Theory of Qi Matter" (齊物論). This argument is related to the term "non-defamation", and is directed at the style of debate among the Hundred Schools of Thought. Zhuang Zi argued that reasoning was formless and inexpressive, and could not be expressed in words, so debates would not be fruitful.

Zhuangzi's work "Zhuangzi - The Theory of Qi Matter" stated: It is not the other that is without me; it is not I that have nothing to take. And I am not aware of what I am doing, nor do I know what I am doing. And if there be a true master, he will not be the pupil of his pupil. It is possible to believe in oneself, but not to see its form, to have feelings without form. The hundred skeletons, the nine orifices, the six Tibetans, are all there, and who are my relatives? Who are my relatives? Do you have a personal interest in them? Are they all concubines? Are their subjects and concubines not enough to rule each other? Are they to be rulers and ministers? Is there a true ruler? If one seeks to obtain his love or not, it will not help to impair his truth. According to Zhuang Zi, reason is the law of the world, not a material thing, so it cannot be caught and touched. He used the human body as an analogy for reason, as there are bones, nine orifices and internal organs. However, which part is the master of the human body? Which one should be loved and cared for? Or should every part be cared for? Or is there a particular part that should be cared for? Or is it that every part is dominated? If every part of the body is dominated, then no part of the body should dominate the other parts, but should there still be a dominator? Or do different parts of the body take turns to be the master of the body? He said that if the body is functioning normally, there must be a master, but where is the master? But where is the master? Can this be debated? According to Zhuangzi, truth is scattered in heaven and earth and varies from time to time. People seem to grasp the truth in debates, but they have nothing to do with the real truth, so debates will not be fruitful. He also said: Now that I have debated with you, if you win against me, and if I do not win against you, what if I do, and what if I do not? If I am victorious over you, and if I am not victorious over you, am I right, and am I wrong? If I win, if I don't win, if I do, if I don't, if I do, if I don't? Is it all right, and is it all wrong? I and I cannot know each other. But if a man be darkened, who shall I make right? Who shall set him straight, but he who is with him? If I am with him, I will not be able to correct him! And if he is with him, what can he do? But if they are with me, they will not be righted! And who is different from me and from the other? And if it be different from me and if it be different from the other, then can it be corrected? And if you are with me and if you are with me, what can you do? If we are not the same as we are, we will not be able to do right! But if I and if I were not to know each other, would I wait for them?

Chuang Tzu's own analogy: even if Chuang Tzu himself debates with his opponent and wins the debate, it does not mean that Chuang Tzu's argument is wrong; if Chuang Tzu wins the debate with his opponent, and they all hold the same argument, does it mean that Chuang Tzu's argument is right? If a third party is asked to judge, he may share Zhuangzi's view, or he may share his opponent's view, or he may hold a different view from both Zhuangzi and his opponent, but in any case, the third party has become one of the debaters, and therefore cannot make an objective judgement. Therefore, the three parties to the debate have no way of knowing who is right and who is wrong.

In his writings, Mozi - Jing Shi (墨子-經下) and Mozi - Jing Shu Shi (墨子-經說下) refute the claim that "debate is not victorious": It is said that there is no victory in debate, but it is not appropriate to say that it is in the debate. ...... It is said that if it is not the same, then it is different. If it is the same, it may be called a dog, or it may be called a canine. If it is not the same, then it is different. If it is the same, then it is a dog, or it is a dog. The same thing is not true of the dog, but of the difference. The person who is defending the case is either saying yes or saying no, and the person who is defending the case is also winning. According to Murray, it must be wrong to say that "debates do not lead to results". If the premise is that "debates do not bear fruit", is the premise itself right or wrong? If "there is no victory in debate" is true, then Zhuangzi wins the debate, and if "there is no victory in debate" is false, then Zhuangzi loses the debate. However, if "there is no victory in debate" is true, then it contradicts the premise, and must be a paradox.

It is said that what people say is either the same or different. He used the analogy of a dog, which has two names, one for "dog" and the other for "canine". If two people debate on each of these names, they will find out that they are talking about the same animal. Another analogy is that if two people debate whether an animal is a cow or a horse, they will find out whether the animal is a cow or a horse or neither. Debates are inconclusive because no one is willing to debate. Whenever there is a debate, there is always a difference between right and wrong, and the one who holds the truth is the winner.

Take the theories in Mohist logic, that is: He, the proper name: each other. Each other is permissible: they stop at each other, and this stops at this. They may not: they and this also, and they may also be one another. Each other stops at each other. If they are one another, then they are one another and this is one another.

It means "they are equal to each other", "this is equal to this", "each other is equal to each other", "each other is not equal to each other", "each other is not equal to this".

| Mohist Logic | those | these | that stops at that (idiom); that stops at nothing | this is where it stops | Each other stops at each other. | neither one nor the other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| substitute into | cow | horse | Cow equals cow. | Horse equals horse. | Bulls and horses are equal to bulls and horses. | Bulls and horses are not equal to cows and horses are not equal to cows. |

| Modern Logic | A | B | A = A | B = B | AB = AB | AB ≠ A, AB ≠ B |

bibliography

[edit]- ^ 中國哲學簡史·後期墨家 的存檔,存档日期2007-12-16. 馮友蘭著

- ^ 《智者的邏輯》[permanent dead link] 秦美珠、陳文江著 圓神出版

- ^ 中央国家机关青年国学经典导读名家讲座第八讲 《墨子》[permanent dead link]

- ^ 论墨家对谬误学的贡献[permanent dead link] 刘邦凡著

- ^ 万千说法:理性的癌变——悖论 的存檔,存档日期2005-03-17. 张远山著

- ^ "古代墨家的辯論之道". Archived from the original on 2012-06-05. Retrieved 2008-04-26.

- ^ 白話齊物論 的存檔,存档日期2008-03-31.

- ^ 先秦哲学“辩无胜”与“辩有胜”之争的真理观意义(晋荣东)[permanent dead link]

- ^ 生活中的悖论破解法 的存檔,存档日期2008-02-15.

[[Category:Confucianism]] [[Category:Mohism]] [[Category:Philosophical logic]]