User:Paul August/Gorgons

To Do

[edit]- Wilk

- Versant

- Phinney

- Feldman

- Kantor, H. 1962. 'A Bronze plaque from Tell Tainat' Journal of Near-Eastern Studies 21, 93-117

Current text

[edit]New text

[edit]Mythology

[edit]Gorgon cry

[edit]The loud cry that came from the Gorgons—perhaps related to 'Gorgon' being derived from the Sanskrit garğ, with it's connotations of a growling beast—was also part of their mythology.[1]

The Hesiodic Shield of Heracles (c. late seventh–mid-sixth century BC), which describes Heracles' shield, has the Gorgons depicted on it chasing Perseus, with their shrill cry seemingly being heard emanating from the shield itself:

The Gorgons, dreadful and unspeakable, were rushing after him, eager to catch him; as they ran on the pallid adamant, the shield resounded sharply and piercingly with a loud noise.[2]

Pindar tells us that the cry of the Gorgons, lamenting the death of Medusa during their pursuit of Perseus, was the reason Athena invented the flute.[3] According to Pindar, the goddess:

wove into music the dire dirge of the reckless Gorgons which Perseus heard pouring in slow anguish from beneath the horrible snakey hair of the maidens ... she created the many-voiced song of flutes so that she could imitate with musical instruments the shrill cry that reached her ears from the fast-moving jaws of Euryale.[4]

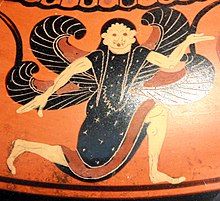

Nonnus, in his Dionysiaca, also has the fleeing Perseus "listening for no trumpet but Euryale's bellowing".[5] The desire to evoke this Gorgon cry may account for the typical distended mouth seen in Archaic Gorgon iconography.[6]

- ^ According to Howe, p. 212, "It is clear that some terrible noise was the originating force behind the Gorgon: a guttural, animal-like howl". Mack, p. 599, n. 5 notes that sound, "though only indirectly a feature of the face, was central to the conceptualization of Medusa's terrifying power". See also Feldman, pp. 487–488.

- ^ Most's translation of Hesiod, Shield of Heracles 230–233.

- ^ Gantz, p 20; Howe, pp. 210–211; Vernant, pp. 117, 125.

- ^ Svarlien's translation of Pindar, Pythian 12.7–11, 18–21. According to Vernant, p. 117, Pindar is saying here that the sound emitted by the pursuing Gorgons came "both from their maiden mouths and from the horrible heads of snakes associated with them".

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca 25.58; see also Dionysiaca 13.77–78, 30.265–266.

- ^ According to Howe, p. 211, the "reason that the Gorgon appears on monuments with a great distended mouth [was] to convey to the spectator the idea of a terrifying roar"; Vernant, p. 118, lists a "terrifying cry" and a "gaping grin" as one of several elements "linking the monstrous face of Gorgo to the warrior possessed by menos (murderous fury)".

[Howe etymologically connects the noises produced in the throat, such as "gurgling" and "gargling", with the story of Athena's invention of the flute: "When musical imagination refined that guttural sound implicit in the ancient and modern derivatives of “garğ,” it was produced not by plucking or beating, but with the breath blown into a narrow reed, a second throat attached to the real one".]

Mack, p. 599, n. 5

- It is worth noting that sound, though only indirectly a feature of the face, was central to the conceptualization of Medusa's terrifying power: the name 'Gorgon' derives from the Sanskrit stem garğ, meaning to roar or shriek; accounts of the monster describe her baleful dirge (oulios threnos) and piercing groan (eriklagton goon) (Pind., Pyth 12.6-8, 21), as well as the hiss (iachema) and furiously clattering teeth (menei d'echarasson odontas) of her snakes (Eurip. Her. fur. 881-2; Hesiod Aspis 231-5, where it is an image of snake-girdled, running gorgons that is made auditory); and her cry is the source for Athena's invention of flute-music (see Vernant, op. cit. [note 1], pp. 117-18, 123-7, with additional references; Frontisi-Ducroux, Du masque au visage, op. cit. [note 3], pp. 74-5).

Vernant

p. 117

- We know through Pindar (Pyth. 12.6ff.) that a piercing groan (eriklagtan goon) issues from the swift jaws of the Gorgons pursuing Perseus, and that these cries escape both from their maiden mouths and from the horrible heads of snakes associated with them.

p. 125

- But among all the musical instruments, the flute, because of its sounds, melody, and the manner in which it is played, is the one to which the Gorgon's mask is most closely related. The art of the flute—the flute itself, the way it is used, and the melody one extracts form it— was "invented" by Athena to "simulate" the shrill sounds she had heard escaping from the mouths of the Gorgons and their snakes. In order to imitated them, she made the song of the flute "which contains all sounds [pamphōnon Melos]" (Pind., Myth. 12.18ff.)

p. 127

- In addition to ... According to Xenophon, those who are possessed [cont.]

p. 128

- by certain divinities "have a more gorgonlike gaze, a more frightening voice, and more violent gestures." (Symptoms. 1.10). ... [Hecate,] like Gorgo, whom in certain respects she resembles closely enough to be sometimes invoked by her name (Hipp., Ref. her. 4.35),

- And indeed there is a reasonable foundation for the story that was told by the ancients about the flute. The tale goes that Athene found a flute and threw it away. Now it is not a bad point in the story that the goddess did this out of annoyance because of the ugly distortion of her features;

Apollodorus 1.4.2

- For Marsyas, having found the pipes which Athena had thrown away because they disfigured her face,1

- 1As she played on the pipes, she is said to have seen her puffed and swollen cheeks reflected in water. See Plut. De cohibenda ira 6; Athenaeus xiv.7, p. 616ef; Prop. iii.22(29). 16ff.; Ovid, Fasti vi.697ff.; Ovid, Ars Am. iii.505ff.; Hyginus, Fab. 165; Fulgentius, Mytholog. iii.9; Scriptores rerum mythicarum Latini, ed. G.H.Bode, i. pp. 40, 114 (First Vatican Mythographer 125; Second Vatican Mythographer 115). On the acropolis at Athens there was a group of statuary representing Athena smiting Marsyas because he had picked up the flutes which she had thrown away (Paus. 1.24.1). The subject was a favourite theme in ancient art. See Frazer, note on Paus. 10.29.3 (vol. ii. pp. 289ff.

Artemis / Mistress of Animals

[edit]- Vernant 1991

- p. 111

- In certain qualities she is close to Artemis.1 In the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia in Sparta, among the votive masks dedicated to the goddess (the young had to ware likenesses of these in the course of the agōgē in order to execute their mimetic dances), there are many that reproduce the monstrous and terrifying face of Gorgo.

- 1 Both have affinities with Potnia therōn, the great feminine divinity, mistress of the wild beasts and of wild nature, who proceeded them in the Creto-Mycenaean world and whose legacy each inherits in her own way by profoundly transforming it in the context of civic religion.

- In certain qualities she is close to Artemis.1 In the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia in Sparta, among the votive masks dedicated to the goddess (the young had to ware likenesses of these in the course of the agōgē in order to execute their mimetic dances), there are many that reproduce the monstrous and terrifying face of Gorgo.

- p. 111

- pp. 115–116

- The affinities between Gorgo and the Mistress of Animals, the Potnia, as Theodora Karagiora strongly emphasizes,13 are more promising. ...

- pp. 115–116

References

[edit]Sources

[edit]Ancient

[edit]- 790–800

- When you have crossed the stream that bounds the two continents, toward the flaming east, where the sun walks,......

- crossing the surging sea until you reach the Gorgonean plains of Cisthene, where the daughters of Phorcys dwell, ancient maids, [795] three in number, shaped like swans, possessing one eye amongst them and a single tooth; neither does the sun with his beams look down upon them, nor ever the nightly moon. And near them [the Graeae] are their three winged sisters, the snake-haired Gorgons, loathed of mankind, [800] whom no one of mortal kind shall look upon and still draw breath.

- 475–477

- ...your kidneys

- bleeding with your very entrails

- the Tithrasian Gorgons will rip apart.

- Henderson, p. 89, n. 52

- Teithras was an Attic deme, presumably inhabited by some formidable ladies.

- And to Sea ( Pontus) and Earth were born Phorcus, Thaumas, Nereus, Eurybia, and Ceto. Now to Thaumas and Electra were born Iris and the Harpies, Aello and Ocypete; and to Phorcus and Ceto were born the Phorcides and Gorgons, of whom we shall speak when we treat of Perseus.

- ...Now Perseus having declared that he would not stick even at the Gorgon's head, Polydectes ... ordered him to bring the Gorgon's head. So under the guidance of Hermes and Athena he made his way to the daughters of Phorcus, to wit, Enyo, Pephredo, and Dino; for Phorcus had them by Ceto, and they were sisters of the Gorgons, and old women from their birth. ... And [Perseus] flew to the ocean and caught the Gorgons asleep. They were Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa. Now Medusa alone was mortal; for that reason Perseus was sent to fetch her head. But the Gorgons had heads twined about with the scales of dragons, and great tusks like swine's, and brazen hands, and golden wings, by which they flew; and they turned to stone such as beheld them. So Perseus stood over them as they slept, and while Athena guided his hand and he looked with averted gaze on a brazen shield, in which he beheld the image of the Gorgon,5 he beheaded her. When her head was cut off, there sprang from the Gorgon the winged horse Pegasus and Chrysaor, the father of Geryon; these she had by Poseidon.6

- 5 Compare Ov. Met. 4.782ff.

- 6 Hes. Th. 280ff.; Ov. Met. 4.784ff., vi.119ff.; Hyginus, Fab. 151.

- So Perseus put the head of Medusa in the wallet (kibisis) and went back again; but the Gorgons started up from their slumber and pursued Perseus: but they could not see him on account of the cap, for he was hidden by it.

- And having become a surgeon, and carried the art to a great pitch, he not only prevented some from dying, but even raised up the dead; for he had received from Athena the blood that flowed from the veins of the Gorgon, and while he used the blood that flowed from the veins on the left side for the bane of mankind, he used the blood that flowed from the right side for salvation, and by that means he raised the dead.

- 1254–1257

- Dioskouroi

- Go to Athens and embrace the holy image of Pallas; [1255] for she will prevent them, flickering with dreadful serpents, from touching you, as she stretches over your head her Gorgon-faced shield.

- Dioskouroi

- 881–882

- the Gorgon child of Night, with a hundred hissing serpent-heads, Madness of the flashing eyes.

- 205–211

- Chorus

- I am glancing around everywhere. See the battle of the giants, on the stone walls.

- I am looking at it, my friends.

- Do you see the one [210] brandishing her gorgon shield against Enceladus?

- I see Pallas, my own goddess.

- Chorus

- 987–997

- Creusa

- Listen, then; you know the battle of the giants?

- Creusa

- Tutor

- Yes, the battle the giants fought against the gods in Phlegra.

- Tutor

- Creusa

- There the earth brought forth the Gorgon, a dreadful monster.

- Creusa

- Tutor

- [990] As an ally for her children and trouble for the gods?

- Tutor

- Creusa

- Yes; and Pallas, the daughter of Zeus, killed it.

- Creusa

- Tutor

- [What fierce shape did it have?

- Tutor

- Creusa

- A breastplate armed with coils of a viper.]

- Creusa

- Tutor

- Is this the story which I have heard before?

- Tutor

- Creusa

- [995] That Athena wore the hide on her breast.

- Creusa

- Tutor

- And they call it the aegis, Pallas' armor?

- Tutor

- Creusa

- It has this name from when she darted to the gods' battle.

- Creusa

- 1003–1015

- Creusa

- Two drops of blood from the Gorgon.

- Creusa

- Tutor

- And what power do they have over mortals?

- Tutor

- Creusa

- One is deadly, the other heals disease.

- Creusa

- Tutor

- In what did she hang them around the infant's body?

- Tutor

- Creusa

- In gold chains; and he gave them to my father.

- Creusa

- Tutor

- And when he died, they came to you?

- Tutor

- Creusa

- Yes; I wear them on my wrist.

- Creusa

- Tutor

- [1010] How is this double gift of the goddess accomplished?

- Tutor

- Creusa

- This one, which dripped from the hollow vein, at the slaughter—

- Creusa

- Tutor

- What is its use? What can it do?

- Tutor

- Creusa

- It wards off diseases and nourishes life.

- Creusa

- Tutor

- The second one you speak of, what does it do?

- Tutor

- Creusa

- [1015] It kills, as it is poison from the Gorgon serpents.

- Creusa

- 1048–1060

- Chorus

- Daughter of Demeter, goddess of the cross-ways, you who rule over assaults by night [1050] and day, guide this cup full of death against the one my queen sends it to—from the [1055] drops of the earth-born Gorgon, her throat cut, to the one who is grasping at the house of Erechtheus. May no other rule the city's households [1060] than one of the noble race of Erechtheus!

- Chorus

- 1261–1265

- Ion

- O Cephisus, her ancestor, with a bull's face, what a viper have you bred, or serpent that glares a deadly flame! She has dared all, she is no less than [1265] the Gorgon's blood, with which she was about to kill me.

- Ion

- 1417–1423

- Creusa

- Look; cloth that I wove as a child.

- Creusa

- Ion

- What sort? Girls weave many things.

- Ion

- Creusa

- Not completed, like a practice-work from the loom.

- Creusa

- Ion

- [1420] What appearance does it have? You will not catch me in this way.

- Ion

- Creusa

- A Gorgon in the middle threads of the robe.

- Creusa

- Ion

- O Zeus, what fate hunts me down!

- Ion

- Creusa

- And, like an aegis, bordered with serpents.

- Creusa

- They told how he [Perseus] came to Khemmis, too, when he came to Egypt for the reason alleged by the Greeks as well—namely, to bring the Gorgon's head from Libya—and recognized all his relatives; and how he had heard the name of Khemmis from his mother before he came to Egypt. It was at his bidding, they said, that they celebrated the games.

- Next to these along the coast are the Machlyes, who also use the lotus, but less than the aforesaid people. Their country reaches to a great river called the Triton,1 which empties into the great Tritonian lake, in which is an island called Phla. It is said that the Lacedaemonians were told by an oracle to plant a settlement on this island.

- Thus from Egypt to the Tritonian lake, the Libyans are nomads that eat meat and drink milk; for the same reason as the Egyptians too profess, they will not touch the flesh of cows; and they rear no swine.

- 270–282

- And again, Ceto bore to Phorcys the fair-cheeked Graiae, sisters grey from their birth: and both deathless gods and men who walk on earth call them Graiae, Pemphredo well-clad, and saffron-robed Enyo, and the Gorgons who dwell beyond glorious Ocean [275] in the frontier land towards Night where are the clear-voiced Hesperides, Sthenno, and Euryale, and Medusa who suffered a woeful fate: she was mortal, but the two were undying and grew not old. With her lay the Dark-haired One1 in a soft meadow amid spring flowers. [280] And when Perseus cut off her head, there sprang forth great Chrysaor and the horse Pegasus who is so called because he was born near the springs2 of Ocean; ...

- 1 i.e.Poseidon.

- 2 pegae

- And again, Ceto bore to Phorcys the fair-cheeked Graiae, sisters grey from their birth: and both deathless gods and men who walk on earth call them Graiae, Pemphredo well-clad, and saffron-robed Enyo, and the Gorgons who dwell beyond glorious Ocean [275] in the frontier land towards Night where are the clear-voiced Hesperides, Sthenno, and Euryale, and Medusa who suffered a woeful fate: she was mortal, but the two were undying and grew not old. With her lay the Dark-haired One1 in a soft meadow amid spring flowers. [280] And when Perseus cut off her head, there sprang forth great Chrysaor and the horse Pegasus who is so called because he was born near the springs2 of Ocean; ...

The Shield of Heracles (Aspis Hērakleous)

- The head of a terrible monster, the Gorgon covered his whole back;

- 229–237

- Perseus himself, Danae’s son, was outstretched, and he looked as though he were hastening and shuddering. The Gorgons, dreadful and unspeakable, were rushing after him, eager to catch him; as they ran on the pallid adamant, the shield resounded sharply and piercingly with a loud noise. At their girdles, two serpents hung down, their heads arching forward; both of them were licking with their tongues, and they ground their teeth with strength, glaring savagely. Upon the terrible heads of the Gorgons rioted great Fear.

Fr 294 [= 343 MW]

- 294 (343 MW) Gal. De placitis Hippocr. et Plat. III 8.11–14 (I p. 226.4–22 De Lacy) = Chrysippus Fr. 908 (SVF II p. 257.10–28)

- 294 Galen, On the Opinions of Hippocrates and Plato

- ... [Metis] made the aegis, Athena’s army-frightening breastplate:

- together with that [Zeus] bore her, wearing her warlike armor.

- ^ LSL ὀξύς A.II.3.

- ^ LSJ λιγύς.

- 5.738–742

- About her shoulders she flung the tasselled aegis, fraught with terror, all about which Rout is set as a crown, [740] and therein is Strife, therein Valour, and therein Onset, that maketh the blood run cold, and therein is the head of the dread monster, the Gorgon, dread and awful, a portent of Zeus that beareth the aegis.

- 8.349

- But Hector wheeled this way and that his fair-maned horses, and his eyes were as the eyes of the Gorgon [Γοργοῦς] or of Ares, bane of mortals.

- 11.32–37

- And he took up his richly dight, valorous shield, that sheltered a man on both sides, a fair shield, and round about it were ten circles of bronze, and upon it twenty bosses of tin, [35] gleaming white, and in the midst of them was one of dark cyanus. And thereon was set as a crown the Gorgon, grim of aspect, glaring terribly, and about her were Terror and Rout.

- 15.309–310

- Then the Trojans drave forward in close throng, and Hector led them, advancing with long strides, while before him went Phoebus Apollo, his shoulders wrapped in cloud, bearing the fell aegis, girt with shaggy fringe, awful, gleaming bright, that the smith [310] Hephaestus gave to Zeus to bear for the putting to rout of warriors; this Apollo bare in his hands as he led on the host.

- 21.400–402

- [400] So saying he smote upon her tasselled aegis—the awful aegis against which not even the lightning of Zeus can prevail—thereon blood-stained Ares smote with his long spear.

- 11.630–37

- And I should have seen yet others of the men of former time, whom I was fain to behold, even Theseus and Peirithous, glorious children of the gods, but ere that the myriad tribes of the dead came thronging up with a wondrous cry, and pale fear seized me, lest [635] august Persephone might send forth upon me from out the house of Hades the head of the Gorgon, that awful monster. “Straightway then I went to the ship and bade my comrades themselves to embark, and to loose the stern cables.

- 13.77–78

- Mycalessos with broad dancing-lawns, named to remind us of Euryale’s throatc

- c Euryale, a Gorgon; Nonnos derives the town’s name from the monster’s roar, μυκηθμός, μυκάομαι.

- Mycalessos with broad dancing-lawns, named to remind us of Euryale’s throatc

- 25.53–58

- Perseus fled with flickering wings trembling at the hiss of mad Sthenno’s hairy snakes, although he bore the cap of Hades and the sickle of Pallas, with Hermes’ wings though Zeus was his father; he sailed a fugitive on swiftest shoes, listening for no trumpet but Euryale’s bellowing

- 30.265–266

- Have you seen the eye of Sthenno which turns all to stone, or the bellowing invincible throat of Euryale herself?

- 40.227–233

- The double Berecyntian pipes in the mouth of Cleochos drooned a gruesome Libyan lament, one which long ago both Sthenno and Euryale with one many throated voice sounded hissing and weeping over Medusa newly gashed, while their snakes gave out voice from two hundred heads, and from the lamentations of their curling and hissing hairs they uttered the “manyheaded dirge of Medusa.”a

- a Pindar, Pyth. xii. 23 gives this origin of the tune called πολυκέφαλος—πολλᾶν κεφαλᾶν νόμον, the tune of many heads.

- The double Berecyntian pipes in the mouth of Cleochos drooned a gruesome Libyan lament, one which long ago both Sthenno and Euryale with one many throated voice sounded hissing and weeping over Medusa newly gashed, while their snakes gave out voice from two hundred heads, and from the lamentations of their curling and hissing hairs they uttered the “manyheaded dirge of Medusa.”a

- There are also represented nymphs bestowing upon Perseus, who is starting on his enterprise against Medusa in Libya, a cap and the shoes by which he was to be carried through the air. There are also wrought the birth of Athena, Amphitrite, and Poseidon, the largest figures, and those which I thought the best worth seeing.

- At Olympia a gilt caldron stands on each end of the roof, and a Victory, also gilt, is set in about the middle of the pediment. Under the image of Victory has been dedicated a golden shield, with Medusa the Gorgon in relief. The inscription on the shield declares who dedicated it and the reason why they did so. It runs thus:

- “The temple has a golden shield; from Tanagra

- The Lacedaemonians and their allies dedicated it,

- A gift taken from the Argives, Athenians and Ionians,

- The tithe offered for victory in war."

- This battle I also mentioned in my history of Attica,1 Then I described the tombs that are at Athens.

- 1 See Paus. 1.29.

- On the shield of Agamemnon is Fear, whose head is a lion's.

- There is at Tegea another sanctuary of Athena, namely of Athena Poliati (Keeper of the City) into which a priest enters once in each year. This sanctuary they name Eryma (Defence) saying that Cepheus, the son of Aleus, received from Athena a boon, that Tegea should never be captured while time shall endure, adding that the goddess cut off some of the hair of Medusa and gave it to him as a guard to the city.

Phythian

- 10.46–48 (Svarlien)

- ...[Perseus] killed the Gorgon, and came back bringing stony death to the islanders, the head that shimmered with hair made of serpents.

- 12.7–11

- [07] Παλλὰς ἐφεῦρε θρασειᾶν <Γοργόνων>

- [08] οὔλιον θρῆνον διαπλέξαισ᾿ Ἀθάνα·

- [09] τὸν παρθενίοις ὑπό τ᾿ ἀπλάτοις ὀφίων κεφαλαῖς

- [10] ἄιε λειβόμενον δυσπενθέι σὺν καμάτῳ,

- [11] Περσεὺς ὁπότε τρίτον ἄυσεν κασιγητᾶν μέρος

- 12.7–11 (Race)

- [07] which Pallas Athena once invented

- [08] by weaving into music the fierce Gorgons’ deathly dirge

- [09] that she heard pouring forth from under the unapproachable

- [10] snaky heads of the maidens in their grievous toil,

- [11] when Perseus cried out in triumph as he carried the third of the sisters,

- 12.7–11 (Svarlien)

- ... Pallas Athena discovered when she wove into music the dire dirge of the reckless Gorgons which Perseus heard [10] pouring in slow anguish from beneath the horrible snakey hair of the maidens, when he did away with the third sister

- 12.18–21

- [18] ... ἀλλ᾿ ἐπεὶ ἐκ τούτων φίλον ἄνδρα πόνων

- [19] ἐρρύσατο παρθένος αὐλῶν τεῦχε πάμφωνον μέλος,

- [20] ὄφρα τὸν ε[Ε]ὐρυάλας ἐκ καρπαλιμᾶν [eager, ravenous][1] γενύων

- [21] χριμφθέντα σὺν ἔντεσι μιμήσαιτ᾿ ἐρικλάγκταν γόον [shrill cry].

- 12.18–21 (Race)

- [18] ... But when she [Athena] had rescued her beloved hero from

- [19] those toils, the maiden composed a melody with every sound for pipes,

- [20] so that she might imitate with instruments the echoing wail

- [21] that was forced from the gnashing jaws of Euryale.

- 12.18–21 (Svarlien)

- ... But when the virgin goddess had released that beloved man from those labors, she created the many-voiced song of flutes [20] so that she could imitate with musical instruments the shrill cry that reached her ears from the fast-moving jaws of Euryale.

- 12.22–24

- [22] εὗρεν θεός· ἀλλά νιν εὑροῖσ᾿ ἀνδράσι θνατοῖς ἔχειν,

- [23] ὠνύμασεν κεφαλᾶν πολλᾶν νόμον,

- [24] εὐκλεᾶ λαοσσόων μναστῆρ᾿ ἀγώνων,

- 12.22–24 (Race)

- [22] The goddess invented it, but invented it for mortals

- [23] to have, and she called it the tune of many heads,

- [24] famous reminder of contests where people flock,

- 12.22–24 (Svarlien)

- The goddess discovered it; but she discovered it for mortal men to have, and called it the many-headed strain, the glorious strain that entices the people to gather at contests,

- ^ LSJ καρπάλι^μος.

Modern

[edit]Baltzoi

[edit]- Baltzoi, Sophia. "The Birth of the Tragic Mask through Ritual Practices" [unpublished draft?]

Belson 1981

[edit]p. 8 n. 1

- It is beyond the scope of this study to explore the many theories advanced regarding the source and significance of the gorgoneion motif. A number of scholars ...

p. 187 ff

- Gorgon Versus Gorgoneion:

Bremmer 2006

[edit]- s.v. Gorgo 1

- Female monster in Greek mythology. According to the canonical version of the myth (Apollod. 2,4,1-2), Perseus must get the head of Medusa, the mortal sister of Sthenno and Euryale (Hes. Theog. 276f.; POxy. 61, 4099), the daughters of Phorcys and Ceto (cf. Aeschylus' drama Phorcides, TrGF 262). The three sisters live on the island of Sarpedon in the ocean (Cypria, fr. 23; Pherecydes FGrH 3 F 11), although Pindar (Pyth. 10,44-48) located them among the Hyperboraeans ( Hyperborei). Their connection to the sea is still apparent in Sophocles (TrGF 163) and Hesychius (s.v. Gorgides). The Gorgos' terrifying shape (snake hair, fangs) transforms into stone whoever looks at them (their ugliness was so notorious that Aristoph. [Ran. 477] referred to the women of the Athenian deme Teithras as Gorgones). In the divine battle against the Titans, Athena also kills a G., whose blood was later attributed with the power to heal as well as to poison (Eur. Ion 989-991; 1003ff.; Paus. 8,47,5; Apollod. 3,10,3). With the aid of Athena, Hermes, and the Nymphs, who equipped him with winged sandals, Hades' helmet of invisibility, and a sickle (hárpē), Perseus is able to decapitate Medusa in her sleep (Pherecydes FGrH 3 F 11). From her neck rise Chrysaor [4] and the winged horse Pegasus. Perseus is pursued by Medusa's sisters, but he escapes and, in the end, turns his enemy Polydectes to stone by using G.'s head.

- The myth was already known to Hesiodus (Theog. 270-282) and shows oriental influences: the iconography of the G. has borrowed traits from Mesopotamian Lamaštu. Perseus saves Andromeda in Ioppe-Jaffa (Mela 1,64), and an oriental seal shows a young hero holding a hárpē and seizing a demonic creature [1. 83-87]. In Etruria, Perseus' adventure was already popular in the 5th cent. [3]. Roman authors like Ovidius (Men. 4,604-5,249) ─ who change Medusa into a stunningly beautiful young girl ─ and Lucan (9,624-733) focussed in particular on the frightening head of Medusa [cf. 4].

- In Mycenae, Perseus was seen in the context of initiation. His killing of Medusa reflects the testing of young warriors [2]. In fact, the descriptions of G.'s head recall certain elements of the archaic battle vehemence: the horrifying appearance, broad grin, grinding teeth, and powerful battle screams [6]. The popularity of G.'s head, the Gorgoneion, as attested on Athena's aegis and on warriors' shields (as early as Hom. Il. 5,741; 11,35-37) as well as in Aristoph. Ach. 1124, indicates the frightening effect and the protection of the Delphic omphalós (Eur. Ion 224) and the Delian thēsaurós (thesauros: IG XIV 1247) by the Gorgos. The myth of Perseus and Medusa is therefore an important example of the complex interrelation of narrative and iconographic motifs between Greece and the Orient during the archaic period.

- Bibliography

- 1 W. Burkert, The Orientalizing Revolution, 1992

- 2 M. Jameson, Perseus, the Hero of Mykenai, in: R. Hägg, G. Nordquist (ed.), Celebrations of Death and Divinity in the Bronze Age Argolid, 1990, 213-230

- 3 I. Krauskopf, S.-C. Dahlinger, s.v. G., Gorgones, LIMC 4.1, 285-330

- 4 I. Krauskopf, s.v. Gorgones (in Etrurien), LIMC 4.1, 330-345

- 5 O. Paoletti, s.v. Gorgones Romanae, LIMC 4.1, 345-362

- 6 J.-P. Vernant, Mortals and Immortals, 1991, 111-149.

- Bibliography

Bremmer 2015

[edit]- s.v. Gorgo/Medusa

- Female monsters in Greek mythology. According to the canonical version of the myth (Apollod. 2. 4. 1–2) Perseus (1) was ordered to fetch the head of Medusa, the mortal sister of Sthenno and Euryale; through their horrific appearance these Gorgons turned to stone anyone who looked at them. With the help of Athena, Hermes, and nymphs, who had supplied him with winged sandals, Hades' cap of invisibility, and a sickle (harpē) Perseus managed to behead Medusa in her sleep; from her head sprang Chrysaor and the horse Pegasus. Although pursued by Medusa's sisters, Perseus escaped and, eventually, turned his enemy Polydectes to stone by means of Medusa's head.

- Hesiod (Theog. 270–82) already knows the myth which shows oriental influence: the Gorgons' iconography has been borrowed from that of Mesopotamian Lamashtu; Perseus saved Andromeda in Ioppe-Jaffa, and an oriental seal shows a young hero seizing a demonic creature whilst holding a harpē. Gorgons were very popular—often with an apotropaic function, as on temple-pediments—in Archaic art, which represented them as women with open mouth and dangerous teeth, but in the 5th cent. they lost their frightening appearance and became beautiful women; consequently, the myth is hardly found in art after the 4th cent. BCE.

Burkert 1995

[edit]p. 83

- As has often been discussed, Lamashtu shares a whole range of characteristics with the Greek Gorgon.16

p. 85

- The connection between the Perseus-Gorgon myth and the Semitic East ... One of these [connections with the epic texts such as Gilgamesh] is the slaying of Humbaba by Gilgamesh and Enfiku, a scene which in turn is one of the models for the representation of Perseus killing the Gorgon (Figure 6).

Carpenter

[edit]pp. 134–139

Carter 1987

[edit]p. 355

- Early in the second millennium B.C., a remarkable figure appeared in Mesopotamian iconography (fig. 1). He wears a cap of hair like an overturned bowl, and his lips are pulled back in a wide grimace. From each side of his nose, deep furrows run down his face and around the corners of his mouth, then curl outward at his jawline in spirals. His grimace and the S-shaped furrows around his mouth identify him immediately.

- Terracotta masks dedicated in the Sanctuary of Artemis Ortheia at Sparta more than a thousand years later present equally grotesque faces, cheeks furrowed by deep S-shaped grooves and teeth bared (figs. 2-3). Several scholars, pointing out the similarity between the grotesque faces from Mesopotamia and Sparta, have assumed Near Eastern prototypes for the Spartan masks.1

- 1 Barnett 147-48; SP 50; J. Boardman, The Greeks Overseas (London 1980) 77.

p. 360

- Elsewhere in Greece, only Tiryns has produced life-sized terracotta masks. The fragments ... (ca. 750-650), and thus the Tiryns masks may be earlier than or contemporary with the first Spartan masks. ... As described by G. Karo,

- [they have a] broad face with ...

- While the Tiryns masks are clearly not dependent on Spartan models, they may derive from the same or similar prototypes as the Spartan furrowed grotesques. We must now ask what the prototypes were.

Chase 1902

[edit]p. 73

- The Gorgon upon the shield of Athena is twice mentioned by Euripides,2 and the same device is frequently referred to by Anstophanes.3

p. 75

- We are now in a position to discuss the most important part of our evidence, namely, notices of devices actually in use during the historical period of Greek civilization. Here, strangely enough, we find no mention of purely decorative emblems, and but few references to terrible emblems, for the gorgoneion in a scholium to Aristophanes5 and in the Anthology6 cannot be regarded as very sure or very weighty evidence. The only explanation which I can offer for this phenomenon is that such devices were so common as not to cause remark, the practice of the vase painters, who employ these classes of devices more commonly than any other, seems to me sufficient [cont.]

p. 76

- to prove that decorative and "terrible" emblems must have been in very common use.

p. 79

- Before ... On the whole I am inclined to believe that [vase painters in their depictions of shield emblems] followed very closely the practice of their time, and that the part to be assigned to invention is exceedingly small. This I believe for several reasons ... The constant recurrence of the commoner devices—the bull's head, the gorgoneion, the lion, the serpent, the tripod, can hardly be explained except upon the supposition that these devices were in constant and widespread use throughout the whole period of Greek civilization.

p. 95

- XVII. BALLS (two) AND GORGONEION. ... Amphora ...shields of Ajax and Achilles playing with pessi.

- ...

- XXVII. BALLS (two) AND GORGONEION AND SERPENTS (two). ... Amphora (Munich 1295); on Boeot. shield of warrior carrying comrades (Ajax?).

p. 106

- CXIX. GORGONEION. Mel. — 1. AMphora ... 2. Cylix ... [cont.]

P. 107

- ... — 39 ... on shield of Athena.

- CXX. GORGONEION (projecting from shield) Amphora ... on shield of Achilles.

- CXXI. GORGONEION (projecting from shield) AND RAYS. ... Fragment od situla (Naples, 2883; ) ... on shield of Enceladus.

- CXXII. GORGONEION AND WREATH (laurel). ... Volute crater (Naples, 2421); on shield of warrior fighting with Amazons.

- CXXIII. GORGONEION AND TRISKELE. ... Amphora ... on shield of Athena.

- GORGONEION AND BALLS (two). See No. XVII.

- CXXIV. GORGONEION AND LION AND SERPENT. ... Amphora ... on Boeot. shield of warrior.

- CXXV. GORGONEION AND PANTHERS (four) AND ROSETTES (two) ... Amphora ... on Boeot. shield of Ajax.

p. 108

- GORGONEION AND BALLS (two) AND SERPENTS (two). See No. XXVII

Cook 1940

[edit]- (a) The aigis and Gorgórneion of Athena.

- On the primary significance of the Gorgóneion there has been much rash speculation. Scholars ancient and modern have elaborated not a few mutually destructive hypothesis. ... [cont.]

- including ... Finally, H. J. Rose16 ...

- Be that as it may, the Gorgon's head, thanks to the humanizing tendency of Greek art, had an evolution of its own from lower to higher forms1 The archaic type (fig. 662)2 ...

- Fig. 662

- 2 An antefix of terracotta found on the Akropolis at Athens. Lips, tongue, gums, and earrings are painted dark-red; hair snakes, and pupils of eyes, black; face, buff. Seven fragments from a single mold survive, and date from the second half of the s vi B.C.

- The middle type (fig. 663)1 ...

- The beautiful type ...

- Fig. 665

- In any case once introduced [the beautiful type], the new type ran through a whole succession of phases, becoming sinister (fig. 665)1, pathetic (ig. 666)2, and ultrpathetic (fig. 667)3, but at last tranquilized [cont. p. 853]

- 1 The Medusa Rondanini ... Apart from the cold and cruel beauty of this face, the sculptor has imported a fresh element of interest in the pair of small wings attached to the head. Buoyed on these, with her concentrated stare and half-open mouth, Medousa hovers before us like some keen-eyed maleficent night-bird.

- [Cont. from p. 851] and dignified by death (fig. 668)1 ...

- The entire range of these modifications could be illustrated by a sequence of Greek and Roman coin-types, of which a few samples are here given (figs. 672-693)5 ...

- 5 Fig. 672 a silver tetradrachm of Athens 510-507 B.C. ...

- Fig. 673 a bronze coin of Olbia, ...

- Fig. 674 a bronze heilitron of Katarina c. 413 B.C. ...

- [cont.]

- Archaic Type, without snakes.

- [Figs. 672–677]

- Archaic Type, with snakes.

- [Figs. 678, 679]

- Transition to Middle Type.

- [Figs. 680–682]

- Middle Type.

- [Figs. 683–686]

- Beautiful Type.

- [Figs. 687–690]

- Assimilation of Helios to the Gorgon.

- [Figs. 691–693]

- Fig. 675 a billon statér of Lesbos c. 550-440 B.C. ...

- Fig. 676 a silver statér of Neapolis in Macedonia c. 500-411 B.C. ...

- ...

- Fig. 693 a silver drachm (?) of Rhodes c. 87-84 B.C. ...

Faraone

[edit]- It would be possible ... and are designed to operate as "terror masks", much like gorgoneia. The use of gorgoneia in Greek architecture, as well as on shields and ships, is most probably apotropaic in origin, and their appearance on archaic temples in particular may derive from an earlier Italic tradition of using human-head antefixes.16

Feldman [= Howe] 1965

[edit]p. 487

- In addition, as was demonstrated in the former article, the etymology of the name Gorgo vividly bears out Homer's pointed epithets, especially as they pertain to noise. Its root which in Sanskrit appears as garğ and occurs in numerous forms in Indo-European languages, is defined as a gurgling, guttural sound, sometimes human, sometimes animal, perhaps closest to the grrr of a growling beast. From her [cont.]

p. 488

- earliest illustrations we find also that Gorgo's mouth is always open wide, and indeed, she was not to close it for centuries. At the heart of Gorgo's myth was this blasting, grrrowling roar, asonant terrorism around which was enfolded the gorgoneion, The Blasting Thing, a head to give the cry substance. In due time there gradually was attached to it a Gorgo, A Blaster or Roarer, a body to give the thing mobility and dramatic action.

Fowler

[edit]p. 254

- As often with the mythical geography of the edges of the world, there is confusion about the location of [Perseus' encounter with the Gorgons]. In He's. Th. 270-5, the Graiai, Gorgons, and Hesperides all live in the west, near Okeanos' springs (πηγαί, whence Pegasus, 282).

Gantz

[edit]p. 20

- Unlike the Graiai, the Gorgons are from the beginning (in Hesiod) three in number (Th 274-83). Hesiod names them Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa, and places them toward the edge of night, beyond Okeanos, near the Hesperides, in other words to the far west (he does not say whether the Graiai lived near them). Of the three, steno and Euryale are immortal and ageless, but Medousa is mortal (Hesiod offers no explanation of this odd situation). She alone mates with Poseidon (assuming Kyanochaites is here as elsewhere, an epithet of the sea god), and after her beheading by Perseus, Chrysaor and the horse Pegasos spring forth from her neck. ...

- In contrast to the Theogony, Homer, although he describes several Gorgon heads on bucklers (e.g. Il 11.36-37) and conjures up another to frighten Odysseus in the Nekuia (Od 11.633-35), never alludes to the tale of Medusa, save in Iliad 5, where the description of Zeus' aegis worn by Athena includes the Gorgon head customarily donated by Perseus (Il 5.738-42). ... The Aspis offers a typically garish portrait: Gorgons with twin snakes ... wrapped around their wastes ... and possibly a vague reference to snakes for hair (Aspis 229-37). Snaky locks are in any case well attested by Pindar (Py 10.46-48; 12.9-12), and here again Medousa's head lithifies, while Euryale's lament becomes the model for the song of the flute. In Pythian 10, we also see Perseus journeying to the land of the Hyperboreans in the far north on his quest for the head; the Gorgons may or may not have been located there. For Aeschylus, we must again be content with the description in Prometheus Desmotes, since there are no relevant fragments from the Phorkides. As noted above, his Gorgons live near their sister Graiai to the far east; they have wings and snaky hair, and no mortal can look upon them and live (PD 798-800). This last detail suggests that Aeschylus believed all three sisters could turn men to stone, but he may be exaggerating for effect, or perhaps he refers to their generally ferocious character. The tale that Medousa was once beautiful, and fell prey to Athena's anger by mating with Poseidon in the goddess' temple, first appears in Ovid (Met 4.790-803); something of the same sort also surfaces in [cont.]

p. 21

- Apollodorus, who says that Medousa wished to rival Athena in beauty (ApB 2.4.3). Such an idea may have developed at some late point in time to dignify Posiedon's union with the Gorgon; certainly it will not explain the equally hideous condition of her two sisters.

- Artistic representations of Gorgons are much too abundant to list in detail here, ... On a Boiotian relief amphora of c. 650 B.C., a figure in traveling garb cuts off the head of a female represented as a Kentauros (Louvre CA 795).25 The attitude of the beheader, with face averted from his victim, seems not only to guarantee that this is an early Medousa, but to offer our earliest evidence for the Gorgon's perilous qualities. On the contemporary Protoattic Eleusis Amphora, the sisters appear as monstrous (albeit shapely) inset-faced creatures with no wings but distinct snakes around their heads (Eleusis, no #). By the time of the name vases of the Nessos and Gorgon Painters of Athens (end of the seventh century: Athens 1002, Louvre E874), canonical features, such as the tripartite nose and lolling tongue (perhaps developed in Corinthian painting), are basically in force; for the wings and snakes there is also a slightly earlier ivory relief from Santos depicting the decapitation (Samos E 1). ... We find this composition [with Pegasus and Chrysaor] ... on the famous Medousa pediment from the Temple of Artemis on Kerkyra (no #), where the wings and snakes are both in evidence. In this latter example, the two snakes knotted around her waist repeat the image found in the Apsis and seen again in Attic Black-Figure of the early sixth century.

p. 84

- Of all Athena's attributes, the most curious is surely the aegis. ... From Iliad 15 we learn that Hephaistos made it for Zeus (Il 15.309-10: cf He's fr 343 MW, where Metis makes it for Athena)., ... In Iliad 5 Athena clearly dons it as a piece of clothing (Il 5.738-42x), and in Iliad 21 she is again wearing it, a defense that not even the thunderbolt can pierce, when Ares attacks her (Il 21.400-401.

p. 85

- From the description in Iliad 5 we learn that [the aegis] was decorated with a Gorgon head; Medusa is not specifically mentioned (Il 5.741-42). ... In sixth- and fifth-century Greek art Athena is almost always shown wearing the aegis, which seems to be a combination breastplate and cloak ... often it has snake head for tassels ... and sometimes the Gorgon. ... Euripides in his Ion offers the strange idea that the aegis was the skin of the Gorgon.

p. 304

- As we saw in chapter 1, Homer mentions a Gorgon's head in both the Iliad and the Odyssey, but never Medusa by name, nor Perseus in connection with such an adventure. Indeed we cannot be entirely certain that Homer knew or thought of Gorgons as complete creatures suitable for decapitating. At one point we do find the Gorgon head on Athena's aegis (Il 5.738-42), but perhaps that detail is older than the explanation of how the head got there (or perhaps Homer knew rather Euripides' tale of Athena's slaying of a Gorgon at Phlegrai [Ion 989-96]). Our earliest sure reference to Perseus and the Gorgons is the Theogony, where Pursues cuts off Medusa's head (all three sisters are named here), and Chrysaor and Pegasus emerge from her neck (Th 270-81). ... In art the earliest representations appear to be the act of decapitation on two Boiotian relief pithoi (Louvre CA 795, CA 937),11 and the subsequent flight on the Protoattic Elesis amphora, all dating probably to the second quarter of the seventh century. On only one of the two relief pithoi is Medousa preserved (as a female Kentauros), but in both cases Perseus averts his gaze, thus attesting to the power of the Gorgon's face.

p. 305-307

p. 4128

- Apollodorus offers a more interesting story ... Herakles gives to Strop, daughter of Cepheus, a lock of Medousa's hair ...

p. 448

- One other reference ... when the Gigantes meet the gods at Phlegrai, Gaia brings forth as an ally for her sons a Gorgon (Ion 989-96). Athena slays the creature, and places its skin upon her breastplate, the aegis. Euripides does not say that the Gorgon was Medousa, and this alternative tale of the Gorgoneion on the Agis could conceivably be old, since Homer has nothing to contradict it; certainly it fits well with the Homeric notion of the Gorgon as a generic monster. On the other hand it seems suspicious that such a duel between goddess and Gorgon never appears in art, where it would have enlivened the usual iconography.

p. 450

Hard 2004

[edit]- It seems likely that the Gorgon's head or gorgoneion originated as an apotropaic image, existing independently as such before it was turned into a complete monster and thence into a trio of monsters.

- According to a strange story in Euripides' Ion, Athena acquired her gorgoeion by killing the Gorgon (here named) during the battle between the gods an Giants, after Gaia had brought the monster to birth to provide a fearsome ally for the Giants (who were sons of hers). Thus was probably a tale of fairly late origin, perhaps invented by Euripides himself; there is no sign of it anywhere else, whether in literary or artistic record.

Hopkins 1934

[edit]p. 341

- One remarks ... Curiously enough from the name Gorgo itself, our only other evidence period, we have the emphasis thrown on another feature, the voice, for it Sanscrit "garj" to shriek, and the Greek θόρυβος that the root is usually connected.

- It is no doubt the vagueness of these first references [in Homer] and the great difficulty of linking them all together into one satisfactory whole that has led to so many theories of the origin of the Gorgon. Ziegler in Pauly-Wissowa (VII, pp. 1645 ff.) gives an excellent summary of the hypotheses advanced before 1912: the various attempts to see the original Medusa in such natural phenomena as volcanic eruption, the ocean's roar, the sea waves, etc., the connection of the Medusa-head with [cont.]

p. 342

- The ghost-like character of the full moon, ...

p. 343

- Nor can we accept unreservedly the opinion that the Perseus-Gorgon story was already known in Mycenaean times because the Gorgon was known to Homer, ... In view of the later great popularity of the Perseus-Gorgon story it seems at least curious that Homer would not mention the incident if it were either current in his own day or a tradition handed down from Mycenaean times.

p. 344

- Furtwingler explained the early bearded Gorgon heads as a logical development from an originally male demon-mask. ...

- It seems perfectly clear from so many original variations allowing such wide differences in interpretation, ...

- It seems perfectly clear from so many original variations allowing such wide differences in interpretation, that there had been in the seventh century no commonly recognized form of the story in legend and art. To account for this fact there can, I believe, be only one explanation, a solution furnished by the evidence of Homer and the earliest the earliest representations in art. In the earliest period, the Mycenaean age, and geometric epoch, the head alone of the Gorgon monster was known both in story and in art. In the seventh century, therefore, when artists began to attempt the whole body they were free to fasten the head on any type of body they preferred, and they used this freedom with eagerness. Later on the Corinthian types were recognized as the best interpretations and these were universally adopted.

p. 345

- If our reasoning is correct, therefore, we may conclude that before the seventh century only the head of the Gorgon was known, that during the last half of that century the body was first represented and the story of the slaying of the Gorgon by Perseus first introduced. One suspects that some new influence, a force from outside, must have contributed to cause the sudden and immense popularity of the famous tale.

- It can be then, I believe, no mere coincidence that Assyrian art brings us a demon resembling the Greek Gorgon much more closely in many respects than does the Egyptian Bes, and Assyrian tradition a most striking parallel to the Perseus-Gorgon story. This is, of course, the figure of Humbaba and the story of his death at the hands of Gilgamesh.

Howe [= Feldman] 1954

[edit]p. 209

- Modern investigations into the Gorgon and gorgoneion have generally evolved around two kinds of rationalism, the zoological and the cosmological. Theorists of the first group, … concluded that the Gorgon concept originated in a fear of animals, …

- It was the psychologist Wilhelm Wundt who first recognized the universal aspects of the gotgoneion and its true meaning: a mask deriving from an admixture of animalistic features and of a type common to most primitive cultures. …

p. 210

- The most authoritative … [Roscher] based his conclusions on the Sanskrit stem of the name “Gorgon,” “garğ,” which has connotations of noise … Whereas the etymologists Boisacq and Meyer agree that "Gorgon" is derived from that stem, ... The Germanic and Romance languages also have numerous derivatives from this stem, and though all refer to the guttural, gurgling noises produced by it, ...itself10 Even the musical ramifications of the stem denotes a faking ... gargling ... the ode dedicated to a flute-player:11 ...

- 10 Greek offers ... "to gargle." But it is Latin and the modern languages which emphasize with striking consistency the mouth and throat and the noises produced by these, especially of the crude and unspoken kind: Latin offers: ... French: ... Italian: ... German: ...

p. 211

- When musical imagination refined that guttural sound implicit in the ancient and modern derivatives of “garğ,” it was produced not by plucking or beating, but with the breath blown into a narrow reed, a second throat attached to the real one.

- Admittedly … It is purely for this sonant reason that the Gorgon appears on monuments with a great distended mouth —to convey to the spectator the idea of a terrifying roar.

- ...

- Roscher's other evidence ... [cont.]

p. 212 but because ... which Roscher claims ...

- It is clear that some terrible noise was the originating force behind the Gorgon: a guttural, animal-like howl that issued with a great wind from the throat, and required a hugely distended mouth, while the tongue, powerless to give coherence, hung down to the jaw. So dominant was the idea of the noise and the face that, at first, no one gave thought to a body with normal arms and legs. But how did mask first arise and what was the meaning of its horrible outcry?

- In contriving this mask the Greek did what primitive peoples normally do in making such frightful masks: they gave expression to their fears, which in this case were specifically of beasts of prey. Thus the gorgoneion …

p. 213

- When used on such defensive armor [as the aegis of Athena and the shield of Agamemnon] the gorgoneion was plainly meant as apotropaism, a horror to avert horror.

- Such, … Yet it is possible that these early heads were intended as gorgoneia. Furtwangler suggests a logical explanation to the question of these borderline types, …

- Of the earliest incontestable gorgoneia …

p. 217

- Some scholars finding no solution in etymology,43 have attempted to see the Perseus-Gorgon [cont.]

p. 218

- Clark Hopkins, for example, saw a parallel to Perseus and the Gorgon in the Babylonian Gilgamesh and Humbaba. ...

Jameson

[edit]p. 22

- The story of Perseus was one of the most popular of Greek myths. It has long been recognized that in its Panhellenic form the story and its representations in art have clear Near Eastern connections.1

- 1 The Near Eastern connections have most recently been discussed by M. L. West, The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth, Oxford 1997; W. Burkert, The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age, Cambridge, MA 1992, esp. 85–7; on Perseus, “Oriental and Greek Mythology: The Meeting of Parallels,” in J. Bremmer, ed., Interpretations of Greek Mythology, London 1987, 10–40, esp. 26–9, and in “Die orientalisierende Epoche in der griechischen Religion und Literatur,” SitzHeid 1, 1984, 82–4. Particularly important is C. Hopkins, “Assyrian Elements in the Perseus-Gorgon story,” AJA 38, 1934, 341–58; more in H. Kantor, “A Bronze Plaque from Tell Tainat,” JNES 21, 1962, 93–117. See also R. D. Barnett, “Some Contacts between Greek and Oriental Religions,” in El ́ements orientaux dans la religion grecque ancienne, Strasbourg 1961, 143–53; B. Goldman, “The Asiatic Ancestry of the Greek Gorgon,” Berytus 14, 1961, 1–22; C. Hopkins, “The Sunny Side of the Gorgon,” Berytus 14, 1961, 25–35. The iconographic and mythological aspects are not always adequately distinguished. For the story type, see especially J. Fontenrose, Python: A Study of the Delphic Myth and its Origins, Berkeley 1959, 274–306, and, more generally, E. S. Hartland, The Legend of Perseus: A Study of Tradition in Story, Custom and Belief, vols. 1–3, London 1894–6.

p. 26

- The Greek Gorgons, unlike the possible Near Eastern models or parallels such as Humbaba and Lamashtu are always female. They have been seen as embodying the terrifying and dangerous side of female sexuality, a representation even of female sexual parts.11 This view, like the identification of the Gorgoneion as in origin a mask (discussed below), cannot be confirmed by textual or archaeological evidence. ...

p. 27

- A second important observation is that the Greek Gorgon was in origin a frightening mask, worn by a dancer. Since this was first propounded in the last century much more has been learned about early Greek masks, but there is still no early example of a mask in the form of a Gorgoneion of the type recognizable in art.13 The essential correctness of the interpretation is confirmed by rare but incontrovertible evidence for the use of frightening masks in early Archaic Greece, which show the general context, and by the widespread comparative evidence.14 The argument also draws support from the priority of the isolated head in poetry (Hom. Od. 11.633–5: Odysseus fears that Persephone may send a Gorgon’s head). In early art both isolated heads and embodied Gorgons are found, as is the case in Near Eastern examples of equivalent monsters. Neither type appears in Greek art before the seventh century BC, i.e., not before the full flood of Near Eastern artistic influence on Greece.15 Distinctive local forms of such [cont.]

p. 28

- masks were subsumed in a widespread Panhellenic representation devel-oped under Oriental influence. However, although there are Near Eastern sources for individual elements in the iconography, no precise model can be indicated. The familiar Gorgoneion was developed in Greece.

- As for the story of Perseus and the Gorgon, some elements, at least, were already in place before ca. 700 BC, to judge from Hesiod (Theog. 270–88). That Hesiod notes in only the most cursory fashion Medusa’s offspring by Poseidon, Chrysaor (Goldsword), and Pegasus, at the moment of her beheading, shows that these figures were well established before Hesiod composed his poem. (Homeric silence at Od. 11.633–5 strikes me as neutral – it cannot be used to show that Perseus’ adventures were known or unknown.) Whatever the origin of the Gorgons of the Perseus story, both they and the hero seem to have had a place in the Greek imagination before the seventh century BC, and thus before their appearance in art.

Karoglou

[edit]- Beginning in the fifth century B.C., the Gorgon Medusa - a legendary monster whose gaze could turn beholders to stone-underwent a visual transformation from grotesque to beautiful, becoming in the process increasingly anthropomorphic and feminine. A similar shift ni the representations of other mythical female half-human beings (or hybrids), such as sphinxes, sirens, and the sea monster Scylla, took place at the same time.1 The iconographic makeover of these inherently terrifying figures-symbols fo death and the Underworld believed to have apotropaic (protective) powers-was a result of the idealizing humanism of Greek art of the Classical period (480-323 вc.). Hybrids continued to evolve in form and meaning after the Classical period, however, and many still resonate in modern culture and the artistic imagination.2

- In Classical Greek art, Medusa was progressively transformed into an attractive young woman. Simultaneously an aggressor and a victim, she became a tragic figure, as evidenced by Attic representations of her death. A red-figure pelike attributed to the painter ...

Krauskopf and Dahlinger

[edit]p. 288

- Das Gorgoneion ist das bei weitem am häufigsten dargestellte antike Dämonenbild.

- The Gorgoneion is by far the most frequently depicted ancient demon image.

I. Gorgoneia: 1-228

- A. Isolated Gorgoneia: 1-145

- a) Preliminary stages and the development of fixed types (ca. 700-620 BC): 1-15

- b) Archaic types and the transition to the middle type: 16-79

- c) The middle type of the 5th and 4th centuries: 80-106

- d) The beautiful type and Hellenistic mixed forms : 107-145

- 1. Without wings, with snakes: 107-121

- 2. Without wings and without snakes: 122-126

- 3. Winged: 127-145

- Front view: 127-133

- Head in three-quarter view: 134-143

- In profile: 144-145

- B. Gorgoneion as the center of animal vertebrae: 146-151

- C. Gorgoneion in the center of the triskelion: 152-153

- D. Gorgoneion flanked by sphinxes: 154-155

- E. Gorgoneia on shields: 156-193

- a) Shields and shield symbols: 156-158

- b) Representations of shields: 159-193

- 1. The first attempts: 159-162

- 2. Archaic types and transitional forms to the middle type : 163-174

- 3. Middle type: 175-181

- 4. Beautiful type: 182-189

- Without wings: 182-187

- Winged: 188-189

- 5. Agis with Gorgoneion on shields: 189a-193

- Beautiful type with wings: 189a-192

- Archaic type: 193

- F. Aegis-Gorgoneia and Gorgoneia on depictions of armor: 194-228

- a) Archaic and transitional types 194-201

- b) The middle type: 202-213

- c) Beautiful type: 214-228

- 1. Agis carried by Athena: 214-216

- 2. Isolated Âgis: 217-228

- 3. Middle type: 175-181

- 4. Beautiful type: 182-189

- Without wings: 182-187

- Winged: 188-189

- 5. Agis with Gorgoneion on shields: 189a-193

- Beautiful type with wings: 189a-192

- Archaic type: 193

II. Gorgons without any plot connection: 229-288

- A. Isolated Gorgons: 229-266

- a) Early types: 229-231

- b) Archaic Gorgons in knee-running pattern: 232-259

- c) Late Archaic running Gorgons in long chiton: 260-261

- d) Sitting and kneeling Gorgons: 262-264

- e) Half-figures: 265-266

- B Gorgons in animal friezes: 267-270

- C Medusa with Pegasus: 271-278

- D. Gorgon as Potnia Theron: 279-282

- a) Holding animals with both arms: 279-282

- b) Two Gorgons with an animal: 283

- c) Fighting with animals (?): 284-286

- d) Flanked by animals: 287-288

III. The Corfu Pediment: 289

IV. The Beheading of Medusa: 290-311

- A. Without Pegasus and Chrysaor: 290-306

- B. With Pegasus and/or Chrysaor : 307-311. . . -

V. The Pursuit of Perseus: 312-334

- A. With the collapsing Medusa, without Pegasus and Chrysaor: 312-318

- B. With Pegasus and Chrysaor: 319-327

- C. Without Medusa 328-334

VI. Perseus with the Head of Medusa: 335-342.

VII. Gorgon as Ferryman of the Dead: 343

VII. Gorgoneion on bodies other than women: 344-351

- A. Connected to horse body: 345-346

- B. With sphinx body: 345-346

- C. Other hybrid creatures: 347-351

- 156 Bronze shield. London, BM. From Carchemish. - Kunze, E., OlympBer 5, 1956, 48-50 fig. 26; Beazley, a. O. 146, 60; Floren 62 no. g pl. 5, 2. - Late 7th century BC - G. (straight, open mouth with teeth and tusks) surrounded by a wreath of snakes, as the central motif of an animal frieze shield.

- 157 Bronze shield. Samos, Vathy, Mus. B 933. From the Heraion. - Walter-Karydi, a. O. 39, 36 pl. 59; Karagiorga 2, 154 No. VI 25; Floren 62 No. k pl. 5,5 2.- 2nd quarter of the 6th century BC - tusks, nasal folds, chin protrusion. Snake wreath, snakes larger in the lower part. Niche votive shield Samos B 1286.1961 (Floren 62 h)

- 158a Golden shield below the Nike in the central acroter of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, consecrated by the Spartans and their allies after the Battle of Tanagra (457 BC). Not preserved. Paus. 5, 10, 4 ("Μέδουσαν τὴν Γοργόνα" probably means a Gorgoneion rather than a running Gorgon), for the inscription see Olympia V 370-374 No. 253

- 292. Bronze shield band. Olympia, Mus. B 975. From Olympia. — Kunze, Schildbänder 136-138 Form XXIXS Pl. 57; Karagiorga 151 No. 17; Schefold, SB 11 82 Fig. 94; Stucchi 35 Fig. 9c. - Shortly before the middle of the 6th century BC - Medusa in the Corinthian type (two wings, four snakes on the head).

Mack 2002

[edit]p. 572

- It has long been the consensus among classical scholars that the gorgoneion be identified as an apotropaion, a device that was deployed by ancient Greeks to turn away (apotrepein) unwanted or threatening forces.3

p. 573

- This is a compelling account, and it constitutes our clearest and most direct evidence for an identification of the gorgoneion as an apotropaion. It articulates the affective capacity of the image as a manifest force capable of `turning away' those who engage it; and it does so in terms that are precise and specific, leaving no doubt as to the difference between the gorgoneion and the other [cont.] representations that decorate Agamemnon's shield.

p. 599, n. 3

- The classic statement is by Jane Harrison in Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion (1903), Princeton 1991, pp. 187-91. Her account of the gorgoneion as part of 'the apparatus of a religion of terror' (and, in particular, as a 'ritual mask misunderstood') remains the basis for most current thinking about the image (see for example, J.D. Belson, 'The Gorgoneion in Greek Architecture', PhD Dissertation, Bryn Mawr College, 1981; J.L. Benson, 'The Central Group of the Corfu Pediment', Antike Kunst, vol. 4, 1987, pp. 48±60; J.B. Carter, 'The Masks of Orthia', American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 91, 1987, pp. 355-83; C. Faraone, Talismans and Trojan Horses: Guardian Statues in Ancient Greek Myth and Ritual, Oxford, 1992, p. 38)....

p. 599 n. 5

- The monstrosity of the frontal face, as Vernant has shown (op. cit. [note 1]), articulates the power of the gaze through a rich web of associations. Features like the grimace, the bared teeth, the apparent shriek, the long and unruly hair, and, of course, the glaring eyes themselves, participate in networks of metaphors for murderous fury (menos), various kinds of possession, female sexuality, the wild or untamed, and death. Alongside the startling collapse of categories in the face (natural and supernatural, human and animal, male and female), these various associations position the gorgoneion as an image of what Vernant calls 'extreme alterity' (ibid., p. 111). It is worth noting that sound, though only indirectly a feature of the face, was central to the conceptualization of Medusa's terrifying power: the name 'Gorgon' derives from the Sanskrit stem garğ, meaning to roar or shriek; accounts of the monster describe her baleful dirge (oulios threnos) and piercing groan (eriklagton goon) (Pind., Pyth 12.6-8, 21), as well as the hiss (iachema) and furiously clattering teeth (menei d'echarasson odontas) of her snakes (Eurip. Her. fur. 881-2; Hesiod Aspis 231-5, where it is an image of snake-girdled, running gorgons that is made auditory); and her cry is the source for Athena's invention of flute-music (see Vernant, op. cit. [note 1], pp. 117-18, 123-7, with additional references; Frontisi-Ducroux, Du masque au visage, op. cit. [note 3], pp. 74-5).

p. 602 n. 30

- That the figure of Medusa was embedded within the Perseus legend seems surely to have been the case throughout the archaic and classical periods, when both image and myth were in wide circulation. While questions of origin are of less interest to me here, it is my own sense that we have no reason not to believe that this had always been the case (particularly if both the figure of Medusa and the Perseus legend have a common derivation in earlier `Eastern' prototypes, such as Humbaba and the epic of Gilgamesh). The counter argument is made, of course, by Harrison: `the ritual object comes first; then the monster is begotten to account for it; then the hero is supplied to account for the slaying of the monster.' (op. cit. [note 3], p. 187) It is worth pointing out that, strictly speaking, we have no evidence for an anterior use of the face of Medusa as a ritual mask (the one possible exception being three terracotta `masks' from Tiryns, which share some features with the iconography of the gorgoneion; see LIMC, vol. 4, s.v. Gorgo, Gorgones, no. 2) (cf. Vernant, op. cit. [note 1], p. 130)

Napier 1986

[edit]p. 46

- Terra-cotta votive masks from the Temple of Artemis Ortheia, Sparta. 7th-6th c. B.C. These artifacts are significant in the categorizing of preclassical masks, and important for comparative purposes, as they have frequently been associated with facial types found as far away as Carthage and Babylonia. Portrayed are either man molds or votive copies of actual masks.

p. 46 Pls. 9a-10b

p. 47 Pls. 11a-12b

pp. 83 ff.

p. 85

- ... Artistic evidence points to the legend's [Perseus-Gorgon story] presence in the middle of the seventh century BC; and if we take horrific Gorgon-like faces, such as those from Tiryns (Pl. 34), as evidence, we might push the date back to the eighth century.3

p. 86 Pl. 34

- Gorgonesque helmets from Tiryns. Late 8th or early 7th c. B.C. These masks represent what are probably the earliest known examples of the Gorgon type. They have been compared to the grotesque masks or mask molds of Artemis Orthia (Pls. 9-12) and were, like them probably connected to a masked performance in honor of a Gorgon-masked goddess. Athens, Deutsches Archäolgisches Institut, neg. nos 1051, 1388, 1369.

Napier 1992

[edit]p. 102

- The Greek Gorgo has frequently been connected to the Sanskrit garj, "to (emit a) growl, roar." Gorgō also has as cognates such words as "gorge," "gorgeous," and "Gargantua." Its sound value in itself is also worth considering. Gargaphia, for instance, is the name of a sacred spring near Mount Kithairon (Burkert [1972] 1983, 113). The root *gharga, R. L. Turner tells us in A Comparative Dictionary of Indo-Aryan Languages (1969), refers to the "gurgling sound of water," while gárgara is a whirlpool itself.

Ogden 2008

[edit]p. 34

- ... The Iliad gives us a gorgoneion (a full-face Gorgon image ) on the shield of Agamemnon: ... again apparently an image, on the aegis worn by Athena ... The poem further implies that the Gorgon's eyes were already particularly terrible, in describing Hector's eyes akin to those of a Gorgon (8.348-9).

p. 35

- The two earliest extant images of Perseus decapitating a Medusa and fleeing from her sisters ca. 675-50 BC. In these images the faces of Medusa and the Gorgons are shown frontally, which in itself strongly identifies them with gorgoneia. In the first, on a Boeotian pithos, we find Perseus, ... [cont.]

p. 36

- ... decapitating Medusa in the form of a female centaur, ... (LIMC Perseus no. 117 = Fig 3.1). The fact that Perseus is turning away as he does tells us that it is already established that to look at her face brings death.

p. 37

- If gorgoneia had an origin separate from he Medusa story, then any meaning or mythical context they may have had prior to it is irrecoverable. But we can in any case something on their function, and function may in fact been everything. It is clear from the Iliad gorgoneion-shield that gives rise to a miasma of Terror or Fear that gorgoneia served as apotropaic shield devices, devices to inflict terror on the enemy.

p. 38

- The second complicating issue is whether gorgoneia or the Medusa tale were influence by Mesopotamian and other Near-Easter material. Various 'Mistress of Animals', Lamashtu and Humbaba, present cases to answer, at least at the level of iconography. On the famous pediment of the temple of Artemis in Corfu of ca. 590 BC (LIMC Gorgo no. 289) ...... kneeling-running configuration ...

p. 39

p. 40

Ogden 2013

[edit]p. 93

- Gorgoneia, the representations of the Gorgon's disembodied, full-frontal, viewer-challenging, face that flourished throughout ancient art (not least on shields, acroteria, and ante fixes) and had a wide range of apotropaic functions, often feel semi-independent of the Perseus-Medusa narrative that supposedly explained their origin, and indeed they may have had separate roots, but even so both seem to have come into existence at roughly the same time. Gorgoneia are first attested in the artistic record from c.675 BC, and soon evolve into a canonical 'lion mask type'. They typically have bulging, staring eyes. Their mouths form rictus grins with fangs and tusks projecting up and down, and a lolling tongue protrudes from them. Their hair forms serpentine curls, with actual snakes becoming apparent by the end of the seventh century.122

- The Perseus-Medusa story is first found in the iconographic record two pots dated to c.675-650 BC. On the first, a Boeotian pithos, Perseus equipped with kibisis and sword decapitates a Medusa in the form of a female centaur, whilst looking away from her (no snakes are in evidence). On the second, a Proto-Attic amphora, Perseus flees two striding, wasp-bodidied, cauldron-headed Gorgon sisters, leaving behind the rotund, decapitated corpse of Medusa, whilst Athena interposes herself to protect him from his pursuers. In these images the faces of Medusa and the Gorgons are shown frontally, which in itself strongly identifies them with gorgoneia, and in the second snakes project from their heads and neck.123

p. 94

- Whether the Perseus-Medusa tale originated in a desire to give an etiology for gorgoneia or not, it is possible that the story as developed was indirectly inspired by Near-Eastern Iconography. In a Perseus scene-type first attested from c.550 BC (though possibly older), we find a front-facing round headed, grinning-grimacing Medusa, her legs in the kneeling-running configuration, flanked by Perseus and Athene, with Perseus decapitating her as he turns his [cont.]

p. 95

- head away.125 The configuration appears to be derivative of Mesopotamian depictions of a very different tale of Gilgamesh and Enkidu slaying the wild man Humbaba. In these the hero can turn away to look for a helping goddess to hand him a weapon. The similarity suggests that the core of the Medusa myth, consisting of her petrifying gaze and her slaughter, originated precisely in a radical reinterpretation of what is happening in the Mesopotamian vignette.126 The notion that Medusa gave birth to Pegasus and Chrysaor upon her decapitation may derive in part from reinterpretations of Mesopotamian images of the child-devouring demoness Lamashtu who, as we have seen, was otherwise brought into Greek culture in her own right as Lamia. The serpent-waisted and -necked Medusa of the famous pediment of the temple of Artemis in Corfu of c.590 BC, who is flanked in 'Mistress of Animals' fashion by a rampant Pegasus and an upreaching Chrysaor, and then by lions, exhibits strong affinities in content and composition with Lamashtu images. Lamashtu is often portrayed as lion headed, clutching a snake in each hand (as we noted above), with a rampant animal on either side, again in the so-called 'Mistress-of Animals' configuration; she rides on as ass (whose function is to carry her away to where she can do no harm). One particular image of her from Carchemish strikingly resembles the Corfu pediment in its overall arrangement.127

- 125LIMC Perseus nos. 113, 120-2.

p. 96

- A new development commences with the age of Pindar, at the beginning of the fifth century BC: Medusa's snakes are more consistently identified with her hair, whilst her face becomes no longer that of the leering gorgpneion, but that of a beautiful young woman.131

Phinney 1971

[edit]p. 446

- The provenance of the Gorgons and Perseus, who beheaded Medusa, is still an open question among scholars.

p. 447

- Even the noisiness of the Gorgon that is implied in her name (cf. Sanskrit garğ 'howl' and Greek γαργαρίς 'noise')

Potts

[edit]Tripp

[edit]s.v. Gorgons

- Three Snaky-haired monsters, named Steno, Euryale, and Medusa. Euripides says that Ge brought forth "the Gorgon" to aid her children, the Giants, in their war with the gods. Others claim that the Gorgons were among the brood that sprang from the union of the ancient sea-god Phorcys and his sea-monster sister, Ceto; these offspring included Echidna, Ladin, and the Graeae. The Gorgons had brazen hands and wings of gold; red tongues lolled from their mouths between tusks like those of swine; and serpents writhed about their heads. Their faces were so hideous that a glimpse of them would turn man or beast to stone. Of the three, only Medusa was mortal. She was killed by Perseus. [Hesiod, Theogony, 270-283. See also references un der PERSEUS.]

s.v. Medusa

- One of the three snakes haired monsters known as the GORGONS. Medusa, unlike her sisters, Stheno and Euryale, was immortal . In late versions of the myth she was said to have been a beautiful maiden. Pursued by many suitors, she would have none of them, until Poseidon lay with her in a flowery field. She incurred the enmity of Athena, either because the goddess envied her beauty or because Medusa had yielded to Poseidon in Athena's shrine. In any case, the goddess turned Medusa lovely hair into serpents and ... From Medusa's neck sprang the warrior Chrysaor and the winged horse Pegasus, her children by Poseidon.

Vernant 1991 (1985)

[edit]"Chapter 6: Death in the Eyes: Gorgo, Figure of the Other" in Vernant, Jean-Pierre, Mortals and Immortals: Collected Essays, Froma I. Zeitlin (editor), Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1991.[Originaly published as La mort dans les yeux - Figures de l'autre en Grèce ancienne, Artémis, Gorgô Paris, 1985.]

p. 111

- Such [the extreme otherness of the non-human] we think, were the sense and function of this strange Power that operates through the mask, that has no other form than the mask, and that is presented entirely as a mask: Gorgo.

- In certain qualities she is close to Artemis.1 In the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia in Sparta, among the votive masks dedicated to the goddess (the young had to ware likenesses of these in the course of the agōgē in order to execute their mimetic dances), there are many that reproduce the monstrous and terrifying face of Gorgo.

- 1 Both have affinities with Potnia therōn, the great feminine divinity, mistress of the wild beasts and of wild nature, who proceeded them in the Creto-Mycenaean world and whose legacy each inherits in her own way by profoundly transforming it in the context of civic religion.

p. 112

- Plastic representations of Gorgo—both the gorgoneion (the mask alone) and the full feminine figure with a gorgon face—appear not only on a series of vases, but from the archaic period on, they can be seen on façades of temples or as acroteria and antefixes. We find them on emblems on shields or decorating household utensils, hanging in artisan's' workshops, attached to kilns, set up in private residences, and also, finally, stamped on coins. This representation first appears early in the seventh century B.C.E., and by the end of the second quarter of the same century, the canonical types of the model are already codified in there essential features. Leaving aside the variants in Corinthian, Attic, and Laconian imagery, we can, on a first analysis, identify two characteristic in the portrayal of Gorgo.

- First, frontality. In contrast to the figurative conventions determining Greek pictorial space in the archaic period, the Gorgon is always, without exception, represented in full face. Whether mask or full figure, the Gorgon's face is at all times turned frontally toward the spectator who gazes back at her.

p. 115

- The affinities between Gorgo and the Mistress of Animals, the Potnia, as Theodora Karagiora strongly emphasizes,13 are more promising. ...

p. 117