User:Memelord0/sandbox

The hypothesis today is primarily adopted by Afrocentrists.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8] while Asante maintains that Diop predates the term.[9] Advocates of the hypothesis believe race is commonly used by historians,[10]: 50–52 the black racial category was comprehensive enough to absorb the various phenotypes in Ancient Egypt, and "many of the most powerful Egyptian dynasties...one can usefully call black."[11]: 48, 55 [12]: 242 The hypothesis includes a particular focus on identifying links to Sub-Saharan cultures and the questioning of the race of specific notable individuals from Dynastic times, including Tutankhamun,[13] the king represented in the Great Sphinx of Giza,[14][15] and Greek Ptolemaic queen Cleopatra.[16][17][18][19][20][21]

Mainstream scholars reject the notion that Egypt was a black (or white) civilization; they maintain that, despite the phenotypic diversity of Ancient and present-day Egyptians, applying modern notions of black or white races to ancient Egypt is anachronistic.[22][23][24] They reject the notion that Ancient Egypt was racially homogeneous; instead, skin color varied between the peoples of Lower Egypt, Upper Egypt, and Nubia, who in various eras rose to power in Ancient Egypt. At the UNESCO "Symposium on the Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic script" in Cairo in 1974, the Black hypothesis was met with profound disagreement.[25] Nearly all participants concluded that the ancient Egyptian population was indigenous to the Nile Valley, and was made up of people from north and south of the Sahara who were differentiated by their color.[26] Moreover, "Most scholars believe that Egyptians in antiquity looked pretty much as they look today, with a gradation of darker shades toward the Sudan".[27]

History

[edit]Some modern scholars such as W. E. B. Du Bois,[28] Chancellor Williams,[29] Cheikh Anta Diop,[11][30][10]: 1–61 John G. Jackson,[31] Ivan van Sertima,[32] Martin Bernal,[33] Anténor Firmin and Segun Magbagbeola[34] have supported the theory that the Ancient Egyptian society was mostly Black.[10]: 31–32, 46, 52 The frequently criticized Journal of African Civilizations[35] has continually advocated that Egypt should be viewed as a Black civilization.[36][37] The debate was popularized throughout the 20th century by the aforementioned scholars, with many of them using the terms "Black", "African", and "Egyptian" interchangeably,[38] despite what Frank Snowden calls "copious ancient evidence to the contrary".[39][40]

At the UNESCO "Symposium on the Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic script" in Cairo in 1974, the Black Egyptian hypothesis met with profound disagreement.[25] Similarly, none of the participants voiced support for an earlier theory where Egyptians were "white with a dark, even black, pigmentation."[10]: 43 The two proponents of the Black Egyptian Hypothesis (Diop and Obenga) presented what G. Mokhtar referred to as "extensive" and "painstakingly researched" evidence[41][30][10]: 37, 55 to support their views, which contrasted sharply with prevailing views on Ancient Egyptian society. Nearly all participants concluded that the ancient Egyptian population was indigenous to the Nile Valley, and was made up of people from north and south of the Sahara who were differentiated by their color.[26] Diop and others believed the prevailing views were fueled by scientific racism and based on poor scholarship.[11]: 1–9, 24–84

Position of modern scholarship

[edit]Since the second half of the 20th century, most scholars have held that applying modern notions of race to ancient Egypt is anachronistic.[22][23][24] The focus of some experts who study population biology has been to consider whether or not the Ancient Egyptians were primarily biologically North African rather than to which race they belonged.[42] In the non-racial bio-evolutionary approach, the Nile Valley population is part of a continuum of population gradation or variation among humans that is based on indigenous development, rather than using racial clusters or the concept of admixtures.[43] Under this approach, racial categories such as "Blacks" or "Caucasoids" are discarded in favor of localized populations showing a range of physical variation.

Stuart Tyson Smith writes in the 2001 Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt that "Any characterization of race of the ancient Egyptians depends on modern cultural definitions, not on scientific study. Thus, by modern American standards it is reasonable to characterize the Egyptians as 'black', while acknowledging the scientific evidence for the physical diversity of Africans."[44] Scholars, such as Bruce Trigger, condemned the often shaky scholarship on the Egyptians. He declared that the peoples of the region were all Africans, and decried the "bizarre and dangerous myths" of previously biased scholarship, "marred by a confusion of race, language, and culture and by an accompanying racism."[45]

In 2008, S. O. Y. Keita wrote that "There is no scientific reason to believe that the primary ancestors of the Egyptian population emerged and evolved outside of northeast Africa.... The basic overall genetic profile of the modern population is consistent with the diversity of ancient populations that would have been indigenous to northeastern Africa and subject to the range of evolutionary influences over time, although researchers vary in the details of their explanations of those influences."[46] Frank J. Yurco, an Egyptologist at the Field Museum and the University of Chicago, said: "When you talk about Egypt, it's just not right to talk about black or white, That's all just American terminology and it serves American purposes. I can understand and sympathize with the desires of Afro-Americans to affiliate themselves with Egypt. But it isn't that simple [..] To take the terminology here {in the United States} and graft it onto Africa is anthropologically inaccurate". Yurco added that "We are applying a racial divisiveness to Egypt that they would never have accepted, They would have considered this argument absurd, and that is something we could really learn from."[47] Yurco writes that "the peoples of Egypt, the Sudan, and much of North-East Africa are generally regarded as a Nilotic continuity, with widely ranging physical features (complexions light to dark, various hair and craniofacial types)".[48]

According to Bernard R. Ortiz De Montellano, "the claim that all Egyptians, or even all the pharaohs, were black, is not valid. Most scholars believe that Egyptians in antiquity looked pretty much as they look today, with a gradation of darker shades toward the Sudan".[27] In his We Can't Go Home Again: An Argument About Afrocentrism, historian Clarence E. Walker writes that Black Americans who claim Egypt was a black civilization and the progenitor of Western civilization have created a "therapeutic mythology", but they aren't talking about history.[49] Kathryn Bard, Professor of Archaeology and Classical Studies, wrote in Ancient Egyptians and the issue of race that "Egyptians were the indigenous farmers of the lower Nile valley, neither black nor white as races are conceived of today".[50] Barbara Mertz writes in Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt: "Egyptian civilization was not Mediterranean or African, Semitic or Hamitic, black or white, but all of them. It was, in short, Egyptian."[51]

Kemp argues that the black/white argument, though politically understandable, is an oversimplification that hinders an appropriate evaluation of the scientific data on the ancient Egyptians since it does not take into consideration the difficulty in ascertaining complexion from skeletal remains. It also ignores the fact that Africa is inhabited by many other populations besides Bantu-related ("Negroid") groups. He asserts that in reconstructions of life in ancient Egypt, modern Egyptians would therefore be the most logical and closest approximation to the ancient Egyptians.[52] Professor Stephen Quirke, an Egyptologist at University College London, expressed caution about the researchers’ broader claims, saying that “There has been this very strong attempt throughout the history of Egyptology to disassociate ancient Egyptians from the modern population.” He added that he was “particularly suspicious of any statement that may have the unintended consequences of asserting – yet again from a northern European or North American perspective – that there’s a discontinuity there [between ancient and modern Egyptians]".[53]

National Geographic reported in their reference populations for their genographical DNA study showed that 68% of modern-day Egyptians are ethnically North African, with foreign invasions having little effect on the majority of modern Egyptians's genetics.[54] Other ethnic groups that rounded out modern Egyptians were from Southwest Asia and the Persian Gulf at 17%, Jewish diaspora at 4%, Asia Minor at 3%, Eastern Africa at 3%, and Southern Europe at 3%.[54]

Greek and Roman historians

[edit]The Black African model relied heavily on the interpretation of the writings of Classical historians.[11]: 1–5, 241–242, 278, 288 [55] Some of the most often quoted historians are Herodotus, Strabo, and Diodorus Siculus.[10]: 15–60 [56]: 242, 542 According to advocates, Herodotus states the Egyptians were "black skinned with woolly hair",[11]: 1 (about Oracles) "by calling the bird black, they indicated that the woman was Egyptian",[11]: 1 and "the Colchians, the Egyptians, and the Ethiopians are the only races which from ancient times have practiced circumcision".[57][11]: 1–5, 241–245, 288 Lucian observes an Egyptian boy and notices that he is not merely black, but has thick lips.[10]: 21, 38 Diodorus Siculus mentioned that "the majority of Nile dwelling Ethiopians were black, flat nosed.." and Ethiopians were "originators of many customs practiced in Egypt, for the Egyptians were colonists of the Ethiopians."[58][11]: 1-2}, 56–57 Apollodorus calls Egypt the country of the black footed ones.[10]: 15–60 Aeschylus, a Greek poet, wrote that Egyptian seamen had "black limbs."[10]: 26

Critics of the hypothesis have noted that Flavius Philostratus said the inhabitants of the area near the Nubian boundary were "not as black as Ethiopians but darker than Egyptians".[59] Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus used the adjective "subfusculi" (somewhat dark) to describe Egyptians in contrast to the pure Ethiopians around Meroe.[60] Roman poet Marcus Manilius classified dark and black skinned peoples as follows: "Ethiopians, the blackest; Indians, less sunburned; Egyptians, mildly dark; and Moors, the lightest".[59] Greek historian Arrian emphasized the differences between Ethiopians, Egyptians and Indians: "southern Indians resemble Ethiopians in that they are black, but not so flat-nosed or woolly-haired; whereas northern Indians are physically more like Egyptians".[60]

Herodotus has been called both the "father of history"[61] and "the father of lies".[62][63] Writing between the 450s and 420s BC, Herodotus lived at a time when Egypt was a colony of Persia, and had previously experienced nine decades under the rule of the Kushite 25th Dynasty. There is dispute about the historical accuracy of the works of Herodotus – some scholars support the reliability of Herodotus[11]: 2–5 [64]: 1 [65][66][67] while other scholars regard his works as being unreliable as historical sources, particularly those relating to Ancient Egypt.[68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79]

Melanchroes translation controversy

[edit]There is considerable controversy over the English translation of the Greek word melanchroes.[11]: 242, 278, 288 [80][81] Many advocates translate it as black.[11]: 1, 27, 43, 51, 242, 278, 288 [10]: 21, 26, 45 [82][83][84][56][85][86] Simson Najovits, a critic, states that "dark-skinned" is the usual translation of the original Greek Melanchroes.[87] In responding to Mauny's criticism of Diop's use of the word black (as opposed to brown skin), Diop said "Herodotus applied melanchroes to both Ethiopians and Egyptians...and melanchroes is the strongest term in Greek to denote blackness."[11]: 1–5, 241–242, 278, 288 Snowden mentions that Greeks and Romans knew of "negroes of a red, copper-colored complexion are known among African tribes",[88] and proponents of the Black theory believed that the Black racial grouping was comprehensive enough to absorb the red and black skinned images in ancient Egyptian iconography.[88] The British Africanist Basil Davidson stated "Whether the Ancient Egyptians were as black or as brown in skin color as other Africans may remain an issue of emotive dispute; probably, they were both. Their own artistic conventions painted them as pink, but pictures on their tombs show they often married queens shown as entirely black,[89] being from the south : while the Greek writers reported that they were much like all the other Africans whom the Greeks knew."[90]

Supporters of the "dark skinned" translation presented evidence to support their position. Alan B Lloyd wrote that "there is no linguistic justification for relating this description to negroes. Melanchroes could denote any colour from bronzed to black and negroes are not the only physical type to show curly hair.[91] These characteristics would certainly be found in many Egs [Egyptians], ancient and modern, but they are at variance with what we should expect amongst the inhabitants of the Caucasus area.[92] According to Frank M.Snowden, "Both Bernal and other Afrocentrists are mistaken in assuming that the term Afri (Africans) and various color adjectives for dark pigmentation as used by Greeks and Romans are always the classical equivalents of Negroes or Blacks in modern usage"[93] Snowden claims that Diop "not only distorts his classical sources but also omits reference to Greek and Latin authors who specifically call attention to the physical differences between Egyptians and Ethiopians".[94] Simson Najovits states that Herodotus "made clear ethnic and national distinctions between Aigyptios (Egyptians) and the peoples whom the Greeks referred to as Aithiops (Ethiopians)."[95]

Racial and biological affinites

[edit]Diop always maintained that Somalians, Nubians, Ethiopians and Egyptians were all part of a related range of African peoples in the Nilotic zone that also included peoples of the Sudan and parts of the Sahara. He said that their cultural, genetic and material links could not be defined away or separated into a regrouped set of racial clusters.[96] According to Diop, "as far as the dark red race is concerned, we shall see that it is simply a subgroup of the black race as presented on the monuments...In reality, there is no dark red race; only three well defined races exist: the white, the black, and the yellow."[11]: 43 At UNESCO, Obenga said "race was recognized as valid by scientific research."[10]: 50–51 Diop and Obenga agreed that there were two black races "one with smooth hair and one with crinkly hair.[10]: 50–51 At UNESCO, Professor Vercoutter said "more specific criteria were essential...to provide a scientific definition of the black race...he mentioned blood criterion..and whether, for example, the Nubians should be considered negroes.[10]: 50–51 Stuart Tyson Smith writes in the Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt that "Any characterization of race of the ancient Egyptians depends on modern cultural definitions, not on scientific study. Thus, by modern American standards it is reasonable to characterize the Egyptians as 'black', while acknowledging the scientific evidence for the physical diversity of Africans."[44] On the other hand, Professor Sauneron said roughly 2000 Ancient Egyptian bodies have been studied (by 1974), which was not enough to draw ambitious racial conclusions for an area that has supported several hundred million people since the beginning of historical times.[10]: 52 Since the second half of the 20th century, most scholars have held that applying modern notions of race to ancient Egypt is anachronistic.[22][23][24] Scholars such as Kemp, Yurco, Barbara Mertz and Kathryn Bard believe ancient Egyptians shouldn't be classified as black or white as races are conceived of today.[51][97][52][47]

African American physical anthropologist S.O.Y Keita argued that "the real issue is not the Egyptians' race", which Stephen Howe believes is an "inherently undecidable question, based on historically varying ideological concepts", Keita believes the question is "population affinity" (to whom were the Egyptians most closely related). His conclusion was that "The Egyptians of the earlier periods, especially in the south, were physically a part of what can be called the Saharo-tropical variant range and retained this major affinity even when diversifying. The base population of Egypt included the descendants of earlier populations, and some Levantines and Saharan immigrants".[98] On the other hand, a physical anthropology research team headed by C. Loring insist that the whole language of race is an obfuscation, and believe "the claims made by Diop, Bernal and others are "hopelessly simplistic, misleading and basically wrong". According to Brace & co, "the ancient Egyptian population had very few affinites with that of subsaharan Africa, while ties with other parts of North Africa, the European Neolithic and more distantly India were more evident". Keita, though more sympathetic to Afrocentric ideas according to Howe, is "in broad agreement". His analysis indicates diversity, with a range of skull types intermediate between those in Europe and those in Subsaharan Africa, with remains from Upper Egypt showing more 'African' features than their northern counterparts.[98]

Melanin samples

[edit]While at the University of Dakar, Diop used microscopic laboratory analysis to measure the melanin content of skin samples from several Egyptian mummies (from the Mariette excavations). The melanin levels found in the dermis and epidermis of that small sample led Diop to classify all the ancient Egyptians as "unquestionably among the Black races".[11]: 236–243 At the UNESCO conference, Diop invited other scholars to examine the skin samples.[10]: 20, 37 [99] Diop also asserted that Egyptians shared the "B" blood type with black Africans.

The other scholars at the symposium however rejected Diop's Black-Egyptian theory.[100]

Language

[edit]Diop and Théophile Obenga attempted to linguistically link Egypt and Africa, by arguing that the Ancient Egyptian language was related to Diop's native Wolof (Senegal).[101] Diop's work was well received by the political establishment in the post-colonial formative phase of the state of Senegal, and by the Pan-Africanist Négritude movement, but was rejected by mainstream scholarship. In drafting that section of the report of the UNESCO Symposium, Diop claimed linguistic analyses "revealed a large measure of agreement among the participants" and Diop and Obenga's reports "were regarded as being very constructive".[10]: 31, 54 However, in the discussion thereof in the work Ancient Civilizations of Africa, Volume 2, the editor has inserted a footnote stating that these are merely Diop's opinions and that they were not accepted by all the experts participating.[102] In particular, Prof Abdelgadir M. Abdalla stated that "The linguistic examples given by Prof Diop were neither convincing nor conclusive."[103]

Influence of foreign invasions

[edit]According to Hisham Aidi, "The notion of Arabs as invaders who drove North Africa’s “indigenous” inhabitants below the Sahara is repeated ad absurdum by influential African and Afro-diasporan scholars, despite evidence to the contrary ... most scholars concur that North Africans have always been multi-hued, and there is no evidence of a black North Africa obliterated by invaders".[104] James Newman writes in his The Peopling of Africa: A Geographic Interpretation: “It was not that Arabs physically displaced Egyptians. Instead, the Egyptians were transformed by relatively small numbers of immigrants bringing in new ideas, which, when disseminated, created a wider ethnic identity".[105] According to Bernard R. Ortiz De Montellano, Evidence for the racial composition of Egypt comes from a variety of sources which found "a remarkable degree of constancy in the population of Egypt over a period of 5,000 years".[27] Professor Stephen Quirke, an Egyptologist at University College London, says that “There has been this very strong attempt throughout the history of Egyptology to disassociate ancient Egyptians from the modern population.” While there have been a number of influxes of people from outside Egypt, he suggested that the impact is over-stated, as thousands of soldiers had taken part in the Arab Invasion of Egypt in the 7th century, but they were still vastly outnumbered by the resident population of about six million.[106] In the publication "Clines and clusters versus Race: a test in ancient Egypt and the case of a death on the Nile", American anthropologist C. Loring Brace discussed the controversy concerning the race of the Ancient Egyptians. Brace argued that the "Egyptians have been in place since back in the Pleistocene and have been largely unaffected by either invasions or migrations".[107] Even Cheikh Anta Diop has called the belief that Arab invasions caused mass racial displacement into sub-Saharan Africa a “figment of the imagination".[108]

Culture

[edit]Supporters of the Black theory saw the Aethiopians and Egyptians as racially and culturally similar,[58][109] while others felt that the ancient Egyptians and Aethiopians were two ethnically distinct groups.[110] This is one of the most popular and controversial arguments for this theory.[10]: 21, 26 [111] At the 1974 UNESCO conference, Professor Vercoutter remarked that, in his view, "Egypt was African in its way of writing, in its culture, and in its way of thinking."[10]: 31 According to Diop, historians are in general agreement that the Aethiopians, Egyptians, Colchians, and people of the Southern Levant were among the only people on Earth practicing circumcision, which confirms their cultural affiliations, if not their ethnic affiliation.[112][11]: 112, 135–138 The Egyptian (adolescent) style of circumcision was different from how circumcision is practiced in other parts of the world, but similar to how it is practiced throughout the African continent.[113] "Ancient writings discuss (Egyptian) circumcision in religious terms"[114] and a 6th Dynasty tomb shows circumcision being performed by a "circumcising priest, rather than a physician."[115] "The practice of circumcising by religious, rather than medical, authorities is still common throughout Africa today."[113] Furthermore, in both ancient Egypt and modern Africa, young boys were circumcised in large groups.[116]

Circumcision was practiced in Egypt at a very early date. Strouhal mentions that "the earliest archaeological evidence for circumcision was found in the southern Nile Valley and dates from the Neolithic period, some 6000 years ago". The remains of circumcised individuals are cited as proof.[114] Similarly, Doyle states "It is now thought that the Egyptians adopted circumcision much earlier" (than the confirmed 2400 BC date), "from peoples living further south in today's Sudan and Ethiopia, where dark-skinned peoples are known to have practised circumcision".

Stephen Howe notes that "In their lists of supposed proofs for ancient Egypt's 'Negro origin', neither Diop nor those who followed his hypothesis later mentioned the dog that conspicuously didn't bark, to invoke the timeworn Sherlock Holmes cliche: Material culture." He argues that if cultural contact and direct influence across the Sahara and down the whole length of the Nile valley had been considerable, one would expect to find material objects of Egyptian origin across archaeological sites in Sub-saharan regions. Yet these hardly exist.[117]

Biblical Ham, blackness, and Ham's offspring

[edit]According to Diop, Bernal, and other scholars, "Ham was the ancestor of Negroes and Egyptians." According to Bernal, "the Talmudic interpretation that the curse of Ham (the father of Canaan and Mizraim, Egypt) was blackness was widespread."[56] According to Foster, "throughout the Middle Ages and to the end of the eighteenth century, the Negro was seen by Europeans as a descendant of Ham."[118] Ham was the father of Mizraim (the Hebrew word for Egypt), Phut, Kush, and Canaan. For Diop, Ham means "heat, black, burned" in Hebrew, an etymology which became popular in the 18th century.[119] Kush is positively identified with black Africa. Furthermore, "If the Egyptians were Negroes, sons of Ham...it is not by chance that this curse on the father of Mesraim, Phut, Kush, and Canaan, fell only on Canaan."[11]: 5–9 A review of David Goldenberg's The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity and Islam states that Goldenberg "argues persuasively that the biblical name Ham bears no relationship at all to the notion of blackness and as of now is of unknown etymology".[120]

At the UNESCO symposium in 1974, Professor Devisse said "there remained a variable proportion of Egyptians represented with negro features and colouring", even after adjusting for the "biblical tradition (descendants of Ham) and allegorical representations...(Hades, Night)."[10]: 42–43 [56]: 52–53 Professor Devisse provided examples, such as "a third of the participants...around the table of Joseph."[10]: 42–43 Regarding the realism in the costumes portrayed, he went on to say about the "black Egyptians", "the negroes, who were clearly differentiated from Egyptians wearing beards and turbans...were in many cases (black Egyptians) were carrying spears and wore a 'panther skin' leaving the right shoulder bare."[10]: 42–43 In conclusion, he said "it was very difficult to interpret these documents, but "nevertheless, they reflected a 'northerner's view' of the Egyptians which was not consistent with the standard 'white-skinned' theory."[10]: 42–43

Kemet

[edit]| km biliteral | kmt (place) | kmt (people) | |||||||||

|

|

|

Ancient Egyptians referred to their homeland as Kmt (conventionally pronounced as Kemet).

According to Diop, the Egyptians referred to themselves as "Black" people or kmt, and km was the etymological root of other words, such as Kam or Ham, which refer to Black people in Hebrew tradition.[10]: 27 [11]: 246–248 Diop,[121] William Leo Hansberry,[121] Aboubacry Moussa Lam[122] and other supporters of the Black Egyptian hypothesis have argued that the name kmt or Kemet was derived from the skin color of the Nile valley people, which Diop et al. claim was black.[10]: 21, 26 [123][10]: 27, 38, 40 The claim that the Ancient Egyptians had black skin has become a cornerstone of Afrocentric historiography,[121] but it is rejected by most Egyptologists.[50]

Mainstream scholars hold that kmt means "the black land" or "the black place", and that this is a reference to the fertile black soil which was washed down from Central Africa by the annual Nile inundation. By contrast the barren desert outside the narrow confines of the Nile watercourse was called dšrt (conventionally pronounced deshret) or "the red land".[121][124] Raymond Faulkner's Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian translates kmt into "Egyptians",[125] Gardiner translates it as "the Black Land, Egypt".[126]

At the UNESCO Symposium in 1974, Professors Sauneron, Obenga, and Diop concluded that KMT and KM meant black.[10]: 40 However, Professor Sauneron clarified that the Egyptians never used the adjective Kmtyw to refer to the various black peoples they knew of, they only used it to refer to themselves.[103]

Ancient art

[edit]

Diop saw the representation of black people in Egyptian art and iconography throughout Egyptian history. University of Chicago scholars state that the skin pigment used in Egyptian paintings to refer to Nubians can range "from dark red to brown to black".[127][128] This can be observed in paintings from the tomb of the Egyptian Huy, as well as Ramses II's temple at Beit el-Wali.[129] Also, Snowden indicates that Statius spoke of "red Ethiopians" and Romans had accurate knowledge of "negroes of a red, copper-colored complexion...among African tribes".[88]

Professors Vercoutter, Ghallab and Leclant stated that "Egyptian iconography, from the 18th Dynasty onward, showed characteristic representations of black people who had not previously been depicted; these representations meant, therefore, that at least from that dynasty onward the Egyptians had been in contact with peoples who were considered ethnically distinct from them."[103]

Depictions of Egyptians in art and artifacts are rendered in sometimes symbolic, rather than realistic, pigments. As a result, ancient Egyptian artifacts provide sometimes conflicting and inconclusive evidence of the ethnicity of the people who lived in Egypt during dynastic times.[130][131] Najovits states that "Egyptian art depicted Egyptians on the one hand and Nubians and other blacks on the other hand with distinctly different ethnic characteristics and depicted this abundantly and often aggressively. The Egyptians accurately, arrogantly and aggressively made national and ethnic distinctions from a very early date in their art and literature."[132] He continues that "There is an extraordinary abundance of Egyptian works of art which clearly depicted sharply contrasted reddish-brown Egyptians and black Nubians."[132]

Barbara Mertz writes in Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt: "The concept of race would have been totally alien to them [Ancient Egyptians] ...The skin color that painters usually used for men is a reddish brown. Women were depicted as lighter in complexion, perhaps because they didn’t spend so much time out of doors. Some individuals are shown with black skins. I cannot recall a single example of the words “black,” “brown,” or “white” being used in an Egyptian text to describe a person." She gives the example of one of Thutmose III’s “sole companions”, who was Nubian or Cushite. In his funerary scroll, he is shown with dark brown skin instead of the conventional reddish brown used for Egyptians[51]

Ahmose-Nefertari is an example of the controversy. In most depictions of Ahmose-Nefertari, she is pictured with black skin,[133][134] while in some instances her skin is blue[135] or red.[136] In 1939 Flinders Petrie said "an invasion from the south...established a black queen as the divine ancestress of the XVIIIth dynasty"[137][89] He also said "a possibility of the black being symbolic has been suggested."[138] Petrie also stated that "Nefertari must have married a Libyan, as she was the mother of Amenhetep I, who was of fair Libyan style."[139] In 1961 Alan Gardiner, in describing the walls of tombs in the Der el-Medina area, noted in passing that Ahmose-Nefertari was "well represented" in these tomb illustrations, and that her countenance was sometimes black and sometimes blue. He did not offer any explanation for these colors, but noted that her probable ancestry ruled out that she might have had black blood.[135] In 1974, Diop described Ahmose-Nefertari as "typically negroid."[140]: 17 In the controversial book Black Athena, the hypotheses of which have been widely rejected by mainstream scholarship, Martin Bernal considered her skin color in paintings to be a clear sign of Nubian ancestry.[141] In more recent times, scholars such as Joyce Tyldesley, Sigrid Hodel-Hoenes, and Graciela Gestoso Singer, argued that her skin color is indicative of her role as a goddess of resurrection, since black is both the color of the fertile land of Egypt and that of the underworld."[133] Singer recognizes that "Some scholars have suggested that this is a sign of Nubian ancestry."[133] Singer also states a statuette of Ahmose-Nefertari at the Museo Egizio in Turin which shows her with a black face, though her arms and feet are not darkened, thus suggesting that the black coloring has an iconographic motive and does not reflect her actual appearance.[142]: 90 [143][133]

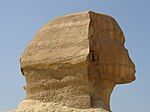

Sculpture and the Sphinx

[edit]

This debate is best characterized by the controversy over the Great Sphinx of Giza.[11]: 6–42 Scholars supportive of the Black Egyptian hypothesis reviewed Egyptian sculpture from throughout the dynastic period and concluded that the sculptures were consistent with the phenotype of the black race.[10]: 53–54

Around 1785 Volney stated, "When I visited the sphinx...on seeing that head, typically Negro in all its features, I remembered...Herodotus says: "...the Egyptians...are black with woolly hair"..."[11]: 27 Another early description of a "Negroid" Sphinx is recorded in the travel notes of a French scholar, who visited in Egypt between 1783 and 1785, Constantin-François Chassebœuf[144] along with French novelist Gustave Flaubert.[145] A similar description was given in the "well-known book"[118] by Baron V. Denon, where he described the sphinx as "the character is African; but the mouth, the lips of which are thick."[146] Following the 18-19th century writings, numerous scholars, such as DuBois,[14][147][148] Diop,[11]: Frontispiece, 27, 43, 51–53 and Asante[149] have characterized the face of the Sphinx as Black, or "Negroid".

The identity of the model for the Great Sphinx of Giza is unknown.[150] Virtually all Egyptologists and scholars currently believe that the face of the Sphinx represents the likeness of the Pharaoh Khafre, although a few Egyptologists and interested amateurs have proposed several different hypotheses.[citation needed]

David S. Anderson writes in Lost City, Found Pyramid: Understanding Alternative Archaeologies and Pseudoscientific Practices that Van Sertima's claim that "the sphinx was a portrait statue of the black pharoah Khafre" is a form of "pseudoarchaeology" not supported by evidence.[151] He compares it to the claim that Olmec colossal heads had "African origins", which is not taken seriously by Mesoamerican scholars such as Richard Diehl and Ann Cyphers.[152]

Queen Tiye is an example of the controversy, as some such as American journalist Michael Specter and Felicity Barringer's 'revisionists' describe her sculpture as that of a "black African",[153] while Yurco describes her mummy as having 'long, wavy brown hair, a high-bridged, arched nose and moderately thin lips."[154]

Qustul artifacts

[edit]Scholars from the University of Chicago Oriental Institute excavated at Qustul (near Abu Simbel – Modern Sudan), in 1960–64, and found artifacts which incorporated images associated with Egyptian pharaohs. From this Williams concluded that "Egypt and Nubia A-Group culture shared the same official culture", "participated in the most complex dynastic developments", and "Nubia and Egypt were both part of the great East African substratum".[155] Williams also wrote that Qustul in Nubia "could well have been the seat of Egypt's founding dynasty".[156][157] Diop used this as further evidence in support of his Black Egyptian hypothesis.[158] David O'Connor wrote that the Qustul incense burner provides evidence that the A-group Nubian culture in Qustul marked the "pivotal change" from predynastic to dynastic "Egyptian monumental art".[159]

However, "most scholars do not agree with this hypothesis",[160] as more recent finds in Egypt indicate that this iconography originated in Egypt not Nubia, and that the Qustul rulers adopted/emulated the symbols of Egyptian pharaohs.[161][162][163][164][165]

More recent and broader studies have determined that the distinct pottery styles, differing burial practices, different grave goods and the distribution of sites all indicate that the Naqada people and the Nubian A-Group people were from different cultures. Kathryn Bard further states that "Naqada cultural burials contain very few Nubian craft goods, which suggests that while Egyptian goods were exported to Nubia and were buried in A-Group graves, A-Group goods were of little interest further north."[166]

- ^ Lefkowitz, Mary R.; Rogers, Guy MacLean (2014-03-24). Black Athena Revisited. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-1-4696-2032-9.

- ^ Shaw, Ian (2004-07-22). Ancient Egypt: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-157840-3.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2006-06-22). Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-1421-0.

- ^ "Patterson properly noted that the "contributionist approach," now commonly called Afrocentric, does violence to the facts, is ideologically bankrupt, and is methodologically deficient. He pointed out that in many respects only a small part of the history of the African continent is relevant to the Afro-American experience, because it has been long established that the vast majority of American blacks came from the western coast of Africa. And he correctly observed that there is no justification for defining the term "black" to include all the swarthy peoples of Egypt and north Africa." [1]

- ^ "It is ironic that today much of Afrocentric writing about Egypt is based on the same evidence used by earlier Heliocentric authors. However, now the claim is that ancient Egypt was a black African civilization and that Egyptians (or at least the rulers and the cultural leaders) were negroid (Diop, 1974, 1981; Williams, 1974), No one disputes that Egypt is in Africa, or that its civilization had elements in common with sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in religion. However, the claim that all Egyptians, or even all the pharaohs, were black, is not valid. Most scholars believe that Egyptians in antiquity looked pretty much as they look today, with a gradation of darker shades toward the Sudan" [2]

- ^ Chowdhury, Kanishka (1997). "Afrocentric Voices: Constructing Identities, [Dis]placing Difference". College Literature. 24 (2): 35–56. ISSN 0093-3139. JSTOR 25112296.

- ^ "Afrocentrism | Definition, Examples, History, Beliefs, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-17.

- ^ Bay, Mia (2000). "The Historical Origins of Afrocentrism". Amerikastudien / American Studies. 45 (4): 501–512. ISSN 0340-2827. JSTOR 41157604.

- ^ Molefi Kete Asante, "Cheikh Anta Diop: An Intellectual Portrait" (Univ of Sankore Press: December 30, 2007)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 1-118. ISBN 978-0-520-06697-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. p. 1-288. ISBN 978-1-55652-072-3.

- ^ Bernal, Martin (1987). Black Athena. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. 63–75, 98–101, 439–443. ISBN 978-0-8135-1277-8.

- ^ "Tutankhamun was not black: Egypt antiquities chief". AFP. Sep 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Graham W. Irwin (1977-01-01). Africans abroad: a documentary history of the Black Diaspora in Asia, Latin …. ISBN 9780231039369. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Robert Schoch ,"Great Sphinx Controversy". robertschoch.net. 1995. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012., A modified version of this manuscript was published in the "Fortean Times" (P.O. Box 2409, London NW5 4NP) No. 79, February March, 1995, pp. 34, 39.

- ^ Grant, Michael (1972). Cleopatra: A Biography. Edison, NJ: Barnes and Noble Books. pp. 4, 5. ISBN 978-0880297257. Grant notes that Cleopatra probably had not a drop of Egyptian blood and "would have described herself as Greek," noting that had she been illegitimate her "numerous Roman enemies would have revealed this to the world."

- ^ Goldsworthy, Adrian Keith (2011), Antony and Cleopatra, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, pp. 8, 127–128, ISBN 978-0300165340. Goldworthy notes Cleopatra "was no more Egyptian culturally or ethnically than most residents of modern day Arizona are Apaches", that Greek was her native tongue, that it was "in Greek literature and culture she was educated," and that she wore the robes and headband of a Greek monarch.

- ^ Schiff, Stacy (2011). Cleopatra: A Life. UK: Random House. pp. 2, 42. ISBN 978-0316001946. Schiff writes Cleopatra was not dark-skinned, that "the Ptolemies were in fact Macedonian Greek, which makes Cleopatra approximately as Egyptian as Elizabeth Taylor", that her Ptolemaic relatives were described as "honey skinned", that she was part Persian, and that "an Egyptian mistress is a rarity among the Ptolemies."

- ^ Hugh B. Price ,"Was Cleopatra Black?". The Baltimore Sun. September 26, 1991. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ^ Charles Whitaker ,"Was Cleopatra Black?". Ebony. Feb 2002. Retrieved May 28, 2012. The author cites a few examples of the claim, one of which is a chapter entitled "Black Warrior Queens," published in 1984 in Black Women in Antiquity, part of The Journal of African Civilization series, in which a principal argument in favor of the hypothesis claims that Cleopatra called herself black in the Book of Acts, when she in fact did not and had died long before the New Testament. It draws heavily on the work of J.A. Rogers.

- ^ Mona Charen ,"Afrocentric View Distorts History and Achievement by Blacks". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. February 14, 1994. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ a b c Lefkowitz, Mary R; Rogers, Guy Maclean (1996). Black Athena Revisited. UNC Press Books. p. 162. ISBN 9780807845554. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

brace, egyptian, race.

- ^ a b c Bard, Kathryn A; Shubert, Steven Blake (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. p. 329. ISBN 9780415185899. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Stephen Howe (1999). Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes. p. 19. ISBN 9781859842287. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ a b Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār (1990). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. p. 43. ISBN 9780852550922. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ a b Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār (1990). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. p. 10. ISBN 9780852550922. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Montellano, Bernard R. Ortiz De (1993). "Melanin, afrocentricity, and pseudoscience". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 36 (S17): 33–58. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330360604. ISSN 1096-8644.

- ^ DuBois, W.E.B. (2003). The World and Africa. New York: International Publishers. pp. 81–147. ISBN 978-0-7178-0221-0.

- ^ Williams, Chancellor (1987). The Destruction of Black Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Third World Press. pp. 59–135. ISBN 978-0-88378-030-5.

- ^ a b Diop, Cheikh Anta (1981). Civilization or Barbarism. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 103–108. ISBN 978-1-55652-048-8.

- ^ Jackson, John G. (1970). Introduction to African Civilizations. New York, NY, USA: Citadel Press. pp. 60–156. ISBN 978-0-8065-2189-3.

- ^ Sertima, Ivan Van (1985). African Presence in Early Asia. New Brunswick, USA: Transaction Publishers. pp. 59–65, 177–185. ISBN 978-0-88738-637-4.

- ^ Bernal, Martin (1987). Black Athena. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. 63–75, 98–101, 439–443. ISBN 978-0-8135-1277-8.

- ^ Magbagbeola, Segun (2012). Black Egyptians: The African Origins of Ancient Egypt. United Kingdom: Akasha Publishing Ltd. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-09573695-0-4.

- ^ Muhly (2016). "Black Athena versus Traditional Scholarship". Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology. 3 (1): 83–110. doi:10.1558/jmea.v3i1.29853.

- ^ Snowden p. 117

- ^ "Four Unforgettable Scholars, Countless Gifts to the World". Journalofafricancivilizations.com. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Snowden p.116 of Black Athena Revisited"

- ^ Snowden, Jr., Frank M. (Winter 1997). "Misconceptions about African Blacks in the Ancient Mediterranean World: Specialists and Afrocentrists". Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics. 4 (3): 28–50. JSTOR 20163634.

- ^ Frank M. Snowden Jr. (1997). "Misconceptions about African Blacks in the Ancient Mediterranean World: Specialists and Afrocentrists" (PDF). Arion. 4: 28–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- ^ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 1–9, 134–155. ISBN 978-1-55652-072-3.

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita, S. O. Y. (1995). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships". International Journal of Anthropology. 10 (2–3): 107–123. doi:10.1007/BF02444602. S2CID 83660108.

- ^ Ryan A. Brown and George J. Armelagos, "Apportionment of Racial Diversity: A Review" Archived 2006-09-10 at the Wayback Machine, 2001, Evolutionary Anthropology, 10:34–40.

- ^ a b Stuart Tyson Smith (2001) The Oxford encyclopedia of ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Edited by Redford; Oxford University Press. p. 27-28

- ^ Bruce Trigger, 'Nubian, Negro, Black, Nilotic?', in Sylvia Hochfield and Elizabeth Riefstahl (eds), Africa in Antiquity: the arts of Nubia and the Sudan, Vol. 1 (New York: Brooklyn Museum, 1978).

- ^ Keita, S.O.Y. (Sep 16, 2008). "Ancient Egyptian Origins:Biology". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ a b Specter, Michael (1990-02-26). "WAS NEFERTITI BLACK? BITTER DEBATE ERUPTS". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- ^ Frank Yurco, "An Egyptological Review", 1996, in Mary R. Lefkowitz and Guy MacLean Rogers, Black Athena Revisited, 1996, The University of North Carolina Press, pp. 62–100.

- ^ "Afrocentrism More Myth Than History, Scholar Says". UC Davis. 2001-04-20. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ a b Bard, Kathryn A. "Ancient Egyptians and the Issue of Race". in Lefkowitz and MacLean rogers, p. 114

- ^ a b c Mertz, Barbara (2011-01-25). Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-208716-4.

- ^ a b Kemp, Barry J. (May 7, 2007). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilisation. Routledge. pp. 46–58. ISBN 9781134563883.

- ^ "Ancient Egyptians more closely related to Europeans than modern Egyptians, scientists claim". The Independent. 2017-05-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ a b "Reference Populations – Geno 2.0 Next Generation". National Geographic. genographic.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- ^ Lefkowitz, Mary R.; Rogers, Guy MacLean (2014-03-24). Black Athena Revisited. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-1-4696-2032-9.

- ^ a b c d Bernal, Martin (1987). Black Athena. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-8135-1276-1.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 2.104.2.

- ^ a b Snowden, Frank (1970). Blacks in Antiquity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 109.

- ^ a b Lefkowitz, Mary R.; Rogers, Guy MacLean (1996). Black Athena Revisited. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4555-4.

- ^ a b Lefkowitz, Mary R.; Rogers, Guy MacLean (1996). Black Athena Revisited. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4555-4.

- ^ T. James Luce, The Greek Historians, 2002, p. 26

- ^ Amoia, Professor Emeritus Alba; Amoia, Alba Della Fazia; Knapp, Bettina Liebowitz; Knapp, Bettina Liebowitz Knapp (2002). Multicultural Writers from Antiquity to 1945: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. p. 171. ISBN 9780313306877. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ David G. Farley (2010-11-30). Modernist Travel Writing: Intellectuals Abroad. p. 21. ISBN 9780826272287. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1981). Civilization or Barbarism. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. ISBN 978-1-55652-048-8.

- ^ Welsby, Derek (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London: British Museum Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7141-0986-2.

- ^ Heeren, A.H.L. (1838). Historical researches into the politics, intercourse, and trade of the Carthaginians, Ethiopians, and Egyptians. Michigan: University of Michigan Library. pp. 13, 379, 422–424. ASIN B003B3P1Y8.

- ^ Aubin, Henry (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press. pp. 94–96, 100–102, 118–121, 141–144, 328, 336. ISBN 978-1-56947-275-0.

- ^ von Martels, Z. R. W. M. (1994). Travel Fact and Travel Fiction: Studies on Fiction, Literary Tradition …. p. 1. ISBN 978-9004101128. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ Kenton L. Sparks (1998). Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Israel: Prolegomena to the Study of Ethnic …. p. 59. ISBN 9781575060330. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ David Asheri; Alan Lloyd; Aldo Corcella (2007-08-30). A Commentary on Herodotus. p. 74. ISBN 9780198149569. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ Jennifer T. Roberts (2011-06-23). Herodotus: A Very Short Introduction. p. 115. ISBN 9780199575992. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ Alan Cameron (2004-09-02). Greek Mythography in the Roman World. p. 156. ISBN 9780198038214. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ John Marincola (2001-12-13). Greek Historians. p. 34. ISBN 9780199225019. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ Amoia, Professor Emeritus Alba; Amoia, Alba Della Fazia; Knapp, Bettina Liebowitz; Knapp, Bettina Liebowitz Knapp (2002). Multicultural Writers from Antiquity to 1945: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. p. 171. ISBN 9780313306877. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ David G. Farley (2010-11-30). Modernist Travel Writing: Intellectuals Abroad. p. 21. ISBN 9780826272287. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ Alan B. Lloyd (1993). Herodotus. p. 1. ISBN 978-9004077379. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ Flemming A. J. Nielsen (1997-11-01). The Tragedy in History: Herodotus and the Deuteronomistic History. p. 41. ISBN 9781850756880. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ Herodotus: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide - Oxford University Press. Oxford University Press. 2010-05-01. p. 21. ISBN 9780199802869. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ Simson Najovits (2003). Egypt, the Trunk of the Tree, Vol.II: A Modern Survey of and Ancient Land. p. 320. ISBN 9780875862576. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Lefkowitz, Mary R.; Rogers, Guy MacLean (2014-03-24). Black Athena Revisited. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-1-4696-2032-9.

- ^ Palmer, Brian (2014-12-03). "How Realistic Is Exodus: Were Ancient Egyptians Pale-Skinned?". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- ^ Herodotus (2003). The Histories. London, England: Penguin Books. pp. 103, 119, 134–135, 640. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- ^ Rawlinson, George (2018). The Histories of Herodotus. Scribe Publishing. ISBN 978-1787801714.

black-skinned and have woolly hair

- ^ Snowden, Frank (1970). Blacks in Antiquity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 101, 104–106, 109.

- ^ Shavit, Yaacov (2001). History in Black: African-Americans in Search of an Ancient Past. London: Frank Cass Publishers. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-7146-5062-3.

- ^ Byron, Gay (2002). Symbolic Blackness and Ethnic Difference in Early Christian Literature. London and New York: Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-415-24369-8.

- ^ Najovits, Simson (2003). Egypt, Trunk of the Tree, Vol. II: A Modern Survey of and Ancient Land. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-256-9.

- ^ a b c Snowden, Frank (1970). Blacks in Antiquity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 3.

- ^ a b Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Neues Reich. Theben [Thebes]: Der el Medînet [Dayr al-Madînah Site]: Stuckbild aus Grab 10. [jetzt im K. Museum zu Berlin.], (1849 - 1856)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Davidson, Basil (1991). African Civilization Revisited: From Antiquity to Modern Times. Africa World Press.

- ^ Alan B. Lloyd (1993). Herodotus. p. 22. ISBN 978-9004077379. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Alan B. Lloyd (1993). Herodotus. ISBN 978-9004077379. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Lefkowitz, Mary R.; Rogers, Guy MacLean (1996). Black Athena Revisited. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4555-4.

- ^ Lefkowitz, Mary R; Rogers, Guy Maclean (1996). Black Athena Revisited. UNC Press Books. p. 118. ISBN 9780807845554. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

herodotus, melanchroes, Lefkowitz.

- ^ Egypt, the Trunk of the Tree: A Modern Survey of an Ancient Land, by Simson Najovits, pg 319

- ^ Cheikh Anta Diop, "Evolution of the Negro world", Présence Africaine, Vol. 23, no. 51 (1964), pp. 5–15.

- ^ Lefkowitz, Mary R.; Rogers, Guy MacLean (2014-03-24). Black Athena Revisited. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-1-4696-2032-9.

- ^ a b Howe, Stephen (1998). Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes. Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-873-9.

- ^ Chris Gray, Conceptions of History in the Works of Cheikh Anta Diop and Theophile Obenga, (Karnak House:1989) 11–155

- ^ Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār (1990). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. p. 33. ISBN 9780852550922. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Alain Ricard, Naomi Morgan, The Languages & Literatures of Africa: The Sands of Babel, James Currey, 2004, p.14

- ^ Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār (1990). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. p. 10. ISBN 9780852550922. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ a b c Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār (1990). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. p. 10. ISBN 9780852550922. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ "Slavery, Genocide and the Politics of Outrage". MERIP. 2005-03-06. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ James Newman, The Peopling of Africa: A Geographic Interpretation (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995), p. 79.

- ^ "Ancient Egyptians more closely related to Europeans than modern Egyptians, scientists claim". The Independent. 2017-05-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ Brace, C. Loring; Tracer, David P.; Yaroch, Lucia Allen; Robb, John; Brandt, Kari; Nelson, A. Russell (2005), "Clines and clusters versus 'Race': a test in ancient Egypt and the case of a death on the Nile", American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 36 (S17): 1–31, doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330360603

- ^ Cheikh Anta Diop, Precolonial Black Africa (New York, 1987), p. 102. Cited in Stephen Howe, Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes (London: Verso, 1998), p. 228.

- ^ Snowden, Frank (1970). Blacks in Antiquity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 119.

- ^ Lefkowitz, Mary R.; Rogers, Guy Maclean (1996). Black Athena Revisited. UNC Press Books. p. 389. ISBN 9780807845554. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

melanchroes.

- ^ Herodotus (2003). The Histories. London, England: Penguin Books. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- ^ English, Patrick T (January 1959). "Cushites, Colchians, and Khazars". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 18 (1): 49–53. doi:10.1086/371491. S2CID 161751649. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ a b Bailey, Susan (1996). Egypt in Africa. Indiana, USA: Indianapolis Museum of Art. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-253-33269-1.

- ^ a b Stouhal, Eugen (1992). Life of the Ancient Egyptians. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-977-424-285-4.

- ^ Ghalioungui, Paul (1963). Magic & Medical Science in Ancient Egypt. New York: Barnes & Noble. p. 95. ASIN B000IP45Z8.

- ^ Stracmans, M. (1959). Encore un texte peau connu relatif a la circoncision des anciens Egyptiens. Archivo Internazionale di Ethnografia e Preistoria. pp. 2:7–15.

- ^ Howe, Stephen (1999). Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes. Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-228-7.

- ^ a b Foster, Herbert J. (1974). "The Ethnicity of the Ancient Egyptians". Journal of Black Studies. 5 (2): 175–191. doi:10.1177/002193477400500205. JSTOR 2783936. S2CID 144961394.

- ^ Goldenberg, David M. (2005). The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (New ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0691123707.

- ^ Levine, Molly Myerowitz (2004). "David M. Goldenberg, The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d Shavit 2001: 148

- ^ Aboubacry Moussa Lam, "L'Égypte ancienne et l'Afrique", in Maria R. Turano et Paul Vandepitte, Pour une histoire de l'Afrique, 2003, pp. 50 &51

- ^ Herodotus (2003). The Histories. London, England: Penguin Books. pp. 134–135, 640. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- ^ Kemp, Barry J. (2006). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy Of A Civilization. Psychology Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-415-06346-3.

- ^ Raymond Faulkner, A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, Oxford: Griffith Institute, 2002, p. 286.

- ^ Gardiner, Alan (1957) [1927]. Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs (3 ed.). Griffith Institute, Oxford. ISBN 978-0-900416-35-4.

- ^ "Nubia Gallery". The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- ^ Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Neues Reich. Dynastie XVIII. Theben [Thebes]. Qurnet Murrâi [Blatt 3], linke Hinterwand [d]., (1849 - 1856)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York, NY: The Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 22–23, 36–37. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Charlotte Booth,The Ancient Egyptians for Dummies (2007) p. 217

- ^ a b 'Egypt, Trunk of the Tree, A Modern Survey of an Ancient Land, Vol. 2. by Simson Najovits pg 318

- ^ a b c d Graciela Gestoso Singer, "Ahmose-Nefertari, The Woman in Black". Terrae Antiqvae, January 17, 2011

- ^ Gitton, Michel (1973). "Ahmose Nefertari, sa vie et son culte posthume". École Pratique des Hautes études, 5e Section, Sciences Religieuses. 85 (82): 84. doi:10.3406/ephe.1973.20828. ISSN 0183-7451.

- ^ a b Gardiner, Alan H. (1961). Egypt of the Pharaohs: an introduction. Oxford: Oxford University press., p.175

- ^ https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/former-queen-ahmose-nefertari-protectress-royal-tomb-workers-deified

- ^ Petrie, Flinders (1939). The making of Egypt. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) p.155 - ^ Petrie, Flinders (1939). The making of Egypt. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) p.155 - ^ Petrie, Flinders (1939). The making of Egypt. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) p.155 - ^ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 1-118. ISBN 978-0-520-06697-7.

- ^ Martin Bernal (1987), Black Athena: Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization. The Fabrication of Ancient Greece, 1785-1985, vol. I. New Jersey, Rutgers University Press

- ^ Tyldesley, Joyce. Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2006. ISBN 0-500-05145-3

- ^ Hodel-Hoenes, S & Warburton, D (trans), Life and Death in Ancient Egypt: Scenes from Private Tombs in New Kingdom Thebes, Cornell University Press, 2000, p. 268.

- ^ Constantin-François Chassebœuf saw the Sphinx as "typically negro in all its features"; Volney, Constantin-François de Chasseboeuf, Voyage en Egypte et en Syrie, Paris, 1825, page 65

- ^ "...its head is grey, ears very large and protruding like a negro’s...the fact that the nose is missing increases the flat, negroid effect. Besides, it was certainly Ethiopian; the lips are thick.." Flaubert, Gustave. Flaubert in Egypt, ed. Francis Steegmuller. (London: Penguin Classics, 1996). ISBN 978-0-14-043582-5.

- ^ Denon, Vivant (1803). Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt. General Bonaparte. pp. 269–270.

the character is African, but the mouth, the lips of which are thick

- ^ W. E. B. Du Bois (2001-04-24). The Negro. ISBN 978-0812217759. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Black man of the Nile and his family, by Yosef Ben-Jochannan, pp. 109–110

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (1996). European Racism Regarding Ancient Egypt: Egypt in Africa. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-936260-64-8.

- ^ Hassan, Selim (1949). The Sphinx: Its history in the light of recent excavations. Cairo: Government Press, 1949.

- ^ Card, Jeb J.; Anderson, David S. (2016-09-15). Lost City, Found Pyramid: Understanding Alternative Archaeologies and Pseudoscientific Practices. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-1911-3.

- ^ Diehl 2004, p.112. Cyphers 1996, p. 156.

- ^ Specter, Michael (February 26, 1990). "Was Nefertiti Black? Bitter Debate Erupts". The Washington Post. The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

Queen Tiye, who also lived in the 14th century B.C., was much more clearly a black African.

- ^ Barringer, Felicity (February 5, 1990). "Ideas & Trends; Africa's Claim to Egypt's History Grows More Insistent". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ Williams, Bruce (2011). Before the Pyramids. Chicago, Illinois: Oriental Institute Museum Publications. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- ^ "The Nubia Salvage Project | The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago". oi.uchicago.edu.

- ^ O'Connor, David Bourke; Silverman, David P (1995). Ancient Egyptian Kingship. ISBN 978-9004100411. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1991). Civilization or Barbarism. Chicago, Illinois, USA: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 103–105. ISBN 978-1-55652-048-8.

- ^ O'Connor, David (2011). Before the Pyramids. Chicago, Illinois: Oriental Institute Museum Publications. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- ^ Shaw, Ian (2003-10-23). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. p. 63. ISBN 9780191604621. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ D. Wengrow (2006-05-25). The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa …. p. 167. ISBN 9780521835862. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Peter Mitchell (2005). African Connections: An Archaeological Perspective on Africa and the Wider World. p. 69. ISBN 9780759102590. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id%3DAR1ZZO6niVIC%26pg%3DPA194%26dq%3DQustul+burner%26hl%3Den%26sa%3DX%26ei%3DLo7-UITgFYqa0QWNnYDYDA%26ved%3D0CEcQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=Qustul%20burner&f=false. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[dead link] - ^ László Török (2009). Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region Between Ancient Nubia and Egypt …. p. 577. ISBN 978-9004171978. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life of the Nubians. ISBN 9780313325014. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, by Kathryn A. Bard, 2015, p. 110