User:Marcd30319/Task Force 71

| Task Force 71 (TF-71) | |

|---|---|

| Active | 15 March 1943 – present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Task Force |

| Role | Naval special warfare operations * SEAL * SWCC * SDVT Explosive ordnance disposal |

| Part of | United States Seventh Fleet |

| Garrison/HQ | Naval Base Guam |

Task Force 71 (TF-71) is a United States Navy task force assigned to the United States Seventh Fleet.

Current operations

[edit]Currently, TF-71 is the designation for Navy Special Warfare Unit One which includes all Naval Special Warfare (NSW) units and Explosive Ordnance Disposal Mobile Units (EODMU) assigned to Seventh Fleet. This task force is based in Guam.

Task Force 71, a subordinate task force of the 7th Fleet, is the Navy Special Warfare (NSW) unit. NSW is comprised of (as of Sep 2012) approximately 8,900 total personnel, including more than 2,400 active-duty Special Warfare Operators, known as SEALs, 700 Special Warfare Boat Operators, also known as Special Warfare Combatant-craft Crewmen (SWCC), 700 reserve personnel, 4,100 support personnel and more than 1,100 civilians. Naval Special Warfare Command in San Diego, Calif., leads the Navy?s special operations force and the maritime component of United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), headquartered at MacDill Air Force Base, Tampa, Fla. NSW Groups command, train, equip and deploy components of NSW Squadrons to meet the exercise, contingency, and wartime requirements of the regional combatant commanders, theater special operations commands and numbered fleets located around the world. Additionally, they receive support from permanently deployed NSW units in Guam, Bahrain and Germany. NSW Squadrons are built around deployed SEAL Teams and include senior leadership, SEAL Delivery Vehicle Teams, Special Boat Teams, and support technicians such as mobile communications teams, tactical cryptologic support and explosive ordnance disposal specialists. Naval Special Warfare Squadrons are among the most responsive, versatile and effective force packages fighting the global war on terrorism today. Because SEALs are experts in special reconnaissance and direct action missions ? the primary skill sets needed to combat terrorism ? NSW is postured to fight a globally-dispersed enemy, whether ashore or afloat, before they can act. NSW forces can operate in small groups and have a continuous presence overseas with their ability to quickly deploy from Navy ships, submarines and aircraft, overseas bases and forward-based units. The proven ability of NSW forces to operate across the spectrum of conflict and in operations other than war, and provide real-time, first-hand intelligence offer decision makers immediate and multiple options in the face of rapidly changing crises around the world.[1]

Historical antecedents

[edit]World War Two

[edit]Southwest Pacific submarine offensive

[edit]The surviving U.S. Asiatic Fleet submarines were withdrawn to Australia in March 1942. Eventually, 20 submarines were initially based at Fremantle, Western Australia (pictured), and five submarines were based at Brisbane, Queensland. By November 1942, Submarine Squadrons Eight and Ten were transferred from Pearl Harbor to Brisbane, and Submarine Squadron Two was shifted from Fremantle to Brisbane. The Australian-based submarine force concentrated on isolating the Japanese naval bases on Truk and Rabaul from the rest of the Japanese Empire.[2][3]

Effective 15 March 1943, United States Naval Forces Southwest Pacific (SUBSOWESPAC) was re-designated United States Seventh Fleet, and United States Submarines Force Southwest Pacific (see map for details) based in Fremantle was re-designated Task Force 71. Rear Admiral Ralph W. Christie remained as Commander Submarines Southwest Pacific (COMSUBSOWESPAC), as well as Commander Task Force 71 (CTF-71)[4][5]

During Summer 1943, Submarine Squadron Six was rotated back to the United States, but Submarine Squadrons Twelve and Sixteen joined Task Force 71 for a total of 22 submarines assigned to TF-71.[6] By mid-1944, Task Force 71 established two advance bases at Manus in the Admiralty Islands as well as Mios Woendi located southeast of Biak, Indonesia.[7][8] Also, by this time, a total of 40 fleet submarines were operated by Task Force 71.[9] An additional ten Anglo-Dutch submarines joined Task Force 71 in Fall 1944.[10] TF-71 submarines were serviced by submarine tenders Fulton, Pelias, Bushnell, Howard W. Gilmore, and Anthedon.[11]

According to American historian Samuel Eliot Morison in his seminal History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, between February 1943 to May 1944, Task Force 71 submarines completed 101 war patrols. TF-71 submarines sank 96 large Japanese merchant ships as well as 55 small craft. The total Japanese merchant marine tonnage sunk by Task Force 71 was 473,300 long tons (480,900 t). TF-71 submarines also sank the submarine I-182, four destroyers, and four small warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy during this period.[12]

In September 1944, as the Allies prepared for its upcoming Philippines campaign, TF-71 submarines supported allied landings on Palau and Morotai.[13] As part of the lead-up to the Allied invasion of Leyte on October 1944, a dozen TF-71 submarines were deployed to monitor the movement of Japanese submarines.[14] During the ensuing naval Battle of Leyte Gulf, TF-71 submarines were credited with sinking two Takao-class heavy cruisers and heavily damaged another Takao-class heavy cruiser.[15][16]

Effective 15 November 1944, Task Force 72 and its submarines based in Brisbane were merged into Task Force 71, with TF-72 being dissolved on that date.[17] On 30 December 1944, Admiral Christie was relieved by Rear Admiral James Fife.[18] By 13 March 1945, Task Force 71 completed the relocation of its new main operating base from Fremantle to Subic Bay, the Philippines.[19] Initially, Task Force 71 concentrated on eliminating the remaining Japanese surface warships operating out of Singapore with mixed results.[20] Subsequently, during the closing months of World War Two, TF-71 submarines sank Japanese merchant shipping in the Gulf of Siam and South China Sea as Allied forces plugged the so-called Luzon bottleneck and continued to tighten its air-sea blockade on the Japanese home islands.[7][21]

- Task Force 71 results, March 1943 – August 1945[22]

| Year | Submarines | Wartime estimates | JANAC assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patrols | Losses | Ships sunk | Tonnage sunk | Ships sunk | Tonnage sunk | |

| 1943 | 44 | 5 | 96 | 2,745,795 long tons (2,789,857 t) | 61 | 277,240 long tons (281,690 t) |

| 1944 | 34 | 6 | 203 | 1,240,200 long tons (1,260,100 t) | 151 1/2 | 836,116 long tons (849,533 t) |

| 1945 | 25 | 2 | 74 | 267,000 long tons (271,000 t) | 54 | 128,407 long tons (130,468 t) |

| Totals | 103 | 13 | 373 | 4,252,995 long tons (4,321,242 t) | 266 1/2 | 1,241,763 long tons (1,261,689 t) |

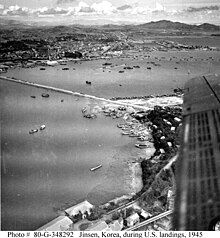

Allied occupation of the Korean peninsula

[edit]With the defeat of the Japanese Empire imminent, U.S. military planners met in Manila, the Philippines, 18–19 August 1945 to examine post-war operations, including the allied occupation of formerly Japanese-held territories throughout the Pacific Theater of Operations, including China, the Korean peninsula, and the home islands of Japan itself.[23]

Following that conference, on 21 August 1945, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the Commander-in-Chief U.S. Pacific, reported to Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, the Chief of Naval Operations, on the future operations of the U.S. Seventh Fleet and its support of the eventual allied occupation of China and Korea. Nimitz's concept of operations included a North China Naval Force. Its primary mission was to support the allied occupation of Korea. Its area of responsibility would encompass the Shantung-Chinwangtao region in China, as well as the Yellow Sea and the Gulf of Pohai. The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff approved Nimitz's overall concept of operations for the Seventh Fleet in China and Korea, including a Northern China Naval Force, on 29 August 1945.[24][25]

On 26 August 1945, U.S. Seventh Fleet Operation Plan 13-45 designated Task Force 71 as this North China Naval Force, with 75 warships assigned.[26] This newly re-designated task force was commanded by Rear Admiral Francis S. Low.[27] Admiral Low had commanded Cruiser Division 16, consisting of the battle cruisers Alaska and Guam, during the Okinawa invasion and participated in carrier air strikes against Kyushu, southern Honshu, and the Nansei Shoto Islands.[28][29][30]

On 28 August 1945, the U.S. Seventh Fleet came under the operational control of Admiral Nimitz's U.S. Pacific Fleet, and its fleet commander, Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, ordered fleet units to steam to the Yellow Sea in a show of force prior to the landing of U.S. Army ground forces in Korea.[31]

On 1 September 1945, Task Force 71 steamed off Tsingtao and carried out similar show-the-flag operations along the western coast of Korea as well as in the Pohai Gulf. The main body of Task Force 71 consisted of the battle cruisers Alaska and Guam, as well as heavy cruisers San Francisco, New Orleans, Minneapolis, and Tuscaloosa of Cruiser Division 6 under the command of Rear Admiral Jerauld Wright.[32][33]

Cold War

[edit]During the Cold War and afterwards, Task Force 71 operated as the Command and Coordination Force for the U.S. Seventh Fleet with its flagship being the command ship USS Blue Ridge, based at U.S. Fleet Activities Yokosuka, Japan, since 1979.[34][35]

Vietnam War

[edit]

Following the Vũng Rô Bay Incident of 16 February 1965, the United States Navy initiated Operation Market Time to stop the flow of troops and supplies transported by sea from North Vietnam to South Vietnam during the Vietnam War. During the first half of 1965, the U.S. Seventh Fleet operated the U.S. component of the Operation Market Time, the Vietnam Patrol Force, which was given the designation of Task Force 71.[36]

The Saigon-headquartered Naval Advisory Group served as the Market Time liaison between the U.S. Seventh Fleet, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, the South Vietnamese Navy, and Task Force 71. The five U.S.-Vietnamese coastal surveillance centers set up at Danang, Qui Nhon, Nha Trang, Vung Tau, and An Thoi coordinated the actual Market Time operations. To improve mutual understanding and communication, U.S. and Vietnamese naval officers sailed in the vessels of the other naval service.[36]

On 11 March 1965, Task Force 71 began the inaugural Market Time patrol when the U.S. Seventh Fleet destroyers Higbee and Black began operating off the South Vietnam coastline.[37][38] During the ensuing four months, the Black patrolled the coast of South Vietnam from Saigon to Danang, with the exception of port visits for repairs, supplies, and ammunition. On 9 May and 4 July, the Black left Market Time patrols to provide naval gunfire support of U.S. troops ashore. The destroyer Black concluded Market Time patrols on 16 July.[39] The destroyer Higbee departed Task Force 71 in May to participated in recovery operations for the NASA manned Gemini 4 orbital space mission in the western Pacific Ocean.[40]

On 31 July 1965, the Vietnam Patrol Force (Task Force) was transferred from the U.S. Seventh Fleet to the U.S. Naval Advisory Group, which activated the Coastal Surveillance Force (Task Force 115). The Seventh Fleet continued to provide logistic and administrative support to Operation Market Time. On 1 April 1966, Naval Forces, Vietnam was established, relieving the Naval Advisory Group of the responsibility for Market Time operations. Also, the U.S. naval support activities at Danang and Saigon took over logistic and administrative duties for Operation Market Time. In July 1967, Task Force 115 shifted its headquarters from Saigon to Cam Ranh Bay.[36]

North Korea

[edit]

The Korean DMZ Conflict, also referred to as a Second Korean War, was a series of low-level armed clashes between North Korean forces and the forces of South Korea and the United States, largely occurring between 1966 and 1969 at the Korean DMZ.[41] On 21 January 21 1968, in the most overt incident to date, North Korean commandos attempted unsuccessfully to assassinate the South Korea president Park Chung-hee at the presidential residence Blue House in Seoul, South Korea.

In January 1968, the capture of Pueblo by a North Korean patrol boat led to a diplomatic crisis. Enterprise was ordered to operate near South Korean waters for almost a month.

- Task Force 71 (1968)

On 14 April 1969, tensions with North Korea flared again as a North Korean aircraft shot down an Lockheed EC-121 Warning Star that was on a reconnaissance patrol over the East Japan Sea from its base at Atsugi, Japan. The entire 31-man crew was killed. The US responded by activating Task Force 71 (TF 71) to protect future such flights over those international waters. Initially, the Task Force was to comprise Enterprise, Ticonderoga, Ranger, and Hornet with a screen of cruisers and destroyers. Enterprise arrived on station with TF 71 in late April after completion of repairs. The ships for TF 71 came mostly from Southeast Asia duty. This deployment became one of the largest shows of force in the area since the Korean War.

- Task Force 71 (1969)

| Carrier Groups | Screening Force | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aircraft Carriers | Carrier Air Wing | Battleships / Cruisers | DLG / DDG | Destroyers | Destroyers / Destroyer Escorts |

| USS Enterprise (CVAN-65)[Note 6] | Carrier Air Wing 9 | USS New Jersey (BB-62) | USS Sterett (DLG-31) | USS Meredith (DD-890) | USS Gurke (DD-783) |

| USS Ranger (CVA-61)[Note 7] | Carrier Air Wing 2 | USS Chicago (CG-11) | USS Dale (DLG-19) | USS Henry W. Tucker (DD-875) | USS Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729) |

| USS Ticonderoga (CVA-14)[Note 8] | Carrier Air Wing 16 | USS Oklahoma City (CLG-5) | USS Mahan (DLG-11) | USS Perry (DD-844) | USS John W. Weeks (DD-701) |

| USS Hornet (CVS-12)[Note 9] | ASW Air Group 57 | USS Saint Paul (CA-73) | USS Parsons (DDG-33) | USS Ernest G. Small (DD-838) | USS Radford (DD-446) |

| —— | —— | —— | USS Lynde McCormick (DDG-8) | USS Shelton (DD-790) | USS Davidson (DE-1045) |

| —— | —— | —— | —— | USS Richard B. Anderson (DD-786) | —— |

KAL 007 Incident

[edit]

Korean Air Lines Flight 007 was a scheduled Korean Air Lines flight from New York City to Seoul via Anchorage. On 1 September 1983, the Boeing 747-2B5B airliner serving the flight was shot down by a Soviet Su-15 interceptor near Moneron Island, west of Sakhalin Island, in the Sea of Japan. All 269 passengers and crew aboard were killed. The aircraft was en route from Anchorage to Seoul when it flew through prohibited Soviet airspace around the time of a U.S. reconnaissance mission (See map for details.). In the immediate aftermath of this incident, on 8 September 1983, U.S. President Ronald Reagan directed that the U.S. search and rescue (SAR) operation in international waters continue with the full cooperation and coordination with South Korea and Japan. Also, President Reagan directed that a joint American-Japanese request be sent to the Soviet government to expand this U.S.-led operation to include Soviet territorial waters and airspace.[42]

Task Force 71 operated the Search and Rescue/Salvage Operations for Korean Air Lines Flight 007 shot down by the Soviets off Sakhalin Island on 1 September 1983. On that day, Rear Admiral William A. Cockell as Commander Task Force 71 and a skeleton staff flew by helicopter from Japan to the frigate Badger that was stationed off Vladivostock at time of the flight.[43] On 9 September 1983, Admiral Cockell and his TF-71 staff was transferred to the destroyer Elliot to assume duties as Officer in Tactical Command (OTC) of the Search and Rescue (SAR) effort. The surface search began immediately and continued to 13 September. U.S. underwater operations began on 14 September. With no longer any hope of finding survivors, on 10 September 1983, Task Force 71's mission had been reclassified "Search and Salvage" operation from a "Search and Rescue". On 17 October 1983, ear Admiral Walter T. Piotti, Jr., relieved Rear Admiral William Cockell of command of Task Force 71 and its Search and Salvage mission.

As a result of Cold War tensions, the subsequent search and rescue operations of the Soviet Union were not co-ordinated with those of the United States, South Korea, and Japan. Consequently no information was shared, and each side endeavored to harass or obtain evidence to implicate the other.[44] The flight data recorders were the key pieces of evidence sought by both factions, with the United States insisting that an independent observer from the ICAO be present on one of its search vessels in the event that they were found.[45] International boundaries are not well defined on the open sea, leading to numerous confrontations between the large number of opposing naval ships that were assembled in the area.[46]

In addition to the ships listed below, there were numerous Japanese Maritime Safety Agency patrol boats and South Korean vessels involved in this Search and Rescue operation.

- Task Force 71 (1983)[47]

| Salvage Ships | Search and Rescue Force | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USN / USCG | Chartered | Cruisers | Destroyers | Frigates | Fleet Auxiliaries |

| USS Conserver (ARS-39) | Kaiko-Maru 3 | USS Sterett (CG-31) | USS Callaghan (DDG-994) | USS Stark (FFG-31) | USS Wichita (AOR-1) |

| USNS Narragansett (T-ATF-167) | Kaiko-Maru 7 | —— | USS Towers (DDG-9) | USS Brooke (FFG-1) | USS Hassayampa (AO-145) |

| USCGC Munro (WHEC-724) | MV Ocean Bull | —— | USS Elliot (DD-967) | USS Badger (FF-1071) | —— |

Notes

[edit]- Footnotes

- Citations

- ^ http://usacac.army.mil/cac2/call/thesaurus/toc.asp?id=36716

- ^ Edward C. Whitman (Spring 2001). "Winning to Victory: The Pacific Submarine Strategy in World War II, Part I: Retreat and Retrenchment". Undersea Warfare: The Official Magazine of the U.S. Submarine Force. Submarine Warfare Division (N87). Retrieved 2014-01-29.

Whitman, Winning to Victory 1.

- ^ Blair, Clay (1975, 2001). Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 192, 197, 217, 339, 349–350, 359–362. ISBN 978-1-55750-217-9. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

Hereafter referred to as: Blair. Silent Victory

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (2004). History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 6: Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, 22 July 1942-1 May 1944. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-59114-552-3. Retrieved 2014-01-24.

Hereafter referred to as: Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier

- ^ Jones, David. (2004). U.S. Subs Down Under: Brisbane 1942-1945. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-59114-644-5.

Hereafter referred to as: Jones & Nunan. U.S. Subs Down Under

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Blair & Silent Victory, p. 475.

- ^ a b Edward C. Whitman (Summer 2001). "Winning to Victory: The Pacific Submarine Strategy in World War II, Part II: Winning Through". Undersea Warfare: The Official Magazine of the U.S. Submarine Force. Submarine Warfare Division (N87). Retrieved 2014-01-24.

Whitman, Winning to Victory 2.

- ^ Blair & Silent Victory, p. 711.

- ^ Blair & Silent Victory, p. 694.

- ^ Morison & Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 742–743.

- ^ Blair & Silent Victory, pp. 475, 846.

- ^ Morison & Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Morison & Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 734–736.

- ^ Blair & Silent Victory, p. 571.

- ^ Blair & Silent Victory, p. 766.

- ^ "Preliminary Action Report of Engagements in Leyte Gulf and off Samar Island on 25 October, 1944". HyperWar Foundation. November 18, 1944. Retrieved 2014-01-24.

- ^ Jones & Nunan & U.S. Subs Down Under, p. 233.

- ^ Blair & Silent Victory, pp. 814–815.

- ^ Blair & Silent Victory, pp. 845–846.

- ^ Blair & Silent Victory, pp. 780, 794, 846–855

- ^ Blair & Silent Victory, pp. 855–856.

- ^ Blair & Silent Victory, pp. 552, 818, 924–925, 936–937, 946–949, 956–957, 961–962, 966–967, 972–975.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (2004). History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 14: Victory in the Pacific, 1945. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-1-59114-579-0. Retrieved 2014-07-19.

Hereafter referred to as: Morison, Victory in the Pacific

- ^ Morison, Victory in the Pacific, p. 355.

- ^ Jeffrey G., Barlow (2009). From Hot War to Cold: The U.S. Navy and National Security Affairs, 1945-1955. Palo Alto, California: Stanford University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-080475-666-2. Retrieved 2014-07-09.

Hereafter referred to as: Bartow. From Hot War to Cold.

- ^ Marolda, Edward J. (October 2011). "Asian Warm-up to the Cold War". Naval History. 25 (5). United States Naval Institute: 27–28. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- ^ Bartow. From Hot War to Cold, p. 129.

- ^ Morison, Victory in the Pacific, pp. 21, 307, 310, 385.

- ^ "Admiral Francis S. Low, US Navy 15 August 1894 - 22 January 1964". Naval History & Heritage Command. 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

Adapted from the biographical sketch for Admiral Francis S. Low, Navy Biographies Branch, 23 July 1956; now part of the Modern Biography Files, Navy Department Library, Naval History & Heritage Command.

- ^ "United States Pacific Fleet Organization – 1 May 1945". Naval History & Heritage Command. 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ Bartow. From Hot War to Cold, pp. 129–130.

- ^ "Report of Surrender and Occupation of Japan dated 9 May 1946" (PDF). Retrieved 11 July 2014.

Part III - THE SURRENDER AND OCCUPATION OF KOREA, p. 111

- ^ Key, Jr., David M. (2001). Admiral Jerauld Wright: Warrior among Diplomats. Manhattan, Kansas: Sunflower University Press. pp. 226–232. ISBN 978-0897452519.

- ^ Polmar, Norman (2005). The Naval Institute Guide to The Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet, 18th ed. Annapolis, Maryland: U.S. Naval Institute Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-59114-678-8.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ "Blue Ridge". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Edward J. Marolda (8 November 1997). "By Sea, Air, and Land: An Illustrated History of the U.S. Navy and the Vietnam War". Chapter 3: The Years of Combat, 1965 - 1968. Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 2014-01-26.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2012). Almanac of American Military History, Volume 4. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 1977. ISBN 978-1-59884-530-3.

- ^ Polmar, Norman (2006). Chronology of the Cold War at Sea 1945-1991. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-155750-685-6.

Hereafter referred to as: Polmar. Chronology of the Cold War at Sea.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Black". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Higbee". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Mitchell Lerner (December 2010). ""Mostly Propaganda in Nature:" Kim Il Sung, the Juche Ideology, and the Second Korean War" (Document). The North Korea International Documentation Project.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ "National Security Decision Directive 102: U.S. Response to Soviet Destruction of KAL Airliner" (PDF). National Security Council and National Security Planning Group Meetings - 1983. TheReaganFiles. September 5, 1983. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

See points 4 and 5 under Diplomacy and Justice under the Action section.

- ^ Shootdown, R.W. Johnson, Viking, N.Y. 1985,pg.194

- ^ Uriel Rosenthal, Michael T. Charles, Paul 't Hart (1989). Coping with Crises: The Management of Disasters, Riots, and Terrorism. C.C. Thomas. ISBN 0-398-05597-1. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "ICAO Council Examines Follow-Up of Korean Air Lines Incident" (PDF) (Press release). International Civil Aviation Organization. October 1983. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ Isaacson et al., 1983

- ^ KAL 007: the Cover-up, David Pearson, Summit Books, 1987, N.Y.,ppg. 237,239