User:Laurdurham/sandbox/samplesandbox

This is where I will draft my article

Jane Sharp (c.1641 -- unknown) was a 17th-century English midwife. Her work The Midwives Book: or the Whole Art of Midwifery Discovered, published in 1671, was the first on the subject to be published by an Englishwoman.[1]

Life

[edit]Little is known of Sharp's life beyond her publication. She is thought to be born in 1641 in Shrewsbury, county town of Shropshire, England, near Wales.[2] The title page of her book claims that she had been a "practitioner in the art of midwifry above thirty years."[3] She is believed to have practiced in London, although Sharp’s name does not appear in any Church of England registration books or in witness signatures on any of the almost 500 London midwifery certificates surviving from 1661-1669.[2] Neither does Sharp appear on any registrations of the Catholic Church at the time. Sharp may have been Puritan, which would account for her ability to read and write (Unlike Catholics or Anglicans, Puritan woman were often literate[4]).[5] Her ability to write and her ability to travel to and from London suggests that she may have been a economically advantaged, though it is unclear whether she received formal education.[6]

While no marriage records are available, it appears that Jane Sharp had either a daughter or daughter-in-law. Midwife Anne Parrott of St. Clement Danes in London, bequeathed a small sum to "Sarah Sharp the daughter of Jane Sharp."[7]

Given how little is known about her life, including any record of her death, some believe that Jane Sharp is a pseudonym,[2] as it was common for Early Modern women writers to use pseudonyms to publish their work.[7][8]

Profession as a midwife

[edit]Though it is unknown whether Sharp received any formal education, Sharp claims to have practised midwifery for 30 years.[5] As a midwife, Sharp may have been educated, but unlike male surgeons of the time, midwives rarely received formal medical training.[7] Instead, midwifery was learned through practice. Midwifery was one of a few available professions for women in the Early Modern period, as it was sanctioned by both Anglican and Catholic parishes throughout sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[8] Though men were beginning to enter the field, Early Modern English social norms saw birthing as a feminine practice, and discouraged males to pursue midwifery.[9] Because the vast majority of births in Sharp's time took place in the mother's home, childbirth was generally presided over by a female midwife.[10] Amongst her practical advice, she urges women to adopt a comfortable position during labour. This included having an upright birth on a birthing chair.[10]

Beyond her profession as a midwife, Sharp's writing extended her professional work into the realm of medical text publication. While women dominated the role of midwife, men received formal education to become physicians and surgeons.[7][9] Her ability to write to women about their own medical issues using both the accepted medical knowledge of the period and her own practical experience advanced medical knowledge as well as women's status as in healing professions.[11]

The Midwives Book

[edit]The first edition of The Midwives Book, or, The Whole Art of Midwifry Discovered was published in 1671, with three subsequent editions published in 1674, 1724, and 1725.[2] The first two editions were published by Simon Miller[10] while the third and fourth editions were published posthumously by John Marsall as The Compleat Midwife's Companion.[2] Published as a small octavo, The Midwives Book was a lengthy text of 95,000 words. It sold for 2 shillings, 6 pence.[2][10] While the book's length and price suggest that Sharp's target audience was an upper-class readership, the book was primarily aimed at practicing midwives, as the book begins with the following direct address:

TO THE MIDWIVES OF ENGLAND.

Sisters. I Have often sate down sad in the Consideration of the many Miseries Women endure in the Hands of unskilful Midwives; many professing the Art (without any skill in Anatomy, which is the Principal part effectually necessary for a Midwife) meerly for Lucres sake. I have been at Great Cost in Translations for all Books, either French, Dutch, or Ita∣lian of this kind. All which I offer with my own Experience. Humbly begging the assistance of Almighty God to aid you in this Great Work, and am

Your Affectionate Friend

Jane Sharp.

— Jane Sharp, The Midwives Book, Preface

The first edition of The Midwives Book is dedicated to Sharp's "much esteemed and ever honoured friend," Lady Elleanour Talbutt,[10] an unmarried sister of John Talbot, 10th Earle of Shrewsbury, further suggesting Sharp's connection to Western England.[2] The title page of the first edition of The Midwives Book states that Sharp was a "Practitioner in the Art of midwivry above thirty years" at the time of printing.[10] Later editions, including the posthumous The Compleat Midwife's Companion, published in 1724 states that Sharp had practiced "above forty years."[12]

Purpose and use

[edit]The Midwives Book was published in 1671 and instructed women how to conceive a child, maintain pregnancy, prepare for childbirth, birth a child, and how to care for a woman after childbirth. Given its comprehensive scope, the book served as a manual not only for midwives but also for women and men to learn about anatomy and sexuality. While most midwifery manuals of the period were published by men, some of whom had never witnessed childbirth,[7][13] Sharp's book focused on the practices of midwifery, drawing on practical experience. While providing in her book a practical guide to midwifery, she uses it also as a platform for her views on women's education, male midwives, and female sexuality.[14] Her book was also notable because it was written in the vernacular; Sharp is careful to avoid "hard words" which “are but the shell” of knowledge.[10]: 12

Organization

[edit]

The manual was divided into six parts, specifically:

- I. An Anatomical Description of the Parts of Men and Women. This section explained the anatomy of male and female sexual organs and their use in reproduction.

- II. What is requisite for Procreation: Signes of a Womans being with Child, and whether it be Male or Female, and how the Child is formed in the womb. This section described sexual reproduction and offered advice for how to conceive, and described signs of pregnancy and the process of gestation.

- III. The causes and hinderance of conception and Barrenness, and of the paines and difficulties of Childbearing with their causes, signes and cures. This section offers advice on how to promote fertility as well as how to care for pregnant women.

- IV. Rules to know when a woman is near her labour, and when she is near conception, and how to order the Child when born. This section offers guidance on the preparation of women for labor, offering roles and responsibilities for midwives and both mothers and fathers, as well as how to examine and care for a newly born child.

- V. How to order women in Childbirth, and of several diseases and cures for women in that condition. This section instructs midwives on how to manage childbirth under a variety of conditions and circumstances, as well as how to care for women with various ailments that might occur during pregnancy and delivery.

- VI. Of Diseases incident to women after conception; Rules for the choice of a nurse; her office; with proper cures for all diseases Incident to young Children. This section addresses a variety of aspects of post-natal care for both the woman and her newborn child, including nutritional support for child, breastfeeding techniques, and care for different types of venereal diseases, most notably syphilis.[15]

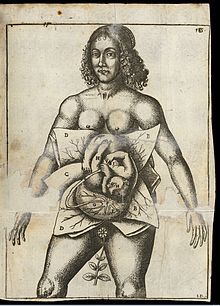

Jane Sharp's depiction of fetus(es) in utero.

Writing style

[edit]Sharp's writing draws from accepted medical knowledge of the time, suggesting that she had access to and was well read in scientific and medical publications.[16] By writing in the vernacular, she made available both surgical and pharmacological techniques to women training to become midwives so that they need not depend on male physicians when birthing complications or emergencies arose.[11]

Sharp also employs the technique of commonplacing,[17] a familiar science writing practice of the time.[18] Similar to scrapbooks, commonplace books included information from other sources to be remembered as well as notes, quotations, tables, drawings, etc. The use of commonplacing enabled Sharp to integrate existing academic knowledge about anatomy, childbirth, and women's health while adding her own practical expertise. In doing so, she is able to both affirm and correct medical knowledge about women's anatomy, reproduction, and childbirth.[1][9] For instance, Sharp cites the ancient scientific understanding of the humorous body, developed and used by Aristotle, Hippocrates, and Galen, that presumed a woman's menstrual blood feeds a fetus. She then explains the dominant hypothesis of the day from "Fernelius, Pliny, Columells, and Columbus" who asserted that menstrual blood poisoned a fetus. Drawing on her own observations, she corrects both theories by asserting, "But to answer all… Hippocrates was mistaken…if the child be not fed with this blood what becomes of this blood when women are with child?"[10]: 143–144 By commonplacing directly from academic sources, Sharp not only asserts her knowledge into established medical traditions but also legitimates the expertise that comes from practicing midwifery to expand existing medical knowledge.[19]

Through these stylistics techniques, Sharp challenged and improved upon the academic methods trained male physicians by providing empirically based corrections based on her practical experience.[9] At the same time she created an accessible guide to women's anatomy that called into the question the authority of academic knowledge.[9][19]

Personal beliefs

[edit]In her book, Sharp combines the medical knowledge of the time with personal anecdotes and argued that the profession of midwifery should be reserved for women, at a time when male midwives were becoming more common. She urged female midwives to learn various surgical and pharmacological techniques instead of depending on male physicians when complications and emergencies arose. Although the knowledge gained by men from universities might carry more prestige, it usually lacked the basis of experience of female midwives. Culpeper's admission that he had never attended an actual birth serves a prime example.[10] Sharp stresses that practice and experience used in combination with medical texts produces the best clinician, not theoretical knowledge alone: '"It is not hard words that perform the work, as if none understood the Art that cannot understand Greek. Words are but the shell, that we often break our Teeth with them to come at the kernel."'[1]

In strongly opposing the trend towards male midwives, she expressed a belief that women were naturally inclined toward midwifery. She acknowledged that men had better access to education and so tended to have greater theoretical knowledge of anatomy and medicine, but she decried male midwives' lack of practical understanding. She called for female midwives to end their reliance on male doctors entirely, proposing instead that they learn how to deal with emergencies and complications themselves.[14] Complaining of the inadequacies of female education, she noted that "women cannot attain so rarely to the knowledge of things as many may, who are bred up in universities."[16]

Other midwifery manuals

[edit]The Midwives Book drew on contemporary sources, particularly Nicholas Culpepper's A Directory for Midwives (1651) and Daniel Sennert's Practical Physick (1664). However, in doing so, Sharp corrected their misinformation and changed their tone to reflect her own protofeminist views.

The tradition of midwifery manuals in England began with The Byrth of Mankynd, a 1540 translation of Eucharius Rösslin's Der Rosengarten.[13] From then until the publication of The Midwives Book, midwifery manual writing was dominated by men without practical midwifery experience. In lieu of consulting midwives and mothers, they acquired information from ancient Greek translations and other midwifery manuals written by men without experience. These writers exhibited a grotesque fascination with female sexuality.[10] Their writings demonstrate their understanding of women as hypersexual, excessive, weak, and inferior beings, valuable solely in terms of their usefulness to men.[13]

The introduction to the 1999 publication of The Midwives Book states that "For all the parallels between The Midwives Book and its male equivalents, then, the differences in detail result in a fundamental shift in the way sexuality and gender are conceptualized."

Impact

[edit]The Midwives Book: or the Whole Art of Midwifry Discovered gave invaluable advice at a time when midwifery faced change. It sold excellently and its popularity indicates that it was most likely a household item in the 18th century. The book is still in print as a primary source of information about women, childbirth and sexuality during the Renaissance.

The children's book The Midwife's Apprentice features a character based on Jane Sharp.

- ^ a b c Bosanquet, Anna (2009). "Inspiration from the past (1) Jane Sharp" (PDF). The Practising Midwife. 12 (8): 33–35.

- ^ a b c d e f g Moscucci, Ornella (2004-09-23). Sharp, Jane (fl. 1641–1671), midwife. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- ^ McClive, Cathy (October 2001). "Jane Sharp, The midwives book or the whole art of midwifry discovered, edited by Elaine Hobby, New York and Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1999, pp. xliii, 323, illus., £30.00 (hardback 0-19-508652-X)". Medical History. 45 (4): 540–541. doi:10.1017/s0025727300068459. ISSN 0025-7273.

- ^ Willen, Diane (1992). "Godly Women in Early Modern England: Puritanism and Gender" (PDF). Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 43: 561–580.

- ^ a b Beal, Jane (Autumn 2013). "Jane Sharp: A Midwife of Renaissance England". Midwifery Today. 107.

- ^ "Jane Sharp (1641–71)".

- ^ a b c d e Evenden, Doreen (2000). "Introduction". The Midwives of Seventeenth-Century London. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 10. ISBN 0521661072.

- ^ a b "Women Writers in Context". www.wwp.northeastern.edu. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ a b c d e "Swaddling England: How Jane Sharp's Midwives Book Shaped the Body of Early Modern Reproductive Tradition". Early Modern Studies Journal. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sharp, Jane; Hobby, Elaine (1999). The Midwives Book: or the Whole Art of Midwifery Discovered (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508653-8; pbk

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b Fissell, Mary E. (October 2009). "Women in healing spaces". The Cambridge Companion to Early Modern Women's Writing. doi:10.1017/ccol9780521885270.011. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Jane Sharp, The compleat midwife's companion, 1724, retrieved 2020-05-18

- ^ a b c Hobby, Elaine (2001). "Secrets of the Female Sex: Jane Sharp, the female reproductive body, and early modern midwifery manuals". Women's Writing (8:2): 201–212.

- ^ a b Bosanquet, Anna (September 2009). "Inspiration from the Past: Jane Sharp". The Practicing Midwife. 12 (8).

- ^ Sharp, Jane; Hobby, Elaine (1999). The Midwives Book: or the Whole Art of Midwifery Discovered (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. xvii–xxix. ISBN 0-19-508653-8; pbk

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b Ogilvie, Marilyn; Harvey, Joy (2000). The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science, vol. 2, L–Z. Routledge. p. 1181. ISBN 978-0-415-92038-4.

- ^ Mackay, Elizabeth (March 2019). "Rhetorical Intertextualities of M. R.'s The Mothers Counsell, or Live Within Compasse, 1630". Women Writers Online. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Eddy, M.D. (June 2010). "Tools for Reordering: Commonplacing and the Space of Words in Linnaeus's Philosophia Botanica". Intellectual History Review. 20 (2): 227–252. doi:10.1080/17496971003783773. ISSN 1749-6977.

- ^ a b Bicks, Caroline (2007). "Stones Like Women's Paps: Revising Gender in Jane Sharp's Midwives Book". Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies. 7: 1–27 – via JSTOR.

![Title Page of The midwives book, or, the whole art of midwifry discovered by Jane Sharp (1641)]]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/Title_Page_of_The_midwives_book%2C_or%2C_the_whole_art_of_midwifry_discovered_by_Jane_Sharp_%281641%29.jpg/250px-Title_Page_of_The_midwives_book%2C_or%2C_the_whole_art_of_midwifry_discovered_by_Jane_Sharp_%281641%29.jpg?auto=webp)