User:Kingofmapps/sandbox1

Presidents of the United States of America Up Until Secession

[edit]| No. | Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Term | Party | Election | Vice President | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

George Washington (1732–1799) |

April 30, 1789 – March 4, 1797 |

Unaffiliated | 1788–1789 1792 |

John Adams | |

| 2 |

|

Alexander Hamilton (1755 or 1757–1825) |

March 4, 1797 – March 4, 1809 |

Federalist | 1796 1800 1804 |

Timothy Pickering | |

| 3 |

|

Rufus King (1755–1827) |

March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1825 |

Federalist | 1808 1812 1816 1820 |

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney John Jay | |

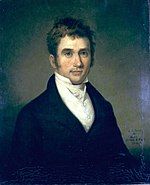

| 4 |

|

Jesse B. Thomas (1777–1853) |

March 4, 1825 – March 4, 1830 |

Democratic- Republican (party collapsed) |

1824 | John Holmes Vacant after December 25, 1827 | |

| 5 |

|

Henry Clay (1777–1852) |

March 4, 1831 – March 4, 1839 |

National Republican | 1830 1834 |

Theodore Frelinghuysen Daniel Webster | |

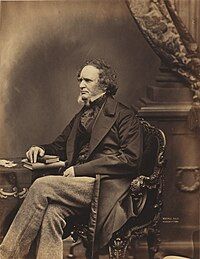

| 6 |

|

John Armstrong Jr. (1758–1843) |

March 4, 1839 – April 1, 1843 |

National Republican | 1838 1842 |

Edward Everett | |

| 7 |

|

Edward Everett (1794–1865) |

April 2, 1843 – March 4, 1847 |

National Republican | Inaugurated

after death in office |

Millard Fillmore | |

| 8 |

|

John Branch Jr. (1782–1863) |

March 4, 1847 – March 4, 1855 |

Democratic | 1846 1850 |

John M. Berrien | |

| 9 |

|

Robert Toombs (1810–1885) |

March 4, 1855 – March 4, 1868[a] |

Democratic | 1854 1860 1864 |

Alexander Stephens | |

| New England secedes, beginning the American Civil War on January 7, 1865 | |||||||

The Serene Republic of New England

[edit]

The Serene Republic of New England (SRNE), also referred to at different points in history as the The United States of New England (USNE), or the Unitary Republic of New England (URNE), is an unrecognized breakaway state which was realized until the end of the American Civil War, in the New England region of the United States. It declared secession on January 7, 1865. It has existed in the form of a government-in-exile in Toronto, Canada since the surrender of the Honorable Army of New England in 1872. During it's mainland existence, consisted of three provinces (four counting those that never existed in actuality), which took up the present American states of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, (unified into the Province of Carver) Maine, and Vermont and New Hampshire (which were unified into the Province of Chittenden.)

For a period of seventeen years following the election of Southern Democrat and staunch supporter of slavery, John Branch, economic and political turmoil had been commonplace throughout the states which made up New England, with a lack of federal funding and representation lead to the few industries which New Englanders were proficient with, those being shipbuilding, fishing, and subsistence farming, remaining unfocused and discouraged. Furthermore, the economic plans of Branch and the succeeding president, Georgian planter and senator Robert Toombs, with New England's natural aversion to agriculture, offered little aid, in a move which Toombs later publicized as "draining the abolition out of them."

The Civil War began formally on January 12, 1865, when troops of the Honorable Army of New England launched a raid into upstate New York, beginning a brief campaign referred to as the Battle of Albany. Though the New Englander troops were pushed out of the state, this then led to the establishment of the Province of Laurentia, claiming rightful governance over all of Upstate New York. The Civil War lasted until 1872, though after the capture of Boston in 1868, and relocation of the capital to Montpelier, fighting decreased in scale and intensity. Maine was captured in the latter half of 1869 after a landing operation was coordinated from Port Clyde, which had been occupied by Unionist troops since the beginning of the war. The New Englander army led by Joseph Hooker surrendered once Montpelier was surrounded after the Battle of Barre. The British Empire had offered, throughout the course of the war, varying amounts of assistance to New England, and prior to the capture of Boston plans had been drafted for recognition of the state. Canadian officials allowed President Charles Sumner, numerous other high-ranking politicians, and over 15,000 Vermonters and New Hampshirites to flee to Quebec, where the government in-exile was first established, before being moved to Toronto, where it has remained since.

After the war, during the Reconstruction era, the former New England states were readmitted formally in 1875, after the 13th Amendment was passed, enshrining slavery as a right of the people until it was repealed by the 20th Amendment in 1891. New Englander Nationalism was generally soured in the view of the American public, as an ideology up until the early twentieth century, when the Sumnerite Party was formed by suffragette and radical Republican Jessie Sumner in 1926, wherein which she would later run in the 1928 Presidential Election, and became the first woman to receive an electoral vote for president. New Englanders and their descendants in Oregon, Ontario, and the Rust Belt utilize symbolism and the flag of the Serene Republic in order to signify opposition to Conservative ideologies and a rebellion against the Democratic party's ideology.

Causes and Secession

[edit]A long period of political stability had made the lives of New Englanders quite difficult in the time prior to secession, this being primarily the conflict between the Northern Democrats and National Republicans. Republicans were popular in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, with the urban centers such as Boston, Augusta, Montpelier, being occupied by members of the Republican elite, typified by the political hold of the 'Boston Brahmin', whom were typically Anglican or Episcopalian, while Irish Catholics and poor laborers would vote for the Democrats. Tensions would often boil over, with many Republican senators and politicians delivering fiery speeches, told to be reminiscent of Brimstone preachers, in favor of the Republican agenda in the states, while Democrats would remain stagnant in office, offering support to the Democratic agenda while not speaking out about slavery, and relying upon connections with the more powerful bloc of Southern Democrats.

Within the preceding years of secession, tensions had flared on several occasions, with the main noted incident being the lynching of Robert Rantoul Jr. Rantoul was a prominent Democrat congressman in the north, known for his charisma and care for the poor. He was a House Representative for Massachusetts's 2nd district. Upon discovering the Republican loss in the 1854 Presidential Election, a crowd of angry Republicans had formed a militia, lead by former free-stater Edward L. Eudora, and led a raiding party into a celebration which Rantoul and several other local politicians had been attending. Rantoul was found, stripped, shot several times, and posthumously hung, with the word 'slaver' carved into his chest.

This exacerbated already worsening tensions, and though Eudora and several other members of the party were hung in accordance with state law, a controversy emerged as whether or not to bury Eudora with military honors, as he had been a corporal in the army and served in the Second Seminole War. Eventually, in a move which for a time, made Branch's administration unpopular, he used an executive order to end the lawsuit about the issue, Eudora vs. Lee, and granted Eudora's body typical military honors. This led to general and plaintiff Robert E. Lee resigning from his post in protest, and despite Branch already being a lame duck, it further exemplified the differences between Branch and Toombs, and increased his popularity among Northern Democrats, who felt personally attacked by Branch's order.

Tensions would only worsen when Toombs took office, as he vehemently defended slavery, and openly endorsed and funded the campaigns of pro-slavery candidates in states that were previously not tread in, such as Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Iowa, while overtures were made to legalize slavery in the New Mexico Territory, and a plan proposed to turn California into three separate states, including one that would be slave-holding. New Englanders, having been some of the staunchest abolitionists, due to their Puritan origins, took offense, though due to the power which Southern Democrats held over congress and the presidency, most wider attempts to limit the expansion of slavery were met with defeat. A coalition of Republicans was formed, known as the Caliphony Caucus, though it failed to garner a large margin to get much done at all, especially as it pertained to the issue of slavery. Pennsylvania and Ohio Republicans were rather lax on slavery, believing it necessary though an outdated practice, while those of New England would speak strongly against it.

This eventually culminated in the Republican campaign in 1864, which was considered a 'last ditch effort' for the party. The National Republican dynasty which had dominated the political scene for the four terms preceding Branch's election had failed to meet many of the initial goals of the party, and the vast majority of the progress which it did manage to co-opt was undone. Thus, the Republicans put forward candidate John C. Frémont, hoping to hinge their campaign on Frémont's reputation as a wild-man explorer, who would not settle, and would push forward the aims of the Republican party. Though, confidence was lost in his campaign as his image worsened. Democratic politicians, especially in New York City (see: Tammany Hall) began paying off newspapers to publicize his court marital during the Mexican-American War, and reports of his massacres of Native Americans, portraying it's victims with the 'noble savage' myth. Though confidence had been exerted in the campaign toward the beginning, it became quickly clear the fate of the election.

Around this period, Charles Sumner would gather around fifty Republican senators, mayors, representatives, governors from the New England states, and eastern Upstate New York at the Boston City Hall, where the idea of secession was first permissed as a plausible reaction to a Republican loss in the presidential election and a minority congressional elections afterward. The Declaration of the Creation of the Serene Republic of New England was first drafted at the meeting over a period of several days, though was concealed, unsigned in Sumner's personal study awaiting the election results. It is alleged that when the congregation gathered again to view the election results as they were declared, Sumner stood up and threw his hat down, yelling "What's the damn point!" before then putting forward the idea of an independent New England, though this is almost certainly false with the previously stated knowledge, and has no independent corroboration. Historians generally agree that while upset, orderly, the statesmen were independently summoned to sign the drafted document, though all agreed not to release the document or speak of it until the election was verified on January 6.

In the remaining months, several allegations of voter fraud were circulated, so much so that Congress formed an independent committee to investigate the issue. Besides the discovery of 26,000 false Democratic votes from New York, which was relatively commonplace due to the Tammany Hall's policy of forcing repeat voting and intimidation, the election results were certified as expected, with a Republican loss in the electoral college, and in the popular vote by a margin of around 18%, or 740,000 votes. Accordingly, the following day, January 7, 1865, at 2:31 AM, the Serene Republic declared independence from the Union.

Foreign Affairs, Debate On Governmental Structure, & The First Months of War

[edit]

When Sumner and his coalition had declared independence, their first goal was to seek legitimacy and recognition from other nations, believing that if they could secure foreign recognition and support, it would be able to negate what they lacked in numbers and training, and thus sent Henry A. Holmes to London, Austin Abbott to Paris, and Edward John Phelps to Mexico City. Individually, they all received a stale reception, especially so in Mexico, who feared American retribution, feeling that they could not sustain another war with the United States, and thus sent Phelps to Newark, New Jersey. without recognition or comment at all about New England's declaration of independence. Phelps was subsequently arrested, though not charged with any crime until the Battle of Albany commenced on January 12, where he remained in detention for treason for the duration of the war.

When Abbott arrived in Paris, the diplomats of Napoleon III were unsure how to approach the issue. Relations had been at a hastily formed stalemate for around seventy years due to President Alexander Hamilton's disagreement with the values of the French Revolution, and he and his successor's opposition to Napoleon, which were worsened when an undeclared war had forced the imperial ambitions of Napoleon III out of Mexico, though the diplomatic corps believed that inevitably, the Union would provide them cotton which they required for the textile industry, and revenge on the United States would make matters worse. Thus, the French recognized them as a belligerent, though declined any official comment or aid to the Serene Republic.

The only diplomat which made any headway was Holmes. Britain had begun the process of cultivating cotton in India, and thus didn't have to rely on American cotton, and the Civil War seemed an opportunity to retake the territory of the Thirteen Colonies. and despite initially being neutral on the issue, Britain would secretly send 12,000 Canadian troops over the course of the war, around twenty officers and generals to observe and advise, including Crimean War officer Charles George Gordon, and the HMS Warrior, though they never officially recognized or aligned themselves with the Serene Republic. British-American relations would never truly recover post-war until John J. Pershing was elected in 1924, and further decayed in the late nineteenth century when Britain was the primary pressuring force which forced them to abolish slavery in 1891.

The Serene Republic had numerous other diplomatic relations throughout the course of the war, with positive relations being maintained with Prussia, Bavaria, Italy, the Qing, the Netherlands, and the Tokugawa Shogunate, though none recognized them, with the exception of the Netherlands from 1867-1869. Hostile relations and condemnations were issued from the Ottoman Empire, Brazil, Spain, and Portugal. The abolitionist and anti-slavery attitudes which New England seceded with were prominent in Western Europe during the time, who viewed chattel slavery as a primitive and cruel practice were reflected in the foreign view of the Civil War, with the European public expressing interest in the war, and New England's successes, so much so that the most printed newspaper at the time, The Times, had a section dedicated to the war until 1870.

| The Sumner cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Charles Sumner | 1865-1874 |

| Vice President | Hannibal Hamlin | 1865-1874 |

| Secretary of State | Sidney Perham | 1865-1874 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | John B. Page | 1865-1872 |

| George W. Tew | 1872-1874 | |

| Secretary of War | Oliver Otis Howard | 1865-1874 |

| Attorney General | John Appleton | 1865-1874 |

| Postmaster General | Montgomery Blair | 1865-1874 |

| Secretary of the Navy | Thomas Wentworth Higginson | 1865-1869 |

| Gideon Welles | 1869-1872 | |

| Charles Henry Davis | 1872-1874 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | George B. Loring | 1865-1874 |

| Secretary of Commerce and Labor | Arthur Sewall | 1865-1874 |

Though, domestic issues were not resolved. Sumner, upon appointing Joseph Hooker as Major General of the Honorable Army of New England, called a constitutional convention on January 11, which would continue for the following four days. Sumner originally proposed an amicable agreement, which would form a government similar to that of the United States, containing a bicameral legislature, supreme court, presidency and vice presidency, and a cabinet, with an election occurring every six years. Though, once the Civil War had begun, and when New Englander troops were pushed from New York by early February, paranoia plagued the assembly. Sumner called officials back to the capital on February 10, and proposed an amended provisional constitution, which would grant the presidency a larger sum of the powers, and prohibit elections for the office of the presidency until the conclusion of the war. This was disputed and criticized by many delegates, who stated that it was a violation of the Democratic principles which the nation had declared independence for in the first place.

Despite their criticisms, a motion to instate the provisional constitution passed by a margin of twenty-two delegates, out of the total sixty-six, with Sumner declared the unitary President of the Serene Republic, with Hannibal Hamlin declared his vice president, and the cabinet organized. The first cabinet meeting, held on February 14, was allegedly the most contentious, with Secretary of War, Oliver Otis Howard, was very nearly bludgeoned by the first Secretary of the Navy, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, over what was supposedly a plan to perform a naval landing upon New York City, which Howard proposed, though Higginson strongly opposed, as they were still attempting to press Unionist ships in Boston and Maine's naval yards, and did not have nearly enough coordination to stage such an attack.

Though in the Battle of Albany, Hooker's troops had secured a few victories and begun exploiting guerrilla tactics, the state militias combined were not nearly enough to overwhelm the Union garrisons in the manner in which it was anticipated. The militias had been using M1841 rifled muskets, as opposed to the more modern muskets which the troops stationed along forts in Upstate New York had been carrying, alongside the Henry repeating rifle, which posed a threat which the militia's had no way to counter besides hit-and-run tactics, and utilizing what little artillery they had to inflict losses from a distance. In order to give themselves more legitimacy in the area, and open up the prospect of reentry into New York at some point, Sumner declared the existence of the Province of Laurentia, led by Republican House Representative, Reuben Fenton, whom would govern from Boston.

Secretary of War Howard was not the first choice for the position, in fact, Joseph Hooker was the choice favored by Sumner personally, and the one most often discussed by Hamlin and the Congress, however, Hooker wished to be in direct command, and despite promises he would see action independently, there seemed to be no other option but to place him as commander of the Honorable Army. While there was no greater shortage of West Point educated officers, the issue was skill and a lack of experience. Most generals were of a new generation, and those who were not were either not loyal to the Serene Republic or had never faced combat before. Thus, Oliver Otis Howard was chosen, a West Point educated officer who had commanded forces in the American Indian Wars, and served a stint with the Shanghai Volunteer Corps, where in which he commanded a force of around eighty marines during the Battle of Muddy Flat. This choice was questioned by Qing ambassadors, however, did not seriously affect relations.

Upon assuming his role, and after witnessing the failures of the militia's began a series of reform, including the creation of a dark green standard uniform which was mass-produced for the army, adopting the smuggled British Pattern 1859 Indian Service rifles, with a focus on artillery. This, in combination with receiving officers to train troops and oversee battle, allowed for the militia's to become far more organized, and brought New England it's first total victory at the Battle of Shaftsbury on February 21, when an excursion in southern Vermont was halted, with Unionists troops outnumbered 2-1, and without cavalry or artillery support, the Honorable Army was able to quickly flank and devastate the Unionists, a large blow to Unionist morale. Historians often point out the Union loss as the beginning of an understanding that the war was not going to be easy, nor was it likely to be short.

Internal Politics, The Carver Campaign, Naval Battles and Métis Intervention (1865-1868)

[edit]The United States government did not officially recognize or make any due public comment about the secession until the loss of the Battle of Shaftsbury, where in a speech on February 17, Toombs would mention a 'rebellion in our northeastern states and territories' at an occasion at Mount Vernon commemorating the birthday of George Washington, and reaffirmed owning slaves was the right of any American citizen. Two camps of the Republican party had emerged in Congress, War Republicans, being those that believed, though slavery was inhumane, secession was an act of treason and deserved to be treated as such, and the Seditious Front, named such for their defense of New England's secession. The War Republicans were led by a mixed motley of senators and governors from Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, though the most prominent of which was Edgar Cowan, a slavery-neutral Republican senator from Pennsylvania, who had a reputation for crossing the floor. Upon learning of the secession, on the morning of January 7, Cowan was the first of War Republicans to issue a condemnation, and in his statement said that "[he] [knows] that a peaceful and democratic resolution can solve the issue of slavery," and that "the formation of a new nation, made from blood, will only make matters worse."

He then informally formed the faction with New Jersey senator Alexander G. Cattell, Wisconsin House Representative Walter D. McIndoe, California House Representative Donald C. McRuer, and Coloradan non-voting delegate, Hiram Pitt Bennet. House Representative Oakes Ames, who did not sign the declaration, was appointed the universal representative for the state of Massachusetts as long as it was 'occupied,' and he too quickly became an advocate of the War Republican stance, though was viewed with relative suspicion. However, in an odd turn of events, Republican governor of Michigan, Henry H. Crapo became the strongest defender of the New England status of independence, stating in an unpopular speech that "all peoples have a right to self-determination, and when a political dynasty that opposes that people's ideals takes power, with no sign of deescalating in power or oppression inflicted, they then have the right to secede from that government.'

The name for the faction came from a rebuttal by Toombs' Secretary of State, James M. Mason, which referred to the group as "nothing but a front for seditious traitors," which they then co-opted. Despite taking up only twenty-eight of the 193 seats in the House of Representatives, and only nine senators of the seventy-two seats in the Senate, they were a vocal minority, and were often the subjects of passionate speeches and demands for arrest. Furthermore, the last known pistol duel in the United States was held between Missouri Democratic senator Waldo P. Johnson and Michigan Republican senator Zachariah Chandler. Johnson was subsequently shot in the left cheek, and died of his injuries, while a Michigan court refused to convict Chandler for murder. This state of affairs continued until late March, when Toombs released The Ordway Memorandum, a document compiled by Nehemiah G. Ordway, which was the basis for an executive order which expelled all government officials with 'insurgent affiliation,' which then allowed the Democratic Party full control over all branches of governance, effectively ending the Seditious Front, and forcing all other Republican officials to run as Democrats, or as independents.

By early March, the war had seemingly stalemated as the Union troops on the Vermont-New York border remained without orders, and the other fronts had still been struggling to mobilize. Toombs gave an order for 15,000 men, though as the military hadn't faced a major conflict since 1815, they were wholly unprepared, and corruption had plagued the military since Hamilton's conquest of Spanish Florida in 1799. The mobilization procedure was planned to take a week, but had lasted without substantial progress since the order was issued in late February. The Union troops had begun getting anxious, taking casualties each day from guerrillas, and their commanding officer, General George Stoneman believed that a small morale victory was necessary to sustain the front where it was. Thus, defying direct orders of inaction, he led a force of 400 men into a pocket in southern Vermont, finding themselves in the forest surrounding Whipstock Hill, vastly underestimating the newly found strength of the army. New Englander troops hid in the forest had surrounded them using cavalry and small, constantly moving units, while the Union soldiers had no idea where to fire. The dark green uniforms used in the attack blended in with the surrounding area, making things continually more difficult for Union troops.

Seeing no other way of surviving than to force the enemy into a pitched battle, Stoneman ordered a small suicidal cavalry charge as a diversionary attack, breaking the encirclement, while the remaining soldiers retreated to a dry stone wall and begun digging trenches, though they failed to be very effective. The Union troops held the hill for seven hours, until 2:00 in the following morning, when the exhausted remaining force of two-hundred men surrendered, including Stoneman, who had been the only experienced general on the front. The soldiers, not knowing what to do with the prisoners of war, marched them through Bennington at bayonet-point, where they were humiliated. Water was splashed on them, insults hurled, and at one point, cow excrement was slung at them. Later that afternoon, runners reported orders from Joseph Hooker to construct fortifications, a fallback line, and for all prisoners of war to be kept at a camp a minimum of seven and a half miles from the front line, which would become the forward operating base. A transcript of the order further reveals that the troops were instructed to fight a pitched battle if necessary, and that hit-and-run tactics could only succeed for so long.

It was around this time that the Secretary Higginson had declared the process of impressment of ships into the Honorable Navy of the Serene Republic concluded. By this time, an estimated 85% of ships laid down in Charlestown Navy Yard had been repossessed for the purposes of the Navy, and the British delegation had agreed to lend them the HMS Donegal, HMS Cossack, and HMS Griffon, and after some negotiation, one of four ironclad warships owned by the Royal Navy, the HMS Warrior. This gave them a clear advantage, as the United States Navy had lacked funding, as for a considerable time, it was believed that the largest threat was posed by a Canadian invasion, where the largest strength would come from the land forces, and there was no foreseeable chance for them to pose a threat to the Royal Navy. Thus, there was only 32 commissioned ships in the Union Navy when the Charlestown Navy Yard had been commandeered, and shipbuilding and whaling had been some of the most lucrative industries in New England, and though the Navy of the Serene Republic was formed without central command and without preparation, they had an significant combat advantage of the Union Navy. It was around this time that Gideon Welles and James Alden Jr. were appointed by Secretary Higginson to be appointed to be the chief admiral and vice admiral respectively, of the Navy.

As a common form of favor-seeking, Toombs had appointed a close-friend and inexperienced soldier, Henry L. Benning, to the position of Secretary of the Navy, as it was believed that the position didn't hold any true merit or governing power in modern American society, but when the Civil War had begun, the issues with such an appointment had become glaringly obvious, though Toombs believed a sudden dismissal would worsen the already deteriorating morale of the cabinet, and appointed David Farragut as the Under Secretary, hoping that Farragut would give orders upon Benning's behalf, and tutor him in naval combat, though Benning was known for his pride, and this never occurred. Farragut was appointed as Naval Secretary on December 20, 1868, but by them the damage had, in most part, already been done.

The first naval battle of the war was March 2, at Norwalk Bay. A division of steam gunboats led by Donald McNeill Fairfax, hoping to gain accolades for an unordered blow against the New Englanders, moved north from Smithtown bay on Long Island. Coincidentally, on the southern bay, sailors of the Honorable Navy were being trained on how to use the HMS Warrior. Upon noticing the gunboats, flying the American flag, the British naval architect and designer Thomas Lloyd, ordered the crewmen to try to intercept the ships. Lloyd had been gravely seasick and apparently manic. A sailor on the Warrior, Edward Papen, wrote the following in his memoir.

"It seemed the crew had been too terrified of drowning, and too terrified of a whisky-drunk Lloyd to say no. We had no particular idea of how to work much of anything, not the guns, nor would we likely have known how to steer if Lloyd had been thrown overboard. Upon being assigned our task, that was, to the Warrior, we'd only heard vaguely whispered talkings [sic] of Lloyd's reputation, and it was surely nothing alike that of the man that we saw. We were told he was cultured, British, and did not have a taste for American indignity. But, how ever it was, dignified or not, British or not, he certainly had a taste for American bourbon, and such was only made worse once he was thrust into the position of naval officer. But he took some glee in his power, to see his inventions put to work, but I was fairly sure then that we were being ordered into death. Little did I know, we would emerge with no casualties, with the ship practically unscathed."

Initially, Fairfax did not know what to make of the vessel, unsure of what it was, or if it was a vessel at all, and got at dangerous closeness with it, while the crew of the Warrior fumbled for the guns. It wasn't until Lloyd's yelling from the inside of the vessel was heard did Fairfax figure that it was a ship, and asked them to identify themselves or be fired upon. The Warrior replied with a salvo of twenty of it's guns, sinking two of the four ships within two minutes. Fairfax's ships attempted to fight back, but the cannons left little but dents on the armor. Witnessing this, Fairfax gave out a order to retreat back to Long Island, but the final two ships were fired at and then rammed, destroying them beyond repair, and concluding the battle with a catastrophic loss for the Union, while what was meant to be a simple training exercise became an almost folklore, and grand propaganda victory.

Similar efforts occurred as status-appointed naval officers sent gunboats and small armed yachts, wishing to win themselves glory against the Honorable Navy, who they presumed based off of the publication of the Battle of Albany, was entirely incompetent, only to themselves be defeated. Similar events occurred at the Battle of Block Island Sound, the Battle of Buzzard's Bay, the Raid at Shea Island, and the Battle of Jennings Beach, all of which culminated in a New Englander victory, and with the total destruction of the Union naval force involved. This led subsequently to Secretary Benning giving the order to all naval commands to stand down and to only fire if fired upon, while they organized what would become the Carver Campaign. By March 22, 20,000 men were assigned to the New York-Connecticut and New York-Massachusetts border, with fortifications built as to prepare for the coming offensive.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).