User:Jxs2643/Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin | |

|---|---|

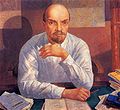

Self-Portrait, 1929 | |

| Born | Kuzma Sergeyevich Petrov-Vodkin November 5, 1878 |

| Died | February 15, 1939 |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Known for | Painting, literature |

| Notable work | Bathing of a Red Horse (1912), Fantasy (1925) |

| Movement | Russian avant-garde, Socialist Realism |

| Spouse | Maria Feodorovna (1885–1960) |

Kuzma Sergeyevich Petrov-Vodkin (b. November 5, 1878) was a Russian icon painter who produced Russian avant-garde and Socialist Realism artwork throughout Russian and Soviet Union history in the early twentieth century. [1] Petrov-Vodkin specialized in icon painting, and his work was rooted in both his nation and personal artistic style, which included his use of symbolism, cubism, and spherical perspective.[1] Like many artists of the Russian avant-garde in the early 20th century, he was attracted to experimentation with cubism, constructivism, and perspective prior to the dawn of Socialist Realism in 1932, during which he still maintained a level of artistic integrity as he produced artistic propaganda for the glory of the state.[2] He was not an active political figure, but he did support the socialist revolution and was appointed head of the Leningrad Union of Artists in 1933. [3] Petrov-Vodkin developed an artistic technique known as spherical perspective in which the objects and landscape of the painting are depicted from a higher vantage point, which provides a unique use of three-dimensional space and a spherical view of the landscape, as well as increased room for metaphorical expression and interpretation in his paintings.[3]

Biography

[edit]Early Years and Education

[edit]Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin was born in the small provincial town Khvalynsk in the Saratov region on the Volga River.[2] As his father was a poor cobbler, Petrov-Vodkin was born into an impoverished family and as a result he endured a childhood full of hardships.[1] When he was two years old, his father was called to serve in Saint Petersburg, and as a result he and his family reallocated to the Russian empire's capital where they remained for the following two and a half years.[2] Petrov-Vodkin demonstrated an active interest in art from an early age, and his artistic talent and ambition to become an artist enabled him to overcome his class background. In 1894 and 1895, Petrov-Vodkin enrolled and studied technical drawing and painting at the classes of Burov and Samara, and from 1895 to 1897 he studied at the Baron Stieglitz' Central School of Technical Drawing in St. Petersburg.[4] Afterward he moved to Moscow where he enrolled in the new Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture in 1897 and studied under prominent Russian artists such as Arkhipov, Kasatkin, and Valentin Serov.[4] In 1901, he studied at the Azbe studio in Munich, Germany, and from 1905 to 1908 he studied at private Academies in Paris, which included the prestigious Colarossi's studio.[4]

Career

[edit]During World War I, Petrov-Vodkin was enlisted into military service under the Russian Empire, and he was assigned to the Saint George Cavaliers of the Izmailovsky regiment in 1916 where he was provided with a private apartment and his duties consisted of painting portraits of the officers of his regiment.[2] Petrov-Vodkin detailed his experiences from the regiment in a letter sent home to his mother, which contrasted those of his father's, who was a mere cobbler but like his son also served under "His Majesty's regiments," as Petrov-Vodkin wrote.[2]

Petrov-Vodkin began exhibiting his work in 1908, and his work was displayed in a number of exhibitions which included The Golden Fleece in the 1900s, the Union of Russian Artists in 1909 and 1910, Jar-Tsvet in 1924, and the AKhRR in 1928.[4] Prior to the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Petrov-Vodkin had not previously aligned himself with any artists' faction, but from 1910 until 1922 he exhibited his work with the World of Art group.[2] In addition to his long-term membership in the World of Art group, Petrov-Vodkin also formed part of the Union of Artists at the House of the Art in 1920 and 1921 and the Four Arts from 1925 to 1928.[4]

Personal Life

[edit]In 1906, at twenty-eight years old, Petrov-Vodkin married Maria Jovanovic (Maria Fyodorovna in Russian), the daughter of the Serbian immigrants and the owners of the house he was staying at located just outside Paris.[3] In 1907, Petrov-Vodkin painted his wife's portrait in which he incorporated a color palette consisting of dark blues, greens, and black.[3]

In addition to painting, Petrov-Vodkin worked as a teacher for extended periods at a time during his life, as he was passionate about teaching aspiring artists and the new generation of Soviet artists his personal techniques and methods as an icon painter.[3] Beginning in 1910 he worked at the Zvantseva School in St. Petersburg, and he later taught at the Free Studios in Petrograd as well as the Academy of Fine Art from 1918 to 1932.[3][4] Petrov-Vodkin enjoyed teaching greatly, and his years as a teacher had a lasting impact on his students. One of his former students, Leonid Chupiatov, became inclined to the theory of spherical perspective reminiscent of a "fish-eye lens" that was taught to him by Petrov-Vodkin.[5] In Chupiatov's painting, Armored Train 14,69, spherical perspective can be noted as a method of rotating the scene on a circular stage.[6]

Petrov-Vodkin was also an avid traveler, and he travelled to several different countries and continents throughout his lifetime.[4] In 1905 he travelled to Turkey and Italy; in 1921 he travelled to Warsaw, Prague, Leipzig, and Munich; and for working trips and artistic purposes, he travelled to North Africa, Central Asia, and Paris.[4] Petrov-Vodkin deeply cherished his trip to North Africa in 1907, which seemed to produce a lasting impact on the style and color implemented in his paintings.[3] In a letter sent home to his family, he wrote:

"I was right to consider that after European civilization which I know so well it was necessary for me to examine thoroughly a different life. And now I see that there are many ignorant people in our own culture; that there are lies everywhere and that we are far from the truths of life. Much of what I loved before I now despise..."[7][3]

Petrov-Vodkin was also passionate about literature and produced several autobiographical works.[8]

Works

[edit]Artistic Style & Techniques

[edit]

In the years of the early twentieth century leading up to the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin gained recognition as one the great Russian modernist painters of his time through his highly original fusion of symbolism and traditional forms of Russian and Italian Renaissance art.[8] Petrov-Vodkin's admiration for medieval Russian and Italian Renaissance techniques influenced the icon paintings and still-lifes he produced over the course of his lifetime.[8]

Unlike many other Russian avant-garde artists, Petrov-Vodkin did not abandon objective abstractions in the years following the Revolution as Socialist Realism was on the rise.[2] He maintained his artistic integrity over time and continued with the principle of traditional icon painting in the years after the Revolution and throughout the early 1920s.[2] As he matured as an artist over time and experimented with new methods of spatiality and color, Petrov-Vodkin developed his theory of 'spherical perspective' in the late 1910s.[9] 'Spherical perspective' entailed manipulating space and transforming the painting's traditional linear axis into a spherical one, which allowed him to alter three-dimensional space in a new way.[5] Spherical perspective has been compared to the "fish-eye lens" incorporated in film, and the theory is synonymous with Petrov-Vodkin's status as a great modernist painter.[1] Petrov-Vodkin combined his newfound theory of 'spherical perspective' with a tricolor palette consisting of red, yellow, and blue (primary colors), and he explored this combination in paintings such as In the Line of Fire (1915-16), By Lenin's Coffin (1924), and Death of a Commissar (1928).[2] Petrov-Vodkin's unique ability to implement both traditional elements of Renaissance art as well as new techniques, such as spherical perspective, allowed him to transition smoothly into the years of Socialist Realism, which aimed to produce realistic art that did not rely on symbolism in order to ensure that the art (and propaganda) was easily understood by the public.[8]

Pre-Revolutionary Art

[edit]In 1917, Petrov-Vodkin's largest painting yet, In the Line of Fire, was exhibited at the Mir iskusstva (World of Society) exhibition.[2] Unlike many of the works he completed around the same time, In the Line of Fire was not commissioned by any exhibition or private entity and was instead a personal labor that Petrov-Vodkin was impelled to create.[2] When Petrov-Vodkin began the 196 x 275 cm easel painting in 1915, Russia was a nation captivated by patriotism and the belief that the outbreak of World War I was an opportunity for Russia to claim its rightful place on the global stage as a major European power.[2] By the time he completed the painting in 1916, the transitory patriotic enthusiasm had begun to fade, and when it was displayed at the Mir iskusstva exhibition a year later, political turmoil had taken the Russian Empire by storm in the aftermath of the February Revolution of the same year, 1917.[2]

Depicted in the painting is a wounded ensign leading his Russian platoon in a bayonet attack up a hillside.[2] Petrov-Vodkin portrays the platoon, which is comprised of seemingly uniform Russian soldiers, at different lengths upon the hillside as they charge up the hill in attack.[10] The soldiers appear as though they are charging straight toward the viewer of the painting, and their staggered positions on the canvas build up toward the central figure of the painting, the wounded ensign, whose eyes align with both the horizon and the viewer.[2][10] The painting's profundity stems from the simultaneously ambiguous and "striking" expression on the mortally wounded ensign's face, which could be interpreted as one of pain or resignation.[2]

Contrary to many of his previous paintings which incorporated significant allegorical and metaphorical elements, In the Line of Fire is rooted more deeply in a realistic, traditional portrayal of the battlefield.[2] The amount of preparation and sketches that went into the painting suggest that Petrov-Vodkin was determined to create an enduring depiction of battle: ten drawings focused on the poses and gestures of the soldiers surrounding the wounded ensign at the center, and sixty-six studies that dealt solely with the wounded ensign as the central figure of the painting were prepared prior to the final painting.[2] A number of these drawings later indicated that the pose, figure, and overall complexion of the wounded ensign were modeled by Petrov-Vodkin's cousin, who also served as the model for the man mounted on the horse in Bathing of a Red Horse (1912).[2]

Post-Revolutionary Art

[edit]Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin was one of just a few Soviet artists selected and permitted to sketch the Soviet Union's fallen leader, Vladimir Lenin, in his coffin at his funeral service in 1924. By Lenin's Coffin was completed on canvas in 1924, and in it a lifeless Lenin is depicted resting in his coffin with a saint-like radiance, resembling a god or holy figure.[11] In the aftermath of Lenin's death, the phrase "Lenin is alive" began to circulate, which effectively solidified the belief in the Soviet Union that Lenin was not dead; he was simply resting before his deity-like resurrection. Artistic evidence of Lenin's mortality, such as Petrov-Vodkin's By Lenin's Coffin, threatened Lenin's sacred image in the Union, and as a result the painting was hidden from the public eye and has largely remained in storage of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow ever since.[12] Spherical perspective plays a crucial role in By Lenin’s Coffin because it exaggerates the spherical nature of the landscape by zooming in on the central object oft he painting (Lenin lying in his coffin) from a higher viewpoint while simultaneously zooming out from the background (the commoners in the crowds gathered around Lenin’s coffin).

Renowned Works

[edit]

In the aftermath of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the Russian avant-garde that dominated much of early twentieth century Russian art began to wane as the nascent Soviet Union developed in the early to mid 1920s.[13] While some artists maintained their former style, many artists strayed from easel painting in favor of more constructive and social utilitarian art.[13] The October Revolution was such a momentous occurrence in Russian culture that it was viewed by many as a "cosmic event," and the artists of the avant-garde expressed this interpretation through their paintings as well.[13] Prior to other Russian modernists and several years before the Revolution, Petrov-Vodkin had already begun experimenting with different perspectives and methods of skewing the planetary, spherical nature of the earth, which marked the commencement of his development of spherical perspective.[13] In Petrov-Vodkin's 1925 painting, Fantasy, the rider mounted on the vibrant red horse is depicted as bounding into the "deep blue cosmos" of the countryside, which Petrov-Vodkin depicted using a primarily blue color palette as well as hues of green.[13]

Petrov-Vodkin revived the image of the red horse from his widely recognized Bathing of a Red Horse (1912) in Fantasy. Bathing of the Red Horse was exhibited to the public for the first time at the World of Art group exhibition in 1912, and while some deemed it too erotic, many praised it and as a result it gained instantaneous fame and recognition. Onlookers, including his peers, viewed it as a "presaging of a future cataclysm and renewal of the world."[1] In Fantasy, on the other hand, a peasant donned in simple clothes and no shoes is portrayed mounted on the vibrant red stallion leaping atop the mountains and into the countryside depicted below. [3] While the red horse in Bathing of a Red Horse (1912) was subsequently interpreted as a prediction, or foreshadowing, of the imminent 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the red horse in Fantasy (1925) was representative of the passionate revolutionary spirit of the nascent Soviet Union in the years after the revolution.[3] As the red horse leaps confidently toward the open countryside below, the peasant is depicted looking back toward what lies behind.[6] The heavy symbolism Petrov-Vodkin incorporated in Fantasy and other works waned once Socialist Realism was established in 1932, which mandated the production of artwork that both glorified the state and depicted the proletariat's journey toward a socialist future in a realistic, accessible way.[3]

Later Years and Legacy

[edit]

Petrov-Vodkin's works were displayed in the Soviet Union's final exhibition of 1929, the Exhibition of Works on Revolutionary and Soviet Themes, which aimed to bridge the gap between the avant-garde of pre-Revolutionary art and the realism of contemporary Soviet art.[14] Compared to the other artists of the exhibition which included Boris Kustodiev and Konstantin Savitsky, Petrov-Vodkin was "by far the most overtly political painter represented in the first hall of the exhibition."[14] His works were of value to the exhibition as they implemented the avant-garde elements of Revolutionary art while simultaneously incorporating the realism of the modern Soviet style, which evoked the sense of a continuous progression from Revolutionary art to contemporary art.[14]

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin died in 1939 in Leningrad at the age of sixty-one. Despite his reputation as a great pre-Revolutionary and Soviet artist in the years leading up to his death, Petrov-Vodkin's name was rapidly forgotten in the following years, and he remained forgotten for much of the remainder of the Soviet Union.[9] In the 1960s, Petrov-Vodkin and his artistic work from the Russian Empire and Soviet years were rediscovered.[9] In 2017, the Royal Academy of Arts in London hosted an exhibition marking the centenary of the Russian Revolution, and several of Petrov-Vodkin's works, including By Lenin's Coffin (1924), Fantasy (1925), and Still Life with a Herring (1918), were displayed.[11]

Artwork

[edit]-

Self-Portrait, 1918

-

Bathing of a Red Horse, 1912

-

Thirsty Warrior

-

Portrait of Anna Akhmatova, 1922

-

Fantasy, 1925

-

The Mother of God of Tenderness Towards Evil Hearts

-

Portrait of the Artist's Daughter, 1935

-

Shore, 1908

-

Petrograd Madonna, 1918

-

Portrait of the Artist's Mother

-

Girls on the Volga, 1915

-

Death of a Commissar

-

Lenin

-

Boys Playing

-

Labourers, 1926

-

Sleep

-

After the Battle, 1923

-

Fisherman's Daughter

-

Motherhood

-

The Worker

-

Bather's Morning

Bibliography

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Sarabianov, Andrei D. (July 2, 2020). "Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin". Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Hutchison, Margaret; Trout, Steven (2020). Portraits of Remembrance: Painting, Memory, and the First World War. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-2050-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Machmut-Jhashi, Tamara. The Art of Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (1878-1939). United States, Indiana University, UMI Company, June 1995

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kovtun, Evgueny (2010). "Russian Avant-Garde". ProQuest Ebook Central.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b LEVIN, ILYA. “Armored Train 14,69: A One-Way Trip to Socialist Realism.” Russian History, vol. 8, no. 1/2, 1981, pp. 233–241. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24652396. Accessed 23 Nov. 2020.

- ^ a b Uglow, Jenny (March 8, 2017). "When Art Meets Power". The New York Review.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Letter dated 27 May 1907, in Selizarova, p. 102

- ^ a b c d e Chilvers, Glaves-Smith, Ian, John (2015). "A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art". Oxford Reference.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c "Artist Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin". Russian Life. vol. 46, no. 46: p.16. November–December 2003 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b Anchukov, Sergey Vasilievich (September 7, 2020). "Conveying the Perspective Reductions in Human Height on a Flat Surface and Platforms of Different Levels on the Flat Picture Plane of a Painting". Atlantis Press.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Sixsmith, Martin (December 20, 2016). "The Story of Art in the Russian Revolution". Royal Academy of Arts.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Macpherson, Amy (January 20, 2017). "The Russian painting that's so controversial it's in storage". Royal Academy.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e Douglas, Charlotte (January 1, 1975). "The Universe: Inside and Out, New Translations of Matyushin and Filonov". ProQuest.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Byers, Mary Hannah. The Rise of Socialist Realism in the Exhibitions of the State Tret'iakov Gallery 1924-1934. Faculty of Social Sciences University of Glasgow, ProQuest LLC(2018), June 2004.