User:Joshua Jonathan/Mauryan Empire

| This is a user-space draft, to collect sources. |

"Extravagant ideas have been put forward as to what Seleucus did cede."[1]

Seleucus

[edit]According to the Roman historian Appian, History of Rome, Seleucus was

Always lying in wait for the neighboring nations, strong in arms and persuasive in council, he acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapouria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by Alexander, as far as the river Indus, so that the boundaries of his empire were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander. The whole region from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus.[2]

Assasination of Greek eastern Indus Valley governors(c. 316 BCE)

[edit]The Roman historian Justin described how Sandrocottus (Greek version of Chandragupta's name) assasinated Greek governors[3] and took over power in the northwest:

"India, after the death of Alexander, had assassinated his prefects, as if shaking the burden of servitude. The author of this liberation was Sandracottos [Chandragupta], but he had transformed liberation in servitude after victory, since, after taking the throne, he himself oppressed the very people he has liberated from foreign domination."

— Junianus Justinus, Histoires Philippiques Liber, XV.4.12-13 [4]

Boesche, referring to Radha Kumud Mookerji, Chandragupta Maurya and His Times, 4th ed. (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1988 [1966]), 31, 28-33:

Just after Alexander's death in 323 B.C.E., Chandragupta and Kautilya began their conquest of India by stopping the Greek invaders. In this effort they assassinated two Greek governors, Nicanor and Philip, a strategy to keep in mind when I later examine Kautilya's approval of [End Page 10] assassination. "The assassinations of the Greek governors," wrote Radha Kumud Mookerji, "are not to be looked upon as mere accidents."[3]

Seleucus crosses the Indus (c. 305-303 BCE)

[edit]According to Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars,

[Seleucus] crossed the Indus and waged war with Sandrocottus [Maurya], king of the Indians, who dwelt on the banks of that stream, until they came to an understanding with each other and contracted a marriage relationship. Some of these exploits were performed before the death of Antigonus and some afterward.[2]

Alliance

[edit]The alliance is briefly mentioned by, or alluded to, by Greco-Roman authors Strabo (64 or 63 BCE – c. 24 CE) XV 2,9,[5][6] Plutarch (1st c. CE),[7] Justin (2nd c. CE),[8] and Appian (2nd c. CE) 'Syr. 55.[5][6]

According to Jansari, Strabos and Plutarch may have drawn information from the same source, possibly Megasthenes.[7] No Indian sources record the events,[9] and Jansari warns that "the dependence on a small group of sources from only one literary tradition necessitates a cautious approach to these texts and the events they describe."[10] Jansari further notes that "None of the ancient authors depicted either Seleucus or Chandragupta as the clear victor of this battle."[11]

Overview of the alliance

[edit]Strabo mentions the exchange of elephants and territory as part of the dynastic marriage-alliance.[7] In his Geographica, composed about 300 years after Chandragupta's death, he describes a number of tribes living along the Indus, and then states that "The Indians occupy [in part] some of the countries situated along the Indus, which formerly belonged to the Persians."[12] Geography, XV, 2.9:

The geographical position of the tribes is as follows: along the Indus are the Paropamisadae, above whom lies the Paropamisus Mountains: then, towards the south, the Arachoti: then next, towards the south, the Gedroseni, with the other tribes that occupy the seaboard; and the Indus lies, latitudinally, alongside all these places; and of these places, in part, some that lie along the Indus are held by Indians, although they formerly belonged to the Persians. Alexander [III 'the Great' of Macedon] took these away from the Arians and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus [Chandragupta], upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange five hundred elephants.[13]

Jansari notes that "them," in Strabo, refers to "territories previously held by Alexander, but it is not scpecified which these were."[7]

According to Jansari, in the 20th century diverging views on Chandragupta have developed between western academics and Indian scholars.[14] While westerners tend to take a reserved view on Chandragupta's accomplishments, Indian authors have portrayed Chandragupta as a very succesfull king who established the first Indian nation.[14]

V.A. Smith (1914), p.149:

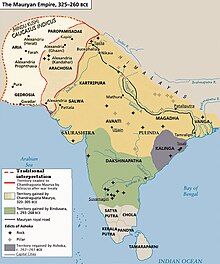

the cession made in 3O3 b.c. by Seleukos Nikator to Chandragupta Maurya included provinces of the Paropanisadae (Kabul), Aria (Herat), Arachosia (Kandahar), and probably Gedrosia (Makran), or a large part of that satrapy.

Tarn (1922), The Greeks in Bactria and India, p.100, explicitly criticises V.A. Smith (The Early History of India, appendix F, .149 (3rd edition):

Extravagant ideas have been put forward as to what Seleucus did cede [...] The worst has been that of V. A. Smith, who gave Chandragupta the satrapies of Gedrosia, Arachosia, Paropamisadae, and Aria on the strength of Pliny VI, 69, a historical absurdity of unknown origin.

Tarn, writing in 1922 before the discovery of the edicts of Ashoka in Kandahar and Laghman Province in the 1950s-60s, limits the exchanged territory to the Indus Valley. According to Tarn, the imit followed the Kunar river, east of Kabul and ending in Jalalabad,[a] further south along the watershed, and ending at the Hingol river:[1]

The Paropamisadae was not among the provinces ceded by Seleucus to Chandragupta. Extravagant views have been put forward as to what Seleucus did cede, but there is a passage from Eratosthenes, usually neglected, which seems plain enough. It says that, before Alexander, the Paropamisadae, Arachosia, and Gedrosia all stretched to the Indus; the reference is to the Achaemenid satrapies, and it implies that in Persian times the Paropamisadae and Gandhara were one satrapy. Alexander (it continues) took away from Iran the parts of these three satrapies which lay along the Indus and made of them separate [caroikia] (which must here mean governments or provinces); it was these which Seleucus ceded, being districts predominantly Indian in blood. In Gedrosia the boundary is known; the country ceded was that between the Median Hydaspes (probably the Purali) and the Indus, as is shown by a later mention of the Hydaspes 4 as the boundary of Iran in this direction. Of the satrapy which Eratosthenes calls Paropamisadae Chandragupta got Gandhara, the land between the Kunar river and the Indus; this is certain, because Eratosthenes says that he did not get the whole, while the thorough evangelisation of Gandhara by Asoka shows that it belonged to the Mauryas. The boundary in Arachosia cannot be precisely defined; but, speaking very roughly, what Chandragupta got lay east of a line starting from the Kunar river and following the watershed to somewhere near Quetta and then going to the sea by Kalat and the Purali river; that will serve as an indication. The Paropamisadae itself was never Chandragupta’s.[1]

According to Thapar (1963), referring to Smith (1914), History of India,

"Certain areas in the north-west were acquired through the treaty with Seleucus. There is no absolute certainty as to which these areas were and it has been suggested[b] that the territory ceded consisted of Gedrosia, Arachosia, Aria [modern-day Herat], and the Paropamisadae."[15]

Mookerji, Radhakumud (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass Publisher. ISBN 978-81-208-0405-0:

By the terms of the treaty, Seleukos ceded to Chandragupta the Satrapies of Arachosia' (Kandahar) and the Paropanisadae (Kabul), together with portions of Aria (Herat) and Gedrosia (Baluchistan). Thus Chandragupta was able to add another glorious feather to his cap. He extended his empire beyond the frontiers of India up to the borders of Persia. That is why it was possible for his grandson Asoka to declare in two of his Rock Edicts^ [11 and XIII] that the Syrian emperor, Antiochus [Amiyaho Yona^raja]^ was his ‘"immediate” neighbour, one of his ""frontagers” (an Anta or a Pratyanta king). "

Boesche (2003)

By taking much of western India (the Punjab and the Sindh) from the Greeks and concluding a treaty with Seleucus (Alexander the Great's Greek heir to western India), Chandragupta and Kautilya succeeded in bringing together almost all of the Indian subcontinent.[3]

Kosmin summarizes those sources as follows, cautiously interpreting which territories may have been transferred:

The ancient historians Justin, Appian, and Strabo preserve the three main terms of what I will call the Treaty of the Indus:

(i) Seleucus transferred to Chandragupta's kingdom the easternmost satrapies of his empire, certainly Gandhara, Parapamisadae, and the eastern parts of Gedrosia, and possibly also Arachosia and Aria as far as Herat.

(ii) Chandragupta gave Seleucus 500 Indian war elephants.

(iii) The two kings were joined by some kind of marriage alliance (ἐπιγαμία οι κῆδος); most likely Chandragupta wed a female relative of Seleucus.[8]

Gedrosia (Baluchistan)

[edit]Malan mountain range (Purali/Hingol river)

[edit]

V.A. Smith (1914), Early History of India,[16]:

The satrapy of Gedrosia (or Gadrosia) extended far to the west, and probably only the eastern part of it was annexed by Chandragupta. The Malin range of mountains,[c] which Alexander experienced such difficulty in crossing, would have furnished a natural boundary.

Pierre Eggermont describes the area, stating that the Malan range is an offshoot of the Makran Coastal Range, which was explored by Sir Aurel Stein, who found out that "the Buzelak, or "Goat's Pass", leading from the Malan plain across the Malan range into the plain of Ormara proved to be very steep," concluding that it was unlikely that Alexander had passed over the Malan range.[17]

Lewis Vance Cummings also gives a description of the struggles of Alexander's army at hteir retreat from India:

They turned west, reaching the mouth of the Tomerus (Hingol) River [...] Alexander, true to his tactical principles, prepared to advance along the coast [...] An unexpected obstacle arose to the continuance of the line of march. On the other side of the river loomed the utterly impossible barrier of the Malan (modern name) mountain range, its seaward end dropping abruptly and precipitately into the ater, and barring passage.[18]

Tarn refers to Eratosthenes, who states (in Tarn words) that

Alexander [...] took away from Iran the parts of these three satrapies which lay along the Indus and made of them separate [...] governments or province; it was these which Seleucus ceded, being districts predominantly Indian in blood. In Gedrosia the boundary is known: the country ceded was that between the Median Hydaspes[d] (probably the Purali[e]) and the Indus."[1]

With regard to Gedrosia, more recent authors mention either "Gedrosia," implying that the whole of Gedrosia was ceded to Chandragupta, without giving a rationale; or the more modest '[the eastern] part of Gedrosia'.

With regard to Gedrosia, more recent authors mention either "Gedrosia," which gives the impression that Baluchistan as far as Iran was hand over, or '[the eastern] part of Gedrosia'. According to Thapar (1963), referring to Smith (1914), History of India,

"Certain areas in the north-west were acquired through the treaty with Seleucus. There is no absolute certainty as to which these areas were and it has been suggested[b] that the territory ceded consisted of Gedrosia, Arachosia, Aria [modern-day Herat], and the Paropamisadae."[15]

According to Thapar (1963), referring to Smith (1914), History of India,

"Certain areas in the north-west were acquired through the treaty with Seleucus. There is no absolute certainty as to which these areas were and it has been suggested[b] that the territory ceded consisted of Gedrosia, Arachosia, Aria [modern-day Herat], and the Paropamisadae."[15]

According to Grant, Seleucus Nicator ceded the Hindu Kush, Punjab and parts of Afghanistan to Chandragupta Maurya.[22] According to Kosmin, Seleucus "certainly" transferred "the eastern parts of Gedrosia."[8]

Lower Indus Valley

[edit]Coningham & Young also question the extent of control over the lower Indus Valley, following Thapar, noting that this may hve been an area of peripheral control.[23]

Raymond Allchin also notes the absence of major cities in the lower Indus valley.[24]

Malcolm Robert Haig (1894):

...the general rising of the northern peoples headed by Chandragupta, the founder of the Maurya dynasty of Pataliputra, followed in rapid succession. The Lower Indus Valley now became free from foreign rule, and the local chiefs were no doubt left to their own devices. Nominally the territory may have been a dependency of the Mauryan kingdom, but, separated from the main body of that kingdom by a wide expanse of desert, and at a vast distance from the capital on the Ganges, its tie of allegiance must have been of the slightest. This independence, or semi-independence, lasted under no doubt varying degrees of definiteness […] till […] Demetrius, in the second century B.C., invaded Patalene in force and completely subjected it to Bactria.[25]

Paropamisadae (Gandhara and Kabul) and Arachosia (Kandahar)

[edit]Tarn, writing in 1922 before the discovery of the edicts of Ashoka in Kandahar and Laghman Province in the 1950s-60s, limits the exchanged territory to the Indus Valley. According to Tarn, the imit followed the Kunar river, east of Kabul and ending in Jalalabad,[g] further south along the watershed, and ending at the Hingol river:[1]

The Paropamisadae was not among the provinces ceded by Seleucus to Chandragupta [...] there is a passage from Eratosthenes, usually neglected, which seems plain enough. It says that, before Alexander, the Paropamisadae, Arachosia, and Gedrosia all stretched to the Indus; the reference is to the Achaemenid satrapies, and it implies that in Persian times the Paropamisadae and Gandhara were one satrapy. Alexander (it continues) took away from Iran the parts of these three satrapies which lay along the Indus and made of them separate [caroikia] (which must here mean governments or provinces); it was these which Seleucus ceded, being districts predominantly Indian in blood [...] Of the satrapy which Eratosthenes calls Paropamisadae Chandragupta got Gandhara, the land between the Kunar river and the Indus; this is certain, because Eratosthenes says that he did not get the whole, while the thorough evangelisation of Gandhara by Asoka shows that it belonged to the Mauryas. The boundary in Arachosia cannot be precisely defined; but, speaking very roughly, what Chandragupta got lay east of a line starting from the Kunar river and following the watershed to somewhere near Quetta and then going to the sea by Kalat and the Purali[h] river; that will serve as an indication. The Paropamisadae itself was never Chandragupta’s.[1]

Kosmin writes that Seleucud "certainly" ceded Gandhara and Parapamisadae (this includes Gandhara), but "possibly" also Arachosia.[8]

Aria (Herat)

[edit]

The acquisition of Aria (modern Herat) is disputed. Smith included a large part of Aria, referring to Strabo, Appian, Plutarch, Justin and Pliny.[26]

Stabo XV, 1, 10:

the Indus River was the boundary between India and Ariana, which latter was situated next to India on the west and was in the possession of the Persians at that time; for later the Indians also held much of Ariana, having received it from the Macedonians.[27]

Pliny the Elder (23/24–79 CE):

Most geographers, in fact, do not look upon India as bounded by the river Indus, but add to it the four satrapies of the Gedrosia, the Arachotë, the Aria, and the Paropamisadë, the River Cophes [Kabul River], thus forming the extreme boundary of India. According to other writers, however, all these territories, are reckoned as belonging to the country of the Aria.[28]

Smith reads Strabo XV 1,10 as implying that "Strabo informs us that the cession included a large part of Ariane."[26] He further argues that Pliny, in his treatment of the borders of India, when referring to various authors who "include in India the four satrapies of Gedrosia, Arachosia, Aria, and the Paropanisadae," this

...must have been based on the fact that at some period previous to A.D. 77, when his book was published, these four provinces were actually reckoned as part of India. At what time other than the period of the Mauryan dynasty is it possible that these provinces should have formed part of India?[29]

Smith, limiting Gedrosia to the Malak Mountain Range, further states that

Kabul and Kandahar have frequently been held by the sovereigns of India, and form part of the natural frontier of the country. Herat (Aria) is undoubtedly more remote, but can be held with ease by the power in possesion of Kabul.[29]

Tarn (1922), The Greeks in Bactria and India, p.100, explicitly criticises V.A. Smith (The Early History of India, appendix F, .149 (3rd edition):

Extravagant ideas have been put forward as to what Seleucus did cede [...] The worst has been that of V. A. Smith, who gave Chandragupta the satrapies of Gedrosia, Arachosia, Paropamisadae, and Aria on the strength of Pliny VI, 69, a historical absurdity of unknown origin.

According to Tarn, explicitly criticising Smith for his interpretation of the extent of Aria,[i] the idea that Seleucus handed over more of what is now eastern Afghanistan is an exaggeration originating in statements by Strabo and Pliny the Elder in his Geographia VI, 69, referring not specifically to the lands received by Chandragupta, but rather to the various opinions of geographers regarding the definition of the word "India."[30]

Tarn in return refers to Eratosthenes, who states (in Tarn words) that

Alexander [...] took away from Iran the parts of these three satrapies which lay along the Indus and made of them separate [...] governments or province; it was these which Seleucus ceded, being districts predominantly Indian in blood. In Gedrosia the boundary is known: the country ceded was that between the Median Hydaspes (probably the Purali) and the Indus.

Hemchandra Raaychaudhari, Political history of ancient India, Pg.273[2]:

The ceded country comprised a large portion of Ariana itself, a fact ignored by Tarn. In exchange the Maurya a monarch gave the "comparatively small recompense of 500 elephants. It is believed that the territory ceded by the Syrian king included the four satrapies: Aria, Arachosia, Gedrosia and the Paropanisadai, i.e., Herat, Kandahar, Makran and Kabul. Doubts have been entertained about this by several scholars including Tarn. The inclusion of the Kabul valley within the Maurya Empire is, however, proved by the inscriptions of Asoka, the grandson of Chandragupta, which speak of the Yonas and Gandharas as vassals of the Empire. And the evidence of Strabo probably points to the cession by Seleukos of a large part of the Iranian tableland besides the riparian provinces on the Indus.

According to Raychaudhuri & Mukherjee, it "has been wrongly included in the list of ceded satrapies by some scholars [...] on the basis of wrong assessments of the passage of Strabo [...] and a statement by Pliny."[31]

According to John D. Grainger, "Seleucus "must [...] have held Aria", and furthermore, his "son Antiochos was active there fifteen years later."[32]

According to Sherwin-White and Kuhrt (1993), "The region of Aria is definitely known to have been Seleucid under Seleucus I and Antiochus I as it definitely was after Antiochus III's great campaign in the east against the Parthians and Bactrians. [...] There is no evidence whatever that it did not remain Seleucid, like Drangiana, with which it is linked by easy routes."[33][j]

Notes

[edit]- ^ See this map

- ^ a b c Smith (1914), early History of India Third Edition, p.149: Appendix F, The Extent of the Cession of Ariana hy Seleukos Nikator to Chandragupta Maurya; Smith notes that he was criticised by a Mr.Bevan.

- ^ Nothing can be found out about "Malin", but there is a "Malan" mountain range, that is described as "an offshoot of the Makran Coastal Range", and it was a barrier to Alexander's passage; see Pierre Eggermont (1975), Alexander's Campaign in Sind and Baluchistan and the Siege of the Brahmin Town of Harmatelia, p.58. It seems to be a little to the west of Hingol National Park and Hinglaj Mata Temple.

- ^ The "Median Hydaspes" river is not the Jhelum here. The Purali/Porali river seems to be this river of the Lasbela District, which is prone to devasting floods in the rainy season but running almost dry at other times of the year. If that is correct, Tarn/Eratosthenes are telling us that the extent of the land ceded by the Seleucids to the Mauryas went barely farther west than Karachi, obviously nowhere near Iran.

- ^ Porali, a tributary of the Hingol river.[19]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Trautman_2015_p.235_Makran_coastwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ See this map

- ^ See this map for Porali River.

- ^ Tarn (1922, p. 100, and note 1): "Extravagant ideas have been put forard as to what Seleucus did cede [...] The worst has been that of V. A. Smith, who gave Chandragupta the satrapies of Gedrosia, Arachosia, Paropamisadae, and Aria on the strength of Pliny VI, 69, a historical absurdity of unknown origin."

- ^ "For more than a century, the Seleucids remained in control of the [Drangiana] region. [...] Drangiana was conquered by the Parthians." [1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Tarn 1922, p. 100.

- ^ a b "Appian, the Syrian Wars 11 - Livius".

- ^ a b c Boesche 2003.

- ^ Justin XV.4.12-13[usurped]

- ^ a b Sherwin-White & Kuhrt 1993, p. 93.

- ^ a b Grainger 2014, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Jansari 2023, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Kosmin 2014, p. 33.

- ^ Jansari 2023, p. 32.

- ^ Jansari 2023, p. 33.

- ^ Jansari 2023, p. 35.

- ^ Strabo, Geography, XV, 2, 9

- ^ Strabo, Geography, xv.2.9

- ^ a b Jansari 2023.

- ^ a b c Thapar 1963, p. 16.

- ^ V.A. Smith (1914), Early History of India, p.151

- ^ Eggermont 1975, p. 58.

- ^ Cummings 2004, p. 395-396.

- ^ Narmeen Taimor (2023), An Overview of Rivers of Balochistan, Graana.com

- ^ Trautmann 2015, p. 235.

- ^ Smith 1924, p. 160.

- ^ Grant 2010, p. 50.

- ^ Coningham & Young 2015, p. 452.

- ^ Allchin 1995, p. 208.

- ^ Haig 1894, p. 24.

- ^ a b Smith 1914, p. 149.

- ^ XV, 1, 10

- ^ Pliny, Natural History VI.(23).78. Pliny, Natural History VI.(23).78

- ^ a b Smith 1914, p. 150.

- ^ Tarn 1922, p. 100, and note 1.

- ^ Raychaudhuri & Mukherjee 1997, p. 594.

- ^ Grainger 2014, p. 109.

- ^ Sherwin-White & Kuhrt 1993, p. 79-80.

Sources

[edit]- Allchin, F. R. (1995), "The Mauryan State and Empire", in Allchin, F. R.; Erdosy, George (eds.), The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-37695-2

- Boesche, Roger (2003), "Kautilya's Arthaśāstra on War and Diplomacy in Ancient India", The Journal of Military History, 67 (1): 9, doi:10.1353/jmh.2003.0006, ISSN 0899-3718, S2CID 154243517

- Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015). The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE–200 CE. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-41898-7.

- Cummings, Lewis Vance (2004). Alexander the Great. Grove Press.

- Eggermont, Pierre (1975). Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan and the Siege of the Brahman Town of Harmatelia. Peeters Publishers.

- Grainger, John D. (2014), Seleukos Nikator: Constructing a Hellenistic Kingdom, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-80099-6

- Grant, R. G. (2010). Commanders: History's Greatest Military Leaders. DK Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7566-7341-3.

- Haig, Malcolm Robert (1894). The Indus Delta Country: A Memoir, Chiefly on Its Ancient Geography and History. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Company, Limited.

- Jansari, Sushma (2023). Chandragupta Maurya: The creation of a national hero in India. UCL Press.

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014), The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0

- Raychaudhuri, Hem Chandra; Mukherjee, B.N. (1997) [1923]. Political history of ancient India, from the accession of Parikshit to the extinction of the Gupta dynasty (eight ed.). Oxford University Press India.

- Sherwin-White, Susan; Kuhrt, Amelie (1993). From Samarkhand to Sardis: A New Approach to the Seleucid Empire. University of California Press.

- Smith, V.A. (1914). The Early History Of India Third Edition (third ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Smith, V.A. (1924). The Early History Of India Fourth Edition (fourth ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Tarn, W. W. (1922). The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge University Press.

- Thapar, Romila (1963). Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas. Oxford University Press.

- Trautmann, Thomas (2015). Elephants and Kings: An Environmental History. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-26436-3.