User:Johnrdc/sandbox

The Dominion Land Survey (DLS) is the method used to divide most of Western Canada into one-square-mile sections for agricultural and other purposes. It is based on the layout of the Public Land Survey System used in the United States, but has several differences. The DLS is the dominant survey method in the Prairie provinces, and it is also used in British Columbia along the Railway Belt (near the main line of the Canadian Pacific Railway), and in the Peace River Block in the northeast of the province. These regions were surveyed using the DLS with the consent of the British Columbian government, since unlike the Prairie provinces and Northwest Territories, British Columbia controlled its own public lands upon entering Confederation.[1]

History

[edit]The survey was begun in 1871, shortly after Manitoba and the Northwest Territories became part of Canada. Covering about 800,000 square kilometres (309,000 sq mi), the survey system and its terminology are deeply ingrained in the rural culture of the Prairies. The DLS is the world's largest survey grid laid down in a single integrated system.[2]

The inspiration for the Dominion land survey system was the plan for Manitoba (and later Saskatchewan and Alberta) to be agro- economies. With a large amount of European settlers arriving Manitoba was undergoing a large change, so grasslands and parklands were surveyed settled and farmed[3]. The Dominion land survey system was developed because the farm name and field position descriptions used in northern Europe were not organised or flexible enough, and the township and concession system used in eastern Canada was not satisfactory. The first meridian was chosen at 97° 27’ 28.4” west longitude and was established in 1869. Another 6 meridians were established after. [4]

There are a number of places that are excluded from the survey system. these include; federal lands such as first nation reservations federal parks and air weapon ranges. The surveys don’t encroach on reserves because that land was established before the surveys began. Some parcels of land were held in reserve for school lands, rail roads and for the Hudson’s bay company. Sections 11 and 29 of every township were set aside for schools. Although schools were not always built on these sections, because there was a generally accepted rule that no student should have to walk more than 4 kilometers to school. These lands could be sold to fund the building of a school or given to a farmer who would then dedicate their time to the building of a school house. All odd numbered sections excluding 11 and 29 were earmarked for selection as railway grants. Again these were primarily used as funding for building railroads the main recipient was the Canadian pacific railway received over 26 million acres while other companies land grants totaled almost 6 million acres. When the Hudson’s bay company relinquished their title to the Dominion on July 15 1870, via the deed of surrender it received section 8 and all of section 26 excluding the north east quarter, these lands were gradually sold by the company and in 1984 they donated the remaining 5,100 acres to the Saskatchewan wildlife association. [5]

The surveying of western Canada was divided into 5 basic surveys, The surveys layout was slightly different from one another. The first survey began in 1971 and ended in 1879, it covers some of southern Manitoba and a little of Saskatchewan. The second and smallest survey, 1880, was used in only small area’s of Saskatchewan this system differs from the first survey because rather than running section lines parallel to the eastern boundary these tried running them true north south. The largest and most important of these surveys was the third which covers more land than all the others surveys put together this survey began in 1881. That method of surveying is still used in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. The fourth and fifth survey the fourth and fifth survey were only used in some townships in British Colombia. [6]

Meridians and baselines

[edit]

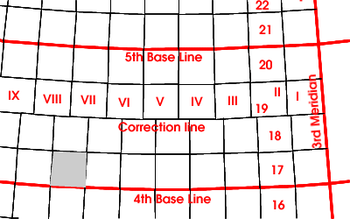

The most important north–south lines of the survey are the meridians:[2]

- The First (also Principal or Prime) Meridian at 97°27′28.41″ west,[7] just west of Winnipeg, Manitoba.

- The Second Meridian at 102° west, which forms the northern part of the Manitoba–Saskatchewan boundary.

- The Third Meridian at 106° west, near Moose Jaw and Prince Albert, Saskatchewan.

- The Fourth Meridian at 110° west, which forms the Saskatchewan–Alberta boundary and bisects Lloydminster.

- The Fifth Meridian at 114° west, which runs through Calgary, Alberta (Barlow Trail is built mostly on the meridian) and Stony Plain, Alberta (48th Street).

- The Sixth Meridian at 118° west, near Grande Prairie, Alberta and Revelstoke, British Columbia.

- The Seventh Meridian at 122° west, between Hope and Vancouver, British Columbia, (Lickman Rd, Chilliwack )

- The Coast Meridian at approximately 122°45′ West, originally established before British Columbia joined the Confederation, was surveyed north from the point where the 49th parallel intersects the sea at Semiahmoo Bay.[1]

The meridians were determined by painstaking survey observations and measurements, and in reference to other benchmarks on the continent, but were determined using 19th century technology. The only truly accurate benchmarks at that time were near the prime meridian in Europe. Benchmarks in other parts of the world had to be calculated or estimated by the positions of the sun and stars. Consequently, although they were remarkably accurate for the time, today they are known to be several hundred metres in error. Before the survey was even completed it was established that for the purposes of laws based on the survey, the results of the physical survey would take precedence over the theoretically correct position of the meridians. This precludes, for example any basis for a boundary dispute between Alberta and Saskatchewan on account of surveying errors.

The main east–west lines are the baselines. The First Baseline is at 49° north, which forms much of the Canada–United States border in the West. Each subsequent baseline is about 24 miles (39 km) to the north of the previous one,[7] terminating at 60° north, which forms the boundary with the Northwest Territories.

Townships

[edit]

Starting at each intersection of a meridian and a baseline and working west (also working east of the First Meridian and the Coast Meridian[2]), nearly square townships are surveyed, which are about 6 miles (9.7 km) in both north–south and east–west extent. There are two tiers of townships to the north and two tiers to the south of each baseline.

Because the east and west edges of townships, called "range lines", are meridians of longitude, they converge towards the North Pole. Therefore, the north edge of every township is slightly shorter than the south. Only along the baselines do townships have their nominal width from east to west. The two townships to the north of a baseline gradually narrow as one moves north, and the two to the south gradually widen as one moves south. Halfway between two base lines, wider-than-nominal townships abut narrower-than-nominal townships. The east and west boundaries of these townships therefore do not align, and north–south roads that follow the survey system have to jog to the east or west. These east–west lines halfway between baselines are called "correction lines".[7]

Townships are designated by their "township number" and "range number". Township 1 is the first north of the First Baseline, and the numbers increase to the north. Range numbers recommence with Range 1 at each meridian and increase to the west (also east of First Meridian and Coast Meridian). On maps, township numbers are marked in Arabic numerals, but range numbers are often marked in Roman numerals; however, in other contexts Arabic numerals are used for both. Individual townships are designated such as "Township 52, Range 25 west of the Fourth Meridian," abbreviated "52-25-W4." In Manitoba, the First Meridian is the only one used, so the abbreviations are even more terse, e.g., "3-1-W" and "24-2-E."

Every township is divided into 36 "sections", each about 1 mile (1.6 km) square. Sections are numbered within townships as follows (north at top):

| 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 |

| 30 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 25 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 18 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

In turn, each section is divided into four "quarter sections" (square land parcels roughly 1/2 mile on a side): southeast, southwest, northwest and northeast. This quarter-section description is primarily used by the agricultural industry. The full legal description of a particular quarter section is "the Northeast Quarter of Section 20, Township 52, Range 25 west of the Fourth Meridian", abbreviated "NE-20-52-25-W4." A section may also be split into as many as 16 legal subdivisions (LSDs). LSDs are commonly used by the oil and gas industry as a precise way of locating wells, pipelines, and facilities. LSDs can be "quarter-quarter sections" (square land parcels roughly 1⁄4 mile (400 m) on a side, comprising roughly 40 acres (160,000 m2) in area)—but this is not necessary. Many are other fractions of a section (a half-quarter section—roughly 80 acres (320,000 m2) in area is common.) LSDs may be square, rectangular, and occasionally even triangular. LSDs are numbered as follows (north at top):

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 |

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

In order to fully understand how the townships, sections, quarter sections, and legal subdivisions were set out, one should refer to the Manual of Instructions for the Survey of Dominion Land.[8]

Occasionally, resource companies assign further divisions within LSDs such as "A, B, C, D etc." for example, to distinguish between multiple sites within an LSD. These in no way constitute an official change to the Dominion Land Survey system, but nonetheless often appear as part of the legal description.

Road allowances

[edit]

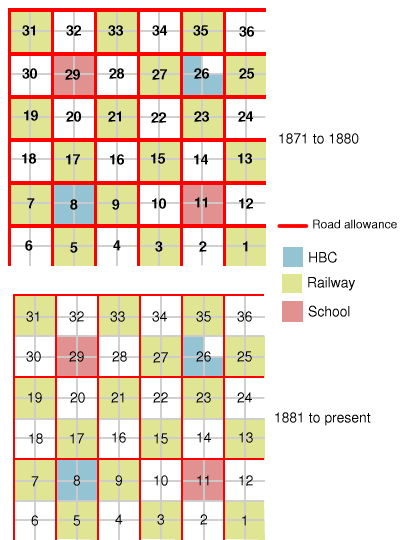

Between certain sections of a township run "road allowances" (but not all road allowances have had an actual road built on them). The road allowances add to the size of the township (they do not cut down the size of the sections): this is the reason base lines are not exactly 24 miles (39 km) apart. In townships surveyed from 1871 to 1880 (most of southern Manitoba, part of southeastern Saskatchewan and a small region near Prince Albert, Saskatchewan), there are road allowances of 1+1⁄2 chains (30 m) surrounding every section. In townships surveyed from 1881 to the present, road allowances are reduced both in width and in number. They are 1 chain (20 m) wide and run north–south between all sections; however, there are only three east–west road allowances in each township, on the north side of sections 7 to 12, 19 to 24 and 31 to 36. This results in a road allowance every mile going east-west, and a road allowance every two miles going north-south. This arrangement reduced land allocation for roads, but still provides road-access to every quarter-section. Road allowances are one of the differences between the Canadian DLS and the American Public Land Survey System, which leaves no extra space for roads.

Special sections

[edit]Certain sections of townships were reserved for special purposes:

- As part of the deal that transferred Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company to Canada, the HBC retained five per cent of the "fertile belt" (south of the North Saskatchewan and Winnipeg rivers). Therefore Section 8 and three-quarters of Section 26 were assigned to the company. Additionally, the fourth quarter of Section 26 in townships whose numbers were divisible by five also belonged to the HBC in order to give the company exactly five per cent. Although the HBC sold all these sections long ago, they are still often locally called "the Bay section" today.

- The odd-numbered sections (except 11 and 29) were often used for railway land-grants. The Prairies could not be settled without railways, so the Dominion government habitually granted large tracts of land to railway companies as an incentive to build lines. Notably, the Canadian Pacific Railway was granted 25,000,000 acres (100,000 km2) for the construction of its first line from Ontario to the Pacific. These sections are colloquially called CPR sections regardless of the railway they were originally granted to.

- Sections 11 and 29 were school sections. When school boards were formed, they gained title to these sections, which were then sold to fund the initial construction of schools. The rural school buildings were often as not located on school sections; frequently, land trades were made between landowners and the school for practical reasons.

- The remaining quarter sections were available as homesteads under the provisions of the Dominion Lands Act, the federal government's plan for settling the North-West. A homesteader paid a $10 fee for a quarter section of his choice. If after three years he had cultivated 30 acres (12 ha) and had built a house (often just a sod house), he gained title to the quarter. Homesteads were available as late as the 1950s, but the bulk of the settlement of the Prairies was 1885 to 1914.

Legal surveys conducted before and after the Dominion Land Survey grid was laid out often have their own legal descriptions and delineations. Early settlement lots still retain their own original legal descriptions, but often have townships superimposed over them for the sake of convenience or for certain tasks. Urban developments superimpose new survey lots and plans over the older section and township grid also.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Crown Lands: A History of Survey Systems, by W.A. Taylor, B.C.L.S., 1975. 5th Reprint, 2004. Registries and Titles Department, Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management. Victoria, British Columbia.

- ^ a b c Western Land Grants (1879-1930), Library and Archives Canada

- ^ [Hanuta, Irene. "A dominion land survey map of the Red River Valley." Manitoba History 58 (2008): 23+.. Web. 15 Nov. 2012.)], Gale World History In Context

- ^ Wolfe,Bertram, McKercher, Robert.B. (1986.). "Understanding Western canada’s Dominion Land survey system". University Extension Press. pp. 1–2.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Wolfe,Bertram, McKercher, Robert.B. (1986.). "Understanding Western canada’s Dominion Land survey system". University Extension Press. pp. 9–11.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Wolfe,Bertram, McKercher, Robert.B. (1986.). "Understanding Western canada’s Dominion Land survey system". University Extension Press. pp. 11–14.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c Larmour, Judy (2005). Laying Down the Lines: A History of Land Surveying in Alberta. Brindle and Glass,. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-1-897142-04-2. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Manual of Instructions for the Survey of Dominion Lands, 1st to 10th Editions, Surveyor General Branch, Earth Sciences Sector, Natural Resources Canada

Further reading

[edit]Dennis, John Stoughton younger (1856-1938). A short history of the surveys performed under the Dominion lands system, 1869 to 1889. Ottawa: s.n, 1892.

McKercher, Robert B and Bertram Wolf (1986). Understanding Western Canada's Dominion Land Survey System. Saskatoon: Division of Extension and Community Relations, University of Saskatchewan.

Oliver, J. (2007) ‘The paradox of progress: land survey and the making of agrarian society in colonial British Columbia’. In L. McAtackney, M. Palus and A. Piccini (eds.) Contemporary and Historical Archaeology in Theory, pp. 31–38. Oxford: BAR, International Series, S1677.

Thomson, D.W. (1966 & 1967) Men and Meridians: The History of Surveying and Mapping in Canada, 3 vols. Ottawa: Department of Energy, Mines and Resources.

External links

[edit]- Hubbard, Bill (2009). American Boundaries. University of Chicago Press. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-226-35591-7. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- Index to Townships in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia: Showing the Townships for which Official and Preliminary Plans have been issued up to January 1st, 1929, made by the Topographical Survey of Canada, Department of the Interior; available online from Library and Archives Canada

- Convert Alberta and Saskatchewan Townships into latitude & longitude