User:Issabei/sandbox

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2009) |

| Grammatical features |

|---|

Animacy (antonym: inanimacy) is a grammatical and semantic feature, existing in some languages, expressing how sentient or alive the referent of a noun is.[1] Widely expressed, animacy is one of the most elementary principles in languages around the globe and is a distinction acquired as early as six months of age.[2] This feature is linked to how we usually think and communicate because languages tend to give more importance to things that are seen as alive or sentient. [1]

Concepts of animacy constantly vary beyond a simple animate and inanimate binary; many languages function off an hierarchical general animacy scale that ranks animacy as a "matter of gradience".[1] Typically (with some variation of order and of where the cutoff for animacy occurs), the scale ranks humans above animals, then plants, natural forces, concrete objects, and abstract objects, in that order. This hierarchy reflects cultural and cognitive actors that influence the perception of what is considered alive. In referring to humans, this scale contains a hierarchy of persons, ranking the first- and second-person pronouns above the third person, partly a product of empathy, involving the speaker and interlocutor.[1] In many languages, the distinction has many functional implications, influencing verb agreement, topicality, and sentence structure.

Animacy Hierarchy

[edit]The Animacy Hierarchy is a framework that organizes entities based on their level of animacy, influencing linguistic structures and cognitive processes.[3] Originating from the works of Silverstein and Dixon, the hierarchy ranks entities from most to least animate, typically as: humans > animals > inanimate objects, with finer distinctions such as 1st/2nd person pronouns > 3rd person pronouns > proper nouns > common animate nouns > inanimate nouns. This hierarchy reflects inherent features like sentience and movement, cultural and conceptual factors, and contextual prominence.[1] It shapes linguistic phenomena such as case marking, verb agreement, agentivity, and word order, with animate entities often prioritized in grammatical roles.

Although generally consistent, the hierarchy varies across languages due to cultural beliefs, temporary discourse contexts, and pragmatic needs. The distinction between formal grammatical animacy, which generally operates in binary terms (e.g., human/nonhuman), and conceptual animacy, which reflects a graded, context-sensitive perception of animacy, underscores its complexity. Ultimately, the Animacy Hierarchy provides insights into how languages encode animacy distinctions while accommodating cultural and cognitive variability.Cite error: There are <ref> tags on this page without content in them (see the help page).

Examples of languages in which an animacy hierarchy is important include the Totonac language in Mexico and the Southern Athabaskan languages (such as Western Apache and Navajo) whose animacy hierarchy has been the subject of intense study.[1] The Tamil language has a noun classification based on animacy.[1]

Changes to model

[edit]Some authors also consider the animacy as a gradative feature, and that certain things in the world can have varying degrees of animacy (such as robots - see the section on Japanese). This idea culminates in a radial conception of animacy, as opposed to the original hierarchical conception.[1]

Types of Animacy

[edit]De Swart and de Hoop (2018)[4] emphasize the importance of distinguishing between three types of animacy: biological, conceptual, and grammatical. Each of these types plays a unique role in understanding how humans perceive and express the distinction between animate and inanimate entities.

Biological animacy refers to entities that are biologically alive and is defined by physical properties like the capacity to die. Living entities, such as humans, animals, and plants, are considered biologically "animate," whereas non-living entities, like rocks or water, are classified as "inanimate." This type of animacy forms the foundation of how humans instinctively categorize the world around them.[4]

Conceptual animacy is based on the speaker’s perception and cultural background. It concerns what is perceived as alive, influenced by the “ego’s” perspective and societal beliefs. This type often diverges from biological animacy.[4] For example, in some cultures or languages, inanimate objects like the sun or mountains are considered "animate" due to mythology or cultural beliefs. Conceptual animacy reflects how humans personify or attribute agency to non-living entities.[4]

Grammatical animacy demonstrates how biological and conceptual animacy are represented in the grammar of languages. It operates as a semantic feature or condition influencing linguistic structures, such as verb agreement or case marking. For instance, in Russian, animacy distinctions affect object marking in sentences; animate nouns, such as humans and animals, are treated differently than inanimate nouns. This type of animacy illustrates the interaction between cognitive perceptions and linguistic systems.[4]

The animacy hierarchy (e.g., human > animal > inanimate) is widely applied in linguistic analysis to explain various phenomena. Animate entities are more likely to act as agents or subjects in sentences (agentivity), receive distinct grammatical treatment in case marking or agreement, and be referenced explicitly in discourse.[4] Additionally, animacy hierarchies are not static; cultural factors or temporary discourse contexts can shift these classifications.

Although animacy distinctions appear universally across languages, their specific implementation varies. For example, Navajo uses animacy to govern verb marking, while Slavic languages reflect animacy distinctions in noun declensions. However, the universality of animacy as a linguistic feature is debated due to its variability across languages.[4] Cultural and functional factors can lead to unique animacy hierarchies, showing that animacy is both a universal and context-dependent concept.

Techniques for Expressing Animacy in Language

[edit]Animacy can function in language as either a feature (AnimF) or a condition (AnimC), with some languages employing both simultaneously. These two roles highlight distinct ways animacy interacts with linguistic systems.[1]

Animacy as a Feature (AnimF) operates as a semantic characteristic that influences specific word or morpheme classes.[1] It is used to encode grammatical values such as person, number, case, and gender, introducing a semantic distinction based on animacy. AnimF may involve changing the shape of a word or adding morphological material to reflect whether an entity is animate or inanimate. However, it does not fundamentally alter the grammatical feature itself; instead, it adds a layer of semantic meaning.[1] For instance, it often distinguishes between animate and inanimate entities while maintaining the existing grammatical structure.

Animacy as a Condition (AnimC) demonstrates how animacy governs various grammatical features within a language. It influences linguistic paradigms by reorganizing them based on the animacy of entities.[1] For example, in Bunak, a prefixed bound pronoun is attached to a verb only if the direct object is animate. Animacy also affects gender agreement, where animacy distinctions can control gender markers even in systems that are not primarily animacy-based.[1] Similarly, case marking and agreement controllers may vary depending on animacy. For instance, certain languages use different case markers or allomorphs for animate versus inanimate nouns. AnimC showcases how semantic properties like animacy can streamline linguistic structures and reduce morphological complexity.[1]

Affixation

[edit]Prefixes or suffixes are added to roots or stems to mark animacy distinctions. Prefixation typically involves free elements, clitics, or true prefixes, while suffixation often adds markers for features like case or number alongside animacy.[1]

Alternation

[edit]This involves changing the morphological or phonological structure of a word without adding new material. It may include pure alternation, adjustments in grammatical features, or techniques to either create or avoid syncretism (merging distinct forms).[1]

Overt Free Elements

[edit]Independent words are introduced in sentences to signify animacy, rather than altering the morphology of existing words.[1]

Reduplication

[edit]Parts of a word are repeated, often in pluralization, to mark distinctions between animate and inanimate nouns.[1]

Zero-Marking

[edit]In some languages, animate entities are marked explicitly, while inanimate entities remain unmarked.[1]

Morpheme Order

[edit]The arrangement of morphemes within a word or phrase can reflect animacy distinctions.[1]

Complex Techniques

[edit]These involve multiple processes, such as combining morphological and phonological strategies, to mark animacy distinctions.[1]

Morphophonemic Techniques

[edit]Phonological changes such as vowel alternation, nasalization, tone, stress, and glottalization are used to express animacy distinctions.[1]

Mixed Techniques

[edit]These combine two or more of the above methods, such as blending morphological and morphophonemic strategies, to create more nuanced animacy markers.[1]

Contentions

[edit]Animacy as a "subgender"

[edit]While animacy is viewed as primarily semantic when approached diachronically, a synchronic view suggests animacy as a sublevel of gender.[5] Syntactic gender is defined through patterns in agreement, not necessarily semantic value.[5] For example, Russian has "common gender" nouns that refer to traditionally masculine roles but act as syntactically feminine.[5]

Animacy occurs as a subgender of nouns and modifiers (and pronouns only when adjectival) and is primarily reflected in modifier-head agreement (as opposed to subject-predicate agreement).[5]

Arbitrariness

[edit]Despite attempts to standardize measures of animacy throughout languages, some evidence suggests that animacy attribution is arbitrary.

For example, in Romance languages such as Spanish, animacy is commonly associated with gender by the literature and said to encode a "primitive form of animism". However, this does not explain the fact that Latin non-neuter pronouns (such as la in Spanish, as in "la mesa", or "the table") can have inanimate referents.[6]

In Algonquian languages, there is debate on whether animacy distinction derives from 'power' dynamics or an Algonquian worldview. [7] Looking at Plains Cree, there are unclear characteristics that might make the animate word sôminis 'raisin' have more 'power' than the inanimate word mitêhimin 'strawberry'.[7] Also, considering that "the cultural role and status of tobacco differed little among the Algonquian peoples", it is unclear how the worldview would be so affected that "the word for 'tobacco' is animate in Meskwaki, Cree, Menomini, and Ojibwe, while inanimate in Munsee, Unami, and Eastern Abenaki". [7] This led Gillon to the assumption that animacy marking is arbitrary. [7]

Implications

[edit]Thematic roles in noun usage

[edit]A noun essentially requires the traits of animacy in order to receive the role of Actor and Experiencer. Additionally, the Agent role is generally assigned to the NP with highest ranking in the animacy hierarchy – ultimately, only animate beings can function as true agents.[2] Similarly, languages universally tend to place animate nouns earlier in the sentence than inanimate nouns.[2] Animacy is a key component of agency – combined with other factors like "awareness of action".[8] Agency and animacy are intrinsically linked – with each as a "conceptual property" of the other.[8]

Split ergativity

[edit]Animacy can also condition the nature of the morphologies of split-ergative languages.[2] In such languages, participants more animate are more likely to be the agent of the verb, and therefore are marked in an accusative pattern: unmarked in the agent role and marked in the patient or oblique role.

Likewise, less animate participants are inherently more patient-like, and take ergative marking: unmarked when in the patient role and marked when in the agent role.[2] The hierarchy of animacy generally, but not always, is ordered:

1st person > 2nd person > 3rd person > proper names > humans > - non-humans

- animates

> inanimates

The location of the split (the line which divides the inherently agentive participants from the inherently patientive participants) varies from language to language, and, in many cases, the two classes overlap, with a class of nouns near the middle of the hierarchy being marked for both the agent and patient roles.[2]

Examples

[edit]Indo-European Languages

[edit]English

[edit]The distinction between he, she, and other personal pronouns, on one hand, and it, on the other hand is a distinction in animacy in English and in many Indo-European languages.[1] The same can be said about distinction between who and what. Some languages, such as Turkish, Georgian, Spoken Finnish and Italian, do not distinguish between s/he and it. In Finnish, there is a distinction in animacy between hän, "he/she", and se, "it", but in Spoken Finnish se can mean "he/she".[1] English shows a similar lack of distinction between they animate and they inanimate in the plural.

Additionally, in English, the higher animacy a referent has, the less preferable it is to use the preposition of for possession (that can also be interpreted in terms of alienable or inalienable possession):[9]

- My face is correct while the face of mine would sound strange.

- The man's face and the face of the man are both correct, but the former is preferred.

- The clock's face and the face of the clock are both correct.

Greek

[edit]In Greek, Animacy exhibits a weak influence on sentence structure compared to other languages like English. In the case of modern Greek, we see a difference in construction in the presence of animacy. where animate objects are marked using nominative-accusative alignment. Animate entities take the masculine article, and inanimate entities take the neuter article[1]

Είδα

Eída

Saw.1st.Sg.Past

τον

ton

Def.Masc.Sg.Acc

σερβιτόρο

servitóro

waiter.Masc.Sg.Acc

"I saw the waiter"

Ο

O

Def.Nom

σερβιτόρος

servitóros

waiter.Masc.Nom

με

me

PRO.1st.Sg.Acc

είδε

eíde

Saw.3rd.Sg.Past

"The waiter saw me"

As we see in (3), word order doesn't matter - the example is less often used in conversation, but still grammatical. However, this markedness between nominative and accusative forms is lost with inanimate objects. Word order marks the subject and object instead in this case.

Με

Me

PRO.1st.Sg.Acc

είδε

eíde

Saw.3rd.Sg.Past

o

o

Def.Masc.Sg.Nom

σερβιτόρος

servitóros

waiter.Masc.Sg.Nom

"The waiter saw me"

Sinhala

[edit]In spoken Sinhala, there are two existential/possessive verbs: හිටිනවා hiţinawā / ඉන්නවා innawā are used only for animate nouns (humans and animals), and තියෙනවා tiyenawā for inanimate nouns (like non-living objects, plants, things):[1]

මිනිහා

minihā

man

ඉන්නවා

innawā

there is/exists

(animate)

'There is the man'

වතුර

watura

water

තියෙනවා

tiyenawā

there is/exists

(inanimate)

'There is water'

Spanish

[edit]In Spanish, the preposition a (meaning "to" or "at") has gained a second role as a marker of concrete animate direct objects:[10]

Veo esa catedral. "I can see that cathedral." (inanimate direct object) Veo a esa persona. "I can see that person." (animate direct object) Vengo a España. "I come to Spain." (a used in its literal sense)

The usage is standard and is found around the Spanish-speaking world.

Spanish personal pronouns are generally omitted if the subject of the sentence is obvious, but when they are explicitly stated, they are used only with people or humanized animals or things.[10] The inanimate subject pronoun in Spanish is ello, like it in English (except "ello" can only be used to refer to verbs and clauses, not objects, as all nouns are either masculine or feminine and are referred to with the appropriate pronouns).[10]

Spanish direct-object pronouns (me, te, lo, la, se, nos, os, los, las) do not differentiate between animate and inanimate entities, and only the third persons have a gender distinction. Thus, for example, the third-person singular feminine pronoun, la, could refer to a woman, an animal (like mariposa, butterfly), or an object (like casa, house), if their genders are feminine.[10]

In certain dialects, there is a tendency to use le (which is usually an indirect object pronoun, meaning "to him/her") as a direct-object pronoun, at the expense of the direct-object pronouns lo/la, if the referent is animate.[10] That tendency is especially strong if (a) the pronoun is being used as a special second-person pronoun of respect, (b) the referent is male, (c) certain verbs are used, (d) the subject of the verb happens to be inanimate.[10]

Slavic languages

[edit]Slavic languages that have case (all of them except Bulgarian and Macedonian) have a somewhat complex hierarchy of animacy in which syntactically animate nouns may include both animate and inanimate objects (like mushrooms and dances).[11] Overall, the border between animate and inanimate places humans and animals in the former and plants, etc., in the latter, thus basing itself more so on sentience than life.[11]

Animacy functions as a subgender through which noun cases intersect in a phenomenon called syncretism, which here can be either nominative-accusative or genitive-accusative. Inanimate nouns have accusative forms that take on the same forms as their nominative, with animate nouns marked by having their accusative forms resemble the genitive.[5]

For example, syncretism in Polish conditioned by referential animacy results in forms like the following:

- NOM stół 'table' -> ACC stół, like nom -> GEN stołu (exhibiting nom-acc syncretism);

- NOM kot 'cat' -> ACC kota, like gen -> GEN kota (exhibiting gen-acc syncretism).[5]

That syncretism also occurs when restricted by declension class, resulting in syncretism in multiple pronominal forms, such as the Russian reflexive pronoun себя (sebja), personal pronouns, and the indefinite interrogative and relative pronoun kto.[5]

In their plural forms, nouns of all genders may distinguish the categories of animate vs. inanimate by that syncretism, but only masculine nouns of the first declension (and their modifiers) show it in the singular (Frarie 1992:12), and other declensions and genders of nouns "restrict (morphological) expression of animacy to the plural" (Frarie 1992:47).

- Masc nouns that show acc-gen (sg & plural) syncretism: муж [muʂ] husband, сын [sɨn] son, лев [lʲef] lion, конь [konʲ] horse.[11]

- Fem animate nouns that show acc-gen (plural) syncretism: женщина [ˈʐɛnʲɕːɪnə] woman, лошадь [ˈɫoʂətʲ] horse.[11]

- Neut animate nouns that show acc-nom (sg) and acc-gen (plural) syncretism: животное 'animal', насекомое 'insect'.

Elsewhere, animacy is displayed syntactically, such as in endings of modifiers for masc nouns of the second declension.[11]

Proto-Indo-European Languages

[edit]Because of the similarities in morphology of feminine and masculine grammatical gender inflections in Indo-European languages, there is a theory that in an early stage, the Proto-Indo-European language had only two grammatical genders: "animate" and "inanimate/neuter"[1]; the most obvious difference being that inanimate/neuter nouns used the same form for the nominative, vocative, and accusative noun cases. The distinction was preserved in Anatolian languages like Hittite, all of which are now extinct.[1]

The animate gender would then later, after the separation of the Anatolian languages, have developed into the feminine and masculine genders.[1] The plural of neuter/inanimate nouns is believed to have had the same ending as collective nouns in the singular, and some words with the collective noun ending in singular were later to become words with the feminine gender.[1] Traces can be found in Ancient Greek in which the singular form of verbs was used when they referred to neuter words in plural.[1] In many Indo-European languages, such as Latin and the Slavic languages, the plural ending of many neuter words in the merged nominative–accusative–vocative corresponds to the feminine singular nominative form.[1]

Algonquian Languages

[edit]Plains Cree

[edit]In Plains Cree, nouns that are animate usually refer to living things, stones or rocks, and celestial bodies, or select items of clothing, utensils, body parts and machines. [12] Inanimate nouns usually refer to items like most utensils, machines, clothing and buildings, but can also include living objects like body parts. [12]

The effects of animacy can be coded on demonstratives, verb stems, and in some nominal affixation (i.e., plural), similar to gender/classifier systems in other languages. [13]

With looking to pluralize nouns, animate affixes always end with a -k inanimate affixes always end with -a. [12] There are a few exceptions, and a table has been created to show how the final letter of the singular form can help predict which affix to use for the plural form. [12]

| Animate | Inanimate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| singular stem ending | plural affix | singular stem ending | plural affix |

| most common | -ak | most common | -a |

| a_# | -k | k_# | -wa |

| k_#,

sometimes m_# |

-wak | i_# | -a replaces -i |

With verbs, there are 4 types based on whether it is a Transitive verb or an Intransitive verb, and whether they affect animate or inanimate nouns.[12] Each type will have it's own rules and patterns regarding grammar like conjugation and modes. Examples can be shown using the verb 'eat' as it has forms using 3 out of the 4 verb types, and incorporating the Inanimate noun wiyās 'meat'. The 4 types are:

- Transitive Animate Verb (VTA)

- expresses actions that affect, or are stimulated by, animate nouns

- Animate Subject, Animate Object

- Transitive Inanimate Verb (VTI)

- expresses actions that affect, or are stimulated by, inanimate nouns

- Animate Subject, Inanimate Object

- Animate Intransitive Verb (VAI)

- expresses an action by an animate noun, but are not transferred to anyone or anything

- Animate Subject, No Object

- Inanimate Intransitive Verb (VII)

- expresses states, conditions, happenings, and occurrences

- Inanimate Subject, No Object

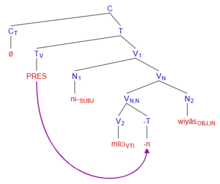

The verb 'eat' has 3 distinct verb stems depending on which verb type it is: mīciso (VAI), mīci (VTI), and mow (VTA). A syntax tree is shown to illustrate how the inanimate noun wiyās 'meat' can be incorporated. In sentence (1), we see a grammatical example where VTI mīci 'eat' successfully selects a subject (SUBJ), and an inanimate object (OBJ,IN). In sentence (2), we see an ungrammatical example where VTA mow 'eat' successfully selects a subject (SUBJ) but unsuccessfully selects an animate object since wiyās is inanimate.

ni-mīci-n

I-eat-PRES

wiyās

meat

I-eat meat

*ni-mow-āw

I-eat-PRES

wiyās

meat

I eat meat

Na-Dene Languages

[edit]Navajo (Diné)

[edit]Like most other Athabaskan languages, Southern Athabaskan languages show various levels of animacy in their grammar, with certain nouns taking specific verb forms according to their rank in this animacy hierarchy. For instance, Navajo (Diné) nouns can be ranked by animacy on a continuum from most animate (a human) to least animate (an abstraction)[14]:

- Adult human/lightning > infant/big animal > medium-sized animal > small animal > natural force > abstraction

Generally, the most animate noun in a sentence must occur first while the noun with lesser animacy occurs second.[14] If both nouns are equal in animacy, either noun can occur in the first position. Both sentences (1) and (2) are correct. The yi- prefix on the verb indicates that the first noun is the subject and bi- indicates that the second noun is the subject.

Ashkii

boy

at’ééd

girl

yiníł’į́

yi-look

'The boy is looking at the girl.'

At’ééd

girl

ashkii

boy

biníł’į́

bi-look

'The girl is being looked at by the boy.'

Sentence (3), however, sounds wrong to most Navajo speakers because the less animate noun occurs before the more animate noun:

*Tsídii

bird

at’ééd

girl

yishtąsh

yi-pecked

*'The bird pecked the girl.'

In order to express that idea, the more animate noun must occur first, as in sentence (4):

At’ééd

girl

tsídii

bird

bishtąsh

bi-pecked

'The girl was pecked by the bird.'

There is evidence suggesting that the word order itself is not the important factor.[14] Instead, the verb construction usually interpreted as the passive voice (e.g. "the girl was pecked by the bird") instead indicates that the more animate noun allowed the less animate noun to perform the action (e.g. "the girl let herself be pecked by the bird"). The idea is that things ranked higher in animacy are presumed to be in control of the situation, and that the less-animate thing can only act if the more-animate thing permits it.

Japonic Languages

[edit]Japanese

[edit]Although nouns in Japanese are not marked for animacy, it has two existential/possessive verbs; one for implicitly animate nouns (usually humans and animals) and one for implicitly inanimate nouns (often non-living objects and plants).[15] The verb iru (いる, also written 居る) is used to show the existence or possession of an animate noun. The verb aru (ある, sometimes written 在る when existential or 有る when possessive) is used to show the existence or possession of an inanimate noun.

An animate noun, here 'cat', is marked as the subject of the verb with the subject particle ga (が), but no topic or location is marked. That implies the noun is indefinite and merely exists.

猫

Neko

cat

が

ga

SBJ

いる

iru.

to exist

'There is a cat.'

If the noun is not animate, such as a stone, instead of a cat, the verb iru must be replaced with the verb aru (ある or 有る [possessive] / 在る [existential, locative]).

石

Ishi

stone

が

ga

SBJ

ある

aru.

to exist

'There is a stone.'

In some cases in which "natural" animacy is ambiguous, whether a noun is animate or not is the decision of the speaker, as in the case of a robot, which could be correlated with the animate verb (to signify sentience or anthropomorphism) or with the inanimate verb (to emphasise that is a non-living thing).[15]

ロボット

Robotto

robot

が

ga

SBJ

いる

iru.

to exist

'There is a robot' (emphasis on its human-like behavior).

ロボット

Robotto

robot

が

ga

SBJ

ある

aru.

to exist

'There is a robot' (emphasis on its status as a nonliving thing).

Ryukyuan Languages

[edit]The Ryukyuan languages, spoken in the Ryukyu Islands, agree in animacy in their case systems.[16] Ryukyuan languages include two dialects, Okinawan and Amami. They show that animacy influences different case markings.

In Okinawan, just like in Japanese, the case marking is completely absent, and the subject of a clause is given either the genitive case (-nu) or nominative case (-ga). inanimate objects often get the genitive case -nu whereas the animated subjects get the nominative case -ga. [17]

Taa-ga

who-NOM

Miyara

Miyara

shinshii-nu

teacher-GEN

sumuchi-∅

book-ACC

koota

bought

ga?

Q

‘Who bought Prof. Miyara’s book?’

Nuu-"nu"

what-GEN

'utitoo

fallen

ga?

Q

"what has fallen over there"

In Ryukyuan languages, animate objects are ranked higher than inanimate objects in the animacy hierarchy, as follows:[17]

- First Person Pronoun > Second Person Pronouns > Third Person > Kin > Human > Animate > Inanimate

Afro-Asiatic Languages

[edit]Arabic

[edit]In Classical and Modern Standard Arabic and some other varieties of Arabic, animacy has a limited application in the agreement of plural and dual nouns with verbs and adjectives.[18] Verbs follow nouns in plural agreement only when the verb comes after the subject. When a verb comes before an explicit subject, the verb is always singular.[citation needed] Also, only animate plural and dual nouns take plural agreement; inanimate plural nouns are always analyzed as singular feminine or plural feminine for the purpose of agreement. Thus, sentence (1) is masculine plural agreement:

While sentence (2) is feminine singular:

الطائرات

Al-ṭā’irāt

تطير

taṭīr

إلى

’ilā

ألمانيا

’Almāniyā

The planes fly to Germany.

Compare them to sentences (3) and (4):

تطير

Taṭīr

المهندسات

al-muhandisāt

إلى

’ilā

ألمانيا

’Almāniyā

The [female] engineers fly to Germany.

المهندسات

Al-muhandisāt

يطرن

yaṭirna

إلى

’ilā

ألمانيا

’Almāniyā

The [female] engineers fly to Germany.

In general, Arabic divides animacy between عاقل (thinking, or rational) and غير عاقل (unthinking, or irrational).[18] Animals fall in the latter category, but their status may change depending on the usage, especially with personification.[citation needed] Different writers might use either sentence (5) or (6) for "The ravens fly to Germany", for example:

الغربان

Al-ġurbān

يطيرون

yaṭīrūn

إلى

’ilā

ألمانيا

’Almāniyā

The ravens fly to Germany.

الغربان

Al-ġurbān

تطير

taṭīr

إلى

’ilā

ألمانيا

’Almāniyā

The ravens fly to Germany.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Santazilia, Ekaitz (2022-11-14), Animacy and Inflectional Morphology across Languages, Brill, doi:10.1163/9789004513068, ISBN 978-90-04-51306-8, S2CID 256298064, retrieved 2024-02-07

- ^ a b c d e f Szewczyk, Jakub M.; Schriefers, Herbert (2010). "Is animacy special? ERP correlates of semantic violations and animacy violations in sentence processing". Brain Research. 1368: 208–221. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.070. PMID 21029726. S2CID 33461799.

- ^ Dixon, R. M. W. (2002). Ergativity. Cambridge studies in linguistics (Transferred to digital print ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr. ISBN 978-0-521-44898-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Swart, Peter de; Hoop, Helen de (2018-06-01). "Shifting animacy". Theoretical Linguistics. 44 (1–2): 1–23. doi:10.1515/tl-2018-0001. ISSN 1613-4060.

- ^ a b c d e f g Klenin, Emily (1983). Animacy in Russian: a new interpretation. Columbus, OH: Slavica Publishers.

- ^ Manoliu, M. (2014). Cognitive categories and grammatical gender from Latin to Romance.

- ^ a b c d Siddiqi, Daniel; Barrie, Michael; Gillon, Carrie; Mathieu, Éric, eds. (2020). The Routledge handbook of North American languages. Routledge handbooks in linguistics. New York London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-315-21063-6.

- ^ a b Yamamoto, Mutsumi (2006). Agency and impersonality: Their linguistic and cultural manifestations. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins Pub. Co. p. 36.

- ^ Ji, Jie; Liang, Maocheng (2018-04-01). "An animacy hierarchy within inanimate nouns: English corpus evidence from a prototypical perspective". Lingua. 205: 71–89. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2017.12.017. ISSN 0024-3841.

- ^ a b c d e f Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española. (2005). Diccionario panhispánico de dudas. Bogotá: Santillana Ediciones Generales. ISBN 958-704-368-5.

- ^ a b c d e Frarie, Susan E. (1992). Animacy in Czech and Russian. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- ^ a b c d e Okimāsis, Jean L. (2018). Cree: Language of the Plains / nēhiyawēwin: paskwāwi-pīkiskwēwin.

- ^ Muehlbauer, Jeffrey (2012). "The Relation of Switch-Reference, Animacy, and Obviation in Plains Cree". International Journal of American Linguistics. 78 (2): 203–238. doi:10.1086/664480. ISSN 0020-7071.

- ^ a b c Young, Robert W.; Morgan, William (1998). The Navajo language: a grammar and colloquial dictionary (2., rev. ed., 4. print ed.). Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-1014-9.

- ^ a b Yamamoto, Mutsumi, ed. (2010). Animacy and reference: a cognitive approach to corpus linguistics. Studies in language companion series 0165-7763. Amsterdam Philadelphia: J. Benjamins Pub. ISBN 978-90-272-9876-8.

- ^ Shimoji, Michinori; Pellard, Thomas, eds. (2010). An Introduction to Ryukyuan Languages. Tokyo: ILCAA. ISBN 9784863370722. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ^ a b Hiraiwa, K. (2022). Animacy hierarchy and case/agreement in Okinawan. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America, 7(1), 5255. https://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v7i1.5255

- ^ a b Khwaileh, Tariq; Body, Richard; Herbert, Ruth (2017-05-01). "Lexical retrieval after Arabic aphasia: Syntactic access and predictors of spoken naming". Journal of Neurolinguistics. 42: 140–155. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroling.2017.01.001. ISSN 0911-6044.

Sources

[edit]- Crespo Cantalapiedra, I. (2024). La diversidad en las lenguas: la animacidad. Online book (in Spanish).

- Frishberg, Nancy. (1972). Navajo object markers and the great chain of being. In J. Kimball (ed.), Syntax and semantics, vol. 1, p. 259–266. New York: Seminar Press.

- Hale, Kenneth L. (1973). A note on subject–object inversion in Navajo. In B. B. Kachru, R. B. Lees, Y. Malkiel, A. Pietrangeli, & S. Saporta (eds.), Issues in linguistics: Papers in honor of Henry and Renée Kahane, p. 300–309. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Thomas E. Payne, 1997. Describing morphosyntax: A guide for field linguists. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-58224-5.

- Young, Robert W., & Morgan, William, Sr. (1987). The Navajo language: A grammar and colloquial dictionary (rev. ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-1014-1.

- Shimoji, M., & Pellard, T. (Eds.). (2015). An introduction to Ryukyuan languages. Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa (ILCAA), Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. https://lingdy.aa-ken.jp/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/2015-papers-and-presentations-An_introduction_to_Ryukyuan_languages.pdf

- Hiraiwa, K. (2022). Animacy hierarchy and case/agreement in Okinawan. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America, 7(1), 5255. https://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v7i1.5255

- Santazilia, E., & Brill Online Books. (2023). Animacy and inflectional morphology across languages. Brill. https://brill.com/display/title/62101

- Ji, J., & Liang, M. (2018). An animacy hierarchy within inanimate nouns: English corpus evidence from a prototypical perspective. Lingua, 205, 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2017.12.017