User:HistoryofIran/Gondophares

| This is a Wikipedia user page. This is not an encyclopedia article or the talk page for an encyclopedia article. If you find this page on any site other than Wikipedia, you are viewing a mirror site. Be aware that the page may be outdated and that the user in whose space this page is located may have no personal affiliation with any site other than Wikipedia. The original page is located at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:HistoryofIran/Gondophares. |

| Gondophares | |

|---|---|

| |

| Indo-Parthian king | |

| Reign | c. 19 – c. 46 |

| Successor | Ortaghnes (Drangiana and Arachosia) Abdagases I (Gandhara) |

| Died | 46 |

| House | House of Suren |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

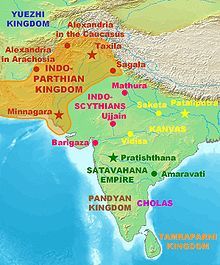

Gondophares I was the founder of the Indo-Parthian Kingdom and its most prominent king, ruling from 19 to 46. A member of the House of Suren, he belonged to a line of local princes who had governed the Parthian province of Drangiana since its disruption by the Indo-Scythians in c. 129 BC. During his reign, his kingdom became independent from Parthian authority and was transformed into an empire, which encompassed Drangiana, Arachosia, and Gandhara.[1] He is generally known from the dubious Acts of Thomas, the Takht-i-Bahi inscription, and coin-mints in silver and copper.

He was succeeded in Drangiana and Arachosia by Ortaghnes, and in Gandhara by his nephew Abdagases I.[2][3]

Etymology

[edit]The name of Gondophares was not a personal name, but an epithet that is the Middle Iranian version of the Old Iranian vindafarna ("May he find glory"), which was also the name of one of the six nobles that helped the Achaemenid king of kings (shahanshah) Darius the Great (r. 522 BCE – 486 BCE) to seize the throne.[4][5] In old Armenian, it is "Gastaphar". “Gundaparnah” was apparently the Eastern Iranian form of the name.[6]

Ernst Herzfeld claims his name is perpetuated in the name of the Afghan city Kandahar, which he founded under the name Gundopharron.[7]

Background

[edit]

Gondophares was a member of the House of Suren, one of the most esteemed families in Arsacid Iran, that not only had the hereditary right to lead the royal military, but also to place the crown on the Parthian king at the coronation.[4] In c. 129 BC, the eastern portions of the Parthian Empire, primarily Drangiana, was invaded by nomadic peoples, mainly by the Eastern Iranian Saka (Indo-Scythians) and the Indo-European Yuezhi, thus giving the rise to the name of the province of Sakastan ("land of the Saka").[8][9]

As a result of these invasions, the Suren family was given control of Sakastan in order to defend the empire from further nomad incursions; the Surenids not only managed to repel the Indo-Scythians, but also eventually invade and seize their lands in Arachosia and Punjab, thus resulting in the establishment of the Indo-Parthian Kingdom.[4]

Rule

[edit]

The Romans moved Vonones I to Cilicia, where he was killed the following year after attempting to flee.[10] His death and the now unchallenged dominance of Artabanus split the Parthian nobility, since not all of them supported a new branch of the Arsacid family taking over the empire.[11] In 19/20, Gondophares declared himself king of the Parthian provinces of Drangiana and Arachosia, thus establishing the Indo-Parthian Kingdom.[12][11] He assumed the titles of "Great King of Kings" and "Autokrator", demonstrating his new-found independence.[11] Nevertheless, Artabanus and Gondophares most likely reached an agreement that the Indo-Parthians would not intervene in the affairs of the Arsacids.[12]

He was succeeded in Drangiana and Arachosia by Ortaghnes, and in Gandhara by his nephew Abdagases I.[2][3]

References

[edit]- ^ Rezakhani 2017, p. 35.

- ^ a b Rezakhani 2017, p. 37.

- ^ a b Gazerani 2015, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Bivar 2002, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Gazerani 2015, p. 23.

- ^ Mary Boyce and Frantz Genet, A History of Zoroastrianism, Leiden, Brill, 1991, pp.447–456, n.431.

- ^ Ernst Herzfeld, Archaeological History of Iran, London, Oxford University Press for the British Academy, 1935, p.63.

- ^ Frye 1984, p. 193.

- ^ Bosworth 1997, pp. 681–685.

- ^ Schippmann 1986, pp. 647–650.

- ^ a b c Olbrycht 2016, p. 24.

- ^ a b Olbrycht 2012, p. 216.

Sources

[edit]- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1997). "Sīstān". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 681–685. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Schmitt, R. (1995). "DRANGIANA". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5. pp. 534–537.

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2016). "Dynastic Connections in the Arsacid Empire and the Origins of the House of Sāsān". In Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Pendleton, Elizabeth J.; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj (eds.). The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion. Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781785702082.

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. pp. 1–411. ISBN 9783406093975.

- Gazerani, Saghi (2015). The Sistani Cycle of Epics and Iran's National History: On the Margins of Historiography. BRILL. pp. 1–250. ISBN 9789004282964.

- Bivar, A. D. H. (2002). "GONDOPHARES". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XI, Fasc. 2. pp. 135–136.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 9781474400305.