User:Herbert Acree/sandbox

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (March 2011) |

In mathematics, Buffon's needle problem is a question first posed in the 18th century by Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon:

- Suppose we have a floor made of parallel strips of wood, each the same width, and we drop a needle onto the floor. What is the probability that the needle will lie across a line between two strips?

Buffon's needle was the earliest problem in geometric probability to be solved; it can be solved using integral geometry. The solution, in the case where the needle length is not greater than the width of the strips, can be used to design a Monte Carlo method for approximating the number π.

Solution

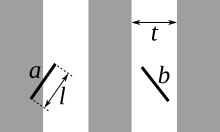

[edit]The problem in more mathematical terms is: Given a needle of length dropped on a plane ruled with parallel lines t units apart, what is the probability that the needle will cross a line?

Let x be the distance from the center of the needle to the closest line, let θ be the acute angle between the needle and the lines.

The uniform probability density function of x between 0 and t /2 is

The uniform probability density function of θ between 0 and π/2 is

The two random variables, x and θ, are independent, so the joint probability density function is the product

The needle crosses a line if

Now there are two cases.

Case 1: Short needle

[edit]| This user page may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: the text in the gif should be directly on the wikitext, not in the gif. Please help improve this user page if you can; the talk page may contain suggestions. |

Suppose .

Integrating the joint probability density function gives the probability that the needle will cross a line:

A particularly nice argument for this result can alternatively be given using "Buffon's noodle".

Case 2: Long needle

[edit]Suppose . In this case, integrating the joint probability density function, we obtain:

where is the minimum between and .

Thus, performing the above integration, we see that, when , the probability that the needle will cross a line is

or

In the second expression, the first term represents the probability of the angle of the needle being such that it will always cross at least one line. The right term represents the probability that, the needle falls at an angle where its position matters, and it crosses the line.

Using elementary calculus

[edit]The following solution for the "short needle" case, while equivalent to the one above, has a more visual flavor, and avoids iterated integrals.

We can calculate the probability as the product of 2 probabilities: , where is the probability that the center of the needle falls close enough to a line for the needle to possibly cross it, and is the probability that the needle actually crosses the line, given that the center is within reach.

Looking at the illustration in the above section, it is apparent that the needle can cross a line if the center of the needle is within units of either side of the strip. Adding from both sides and dividing by the whole width , we obtain

Now, we assume that the center is within reach of the edge of the strip, and calculate . To simplify the calculation, we can assume that .

Let x and θ be as in the illustration in this section. Placing a needle's center at x, the needle will cross the vertical axis if it falls within a range of 2θ radians, out of π radians of possible orientations. This represents the gray area to the left of x in the figure. For a fixed x, we can express θ as a function of x: . Now we can let x move from 0 to 1, and integrate:

Multiplying both results, we obtain , as above.

There is an even more elegant and simple method of calculating the "short needle case". The end of the needle farthest away from any one of the two lines bordering its region must be located within a horizontal (perpendicular to the bordering lines) distance of (where is the angle between the needle and the horizontal) from this line in order for the needle to cross it. The farthest this end of the needle can move away from this line horizontally in its region is . The probability that the farthest end of the needle is located no more than a distance away from the line (and thus that the needle crosses the line) out of the total distance it can move in its region for is given by

, as above.

Estimating π

[edit]In the first, simpler case above, the formula obtained for the probability can be rearranged to: . Thus, if we conduct an experiment to estimate , we will also have an estimate for π.

Suppose we drop n needles and find that h of those needles are crossing lines, so is approximated by the fraction . This leads to the formula:

Folklore

[edit]Two "facts" about the experimental determination of pi

Buffon did not estmate

[edit]Quoted experimental results are too good

[edit]Historical Experiments

[edit]185o, Wolf's Experiment

[edit]1855, H. Ambrose Smith's Experiment

[edit]Smith, H. Ambrose. “Popular Illustrations of the Doctrine of Probabilities [Nov 2, 1855].” Transactions of the Aberdeen Philosophical Society 1 (1884): xxxvi. http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?q1=ambrose;id=mdp.39015039330363;view=image;seq=42;start=1;sz=10;page=root;num=xxxvi;size=100;orient=0.

———. “Quadrature of the Circle.” The Athenaeum, no. 1470 (December 29, 1855): 1534. books.google.com/books?id=UYtUAAAAcAAJ.

———. “Quadrature of the Circle.” The Engineer 1 (1856): 19. http://books.google.com/books?id=v8NEAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA13&dq=%22Ambrose+Smith%22+aberdeen+lecture&hl=en&sa=X&ei=_qPpU7SUAo31oASLiYCYCQ&ved=0CB0Q6AEwADgU#v=onepage&q&f=false.

De Morgan, Augustus. A Budget of Paradoxes. Longman, Green, and Company, 1872. http://books.google.com/books?id=zvXv-oZ5TEQC.

1864, Fox's Experiment

[edit]1901, Lazzarini's Experiment

[edit]In 1901, Italian mathematician Mario Lazzarini performed the Buffon's needle experiment. Tossing a needle 3408 times, he obtained the well-known estimate 355/113 for π, which is a very accurate value, differing from π by no more than 3×10−7. This is an impressive result, but is something of a cheat, as follows.

Lazzarini chose needles whose length was 5/6 of the width of the strips of wood. In this case, the probability that the needles will cross the lines is . Thus if one were to drop n needles and get h crossings, one would estimate π as

- π ≈ 5/3 · n/h.

π is very nearly 355/113; in fact, there is no better rational approximation with fewer than 5 digits in the numerator and denominator. So if one had n and h such that:

- 355/113 = 5/3 · n/h

or equivalently,

- h = 113n/213

one would derive an unexpectedly accurate approximation to π, simply because the fraction 355/113 happens to be so close to the correct value. But this is easily arranged. To do this, one should pick n as a multiple of 213, because then 113n/213 is an integer; one then drops n needles, and hopes for exactly h = 113n/213 successes.

If one drops 213 needles and happens to get 113 successes, then one can triumphantly report an estimate of π accurate to six decimal places. If not, one can just do 213 more trials and hope for a total of 226 successes; if not, just repeat as necessary. Lazzarini performed 3408 = 213 · 16 trials, making it seem likely that this is the strategy he used to obtain his "estimate".

1901, Reina's Experiment

[edit]Summary of Experiments

[edit]The table below summarizes the various experimental results.

| Year | Author and Reference | # of Casts | # Of Hits | Delta(PI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | Wolf | 0.8 | 5000 | 2532 | 3.1596 | 0.0012 |

| 1855 | Smith | 0.6 | 3204 | 128.5 | 3.1553 | ).0026 |

| 1860 | DeMorgan | 1 | 600 | 382.5 | 3.137 | 0.0082 |

| 1864 | Fox | 0.75 | 1030 | 489 | 3.1595 | 0.0065 |

| 1901 | Lazzerini | 0.83 | 3408 | 1808 | 3.1415929 | 0.0017 |

| 1925 | Reina | 0.5419 | 2520 | 859 | 3.11795 | 0.0037 |

References

[edit]Additional Reading

[edit]- Badger, Lee (April 1994). "Lazzarini's Lucky Approximation of π". Mathematics Magazine. 67 (2). Mathematical Association of America: 83–91. doi:10.2307/2690682. JSTOR 2690682.

- Ramaley, J. F. (October 1969). "Buffon's Noodle Problem". The American Mathematical Monthly. 76 (8). Mathematical Association of America: 916–918. doi:10.2307/2317945. JSTOR 2317945.

- Mathai, A. M. (1999). An Introduction to Geometrical Probability. Newark: Gordon & Breach. p. 5. ISBN 978-90-5699-681-9.

- Dell, Zachary; Franklin, Scott V. (September 2009). "The Buffon-Laplace needle problem in three dimensions". Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment. 09 (9): 010. Bibcode:2009JSMTE..09..010D. doi:10.1088/1742-5468/2009/09/P09010.

- Schroeder, L. (1974). "Buffon's needle problem: An exciting application of many mathematical concepts". Mathematics Teacher, 67 (2), 183–6.

External links

[edit]- Buffon's Needle at cut-the-knot

- Math Surprises: Buffon's Noodle at cut-the-knot

- MSTE: Buffon's Needle

- Buffon's Needle Java Applet

- Estimating PI Visualization (Flash)

- Buffon's needle: fun and fundamentals (presentation) at slideshare

- Animations for the Simulation of Buffon's Needle by Yihui Xie using the R package animation

- 3D Physical Animation Java Applet by Jeffrey Ventrella

- Padilla, Tony. "∏ Pi and Buffon's Needle". Numberphile. Brady Haran.

Category:Applied probability Category:Integral geometry Category:Named probability problems