User:Fuse809/sandbox3

Note: Bold typeface is used to put emphasis on key terms. To make it easier to navigate this page I have hidden the tables as they are massive. When I start talking about how common each cancer is amongst the different races I am referring to the country of origin of the affected. For instance, a white Australian would in this system be called European, likewise a white American would be called European and an African American would be an African.

Blood cancers are among the most common forms of cancers with around 31 Australians diagnosed with one per day (or around 11,300 diagnosed per year) and they include: lymphomas, leukaemias and multiple myeloma (MM).[1] Many are very treatable if caught early, although, as always there's always the odd exception and, of course, the later it's caught the worse the outcome. Lymphomas are cancers of the cells (lymphocytes; the chief cells of adaptive immune system) found in lymphatic system including lymph nodes, spleen, bone marrow (the centre of bones where blood cells are created), etc. Lymphomas can be broken up into two major categories, Hodgkin lymphoma (formerly known as Hodgkin's disease or HL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Leukaemias can be broken up into two main categories: acute and chronic. The distinction is that acute leukaemias are more rapidly progressing than their chronic counterparts. They are the most common variety in children. Leukaemias can also be broken up into a further two major categories: lymphoblastic (or lymphoid/lymphocytic) and myeloid (or myelogenous) types in most cases. Lymphoblastic varieties arise from lymphoblasts which are produced in the bone marrow and mature (i.e. develop into) into lymphocytes. Myeloid leukaemia subtypes arise from myeloid cells which are precursors to myelocytes, a type of white blood cell which make up the innate immune system. Multiple myeloma is a cancer of the plasma cells (mature B-lymphocytes that produce antibodies to defend our body from past invaders).

Now I understand some of us don't want to read about the drugs and just get down to the bottom line and the basics of this article. Because of this I have created a table on the drugs and how they work so you can refer back to them if you want more details.

Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting

[edit]Before I go any further I should mention that oncologists (cancer docs) can be rather effective at helping cancer patients cope with the side effects of chemotherapy, including emesis [vomiting] and as part of this they treat patients with antiemetic [nausea and vomiting-inhibiting and -preventing] drugs usually before they're subjected to highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Such drugs include aprepitant (EMEND; very expensive at ~$40 AUD/pill, covered by the PBS as a treatment for Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting [CINV], however. It works by antagonising (blocking) the neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptor in the chemoreceptor trigger zone [CTZ], a part of the brain that contains a heap of chemoreceptors which are receptors that respond to certain chemicals, mostly toxic chemicals, and, in response to this sort of stimuli, activates the gag reflex and hence induces nausea and vomiting[2]), ondansetron (ZOFRAN; blocks the serotonin 5-HT3 receptors found in the CTZ and digestive tract [specifically on the vagus nerve (a large nerve that goes from the brain down through the torso into the digestive tract) for the most part][2]) and dexamethasone (another corticosteroid; much more potent than other corticosteroids. It assists antiemetic drugs in suppressing emesis but also stimulates appetite).[3]

Note: All estimates as to the incidence of nausea and vomiting as side effects of chemotherapy assume that the patient hasn't received the preventative regimen listen listed in this section.

Acronyms & Other terms

[edit]Definitions

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Drugs used in the management of blood cancers

[edit]Note: Unless otherwise specified Very common means that the side effect in question occurs in 10% or more of patients treated with said drug. Common means that the side effect occurs in 1-10% of patients treated with said drug. Uncommon means that the side effect occurs in 0.1-1% of patients treated with the drug. Rare means that the side effect occurs in <0.1% patients treated with the drug.

Antineoplastics

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lymphomas

[edit]Hodgkin lymphoma

[edit]HL is usually very treatable with a 5-year survival rate of around 90%.[26] Australians have a one in four-hundred and seventy-nine (1/479) chance of developing HL by the age of 85.[27] Around 300 Australians are diagnosed with HL per year.[27] I should probably explain the different staging of HL. Stage I HLs are limited to a single lymph node. Stage II HLs are limited to multiple lymph nodes on one side of the diaphragm (a sheet of muscle at the bottom of the lungs. Stage III HLs are limited to multiple lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm. Stage IV HLs have spread to extranodal (i.e. non-lymph node) organs as well as numerous lymph nodes. Stage I and Stage II HLs have a 5-year survival rate of 90%. Stage III HLs have a 5-year survival rate of 84%. Stage IV HLs have a 5-year survival rate of 65%. Notable sufferers of HL include Paul Allen, cofounder of Microsoft, and Richard Harris the actor that portrayed Albus Dumbledore in the first two Harry Potter films. The treatment for HL is mostly radiotherapy and chemotherapy.[26]

The usual initial symptoms of HL include:

- A painless swollen lymph gland in your neck, groin or armpit

- Unexplained fevers

- Night sweats

- Weight loss

- Tiredness

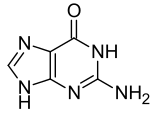

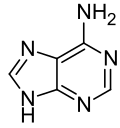

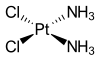

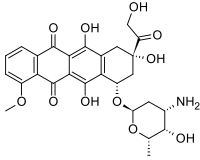

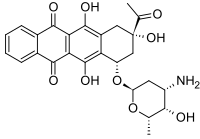

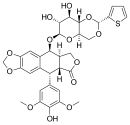

Chemotherapeutic induction regimens (i.e. regimens designed to induce a remission; only one at a time is tried, however) for HL include: MOPP, ABVD, Stanford V and BEACOPP. MOPP stands for mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisone. ABVD stands for adriamycin (this is a brand name used in the US; the generic name is doxorubicin), bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine. Stanford V consists of doxorubicin, vinblastine, mustard (mustard gas analogues such as cyclophosphamide, mechlorethamine or ifosfamide), bleomycin, vincristine, etoposide and prednisone. BEACOPP stands for bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisone.[28]

Salvage chemotherapy (which is for cases where induction chemotherapy fails or if the patient experiences a reoccurance) in HL usually consists of (one of) the following chemotherapy regimens: ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide), DHAP (cisplatin, cytarabine and prednisone) or ESHAP (etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, cisplatin).[28]

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

[edit]NHL is usually rather treatable too and is more than 14 times more common than HL, although in kids both HL and NHL are roughly as common as each other.[27] NHL makes up around 4% of cancer diagnoses in the US and accounts for around 4,300 cancer diagnoses in Australia each year.[27] Overall Australian individuals have a one in forty-two (1/42) chance of developing NHL by the age of 85.[27] Although it does heavily depend on the specific subtype as NHL consists of a whole set of different subtypes. Your odds of developing NHL increase as you get older and it most common affects those aged 65 years or older, although it can affect children and adolescents. The 5-year survival rate of NHL (taken as an average of all the different subtypes in the frequency at which they naturally occur) is around 71%. They have a number of different risk factors, including chronic inflammation (such as due to autoimmune conditions or unresolved infections), chromosomal abnormalities (Down's syndrome is probably the most notable chromosomal abnormality, although it's not one that's specifically associated with any NHL subtype), environmental factors (e.g. exposure to carcinogens like arsenic, fuel oil, tobacco smoke, etc.), immunodeficiency states (weak immune system caused by e.g. HIV infection), Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV; causative agent of Infectious Mononucleosis [Glandular Fever]) and Human T-cell lymphotropic virus [HTLV] infections. Subtypes of NHL include Burkitt's lymphoma (BL; I know of [although I didn't know them directly] someone that's died of this cancer. It's highly associated with EBV infections. More common in kids from central Africa or those with HIV infections), high-grade lymphoblastic lymphoma (HGLL), small noncleaved lymphoma (SNCL; the last two lymphomas are more common in kids), primary mediastinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (more common in females than males; this is the most common form of NHL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), anaplastic large cell lymphomas, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, follicular lymphomas (FL), small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma, T-cell lymphomas (TCL; specifically associated with the HTLV virus. This virus is spread via contact with an infected person's fluids, usually sexual contact. It is significantly more common in Japan than in other developed countries like Australia. It is also found in the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan African countries, South America and certain Iranian Jewish communities. HTLV is closely associated with the HIV virus), marginal zone lymphomas (MZL) and various others.[29]

The usual initial symptoms of NHL include:[27]

- Painless swelling of a lymph node in the neck, armpit or groin

- Unexplained and regular fevers

- Excessive sweating, especially at night

- Itchy skin

- Unintentional weight loss

- Tiredness

- Lethargy

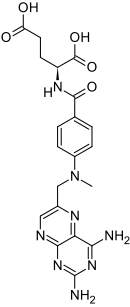

NHL is usually treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy (which is most frequently reserved for cases of indolent [non-aggressive] cancers that have not yet metastasised [spread]), although surgery may be attempted in select cases of non-metastatic lymphomas, especially gastrointestinal lymphomas such as MALT lymphoma.[30] NHL chemotherapy regimens vary greatly according to the specific subtype if NHL and the degree of metastasis. Aggressive (fast-growing), yet non-metastatic NHL is usually treated with the chemotherapy regimen CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone). CHOP is also used to treat metastatic indolent NHL. Metastatic aggressive NHL is usually treated with one of the following regimens: [30]

- CHOP

- ProMACE-CytaBOM (Prednisone, methotrexate , leucovorin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and etoposide)

- m-BACOD (Methotrexate, bleomycin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dexamethasone)

- MACOP-B (Methotrexate-leucovorin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone and bleomycin)

- Hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine) plus rituximab

- Bendamustine and rituximab

Of these regimens CHOP is probably best tolerated in terms of side effects, but it also tends to be less effective than the others. TCLs tend to be more difficult to manage than other lymphomas with current drug treatments. TCLs (CTCLs) are usually treated with the following treatment regimens:[30]

- CHOP + etoposide or gemcitabine

- Pralatrexate

- Alemtuzumab

- Denileukin diftitox

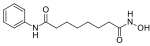

- Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, that is substances that inhibit the enzyme histone deacetylase (HDAC), which deacetylates (which corresponds to the deactivation of) histones, proteins involved in gene expression, that is the generation of proteins like receptors or enzymes from the genetic code (DNA) of the cell. Consequently these drugs increase the expression of certain genes while reducing the expression of others. HDAC inhibitors used to treat CTCL include vorinostat and romidepsin. These drugs are mostly limited to cutaneous (i.e. it affects the skin) TCL. Valproate (comes in various forms, there's a sodium salt [sodium valproate], a semisodium salt, valproate semisodium and an acid form), the anticonvulsant (anti-seizure), anti-migraine and mood-stabilising drug is also a HDAC inhibitor being investigated as a potential chemotherapeutic agent.

- Lenalidomide

- Bortezomib

When highly aggressive NHLs like Burkitt's lymphoma are treated there's the potential for tumour lysis syndrome (TLS) to be seen, which is basically when a large number of cancer cells die in a short period of time leading the build up of their intracellular products (that is substances that were found inside the cancer cells before they were killed) in the extracellular fluid (the fluid outside cells). This overwhelms the body's natural mechanisms that are designed to keep the concentration of the different constituents of the extracellular fluid at a safe level and can lead to kidney failure, hyperkalaemia and hyperphosphataemia.[31]

Leukaemias

[edit]Leukaemias and lymphomas are two of the most common childhood cancers. Although they are more common in the elderly than in children. The most common childhood cancer is actually acute lymphocytic leukaemia (ALL; accounts for around one-third of all childhood cancers),[32] closely followed by acute myeloid leukaemia (AML).[33] ALL has an fairly positive prognosis [outlook] with around 80% of kids with ALL achieving a cure and around 90% still alive at 5 years post-diagnosis.[32] AML has a less positive prognosis, although it greatly depends on the subtype of the cancer. Overall the 5-year survival rate of paediatric AML is around 45-60%.[33] In adults the prognosis tends to be less favourable, with ALL having a cure rate of around 25-40%.[34] Stats on adult AML are more difficult to come by. Chronic leukaemias tend to be incurable, but their survival times tend to be favourable. I actually had a distant relative with chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), whom I really learned died. Currently the median survival time for CML is over 5 years, with around 50-60% of patients still alive five years post-diagnosis.[35] Most patients chronic lymphoblastic leukaemia (CLL) live for 5-10 years after their diagnosis.[36] The 5-year survival rate of CLL in Australia is around 73%.[37] Every year around 2,600 Australians (based on the 2009 stat of 2,576) are diagnosed with leukaemia, the most common leukaemia was CLL with ~1,100 diagnosed annually.[37] After CLL comes AML at 900 diagnosed annually, ALL at 350 diagnosed annually and CML at 300 diagnosed annually.[37] In 2007 around 1,211 people died of leukaemia with AML accounting for most of these deaths (721 in 2007).[37] CLL came second in terms of deaths with 309 deaths in 2007 with CML at 92 deaths and ALL at 89 deaths.[37]

The different leukaemias tend to present initially with the same constellation of symptoms, including:[37]

- Tiredness

- Anaemia (pale complexion, weakness and breathlessness)

- Repeated infections

- Increased bruising and bleeding

- Bone pain

- Swollen, tender gums

- Skin rashes

- Headaches

- Vision problems

- Vomiting

- Enlarged lymph nodes

- Enlarged spleen which may cause abdominal discomfort

- Chest pains

The causes of leukaemia include exposure to radiation, carcinogens (e.g. benzene, tobacco smoke, alcohol [in excess] and arsenic) and HTLV infections. In most cases, however, no obvious cause can be found for the cancer. See many of these cancers occur in the elderly and it's just a danger of getting old. Acute leukaemias are usually treated with chemotherapy alone.[37]

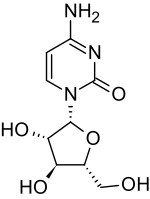

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

[edit]ALL is usually treated with chemotherapy. There are around five stages to treatment in ALL: induction (where the aim is to induce a remission), consolidation, interim maintenance (this stage is sometimes lumped in with maintenance), delayed intensification, and maintenance. The usual induction regimen in adults and children includes: vincristine, prednisone, an anthracycline (e.g. doxorubicin or daunorubicin) and cyclophosphamide and/or asparaginase.[38][39] After this comes the consolidation phase which is designed to get rid of any leukaemia cells hiding in the brain or testis and hence prevent any relapse.[38][39] The consolidation phase regimen usually consists of: cytarabine, cyclophosphamide and/or anthracycline (adult cases) and/or mercaptopurine.[38][39] After this comes interim maintenance which is when we're trying to keep back the cancer and prevent relapses while simultaneously giving the bone marrow the chance to recover from the damage done by the previous two stages of treatment.[38][39] The usual interim maintenance regimen consists of vincristine and intravenous methotrexate.[38][39] This treatment is continued for 4-8 weeks, after this comes the delayed intensification stage, information on which is not easy to obtain but I would guess that it would consist of the regimen used for induction.[38][39] It's designed to kill any remaining resistant leukaemia cells.[38][39] This stage appears to be mostly for children with ALL as I can't find any information regarding this stage in adults.[38][39] After this comes maintenance which can go on for indefinite period of time. Information on what's involved in this stage for adults is hard to come by but for kids it consists of three-monthly intrathecal, monthly vincristine treatments, steroid treatments, daily 6-MP and weekly MTX.[38][39] Sometimes radiotherapy of the head might be tried if it spreads there (sometimes it likes to hide out [away from the drugs that can't usually penetrate the BBB] in the brain and spinal cord).[39] It may also be used to completely destroy the bone marrow so that a bone marrow transplant can be performed.[38]

Acute myeloid leukaemia

[edit]AML is usually treated with chemotherapy alone.[40] Chemotherapy regimens used to treat AML include: "3 and 7" which consists 3 days of a 15-30 minute infusion of an anthracycline like doxorubicin, daunorubicin or idarubicin or an anthracenedione (mitoxantrone; works by inhibiting topoisomerase II) and 7 days of 24-hr daily infusions of cytarabine.[40] This sort of regimen achieves remissions in around 50% of patients with a single course and a further 10-15% achieve a remission with a second course of this regimen.[40]

Acute promyelocytic leukaemia

[edit]One subtype of AML, acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) has been reported to possess a 12-year disease-free survival rate of an estimated 69%.[41] This is particularly impressive because of the fact that the median age at diagnosis is 40, and the older the patient the worse the prognosis as a general rule of thumb (although other factors do come into the question, of course). APL is usually treated with anthracyclines, tretinoin and even a form of arsenic, arsenic trioxide. APL is the only malignancy (cancer) that tretinoin and arsenic trioxide is used to treat. Tretinoin is actually a form of vitamin A.

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

[edit]CLL is a form of leukaemia that predominantly affects the elderly (median age is about 72 years). It is more common in those of European ancestry (i.e. whites) than blacks (in this context as I'm reading this from an American source refers mostly to Africans). It is fairly uncommon in Asians, although it is possible this could be due to under-diagnosis in Asian countries. It is also more common in men than in women (men-to-women ratio of 1.7:1).[36] Some cases have a genetic component, in these cases the median age is less at 58 years.[36]

CLL is not usually considered curable, but because it is a slow-growing cancer, periods (most often months) of disease-free survival are usually possible with treatment and palliative care.[42] The only known cure is allogeneic stem cell transplantation (stem cell transplant from a genetically related donor), but this is not usually an option in the elderly, which are those that most commonly develop CLL.[42] Other treatments are surgery (spleen removal as it may harbour cancer cells sometimestimes), radiation and chemotherapy.[42]

Drug treatments for CLL include: chlorambucil, fludarabine, alemtuzumab and rituximab. There are a few monoclonal antibodies available in the US for this disease that aren't available in Australia. One such drug, obinutuzumab has been the subject of a recent clinical trial. In this trial obinutuzumab combined with chlorambucil (henceforth to be called OCH combo) produced superior responses to rituximab plus chlorambucil (RCH combo). Median progression-free survival times were 27 months for those on the OCH combo compared to just 15 months with RCH. Overall response rates were also higher (78% vs. 65%) for the OCH-treated patients. The number of patients for which no cancer could be detected in the blood was also higher in the patients treated with OCH (37.7% vs. 3.3%). Likewise those for whom bone marrow biopsies failed to detect any cancer was also higher in those treated with OCH (19.5% vs. 2.6%).[43]

Hairy cell leukaemia

[edit]Hairy cell leukaemia (HCL) is a subtype of CLL that's limited to the B cells. The median age of patients at diagnosis is about 52 years. Male-to-female ratio is about 4-5:1. As with CLL it is less common in those of Asian and African ancestry. It tends to be more responsive to treatment than CLL in general. It is usually initially treated with an IV/SC injection of cladribine for 7 days (either a continuous infusion with cladribine or 2 hour IV/SC daily injections at a higher dose for 5 days).[44] If it relapses after this treatment regimen rituximab or interferon alfa 2b may be used.[44][45]

Chronic myeloid leukaemia

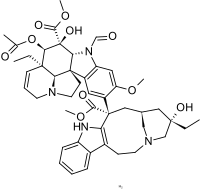

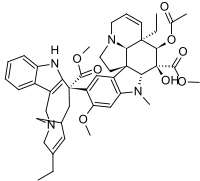

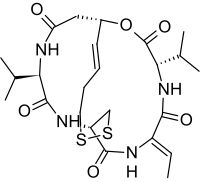

[edit]Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) tends to be incurable without a bone marrow transplant (where they destroy the old marrow with radiation and drugs and take bone marrow from a close relative and give it to you) or stem cell transplant. Despite this chemotherapy does tend to prolong survival. As may surgery (namely the removal of the spleen). Current TGA-approved cytotoxic treatments include: busulfan and hydroxyurea. Other TGA-approved non-cytotoxic treatments include the tyrosine kinase inhibitors: dasatinib, imatinib and nilotinib and the cytokine product peginterferon alfa 2a.[46] In the US there are 3 additional drugs that are approved for the clinical treatment of CML, and they include the two tyrosine kianse inhibitors: bosutinib and ponatinib (which may possess the edge in certain cases of treatment-resistance). The other drug is a natural product, omacetaxine, which is a semisynthetic derivative of a compound derived from cephalotaxus harringtonii, a plant native to Japan and China. It works via a completely different mechanism to all other antineoplastics listed here and hence may be particularly effective in treatment-resistant cases of CML.[47]

Multiple myeloma

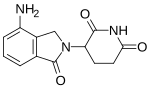

[edit]Multiple myeloma or MM for short is a cancer that arises from the plasma cells of the blood. These are the cells that produce antibodies and are mature B cells. It begins in the bone marrow and often the bone in which the bone marrow is found becomes severely damaged by the MM leading to an increased risk of bone fractures. It accounts for about 10% of all blood cancers. The 5-year survival rate is about 35%, and is more favourable in younger patients compared to their elderly counterparts. It is more common in Africans than Europeans. It is about half as common in Asians as opposed to Europeans. It is 1.4x more common in men than in women.[48] It is generally considered incurable.[48] TGA-approved cytotoxic antineoplastics used to treat MM include: cyclophosphamide, melphalan, doxorubicin, vincristine and bortezomib. Corticosteroids like prednisone and dexamethasone are often incoorporated into chemotherapy regimens for MM. Cytokine products used to treat MM include interferon alfa-2a and interferon alfa-2b. On top of this the two non-cytotoxic agents: thalidomide and lenalidomide.[49] Additionally bone marrow and stem cell transplants can be used to treat MM.[49] Radiotherapy of severely affected bones is sometimes attempted too.[49]

Notes

[edit]- ^ This information is based on QLD List of Approved Medicines. U - unrestricted. R - Restrictions apply. N - Non-PBS. RF - restriction flag. A - Authority required.

- ^ This classification is based on the AMH

- ^ The TGA only started a therapeutic goods registry in 1991 so drugs that were in clinical use prior to then may not have an accurate date as to when they were being used in Australia.

Reference List

[edit]- ^ "Blood Cancers". Leukaemia Foundation. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ a b Brunton, L; Chabner, B; Knollman, B (2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Schore, RJ; Williams, D (3 July 2012). Windle, ML; Coppes, MJ (ed.). "Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Velcade (bortezomib) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ^ Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Vidaza (azacitidine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "(bleomycin) dosing, indications, interactions, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Paraplatin (carboplatin) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "PRODUCT INFORMATION CARBOPLATIN INJECTION" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd. 23 December 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Leukeran (chlorambucil) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "Platinol, Platinol AQ (cisplatin), dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "PRODUCT INFORMATION LITAK® 2 mg/mL solution for injection" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Orphan Australia Pty. Ltd. 10 May 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "Cytoxan (cyclophosphamide) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Cytosar U, DepoCyt (cytarabine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "DTIC Dome (dacarbazine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "(doxorubicin) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Gemzar, (gemcitabine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ "(idarubicin) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "Mustargen, mechlorethamine hcl (mechlorethamine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Purinethol, 6Mercaptopurine (mercaptopurine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Trexall, Rheumatrex (methotrexate) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape reference. WebMD. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "(mitoxantrone) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "Istodax (romidepsin) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ "Zolinza (vorinostat) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ a b Lash, BW; Dessain, SK; Argiris, A; Kaklamani, V; Krishnan, K; Spears, JL; Talavera, F; Wasilewski, C (16 September 2013). Besa, EC (ed.). "Hodgkin Lymphoma". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f "Lymphoma". healthinsite. Cancer Council Australia. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ a b Lash, BW; Dessain, SK; Argiris, A; Kaklamani, V; Krishnan, K; Spears, JL; Talavera, F; Wasilewski, C (16 September 2013). Besa, EC (ed.). "Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vinjamaram, S; Estrada-Garcia, DA; Hernandez-Ilizaliturri, FJ; Krishnan, K; Rajdev, L; Sparano, JA; Talavera, F (24 June 2013). Besa, EC (ed.). "Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Vinjamaram, S; Estrada-Garcia, DA; Hernandez-Ilizaliturri, FJ; Krishnan, K; Rajdev, L; Sparano, JA; Talavera, F (24 June 2013). Besa, EC (ed.). "Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ikeda, AK; Jaishankar, D; Krishnan, K; Bergstrom, SK; Coppes, MJ; Grupp, SA; Sakamoto, SM; Sarnaik, AP; Schulman, P; Talavera, F; Windle, ML (10 October 2012). Harris, JE (ed.). "Tumor lysis syndrome". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kanwar, VS; Satake, N; Yoon, JM; Cripe, TP; Grupp, SA; Windle, ML (16 September 2013). Arceci, RJ (ed.). "Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Weinblatt, ME (10 July 2013). Sakamoto, KM; Windle, ML; Cripe, TP; Arceci, RJ (ed.). "Pediatric Acute Myelocytic Leukemia". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Seiter, K (16 January 2013). Sarkodee-Adoo, C; Talavera, F; Sacher, RA; Besa, EC (ed.). "Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Besa, EC; Buehler, B; Markman, M; Sacher, RA (20 December 2013). Krishnan, K (ed.). "Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Mir, MA; Liu, D; Patel, SC; Rasool, HJ; Perry, M; Sarkodee-Adoo, C; Talavera, F (23 December 2013). Besa, EC (ed.). "Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g "Leukaemia". healthinstitute. Cancer Council Australia. 18 January 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mir, MA; Liu, D; Patel, SC; Rasool, HJ; Perry, M; Sarkodee-Adoo, C; Talavera, F (23 December 2013). Besa, EC (ed.). "Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kanwar, VS; Satake, N; Yoon, JM; Cripe, TP; Grupp, SA; Windle, ML (16 September 2013). Arceci, RJ (ed.). "Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Seiter, K (9 March 2012). Sarkodee-Adoo, C; Talavera, F; Sacher, RA; Besa, EC (ed.). "Acute Myelogenous Leukemia Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Avvisati, G; Lo-Coco, F; Paoloni, FP; Petti, MC; Diverio, D; Vignetti, M; Latagliata, R; Specchia, G; Baccarani, M; Di Bona, E; Fioritoni, G; Marmont, F; Rambaldi, A; Di Raimondo, F; Kropp, MG; Pizzolo, G; Pogliani, EM; Rossi, G; Cantore, N; Nobile, F; Gabbas, A; Ferrara, F; Fazi, P; Amadori, S; Mandelli, F; GIMEMA, AIEOP, and EORTC Cooperative Groups (May 2011). "AIDA 0493 protocol for newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia: very long-term results and role of maintenance" (PDF). Blood. 117 (18): 4716–4725. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-08-302950. PMID 21385856.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Mir, MA; Liu, D; Patel, SC; Rasool, HJ; Perry, M; Sarkodee-Adoo, C; Talavera, F (23 December 2013). Besa, EC (ed.). "Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nelson, R (8 December 2013). "New Drug Combo Potentially 'Practice Changing' in CLL". Medscape News. WebMD. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ a b Kotiah, KS (28 October 2013). Anand, J; Braden, CD; Harris, JE (ed.). "Hairy Cell Leukemia Treatment Protocols". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Grever, MR (January 2010). "How I treat hairy cell leukemia". Blood. 115 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-06-195370. PMC 2803689. PMID 19843881.

- ^ Besa, EC; Buehler, B; Markman, M; Sacher, RA (27 December 2013). Krishnan, K (ed.). "Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Visani, G; Isidori, A (January 2014). "Resistant chronic myeloid leukemia beyond tyrosine-kinase inhibitor therapy: which role for omacetaxine?". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 15 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1517/14656566.2014.850491. PMID 24152096.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Seiter, K; Shah, D; Chansky, HA; Gellman, H; Grethlein, SJ; Krishnan, K; Rizvi, SS; Schmitz, MA; Talavera, F; Thomas, LM (23 December 2013). Besa, EC (ed.). "Multiple Myeloma". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Seiter, K; Shah, D; Chansky, HA; Gellman, H; Grethlein, SJ; Krishnan, K; Rizvi, SS; Schmitz, MA; Talavera, F; Thomas, LM (23 December 2013). Besa, EC (ed.). "Multiple Myeloma Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)