User:DPRK-USSR-PRC Cold War Timeline - drafting page/1

|

- Note: data unavailable for high profile visits to/from the DPRK before 1960.

Timeline of North Korea's relations with China and the Soviet Union: Contemporary scholarly observations of events (1960-1991)

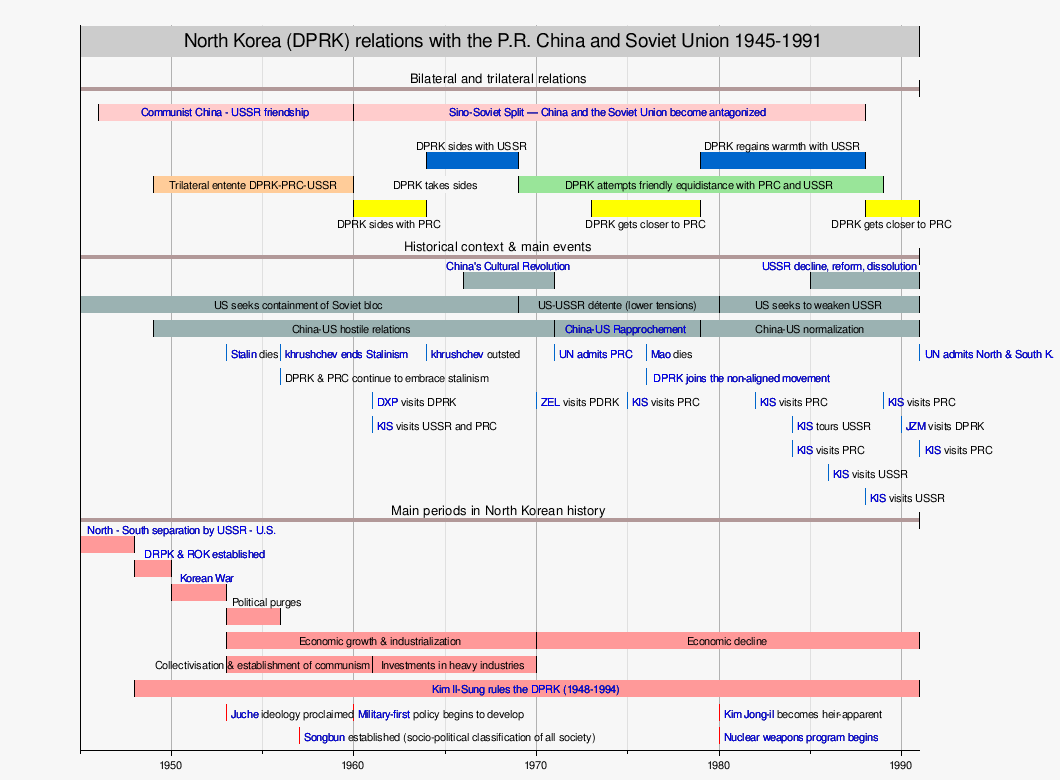

During the Cold War, North Korea's closest allies were the Soviet Union and P.R. China. These communist allies and neighbors were key to the origins of the country, and the struggles and survival of its regime. How North Korea managed and navigated its relations with its two key allies which it needed for its survival is an important historical question. Further, understanding how outside contemporary experts observed and interpreted those relations as they unfolded, illuminates how countries around the world based their strategic analysis and policy making for that region.

This timeline principally includes events as chronicled in contemporaneous academic journals and other serial academic publications that sought to provide quarterly or annual expert digests of developments in North Korea and/or its key allies. When those publications provided citations to other sources (mostly of news outlets), these are also cited in this article to provide insight into how the academic authors conducted their research and from which sources they drew information.

The secrecy and opacity of both North Korea and its communist neighbors meant that outside observers had very few, if any, independent sources. Often researchers resorted to heavily relying on the tightly controlled official state media and other forms of official communications from those three countries. Then, they tried to discern greater meaning from analyzing what was said, how it was said, what was omitted, any discrepancies between the press publications among the three countries, and by analyzing those in the broader economic and geopolitical context of the time.

In such a timeline of relations dependent on state media, visits by delegations, signing of treaties, and press editorials expressing fraternal support, feature prominently.

Methodology

[edit]This timeline series includes contemporary scholarly observation of events and developments between Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK; North Korea), and the People's Republic of China (PRC), and the Soviet Union (USSR). The timeline is extracted principally from academic journals, which also include contemporary scholarly analysis. Whenever possible the news sources cited by the journals are also referenced here.

Introduction: The division of the Korean peninsula and the Korean War

[edit]North Korea's relations with the Soviet Union and P.R. China were key to the origins of the country's and later developments.

Korea had for centuries been a high-ranking tributary state within the Imperial Chinese tributary system,[i] until in the late 18th century Japan began to assert greater control over the Korean peninsula, culminating in its annexation in 1910. It remained a colony of Japan, until Japan lost World War II in 1945.[ii][iii][iv][v]

Shortly before the end of WWII the Soviet Union declared war on Japan,[vi] and quickly moved to occupy the Korean peninsula. Soviet troops advanced rapidly, and the US government became anxious that the USSR might occupy the whole of Korea. The US government proposed, and the USSR quickly accepted, the 38th parallel as the dividing line between a Soviet occupation zone in the north and a US occupation zone in the south. The U.S. chose that parallel as it would place the capital Seoul under American control.[vii][iii]

In December 1945, at the Moscow Conference, the Soviet Union agreed to a US proposal for a United Nations-sanctioned trusteeship over Korea for up to five years in the lead-up to independence of the whole Korean peninsula.[viii][ix]

The USSR worked with existing People's Committees and local communist groups in the Northern Korean peninsula assigned as their trusteeship, recognizing in 1946 their authority to govern the territory. Since late 1945 Kim Il-Sung (who had fought the Japanese in Manchuria in the 1930s but had lived in the USSR and trained in the Red Army since 1941)[x] began to unify communist factions under his leadership, with the support - and tutelage - of the Soviets,[x] establishing the Workers' Party of North Korea (that later became Workers' Party of Korea, ruling Korea since 1949 to the present). Under Kim Il-Sung's leadership and Soviet support, the territory that would become North Korea quickly became fully communist.

Negotiations between the U.S. and USSR on holding unified elections in the peninsula, towards a unified and independent Korean peninsula broke down. In 1948 the U.S., with the U.N. approval, resorted to organizing elections on the southern territory under its control, quickly followed by the proclamation of the establishment Republic of Korea as the sole legitimate government of the entire peninsula. The Soviets quickly followed organizing their separate elections and the creation of the Democratic Peoples' Republic of Korea (with Kim Il-Sung as its official leader) and also claiming the same pan-Korean legitimacy.[xi][xii][xiii][xiv]

With the purpose of unifying the peninsula, Kim Il-Sung had repeatedly asked Joseph Stalin for approval and support to take the South by military force, with Stalin initially being opposed to the idea. In 1949 the Communist victory in China and the development of Soviet nuclear weapons made Stalin re-consider Kim's proposal. Kim also courted Mao Zedong for his support, and uppon apparently gaining such support, Stalin approved the invasion.[xv]

The Korean War went from 1950 to 1953. First the North (aided by the Soviet Union with advisors and material support, but not with troops) quickly took over most of the South, until the U.S. and other nations under the United Nations banner military intervened and quickly regained ground, at which point China directly intervened by surprise sending troops in support of the North, leading to a bloody stalemate until an armistice was signed in 1953. The armistice solidified the continued, and bitter, separation of North and South roughly along the 38th parallel.[xvi][xvii][xviii]

Timeline: 1960-1969 — The DPRK takes sides in the Sino-Soviet split

[edit]1960: The DPRK initially sides with the PRC

[edit]- 1960: Both the USSR and PRC agreed again to aid with North Korea's upcoming Seven-Year Plan.[1][2]

- The initial Soviet pledge was somewhat lower than earlier commitments, conforming to the steady downward trend in aid from the immediate postwar rehabilitation program.[1]

- China's contribution equivalent to 105 million US Dollars, was the largest loan offered to the DPRK in the postwar period, but the terms had shifted from earlier grants (in goods) to loans.[1][3]

- 1960-February-4: North Korea was invited to the Warsaw Treaty talks.[4][2]

- The summoning of the meeting of the Warsaw Treaty powers in Moscow on February 4 was surrounded with much mystery. At first it was stated on January 28 by Moscow Radio that the Communist Party and government leaders of the European satellites would be coming to Moscow for an agricultural conference on February 2. Delegations of observers from North Korea, Outer Mongolia, China, and Vietnam attended "by invitation."[4][2] A Chinese delegate also present made a speech praising and supporting the USSR's disarmament proposals, but also saying that the U.S. was not be trusted and that China needed time to strengthen its military to be able to counter America's "imperialist" actions in Korea and elsewhere in Asia.[2]

- 1960: China opposes to the USSR's proposed theory of peaceful coexistence. The Sino-Soviet split begins, and the PRC and USSR compete for allegiance of satellite Asian states, including the DPRK. The DPRK initially seems to lean in favor of the USSR.[5]

- In April China voiced for the first time its opposition to peaceful coexistence.[5]

- Russia called "dogmatic" and "left sectarian" those who saw as incompatible peaceful coexistence and disarmament with Marxism-Leninism. However, Russia refrained from explicitly stating who those were.[5][6]

- At the same time, General Li Chih-min, writing in the People's Daily on the 10th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean war (June 25) declared that "the modern revisionists" had been so scared by the "imperialist blackmail of nuclear war" that they exaggerated the destructiveness of such a war and begged the imperialists for peace at any price, thereby undermining "the militant spirit of the socialist countries." The dispute was carried to the Bucharest Congress in the last week of June, when Khrushchev rallied support from the European satellite parties for his policy, from which he said the Soviet Union "will not retreat a single step." However, the Chinese delegate, Peng Chen, still maintained that "so long as imperialism exists there will always be the danger of war."[5][6]

- Each side tried to win over other Communist Parties to its own point of view; in particular, the Soviet Union, challenged in its leadership of the Communist bloc by the Chinese criticism, circulated to other parties full texts of Khrushchev's speech at the Romanian Communist Party Congress at Bucharest in June. Almost all the European parties showed themselves willing to follow the Soviet line; the contest was rather for the allegiance of the Asian parties, and here too both the Mongolian People's Republic and North Korea inclined to the Soviet side.[6]

- 1960-June-22: The USSR and DPRK signed a treaty on trade and navigation.[2]

- 1960-July-27 - 30: North Korea and China among others attended as observers to the Soviet-led Council for Mutual Economic Aid in Budapest.[2]

- 1960-November-11: The DPRK issued a memorandum on "The Peaceful Unification of Korea", to which on December 7 the USSR issued a statement of support.[2]

- 1960-December-24: The DPRK and USSR signed an agreement for Soviet technical assistance.[2]

- 1961-1971: The USSR and China continued to supply military hardware to the DPRK at favorable price conditions.[7]

- According to a September 1973 report of the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency to the U.S. Congress, in the 1961-71 period the Soviet Union supplied North Korea with $505 million worth of military hardware, with the latter paying 50% or 60% of the list price.[7]

- China, on the other hand, provided $115 million worth of supersonic aircraft and naval ships either without charge or under a barter arrangement.[7][a]

- 1961-May:The military coup in South Korea of May 1961 seemed to have intensified Pyongyang's fears that the U.S. was only making time until an attempt was made to destroy the DPRK and the North Korean leadership apparently felt the need for military guarantees from both the USSR and PRC. [8][1][9]

- 1961-July-6: Kim Il-sung travelled to Moscow to sign a Treaty of Friendship and Mutual Aid.[8][1][9][10]

- The visit was from June 29 to July 10, with the treaty signed on the 6th.[10] The treaty was scheduled to be automatically renovated every 5 years,[11] with an initial period of 10 years.[10]

- On July 10 a joint communiqué announced two other agreements to provide further Soviet financial, technical, and industrial assistance.[10]

- The communiqué also stated that the Korean Workers Party acknowledged the Soviet communist party "as the universally recognized vanguard of the world Communist movement" and that both "condemned dogmatism, sectarism, and backsliding principles of Socialist internationalism"[10]

- 1961-July-11:Kim Il-sung travelled to Beijing to sign a Treaty of Friendship and Mutual Aid.[8][1][9] It was set to be valid indefinitely, [11] and closely resembled the agreements signed days before with the USSR.[10]

- 1961-September: Deng Xiaoping visited North Korea.[12]

- 1961-October: When Khrushchev attacked the Albanian leaders at the 22nd CPSU Congress and provoked an angry retort from Zhou Enlai, Kim and the DPRK delegation remained publicly silent.[8]

- 1962: By this point there were indications that Kim had already succeeded in purging the rival political factions (including the "Yenan", "indigenous", and "Moscow" factions), creating a monolithic political and media apparatus following and adulating him even with greater intensity that Mao in China.[13]

- 1962: The DPRK made great efforts to remain friendly with both the USSR and PRC as the Sino-Soviet split was unfolding, and struggled in avoiding aligning itself with one of the two powers.[13][1][14]

- The DPRK greatly depended on the aid from both countries, although there were indications that recently the Chinese support had been more generous.[13]

- The Korean Workers Party refused to criticize Albania or to follow the full de-Stalinization campaign proclaimed by Khrushchev, but at the same time, it continued to enthusiastically praise the Soviet Union and the CPSU, and to insist that its friendship with both the USSR and the PRC was unbreakable.

- 1962: On the Indian-Chinese border dispute, the DPRK displayed complete support of Beijing. On the same matter, Moscow displayed ambivalence.[13][15]

- 1962: The USSR's back down in the Cuban Missile Crisis gave the DPRK even more reason to doubt Moscow's resolve in a direct confrontation with the US.[8] Kim criticized Khrushchev's appeasement strategy.[13]

- The North Korean leadership also backed the PRC's aggressive policy as more likely to produce quick gains in Asia, Africa and Latin America.[8]

- 1962-February: The DPRK signed another trade agreement with the USSR.[16]

- 1962 - 1964: The DPRK ended up openly siding with China in the sino-soviet split. The DPRK's relations with the USSR deteriorated with the development of Soviet "revisionism”.[1]

- 1962-April: The emergence of Korean Communist nationalism within the KWP, was exemplified in an article published on the occasion of the 50th birthday of Kim Il-song, which stressed the establishment of Juche ideology by the KWP and mentioned neither Russia nor China.[17][18]

- 1962-63: The DPRK displayed renewed belligerency and aggressiveness. While Premier Khrushchev continued to stress the policy of coexistence, the fifth plenum of the fourth Central Committee of the KWP (December 10-14, 1962) "especially emphasized the need of arming the entire people, strengthening our defense power to that of an iron wall, and turning our entire country into an impregnable fortress."[14][b]

- In the field of foreign policy, North Korea had been striving to broaden its contacts with the non-Communist bloc while maintaining a precarious "neutralism" in the Sino-Soviet dispute.[14]

- 1963: Although North Korea renewed its treaties and agreements of mutual economic, scientific, and technical cooperation with the Soviet Union and the Eastern European satellite countries, it moved a step farther this year toward Communist China in the Sino-Soviet dispute.

- An editorial in Rodong Sinmun reiterated the necessity of maintaining unity within the socialist camp and criticized open attacks launched by some of the "fraternal parties" against China. The editorial stated that there was virtually no difference between attacking China and joining the anti-Chinese imperialist camp.[14][c] Further Rodong Sinmun editorials that year issued strong attacks against Tito's revisionism, as thinly veiled attacks against the USSR itself.[14][II][d][e]

- 1963-June: Choi Yong-kun (the chairman of the presidium of the People's Supreme Assembly) visited China, apparently generating much goodwill.[3][14][19]

- Choi visited China from June 5 to June 23. His appeals for a "decisive struggle against imperialism"[3] and "revisionism"[19] and his reminiscences about Sino-Korean cooperation in the Korean War were very well received.[3]

- On June 18, the North Korean press published the CCP's letter to the CPSU of June 14, and on June 23 a Sino-Korean joint statement declared that "it was absolutely impermissible one-sidedly to reduce the foreign-policy of socialist countries to peaceful-co-existence."[3][III]

- A joint statement of Choi and Chairman Liu Shaoqi declared that "both sides were completely identical in their stand and views."[f][14][IV]

- 1963-July: In the lead to a USSR-PRC summit, China republished texts denouncing the USSR, authored by foreign communist allies including the DPRK.[3]

- As Russia and China prepared to meet for bilateral talks (which began in Moscow on July 5) both sides seemed increasingly determined to make a stand on their well-known and very different positions. As before, the Chinese people were kept informed of foreign criticism in the dispute. While the Russians observed the truce on public polemics the Chinese press reported without comment news of Russia's infidelity-giving aid to India and moving closer to an agreement with the US on a nuclear test ban. This was supplemented by reprinting selected North Korean, North Vietnamese and Japanese Communist articles which supported the Chinese point of view. In contrast the USSR preferred to give the Chinese statements as little publicity as possible.[3]

- 1963-September-18: President Liu Shaoqi visited North Korea from September 18-27.[20]

- A communiqué issued at the end of the visit announced a "complete identity of views on all subjects discussed," including "important questions arising in the international Communist movement." North Korea still refrained from denouncing Khrushchev by name.[20]

- 1963: North Korea (together with North Vietnam), refrained from signing Moscow's nuclear test-ban treaty. This was the first major issue in the Sino-Soviet dispute on which these two countries had to choose between the USSR or PRC.[20]

- 1963-September: An academic publication in the USSR made a list of communist countries. The list did not include China, Albania and North Korea.[21][VI]

- 1964-March: A Romanian delegation, after visiting Beijing in an effort to mediate in the Sino-Soviet split, visited the DPRK, and the DPRK showed it had taken sides in favor of China over the discussion on where and when to hold a proposed general conference of Communist Parties.[22]

- 1963-October-14: The Sino-Korean Trade Protocol for 1964, signed in Pyongyang on October 14, envisaged a marked growth in trade.[21][23]

- 1964: China began to export an unspecified amount of oil to North Korea, under the protocol on mutual supply of goods signed the previous year.[23]

- 1964: In border demarcation negotiations between PRC and USSR, China mentioned how past USSR loans to China had been used to finance the Korean War.[24]

- China claimed that it was willing to take the "unequal treaties "as the basis for a frontier settlement", even though the USSR had stirred up trouble in the borderlands. During the negotiations, China pointed that Soviet aid and trade had certainly not been disinterested as the USSR claimed. Moreover, most of the Soviet loans had to be used to finance the Korean War.[24]

- 1964-August: China and North Korea boycott the USSR's international meeting.[25]

- The Chinese Communist Party reiterated its determination to boycott the preparatory meeting of the twenty-six Parties in a letter to the Soviet Communist Party. China was supported in its boycott by the Albanian, the North Korean, the North Vietnamese, the Indonesian and the Japanese Communist Parties.[25]

- On the issue of the international Communist meeting called by Khrushchev for December 15, Pyongyang issued a strong statement in September denying its legality. Pyongyang continued to issue pronouncements praising the accomplishments of Albania.[26]

1964: Tensions mount between China and the DPRK

[edit]- 1960's (early-mid): The consequences of taking sides in interallied disputes, regardless of North Korean motives for doing so, were sobering. The Soviet Union responded by terminating almost all economic and military aid to the DPRK.[1]

- This, along with inadequate Chinese compensation, led the North Korean leadership to question the wisdom of its policy. Implementation of the Seven-Year Plan slowed down. The new military program of intensified guerrilla activities against the South had also met with difficulties.[1]

- Pyongyang showed fears of becoming isolated in the communist world and started to consider a return to its previous policy of neutrality in the Sino-Soviet split. By 1965, the Soviet Union was also ready to resume cordial relations. Khrushchev's successors had concluded that the escalation of the war in Vietnam and the persistent Sino-Soviet disagreement required moves to restore Soviet credibility in Asia.[1]

- 1964-June: One of the important events in North Korean foreign affairs in 1964 year was the hosting of the "Asian Economic Seminar," held on June 17-23 in Pyongyang.[26][VII][g]

- 1964: Although the trade agreement with the Soviet Union was renewed this year and some Soviet technicians were sent to North Korea, the Korean Communists maintained their pro-Chinese stance in the current schism within the Communist camp.[26][IX][h]

- 1964-October: The removal of Nikita Khrushchev from power in the USSR, opens the door to improved relations between USSR and DPRK.[15]

- 1960's (mid): Tensions mounting during China's Cultural Revolution to the point that Red Guards put up wall posters in Peking calling Kim Il-Sung a "counter revolutionary revisionist "as well as a "millionaire, an aristocrat, and a leading bourgeois element in Korea."[27] As Soviet-North Korean relations improved throughout the latter half of the 1960s, Chinese-North Korean relations deteriorated accordingly.[15]

- 1964-December: USSR and DPRK signed a trade protocol for the sale of Soviet airliners.[28]

- 1965: The Soviet Union's stiffer attitude toward the United States since the beginning of regular air strikes on North Vietnam in February 1965 may have convinced the North Korean leadership that Khrushchev's policies of "peaceful coexistence" are undergoing re-evaluation.[8]

- 1965-February to May: Kosygin visited Pyongyang and offered the military aid agreement which was later announced in Moscow in May.[28][29][30]

- Soviet Premier Kosygin was cordially treated in his visit to Pyongyang in February in the spirit of "traditional friendship, "[i] and in May, Moscow agreed to help North Korea with additional military hardware.[31] For North Korean leadership, Moscow was of more help than Beijing in certain respects, however in the denouncement of "American imperialism" and in the admiration of Cubans in their fight against "American imperialism" at America's door-step, North Korea pursued a Beijing line.[29]

- 1965: Forced by South Korean participation in the war in Vietnam, North Korea committed itself to help North Vietnam with arms and equipment. It is in this sharing of the common enemy that North Korea had identified itself more closely with Communist China in the ideological dispute between Beijing and Moscow.[29]

- 1965-August: The Soviet Union sent Shelepin to Korea's liberation anniversary while the Chinese sent a low-level delegation.[28]

- 1965: The 15th anniversary of Communist China was celebrated with the attendance of international leaders including President Choe Yong-gon of North Korea.[32]

- 1965-November-19: China said UN should cancel resolutions condemning China and DPRK as aggressors in the Korean war.

- A People's Daily editorial restated China's demands for "thorough reorganization" of the U.N.: "Expelling the members of the Chiang Kai-shek clique from the UN and restoring to China its legitimate rights is an indispensable step for the United Nations to correct its mistakes and undergo a thorough reorganization. But it is far from enough to do this only. The United Nations must also resolutely condemn U.S. imperialism, the biggest aggressor of our time and cancel its slanderous resolution condemning China and the DPRK as aggressors and all its other erroneous resolutions. The UN Charter must be reviewed and revised by all countries of the world. Its members must include all independent countries to the exclusion of all the puppets of imperialism." [28][j]

- 1965-October: Korean delegates attended an International Red Cross Conference in Vienna which China boycotted.[28]

- 1965-November: Korea abstained from a vote in which Sino-Soviet lines were drawn at the World Trades Union Conference in Warsaw. [28]

- 1965-late: After Korea's three-year-old policy of solidarity with China, the recent accumulation of minor amity gestures between the DPRK and USSR, hinted to a change of policy in Korea, and suggested that the DPRK and the USSR had been edging closer together since Khrushchev's fall. These helped to change North Korea's international image from a satellite of Beijing to the would-be Romania of the East.[28]

- 1965-October-10: Kim Il-sung said he wanted to have an "independent and principled stand" between the two great communist powers. He also continued to remind the USSR that the Koreans had not yet forgotten their grievances against them and were not at all likely to exchange one big brother for another. [28]

- In a major speech on the 20th anniversary of the Korean Workers' Party on October 10, Kim made Romanian-like charges against Russian economic policies in Korea: "They opposed our party's line of socialist industrialization, the line of the construction of an independent national economy in particular, and they even brought economic pressure to bear upon us, inflicting tremendous losses upon our socialist construction."[28][k]

- Kim also made Chinese-like attacks on revisionist-capitulationism: "The biggest harm of modern revisionism lies in the fact that, scared by the nuclear blackmail of U.S. imperialism, it surrenders to it, gives up struggle against imperialism and compromises with it. (...) Revisionism still remains the main danger in the international communist movement today".[28]

- On December 6, an editorial in the North Korean Party paper, Rodong Sinmun, repeated Kim's warnings about modern revisionism which "emasculates revolutionary peoples."[28][l]

- 1965-December-14: China and North Korea signed a 1966 goods exchange protocol in Pyongyang.[28]

- 1966: During the Cultural Revolution, Chinese Red Guard posters charged North Korean "revisionist cadres" with extravagance and corruption and accused Kim himself of being a "millionaire, an aristocrat and a leading bourgeois element."[15]

- 1966: the KWP continued to consolidate its position of neutrality in the Sino-Soviet conflict.[34] The KWP, even if still wary of the CPSU, relations between the two party appeared to be improving.[34] As a result of the KWP's advocacy of united action in Vietnam and its militant stand on independence, relations between the KPW and CCP deteriorated.[34]

- 1966: the North Korean press published an explicit criticism of Chinese ideographs.[15]

- The DPRK said that Chinese characters symbolized linguistic backwardness and that the Korean people should be proud of their phonetic alphabet and should not waste time trying to learn the Chinese symbols.[15]

- 1966-January-3 to 15: At the Tri-continentnal conference of Havana, the USSR wanted to include the concept of peaceful coexistence in the leading resolutions of the conference. China and North Korea opposed it; the USSR was supported by a majority in its inclusion, but the pro-Chinese bloc succeeded in keeping them out from the general and political resolutions.[34][35]

- 1966-March: North Korea sent a high level delegation to the 23rd Party Congress of the CPSU which Beijing boycotted.[15]

- Choi Yong Kim attended the congress. In a speech there he said that "the Korean and Soviet peoples" were "linked by ties of friendship from the time of their joint struggle against Japanese imperialism", and expressed the desire to continue to strengthen relations and cooperation between the two countries.[34][n]

- The CPSU report published at its conclusion stated that it had "good fraternal relations" with a number of countries including the DPRK, but it did not list the PRC.[34][35]

- 1966-August-12: North Korea asserted its independence by a newspaper article criticizing in equal measure both Moscow and Beijing,[36][37] while also declaring the pursuit of a policy of self-reliance.[37][34]

- On August 12 the DPRK published a Rodong Sinmun editorial entitled "Let Us Defend Independence" that was widely interpreted as a "declaration of independence" from both Chinese[38] and Soviet influence[37]. This was consistent with the analysis of the recent editorial lines of Pravda and People's Daily, which showed throughout the year a gradual increase in Soviet news about North Korea combined with a decline in Chinese reportage. Most observers abroad, as well as some leading Korean analysts interpreted the doctrinal statement as a further indication of national differentiation within the Communist international system, as well as a correlate of the war in Vietnam and of the "cultural revolution" in Beijing.[38][37][o][X]

- The article rejected the universal applicability which the Chinese claim for Maoism: "No matter how good the guiding theory of the Party of a certain country may be, it cannot be applied to all parties because the requirements and situations of revolution differ in all countries." It rejected "big-nation chauvinism": "There are big parties and small parties but there can be no superior party or inferior party nor a party that gives guidance and a party that receives guidance." It praised the "just stand" of the Japanese Communist Party which, distressed by the cultural revolution, had recently been voicing disapproval of Beijing. It also urged for "joint action and a united front in the struggle against U.S. imperialism" (especially in support of North Vietnam). It also declared the pursuit of a self-reliance.[36][p]

- On August 12 the DPRK published a Rodong Sinmun editorial entitled "Let Us Defend Independence" that was widely interpreted as a "declaration of independence" from both Chinese[38] and Soviet influence[37]. This was consistent with the analysis of the recent editorial lines of Pravda and People's Daily, which showed throughout the year a gradual increase in Soviet news about North Korea combined with a decline in Chinese reportage. Most observers abroad, as well as some leading Korean analysts interpreted the doctrinal statement as a further indication of national differentiation within the Communist international system, as well as a correlate of the war in Vietnam and of the "cultural revolution" in Beijing.[38][37][o][X]

- 1966-October: The DPRK apparently purged Kim Ch'ang-man, a well-known leader of the pro-China Yenan faction. He was removed from his position as Vice Chairman of the Central Committee of the Korean Workers Party in October 1966. At that time, too, Nam Ii, Vice-Premier and equally well-known leader of the Soviet faction, was assigned to be Minister of Railroads. Nevertheless, he was allowed to retain the title of Vice-Premier, even though his major job became relatively unimportant. Nam Ii appeared at the opening ceremony of the Seventh Session of the 3rd Supreme People's Assembly on April 25, along with the members of the Presidium of the Politburo.[39]

- 1966-October-5 to 12: The KWP held a major conference of its central committee. By calling it a "conference" instead of a "congress" (the last congress having been held in 1961), the KWP did not have to invite foreign delegations, as a way to maintain its "neutralist" approach to the Sino-Soviet split.[34]

- Kim in a speech emphasized again the policy of self-reliance: "To build an independent national economy on the principle of self-reliance is a consistent line of our party (...) Complicated problems that have arisen within the socialist camp make imperative for us to cement further the foundations of the independent economy of the country" and "it is of paramount importance in our revolutionary struggle and construction work today to reorganize all work of socialist construction in line with the requirements of the prevailing situation, and in particular, to carry on the parallel building of the economy and defense so as to increase our defense capabilities (...) This will require lots of manpower and materials for national defense and will inevitably delay the economic development of our country in a certain measure".[34]

- 1966-November: Li Yung Ho, leading the KWP delegation to 5th Albanian Workers Party congress, made no direct mention of the USSR or PRC, but said "it is inadmissible for communist and workers' parties either to impose their will on another party or to submit to the course and policy of another party".[34][q]

- 1966-December: 1966 ended with the DPRK having stayed muted on the Chinese cultural revolution.[34]

- 1967: Apparently Kim Il-song had tightened his ruling oligarchy by removing both the Soviet and Chinese factions from the center of power.[r] On the other hand, he was desperately trying to build a strong wall by which he could stop the waves of the Red Guard Movement from China. As of that time, Rodong Sinmun had not carried a single article on the Red Guard Movement in China, although the danger of dogmatism had been mentioned several times. That North Korea still wanted to maintain cordial relations with China was evident in the Rodong Sinmun editorial titled "the aggressive friendship bound by blood."[39]

- 1967: China's Red Guards negatively affected foreign relations, including quarrels of varying magnitude with 32 countries, including North Korea. Zhou En-Lai reigned them in later.[40]

- Chinese diplomatic staff abroad, who felt bound to allay suspicions at home that they were living lives of luxury, carried out demonstrative and sometimes violent propaganda for Mao's cultural revolution. During September, however, the moderates in the Foreign Ministry strengthened their position; Red Guards were rebuked by Zhou En-lai, Chen Boda and Jiang Qing for attacking embassies and it was Yao Teng-shan's turn to be criticized by wall posters.[40]

- 1967: The most conspicuous development of 1967 in North Korea was the continuing détente with the Soviet Union and the visible deterioration in relations with Communist China. Since North Korea's declaration of the so-called "independence line"[37] in Communist international relations, its relationship with Communist China had deteriorated rapidly. The Chinese accused the Koreans of betraying their friendship with China and the revolutionary movement in Asia. It was not unusual to see Beijing wall posters calling for the removal of Kim Il-sung, and even reporting in February that Kim and his lieutenant Kim Kwang-hyop had been arrested by the army.[s][t][u][v][w] In return, the North Korean Central News Service bitterly criticized Chinese intervention in the internal affairs of North Korea.[39]

- 1967: North Korea pursued a rapprochement with the Soviet Union in part driven by the impending necessity to modernize its armed forces with new weapons as well as to seek economic aid to complete the Seven Year Economic Plan.[39][41]

- The fact that North Korea was spending almost one third of its total budget on military defense was significant. The leaders of North Korea apparently believed that another Korean war was near, due to the escalation of the Vietnamese war. Rodong Sinmun's editorials had become increasingly bellicose. Although North Korea normalized its relationship with the Soviet Union because of economic and military necessity, its ideology still remained closer to that of the Chinese. Recent speeches of Kim Il-sung reveal that he still opposed peaceful coexistence; he still did not believe that the nature of capitalism had changed; he still criticized both modern revisionism and dogmatism; and he still supported wars of national liberation. Thus he called for the unity of the socialist camp and the solidarity of international Communism.[x] His cry for an "all out fight against American imperialism" had created tensions and concerns in Korea.[39]

- In 1967 not a single anti-Soviet article appeared in Rodong Sinmun.[39]

- 1967-February: China's Red Guard attacked Kim Il-sung as a "fat revisionist" and "Khrushchev's disciple," accusing him of sabotaging the struggle in Vietnam and slandering the cultural revolution.[42]

- Korea did not reply directly but late in February, Korean representatives in Cuba, India and elsewhere issued statements denying the coup rumors and demanding a cessation of the "calumnies " and "defamation" being disseminated in China.[42]

- 1967-February - March: North Korea's détente with the Soviet Union rapidly accelerated, with North Korea sending an important mission headed by First Vice-Premier Kim Il to Moscow, apparently to seek more economic and military assistance.[39][42]

- The mission stayed in Moscow more than two weeks and signed agreements for economic and cultural as well as military assistance. Although the content of the agreements were unknown, the Soviet Union was then positively supporting North Korea's plan "to develop industry and defense simultaneously."[39][y][42]

- 1967-May: The Soviet Union appointed a new ambassador to the DPRK and sent Vice-Premier V. N. Novikov to Pyongyang.[39]

- 1967-May - October: In July a Korean-Soviet scientific exchange program for 1967 was agreed upon, and another agreement followed in October to establish an economic and scientific technical consultative commission to accelerate the cooperation between the two countries.[39][y]

- 1967-September: The DPRK ambassador to China (Hyon Chun-Kuk) leaves China in September due to the strained relations caused by the Cultural Revolution. China's ambassador to the DPRK, Chiao Jo-yu, had also returned to China in mid-1967.[43]

- 1967-68: More purges of political leaders in the DPRK took place, being replaced by more "hawkish" ones. The purge may have been caused due to differences in the policies of the individuals toward the South Korean revolution and toward Communist China.[44]

- Rumors and absences from the public scene indicated that the purge may have included: Pak-Kum-Chol and Yi Hyo-sun; third and fourth in rank, respectively in, the Presidium of the Korean Worker's Party. Also, Kim To-man (Secretary General of the Supreme People's Assembly), Yim Ch'un-ch'u (member of the Party Standing Committee), Ko Hyok (Vice-Premier in the cabinet), and Ho Sok-son (chief of the Party Cultural Bureau).[44]

- 1968: Kim seemed to go back on its old thesis of peaceful Korean unification, and designated the year 1968 as one of preparation for war, stressing slogans such as "the fortification of the whole country," "armament of all people," "the modernization of the army," and "upgrading the quality of the people's army [Kindae ii Kanbu Hwa].[z][aa][ab][ac][44]

- He apparently felt that there was a real threat of another Korean War and thought that the nation could exist only through its own strength since Russia and Communist China were seen as no longer reliable.[44]

- In order to implement those slogans, the North Korean defense budget was raised to 1,617,330,000 won (approximately $652 million, $172 million more than the preceding year), which constituted 30.9% of the 1968 national budget. The DPRK regime also intensified its own brand of "cultural revolution" in order to prepare for the coming war. Kim had increasingly stressed the value of "thought reform" on a national scale, believing that ideologically unprepared people could not win the war. During that movement, Kim was idolized as a "true revolutionary," and people were forced to study his life and teachings. The "cult of personality" was practiced in its highest form to date in North Korea.[44]

- 1968:In the realm of international relations, Kim maintained his "independent line" policy and continued to criticize both the "revisionism" of the Soviets and the "dogmatism" of the Chinese. He warned against "big power chauvinism" and maintained that the international Communist movement should be based on the principles of equality, sovereignty, mutual respect, and non-interference in another country's internal affairs. Kim had retained close ties with North Vietnam, Cuba, and the Communist party in Japan, all of which supported this "independent line." On the other hand, North Korea did not send a delegation to the preliminary conference for world Communist parties held in Budapest, and Kim has already hinted that the DPRK will boycott next year's Moscow meeting. North Korea severely criticized the liberalization movement in Czechoslovakia, but did not openly support the Russian intervention there.[44][ad]

- 1968: The relationship between the Soviet Union and North Korea had continually improved since 1965, while relations with China had slowly deteriorated. The USSR sent Vice-Premier Polyansky to congratulate the DPRK on its 20th anniversary; China, Albania, and Czechoslovakia sent no one (although Chou En-lai did send a congratulatory telegram).[44]

- The Chinese Red Guards were still accusing Kim Il-sung of being a "revisionist and anti-revolutionary."[ae] In turn, Kim had systematically purged all the pro-Chinese elements in his regime, while the pro-Soviet members had been elevated in stature. In the new cabinet, for instance, Nam II, a prominent pro-Soviet leader, was promoted from the Railroad Ministry to Vice-Premier. In spite of Kim Il-sung's "independent line," increased dependence on the USSR for military and economic aid had propelled the North Korean position progressively toward the Soviet orbit.[44]

- 1968-January-23: DPRK captured the USS Pueblo. With this event, DPRK can demonstrated independent initiative from the big communist powers, and its readiness to combat American imperialism. The USSR demonstrates more praise while China's response is less enthusiastic.[44][45]

- The Pueblo was seized on the eve of a preparatory meeting for a World Communist party conference, and the DPRK leaders hoped the incident would become a major focus of the conferences' attention. North Korea could further claim to have done more to harass the U.S. and help Communist brethren in Vietnam by direct and dangerous action than any other Communist nation apart from North Vietnamese itself.[44]

- By doing so the DPRK could demonstrate to China that North Korea was not a pawn of the Soviet Union and that it was as ready to combat American imperialism as was China herself. North Korea had succeeded in embarrassing the U.S. and in testing the reliability of its own allies.[44]

- The event was praised immediately by the Soviet Union and North Vietnam.[45]

- The first report in China's media came with a three-day delay,[45] on January 28. The statement gave firm support to the North Koreans but made no definite commitment. It also stated that "Should U.S. imperialism dare to embark on a new war adventure, it is bound to taste the bitter fruit of its own making and receive even more severe punishment".[45][af][45]

- The Pueblo was seized on the eve of a preparatory meeting for a World Communist party conference, and the DPRK leaders hoped the incident would become a major focus of the conferences' attention. North Korea could further claim to have done more to harass the U.S. and help Communist brethren in Vietnam by direct and dangerous action than any other Communist nation apart from North Vietnamese itself.[44]

- 1968-September: The DPRK celebrated its 20th anniversary. The cool relations with China was demonstrated with no presence a Chinese delegation, while on the other hand Kim made a speech in support of the USSR.[46]

- After the DPRK had failed to publicly support the USSR's invasion Czechoslovakia, both the North Korean press as well as Kim in a speech (of September 7) criticized Czechoslovak "errors", which appeared to be a sufficient concession to ensure continued Soviet support.[46]

- 1968-December-5: The DPRK and USSR sign an annual trade protocol.[46]

- 1968-1969: DPRK-PRC frontier disputes and incidents are reported in the Manchurian border.[15] China seemed to demand territorial "compensation" for the intervention of its "volunteers" in the Korean war.[27][15]

- In the summer of 1969, a Chinese road-building program was under way in the Changbai Mountains of Manchuria near strategic Mount Paektu, generally regarded as marking the Sino-Korean border but then mentioned in Chinese publications as being within China's Manchuria. [15][33]

- 1969: In 1969 the DPRK relations with the USSR appeared to continue to be good. DPRK-PRC relations might have begun to thaw.[47]

- 1969-April: The 9th National Congress of the Communist Party of China opened in Beijing on April 1st. No greetings were sent by DPRK.[48]

- Greetings were received from a number of foreign countries, though the majority of well-wishers were small parties and groups; there was no word from North Korea, and of the Eastern European bloc, only Romania sent greetings. Unlike earlier congresses, there were no foreign guests.[48]

- 1969-May:The most important visitor to North Korea during the year was N. V. Podgorny, Chairman of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet, in May.[49]

- Bringing with him several companions, including V. V. Kuznetsov, First Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, as well as the Vice Chairman of the State Committee on Economic Relations and the Chairman of the Maritime Territory Committee, it could be assumed that the Soviet visitors were interested in discussing the shooting down of the American EC-121 the previous month, and the possibilities of North Korea's attendance at the June "summit" meeting of communist parties in Moscow.[49]

- While condemning American "provocations" (not intrusions) in his public speech upon arrival in Pyongyang, Podgorny emphasized that "We resolutely advocate reduction of tension in the Far East and peace and security in that area."[ag] North Korea did not attend the summit meeting.[49]

- 1969-October-1: Chairman Choe Yong-gon led a strong North Korea delegation to attend in Beijing China's National Day. This was seen as an early indication that DPRK-PRC relations might had begun to improve.[47]

References and footnotes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Some reasons for the DPRK finally aligning itself with the PRC are that North Korea falls within the geographic orbit of China, that North Korea shared a common timing of revolution with their Chinese counterparts (and hence a common world outlook: Communism must be advanced by taking risks, and by revolution, with the United States the main target; like the Chinese, the North Koreans regard the CPSU and Khrushchev as guilty of "big power chauvinism," a tendency to accommodate the Soviet Union to the United States in disregard for Asian Communist interests, a callous attitude toward assistance for fraternal allies, and a minimization of the importance of the National Liberation Movements. (Scalapino, Robert A. (January 1963). "Korea: The Politics of Change". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1962: Part I. University of California Press. 3 (1): 31–40.)

- ^ The editorial "The True Character of the Traitor of Marxism-Leninism" of May 27 by Rodong Sinmun argued that the policy of "positive peaceful coexistence" was totally un-Marxian. By attributing the cause of the international tension to the existence of two military blocs, the editorial argued, the revisionists denied the cardinal principle that imperialism and its policies are the source of war and aggression. The policy of coexistence was also held to deny the class struggle in that it necessarily advocates class harmony in the domestic and international spheres

- ^ President Choi, who joined the Chinese Communist Party in 1926, made something of a Freudian slip when he was rounding off his speech to a rally in Peking on June 8, 1963. Speaking in Korean, the President said that the Korean people "under the leadership of your party" (the interpreter hesitated, but translated what had been said) would go forward with the Chinese people "sharing life, death and adversity." Peking radio in its Russian service later accommodatingly reported Choe as saying "the" Party, and substituted "joy" for "death."("Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly. Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies (15): 183–199. July–September 1963.)("Part III. The Far East". Summary of World Broadcasts. British Broadcasting Corporation (1270): A3/4.)

- ^ "[Choi and Liu] held cordial and friendly talks on the question of further consolidating and developing the relations of friendship, unity and mutual assistance and cooperation between the two Parties and the two countries and on important questions concerning the current international situation and the international communist movement. The results of the talks showed that both sides were completely identical in their stand and views." ("Joint Statement of President Choi Yong Kun and Chairman Liu Shao- ch'i. (Supplement to Korea Today, No. 8)". Korea Today. North Korea (DPRK): Foreign Languages Publishing House. 1963.)(Lee, Chong-Sik (January 1964). "Korea: In Search of Stability". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1963: Part I. University of California Press. 4 (1): 656–665.)

- ^ These statements gave the appearance of North Korea choosing to side with PRC against the USSR, however Kim still made efforts to retain a semblance of equidistance when he told a Japanese delegation on September that he did not want to see differences develop.[19]

- ^ This was published in the 1963 edition of Mezhdunarodny Yezhegodnik: Politika i Ekonomika (International Yearbook of Politics and Economics) published by the Institute of World Economy and International Relations in Moscow. It was passed for publication between September 12-24, 1963. Twelve countries were said to be socialist. Yugoslavia, Cuba and North Vietnam were in; China, Albania and North Korea were out. ("Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly. Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies (17): 261–271. January–March 1964. Retrieved 27 February 2014.)

- ^ Representatives of twenty-eight nations and regimes, including Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, attended the seminar. Among the topics considered were "Self-Reliant Recovery and Construction of Independent National Economy" and "Neo-Colonialism and the Asian Economy." (Lee, Chong-Sik (January 1965). "Korea: Troubles in a Divided State". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1964: Part I. University of California Press. 5 (1): 25–32.)

- ^ A Pravda editorial of 1964 charged that the seminar was "guided by interests far removed from the economic problems of the Asian countries" and that it sought to "split the Asian and African movements" and "vilified the socialist countries." In rebuttal editorial of September 7, 1964, Rodong Sinmun proclaimed: "What a striking coincidence of the Voice of Pravda with the Voice of America! (...) What a slighting attitude of contempt and arrogance this is! What overbearing, insolent, and shameless nonsense it is! These are the words that can be used only by the great power chauvinists who are in the habit of thinking that they are entitled to decide and order everything (...)". Reviewing aid received from the Soviet Union, the editorial said: "In rendering aid in the rehabilitation and construction of [certain] factories (...) you furnished us with equipment, stainless-steel plates, and other materials at prices much higher than the world-market prices and took away from us scores of tons of gold and quantities of valuable non-ferrous metals and raw materials at prices much lower than the world- market prices. Would it not be a reasonable attitude, when you talk about your aid to us, to mention also that you took valuable materials produced by our people through arduous labor in the most difficult days of our life?" (Lee, Chong-Sik (January 1965). "Korea: Troubles in a Divided State". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1964: Part I. University of California Press. 5 (1): 25–32.)

- ^ The Rodong Sinmun carried another biting editorial on April 19, 1964, entitled "Let Us Prevent the Scheme to Split the International Communist Movement." This attacked the Soviet Union's "slander and defamation" of the fraternal parties. The editorial charged that the Soviet Union started the open polemics and that the other parties were entitled to reply. North Korea, according to the editorial, had demanded immediate cessation of the open polemics when it all started and had opposed the divisive attempt to isolate the fraternal parties and exclude them from the international camp: "Up to the present, we have striven to solve internally even the unbearable problems for the sake of the unity of the socialist camp." (Lee, Chong-Sik (January 1965). "Korea: Troubles in a Divided State". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1964: Part I. University of California Press. 5 (1): 25–32.)

- ^ Some critics in Seoul, however, argued that the editorial ought to be interpreted more as a subterfuge designed to appeal to South Korean desires for unification and to disguise the subservience of the North to the Soviet Union. In any case, the more pronounced movement of North Korea away from Communist China on ideological matters was consistent with a theory of leadership that had been expounded by Kim Il-Sung who had argued that running a government is like driving an automobile: if one veers too far right or left, the thing to do is to steer back toward the middle of the road. (Paige, Glenn D. (January 1967). "1966: Korea Creates the Future". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1966: Part I. University of California Press. 7 (1): 21–30.)

Academic journals and sources

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Suhrke, Astri (July 1973). "Gratuity or Tyranny: The Korean Alliances". World Politics. 25 (4). Cambridge University Press: 508–532. doi:10.2307/2009950. JSTOR 2009950. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Macadam, Ivison; Cleeve, Margaret, eds. (1961). The Annual Register 1960. 202. Great Britain: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd. p. 174-175, 367, 376, 555, 564. ISBN 9781615403721. OCLC 900044307.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (15). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 183–199. July–September 1963. JSTOR 3082096. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (2). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 73–100. April–June 1960. JSTOR 651443. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (3). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 114–127. July–September 1960. JSTOR 763297. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b c "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (4). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 127–140. October–December 1960. JSTOR 763314. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Koh, B. C. (January 1974). "North Korea: Old Goals and New Realities". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1973: Part I. 14 (1). University of California Press: 36–42. doi:10.2307/2642836. JSTOR 2642836. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Haggard, M. T. (August 1965). "North Korea's International Position". Asian Survey. 5 (8). University of California Press: 375–388. doi:10.2307/2642410. JSTOR 2642410. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b c "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (7). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 161–175. July–September 1961. JSTOR 763331. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Macadam, Ivison; Cleeve, Margaret, eds. (1962). The Annual Register 1961. 203. Great Britain: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd. p. 365, 356. OCLC 904303347.

- ^ a b Koh, B. C. (January 1977). "North Korea 1976: Under Stress". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1976: Part I. 17 (1). University of California Press: 61–70. doi:10.2307/2643441. JSTOR 2643441. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Hook, Brian; Wilson, Dick; Yahuda, Michael (December 1978). "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (76). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 930–986. JSTOR 652657. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Scalapino, Robert A. (January 1963). "Korea: The Politics of Change". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1962: Part I. 3 (1). University of California Press: 31–40. doi:10.2307/3024648. JSTOR 3024648.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lee, Chong-Sik (January 1964). "Korea: In Search of Stability". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1963: Part I. 4 (1). University of California Press: 656–665. doi:10.2307/3023541. JSTOR 3023541.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Zagoria, Donald S.; Kim, Young Kun (December 1975). "North Korea and the Major Powers". Asian Survey. 15 (12). University of California Press: 1017–1035. doi:10.2307/2643582. JSTOR 2643582. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Macadam, Ivison; Grindrod, Muriel, eds. (1963). The Annual Register 1962. 204. Great Britain: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd. p. 369. ISSN 0066-4057. OCLC 929722444.

- ^ Paige, Glenn D.; Lee, Dong Jun (April–June 1963). "The Post-War Politics of Communist Korea". The China Quarterly. 14 (14). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 17–29. doi:10.1017/S0305741000020993. JSTOR 651340. S2CID 154816371. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Ma-k'o-szu-lieh-ning-chu-icheng-tang tsai wo-kuo ti ch'uang-chien chi-ch'i chuang- ta ho fa-chan" ("The Creation, Strengthening, and Development of a Marxist-Leninist Party in our Country"), Hsin Ch'ao-hsien (新朝鲜 - New Korea), No. 4 (162), (1962), pp. 7-12.

- ^ a b c Macadam, Ivison; Grindrod, Muriel, eds. (1964). The Annual Register 1963. 205. Great Britain: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd. p. 378-379. ISSN 0066-4057. OCLC 929722444.

- ^ a b c "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (16). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 169–180. October–December 1963. JSTOR 651584. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (17). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 261–271. January–March 1964. JSTOR 3451156. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ F.C. Jones (Korea chapter) (1965). Macadam, Ivison; Grindrod, Muriel (eds.). The Annual Register 1964. 206. Great Britain: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd. p. 364, 355.

- ^ a b Park, Choon-ho; Cohen, Jerome Alan (Autumn 1975). "The Politics of China's Oil Weapon". Foreign Policy (20). Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive, LLC: 28–49. doi:10.2307/1148125. JSTOR 1148125. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (19). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 181–201. July–September 1964. JSTOR 651513. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (20). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 171–187. October–December 1964. JSTOR 651717. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d Lee, Chong-Sik (January 1965). "Korea: Troubles in a Divided State". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1964: Part I. 5 (1). University of California Press: 25–32. doi:10.2307/2642178. JSTOR 2642178.

- ^ a b Clemens, Walter C. Jr (June 1973). "Grit at Panmunjom: Conflict and Cooperation in a Divided Korea". Asian Survey. 13 (6). University of California Press: 531–559. doi:10.2307/2642962. JSTOR 2642962. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (25). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 243–251. January–March 1966. JSTOR 3082115. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Kim, C. I. Eugene (January 1966). "Korea in the Year of Ulsa". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1965: Part I. 6 (1). University of California Press: 34–42. doi:10.2307/2642258. JSTOR 2642258.

- ^ Macadam, Ivison; Grindrod, Muriel, eds. (1966). The Annual Register 1965. 207. Great Britain: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd. p. 141, 536.

- ^ Haggard, M. T. (August 1965). "North Korea's International Position". Asian Survey. V (8): 378.

- ^ "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (21). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 202–220. January–March 1965. JSTOR 651336. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b Rees, David (February–March 1970). "The New Pressures from North Korea". Conflict Studies.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Drachkovitch, Milorad M.; Gann, Lewis H., eds. (1967). Yearbook on International Communist Affairs 1966. The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace; Stanford University. p. 347-348, 454, 523. LCCN 67-31024. OCLC 929695790.

- ^ a b Report from the Central Committee, CPSU to the 23rd Congress of the CPSU. By L.I. Brezhnev, First Secretary of the CC, CPSU. Section 1: The Socialist World System and the Struggle of the CPSU to Strengthen Its Unity and Might. Published in Pravda on March 30, 1966 as well as from Information Bulletin issued by the World Marxist Review Publishers, Nos. 70-71, May 12, pp. 7-32

- ^ a b "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (28). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 146–194. October–December 1966. JSTOR 651400. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e F.C. Jones (Chapter on Korea) (1967). Macadam, Ivison; Usborne, Margaret; Boas, Ann (eds.). The Annual Register 1966. 208. Great Britain: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd. p. 381.

- ^ a b Paige, Glenn D. (January 1967). "1966: Korea Creates the Future". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1966: Part I. 7 (1). University of California Press: 21–30. doi:10.2307/2642450. JSTOR 2642450.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cho, Soon Sung (January 1968). "Korea: Election Year". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1967: Part I. 8 (1). University of California Press: 29–42. doi:10.2307/2642511. JSTOR 2642511.

- ^ a b "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (32). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 184–227. October–December 1967. JSTOR 651433. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ F.C. Jones (Chapter on Korea) (1968). Macadam, Ivison; Usborne, Margaret; Boas, Ann (eds.). The Annual Register 1967. 209. Great Britain: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd. p. 375.

- ^ a b c d e "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (30). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 195–249. April–June 1967. JSTOR 651878. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (42). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 166–186. April–June 1970. JSTOR 652051. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Cho, Soon Sung (January 1969). "North and South Korea: Stepped-Up Aggression and the Search for New Security". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1968: Part I. 9 (1). University of California Press: 29–39. doi:10.2307/2642092. JSTOR 2642092. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (34). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 158–194. April–June 1968. JSTOR 651382. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Macadam, Ivison; Usborne, Margaret; Boas, Ann, eds. (1969). The Annual Register 1968. 210. Great Britain: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd. p. 365. ISBN 582 11968 5.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ a b Macadam, Ivison; Usborne, Margaret; Boas, Ann, eds. (1970). The Annual Register 1969. 211. Great Britain: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd. p. 366. ISBN 582 11969 3.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ a b "Quarterly Chronicle and Documentation". The China Quarterly (39). Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies: 144–168. July–September 1969. JSTOR 652554. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Kim, Joungwon Alexander (January 1970). "Divided Korea 1969: Consolidating for Transition". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1969: Part I. 10 (1). University of California Press: 30–42. doi:10.2307/2642143. JSTOR 2642143.

News and other sources

[edit]- ^ Korea Week. 6 (18). Washington, D.C.: 3 September 30, 1973.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Rodong Sinmun. North Korea: Workers' Party of Korea. December 16, 1962.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Editorial". Rodong Sinmun. North Korea: Workers' Party of Korea. January 30, 1963.

- ^ "Editorial: The True Character of the Traitor of Marxism-Leninism". Rodong Sinmun. North Korea: Workers' Party of Korea. May 27, 1963.

- ^ "Editorial". Rodong Sinmun. North Korea: Workers' Party of Korea. August 22, 1963.

- ^ a b "Joint Statement of President Choi Yong Kun and Chairman Liu Shao- ch'i. (Supplement to Korea Today, No. 8)". Korea Today. North Korea (DPRK): Foreign Languages Publishing House. 1963.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ For the Japanese text of the "Pyongyang Declaration of the Asian Economic Seminar," see Chosen Shiryo, July 1964, 22-24. The text of the North Korean delegation's report is printed in ibid., pp. 7-21. The first seminar was held in Colombo in 1962.

- ^ "Editorial:Let Us Prevent the Scheme to Split the International Communist Movement". Nodong Sinmun. North Korea: Workers' Party of Korea. April 19, 1964.

- ^ "Editorial". Nodong Sinmun. North Korea: Workers' Party of Korea. February 15, 1965.

- ^ "Peking Review" (PDF). Peking Review (Beijing Review 北京周報). 8 (48). China International Publishing Group. Novermber 26, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-01-29. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Part III. The Far East". Summary of World Broadcasts (1985). British Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Part III. The Far East". Summary of World Broadcasts (2034). British Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Part III. The Far East". Summary of World Broadcasts (2039). British Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Information Bulletin, Nos. 74-77". World Marxist Review. July 20, 1966. p. 63.

- ^ "Editorial: Let Us Defend Independence". Rodong Sinmun. North Korea: Workers' Party of Korea. August 12, 1966.

- ^ "Part III. The Far East". Summary of World Broadcasts (2238). British Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "International service in French". Tirana: Albanian Telegraphic Agency (ATA). November 4, 1966.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dong-a Ilbo reported that Pak Kim-ch'ol, Yi Hyo-sun, Yim Ch'un-ch'u and Kim To-man were purged at the 15th plenary meeting of the Central Committee in May 1967. However, the reliability of this information was uncertain. See Dong-a Ilbo, October 2 and November 7, 1967.

- ^ See Arai Seidai, "Kita Chosen no Naisei to Gaiko" (Internal Politics and Diplomacy of North Korea)

- ^ Kokusai Mondai. No. 88. Japan: Japan Institute of International Affairs. July 1967. p. 18-25.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Dong-a Ilbo. South Korea. February 21, 1967.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Dong-a Ilbo. South Korea. February 23, 1967.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Dong-a Ilbo. South Korea. February 27, 1967.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Kim-Il-song, "Hantei and Hanbei Toso o Kyoka Siyo" (Let Us Strengthen the Anti-imperialistic and Anti-American Struggle), in Chosen Shiryo, No. 76 (September 1967), pp. 2-7. This article was originally published in Cuba on August 12, 1967.

- ^ a b "(various issues)". Rodong Sinmun. North Korea. 1967.

- ^ Choga Kazuya, "Kita Chosen no Jishu Tokuritsu Rosen" (North Korea's Independence Line)

- ^ Kokusai Mondai. No. 95. Japan: Japan Institute of International Affairs. February 1968. p. 48-53.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Asahi Shimbun. Japan. September 30, 1968.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Asahi Shimbun. Japan. October 6, 1968.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Editorial". Rodong Sinmun. North Korea: Workers' Party of Korea. August 23, 1968.

- ^ United Press International release, April 10, 1968, published in Dong-a Ilbo, April 11, 1968.

- ^ "Peking Review" (PDF). Peking Review (Beijing Review 北京周報). 11 (5). China International Publishing Group. February 2, 1968. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-01-29. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ Pravda. USSR (Russia): Central Committee of the CPSU. May 17, 1969.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Timeline: 1969-1979

[edit]1969: Improved relations with China and the regaining of equidistance of DPRK with PRC and USSR

[edit]- 1969: The end of the Cultural Revolution in China opened the door to improved relations between the PRC and DPRK.[1][2][3]

- 1969-1970: North Korea was reverting steadily to the fence-sitting posture in the Sino-Soviet dispute which had been habitual in the years before the Cultural Revolution.[4] Exchanges of visits and courtesies between China and North Korea were treated with great prominence in the Chinese press, as did the affairs of the North Korean Party Congress.[5]

- 1969-April: a U.S. reconnaissance plane was downed over North Korea. The Russians helped the Americans to search for survivors, while China denounced the 'aggression.'[6]

- 1969-October-1: For the first time since 1965 North Korea sent a special delegation, led by President Choe, to China's National Day celebration. The delegation won concessions from China.[6][1]

- The delegation reportedly also won Chinese concessions on the disputed Mount Paektu territory as well as a new trade arrangement calling for annual transactions totaling $120 million.[1]

- This event was considered the turning point in China-DPRK relations.[1] The DPRK delegation flew to Beijing at the last minute,[7] and it also included Foreign Minister Pak Song-chol.[2]

- 1969-October-8: The DPRK sent a message of congratulations on the success of China's two nuclear tests in late September.[a] No such message had been sent after the test in December 1968.[2]

- 1970: China criticized the USSR, and the USSR said Mao was responsible for the death of his son Mao Anying during the Korean War.[8][b][I]

- 1970-January-30: New China News Agency announced that China and North Korea had held "friendly consultations" to conclude the Yalu and Tumen Rivers Navigation Coordination Committee Agreement.[6]

- This was the warmest description of border relations between the two countries since 1965.[6]

- 1970-February-17: Hyon Chun-Kuk, the North Korean Ambassador, who returned home in September 1967 during the Cultural Revolution, returned to Beijing and was received by Zhou Enlai on 17 February,[4] with whom he had a "cordial and friendly talk". The NCNA reported the event.[6]

- 1970-February: In late February, a Chinese trade delegation led by the Vice-Minister of Foreign Trade, Chou Hua-min, visited Pyongyang.[4]

- It was also noticeable that the North Korean and Chinese official news agencies began again to quote from each other.[4]

- 1970-March-4: In a gesture of renewed friendship, Son Gwan-oj was appointed North Korean ambassador to Albania, China's closest ally.[6]

- 1970-March-10: The Deputy-Chairman of the USSR State Commission for Foreign Economic Relations M.N. Suloyev, arrived in North Korea.[6]

- This visit was seen as a possible reminder to Pyongyang that the Soviet Union had more resources for offering aid than China.[6]

- 1970-March: Pyongyang refused to take part in a joint oceanographic research project with the Soviet Union on the grounds that Moscow, contrary to agreement, had invited some Japanese scientists to attend.[6]

- 1970-April-5: Premier Zhou Enlai paid a state visit to North Korea on April 5-7, the first top-level contact between the two countries since Choe Yong-gon visited China in 1964.[6] It was also Zhou Enlai's first diplomatic visit to any foreign country after the Cultural Revolution.[1][3]

- The common denominator of the revived Pyongyang-Beijing friendship was their mutual fear of a hostile U.S.-Japanese alliance designed to revive Japanese militarism (the automatic extension of the U.S.-Japanese Security Treaty in June reinforced this view).[9]

- This was Zhou's first journey outside China since 1966 and marked both the obvious attempts being made to improve relations with Korea and a return to normality in the Foreign Ministry. The joint communiqué following this visit condemned "modern revisionism" as well as "imperialism" and reactionaries of various countries" and this seemed to be a sign that Korea was moving closer to China in terms of the Sino-Soviet dispute than had been the case since 1967.[8]

- In their public statements, the Chinese emphasized that Korea had been the historical route to Manchuria, while the North Koreans vividly recalled who fought beside them in 1950-1953. As Kim Il-sung told Zhou: "Should U.S. imperialism and Japanese imperialism forget the historical lesson and dare to launch a new adventuresome war of aggression again, then the Korean people will again, as in the past, together with the Chinese people, fight against the enemy to the end."[c][6][10][1]

- This visit brought about new Chinese commitments for military and economic assistance for the following six years[3], in preparation for the North Korea's new six-year plan of 1971-76.[3] Such commitments were probably later increased during Kim Il-sung's visit to Beijing in the spring of 1975.[1]

- 1970-April-23: The appointment of a new Chinese Ambassador to North Korea was announced, as part of China's post-Cultural Revolution normalization of relations with multiple countries.[4][3] The previous Ambassador, Chiao Jo-yu, had returned to China in mid-1967, leaving the post empty for almost three years due to the strained relations. The new Ambassador,[4][3] Li Tun-chuan, had previously been posted in the Republic of Dahomey (present-day Benin) until January 1966 when Dahomey broke off diplomatic relations with China.[4]

- 1970-April-late: The Soviet Chief Chief of General Staff Zhukov. Just like with China, the DPRK also concluded a new six-year trade and aid agreement, in preparation for the North Korea's new six-year plan of 1971-76.[3]

- 1970: Beijing signed a five-year aid agreement with the DPRK and quietly dropped its claim to a 100-square mile strip of DPRK territory bordering Manchuria.[10]

- 1970-June-25: The 20th anniversary of the beginning of the Korean War was marked with large-scale celebrations of the "blood-cemented revolutionary friendship between the Chinese and Korean people."[6][8][3]

- A joint editorial from the People's Daily, Red Flag and Liberation Army Daily was published on June 25 and a rally held in Beijing on the same day. [8][d][e][f]

- Delegations were exchanged between the two countries, the Chinese one led by the Chief of Staff of the PLA, Huang Yung-sheng, and the North Korean by the Foreign Minister, Pak Song-chol. They were received respectively by Mao and Kim II-sung and a series of fraternal banquets was held in both capitals attended by senior government and military leaders. [8][3]

- Although the 15th anniversary of the Korean War was celebrated in 1965 and there had been annual commemoratory editorials until 1966, the scale of the celebrations that year, as well as their resumption after a gap of four years, was clearly intended to demonstrate that relations were on a new and improved footing.[8]

- 1970-July-25: A DPRK military delegation visited China.[11][3]

- A North Korean military delegation led by General Oh Jin Woo, the Korean Chief of the General Staff, and including the Commander of Artillery, Commander of the Navy and Deputy Commander of the Air Force, visited China from 25 July to 4 August at the invitation of Huang Yongsheng. They were received by Chairman Mao and had "very cordial and friendly" talks with both Zhou Enlai and Huang Yongsheng.[11]

- 1970-July-27: China and North Korea published a joint editorial on the 17th Anniversary of the Korean armistice.

- the People's Daily marked anniversary with a large character editorial published jointly with the People's Liberation Army Daily and entitled "U.S. imperialism has not laid down its butcher's knife." This said that, in face of United States "aggressive activities in Asia," the Chinese people would "further strengthen their unity" with the Korean people and those of the three Indo-China states. After quoting Kim II Sung as saying that the Korean people were "fully prepared to crush any surprise attack," the editorial continued: "If U.S. imperialism dares to reimpose war upon the Korean people, the Chinese people will, as always, stand side-by-side with the fraternal Korean people to defeat the U.S. aggressors completely."[11][g][h]

- This anniversary had not been noted by an editorial in the Chinese press for a number of years and was clearly being used as a peg for statements about friendship with North Korea.[11]

- Delegations were also exchanged in celebrating the anniversary.[3]

- 1970-August-15: The commemoration of the Russian liberation of North Korea was relatively low-key.[6]

- K. T. Mazurov, first Deputy Chairman of the U.S.S.R. Council of Ministers, called for an "Asian Collective Security" arrangement; the KCNA report of the speech omitted this passage.[6]

- 1970-October-17: Two new agreements were signed: one on economic and technical aid and the other on the exchange of goods from 1971 to 1976.[5][3]

- The last known economic and technical aid agreement had been signed in 1960 to cover the period 1961-64. Since 1967 there had been annual protocols on the exchange of goods.[5]