User:CasidyB/sandbox

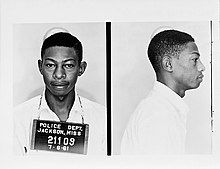

Miller G. Green was born May 19, 1943 in Bentonia, MS, and grew up in Jackson.[1] When Miller was 18 he worked at The Dollar Store as a Senior at Lanier High School and participated in The Civil Rights Movement.[2] He is now in the 1961 Freedom Riders Roll Call[3] as a veteran of the Civil Rights movement and mentioned in the long lists that both Breach of Peace[4] and The Freedom Riders[2] disclose with utmost respect.

The Movement

[edit]Arrested on July 7, 1961, at the Trailways bus station, Miller now gets to tell his story in interviews such as with MLive:

It was 1961 when Miller Green first walked through the "white entrance" at his hometown bus station in Jackson, Mississippi. A white onlooker called him names and warned him not to go through. "I heard another voice that said, 'Don't look back, or everyone behind you is going to leave you,' and I didn't look back, and I walked in." he said.[5]

Now in his mid-60s, Green spoke about the Freedom Rider movement Monday night at the Flint Public Library with author Eric Etheridge, who recently profiled Green and other riders in his 2008 book, "Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders."[1] Green and his fellow Freedom Riders were among hundreds of black and white activists -- mostly students -- who traveled to bus stations throughout the South to demonstrate that a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that outlawed segregation in bus stations was not being enforced. The first Freedom Riders left from Washington, D.C., and were supposed to travel to New Orleans but were sidetracked in the Alabama cities of Montgomery and Birmingham, where several of the them were assaulted by a mob, Etheridge said.[5]

"In Birmingham, they were beaten for 20 minutes before the cops showed up, the riders were absolutely stressed out, and many of them were injured."[5] He said. By the time the riders reached Jackson, local officials agreed to give them police protection, even though all of the riders would be arrested for their actions. After Green and others entered the bus station, the police were soon called. "I had never seen a machine gun before, It looked like all of the Jackson Police Department was out there."[5]

Green, who was arrested and thrown in the city jail, was among more than 350 riders arrested during the movement that summer.[1] As more and more riders were arrested, the Jackson jail became so overcrowded that Green and others had to be sent to a maximum security prison. At times, Green said, so many of them were in the cell block that they were just inches apart. "We took turns with some people standing up, while others laid down to sleep," [5]

The riders spent the most of the summer in jail. "There were times when you're out of your mind, you don't know if you are going to survive or not, but despite what we were going through, we still kept on doing what we were doing."[5] The riders had proven their point, and the Supreme Court ruling began to be enforced.

"When I look back, I'm very thankful I made that decision (to walk through that door at the bus station," Green said. Byron Valentine, 20, of Flint called Green's speech "beautiful."

"The fire that I see in him, that's the fire that's inside me right now," he said.[5]

Since then

Miller worked in the civil rights movement in Mississippi doing voter registration. Attended Utica Junior College, in nearby Utica, for a year then moved to Chicago in 1963. Worked in a printing plant and a prepared foods factory. He was active in the movement, working with Operation Breadbasket[6] and Operation PUSH[7] to improve economic opportunities in black communities.

In the mid-seventies and early eighties, he started and ran several businesses, including clothing stores and a hair salon. Later worked as a director of security for St. Bernard Hospital, and as a manager of a blood bank. Today he lives in the Englewood neighborhood in Chicago and runs Citizens for a Better West Englewood.

Oral History

[edit]On what happened in Mississippi in 1961:

"What happened in Mississippi was basically the whole state was put on a bunch of young people, 17, 18 years olds. The ministers ran. They went fishing. The Ph.Ds, they ran. So it came down to a bunch of teenagers who grew up in Mississippi and knew the situation, who knew what the consequences could be. Yet we carried that on our shoulders. The adults were nowhere to be found. They ran. The only somebody I know that was an adult at the time was Medgar Evers [the head of the NAACP in Mississippi].[8] Everybody else disappeared. Nobody was there. It was a very frustrating situation, to know that there were no adults who was willing to take that chance. We had seen what had been done to Emmett Till.[9] I remember when it happened. The fear escalated so that when it got dark and you was away from home and you saw car lights coming on, you ran, not knowing who would be in that car. We lived with that. And come ‘61, you asking young men to go and do something that they’d seen nobody ever do."[1]

Recruitment

[edit]Miller Green was in El Ranchos, a place the high school kids hung out at. Sitting in the booth, Miller and his friends were approached by a man in overalls, "Which was very unusual. You expected to see a person like that out in the country, at juke joint." This man sat down with them and introduced himself as James Bevel.[10] Bevel told Millers group about the Freedom Rides, and Miller described it as "a spirit coming over us, like the disciples of Christ, we left without telling anyone". They hitchhiked back to the office. When they got there, they met Tom Gaither, who was a young field secretary and lawyer, Reverend Bevel’s wife, Diane Nash,[11] who had just got out of jail that evening and were told what what the plan was,[1] they were told of the Freedom Rides.

"I said, well, if I don’t go tonight, I’m not going, and immediately Rev. Bevel and Diane Nash felt that they had a person in the group who was willing. So they proceeded to continue to talk about what they had been trying to do and what the situation was. And I’m looking at Diane Nash, and at the time Diane Nash was a beautiful girl, and I said to myself, this young lady here just got out of jail and she’s beautiful. I said to myself, if she can take a chance, then no reason why I can’t go."[1]

They were given $50–60 to take a bus to New Orleans and told someone would meet them at the station provided they could buy tickets. "After everyone agreed, they dropped us off in front of the Trailway Bus Station. Mind you, I had never seen an African American in there at all. I don’t ever remember seeing a black cab driver there. So now, you are in the process of going into a place that you grew up in seeing non-blacks in, and you know what the situation is, you know what the rule of law is in the state of Mississippi." Miller was in front of the group approaching the door. After being arrested, the police blamed Martin Luther King Jr.[12] for persuading Miller and his group into protesting and told them to call their parents to pick them up and go home.

"So I told the police I was dissatisfied with the way things were, and I said I will be here to the jails rot. We walked around our cells all night. No one was there watching us. They let us have our way. I guess the next morning, probably about 6:30, they recognized that we wasn’t going anywhere, and that’s when they started fingerprinting us."[1] Category:Activism

External Links (Bibliography)

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Etheridge., Eric (2009-02-22). "Miller Green". Breach of Peace. Retrieved 2018-02-04.

- ^ a b Arsenault, Raymond (2006-01-15). Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199755813.

- ^ "Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement -- Freedom Riders Roll Call". www.crmvet.org. Retrieved 2018-02-04.

- ^ "Breach of Peace (book)". Wikipedia. 2017-08-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Freedom Rider Miller Green tells his story from 1961". MLive.com. Retrieved 2018-02-04.

- ^ "Operation Breadbasket (1962-1972)". kingencyclopedia.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Operation PUSH (People United to Serve Humanity) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". www.blackpast.org. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Medgar Evers - Black History - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Emmett Till". Wikipedia. 2018-02-02.

- ^ "James Bevel". Biography. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Diane Nash". Wikipedia. 2018-02-04.

- ^ "Martin Luther King Jr". Wikipedia. 2018-02-02.