User:CPotter96/Golden Haggadah

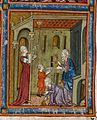

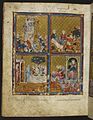

The Golden Haggadah is an illuminated Haggadah, a ritual text used in the celebration of Passover, created around the year 1320 in Catalonia.[1] There are 56 miniatures in the manuscript and it is one of the most lavishly decorated examples of a medieval Haggadah. It is now in the British Library.[2]

History

[edit]The Golden Haggadah is presumed to have been created sometime around c.1320-1330. While originating in Spain it is believed that the manuscript found its way to Italy in possession of Jews banished from the country in 1492.[3]

The original Illustrators for the manuscript are unknown. Based on artistic evidence the standing theory is there were at least two Illustrators. While there is no evidence of different workshops producing the manuscript there are two distinct artistic styles used respectively for one quire of eight folios on single sides of the leafs each. The first noticeable styling is of an artist who created somewhat standardized faces for their figures, but was graceful in their work and balanced with their color, The second style seen was very coarse and energetic in comparison.[3]

The original patron who commissioned the manuscript is unknown. However the prevailing theory on the first known owner was Rabbi Joav Gallico of Asti, who presented it as a gift to his daughter Rosa’s bridegroom Eliah Ravà on the occasion of their wedding 1602. This is known through the addition to the manuscript of a title page with inscription and page containing the Gallico family coat of arms in recognition of the ceremony.[3][4]

This current theory is based of the commemorative text inscribed in the title page which translated from its Hebrew text reads:

“NTNV as a gift [...] the honored Mistress Rosa,

(May she be blessed among the women of the tent), daughter of our illustrious

Honored Teacher Rabbi Yoav

Gallico, (may his Rock preserve him) to his son-in-law, the learned

Honored Teacher Elia (may his Rock preserve him)

Son of the safe,our Honored Teacher, the Rabbi R. Menahem Ravà (May he live Many good years)

On the day of his wedding and the day of the rejoicing of his heart,

Here at Carpi, the tenth of the month of Heshvan, Heh Shin Samekh Gimel (1602)”

The translation of this inscription can lead to debate on who the manuscript was originally given by, either the bride Rosa or her father Rabbi Joav. This originates with translation difficulties of the first word and a noticeable gap that follows it leaving out the word “to” or “by”. There are three theorized ways to read this translation.

The current theory is a translation of “He gave it [Netano] as a gift. . .[ignores references to Mistress Rosa]. . .to his son-in-law. . .Elia.” This translation works to ignore the reference to the bride and states that Rabbi Joav presented the manuscript to his new son in law. This presents the problem of why the bride would be mentioned after the use of the verb “he gave” and leaving out the follow up of “to” seen as prefix “le”. In support of this theory is that the prefix “le” is used in the second half of the inscription pointing to the groom Elia being the receiver thus the prevailing theory.

Another theory is a translation of “They gave it [Natnu] as a gift. . .Mistress Rosa (and her father?) to. . . his (her father’s) son-in-law Elia.” This supports the thought that the manuscript was given by both Rosa and Rabbi Joav together. The problem with this being the strange wording used to describe Rabbi Joav’s relationship to Elia and his grammatical placement after Rosa’s name as a form of afterthought.

The most grammatically correct theory is “It was given [Netano (or possibly Netanto)] as a gift [by]. . .Mistress Rosa to. . .(her father’s) son-in-law Elia.”. This presents that the manuscript was originally Rosa’s to whom she gifted it to her groom Elia. This theory also has its flaws in that this would mean the male version of “to give” was used for Rosa and not the feminne version. As well Elia is referred to as the son in law of her father, rather than merely her groom which makes little sense if Rabbi Joav was not involved in some form.[4]

Additional changes to the manuscript that can be dated include a mnemonic poem of the laws and customs of Passover on blank pages between miniatures included in the seventeenth century, Birth entry of a son in Italy 1689, and the signatures of Censors' for the years 1599, 1613, and 1629.[3]

Currently the Golden Haggadah can be found in the London British Library shelf mark MS 27210.[5][6] Having been collected by the British Museum in 1865 as part of the collection of Joseph Almanzi of Padua.[3]

Description

[edit]An Illustrated Manuscript Measuring by 24.7x19.5 cm. Made with Vellum and consisting of 101 leaves. It is a Hebrew text written in square Sephardi Script. There are fourteen full page miniatures each consisting of four scenes. It has a seventeenth century Italian binding of dark brown sheepskin. The manuscript has outer decorations of Blind-Tooled fan shaped motifs on the front and back.[3]

Content

[edit]Illuminations

[edit]Purpose

[edit]Gallery

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Golden Haggadah (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ^ "Golden Haggadah". The British Library. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ^ a b c d e f Narkiss, Bezalel (1969). Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts. California State University Library: Jerusalem, Encyclopaedia Judaica; New York Macmillan. p. 56. ISBN 0814805930.

- ^ a b Epstein, Marc (2011). The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination. New Haven : Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300158946.

- ^ Walther, Ingo (2001). Codices illustres: the world's most famous illuminated manuscripts 400-1600. California State University Library: Köln ; London ; New York : Taschen. p. 204. ISBN 3822858528.

- ^ "Collection Items-Golden Haggadah bl.uk". British Library.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Further Readings

[edit]- Bezalel Narkiss, The Golden Haggadah (London: British Library, 1997) [partial facsimile].

- Marc Michael Epstein, Dreams of Subversion in Medieval Jewish Art and Literature (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), pp. 16–17.

- Katrin Kogman-Appel, 'The Sephardic Picture Cycles and the Rabbinic Tradition: Continuity and Innovation in Jewish Iconography', Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 60 (1997), 451-82.

- Katrin Kogman-Appel, 'Coping with Christian Pictorial Sources: What Did Jewish Miniaturists Not Paint?' Speculum, 75 (2000), 816-58.

- Julie Harris, 'Polemical Images in the Golden Haggadah (British Library Add. MS 27210)', Medieval Encounters, 8 (2002), 105-22.

- Katrin Kogman-Appel, Jewish Book Art Between Islam and Christianity: the Decoration of Hebrew Bibles in Medieval Spain (Lieden: Brill, 2004), pp. 179–85.

- Sarit Shalev-Eyni, 'Jerusalem and the Temple in Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts: Jewish Thought and Christian Influence', in L'interculturalita dell'ebraismo a cura di Mauro Perani (Ravenna: Longo, 2004), pp. 173–91.

- Julie A. Harris, 'Good Jews, Bad Jews, and No Jews at All: Ritual Imagery and Social Standards in the Catalan Haggadot', in Church, State, Vellum, and Stone: Essays on Medieval Spain in Honor of John Williams, ed. by Therese Martin and Julie A. Harris, The Medieval and Early Modern Iberian World, 26 (Leiden: Brill, 2005), pp. 275–96 (p. 279, fig. 6).

- Katrin Kogman-Appel, Illuminated Haggadot from Medieval Spain. Biblical Imagery and the Passover Holiday (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006), pp. 47–88.

- Ilana Tahan, Hebrew Manuscripts: The Power of Script and Image (London, British Library, 2007), pp. 94–97.

- Sacred: Books of the Three Faiths: Judaism, Christianity, Islam (London: British Library, 2007), p. 172 [exhibition catalogue].

- Marc Michael Epstein, The Medieval Haggadah. Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2011), pp. 129–200.