User:Bcndoye/sandbox

| Lactate dehydrogenase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 1.1.1.27 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9001-60-9 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| lactate dehydrogenase A (subunit M) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | LDHA | ||||||

| Alt. symbols | LDHM | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 3939 | ||||||

| HGNC | 6535 | ||||||

| OMIM | 150000 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_005566 | ||||||

| UniProt | P00338 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| EC number | 1.1.1.27 | ||||||

| Locus | Chr. 11 p15.4 | ||||||

| |||||||

| lactate dehydrogenase B (subunit H) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | LDHB | ||||||

| Alt. symbols | LDHL | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 3945 | ||||||

| HGNC | 6541 | ||||||

| OMIM | 150100 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_002300 | ||||||

| UniProt | P07195 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| EC number | 1.1.1.27 | ||||||

| Locus | Chr. 12 p12.2-12.1 | ||||||

| |||||||

| lactate dehydrogenase C | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | LDHC | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 3948 | ||||||

| HGNC | 6544 | ||||||

| OMIM | 150150 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_002301 | ||||||

| UniProt | P07864 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| EC number | 1.1.1.27 | ||||||

| Locus | Chr. 11 p15.5-15.3 | ||||||

| |||||||

| D-lactate dehydrogenase, membrane binding | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

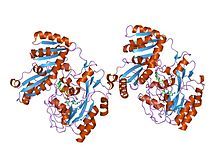

crystal structure of d-lactate dehydrogenase, a peripheral membrane respiratory enzyme. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Lact-deh-memb | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF09330 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0277 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR015409 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1f0x / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

A lactate dehydrogenase (LDH or LD) is an enzyme found in animals, plants, and prokaryotes.

Lactate dehydrogenase is of medical significance because it is found extensively in body tissues, such as blood cells and heart muscle. Because it is released during tissue damage, it is a marker of common injuries and disease.

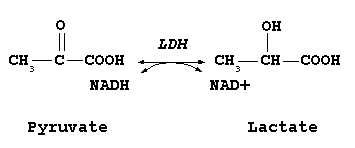

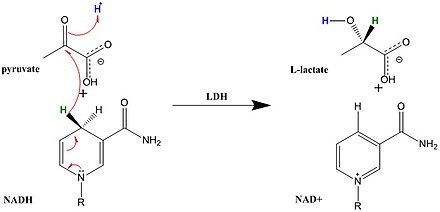

A dehydrogenase is an enzyme that transfers a hydride from one molecule to another. Lactate dehydrogenase catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate to lactate and back, as it converts NADH to NAD+ and back.

Lactate dehydrogenases exist in four distinct enzyme classes. Each one acts on either D-lactate (D-lactate dehydrogenase (cytochrome)) or L-lactate (L-lactate dehydrogenase (cytochrome)). Two are cytochrome c-dependent enzymes. Two are NAD(P)-dependent enzymes. This article is about the NAD(P)-dependent L-lactate dehydrogenase.

Reactions

[edit]

Lactate dehydrogenase catalyzes the interconversion of pyruvate and lactate with concomitant interconversion of NADH and NAD+. It converts pyruvate, the final product of glycolysis, to lactate when oxygen is absent or in short supply, and it performs the reverse reaction during the Cori cycle in the liver. At high concentrations of lactate, the enzyme exhibits feedback inhibition, and the rate of conversion of pyruvate to lactate is decreased.

It also catalyzes the dehydrogenation of 2-Hydroxybutyrate, but it is a much poorer substrate than lactate. There is little to no activity with beta-hydroxybutyrate.

Interactive pathway map

[edit]Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles.[§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "GlycolysisGluconeogenesis_WP534".

Enzyme regulation

[edit]This protein may use the morpheein model of allosteric regulation.[1]

Ethanol-induced hypoglycemia

[edit]Ethanol is dehydrogenated to acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase, and further into acetic acid by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. During this reaction 2 NADH are produced. If large amounts of ethanol are present, then large amounts of NADH are produced, leading to a depletion of NAD+. Thus, the conversion of pyruvate to lactate is increased due to the associated regeneration of NAD+. Therefore, anion-gap metabolic acidosis (lactic acidosis) may ensue in ethanol poisoning.

The increased NADH/NAD+ ratio also can cause hypoglycemia in an (otherwise) fasting individual who has been drinking and is dependent on gluconeogenesis to maintain blood glucose levels. Alanine and lactate are major gluconeogenic precursors that enter gluconeogenesis as pyruvate. The high NADH/NAD+ ratio shifts the lactate dehydrogenase equilibrium to lactate, so that less pyruvate can be formed and, therefore, gluconeogenesis is impaired.

Substrate Regulation

[edit]LDH is also regulated by the relative concentrations of its substrates. LDH becomes more active under periods of extreme muscular output due to an increase in substrates for the LDH reaction. When skeletal muscles are pushed to produce high levels of power, the demand for ATP in regards to aerobic ATP supply leads to an accumulation of free ADP, AMP, and Pi. The subsequent glycolytic flux, specifically production of NADPH and pyruvate, exceeds the capacity for pyruvate dehydrogenase and other shuttle enzymes to metabolize pyruvate. The flux through LDH increases in response to increased levels of pyruvate and NADPH to metabolize pyruvate into lactate.[2]

Transcriptional Regulation

[edit]LDH undergoes transcriptional regulation by PGC-1α. PGC-1α regulates LDH by decreasing LDH A mRNA transcription and the enzymatic activity of pyruvate to lactate conversion.[3]

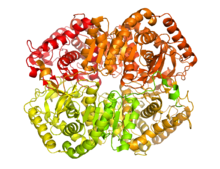

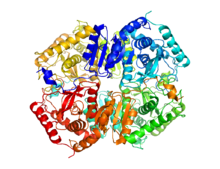

Enzyme isoforms

[edit]Functional lactate dehydrogenase are homo or hetero tetramers composed of M and H protein subunits encoded by the LDHA and LDHB genes, respectively:

- LDH-1 (4H)—in the heart and in RBC (red blood cells)

- LDH-2 (3H1M)—in the reticuloendothelial system

- LDH-3 (2H2M)—in the lungs

- LDH-4 (1H3M)—in the kidneys, placenta, and pancreas

- LDH-5 (4M)—in the liver and striated muscle[4]

The five isoenzymes that are usually described in the literature each contain four subunits. The major isoenzymes of skeletal muscle and liver, M4, has four muscle (M) subunits, while H4 is the main isoenzymes for heart muscle in most species, containing four heart (H) subunits. The other variants contain both types of subunits.

Usually LDH-2 is the predominant form in the serum. A LDH-1 level higher than the LDH-2 level (a "flipped pattern") suggests myocardial infarction (damage to heart tissues releases heart LDH, which is rich in LDH-1, into the bloodstream). The use of this phenomenon to diagnose infarction has been largely superseded by the use of Troponin I or T measurement.[citation needed]

Genetics in humans

[edit]The M and H subunits are encoded by two different genes:

- The M subunit is encoded by LDHA, located on chromosome 11p15.4 (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 150000)

- The H subunit is encoded by LDHB, located on chromosome 12p12.2-p12.1 (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 150100)

- A third isoform, LDHC or LDHX, is expressed only in the testis (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 150150); its gene is likely a duplicate of LDHA and is also located on the eleventh chromosome (11p15.5-p15.3)

Mutations of the M subunit have been linked to the rare disease exertional myoglobinuria (see OMIM article), and mutations of the H subunit have been described but do not appear to lead to disease.

Role in Muscular Fatigue

[edit]The onset of acidosis during periods of intense exercise is commonly been attributed to accumulation of lactic acid. From this reasoning, the idea of lactate production being a primary cause of muscle fatigue during exercise has been widely adopted. A closer, mechanistic analysis of lactate production under anaerobic conditions shows that there is no biochemical evidence for the production of lactate through LDH contributing to acidosis. While LDH activity is correlated to muscle fatigue[5], the production of lactate by means of the LDH complex works as a system to delay the onset of muscle fatigue.

LDH works to prevent muscular failure and fatigue in multiple ways. The lactate-forming reaction generates cytosolic NAD+, which feeds into the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase reaction to help maintain cytosolic redox potential and promote substrate flux through the second phase of glycolysis to promote ATP generation. This, in effect, provides more energy to contracting muscles under heavy workloads. The production and removal of lactate from the cell also ejects a proton consumed in the LDH reaction- the removal of excess protons produced in the wake of this fermentation reaction serves to act as a buffer system for muscle acidosis. Once proton accumulation exceeds the rate of uptake in lactate production and removal through the LDH symport[6], muscular acidosis occurs.

Medical Relevance

[edit]LDH is a protein that normally appears throughout the body in small amounts. Many cancers can raise LDH levels, so LDH may be used as a tumor marker, but at the same time, it is not useful in identifying a specific kind of cancer. Measuring LDH levels can be helpful in monitoring treatment for cancer. Noncancerous conditions that can raise LDH levels include heart failure, hypothyroidism, anemia, and lung or liver disease.[7]

Tissue breakdown releases LDH, and therefore LDH can be measured as a surrogate for tissue breakdown, e.g. hemolysis. Other disorders indicated by elevated LDH include cancer, meningitis, encephalitis, acute pancreatitis, and HIV. LDH is measured by the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) test (also known as the LDH test or Lactic acid dehydrogenase test). Comparison of the measured LDH values with the normal range help guide diagnosis.[8]

Cancer cells

[edit]LDH is involved in tumor initiation and metabolism. Cancer cells rely on anaerobic respiration for the conversion of glucose to lactate even under oxygen-deficient conditions (a process known as the Warburg effect[9]). This state of fermentative glycolysis is catalyzed by the A form of LDH. This mechanism allows tumorous cells to convert the majority of their glucose stores into lactate regardless of oxygen availability, shifting use of glucose metabolites from simple energy production to the promotion of accelerated cell growth and replication. For this reason, LDH A and the possibility of inhibiting its activity has been identified as a promising target in cancer treatments focused on preventing carcinogenic cells from proliferating.

Chemical inhibition of LDH A has demonstrated marked changes in metabolic processes and overall survival carcinoma cells. Oxamate is a cytosolic inhibitor of LDH A that significantly decreases ATP production in tumorous cells as well as increasing production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS drive cancer cell proliferation by activating kinases that drive cell cycle progression growth factors at low concentrations[10], but can damage DNA through oxidative stress at higher concentrations. Secondary lipid oxidation products can also inactivate LDH and impact its ability to regenerate NADH[11], directly disrupting the enzymes ability to convert lactate to pyruvate.

While recent studies have shown that LDH activity is not necessarily an indicator of metastatic risk[12], LDH expression can act as a general marker in the prognosis of cancers. Expression of LDH5 and VEGF in tumors and the stroma has been found to be a strong prognostic factor for diffuse or mixed-type gastric cancers.[13]

Hemolysis

[edit]In medicine, LDH is often used as a marker of tissue breakdown as LDH is abundant in red blood cells and can function as a marker for hemolysis. A blood sample that has been handled incorrectly can show false-positively high levels of LDH due to erythrocyte damage.

It can also be used as a marker of myocardial infarction. Following a myocardial infarction, levels of LDH peak at 3–4 days and remain elevated for up to 10 days. In this way, elevated levels of LDH (where the level of LDH1 is higher than that of LDH2) can be useful for determining whether a patient has had a myocardial infarction if they come to doctors several days after an episode of chest pain.

Tissue turnover

[edit]Other uses are assessment of tissue breakdown in general; this is possible when there are no other indicators of hemolysis. It is used to follow-up cancer (especially lymphoma) patients, as cancer cells have a high rate of turnover with destroyed cells leading to an elevated LDH activity.

Exudates and transudates

[edit]Measuring LDH in fluid aspirated from a pleural effusion (or pericardial effusion) can help in the distinction between exudates (actively secreted fluid, e.g. due to inflammation) or transudates (passively secreted fluid, due to a high hydrostatic pressure or a low oncotic pressure). The usual criterion is that a ratio of fluid LDH versus upper limit of normal serum LDH of more than 0.6[14] or 2⁄3[15] indicates an exudate, while a ratio of less indicates a transudate. Different laboratories have different values for the upper limit of serum LDH, but examples include 200[16] and 300[16] IU/L.[17] In empyema, the LDH levels, in general, will exceed 1000 IU/L.

Meningitis and encephalitis

[edit]High levels of lactate dehydrogenase in cerebrospinal fluid are often associated with bacterial meningitis.[18] In the case of viral meningitis, high LDH, in general, indicates the presence of encephalitis and poor prognosis.

HIV

[edit]LDH is often measured in HIV patients as a non-specific marker for pneumonia due to Pneumocystis jiroveci (PCP). Elevated LDH in the setting of upper respiratory symptoms in an HIV patient suggests, but is not diagnostic for, PCP. However, in HIV-positive patients with respiratory symptoms, a very high LDH level (>600 IU/L) indicated histoplasmosis (9.33 more likely) in a study of 120 PCP and 30 histoplasmosis patients.[19]

Dysgerminoma

[edit]Elevated LDH is often the first clinical sign of a rare malignant cell tumor called a dysgerminoma. Not all dysgerminomas produce LDH, and this is often a non-specific finding.

Prokaryotes

[edit]A cap-membrane-binding domain is found in prokaryotic lactate dehydrogenase. This consists of a large seven-stranded antiparallel beta-sheet flanked on both sides by alpha-helices. It allows for membrane association.[20]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Selwood T, Jaffe EK (March 2012). "Dynamic dissociating homo-oligomers and the control of protein function". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 519 (2): 131–43. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.020. PMC 3298769. PMID 22182754.

- ^ Spriet LL, Howlett RA, Heigenhauser GJ (2000). "An enzymatic approach to lactate production in human skeletal muscle during exercise". Med Sci Sports Exerc. 32 (4): 756–63. doi:10.1097/00005768-200004000-00007. PMID 10776894.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Summermatter S, Santos G, Pérez-Schindler J, Handschin C (2013). "Skeletal muscle PGC-1α controls whole-body lactate homeostasis through estrogen-related receptor α-dependent activation of LDH B and repression of LDH A." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110 (21): 8738–43. doi:10.1073/pnas.1212976110. PMC 3666691. PMID 23650363.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Van Eerd, J. P. F. M.; Kreutzer, E. K. J. (1996). Klinische Chemie voor Analisten deel 2. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-90-313-2003-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tesch P, Sjödin B, Thorstensson A, Karlsson J (1978). "Muscle fatigue and its relation to lactate accumulation and LDH activity in man". Acta Physiol Scand. 103 (4): 413–20. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1978.tb06235.x. PMID 716962.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Juel C, Klarskov C, Nielsen JJ, Krustrup P, Mohr M, Bangsbo J (2004). "Effect of high-intensity intermittent training on lactate and H+ release from human skeletal muscle". Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 286 (2): E245-51. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00303.2003. PMID 14559724.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stanford Cancer Center. "Cancer Diagnosis - Understanding Cancer". Understanding Cancer. Stanford Medicine.

- ^ "Lactate dehydrogenase test: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ WARBURG O (1956). "On the origin of cancer cells". Science. 123 (3191): 309–14. doi:10.1126/science.123.3191.309. PMID 13298683.

- ^ Irani K, Xia Y, Zweier JL, Sollott SJ, Der CJ, Fearon ER; et al. (1997). "Mitogenic signaling mediated by oxidants in Ras-transformed fibroblasts". Science. 275 (5306): 1649–52. doi:10.1126/science.275.5306.1649. PMID 9054359. S2CID 19733670.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ramanathan R, Mancini RA, Suman SP, Beach CM (2014). "Covalent Binding of 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal to Lactate Dehydrogenase Decreases NADH Formation and Metmyoglobin Reducing Activity". J Agric Food Chem. 62 (9): 2112–2117. doi:10.1021/jf404900y. PMID 24552270.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Xu HN, Kadlececk S, Profka H, Glickson JD, Rizi R, Li LZ (2014). "Is Higher Lactate an Indicator of Tumor Metastatic Risk? A Pilot MRS Study Using Hyperpolarized (13)C-Pyruvate". Acad Radiol. 21 (2): 223–31. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2013.11.014. PMC 4169113. PMID 24439336.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kim HS, Lee HE, Yang HK, Kim WH (2014). "High lactate dehydrogenase 5 expression correlates with high tumoral and stromal vascular endothelial growth factor expression in gastric cancer". Pathobiology. 81 (2): 78–85. doi:10.1159/000357017. PMID 24401755. S2CID 1735889.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heffner JE, Brown LK, Barbieri CA (April 1997). "Diagnostic value of tests that discriminate between exudative and transudative pleural effusions. Primary Study Investigators". Chest. 111 (4): 970–80. doi:10.1378/chest.111.4.970. PMID 9106577.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Light RW, Macgregor MI, Luchsinger PC, Ball WC (October 1972). "Pleural effusions: the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates". Ann. Intern. Med. 77 (4): 507–13. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-77-4-507. PMID 4642731.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Joseph J, Badrinath P, Basran GS, Sahn SA (November 2001). "Is the pleural fluid transudate or exudate? A revisit of the diagnostic criteria". Thorax. 56 (11): 867–70. doi:10.1136/thorax.56.11.867. PMC 1745948. PMID 11641512.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Joseph J, Badrinath P, Basran GS, Sahn SA (March 2002). "Is albumin gradient or fluid to serum albumin ratio better than the pleural fluid lactate dehydroginase in the diagnostic of separation of pleural effusion?". BMC Pulm Med. 2: 1. doi:10.1186/1471-2466-2-1. PMC 101409. PMID 11914151.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stein JH (1998). Internal Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1408–. ISBN 978-0-8151-8698-4. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ^ Butt AA, Michaels S, Greer D, Clark R, Kissinger P, Martin DH (July 2002). "Serum LDH level as a clue to the diagnosis of histoplasmosis". AIDS Read. 12 (7): 317–21. PMID 12161854.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dym O, Pratt EA, Ho C, Eisenberg D (August 2000). "The crystal structure of D-lactate dehydrogenase, a peripheral membrane respiratory enzyme". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (17): 9413–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.17.9413. PMC 16878. PMID 10944213.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

[edit]- Johnson WT, Canfield WK (1985). "Intestinal absorption and excretion of zinc in streptozotocin-diabetic rats as affected by dietary zinc and protein". J Nutr. 115 (9): 1217–27. doi:10.1093/jn/115.9.1217. PMID 3897486.

- Ein SH, Mancer K, Adeyemi SD (1985). "Malignant sacrococcygeal teratoma--endodermal sinus, yolk sac tumor--in infants and children: a 32-year review". J Pediatr Surg. 20 (5): 473–7. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(85)80468-1. PMID 3903096.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Azuma M, Shi M, Danenberg KD, Gardner H, Barrett C, Jacques CJ; et al. (2007). "Serum lactate dehydrogenase levels and glycolysis significantly correlate with tumor VEGFA and VEGFR expression in metastatic CRC patients". Pharmacogenomics. 8 (12): 1705–13. doi:10.2217/14622416.8.12.1705. PMID 18086000.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Masepohl B, Klipp W, Pühler A (1988). "Genetic characterization and sequence analysis of the duplicated nifA/nifB gene region of Rhodobacter capsulatus". Mol Gen Genet. 212 (1): 27–37. doi:10.1007/BF00322441. PMID 2836706. S2CID 21009965.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Galardo MN, Regueira M, Riera MF, Pellizzari EH, Cigorraga SB, Meroni SB (2014). "Lactate Regulates Rat Male Germ Cell Function through Reactive Oxygen Species". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e88024. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088024. PMC 3909278. PMID 24498241.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tesch P, Sjödin B, Thorstensson A, Karlsson J (1978). "Muscle fatigue and its relation to lactate accumulation and LDH activity in man". Acta Physiol Scand. 103 (4): 413–20. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1978.tb06235.x. PMID 716962.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Beck O, Jernström B, Martinez M, Repke DB (1988). "In vitro study of the aromatic hydroxylation of 1-methyltetrahydro-beta-carboline (methtryptoline) in rat". Chem Biol Interact. 65 (1): 97–106. doi:10.1016/0009-2797(88)90034-8. PMID 3345575.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Summermatter S, Santos G, Pérez-Schindler J, Handschin C (2013). "Skeletal muscle PGC-1α controls whole-body lactate homeostasis through estrogen-related receptor α-dependent activation of LDH B and repression of LDH A." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110 (21): 8738–43. doi:10.1073/pnas.1212976110. PMC 3666691. PMID 23650363.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Robergs RA, Ghiasvand F, Parker D (2004). "Biochemistry of exercise-induced metabolic acidosis". Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 287 (3): R502-16. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00114.2004. PMID 15308499. S2CID 2745168.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kresge N, Simoni RD, Hill RL (2005). "Otto Fritz Meyerhof and the elucidation of the glycolytic pathway". J Biol Chem. 280 (4): e3. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(20)76366-0. PMID 15665335.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Category:Chemical pathology Category:Tumor markers Category:EC 1.1.1 Category:Enzymes of known structure