Urbain de Saint-Gelais

His Excellency Urbain de Saint-Gelais | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Comminges | |

Cathedral of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges | |

| Church | Roman Catholic Church |

| Diocese | Comminges |

| Appointed | 1570 |

| Term ended | 5 February 1613 |

| Predecessor | Pierre d'Albret |

| Successor | Gilles de Souvré (évêque) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1540 |

| Died | 5 February 1613 |

| Parents | Louis de Saint-Gelais, seigneur de Lanssac Louise de La Béraudière |

Urbain de Saint-Gelais, bishop of Comminges (1540–5 February 1613) was a prelate, diplomat, military leader and rebel during the French Wars of Religion. Urbain was born in 1540, the illegitimate son of the royal favourite Louis de Saint-Gelais, seigneur de Lanssac and Louise de La Béraudière. Thanks to the court influence of his father, he secured the sensitive bishopric of Comminges on the border with Spain in 1570. He would hold this charge for the rest of his life. He quickly ingratiated himself with his flock, seeing to it that their privileges were affirmed by the king Henri III in 1574. His involvement in the first Catholic Ligue (League) in 1576 is speculated, though he remained in good royal graces, and was tasked in 1579 with conducting a diplomatic mission to Lisbon to champion the rights of the queen mother Catherine to the Portuguese throne, though the mission was not a success.

His involvement in the second Catholic Ligue that emerged in response to the death of the king's brother the duc d'Anjou (duke of Anjou) in 1584 which established the Protestant king of Navarre as the heir to the throne, is more definitive. He helped arrange the accord between the leaders of the Catholic ligue and the Spanish crown, and participated in the war with the crown in 1585, both by encouraging the estranged queen of Navarre in her rebellion and in his own military actions in Comminges. His see of Saint-Bertrand was sacked by a Protestant force in 1586 and he had to reconquer it by siege. He participated in the Estates General of 1588 as a ligueur aligned representative and fled from Blois after the king executed the leader of the Catholic ligue in a royal coup in December.

Arriving in Toulouse he marshalled the city towards the ligueur camp, being elevated to governor of the city for the ligue at the end of January for the war against the crown. In February two leading parlementaires in the city were accused of involvement in a royalist plot and lynched. The bishop of Comminges' involvement in this is a matter of debate. He established a new religious confraternity in the city and worked to build connections with the Spanish and raise a ligueur army for Toulouse. He found himself in conflict with the ligueur governor of Languedoc the vicomte de Joyeuse, who (alongside the duc de Mayenne) was unnerved by Comminges' Spanish sympathies. Joyeuse moved to oust him from Toulouse, and succeeded in November in forcing him from the city. The bishop returned to Comminges where he spent the next several years nourishing the local ligueur movement (known as the Ligue Campanère). He consistently supported the Spanish king Felipe II, working towards an invasion of France across the Pyrénées, something he advocated for both in his writings to the Spanish court, and when he visited Madrid on a diplomatic mission. As the war dragged on, the situation became increasingly bleak for the ligueur cause, with the king of Navarre (now styled Henri IV after the assassination of Henri III) converting to Catholicism and winning many converts to his cause. The bishop of Comminges remained defiant, despite a faux submission made in June 1594. It would only be with the absolution of Henri IV by the Pope in September 1595 that the bishop made his genuine capitulation. Henri left him in his bishopric, and he would remain there until his death in 1613.

Early life and family

[edit]

Urbain de Saint-Gelais was born in 1540, the illegitimate son of Louis de Saint-Gelais, the seigneur de Lanssac and Louise de La Béraudière.[1][2] His father had the affair while on military campaign against the Holy Roman Emperor.[3]

His father, Louis, enjoyed great royal favour, in particular with the queen mother Catherine. He was thus showered with royal honours.[4] He undertook numerous diplomatic missions including to the Council of Trent in 1562.[5] By the time of his death, Louis had amassed a fortune of around 64,000,000 livres (pounds). His favour was a great boon to his children, who found themselves raised proximate to power. Urbain's half brother, Guy de Saint-Gelais would enjoy many governorships and an important diplomatic mission.[2]

Urbain had ties with the Vivonne family of whom the baron de Saint-Gouard would serve as the French ambassador to Spain from 1572 to 1582.[6][7]

Urbain enjoyed an excellent command of both the Italian and Castilian languages.[2]

Urbain had illegitimate issue of his own:[8]

- Guy de Saint-Rys.[8]

Reign of Charles IX

[edit]Bishopric of Comminges

[edit]

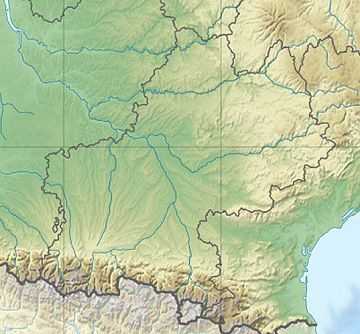

During the 1560s, the bishop of Comminges was Pierre d'Albret. He struggled in his diocese, suspicious to both the French monarchy and the Spanish crown. His own flock attacked him in his residence in Saint-Bertrand.[9] He resisted the prospect of conversion to Protestantism that his niece, the queen of Navarre Jeanne desired for him and her supporters chased him from the diocese. With the see vacant, it was preyed upon by the Spanish bishop of Urgell who sought to annex the Val d'Aran, a cross border component of the bishopric. There was a strong desire in Aran to remain within the bishopric of Comminges.[10] Through the two archpriests of Aran, the diocese held a presence inside Spain. Comminges at large was a firmly Catholic territory, wedged between the Albret lands of Béarn and Foix. Indeed, the Albret enjoyed suzerainty over several territories inside the comté de Comminges (the baronnie d'Aspet, Larboust and Nébouzan). Despite this Protestantism made little headway in Comminges.[11]

The queen of Navarre attempted to install the illegitimate son of her husband, Charles de Bourbon in the diocese. By this means, Charles de Bourbon received the revenues of the diocese according to letters patent issued by Charles IX in 1569.[12] He would not however be invested in it, and through the intervention of Urbain's father Louis de Saint-Gelais, and a letter of support from Charles IX recalling Louis de Saint-Gelais' deeds, Urbain became the bishop of Comminges in 1570 with the blessing of the Pope.[13][14][1] This greatly embittered the prince de Béarn (future king Henri IV, and half brother of Charles de Bourbon) who saw little reason the house of Saint-Gelais should profit at the expense of the royal house of Bourbon.[12] In compensation for his removal from the diocese, it was agreed that Charles de Bourbon would be paid 15,000 livres.[2] The queen mother, Catherine also promised the queen of Navarre that Bourbon would receive the bishopric of Lectoure.[12]

Bishop of Comminges

[edit]

The affection between the new bishop of Comminges and his diocese was fostered quickly. Before even the agreement of the king or the governor had been received the councillors of the Val d'Aran travelled to meet with their new bishop at his see of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges to gain recognition of their privileges and other agreements.[15]

The bishop of Comminges did not have a place in the provincial 'Estates of Comminges', the presidency of which belonged to the bishop of Couserans. Nevertheless, he would endeavour to appear before them on occasion.[16]

After Urbain adopted the mantle of bishop of Comminges, the Spanish king Felipe II ceased his efforts to peel off the Val d'Aran into the bishopric of Urgell in addition to his plans to introduce the Inquisition in Aran. This area would become a general exception to the Spanish policy of standardising the ecclesiastical boundaries alongside the political ones. Brunet suggests this might reflect an aligning of views between Felipe and the bishop of Comminges as early as the 1570s.[17]

In 1571 he succeeded to one of the two positions of conseiller-clerc (councillor-clerk) in the parlement (most senior sovereign courts of France) of Toulouse after his uncle the bishop of Uzès who had resigned the charge.[18][16]

In addition to his responsibilities in the parlement of Toulouse, he would request a role in those of Bordeaux and possibly Paris in 1572.[16]

The bishop of Comminges played host at his episcopal residence at Alan (Saint-Bertrand having been abandoned in favour of residences at Alan, L'Isle and Saint-Frajou at the termination of the medieval period as far as the bishops residence was concerned) to Spanish members of his diocese from the Val d'Aran in January 1574.[19][16] The bishop worked to court the Spanish members of his flock by intervening with Henri III to see that the Lies et passeries (local agreements made in the mountain border regions of France and Spain to guarantee common pastures, unified policing, the maintenance of commerce during war time and the combatting of threats to the peace).[20][21]

Reign of Henri III

[edit]During 1574, the governor of Toulouse, the baron de Fourquevaux appeared before the Estates of Languedoc. He had a scathing assessment of the bishops of the territory, who he decried as absentees interested in little more than idle pleasures. He noted that the bishop of Comminges was the only positive example, who was "in his sheepfold doing the office of a good shepherd".[22]

Early ligueur

[edit]The historian Brunet believes it likely that when the seigneur d'Ardiège engaged his marauding band in their first attack against the church of Eoux where the bishop of Comminges was to be found, in May 1575, that the bishop was in the process of raising a militia from the surrounds of Alan.[20] The bishop was meeting with the baron de Gondrin during the attack, one of his servants was killed, with the bishops mantle scorched in several places by arquebus fire. It was only thanks to the baron de Gondrin that the bishop of Comminges was saved.[21]

In 1576 a generous peace was reached between the French crown and the Protestant/Malcontent faction, bringing to a close the fifth French War of Religion. By its terms generous concessions were made to the Protestants. This inspired a hot reaction among militant Catholics who responded by the formation of a national Catholic Ligue (League). This Ligue opposed the peace, and compromise with Protestantism.[23][24][25][26]

One of the most committed ligueurs (leaguers) among the senior clergy, the bishop of Comminges had affiliated with the ligue since 1576.[27] Comminges' half brother, Lanssac, met with the duc de Guise (duke of Guise) and cardinal de Guise prior to the declaration of the ligue in Bourg. However, unlike his brother, any involvement Comminges had, was discreet.[20]

Portugal

[edit]

In 1579, the bishop of Comminges undertook an extraordinary diplomatic mission to Portugal and he travelled to Lisbon to this end.[28] Alongside him for the conduct of this mission was the royal favourite the marquis de Beauvais-Nangis.[1][29] The queen mother Catherine had recommended him to the king for this mission as a 'prelate of the church and a man of letters'.[5] His was not the only extraordinary diplomatic posting to Portugal in 1579, and the sécretaire (secretary) to the Spanish ambassador the baron de Saint-Gouard, the sieur de Longlée also undertook a mission in this year.[30] According to Carpi and Lhoumeau the purpose of the bishop's mission was to defend Catherine's rights as concerned the prospect of succession to the Portuguese throne.[31] This was through her descent from king Afonso III who had died in 1279.[32] According to the historian Le Roux the purpose of his mission was to advocate for the rights of the prior do Crato (prior of Crato), an illegitimate grandson of the Portuguese king Manuel and thus nephew of the current childless king.[33] Either way the bishop of Comminges' mission was not a success.[32] Brunet speculates that the bishop of Comminges' half brother, the seigneur de Lanssac might have had a role to play in the failure of his mission.[34] Lanssac had adopted an attitude that appeared contrary to Catherine's interests in favour of the Spanish king Felipe.[21]

Going forward from this time, Comminges would maintain contacts in Spain.[31]

When news arrived at the French court of the death of the childless king of Portugal on 15 January 1580, Catherine instituted a solemn funerary observance to take place at the Notre Dame. There were several pretenders seeking to succeed the old king to the throne, and prior to his death the king had not chosen any one of them. The regency council declared the competing claims of those seeking the throne would be examined. One of the claimants was the Spanish king Felipe II. He asserted his rights on both his kinship and feudal law - Portugal having been a county that was dependent on the kingdom of Castile (one of the constituent components of the kingdom of Spain). To be assured of his triumph he began assembling an army on the border with Portugal. Catherine selected the bishop of Comminges to be her avocat (lawyer) for the tribunal of the claims.[35] Felipe's army bested that of the prior do Crato in August, and the pretender would seek refuge in France in 1581.[33]

In June 1580, a request arrived with Henri from the premier président (first president) of the Parlement of Toulouse. In this, the président requested of the king that he maintain Comminges in his see. In his estimation to lose this bishop from Comminges would be to jeopardise the security of the province.[36]

Second Catholic Ligue

[edit]

On 10 June 1584, Henri's brother and heir, the duc d'Anjou died. Without a child, Henri's heir became his distant cousin the Protestant king of Navarre. The prospect of a Protestant succession to the throne was unacceptable to many Catholic nobles who re-founded the Catholic Ligue under the leadership of the duc de Guise.[37][38][39]

From 10 to 12 October 1584, the queen of Navarre, Marguerite travelled to Alan to stay with the bishop of Comminges. The historian Brunet suspects the two discussed the plan for the forthcoming ligueur insurrection.[40]

On 17 January 1585 a secret treaty was signed at Joinville between the duc de Guise, his brother the duc de Mayenne, their cousins: the duc d'Aumale, and duc d'Elbeuf and the seigneur de Maineville (a representative for the cardinal de Bourbon) for the ligueur nobility, and the Spanish ambassador to France and a commander of the order of Malta named de Moreo for the king of Spain.[18][41] Both the bishop of Comminges and his half brother the seigneur de Lanssac were important in the establishing of this alliance. [18]

The bishop of Comminges and his half brother had facilitated the passage of Moreo through the Val d'Aran and the comté de Comminges. They then received him in the family haunt of Bourg-sur-Gironde before he went on his way to Joinville to participate in the signing of the treaty. While he was in Bourg-sur-Gironde the men planned the coming ligueur uprising in the south-west of France.[42]

By the terms of the agreement Comminges and Lanssac had helped facilitate, the Spanish king recognised the ligueur candidate to succeed the childless Henri III, the cardinal de Bourbon as the heir to the French throne, he would also support the ligueur party in France to the sum of 600,000 écus (crowns) of which the duc de Lorraine would front 400,000. These two grants came at a high price. In return Felipe expected: the eradication of Protestantism in France, the adoption of the resolutions of the Council of Trento in the kingdom, the return of Cambrai to Felipe, that the cardinal de Bourbon agree to cede French Navarre and Béarn to Felipe, that France break off its alliance with the Ottoman Empire, that France cease to harass Spanish positions in the Caribbean, that France support Spain in crushing the Dutch revolt in the Spanish Netherlands, and that France hand over the pretender of the Portuguese throne the prior do Crato to Felipe.[31] Felipe may not have imagined that all of these points would be realised, but he hoped that he might weaken Henri III and dissuade him from military interventions.[31]

The pretence of continued ligueur loyalty to the French crown collapsed in March with the interception of a boat filled with arms intended for the ligue. Guise took control of Châlons and made a declaration on 20 March. This was followed with the issuing of a manifesto from Péronne (where the 1576 Catholic Ligue had originated) on 31 March.[43]

War with the crown

[edit]Comminges and his brother the seigneur de Lanssac drove the Catholic nobility to take arms with the aim of capturing Montauban, Castres and other Protestant held towns. There would indeed be ligueur operations undertaken at Castres. Lanssac would involve himself in several military efforts, though would find himself frustrated by the maréchal de Matignon (marshal Matignon - lieutenant-général of Guyenne). Despite the efforts of the ligueur party in the province, which also made efforts on French Navarre, Alet and L'Isle-Jourdain, the ligue failed to gain a strong foothold in Guyenne.[44]

The queen of Navarre was won over to the ligueur cause by Spain and the urgings of the bishop of Comminges. To this end she met with him in Alan prior to the start of her uprising.[36] After meeting with Comminges, she travelled to Agen in March and purged the city of those officers that were not loyal to her before assuming command of the city. From here she struck out in several military campaigns, though they were bested by the forces of her husband, the Protestant king of Navarre and by August she could no longer pay her soldiers, and the populations under her authority chafed under the impositions required of them.[45] As such, when Matignon was tasked with returning the city to royal obedience. He bribed several inhabitants of Agen who then effected a coup against Marguerite in September.[46]

The ligueur party in the south-west, chief among them the queen of Navarre, hoped to receive both financial and military aid from the Spanish king. However, the latter was not provided and even the former was deficient for the queen of Navarre's cause (forcing her to take refuge in Auvergne).[42]

During June 1585, according to the French ambassador in Spain the sieur de Longlée, the bishop of Comminges undertook diplomatic work between Spain and the Catholic ligue in the south-west of France.[47]

The bishop of Comminges fought for the cause in the Comté de Comminges (county of Comminges). With the support of the vicomte de Duras he engaged in seizures and pillage. In reaction to the offensive the bishop undertook his see of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges was captured and pillaged by the Protestant baron de Sus in 1586, something the bishop was unable to prevent.[48][36] The Aure-Larboust brothers would rush to join in on the sacking of Saint-Bertrand, seizing the archives and the treasury of the cathedral.[49][50] Catherine wrote to her son the king saying that he well knew 'what kind of people' the Larboust were.[51]

The bishop endeavoured to reconquer his see. To this end he gained the military support of the Montagnards of Haut-Comminges and bandoliers from Antonio de Bardaxí. The Bardaxí, members of the Aragonese nobility had as far back as the 1560s maintained connections between the French seigneur de Monluc and the Spanish court.[52] The bishop was also provided a cannon by the city of Toulouse, which had a decisive effect in his return to Saint-Bertrand. Along with a force of 500 arquebusiers and his summons from the countryside he laid siege to the city. After two months and three days of effort, Saint-Bertrand fell to its bishop on 13 June.[50] Those inhabitants who had left their homes with the Protestant conquest of de Sus returned. The campaign cost the bishop around 45,863 livres, of which 9,000 was paid off by the Estates of Comminges. Catherine, little realising the bishops' ligueur proclivities, was also sympathetic to his plight, and urged Henri to cover the bishop's expenses.[53] To cover the rest of his costs, he sought reimbursement from the lieutenant-général de Guyenne maréchal Matignon. In this account, he tactically minimised the role the militia's he had employed had played in the reconquest. King Henri was overflowing in praise for the bishop's recapture of Saint-Bertrand, and endorsed his request for reimbursement.[50] Brunet finds this demonstrative that the bishop's ligueur and Spanish sympathies were still unknown to the crown.[54]

The dislodged Protestant force turned their attentions to the rich episcopal fiefdom of Puymaurin. They would then have to be bought out of their control of Puymaurin for a dear price.[49]

In May 1586, the bishop was before the parlement of Toulouse. He harangued the body for its insufficient support for the Catholic faith in the diocese of Comminges.[55]

Brunet argues the affair of the reconquest of Saint-Bertrand evidences the precocious existence of the Campanère Ligue in Comminges. The noble seigneur de Montégut envisioned the adoption of a broad scale anti-Protestant ligue covering not only Comminges, but also the Condomois, Rieux and even Toulouse. In response to the ambitions of Montégut, the bishop of Comminges promised to bring together as many seigneurs, churchmen and towns as possible. On 11 July 1587, it was agreed at the Estates of Comminges to form a sworn association.[54] The nobility would be employed on both an offensive and defensive basis, the clergy (chief among them the bishops of Comminges and the bishop of Rieux) would offer fiscal support, and the common people would serve as the soldiery.[56]

Alongside the Spanish agent de Moreo and the duc de Guise, the bishop of Comminges was to be found in Antwerp in 1588.[57]

Estates General of 1588

[edit]Sometime between the Day of the Barricades in May and the meeting of the Estates General in October, the queen of Navarre addressed a long correspondence to the Spanish king. She proffered 2,000 cavalry and 12,000 arquebusiers to campaign in Guyenne and Languedoc (those provinces closest to the king and key for her husband).[42] With Spanish help she suggested she could seize Bordeaux, Bayonne and other centres. She suggested she could count on many allies in this fight, and offered Felipe two pathways. He could either declare himself openly in France or operate from the shadows behind a French seigneur (lord). The bishop of Comminges translated the letter and ensured its provision to Felipe. This time, the king was not ignorant of the bishops involvement in Marguerite's intrigues.[58]

Both the king and the ligueur party endeavoured to see their candidates sent as representatives for the Estates General of 1588. Neither side was afraid to employ less than legitimate means to see their choice sent to Blois. In Toulouse the ligue ensured the election of the bishop of Comminges and the avocat Étienne Tournier, with the former representing the First Estate, and the latter the Third. They replaced the bishop of Lavaur and Pierre de Rahou as representatives for the sénéchaussée (administrative division). The latter two men had been elected at a meeting of the sénéchausée on 5 September. However, it was subsequently declared that this meeting was irregular and had insufficient attendance, hence the supplanting of these men whose Catholicism was believed to be insufficiently robust.[59][53][60] Comminges was a representative of the sénéchausée of Toulouse as opposed to those of Comminges as his episcopal city was in the jurisdiction of Rivière-Verdun.[56]

The cahiers (summaries of grievances assembled for an Estates General) brought to the Estates were not particularly ligueur in construction.[60] Those of the city of Toulouse which survive illustrate various popular Catholic concerns, such as the endorsement of the Tridentine Decrees, the sale of Protestant land and the assuring that there would be no Protestant king should Henri die without an heir.[61] It was hoped that venal offices would be suppressed and the scale of the judiciary reduced to the levels it had been under Louis XII.[62]

Having been elected, the bishop would participate in the meeting of the Estates as a representative of the First Estate.[63]

Royal coup

[edit]

After the king's sudden strike against the ligueur leadership during the Estates General, in which he had the duc de Guise and his brother the cardinal de Guise assassinated, both Lanssac and the bishop of Comminges thought it prudent to hurriedly make their departure from Blois.[64] Indeed, Comminges' arrest was of interest to the king.[58] The bishop would flee alongside his friend, the bishop of Rodez.[65] The flight of Comminges from Blois made his allegiance clear.[53] Le Roux argues that while the bishop of Comminges flight from Blois is certain, Lanssac's is conjectural.[66] The bishop of Comminges took refuge in Toulouse.[67]

Toulouse

[edit]Bureau d'État

[edit]Word of the assassination of the duc de Guise and his brother the cardinal de Guise was brought to Toulouse on 3 January 1589 with the arrival of the bishop of Comminges and Rodez.[68] The bishop of Comminges brought with him an undated declaration produced by the Parisian ligueurs by which the Toulousian parlement was to announce its withdrawal of obedience to the king.[69] The bishop of Comminges endeavoured to spread the word of the assassination and inspire passions in response.[70] This ligueur narrative arrived in the city before the official royal narrative of the assassinations, much to the vexation of Henri, as his telling was subsequently little believed.[68] At the same time as Comminges arrived in the city, a letter was received from the Parisian ligueurs urging the city to subordinate itself to the duc de Mayenne (who had taken over the leadership of the ligue upon the murder of his brother - he would be established as ligueur lieutenant-général du royaume in February 1589).[71][72][73] Preachers expounded upon the wickedness of the tyrant king Henri and processions were organised. The bishop of Comminges had a key role to play in the ligueur coup that followed.[74]

Defensive measures began to be explored by the municipal magistracy on 6 January then on 7 January at the instigation of the grand vicar and provost of the cathedral of Saint-Étienne, Jean Daffis, a bureau d'État was established by the ligueur sympathetic Toulousians, composed of eighteen members (six clerics, six bourgeois - of whom two were Capitouls of Toulouse and six parlementaires) to deal with the most sensitive matters alongside the capitouls (municipal magistrate, akin to an alderman) of Toulouse.[67][75] The most important decisions would be referred to the premier président of the Parlement.[53] The bureau was endorsed by the parlement on 8 January.[71] Souriac argues that the formation of this bureau represented the unification of all the decision-making bodies that existed in Toulouse.[76] Also on 7 January, the sénéchal of Toulouse presented himself before the city with his compagnie (company). Alongside the bishop of Comminges he had been one of the representatives of the sénéchaussée at the recent Estates General. In addition he had demonstrated his Catholic fervour in years prior in the army of the duc de Joyeuse. However, at this time, the Joyeuse family, who he had served, remained loyal to the crown, further the sénéchal had arrived with instructions from the king. The capitouls in agreement with the parlement refused entry to the city to their sénéchal on the grounds his presence would be disruptive to public order. He was instructed to leave his messages from the king behind, and depart from outside Toulouse.[70]

The keys to the city were recast, and the captains of the capitoulate were re-selected by the new bureau. This latter measure was to the chagrin of the conseil de ville (town council) as responsibility for this selection had been the responsibility of the conseil de bourgeoisie.[71]

Enlarged council

[edit]Comminges served as one of the representatives of the bureau d'État. In the third week of January he denounced those bourgeois in the bureau he saw as politiques (those who prioritised the stability and order of the state over religious purity) and those around the premier président of the parlement Jean Étienne Duranti.[75] Duranti was in part disliked among the ligueur partisans of Toulouse due to his eagerness to learn of the heretical associations of notables of the city.[55] He had also engendered hostility by the increase of the guard he had instituted around his residence.[77] Comminges then proposed an enlarged town council be called so that they might withdraw their obedience from Henri III. Duranti first flatly opposed the council, fearing the seditions that might result from it. This was interpreted as a proof of his treachery. On 21 January he conceded to the calling of such a council but insisted it be limited to 100 bourgeois. By this means his authority was further compromised.[78][77]

This new wider assembly convened on 22 January and would spend the next three days in discussions, largely concerned with loyalty to Henri. The bishop put in an appearance at this council and raged against the politiques, a group in which he included Duranti. After a proposal to have the portrait of Henri III present in the parlements deliberation chambers removed the avocat général Jacques Daffis mounted a defence of the king, stating that any who committed treason against their sovereign would be subject to legal reprisals. The debate became very heated but the bishop of Comminges helped calm matters.[77] The session was prorogued by Duranti on the grounds they needed to seek the opinion of the parlement. Comminges enjoyed a position in the parlement that he had inherited in 1571 and thus he took part in this discussion. He took the opportunity to denounce the "huguenots, politiques, Épernonistes, Damvillistes et Matignonistes". All of the prior mentioned groups were to be arrested in Comminges' view. The lobby area of the parlement filled with armed men in support of Comminges' position and Duranti tried to terminate the session.[79] Comminges argued that closing the session without having reached a conclusion would excite popular violence, in this he was supposedly supported by the 'younger judges'. The body at large was sympathetic to the ligueur disposition[78] Comminges thus triumphed in this session.[80]

As Duranti was departing for his coach he was approached by a priest wielding a sword. When one of his guards struck the priest the latter cried out 'Aide a l'Églises' and a larger skirmish followed with weapons being thrust through the exterior of Duranti's carriage. [80]

Governor of Toulouse

[edit]In the evening, barricades appeared in many places in Toulouse and Duranti was forced to take shelter in the Hôtel de ville (city hall).[80] The people of Toulouse were exasperated by Duranti's attempts at stalling in the parlement and his palace was put to siege.[78] Comminges was not interested in fanning the flames of a class war, and alongside two other members of the conseil d'État worked to calm passions. To this end they undertook processions around the city.[80] When the procession reached the cathedral the following day, the mood turned sour again, and it was angrily demanded that all politiques be executed alongside men who put 'the cause of the Valois before that of Jesus'.[81]

The procession tried to persuade the bishop of Comminges to take the reins of governor of Toulouse and the sénéchaussée, something he would refuse them several times, before finally accepting the honour before the altar of Saint-Étienne. This acceptance was on two conditions, firstly that the nomination be endorsed by the parlement and secondly that it be of a provisional nature until the Sainte Union might select a proper prince for the charge. With the parlement already having conceded to the full meeting of the city, it could do little but endorse his nomination on the following day, 29 January.[81][78][82][83]

He took his oath of office on 4 February.[82] Notably the notion of a 'governor' had been anathema to the capitouls of Toulouse as in opposition to their municipal liberties when the governor in question was the baron de Terride, the baron de Fourquevaux or the seigneur de Savignac.[84] No such protests were made with the elevation of the bishop of Comminges. Souriac argues the nature of his elevation, by the most politically active ultra-Catholics of the city embodying a broader Toulousian consensus made it impossible to oppose.[85] Greengrass disputes this analysis of Souriac's and notes that in the infringement of the urban privileges of Toulouse caused two capitouls to resign their charges on 4 February.[81] The wages of the new governor were to be seen to by the trésoriers municipaux (municipal treasures), Puget and Le Balme.[71] He would take 500 livres a month to maintain himself.[82]

The bishop was determined to organise the ligueur cause in Toulouse.[63] Following in the mould of the maréchal de Monluc and the cardinal d'Armagnac, he established a religious brotherhood, known as the confrérie du Saint-Sacrament (brotherhood of the Holy Sacrament).[86] Little is known about this organisation, the only proper reference to it being in a later denunciation of Joyeuse's before the parlement.[87] Fairly unusually among the ligueur leadership, the bishop of Comminges enjoyed a strong influence with the common people.[88]

He would establish the first ligueur armies of Toulouse.[89] To support the small Toulousian ligueur army, the seigneur de La Balme was established as a trésorier extraordinaire des guerres (extraordinary treasurer of the wars) with the authorisation of the bishop of Comminges, the parlement and the capitouls.[90][91] Money was raised through the seizing of Protestant property, confiscations of the tithe, and loans to support this army. By this means the military force was to defend both Toulouse and its immediate surrounds, without being dependant on the consular administration of Toulouse.[92] Since the time of the governor Cornusson, compagnies imported into the city stayed there only for the preparation of their campaigns. However, this pattern was broken from in 1589 by the bishop of Comminges who brought in the Bérat regiment and some Gascon nobles. This represented an emergency mobilisation for the cities defence in a troubled year.[93]

It was only in the matter of the captaincies of the capitoulate that the new administrative apparatus found opposition from the existing structures of power in Toulouse. The historian Souriac argues that the local decision making framework continued to function much as it had done. Further that the balance of power in the city with its new governor Comminges, was not dissimilar to that with prior governors such as Bellegarde or Cornusson.[94]

Despite the ascendency of the bishop of Comminges in Toulouse, Henri opined that he maintained his faith in the nobility of Languedoc, who he believed would remain loyal to the royalist cause as long as they had a suitable leader.[95] Henri was also aware of what Comminges had been up to in Toulouse. He thus also wrote to the vicomte de Joyeuse (viscount of Joyeuse) - alternatively known as the maréchal de Joyeuse - on 23 February 1589 informing him that the bishop of Comminges had connections with the Spanish, including a man named Jehan de Bardachin (in Spanish Juan de Bardaxí), and that the bishop intended to bring the Spanish into the kingdom, delivering the province to them.[73] Henri proposed that the vicomte de Larboust and his brother should seize the revenues of the bishopric of Comminges, and then take the château d'Alan where they would find evidence of Comminges' guilt in illegally minting money.[96] Henri hoped to strike at the dîmes (tithes) which supported Comminges and had success on this front.[97]

Assassination of Duranti and Daffis

[edit]Passions between the ligueur and royalist party were approaching a high point. The ligueur party unified itself around the denunciations of politiques in the city who were accused of covert Protestantism.[74] These tensions reached a climax after it was discovered the avocat-général of the Parlement of Toulouse (Jacques Daffis) had been in contact with the royalist lieutenant-général of Guyenne the maréchal de Matignon and the président of the parlement of Bordeaux, Guillaume Daffis in the hope of receiving soldiers to restore control over Toulouse and oust Comminges.[78] Copies of the letters had been discovered by the bureau d'État.[79] Both Daffis and Duranti were opponents of the bishop of Comminges.[98][99][100]

After this episode the bureau d'État resolved to have Duranti and Daffis immediately arrested. With the protection of Comminges and the Jean VI de Fossé (bishop of Castres) he was transferred to the Jacobin convent.[78] The parlement did not want to prosecute the men and thus a mob of four thousand resolved to enact popular justice.[81]

On 10 February 1589, the two men were taken from the convent they were being held in. Duranti was dragged through the streets before being taken to the place Saint-Georges where he was hanged. A portrait of Henri III was affixed to his body.[101] Meanwhile, Daffis was murdered more summarily on the steps of the prisons of the parlement.[99][102] One of Duranti's servants was also murdered.[79] Duranti's residence, library and gardens were looted and burned. The following day his body was taken down by two of the capitouls who wrapped him in the canvass and buried him. The exact role of Comminges in the dual lynching is disputed, with the event either presented as a popular outburst, or one that was orchestrated by him. Greengrass concludes that all we can say is that as governor of the city it was ultimately his responsibility to ensure the maintenance of order.[102] The violence of the 'popular tribunal' by which Duranti and Daffis were lynched, would turn the parlement against the bishop's government and towards the vicomte de Joyeuse. For Comminges, the court had proven itself too timid and politique.[103] Despite the reputation they had earned with the radical party in 1589, Duranti and Daffis had previously enjoyed reputations as very firm Catholics.[104] Duranti had been a member of the ligueur party in 1585 alongside the bishop of Comminges and was a zealous Catholic. However, he had not abandoned Henri after the assassination of the duc de Guise.[105][98][102][103]

The heat of the political hatreds between the committed ligueurs and the politiques in the city was tempered by fearful memory of the Protestant coup in the city in 1562 and the presence of many Protestant held settlements around Toulouse.[100]

When Henri moving to relocate parlements from disobedient cities, Toulouse's parlement withdrew their obedience to his authority in February.[73] Henri ordered that the parlementaires vacate Toulouse in favour of first Carcassonne (declared on 17 June) and then Béziers (after Carcassonne fell to the ligue).[100] Only two members of the parlement heeded the royalist call.[106] This made the parlement perhaps the most uniformly loyal to the ligueur cause behind only that of Dijon. Some parlementaires travelled to neighbouring towns around Toulouse to secure their affiliation to the Sainte Union.[107] These missions had much success.[108]

Nevertheless, the ligueur government in Toulouse failed to impose itself on the wider ligueur movement outside of the city, during the bishop of Comminges brief ascendency.[109]

Following on from the lead of the Sorbonne in Paris, in March the theology faculty of Toulouse functionally declared Henri III deposed.[107]

Against Joyeuse

[edit]

After Henri III entered into alliance with the Protestant king of Navarre on 3 April, he restored the duc de Montmorency to the governorship of Languedoc.[110] This alienated the vicomte de Joyeuse who then defected to the ligueur camp along with his son the duc de Joyeuse.[67] Both men swore their ligueur oaths on 20 April 1589, and the duc de Mayenne established the vicomte de Joyeuse as ligueur governor of Languedoc, and his son as the lieutenant-général in his absence.[71] Affiliating with the ligue had been a difficult decision for the vicomte de Joyeuse, and he quickly found himself frustrated in his efforts against the royalists by the lack of financial assistance from Toulouse. Seeing him as an artefact of Valois rule, there was little desire to provide the support that was promised to be provided to the 'bon prince' Mayenne would dispatch.[111]

In his new role as governor of Toulouse, the bishop of Comminges came into conflict with the ligueur leadership of the duc de Mayenne and the vicomte de Joyeuse, who had previously served as lieutenant-général of Languedoc. These men were suspicious that the bishop of Comminges intended to hand over Toulouse to Spain.[83] Representatives from Toulouse requested Mayenne appoint a 'prince of his house' to lead the ligueurs. While for a time the duc de Nemours was hoped for, Mayenne looked to his step-son the marquis de Villars. Villars would indeed arrive in Toulouse in April but refused the charge when it was offered to him.[112] The rivalry between the vicomte de Joyeuse and the bishop of Comminges was a threat to the political accord that had been reached with the establishment of the bureau d'État.[76] The tension in the ligueur leadership of the province also came to the attention of the Spanish king Felipe. It contrasted with other provinces where a clear ligueur leader was able to emerge (Bretagne - duc de Mercœur, Normandie - comte de Brissac, Picardie - duc d'Aumale and others).[113]

The conflict between the partisans of Joyeuse and those of Comminges meant that 1589 saw a particularly rapid increase for the cities extraordinary finances.[114] The bishop of Comminges enjoyed the support of several bishops in exile who were resident in Toulouse: those of François Bonard (Couserans), Raymond Cavalésy (Nîmes), Castres and Lavaur in addition to other senior clerics.[108]

In April, Mayenne promised Toulouse that Nemours would be sent out to the city. This would be furthered in August with assurances that the prince would arrive before September was out. Nevertheless, Nemours never came and was dispatched to Lyon instead.[115]

The bureau d'État finalised on 13 April (according to Greengrass, though Brunet offers a different date) the list of suspected politiques they had been working on. Those on the list were to be taxed in proportion with their means for a total revenue of 8,000 écus.[116][102] Greengrass states that many of the names on the list were quite out of date, being based on previous lists that had been drawn up in the last few decades.[104] With many of the named figures dead or long since fled from the city, raising the sum was quite unrealistic.[117] The bureau d'État proceeded to undertake house to house investigations. A climate of suspicion and denunciations followed. The clergy fantasised that the sum raised might be sufficient to rebuild their churches.[118]

The vicomte de Joyeuse entered Toulouse in May and the capitouls of Toulouse were presented with a letter in which Joyeuse's commission was outlined: he was to be obeyed as if he were Mayenne.[112]

Mayenne complained that the bishop of Comminges, and the city of Toulouse, had failed to send any representatives to the ligueur estates of Guyenne in June. According to an anonymous memoir, Comminges hesitancy, either to attend or send a representative was due to his ignorance as to the attitude of Felipe towards the provincial Estates, he would be unable to attend without instructions from the king. A purge of the politique capitouls and nobles was also envisioned.[112] Around this time (May to June) Comminges made a request of Felipe in a couple of memoranda to provide 500 arquebusiers. These arquebusiers were to be integrated with militias under the command of the Catholic nobility, chiefly the seigneur de Tajan, the seigneur de Salerm and the seigneur de Bérat. This force would be able to effect the purge of the politiques.[112] Overarching command would be given to a Spanish military leader. Two thousand militiamen would be raised for this army in only three days according to Comminges.[58]

In a joint plan with the capitouls of Toulouse on 6 June 1589, the bishop of Comminges sought to establish a bureau des finances extraordinaires de Guyenne (extraordinary bureau of finances of Guyenne). This institution already existed for Languedoc. They hoped to establish this institution (with the approval of the parlement) in Toulouse, so that their city would receive all the revenues of Guyenne. On 17 June the bureau was duly created, comprising conseillers of the Parlement, two men of the church, and bourgeois Toulousians. Mayenne and the Parisian ligueurs would succeed in confining Toulouse to a minor fiscal role however.[119]

Embassies past back and forth between the bureau d'État of Toulouse and that of the capital. There was even ambitions among the ligueurs of Toulouse to receive financial support from the capital for the war against the 'four enemies' (Matignon, Montmorency, Ėpernon and duc de Ventadour). Efforts by the Toulouse ligueurs to bring matters to the attention of Mayenne's council of state for his attention were unsuccessful, and both he and the council largely ignored Toulouse.[115] The Midi (south of France) at large was viewed as a distraction by Mayenne at this time, who saw the strength of Navarre and the Protestant party as too severe in this region, therefore concluding the war against the royalists was to be won in the north of France.[120]

It would be Joyeuse that presided over the ligueur Estates in Toulouse.[121]

Ligueur civil war

[edit]On 1 August, Henri III was assassinated. In Toulouse the ligueurs greeted this with joy. They now recognised the cardinal de Bourbon as king under the name Charles X. On 22 August it was declared by the parlement of Toulouse that the penalty for recognising the Protestant king of Navarre (who now styled himself Henri IV) as king rather than Charles X was death.[121]

On 31 August, the vicomte de Joyeuse made a surreptitious truce with the duc de Montmorency, forced on him due to his finances being so poor that his army had dissolved.[111] By its terms, Montmorency largely recognised Joyeuse's authority in the province. When this was learned of by the Toulousians it was interpreted as a betrayal of the ligue.[121]

The vicomte de Joyeuse entered Toulouse with the remainder of his army in the final week of September. He received no greeting from the capitouls. [111] Joyeuse then moved to attack the position of the bishop of Comminges, appearing before the parlement on 30 September for the registration of his truce with the duc de Montmorency. This truce was difficult for the parlementaires to stomach, particularly in its reference to Montmorency as governor 'pour le roi' (for the king), something which appeared to recognise the claim of Henri IV to the throne.[122] The bishop of Comminges was likely among the parlementaires who opposed it.[87] During this session Joyeuse accused the bishop of covertly establishing a new ligueur association in his new confrère du Saint-Sacrament which was 'against divine and civil law'. Beyond this he suggested the bishop intended to usurp both political and military authority into his own hands so that he might deliver Toulouse to the Spanish. The président Antoine-Jean de Paulo rose to the bishop's defence, but the maréchal de Joyeuse resolved to besiege the parlement with his soldiers, demanding Comminges step down and dissolve the confrère.[121][123][87]

Likely under this military pressure the parlement took action against the confrère without suppressing it. It was declared that no new members could be recruited to its ranks. It was further declared that foreigners would have to leave Toulouse. By this means it was hoped Spanish agents and others not loyal to Joyeuse would be removed from the city. The bishop of Comminges was not ousted by this coup, but he now maintained his position at Joyeuse's pleasure.[121]

In trying to explain the betrayal of Comminges by the parlement, the historian Brunet sees several factors. The military pressure Joyeuse exerted, with control of forts and the port Saint-Étienne. The assassination of Duranti, and the threat of purges of the court was also an unnerving factor. He further suggests it is likely Comminges was preparing to hand over the city to the Spanish crown and that submission to a foreign monarch was a step too far for some parlementaires.[121] The bishop also exerted an influence over the common people that was unsettling to the men of the parlement.[124]

The vicomte de Joyeuse retreated to the residence of the archbishop (Toulouse was the see of his son the cardinal de Joyeuse). The bishop of Comminges meanwhile retreated to the Île de Tounis to lick his wounds with an army of artisans. On 1 October he preached a fiery sermon urging those assembled to "arm themselves for Jesus Christ" and then led a procession towards the palace, brandishing a sword and a crucifix.[125] Angry crowds of around 500 to 600 persons surrounded the archbishop's palace and denounced Joyeuse. The maréchal, after consulting with the capitouls was forced to flee the city, retiring to Balma (the archbishops summer residence not too far from Toulouse).[124][94][87]

After this episode, Joyeuse, along with the troops of his son, the duc de Joyeuse, established a blockade of the city.[87] Some parlementaires and members of the council had followed Joyeuse in departing, however the majority remained in Toulouse with the bishop and Paulo in denouncing Joyeuse for attempting to bring soldiers into the city.[126] Ligueur troops were summoned to provide help to the defence. The marquis de Villars thus made his way into the city.[124][83]

From his blockade, Joyeuse demanded the head of Comminges. In a general assembly inside Toulouse, featuring the bishop of Comminges, de Paulo and the marquis de Villars it was resolved to entrust the government of the city to Villars so that the situation might be resolved.[124]

Despite enjoying a level of military superiority by which he could have crushed Joyeuse, Villars did not take a military line, much to Comminges' disadvantage. Rather he allowed Joyeuse to retreat to Castanet and began negotiations.[124] Brunet argues that Villars' 'mediation' in fact reflected his commitment to Mayenne's mission to Joyeuse to see the bishop of Comminges banished from Toulouse.[127] Mayenne dispatched an agent for negotiations between the sides, as did the Pope.[117]

Governor no more

[edit]On either 20 or 27 November, an accord was reached between the besieging army and Toulouse by which the bishop of Comminges would be dismissed and the authority of the vicomte de Joyeuse recognised.[83] Comminges announced he would resign his government, but it would be a resignation in favour of the duc de Mayenne. That day Comminges departed from the city.[66][94][128] The day after Comminges' departure, two politique ligueurs arrived to sign a peace between Toulouse and the maréchal de Joyeuse.[124] Brunet argues that the defeat of Comminges and the Hispano-Ligueurs (Spanish-Leaguers) in Toulouse acted as a precursor to the destruction of the same tendency by the Mayenniste party in Paris after the murder of the Parisian président Brisson in that city.[129] Believing Comminges was to be handed over to Joyeuse, the Toulousians revolted, and Villars and de Paulo had to soothe them.[124]

The bishops' followers were not ready to go down as easily as the bishop, and in December tried to seize the palais. This loyalist force was then pushed back to the Île de Tounis before being defeated by a force from the palais and the maison consulaire.[94][128]

As 1589 drew to a close, the most militant ligueur bodies in Toulouse were suppressed by the new Joyeuse government of the city. These were the eighteen member bureau d'État which had been dominated by the bishop of Comminges and the confrérie du Saint-Sacrement that he had established.[100] Toulouse's government at large maintained continuity with how it had always functioned.[109]

The vicomte de Toulouse subsequently worked to maintain urban order in his conquered city.[100] In February 1590, commissioners arrived, sent by the duc de Mayenne to complete the pacification of Toulouse.[109]

No longer ascendant in Toulouse, Comminges wrote a defence of his government of the city in 1589. Going forward he would operate in the shadows, hoping to achieve his goals through means of espionage. His military participation would be limited to the defence of the ligueur cause in Comminges.[86]

Felipe dispatched a representative named Pedro Saravia as an assurance of his commitment to the cause.[56]

Ligue Campanère

[edit]Outlines of a movement

[edit]In Comminges the bishop enjoyed relations with the minor nobility of the Haut-Comminges.[130] He also looked to the local ecclesiastical authorities. Clerics themselves would only defend their churches against royalist attack, however they would also proffer their support to combatants. Particularly in the Haut-Comminges churches were made into fortified strong points. This climaxed in the Val d'Aran, where the churches were transformed into châteaux ecclésiaux (church castles). Meanwhile, in the Bas-Comminges the ringing of bells would serve as an advanced warning system of attacks. It is from the bell-towers that the Comminges ligue acquired its name - the Ligue Campanère (Gascon: Campanau - bell tower).[131] This Ligue Campanère would develop in 1591.[132] The term itself would not be used before March 1594, rather in correspondence with Felipe it was referred to as the Ligue Campanelle (with the same meaning).[133]

In the Estates, regulations were established for villages military organisation, with a chief to preside over each one while there would also be a general chief over the wider organisation (though the name was left blank). Rules of conduct were established with those who violated them to face the justice of the ligue.[134] The territories under the authority of this Ligue Campanère did not map exactly to the borders of Comminges, including communities in the territory of Rivière-Verdun.[135]

The bishop of Comminges' role in the establishment of the Ligue Campanère is laid bare by the three epicentres of the movement. His see of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, Alan (the site of his episcopal château) and the rich lands around Puymaurin. He would only serve as its 'protector' however, and refused to be its official leader.[132] Though it would be compared with the Croquants movement in Limousin, it claimed representation among all three orders (clergy, nobility, commons).[72] In a further differentiation from other rebel peasant movements, those of the Campanère were anti-peace, and worked with the ligueur nobility to prosecute the war against the 'heretic king' Henri IV.[136]

While the ligue received the approval of the parlement of Toulouse and the ligueur lieutenant-général of Guyenne, it would not be until January 1592 that the Estates of Comminges gave their approval.[132] During a meeting of the Estates of Comminges at L'Isle-en-Dodon on 14 January 1592, the ligue was approved over the objections of the royal judge Sébastien de Cazalas. Those parishes that refused to register would be considered enemies.[97] They declared that the organisation under the particular protection of the bishop of Comminges. He would provide his moral authority while the marquis de Villars took the command of governor.[137]

Diplomat in Madrid

[edit]

During 1590, the bishop spent some time in Picardie alongside the ligueur prince, the duc d'Aumale.[57]

The Spanish king, Felipe, was insistent on the need for the endorsement of the provincial Estates, refusing to send soldiers into France without the taking of such a step. As a result of this, the bishop of Comminges prodded the marquis de Villars to undertaken negotiations with the Estates of Guyenne both to acquire more troops directly, and to endorse a mission to Felipe to acquire more soldiers still.[138] Therefore, the marquis de Villars ordered the convening of the provincial Estates of Guyenne, to meet at Gimont on 23 May 1590.[139] While full records of the meeting are lacking, it was agreed to support the ligueur war effort, for the preservation of Catholicism. To this end the clergy would sacrifice a portion of their tithes to pay for soldiers. Such funds did not stretch sufficiently however, and thus the bishop of Comminges was tasked with meeting Felipe, and requesting 4,000 infantry and 450 cavalry with pay for four months. These troops would pass through the Val d'Aran and Comminges.[127] There was concern that the Spanish soldiers might be ill disciplined, and therefore it was requested that they be well trained.[140][141][142]

Aware of the effort of the estates of Guyenne to receive Spanish support through Guyenne, the maréchal de Matignon (royalist lieutenant-général of Guyenne) visited Comminges in May 1590. He endeavoured to exploit opposition to the ligue that he picked up on in the comté, chiefly from the town of Salies. He further enjoyed the support of a member of the Estates of Comminges (a syndic named Baptiste de Lamezan).[143] At a meeting of the Estates of Lombez back in February, Lamezan helped lead the assembly to the possibilities of considering a truce with Matignon, or submitting to his authority.[144] The Estates of Comminges were brought closer to the ligue by the meeting of the Estates of Guyenne that transpired in May.[144]

On route to the Spanish court, the bishop of Comminges had intended to review the defences and soldiers of the upper-Garonne valley. However, this did not come to pass, due to the spread of an epidemic in the region.[145]

During the absence of the bishop, Villars was in Comminges to protect the province from the intrusions of Matignon. He compelled the submission of Saint-Gaudens to the ligue and then placed a client of the bishop of Comminges, named the seigneur de Luscat (who had been entrusted by the bishop with the guard of Saint-Bertrand) in charge of the place.[144]

Having received the bishop, Felipe dispatched Joaquim Claros to get a sense of the hostility in France between the party of Joyeuse and that of the bishop of Comminges.[113]

The bishop was in Spain from July until the end of 1590. He endeavoured to see soldiers sent so that they might resist the royalist forces of the duc de Montmorency and maréchal de Matignon. In August 1590, 6,000 Spanish soldiers were duly provided, entering the kingdom at Port-la-Nouvelle near Narbonne and providing the support the vicomte de Joyeuse required to fend off Montmorency and the seigneur de Lesdiguières.[146] Felipe promised also an army of intervention into Guyenne, and to this end began assembling soldiers in Aragón.[147]

In September the bishop presented to Felipe a letter from the marquis de Villars and several of the diocese of Gascogne.[144] Villars also dispatched his own representative Pedro Saravia to thank the king for his provision of soldiers and assure him of the loyalty of the nobility to the Catholic cause.[148]

While Comminges was absent from France, his colleague from the Estates General, Tournier, attempted to effect the purge of the parlement of Toulouse that he had envisioned. The plot was uncovered in September 1590 and Tournier, having barricaded himself on the Île de Tounis was forced to capitulate.[149]

Comminges' grand plan

[edit]Moving beyond the mandate he received from the Estates of Guyenne, the bishop of Comminges presented a grandiose plan to the Spanish king on the Garonne axis through the intermediary of Saraxia. The plan was only one part of a broader memorandum which also featured contributions by others, such as father Basile who opined that Villars was inexperienced, and Comminges was devoted to the Catholic cause but suffered from an over abundance of ambition and was liable to promise more than he could fulfil.[150] In the part of the memorandum produced by Comminges, the bishop proposed a plan by which both Bordeaux and Toulouse would be carried for the Spanish crown. The plan bore similarities to one proposed by the Breton ligueurs to Felipe.[148] Both Lanssac and Comminges held influence in this region. For the seigneur de Lanssac his seigneurie was close to Bourg on the confluence of the Garonne and Dordogne, for Comminges he enjoyed control of the abbey of Bourg.[151]

The bishop outlined the path of the Spanish invasion to the sovereign. They would enter the diocese of Comminges through the Val d'Aran, then head down the Garonne to first Toulouse and then Bordeaux. Comminges assured Felipe that he would have 12,000 disciplined soldiers to join with the Spanish contingent (i.e. the Campanères). Bourg-sur-Gironde was in the hands of Lanssac, and the other key citadel that controlled access to Bordeaux was Blaye, held by the seigneur de Lussan who Lanssac intended to bribe thereby bringing him over to their cause. Further to this, Marmande was held by the baron de Castelnau, Agen by the seigneur de Caupėne and various other strongpoints were held by men of the bishops network.[149] By this means a Spanish force would be landed like had been accomplished at Le Blavet in Bretagne to see to the reduction of Bordeaux.[150]

In Comminges opinion, the nobility of Guyenne were all driven by pecuniary concerns, and it would be necessary for Felipe to provide pensions suitable to the dignity of the nobles in question. He contrasted the situation in Guyenne, where the nobles could be dealt with in this way, with Languedoc where in his estimation there were no nobles of note to treat with, and rather it would be the urban consulates with which the Spanish had to negotiate. Comminges and the marquis de Villars envisioned the provision of supplies for the invading Spanish armies, both in terms of victuals and powder.[152] Villars announced that Spanish soldiers would be entering Comminges to the Estates of the province on 20 September. In return for offering such resources to the Spanish, the Estates of Comminges hoped to receive the liquidation of the Protestants of Foix and L'Isle-Jourdain. Villars meanwhile fancied himself the commander of the Spanish forces in France.[152]

The bishop of Comminges asked for the provision of 1,000 ducats so that two cannons might be forged for his bishopric of Saint-Bertrand (due to its control of the Garonne) and a further 2,000 ducats to garrison the place. In regards to broader policy, Comminges opined that the people should be appeased through the reduction of the ordinary tax burden (no more than 40,000 écus for Guyenne and Gascogne). In addition to the appeasing quality, it would allow for the easier collection of the dîme and revenues could instead be farmed on river traffic, which would bring in one million d'or in Comminges estimation.[147] It would be this policy of light ordinary taxation that the Spanish agent Mendoza represented with the Seize when he met with them in Paris.[153]

The mission of the bishop to the Spanish court was, in the estimation of the historian Brunet, blessed with a degree of conviviality, slickened by the bishops strong command of the Castilian language. Beyond this Felipe had promised the hoped for military interventions.[147]

Ligueur estates of Agen

[edit]Arriving back in the Val d'Aran on 8 January 1591, the bishop undertook the inspections of the region that he had intended to undergo prior to leaving for Felipe's court. He signed a concordat and liaised with the local militia captains.[154] He was accompanied by many captains from the Haut-Comminges on route to the ligueur estates that were convened at Agen. He was to inform these deputies of the imminent arrival of Spanish aid.[155] As he was departing from Aran back into France through the pass of Saint-Béat in February, his party was intercepted by a Béarnais (i.e. royalist) force directed against him by the regent of Béarn, Catherine. The fort of Saint-Béat which commanded access to Spain through the Val d'Aran was a target for Catherine.[149] Thanks to the captains that were with him the royalist ambush was forced back to the château de Cier-de-Luchon.[154][155]

One of the captains with him, Barbazan subsequently led a successful siege of Cier-de-Luchon, with the royalist captain who had led the ambush and several others being executed after its conclusion.[156] Meanwhile, Comminges passed through the comté de Comminges in safety on his way to Agen. This safety would not be replicated in Gimont or L'Isle Jourdain.[156] A bloody engagement was fought against some royalist garrisons in which three of Comminges' party were killed and a further five wounded, while the royalists who had assaulted them lost thirteen dead and twenty one wounded. Despite this, Comminges was able to reach Agen on 23 February for the ligueur estates. The royalist estates of Guyenne were being held simultaneously in Lectoure.[157]

The same day as Comminges arrived at the Estates, he wrote to the Spanish secretario (secretary) Idiáquez outlining the ideal route for Spanish aid to take into France. Specifically he proposed the Port de la Bonaigua which would be a longer route with worse roads, but would allow the force to draw up together without risking enemy attack. Brunet judges his proposed route to have been the most sound. The estates of Comminges were to provide the money for the logistical support in the operation.[158]

Waiting for the Spanish

[edit]Word of the imminent Spanish arrival was greeted with delight in Agen. Matignon was declared to be deposed, and the duc de Mayenne was urged to elevated the marquis de Villars to the post of governor of Guyenne. An army of 3,000 arquebusiers and 600 horsemen was to be raised for Villars.[159] Villars with enthusiasm took on the role, even before letters patent (by which Mayenne gave him the powers of governor if not the title) in his favour had been published. Meanwhile, in the royalist estates of Lectoure, subsidies were voted on and defensive preparations agreed to combat a Spanish invasion.[157]

Back in Alan, the bishop of Comminges made the friendly offering to the Spanish king of the acquisition of fish and birds for the king's palace at Aranjuez, which was then under construction.[147] His episcopal château d'Alan would not be subject to threats despite its ill-secure position.[130]

It would be the family of Aure-Larboust, also nobles of the Haut-Comminges but royalist rather than ligueur, who would particularly confound the plans of the bishop of Comminges over the coming years due to their influence in the region.[160]

In March 1591, Felipe intended to assume control of the condato de Ribagorza (county of Rbiagorza) on the Franco-Spanish border.[145]

Villars entrusted the bishop of Comminges with the mustering of soldiers to fight the royalists in Comminges. The royalists threatened Nébouzan, Samatan, Saint-Plancard and Montaut. With active combat in the region, Mayenne came south to undertake a siege of Monségur. The Comminges militia was active under the authority of the bishop and were further enlivened by the coming arrival of the Spaniards. Villars saw to the conquest of Fleurance, Cologne, Touget and Puycasquier.[159]

Depots for the Spanish troops were set up in Samatan, L'Isle-en-Dodon and Aurignac. The expenses of this could not be supported by the grants offered in the Estates of Guyenne and therefore the province of Comminges would be expected to contribute (though Villars consented to reducing the rate). The Estates of Comminges agreed to support Villars' army in its operations throughout Guyenne through payment of the octet tax.[161] The Estates begged Villars to support local garrisons in Comminges out of the general Guyenne treasury, however he refused, leaving the Estates to turn more towards the local rural ligueurs. He agreed to ensure the Spanish would be a disciplined force, and would not enter towns loyal to the ligue in Comminges.[162]

In 1591, Comminges made an appeal to Spain for a military intervention into southern France across the central pyrénées.[163] By this means he hoped the Protestant strongholds that menaced Toulouse would be reduced, and then the army would move on to capture first Bordeaux, then go on to Bretagne.[146] The contact between the southern leaders of the ligue and Spain is described as 'intense' by Souriac at this time.[164]

From May 1591, Comminges half-brother the seigneur de Lanssac was in Spain making a grandiose pitch to the king for a Spanish annexation of Guyenne and Bretagne.[165] Having failed to get an endorsement for his project he retired back to France to join with the bishop in Alan.[166]

Comminges and his half-brother Lanssac would receive a pension of 2,400 livres from Felipe.[4]

On 1 June 1591, the marquis de Villars announced to the Estates of Comminges that he was departing from the province. Command in his absence was left in the hands of a local: the capitain de Savignac. The bishop of Comminges shared in Villars' mood of optimism, opining that the tranquillity was such he did not feel the need to bother the Spanish crown with the news.[167]

The bishop of Comminges wrote directly to Felipe on 17 July, something he did only rarely. In this letter Comminges endeavoured to hurry along the Spanish provision of aid into France. The Protestants, who he had imagined would be exterminated, were rather alleged to be preparing an attack against the harvest collection.[168]

There was a divide in the ligue between the Hispano-ligueurs typified by the radical Parisians who in 1591 wrote to Felipe asking him to take the crown of France under his protection, and the Mayenniste party that would subsequently suppress the radicals in the capital during December 1591 with great brutality.[169] The bishop referred to what the historian Descimon has termed the Mayenniste party as politiques.[51] Mayenne's crushing of the radicals in Paris in December would entirely discredit him in the eyes of the bishop of Comminges. The bishop also identified in a letter in November 1591, a third party, those who saw one of Henri IV's Catholic relatives as the proper candidate for the throne. For Comminges, this group was bringing to Henri IV the neutral Catholics.[105][170] The bishop of Comminges was a Hispano-ligueur.[146][164] Comminges opposed the pretensions to the crown embodied by the duc de Mayenne, and advocated for the candidacy of the Spanish infanta (princess) Isabel Clara Eugenia. To this end he suggested to Felipe that he (Comminges) write in favour of her claim and the invalidity of Salic Law (the French agnatic laws of succession) under a foreign pseudonym.[147] He wrote to Felipe several times urging him to convince Mayenne to back down from his claims. He further wrote against the principal of Salic Law as having relevance for determining succession. In addition to writing to Felipe, he also wrote to the estranged wife of Henri IV, Marguerite, urging her to support the Spanish infanta's claim.[86]

Revolt of Aragón

[edit]

The province of Aragón in north-eastern Spain had traditionally enjoyed many liberties. When in 1591, Felipe attempted to have a former minister of his named Antonio Pérez, who was hiding from him in Aragón, charged by the inquisition, the people of Zaragoza rose up in rebellion to free Pérez. Felipe looked to send an army from Castile to crush this nascent rebellion.[171] There is debate about whether the army that Felipe raised was initially intended to fulfil his promise to the French ligueurs before being then redirected towards dealing with the revolt, or whether it was always intended for the revolt. Brunet finds far more evidence for the former hypothesis.[172][146]

An army gathered under the command of Alonso de Vargas combining 800 veterans of the Invincible Armada and 15,000 militiamen for an invasion of France. From Ágreda they were instructed to march on Zaragoza, to Vargas' annoyance. This force entered Zaragoza on 12 November and began a harsh repression. The distraction of this large force from entering France at a crucial moment in the fortunes of the royalist party saved the cause of Henri IV in the eyes of the historian Cloulas.[172][146]

In the eyes of the bishop of Comminges, the hands of the regent of Navarre, Catherine were to be seen at work in the revolt in Aragón, and even desired to see it spread to Catalunya. Suspicious of Béarnais merchants, the bishop advised Villars and the parlement of Toulouse that only agents of the Spanish crown should be allowed to cross the border between the kingdoms.[173]

The bishop of Comminges connected through the people of the Val d'Aran with the Spanish commander Vargas and the army of occupation in Aragón.[142] While they hoped the occupation force would cross the Pyrénées it would never do so.[174]

Catherine did indeed, as Comminges anticipated, intend to stoke the flames of the revolt in Spain through control of parts of Comminges and the Val d'Aran. She looked to resecure the châteaux de Saint-Béat and Cier-de-Luchon by which Spanish soldiers would be prevented from entering the kingdom. From here she would seize on the Spanish side of the frontier, the site of Castèth Leon.[173] In the assessment of the bishop, this was not a prelude to a broader scale invasion of the kingdom, but rather the royalists hoped that by securing these places they would for very little investment frustrate Felipe's cross border plans (as it was challenging to bring to bear artillery and large armies in that region).[175]

Felipe was tied down by both revolts in the northern provinces of Spain and the bankruptcy of his kingdom. Souriac makes the further point, that given the state of the southern provinces of France, a Spanish army of more than 30,000 was logistically impractical, even with the promises of ligueur support. This view was indeed held by Vargas' second in command Francisco de Bobadilla who believed it would be challenging to maintain an army in impoverished land.[176] He thus characterises the appeals for Spanish intervention, more as an artifice of rhetoric than a practical invasion plan.[164]

During this period the bishop of Comminges once again assumed the role of a man of war with the authority invested in him by Villars. He approved the raising of arquebusiers which travelled to Lombez to arrest Protestants who had come from Béarn. Two royalist compagnies under the command of ten captains approached with the intent of seizing Saint-Béat and Cier-de-Luchon. This was foiled, and subsequently the château de Cier-de-Luchon was torn down. It was agreed that 300 men of the Val d'Aran would aid in the defence of Benasque.[175] Alongside two commanders in whom he placed confidence, the bishop of Comminges oversaw the distribution of soldiers and the fortification of key points. He advised scaling down the 35 soldiers to be found in Castèth Leon to 20 due to its central place in the valley.[177]

When the commander Bardaxi attempted to bribe the sergeant in command of Castèth Leon, the bishop of Comminges had him dismissed. He further tried to assure himself of some Spanish cavalry, even if he understood the many body of the Spanish army was occupied crushing the revolt.[178] His main force would comprise a levy of montagnards while regular troops would simply support this force.[179]

The Ligue Campanère showed itself hostile to the network of châteaux in the region and worked towards their destruction.[180] The ligueurs reduced the former system of Castellanies in Comminges to a tax district, though even this was liable to be subject to challenge.[181]

In April 1592, the brother of Villars, the marquis de Montpezat conducted a mission into Aragón to request military support. The royalists thus feared that come the summer an army of 12,000 would cross the border in favour of the ligue under Villars' authority.[182]

The bishop wrote to the ligueur duc d'Aumale in 1592, who was operating in Picardie, to provide him comfort.[86]

Further debate was held in the Spanish court as to the feasibility of an invasion of southern France during 1592. In July, Felipe came back around to the idea of invading southern France. Rather than Comminges this would be through an invasion of Basse-Navarre in the west and another operation with Joyeuse in the east. By the end of August 1592, Felipe had abandoned this plan, resolving to maintain his force in Aragón.[176]

On 20 September 1592, the duc de Mayenne established the marquis de Villars as the ligueur lieutenant-général of Guyenne. Despite being his son-in-law Mayenne was cautious about the prospect of investing Villars with the full governorship of Guyenne.[174] Subsequently, Villars invested the bishop of Comminges with the authority to 'wage war on the enemy' with a group of hommes d'armes (men-at-arms).[86] Villars himself fantasised about being the leader of the Spanish army that would cross the Pyrénées, he lacked much of a military reputation however.[174]

Much to Comminges' irritation, the marquis de Villars decided to employ the Ligue Campanère in November 1592 for a purpose external to the local defence if Comminges, i.e. the capture of Tarbes for the ligue and the invasion of Bigorre (a territory over which Henri IV was comte). The ligueurs were open to this, despite the opposition of the bishop of Comminges.[182] The bishop desired the organisation to remain in Comminges for local defence.[132] Villars created much of the apparatus of a campaigning army, including surgeons and bakers. The offensive mission was a success, Ibos was seized and Pontacq put to siege.[183] Nevertheless, no Spanish invasion resulted.[184]

Conversion of Henri

[edit]