Uprising of Ivaylo

| Uprising of Ivaylo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Byzantine–Bulgarian wars | |||||||

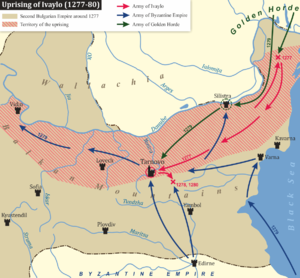

Bulgaria in the late 13th century. The area of Ivaylo's uprising are marked with red dots. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Bulgarians under Ivaylo |

Bulgarian nobility Byzantine Empire Golden Horde | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ivaylo of Bulgaria † |

Constantine Tikh † Ivan Asen III Michael VIII Palaiologos Nogai Khan | ||||||

The Uprising of Ivaylo (Bulgarian: Въстанието на Ивайло) was a rebellion of the Bulgarian peasantry against the incompetent rule of Emperor Constantine Tikh and the Bulgarian nobility. The revolt was fuelled mainly by the failure of the central authorities to confront the Mongol menace in north-eastern Bulgaria. The Mongols had looted and ravaged the Bulgarian population for decades, especially in the region of Dobrudzha. The weakness of the state institutions was due to the accelerating feudalisation of the Second Bulgarian Empire.

The peasants' leader Ivaylo, said to have been a swineherd by the contemporary Byzantine chroniclers, proved to be a successful general and charismatic leader. In the first months of the rebellion, he defeated the Mongols and the emperor's armies, personally slaying Constantine Tikh in battle. Later, he made a triumphant entry in the capital Tarnovo, married Maria Palaiologina Kantakouzene, the emperor's widow, and forced the nobility to recognize him as emperor of Bulgaria.

The Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos tried to exploit this situation and intervened in Bulgaria. He sent Ivan Asen III, son of the former Emperor Mitso Asen, to claim the Bulgarian throne at the head of a large Byzantine army. Simultaneously, Michael VIII incited the Mongols to attack from the north, forcing Ivaylo to fight on two fronts. Ivaylo was defeated by the Mongols and besieged in the important fortress of Drastar. In his absence, the nobility in Tarnovo opened the gates to Ivan Asen III. However, Ivaylo broke the siege and Ivan Asen III fled back to the Byzantine Empire. Michael VIII sent two large armies, but they were both defeated by the Bulgarian rebels in the Balkan mountains.

Meanwhile, the nobility in the capital had proclaimed as emperor one of their own, the magnate George Terter I. Surrounded by enemies and with diminishing support due to the constant warfare, Ivaylo fled to the court of the Mongol warlord Nogai Khan to seek aid, but was eventually murdered. The legacy of the rebellion endured both in Bulgaria and in Byzantium. Years after the demise of the peasant emperor, two "Pseudo-Ivaylos" appeared in the Byzantine Empire and enjoyed wide support by the populace.

Background

[edit]Political situation of Bulgaria

[edit]After the demise of Ivan Asen II (r. 1218–1241), the large Bulgarian Empire began to decline due to a succession of infant emperors and internal struggles among the nobility. To the north the country faced a Mongol invasion in 1242 and constant raiding thereafter. Although Ivan Asen II defeated the Mongols shortly before his death,[1] the regency of Kaliman I Asen (r. 1241–1246) agreed to pay an annual tribute to the Mongols to avoid devastation. The Mongol invasion led to the collapse of the loosely held Cuman confederation in the western part of the Eurasian Steppe and the foundation of the Mongol Golden Horde. This had long–term political and strategic consequences for Bulgaria — the Cumans were Bulgarian allies and often supplied the Bulgarian army with auxiliary cavalry, while the Golden Horde proved to be hostile.[2] To the south, Bulgaria lost large portions of Thrace and Macedonia to the Nicaean Empire, which had escaped the initial Mongol attacks.[3] The lands to the north-west, including Belgrade, Braničevo and Severin Banat, were conquered by the Kingdom of Hungary.[4]

In 1256, Bulgaria descended into a civil war between Mitso Asen (r. 1256–1257), a relative of Ivan Asen II, who established himself in south-eastern Bulgaria, and the bolyar of Skopje Constantine Tikh (r. 1257–1277), who was proclaimed emperor by the nobility in Tarnovo. Simultaneously, the Hungarian noble of Rus' princely origin Rostislav Mikhailovich established himself in Vidin as another claimant of the title Emperor of Bulgaria and was recognized as such by the Kingdom of Hungary.[5][6] By 1261, Constantine Tikh had emerged as victor, but his 20–year reign did not bring stability to Bulgaria: Vidin remained separated from the central authorities in Tarnovo,[7] and the Mongols regularly campaigned in north-eastern Bulgaria, looting the countryside and paralysing the economy.[8] That same year, Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1259–1282) seized Constantinople and restored the Byzantine Empire as a major adversary of Bulgaria to the south. In the 1260s, Constantine Tikh broke his leg in a hunting incident and was paralysed from the waist down.[9] This disability weakened his control over the government and he fell under the influence of his second wife, Irene Doukaina Laskarina, who was constantly involved in intrigues with her relatives in the Byzantine court. Later, he left state affairs to his third wife, Maria Palaiologina Kantakouzene — a scandalous intriguer whose actions to secure the succession of her son alienated the nobility.[9][10][11]

Internal situation and rise of Ivaylo

[edit]

The internal political development and feudalisation of Bulgaria in the 13th century resulted in a rising number of serfs, as well as an increase in the power of the landed nobility. This led to aspirations for more self-rule among the most influential nobles. Many of them established semi-independent fiefdoms that nominally recognized the emperor in Tarnovo and greatly reduced the capacity of the central authorities to deal with external threats.[12] In the second half of the 13th century, the peasantry was losing personal privileges to the benefit of the secular and religious feudal lords, which in turn reduced the peasants' income and opportunities, worsening their lives.[13][14] In parallel, the inability of Constantine Tikh to end the constant Mongol incursions in the north-east of the country shattered the pillars of the state institutions in Dobrudzha and contributed to the outbreak of the uprising and its swift success.[13] The Mongol raids were carried out by the semi-independent chief Nogai Khan, who was more powerful than the legitimate ruler of the Golden Horde, Mengu-Timur (r. 1266–1280), and ruled over the steppes of modern Moldova and Ukraine.[9]

Ivaylo, a native of north-eastern Bulgaria, most likely the area near Provadia,[15] began to incite the population to revolt. He was called by the contemporary Byzantine chroniclers by the name Bardokva (lettuce) or Lakhanas (vegetable) and his real name is known only from a note attached to the Svarlig Gospel.[13][16][17][18] The Byzantine historian George Pachymeres stated that he was a swineherd who took care of pigs for money.[19] However, historian John Fine notes that pigs were a major livestock product at the time and the possessor of a large herd could have been part of the elite of the local community.[9] Ivaylo claimed that he had visions from God to lead the people and that he was in contact with heaven and the saints.[9] In fact, his mysticism was deliberately used to swiftly gain support and followers among the religious villagers.[15][20] He came to be seen by many Bulgarians as a God-given saviour.[9]

Course of the rebellion

[edit]Initial victories

[edit]Lakhanas engaged a Mongol falanga, attacked it with the men he led, crushed them thoroughly and again attacked another unit. Thus, in a few days he covered with glory.[21]

— George Pachymeres on the victory of Ivaylo over the Mongols.

The rebellion broke out in the spring or summer of 1277 in north-eastern Bulgaria where the Mongol devastation was strongest.[22] In the summer of 1277 Ivaylo confronted and defeated a plundering Mongol unit. Another victory followed soon and by autumn all Mongols were driven out of Bulgarian territory.[23][24] Having achieved what had eluded the Bulgarian arms for decades, his popularity and reputation rose quickly. Among his followers were an increasing number of nobles who were discontent with the intrigues of Empress Maria.[9] Ivaylo was hailed as emperor by the people and many regions came under his control.[23]

In the end of 1277, Constantine Tikh finally took measures to confront the rebels. He gathered a small army and advanced slowly as he had to travel in a chariot because of his injury. Ivaylo attacked and defeated this force, killing many of the emperor's close associates, while the rest of the army joined the rebels. Ivaylo personally slew Constantine Tikh, claiming that the emperor did nothing to keep his honour in the battle.[25][26] After his triumph, Ivaylo began to seize the country's fortified cities, which surrendered and recognized him as emperor one by one. By the spring of 1278 only the capital Tarnovo remained under the control of Empress Maria.[27]

Byzantine intervention and recognition of Ivaylo

[edit]

Meanwhile, the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos left Constantinople for Adrianople, situated close to the Byzantine–Bulgarian border, in order to monitor the events and to exploit the situation in Bulgaria in his favour.[25][27] The demise of Constantine Tikh came as a shock to the Byzantines. Initially, Michael VIII considered marrying off his daughter to Ivaylo, but eventually decided it more favourable to install a protégé of his own.[20] His candidate was Ivan Asen III, son of the deposed Mitso Asen, who had sought asylum in Byzantium and possessed estates in Asia Minor. Ivan promptly married Michael VIII's daughter Irene, pledged allegiance to Michael VIII and was proclaimed emperor of Bulgaria.[28][29] The Byzantines sent gifts to the Bulgarian nobles to incite them to support Ivan Asen III and envoys were dispatched to Tarnovo to arrange for his recognition and the surrender of Empress Maria.[27] Meanwhile, Ivan Asen III marched north at the head of a Byzantine army while Ivaylo was besieging Tarnovo.[29]

Faced with two adversaries, Maria initially tried to negotiate with Michael VIII the succession of her son, Michael Asen II, but the Byzantine emperor insisted on an unconditional surrender.[27] Much to the surprise of the Byzantines, Maria then entered in negotiations with Ivaylo and offered him her hand and the Bulgarian crown on the condition that he would guarantee the rights of Michael Asen as his sole successor.[30] Contemporary chronicler George Pachymeres accuses Maria of "ignoring the moral duty to her late husband"[31] but in fact her decision was driven by her hatred of her uncle Michael VIII, whom she considered a heretic[a], as well as by her desire to retain power.[30] At first, Ivaylo was reluctant to accept the proposal claiming that Maria was offering what he was about to take by force[30] but eventually conceded "because of the peace and to avoid bloodshed in a civil war".[32] However, Ivaylo made it clear that he was the one giving clemency, not the one receiving it.[33]

In the spring of 1278 Ivaylo entered Tarnovo in triumph, married Maria and was proclaimed emperor.[33][34][35] However, since he was inexperienced in state affairs, Ivaylo failed to consolidate his authority over the nobility in the capital, who were concerned with their own influence, and often quarrelled with Maria.[33][36] He still had to deal with overwhelming challenges — the Byzantines dispatched many troops under the command of Michael Glabas in support of Ivan Asen III and incited the Mongols to attack from the north to open war on two fronts. Yet Ivaylo vigorously prepared his forces to counter the adversaries and managed to gain support among many nobles.[32]

Campaigns against Byzantines and Mongols

[edit]Ivaylo left Tarnovo in the summer of 1278, marched north and defeated the Mongols, pushing them across the Danube river.[37][38] The situation to the south was more dangerous. The Byzantines launched an attack on a wide front along the Balkan Mountains from the Shipka Pass to the Black Sea. They failed to cross the mountains as the defenders held on until the Mongols were defeated and reinforcement could be sent.[38] Despite the huge efforts and numerical superiority, the Byzantines made few gains at very high cost.[34] For instance, the fortress of Ktenia was seized after many assaults, the castles of Kran and Maglizh fell with heavy casualties for the invaders.[38] The Bulgarian commander Stan fell valiantly during the defence of Boruy and many other of Ivaylo's associates distinguished themselves in the war — Momchil, Kuman, Damyan, Kancho.[37][38] All battles led personally by Ivaylo were successful — he fought at Studena and Pirgitsa[38] — and by the autumn of 1278, the Bulgarians gained the upper hand, forcing the Byzantines to abandon the campaign.[37][38] Byzantine morale was very low because Ivaylo gave no quarter. George Pachymeres wrote that "to fall in the hands of Lakhanas [Ivaylo] was equivalent to death".[39]

With the situation to the south under control, Ivaylo had to confront a second Mongol attack to the north. This time the Bulgarians faced the elite forces of Nogai Khan. The Mongols prevailed and Ivaylo was besieged in the important city of Drastar on the southern bank of the Danube, where he withstood a three-month siege.[37][40] While most of the rebel army was engaged in the north, Michael VIII started negotiating with the nobility in Tarnovo and convinced the local dignitaries to recognize the claim of Ivan Asen III.[40] In the beginning of 1279, a Byzantine army under Michael Glabas disembarked near Varna and set off to the capital, supported by a Mongol unit commanded by Kasim beg.[36] The elite of Tarnovo spread rumours that Ivaylo had perished fighting the Mongols and opened the gates to the Byzantines and their protégé. Ivan Asen III was proclaimed emperor and Maria, who at the time bore Ivaylo's child, was exiled to Constantinople.[34][35][37] To consolidate the support of the nobility, the new monarch married his sister Kira Maria to George Terter, one of Bulgaria's most powerful and influential feudal lords, whose estates were centred at Cherven.[41] Kasim beg, who had been awarded the high court title protostrator, felt that the rise of George Terter was at his expense, deserted Ivan Asen III and joined the cause of Ivaylo.[42]

Meanwhile, fighting between the rebels and the Byzantines continued. Although the Bulgarian forces were cut in two after the Byzantine landing at Varna, heavy clashes erupted in the eastern Balkan Mountains with new vigour, especially around the Kotel Pass and the Varbitsa Pass.[40] The Bulgarian positions there were surrounded both from the north and the south. The Byzantines had to besiege and take the fortresses one by one which cost time and casualties. Many strongholds remained unconquered and permanently engaged large Byzantine forces.[42]

In spring 1279, Ivaylo managed to break through the Mongol blockade at Drastar and besieged Tarnovo. This advance took Ivan Asen III and his supporters by surprise.[42][43] Michael VIII took measures to protect his protégé and in the summer of 1279 sent a 10,000-strong army under the command of the protovestiarios Murin. Ivaylo did not linger in Tarnovo and engaged the invading host on 17 June 1279 in the Kotel Pass. Despite being outnumbered, in the ensuing battle near the fortress of Devina the Bulgarians achieved a complete victory. Part of the Byzantines perished in the battle along with their commander, the rest were captured and killed by orders of Ivaylo.[34][44][45] A month later, the Byzantines sent another army of 5,000 troops led by the protovestiarios Aprin. Ivaylo engaged them in the eastern Balkan Mountains on 15 August 1279 and after a long combat defeated the Byzantines, personally killing Aprin in the process.[44][45] Ivaylo was said to had "fought with fury, achieving many feats"[46] in both battles.

End of the rebellion and demise of Ivaylo

[edit]

With the Byzantines defeated, the authority of Ivan Asen III was shaken. He and Irene secretly fled Tarnovo, taking the Byzantine imperial insignia, which were kept in the treasury since the Bulgarian victory in the battle of Tryavna in 1190.[47][b] Michael VIII was infuriated with the couple's cowardliness and refused to grant them an audience for days.[45] In Tarnovo, the nobility refused to open the gates to Ivaylo and instead elected George Terter emperor, which had a devastating effect on the rebels.[44] Despite the military successes, neither was the Mongol threat dealt with, nor was Ivaylo able to secure the support of the Bulgarian nobility and unify the country against the overwhelming forces of the Mongols and the Byzantines. As a result, Ivaylo's followers, disillusioned with the endless wars without prospects for peace, began to abandon his cause. With diminished support, in 1280 Ivaylo crossed the Danube with a few loyal associates, including Kasim beg, to seek aid from Nogai Khan.[34][45][48]

Initially, Ivaylo was received well by Nogai Khan. When news of his whereabouts reached Constantinople, Michael VIII sent Ivan Asen III with rich gifts to the Mongol court to ask assistance.[45][48][49] Nogai Khan expressed interest in the issue and for several months kept promising help to both pretenders. Eventually the Byzantine influence prevailed because the Mongol leader was married to the illegitimate daughter of Michael VIII, Euphrosyne Palaiologina.[49] During a feast, in which Ivaylo and Ivan Asen III seated on both sides of Nogai Khan, he pointed at Ivaylo with the words "He is an enemy of my father, the Emperor [Michael VIII], and does not deserve to live"[50] and ordered his execution. Ivaylo, along with Kasim beg, were duly murdered on the spot.[34][45][49] Ivan Asen III was fortunate to avoid that fate due to the advocacy of Euphrosyne and eventually returned to his estates in Asia Minor, where he died in 1303.[48][51]

Aftermath

[edit]...the peasants left their lands and agrarian labour and under their own will became soldiers [...], determined to line up under the banner of Lakhanas, confident that they will win with him.[52]

— George Pachymeres on Pseudo-Ivaylo.

Ivaylo's legacy enjoyed huge popularity beyond the borders of Bulgaria years after his death. At least two "Pseudo-Ivaylos" appeared in the Byzantine Empire.[53] In 1284 a Bulgarian who claimed to had been Ivaylo, arrived in Constantinople and offered his services to Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos to fight against the Turks.[54] Andronikos II asked the ex-empress Maria to verify if the man was her husband and she exposed him as an imposter. Pseudo-Ivaylo was detained but the populace demanded his release since the Turks "feared the barbarian [Ivaylo]".[52] The Byzantine emperor calculated that there was nothing to lose and allowed him to march against the Turks. "Ivaylo" gathered a huge army of peasants, much to the concern of the Byzantine nobility who feared a revolt or coup. The emperor then summoned Pseudo-Ivaylo under some pretext and had him imprisoned.[54] A few years later, another Bulgarian (whose real name was Ivan) appeared in the Byzantine Empire claiming he was Ivaylo. He was given an army to combat the Turks but after a few victories he was captured and killed.[54]

In Bulgaria, the two decades after the end of the rebellion were the lowest point of the Second Empire.[54] The reigns of George Terter I (r. 1280–1292) and his successor Smilets (r. 1292–1298) were characterised by constant Mongol interference in the state's domestic affairs and progressive disintegration of Imperial authority in favour of the feudal magnates.[55] Bulgaria had lost almost all lands to the south of the Balkan mountains to the Byzantines and was in no position to regain these regions.[56] The fortunes of the country changed for the better under George Terter I's son, Theordore Svetoslav (r. 1300–1321), when Bulgaria acquired Bessarabia from the Mongols and reconquered Northern Thrace from the Byzantines, bringing stability and prosperity.[57]

Legacy

[edit]The rebellion failed because the rebels had to fight against overwhelming odds — not only the Byzantines and the Mongols, but also much of the Bulgarian nobility.[34][45] Although ultimately unsuccessful, the uprising of Ivaylo had achieved a recognition of its leader as emperor, an aim in which all other popular revolts in medieval Europe failed. In Socialist Bulgaria, the rebellion was portrayed as a social movement against the iniquity of the feudal system and the foreign invaders.[29] In modern Bulgaria, Ivaylo is still revered as a fighter for freedom and social justice.[53] However, there is no evidence that Ivaylo and his followers ever intended to conduct social reforms.[29] The fact that the rebellion was supported by some nobles and that Ivaylo married the hated Empress Maria also indicates that the main factor was the incompetent rule of Emperor Constantine Tikh.[29] Bulgarian historians praise the heroism of the rebels and evaluate the uprising as a bright patriotic achievement of the Bulgarian people because Ivaylo was able to gather wide support from all social classes of Bulgaria to defend the then-troubled country against the external enemies.[34][49] Ivaylo is remembered as a heroic ruler and a tragic figure who represented the ideal of the "Good Tsar".[58]

The rebellion of Ivaylo is among the most popular and recognizable Bulgarian historical events with numerous pieces of art dedicated to it. The 1959 opera "Ivaylo" by the composer Marin Goleminov, based on the overture of the same name by Dobri Hristov, was inspired by the "revolutionary pathos and tragedy of the epoch".[59] Dedicated to the uprising are also the 1964 colour feature film "Ivaylo" by the director Nikola Valchev, based on the novel "The Smouldering Ember" by Evgeni Konstantinov,[60] and the 1921 drama "The Throne" by prominent Bulgarian poet and writer Ivan Vazov.[61] The town of Ivaylovgrad in modern southern Bulgaria and the village of Ivaylo near the city of Pazardzhik are named after the rebel leader. There are statues in several cities dedicated to him, as well as a monument commemorating the victory over the Byzantines in the battle of Devina, situated at 5 km to the south-east of the town of Kotel. That memorial, named "The Stone Guard", was listed in the top ten emblematic monuments in the history of Bulgaria.[62][63]

Timeline

[edit]- summer of 1277 — The Mongols are defeated

- autumn of 1277 — The Mongols are driven out of Bulgaria

- end of 1277 — The army of Constantine Tikh is defeated; the emperor is killed by Ivaylo

- spring of 1278 — Ivaylo enters the capital Tarnovo; marries Constantine Tikh's wife Maria; crowned Emperor of Bulgaria

- summer and autumn of 1278 — Warfare against Byzantines and Mongols; victory over the Byzantines; defeat against the Mongols; Ivaylo is besieged in Drastar

- beginning of 1279 — The nobility in Tarnovo opens the gates to the Byzantine-supported pretender Ivan Asen III

- spring of 1279 — Ivaylo breaks the Mongol blockade at Drastar; besieges Tarnovo; Ivan Asen III flees to Constantinople

- 17 June 1279 — A 10,000-strong Byzantine army is defeated in the battle of Devina

- 15 August 1279 — A 5,000-strong Byzantine army is defeated in the eastern Balkan Mountains

- beginning of 1280 — George Terter I is elected emperor by the nobility

- 1280 — Ivaylo flees to Nogai Khan and is eventually murdered

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]Notes

[edit]^ a: The Bulgarian Orthodox Church vigorously opposed the attempts to reunite the Orthodox and the Catholic Churches sponsored by Michael VIII and the Patriarchate of Constantinople. The Bulgarian patriarch Ignatius and empress Maria criticised them for their apparent willingness to make concessions at the Second Council of Lyon in 1272–1274.[64]

^ b: In the battle of Tryavna in 1190 the Bulgarians captured the Byzantine imperial treasure, including the golden helmet of the Byzantine Emperors, the crown and the Imperial Cross, which was considered the most valuable possession of the Byzantine rulers — a reliquary of solid gold containing a piece of the True Cross. These trophies became part of the Bulgarian treasury and were carried around Tarnovo during official occasions until 1279, when Ivan Asen III took them during his flight from the capital.[65]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 192–193

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 154–155

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 155

- ^ Bakalov et al 2003, p. 357

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, pp. 508–509

- ^ Fine 1987, pp. 171–172

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 174

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 513

- ^ a b c d e f g Fine 1987, p. 195

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 218

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, pp. 513–514

- ^ Angelov et al 1981, p. 215

- ^ a b c Angelov et al 1981, p. 277

- ^ Bakalov et al 2003, p. 359

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 221

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 220

- ^ Bakalov et al 2003, pp. 359–360

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 515

- ^ "De Michaele et Andronico Paleologis by George Pachymeres" in GIBI, vol. X, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 171

- ^ a b Bakalov et al 2003, p. 360

- ^ "De Michaele et Andronico Paleologis by George Pachymeres" in GIBI, vol. X, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 172

- ^ Angelov et al 1981, p. 279

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 222

- ^ Angelov et al 1981, pp. 280–281

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 223

- ^ Angelov et al 1981, p. 281

- ^ a b c d Angelov et al 1981, p. 282

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 230–231

- ^ a b c d e Fine 1987, p. 196

- ^ a b c Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 224

- ^ "De Michaele et Andronico Paleologis by George Pachymeres" in GIBI, vol. X, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 177

- ^ a b "De Michaele et Andronico Paleologis by George Pachymeres" in GIBI, vol. X, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 178

- ^ a b c Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 225

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bakalov et al 2003, p. 361

- ^ a b Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 518

- ^ a b Fine 1987, p. 197

- ^ a b c d e Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 226

- ^ a b c d e f Angelov et al 1981, p. 285

- ^ "De Michaele et Andronico Paleologis by George Pachymeres" in GIBI, vol. X, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 179

- ^ a b c Angelov et al 1981, p. 286

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 235

- ^ a b c Angelov et al 1981, p. 287

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 226–227

- ^ a b c Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 227

- ^ a b c d e f g Angelov et al 1981, p. 288

- ^ "De Michaele et Andronico Paleologis by George Pachymeres" in GIBI, vol. X, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 181

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 233

- ^ a b c Fine 1987, p. 198

- ^ a b c d Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 228

- ^ "De Michaele et Andronico Paleologis by George Pachymeres" in GIBI, vol. X, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 182

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 233–234

- ^ a b "De Michaele et Andronico Paleologis by George Pachymeres" in GIBI, vol. X, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, p. 187

- ^ a b Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 229

- ^ a b c d Angelov et al 1981, p. 290

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 238, 242

- ^ Fine 1987, p. 199

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 251

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 222, 229

- ^ Sagaev, Lyubomir (1983). "Ivaylo". Book for the Opera (in Bulgarian).

- ^ "Ivaylo (1964)". IMDb. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ "Bulgarian Literature from 1879 to 1988". Literary Club (in Bulgarian). Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ "Ten Emblematic Monuments on Bulgarian History". Economic.bg (in Bulgarian). 12 January 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ "Monument of Ivaylo - Kotel" (in Bulgarian). Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 514

- ^ Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 155

Sources

[edit]References

[edit]- Андреев (Andreev), Йордан (Jordan); Лалков (Lalkov), Милчо (Milcho) (1996). Българските ханове и царе (The Bulgarian Khans and Tsars) (in Bulgarian). Велико Търново (Veliko Tarnovo): Абагар (Abagar). ISBN 954-427-216-X.

- Ангелов (Angelov), Димитър (Dimitar); Божилов (Bozhilov), Иван (Ivan); Ваклинов (Vaklinov), Станчо (Stancho); Гюзелев (Gyuzelev), Васил (Vasil); Куев (Kuev), Кую (kuyu); Петров (Petrov), Петър (Petar); Примов (Primov), Борислав (Borislav); Тъпкова (Tapkova), Василка (Vasilka); Цанокова (Tsankova), Геновева (Genoveva) (1981). История на България. Том II. Първа българска държава [History of Bulgaria. Volume II. First Bulgarian State] (in Bulgarian). и колектив. София (Sofia): Издателство на БАН (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Press).

- Бакалов (Bakalov), Георги (Georgi); Ангелов (Angelov), Петър (Petar); Павлов (Pavlov), Пламен (Plamen); Коев (Koev), Тотю (Totyu); Александров (Aleksandrov), Емил (Emil) (2003). История на българите от древността до края на XVI век (History of the Bulgarians from Antiquity to the end of the XVI century) (in Bulgarian). и колектив. София (Sofia): Знание (Znanie). ISBN 954-621-186-9.

- Божилов (Bozhilov), Иван (Ivan); Гюзелев (Gyuzelev), Васил (Vasil) (1999). История на средновековна България VII–XIV век (History of Medieval Bulgaria VII–XIV centuries) (in Bulgarian). София (Sofia): Анубис (Anubis). ISBN 954-426-204-0.

- Fine, J. (1987). The Late Medieval Balkans, A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10079-3.

- Kazhdan, A. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Колектив (Collective) (1980). Гръцки извори за българската история (ЛИБИ), том III (Greek Sources for Bulgarian History (GIBI), volume X) (in Bulgarian and Greek). София (Sofia): Издателство на БАН (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Press).

External links

[edit]- "Uprising of Ivaylo 1277–1280" (in Bulgarian). Electronic History of Bulgaria hosted on the Bulgarian Knowledge Portal. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- 13th-century rebellions

- Byzantine–Bulgarian Wars

- Bulgarian rebellions

- Rebellions against empires

- 13th century in Bulgaria

- 13th-century conflicts

- Wars involving the Golden Horde

- Conflicts in 1277

- Conflicts in 1278

- Conflicts in 1279

- Conflicts in 1280

- 1277 in Europe

- 1278 in Europe

- 1279 in Europe

- 1280 in Europe

- Popular revolt in late-medieval Europe

- Peasant revolts

- Medieval rebellions in Europe

- Michael VIII Palaiologos

- 1270s in the Mongol Empire