Unequal treaties

| Unequal treaties | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 不平等條約 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 不平等条约 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||

| Hangul | 불평등 조약 | ||||||||||||

| Hanja | 不平等條約 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||

| Kanji | 不平等条約 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

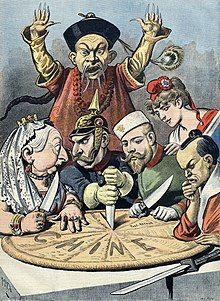

The unequal treaties were a series of agreements made between Asian countries—most notably Qing China, Tokugawa Japan and Joseon Korea—and Western countries—most notably the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, the United States and Russia—during the 19th and early 20th centuries.[1] They were often signed following a military defeat suffered by the Asian party, or amid military threats made by the Western party. The terms specified obligations to be borne almost exclusively by the Asian party and included provisions such as the cession of territory, payment of reparations, opening of treaty ports, relinquishment of the right to control tariffs and imports, and granting of extraterritoriality to foreign citizens.[2]

With the rise of Chinese nationalism and anti-imperialism in the 1920s, both the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party used the concept to characterize the Chinese experience of losing sovereignty between roughly 1840 to 1950. The term "unequal treaty" became associated with the concept of China's "century of humiliation", especially the concessions to foreign powers and the loss of tariff autonomy through treaty ports, and continues to serve as a major impetus for the foreign policy of China today.

Japan and Korea also use the term to refer to several treaties that resulted in a reduction of their national sovereignty. Japan and China signed treaties with Korea such as the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876 and China–Korea Treaty of 1882, with each granting privileges to the former parties concerning Korea. Japan after the Meiji Restoration also began enforcing unequal treaties against China after its victory in the First Sino-Japanese War for influence over Korea as well as China's coastal ports and territories.

China

[edit]

In China, the term "unequal treaties" first came into use in the early 1920s to describe the historical treaties, still imposed on the then-Republic of China, that were signed through the period of time which the American sinologist John K. Fairbank characterized as the "treaty century" which began in the 1840s.[3] The term was popularized by Sun Yat-sen.[4]: 53

In assessing the term's usage in rhetorical discourse since the early 20th century, American historian Dong Wang notes that "while the phrase has long been widely used, it nevertheless lacks a clear and unambiguous meaning" and that there is "no agreement about the actual number of treaties signed between China and foreign countries that should be counted as unequal."[3] However, within the scope of Chinese historiographical scholarship, the phrase has typically been defined to refer to the many cases in which China was effectively forced to pay large amounts of financial reparations, open up ports for trade, cede or lease territories (such as Outer Manchuria and Outer Northwest China (including Zhetysu) to the Russian Empire, Hong Kong and Weihaiwei to the United Kingdom, Guangzhouwan to France, Kwantung Leased Territory and Taiwan to the Empire of Japan, the Jiaozhou Bay concession to the German Empire and concession territory in Tientsin, Shamian, Hankou, Shanghai etc.), and make various other concessions of sovereignty to foreign spheres of influence, following military threats.[5]

The Chinese-American sinologist Immanuel Hsu states that the Chinese viewed the treaties they signed with Western powers and Russia as unequal "because they were not negotiated by nations treating each other as equals but were imposed on China after a war, and because they encroached upon China's sovereign rights ... which reduced her to semicolonial status".[6]

The earliest treaty later referred to as "unequal" was the 1841 Convention of Chuenpi negotiations during the First Opium War. The first treaty between the Qing dynasty and the United Kingdom termed "unequal" was the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842.[5]

Following Qing China's defeat, treaties with Britain opened up five ports to foreign trade, while also allowing foreign missionaries, at least in theory, to reside within China. Foreign residents in the port cities were afforded trials by their own consular authorities rather than the Chinese legal system, a concept termed extraterritoriality.[5] Under the treaties, the UK and the US established the British Supreme Court for China and Japan and United States Court for China in Shanghai.

The unequal treaties gave European powers jurisdiction over missions in China and some authority over Chinese Christians.[7]: 182

Chinese post-World War I resentment

[edit]After World War I, patriotic consciousness in China focused on the treaties, which now became widely known as "unequal treaties." The Nationalist Party and the Chinese Communist Party competed to convince the public that their approach would be more effective.[5] Germany was forced to terminate its rights, the Soviet Union surrendered them, and the United States organized the Washington Conference to negotiate them.[8]

After Chiang Kai-shek declared a new national government in 1927, the Western powers quickly offered diplomatic recognition, arousing anxiety in Japan.[8] The new government declared to the Great Powers that China had been exploited for decades under unequal treaties, and that the time for such treaties was over, demanding they renegotiate all of them on equal terms.[9]

Towards the end of the unequal treaties

[edit]After the Boxer Rebellion and the signing of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902, Germany began to reassess its policy approach towards China. In 1907 Germany suggested a trilateral German-Chinese-American agreement that never materialised. Thus China entered the new era of ending unequal treaties on March 14, 1917, when it broke off diplomatic relations with Germany, thereby terminating the concessions it had given that country, with China declaring war on Germany on August 17, 1917.[10]

As World War I commenced, these acts voided the unequal treaty of 1861, resulting in the reinstatement of Chinese control on the concessions of Tianjin and Hankou to China. In 1919, the post-war peace negotiations failed to return the territories in Shandong, previously under German colonial control, back to the Republic of China. After it was determined that the Japanese forces occupying those territories since 1914 would be allowed to retain them under the Treaty of Versailles, the Chinese delegate Wellington Koo refused to sign the peace agreement, with China being the only conference member to boycott the signing ceremony. Widely perceived in China as a betrayal of the country's wartime contributions by the other conference members, the domestic backlash following the failure to restore Shandong would cause the collapse of the cabinet of the Duan Qirui government and lead to the May 4th movement.[11][12]

On May 20, 1921, China secured with the German-Chinese peace treaty (Deutsch-chinesischer Vertrag zur Wiederherstellung des Friedenszustandes) a diplomatic accord which was considered the first equal treaty between China and a European nation.[10]

During the Nanjing period, the Republic of China unsuccessfully sought to negotiate an end to the unequal treaties.[13]: 69-70

Many treaties China considered unequal were repealed during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, China became an ally with the United Kingdom and the United States, which then signed treaties with China to end British and American extraterritoriality in January 1943.[14] Significant examples outlasted World War II: treaties regarding Hong Kong remained in place until Hong Kong's 1997 handover, though in 1969, to improve Sino-Soviet relations in the wake of military skirmishes along their border, the People's Republic of China was forced to reconfirm the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and 1860 Treaty of Peking.[citation needed]

Japan

[edit]Prior to the Meiji Restoration, Japan was also subject to numerous unequal treaties. When the US expeditionary fleet led by Matthew Perry reached Japan in 1854 to force open the island nation for American trade, the country was compelled to sign the Convention of Kanagawa under the threat of violence by the American warships.[15] This event abruptly terminated Japan's 220 years of seclusion under the Sakoku policy of 1633 under unilateral foreign pressure and consequentially, the convention has been seen in a similar light as an unequal treaty.[16]

Another significant incident was the Tokugawa Shogunate's capitulation to the Harris Treaty of 1858, negotiated by the eponymous U.S. envoy Townsend Harris, which, among other concessions, established a system of extraterritoriality for foreign residents. This agreement would then serve as a model for similar treaties to be further signed by Japan with other foreign Western powers in the weeks to follow, such as the Ansei Treaties.[17]

Unequal treaties with the United States and Europe prevented Japan from unilaterally setting tariff rates on imported goods.[18]: 8 As a result, it was hampered in developing domestic industries that could compete with imported goods.[18]: 8

The enforcement of these unequal treaties were a tremendous national shock for Japan's leadership as they both curtailed Japanese sovereignty for the first time in its history and also revealed the nation's growing weakness relative to the West through the latter's successful imposition of such agreements upon the island nation. An objective towards the recovery of national status and strength would become an overarching priority for Japan, with the treaty's domestic consequences being the end of the Bakufu, the 700 years of shogunate rule over Japan, and the establishment of a new imperial government.[19]

The unequal treaties ended at various times for the countries involved and Japan's victories in the 1894–95 First Sino-Japanese War convinced many in the West that unequal treaties could no longer be enforced on Japan as it was a great power in its own right. This view gained more recognition following the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, whereby Japan most notably defeated Russia in a massive humiliation for the latter.[20]

Korea

[edit]Korea's first unequal treaty was not with the West, but instead with Japan. The Ganghwa Island incident in 1875 saw Japan send the warship Un'yō led by Captain Inoue Yoshika with the implied threat of military action to coerce the Korean kingdom of Joseon through the show of force. After an armed clash ensued around Ganghwa Island where the Japanese force was sent, which resulted in its victory, the incident subsequently forced Korea to open its doors to Japan by signing the Treaty of Ganghwa Island, also known as the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876.[21]

During this period Korea also signed treaties with Qing China and the West powers (such as the United Kingdom and the United States). In the case of Qing China, it signed the China–Korea Treaty of 1882 with Korea stipulating that Korea was a dependency of China and granted the Chinese extraterritoriality and other privileges,[22] and in subsequent treaties China also obtained concessions in Korea, such as the Chinese concession of Incheon.[23][24] However, Qing China lost its influence over Korea following the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895.[25]

As Japanese dominance over the Korean peninsula grew in the following decades, with respect to the unequal treaties imposed upon the kingdom by the West powers, Korea's diplomatic concessions with those states became largely null and void in 1910, when it was annexed by Japan.[26]

Selected list of unequal treaties

[edit]Imposed on China

[edit]Imposed on Japan

[edit]Imposed on Korea

[edit]Modern rhetorical usage

[edit]In 2018, Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamad criticized the terms of infrastructure projects under the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative in Malaysia,[59][60] stating that "China knows very well that it had to deal with unequal treaties in the past imposed upon China by Western powers. So China should be sympathetic toward us. They know we cannot afford this."[61]

See also

[edit]- Century of humiliation

- China Centenary Missionary Conference

- Client state

- Foreign concessions in China

- List of Chinese treaty ports

- List of treaties of China before the People's Republic

- Most favoured nation

- Normanton incident

- Puppet state

- Sick man of Asia

- Western imperialism in Asia

References

[edit]- ^ "Unequal Treaties with China". Encyclopédie d’histoire numérique de l’Europe. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ Fravel, M. Taylor (October 1, 2005). "Regime Insecurity and International Cooperation: Explaining China's Compromises in Territorial Disputes". International Security. 30 (2): 46–83. doi:10.1162/016228805775124534. ISSN 0162-2889. S2CID 56347789.

- ^ a b Wang, Dong. (2005). China's Unequal Treaties: Narrating National History. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780739112083.

- ^ Crean, Jeffrey (2024). The Fear of Chinese Power: an International History. New Approaches to International History series. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-350-23394-2.

- ^ a b c d Dong Wang, China's Unequal Treaties: Narrating National History (Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2005).

- ^ Hsu, Immanuel C. Y. (1970). The Rise of Modern China. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 239. ISBN 0195012402.

- ^ Moody, Peter (2024). "The Vatican and Taiwan: An Anomalous Diplomatic Relationship". In Zhao, Suisheng (ed.). The Taiwan Question in Xi Jinping's Era: Beijing's Evolving Taiwan Policy and Taiwan's Internal and External Dynamics. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781032861661.

- ^ a b Akira Iriye, After Imperialism: The Search for a New Order in the Far East, 1921–1931 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965; Reprinted: Chicago: Imprint Publications, 1990), passim.

- ^ "CHINA: Nationalist Notes". TIME. June 25, 1928. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ a b Andreas Steen: Deutsch-chinesische Beziehungen 1911-1927: Vom Kolonialismus zur „Gleichberechtigung“. Eine Quellensammlung. Berlin, Akademie-Verlag 2006, S. 221.

- ^ Dreyer, June Teufel (2015). China's Political System. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-317-34964-8

- ^ "May Fourth Movement". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Laikwan, Pang (2024). One and All: The Logic of Chinese Sovereignty. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9781503638815.

- ^ "FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES: DIPLOMATIC PAPERS, 1943, CHINA". Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ Hall, John Whitney; Hall, John Whitney (1991). Japan: from prehistory to modern times. Michigan classics in Japanese studies. Ann Arbor, Mich: Center for Japanese Studies, the Univ. of Michigan. ISBN 978-0-939512-54-6.

- ^ Miyauchi, D. Y. (May 1970). "Yokoi Shōnan's Response to the Foreign Intervention in Late Tokugawa Japan, 1853–1862". Modern Asian Studies. 4 (3): 269–290. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00011938. ISSN 0026-749X. S2CID 145055046.

- ^ Michael R. Auslin (2006). Negotiating with Imperialism: The Unequal Treaties and the Culture of Japanese Diplomacy. Harvard University Press. pp. 17, 44. ISBN 9780674020313.

- ^ a b Hirata, Koji (2024). Making Mao's Steelworks: Industrial Manchuria and the Transnational Origins of Chinese Socialism. Cambridge Studies in the History of the People's Republic of China series. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-38227-4.

- ^ Totman, Conrad (1966). "Political Succession in The Tokugawa Bakufu: Abe Masahiro's Rise to Power, 1843–1845". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 26: 102–124. doi:10.2307/2718461. JSTOR 2718461.

- ^ Oye, David Schimmelpenninck van der (January 1, 2005). "The Immediate Origins of the War". The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective: 23–44. doi:10.1163/9789047407041_008. ISBN 978-90-474-0704-1.

- ^ Preston, Peter Wallace. [1998] (1998). Blackwell Publishing. Pacific Asia in the Global System: An Introduction. ISBN 0-631-20238-2

- ^ Duus, Peter (1998). The Abacus and the Sword: The Japanese Penetration of Korea. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-52092-090-2.

- ^ "Guide to Incheon's Chinatown". March 3, 2022. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Fuchs, Eckhardt (2017). A New Modern History of East Asia. V&R unipress GmbH. p. 97. ISBN 978-3-7370-0708-5.

- ^ Paine, S. C. M. (November 18, 2002). "The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy". Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511550188. ISBN 978-0-521-81714-1.

- ^ I. H. Nish, "Japan Reverses the Unequal Treaties: The Anglo-Japanese Commercial Treaty of 1894," Journal of Oriental Studies (1975) 13#2 pp 137-146.

- ^ Ingemar Ottosson (2019). Möten i monsunen.

- ^ Auslin, Michael R. (2004) Negotiating with Imperialism: The Unequal Treaties and the Culture of Japanese Diplomacy, p. 17., p. 17, at Google Books

- ^ Auslin, p. 30., p. 30, at Google Books

- ^ Auslin, pp. 1, 7., p. 1, at Google Books

- ^ Auslin, p. 71., p. 71, at Google Books

- ^ Auslin, Michael R. (2004) Negotiating with Imperialism: The Unequal Treaties and the Culture of Japanese Diplomacy, p. 154., p. 154, at Google Books

- ^ Howland, Douglas (2016). International Law and Japanese Sovereignty: The Emerging Global Order in the 19th Century. Springer. ISBN 9781137567772.

- ^ Dreyer, June Teufel (2016). Middle Kingdom and Empire of the Rising Sun: Sino-Japanese Relations, Past and Present. Oxford University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-19-537566-4.

- ^ Korean Mission to the Conference on the Limitation of Armament, Washington, D.C., 1921–1922. (1922). Korea's Appeal to the Conference on Limitation of Armament, p. 33., p. 33, at Google Books; excerpt, "Treaty Between Japan and Korea, dated February 26, 1876."

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 29., p. 29, at Google Books; excerpt, "Treaty and Diplomatic Relations Between the United States and Korea. Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation dated May 22, 1882."

- ^ Moon, Myungki. "Korea-China Treaty System in the 1880s and the Opening of Seoul: Review of the Joseon-Qing Communication and Commerce Rules," Archived October 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Journal of Northeast Asian History, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Dec 2008), pp. 85–120.

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 32., p. 32, at Google Books; excerpt, "Treaty and Diplomatic Relations Between Germany and Korea. Treaty of Amity and Commerce dated November 23, 1883."

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 32., p. 32, at Google Books; excerpt, "Treaty and Diplomatic Relations Between Great Britain and Korea ... dated November 26, 1883."

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 32., p. 32, at Google Books; excerpt, "Treaty and Diplomatic Relations Between Korea and Russia. Treaty of Amity and Commerce dated June 25, 1884."

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 32., p. 32, at Google Books; excerpt, "Treaty and Diplomatic Relations Between Korea and Italy. Treaty of Friendship and Commerce dated June 26, 1884."

- ^ Yi, Kwang-gyu and Joseph P. Linskey. (2003). Korean Traditional Culture, p. 63., p. 63, at Google Books; excerpt, "The so-called Hanseong Treaty was concluded between Korea and Japan. Korea paid compensation for Japanese losses. Japan and China worked out the Tien-Tsin Treaty, which ensured that both Japanese and Chinese troops withdraw from Korea."

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 32., p. 32, at Google Books; excerpt, "Treaty and Diplomatic Relations Between Korea and France. Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation dated June 4, 1886."

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 32., p. 32, at Google Books; excerpt, "Treaty and Diplomatic Relations Between Korea and Austria. Treaty of Amity and Commerce dated July 23, 1892."

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 32., p. 32, at Google Books; excerpt, "Treaty and Diplomatic Relations Between Korea and Belgium. Treaty of Amity and Commerce dated March 23, 1901."

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 32., p. 32, at Google Books; excerpt, "Treaty and Diplomatic Relations Between Korea and Denmark. Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation dated July 15, 1902."

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 34., p. 34, at Google Books; excerpt, "Treaty of Alliance Between Japan and Korea, dated February 23, 1904."

- ^ Note that the Korean Mission to the Conference on the Limitation of Armament in Washington, D.C., 1921–1922 identified this as "Treaty of Alliance Between Japan and Korea, dated February 23, 1904"

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 35., p. 35, at Google Books; excerpt, "Alleged Treaty, dated August 22, 1904."

- ^ Note that the Korean diplomats in 1921–1922 identified this as "Alleged Treaty, dated August 22, 1904"

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 35., p. 35, at Google Books; excerpt, "Alleged Treaty, dated April 1, 1905."

- ^ Note that the Korean diplomats in 1921–1922 identified this as "Alleged Treaty, dated April 1, 1905"

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 35., p. 35, at Google Books; excerpt, "Alleged Treaty, dated August 13, 1905."

- ^ Note that the Korean diplomats in 1921–1922 identified this as "Alleged Treaty, dated August 13, 1905"

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 35., p. 35, at Google Books; excerpt, "Alleged Treaty, dated November 17, 1905."

- ^ Note that the Korean diplomats in 1921–1922 identified this as "Alleged Treaty, dated November 17, 1905"

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 35., p. 35, at Google Books; excerpt, "Alleged Treaty, dated July 24, 1907."

- ^ Korean Mission, p. 36., p. 36, at Google Books; excerpt, "Alleged Treaty, dated August 20, 1910."

- ^ Bland, Ben (June 24, 2018). "Malaysian backlash tests China's Belt and Road ambitions". Financial Times. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ "Analysis | New Malaysian government steps back from spending, Chinese projects". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ Beech, Hannah (August 20, 2018). "'We Cannot Afford This': Malaysia Pushes Back Against China's Vision". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Auslin, Michael R. (2004). Negotiating with Imperialism: The Unequal Treaties and the Culture of Japanese Diplomacy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01521-0; OCLC 56493769

- Hsü, Immanuel Chung-yueh (1970). The Rise of Modern China. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 300287988

- Nish, I. H (1975). "Japan Reverses the Unequal Treaties: The Anglo-Japanese Commercial Treaty of 1894". Journal of Oriental Studies. 13 (2): 137–146.

- Perez, Louis G (1999). Japan Comes of Age: Mutsu Munemitsu & the Revision of the Unequal Treaties. p. 244.

- Ringmar, Erik (2013). Liberal Barbarism: The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wang, Dong (2003). "The Discourse of Unequal Treaties in Modern China". Pacific Affairs. 76 (3): 399–425.

- Wang, Dong. (2005). China's Unequal Treaties: Narrating National History. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739112083.

- Fravel, M. Taylor (2008). Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China's Territorial Disputes. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2887-6

- Halleck, Henry Wager. (1861). International law: or, Rules regulating the intercourse of states in peace and war. New York: D. Van Nostrand. OCLC 852699

- Korean Mission to the Conference on the Limitation of Armament, Washington, D.C., 1921–1922. (1922). Korea's Appeal to the Conference on Limitation of Armament. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 12923609

- Fravel, M. Taylor (2005). Regime Insecurity and International Cooperation: Explaining China's Compromises in Territorial Disputes. International Security. 30 (2): 46–83. doi:10.1162/016228805775124534. ISSN 0162-2889.

- 19th century in China

- 19th century in Japan

- 19th century in Korea

- Boxer Rebellion

- History of European colonialism

- Foreign relations of the Qing dynasty

- Free trade imperialism

- History of the foreign relations of Japan

- Lists of treaties

- Unequal treaties

- Foreign relations of the Empire of Japan

- China–Russian Empire relations

- Extraterritorial jurisdiction