Tommie Broadwater

Tommie Broadwater | |

|---|---|

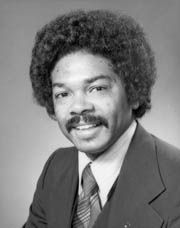

Broadwater in 1982 | |

| Member of the Maryland Senate | |

| In office January 8, 1975 – October 20, 1983 | |

| Preceded by | District established |

| Succeeded by | Decatur "Bucky" Trotter |

| Constituency | 25th district (1975–1982) 24th district (1982–1983) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 9, 1942 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Died | July 11, 2023 (aged 81) Upper Marlboro, Maryland, U.S. |

| Resting place | Fort Lincoln Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Lillian Prince (m. 1958) |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | Fairmont Heights High School |

Tommie Broadwater Jr. (June 9, 1942 – July 11, 2023) was an American politician and businessman who served in the Maryland Senate from 1975 until he was convicted on federal food stamp fraud charges on October 19, 1983. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African-American to serve as a state senator outside of Baltimore in Maryland history.

Early life and education

[edit]Broadwater born in Washington, D.C., on June 9, 1942.[1] He was the second of ten children born to Tommie Broadwater, who worked in construction, and his wife, who was a cook. Broadwater grew up in Prince George's County, Maryland, where he attended segregated schools, including Fairmont Heights High School,[2] and worked at a local Esso gas station. Broadwater later attended Southeastern University before dropping out to become an insurance salesman for Progressive Insurance at the age of 19.[3][4][5]

Career

[edit]Broadwater operated several businesses along Sheriff Road in Landover, Maryland, including Ebony Inn, a barbecue rib joint, and a bail bonding office.[5] In January 1983, he filed for bankruptcy, listing nearly $1 million in debts and $75,000 in back taxes to the Internal Revenue Service,[6] after a supermarket he owned, the Chapel Oaks Farmers Market, failed. Broadwater lost the supermarket, his gas station, and several pieces of real estate following bankruptcy settlement.[7][8] In October 1990, a court evicted Broadwater from his restaurant-theater business, named The Castle, for being $60,000 behind in rent.[9]

Political involvement

[edit]Broadwater became involved in politics to assist African-Americans in accessing better government services and to support his business.[5] Over the course of his political career, he became a "godfather of politics" in Prince George's County.[2][4][10]

Broadwater was elected to the town council of Glenarden, Maryland in 1968, and served on the Prince George's County Democratic Central Committee from 1970 to 1974,[1] where he established links with white politicians who controlled the Maryland Democratic Party, including Steny Hoyer and Peter O'Malley,[11] and helped secure appointments for African American politicians and judges.[3]

Maryland Senate

[edit]Broadwater ran for the Maryland Senate in 1974, defeating state Delegate Arthur A. King in the Democratic primary[12] and running unopposed in the general election.[13]

Broadwater was sworn in on January 8, 1975,[14] becoming the first African-American lawmaker elected to the Maryland Senate outside of Baltimore in Maryland history.[13] and served as a member of the Budget and Taxation Committee and as a vice-chair of the Rules Committee during his entire tenure.[1] He represented the 25th district from 1975 to 1982,[15] and the 24th district from 1982 to 1983.[16]

During his tenure, Broadwater earned a reputation for his flamboyant lifestyle and positioned himself as an advocate for Black issues, such as housing, political representation, and economic growth,[17] which allowed him to build a strong political organization which he used to influence congressional and county elections. Following the 1982 Maryland Senate election, he helped organize an effort by the Legislative Black Caucus of Maryland to oust James Clark Jr. as the President of the Maryland Senate.[6]

In 1980, Broadwater served as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention, pledged to President Jimmy Carter.[18] He again served as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1988.[1]

Conviction

[edit]On March 6, 1983, Broadwater was arrested and charged with conspiring with his daughter and three other men to redeem $70,000 in improperly obtained food stamps in exchange for cash and drugs from an undercover U.S. Secret Service agent.[6][19] During his arrest, federal agents searched his property and found guns and cash, which Broadwater later said was offered back as unrelated to the case, but found no marked food stamps.[20] Broadwater denied participating in any such scheme, saying that he spurned offers from the codefendants to buy the stolen food stamps, and had Senate President Melvin Steinberg and Majority Leader Clarence W. Blount testify as character witnesses.[21] U.S. District Court Judge Norman Park Ramsey sentenced Broadwater to six months in the Federal Correctional Institution, Petersburg federal prison and $38,000 in fines on October 20, 1983, after which he was automatically suspended from the Maryland Senate.[22]

Following his conviction, Broadwater pushed for county committee members to appoint his wife or younger brother to the seat;[23] committee members instead appointed former state Delegate Decatur "Bucky" Trotter to the seat, which Broadwater opposed and whom he criticized as a "puppet of Miller".[24] Upon starting his prison sentence on January 4, 1984, Broadwater declared that he would run for the Maryland Senate in 1986,[25] but he was blocked from running as a result of maneuvering from Senate President Thomas V. Miller Jr.[26] He was released early on May 19, 1984.[27]

Post-prison career

[edit]

Broadwater continued to be active in county politics following his release from prison, hosting political fundraisers[28] and offering advice to dozens of Black politicians in the county including Albert Wynn, Dereck E. Davis, and Wayne K. Curry,[2][29] but would never again hold public office.[30]

In 1990, Broadwater unsuccessfully challenged state Senator Decatur "Bucky" Trotter in District 24, seeking to regain his old Senate seat.[8] He lost the Democratic primary to Trotter by a margin of 346 votes.[9] He unsuccessfully ran for the seat again in 1994,[31] and afterwards backed Nathaniel Exum's successful ouster of Totter in 1998.[5] In 2002, Broadwater ran for the Maryland Senate in District 47 against Gwendolyn T. Britt, a former member of the Prince George's County Democratic Central Committee who had the backing of the county's political establishment.[32][33] Broadwater placed third behind Britt and state Delegate Darren Swain in the Democratic primary on September 10, receiving 22.6 percent of the vote.[34] Following his defeat, he served on the transition team of Prince George's County Executive-elect Jack B. Johnson.[35]

In May 2005, Broadwater was placed on 18 months probation and fined $1,550 for campaign finance violations after failing to file campaign finance reports to the Maryland State Board of Elections.[36]

In July 2020, Prince George's County health officials issued a warning against Broadwater after his neighbors reported that he held a pool party with hundreds of attendees at his mansion amid the COVID-19 pandemic.[37]

Personal life

[edit]Broadwater married his wife, Lillian (née Prince),[1] in 1958 at the age of 16 after she became pregnant.[3] Together, they had four children and lived in Upper Marlboro, Maryland.[2] In 1999, Broadwater's daughter, Tanya, died at the age of 38 from respiratory failure and an infection.[5]

Broadwater was hospitalized to recover from tuberculosis from 1958 to 1959.[3] In October 2003, he underwent a triple bypass surgery.[38]

Broadwater died at his mansion in Upper Marlboro on July 11, 2023, at the age of 81.[2] Following the news of his death, U.S. Representatives Glenn Ivey and Steny Hoyer expressed their condolences.[39] Broadwater was laid in state at the Prince George's County Administration Building[4] before being laid to rest at the Fort Lincoln Cemetery.[40]

Electoral history

[edit]| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Tommie Broadwater Jr. | 5,291 | 74.5 | |

| Independent | Robert A. Spencer | 1,497 | 21.1 | |

| Write-in | 312 | 4.4 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Tommie Broadwater Jr. (incumbent) | 5,542 | 62.1 | |

| Republican | Joseph M. Parker | 3,386 | 37.9 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Tommie Broadwater Jr. (incumbent) | 12,203 | 100.0 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Decatur "Bucky" Trotter (incumbent) | 5,001 | 46.4 | |

| Democratic | Tommie Broadwater Jr. | 4,655 | 43.2 | |

| Democratic | Herbert Jackson | 917 | 8.5 | |

| Democratic | James H. Whitley Jr. | 199 | 1.8 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Decatur "Bucky" Trotter (incumbent) | 6,685 | 60.2 | |

| Democratic | Tommie Broadwater Jr. | 4,413 | 39.8 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Gwendolyn T. Britt | 3,078 | 34.0 | |

| Democratic | Darren Swain | 2,251 | 24.8 | |

| Democratic | Tommie Broadwater | 2,051 | 22.6 | |

| Democratic | Malinda Genevia Miles | 1,069 | 11.8 | |

| Democratic | David Henry Otero | 270 | 3.0 | |

| Democratic | Kay Young | 194 | 2.1 | |

| Democratic | Allieu B. Kallay | 150 | 1.7 | |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Maryland State Senator Tommie Broadwater, Jr". Maryland State Archives. March 16, 2000. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Ford, William J. (July 12, 2023). "Former state Sen. Tommie Broadwater dies at the age of 81". Maryland Matters. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d McQueen, Michel (March 15, 1983). "Still Struggling At 'Making It'". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c Beachum, Lateshia (July 31, 2023). "Prince George's pays respect to Tommie Broadwater Jr". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Schwartzman, Paul (February 11, 2001). "Tommie Broadwater's World". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c Shapiro, Margaret; Sager, Mike (March 7, 1983). "State Senator Is Charged in Stamp Fraud". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Valentine, Paul W. (April 14, 1984). "Broadwater Fends Off Bank Foreclosure". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Meyer, Eugene L. (March 23, 1990). "Broadwater faces new P.G. reality". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Meyer, Eugene L. (October 6, 1990). "Ex-senator's restaurant is evicted". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Malcolm-Lym, Shantelle (July 14, 2023). "Tommie Broadwater, Former Maryland State Senator Passes Away". Maryland Association of Counties. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Perl, Peter (September 29, 1996). "Middle man". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "Primaries: Democratic success varies in rapidly growing D.C. suburbs". The Baltimore Sun. August 18, 1974. Retrieved December 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "D.C. suburbs vote to test Democrats, may split Senate delegation". The Baltimore Sun. October 13, 1974. Retrieved December 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Archives of Maryland, Volume 0716". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "Maryland Senate, Legislative District 25". Maryland State Archives. September 30, 1999. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "Maryland Senate, Legislative District 24". Maryland State Archives. September 30, 1999. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Eastman, Michael (January 24, 1980). "The Black Agenda". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "The Delegates". The Washington Post. August 7, 1980. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Valentine, Paul (March 8, 1983). "Charges Against Broadwater Outlined by U.S. Prosecutors". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Valentine, Paul W. (March 24, 1983). "No Marked Food Stamps Found at Broadwater's". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Valentine, Paul W. (July 28, 1983). "Sen. Broadwater Takes Stand, Denies Charges". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Valentine, Paul W. (October 19, 1983). "Broadwater's Daughter Given Suspended Term". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ McQueen, Michel (September 3, 1983). "Convicted Md. Senator Asks To Have Relative Fill Seat". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Daly, Matthew (August 14, 1986). "Primary '86". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Valentine, Paul W.; McQueen, Michel (January 4, 1984). "Broadwater Enters Prison, Vows to Retake Senate Seat". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Schmidt, Susan (April 11, 1988). "Md.'s Mike Miller coming of age step by step". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Gregg, ra R. (May 19, 1984). "Broadwater Comes Home, Ready to Rebuild". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Raghavan, Sudarsan (June 11, 2005). "Politics, Barbecue and Skin, All Served Up Hot at the Inn". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Sears, Bryan P. (July 21, 2023). "Political Notes: Cardin considers bid to succeed Cardin, Davis recalls Broadwater's advice, regional water task force named". Maryland Matters. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Zorzi, William F. (July 19, 2018). "Tawes: Crabs, Camaraderie, Campaigning. See, Some Things Never Change". Maryland Matters. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Abramowitz, Michael; Tapscott, Richard (June 16, 1994). "Comeback trail for Broadwater". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ LeDuc, Daniel (June 23, 2002). "Political Scandal Redux in Md". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Schwartzman, Paul (September 4, 2002). "Candidate's Past Casts a Long Shadow". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Mosk, Matthew (September 11, 2002). "Schaefer Wins Bitter Race Against Glendening Ally". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Schwartzman, Paul (January 16, 2003). "Johnson Assembles Diverse Interests in Building Transition Team". Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Wiggins, Ovetta (May 17, 2005). "Ex-Senator Fined in Md. Case". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Chason, Rachel; Hedgpeth, Dana (July 30, 2020). "Prince George's to target large parties as D.C.-area coronavirus cases rise". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Harris, Hamil R.; Wiggins, Ovetta (October 9, 2003). "Hospital Executive Played Large Role in Dimensions Report". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Elliott, Richard (July 19, 2023). "Tommie Broadwater 'The Godfather of Prince George's' Dies". The Washington Informer. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "Tommie Broadwater - 2023 - J.B. Jenkins Funeral Home". www.tributearchive.com. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "Archives of Maryland, Volume 0177". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "Archives of Maryland, Volume 0181" (PDF). Maryland State Archives. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "Archives of Maryland, Volume 0181" (PDF). Maryland State Archives. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "1990 Gubernatorial Election". elections.maryland.gov. June 14, 2001. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "1994 Gubernatorial Election". elections.maryland.gov. February 6, 2001. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "2002 Gubernatorial Election". elections.maryland.gov. March 19, 2003. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- 1942 births

- 2023 deaths

- 20th-century African-American politicians

- 20th-century American businesspeople

- 21st-century American businesspeople

- African-American state legislators in Maryland

- American politicians convicted of fraud

- Businesspeople from Maryland

- Democratic Party Maryland state senators

- Maryland politicians convicted of crimes

- People from Upper Marlboro, Maryland

- Politicians from Prince George's County, Maryland

- American political bosses

- Maryland city council members

- African-American city council members in Maryland

- 20th-century members of the Maryland General Assembly

- African-American men in politics