The Hateful Eight

| The Hateful Eight | |

|---|---|

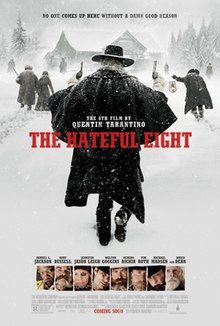

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Quentin Tarantino |

| Written by | Quentin Tarantino |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Richardson |

| Edited by | Fred Raskin |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | The Weinstein Company[2] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | |

| Country | United States[2] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $44–62 million[5][6] |

| Box office | $161.2 million[5] |

The Hateful Eight is a 2015 American Western film written and directed by Quentin Tarantino. It stars Samuel L. Jackson, Kurt Russell, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Walton Goggins, Demián Bichir, Tim Roth, Michael Madsen, and Bruce Dern as eight dubious strangers who seek refuge from a blizzard in a stagecoach stopover some time after the American Civil War.

Tarantino announced the film in November 2013. He conceived it as a novel and sequel to his 2012 film Django Unchained before deciding to make it a standalone film. After the script leaked in January 2014, he decided to abandon the production and publish it as a novel instead. In April 2014, Tarantino directed a live reading of the script at the United Artists Theater in Los Angeles, before reconsidering a new draft and resuming the project. Filming began in January 2015 near Telluride, Colorado. Italian composer Ennio Morricone composed the original score, his first complete Western score in 34 years (and the last before his death in 2020), his first for a high-profile Hollywood production since 2000, and the first and only original score for a Tarantino film.

Distributed by The Weinstein Company in the United States, The Hateful Eight was released on December 25, 2015, in a limited roadshow release on 70 mm film, before expanding wide theatrically five days later. The film was praised for its direction, screenplay, score, cinematography, and performances, though its editing, length, the depiction of race relations and the violent treatment of Leigh's character divided opinions. It grossed over $161 million worldwide. For his work on the score, Morricone won his only Academy Award for Best Original Score after five previous nominations. The film also earned Oscar nominations for Best Supporting Actress (Leigh) and Best Cinematography (Robert Richardson).

In 2019, a re-edited version of the film was released as a four-episode miniseries on Netflix with the subtitle Extended Version. The Hateful Eight is Tarantino's final collaboration with The Weinstein Company following allegations of sexual abuse against Harvey Weinstein in 2017.

Plot

[edit]In 1877, bounty hunter and Union Army veteran cavalry Major Marquis Warren heads to Red Rock, Wyoming Territory, with three bounty corpses. His horse gives out, and, faced with a blizzard, Warren hitches a ride on a stagecoach driven by O.B. Jackson. Aboard is bounty hunter John Ruth "The Hangman", handcuffed to fugitive "Crazy" Daisy Domergue, whom he is taking to Red Rock to be hanged. Warren and Ruth had previously bonded over Warren's personal letter from Abraham Lincoln. Chris Mannix, whose father, Erskine, led a Lost-Causer militia called Mannix's Marauders, claims to be Red Rock's new sheriff and joins them. During the trip, Ruth learns about the Confederate bounty on Warren's head for breaking out of and setting fire to a prisoner-of-war camp.

They seek refuge from the blizzard at Minnie's Haberdashery, tended by Bob, a Mexican who claims to be watching the haberdashery in Minnie's and her husband Sweet Dave's absence. The lodge shelters local hangman Oswaldo Mobray, cowboy Joe Gage, and Confederate general Sanford Smithers, who is planning to erect a cenotaph for his missing son, Chester Charles. Suspicious, Ruth disarms all but Warren. While Mannix recognizes Smithers as a war hero, Warren wants him dead as revenge for ordering the execution of black prisoners of war at Baton Rouge. At dinner, Mannix surmises that the Lincoln letter is fake. Warren responds to Ruth's disappointment by saying his forged letter buys him leeway with whites.

After a small talk, Warren puts one of his guns next to Smithers and claims that he orally raped and murdered Smithers' son, who had tried to claim the bounty. When Smithers reaches for the gun, Warren kills him.

During the confrontation, the coffee is poisoned, which Daisy silently witnessed. Ruth and O.B. drink the coffee; O.B. dies, and Daisy kills the dying Ruth with his own gun. Warren disarms Daisy, leaving her shackled to Ruth's corpse, and holds the others at gunpoint except Mannix, who nearly drank the poisoned coffee himself. Warren deduces, with evidence, that Bob is lying about looking after the haberdashery and kills him. When Warren threatens to kill Daisy, Gage admits that he poisoned the coffee. An unknown man hiding under the floorboards shoots Warren in the groin, and Mobray and Mannix shoot and wound one another.

A flashback shows Bob, Mobray, Gage, and Daisy's brother Jody arriving at the lodge hours earlier. They killed Minnie, Sweet Dave, and all the employees and customers except Smithers, whom they spared to create a believable setting in exchange for his silence. Once they finished hiding the bodies, cleaning the store, and hiding weapons for future use, Jody hid in the cellar as Ruth, Daisy, O.B., Warren and Mannix arrived.

In the present, Warren and Mannix, both seriously wounded, hold Daisy, Gage, and Mobray at gunpoint. When they threaten to kill Daisy, Jody surrenders and is executed by Warren. The surviving gang members claim fifteen hired guns are waiting in Red Rock and offer a deal: if Mannix kills Warren, they will spare him and allow him to collect the bounty on the dying Mobray and the deceased Bob (whose real names are revealed as "English" Pete Hicox and Marco "the Mexican", respectively). Warren kills Hicox when he tries to persuade Mannix. Warren and Mannix then kill Gage (whose real name is "Grouch" Douglass) when he grabs a pistol hidden under a table.

Mannix hears Daisy's proposal but deduces she is lying. When Mannix faints from blood loss, Daisy hacks off Ruth's arm and goes for a gun, but Mannix reawakens and wounds her. Mannix and Warren hang Daisy from the rafters in honor of Ruth, who always brought his bounty to the gallows (which earned him the nickname "The Hangman"). As they lie dying, Mannix reads aloud Warren's fake Lincoln letter, complimenting its detail.

Cast

[edit]- Samuel L. Jackson as Major Marquis Warren, "The Bounty Hunter"

- Kurt Russell as John "The Hangman" Ruth

- Jennifer Jason Leigh as "Crazy" Daisy Domergue, "The Prisoner"

- Walton Goggins as Chris Mannix, "The Sheriff"

- Demián Bichir as Señor Bob / Marco, "The Mexican"

- Tim Roth as Oswaldo Mobray / Pete "English Pete" Hicox, "The Little Man"

- Michael Madsen as Joe Gage / "Grouch" Douglass, "The Cow Puncher"

- Bruce Dern as General Sanford "Sandy" Smithers, "The Confederate"

- James Parks as O.B. Jackson

- Channing Tatum as Jody Domergue

- Dana Gourrier as Minnie Mink

- Zoë Bell as Six-Horse Judy

- Gene Jones as Sweet Dave

- Lee Horsley as Ed

- Keith Jefferson as Charly

- Belinda Owino as Gemma

- Craig Stark as Chester Charles Smithers

Production

[edit]In November 2013, writer-director Quentin Tarantino said he was working on another Western. He initially attempted the story as a novel, a sequel to his film Django Unchained (2012),[7] titled Django in White Hell but realized that the Django character did not fit the story.[8] On January 11, 2014, the title was announced as The Hateful Eight.[9]

The film was inspired by the 1960s Western TV series Bonanza, The Virginian, and The High Chaparral. Tarantino said:

Twice per season, those shows would have an episode where a bunch of outlaws would take the lead characters hostage. They would come to the Ponderosa and hold everybody hostage, or go to Judge Garth's place – Lee J. Cobb played him – in The Virginian and take hostages. There would be a guest star like David Carradine, Darren McGavin, Claude Akins, Robert Culp, Charles Bronson, or James Coburn. I don't like that storyline in a modern context, but I love it in a Western, where you would pass halfway through the show to find out if they were good or bad guys, and they all had a past that was revealed. I thought, 'What if I did a movie starring nothing but those characters? No heroes, no Michael Landons. Just a bunch of nefarious guys in a room, all telling backstories that may or may not be true. Trap those guys together in a room with a blizzard outside, give them guns, and see what happens.[10]

Production was planned for late 2014 in the winter, but after the script leaked online in January 2014, Tarantino considered publishing it as a novel instead. He said he had given the script to a few trusted colleagues, including Reginald Hudlin, Michael Madsen, Bruce Dern, and Tim Roth.[11] This version of the script featured a different ending in which Warren and Mannix attempt to kill Gage in revenge by forcing him to drink the poisoned coffee, sparking a firefight in which every character is killed.[12] Tarantino described his vision for the character of Daisy Domergue as a "Susan Atkins of the Wild West".[13] Madsen based Joe Gage on Peter Breck's performance in The Big Valley.[14]

On April 19, 2014, Tarantino directed a live reading of the leaked script at the United Artists Theater in the Ace Hotel Los Angeles. The event was organized by the Film Independent at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) as part of the Live Read series and was introduced by Elvis Mitchell.[15] Tarantino explained that they would read the first draft of the script, and he added that he was writing two new drafts with a different ending. The actors who joined Tarantino included Samuel L. Jackson, Kurt Russell, Dern, Roth, Madsen, Walton Goggins, Zoë Bell, Amber Tamblyn, James Parks, James Remar, and Dana Gourrier.[16]

Casting

[edit]On September 23, 2014, it was revealed that Viggo Mortensen was in discussion with Tarantino for a role in the film.[17] Mortensen had passed on the film due to scheduling conflicts.[18] Tarantino met with Jennifer Lawrence about portraying Daisy Domergue, but she declined due to her commitments with Joy and The Hunger Games films.[19] On October 9, 2014, Jennifer Jason Leigh was added to the cast to play Daisy Domergue.[20] On November 5, 2014, it was announced that Channing Tatum was eyeing a major role in the film.[21] Later the same day, The Weinstein Company confirmed the cast in a press release, which would include Jackson, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Russell, Roth, Demián Bichir, Goggins, Madsen, and Dern. Tatum's casting was also confirmed.[22]

Later on January 23, 2015, TWC announced an ensemble cast of supporting members, including James Parks, Dana Gourrier, Zoë Bell, Gene Jones, Keith Jefferson, Lee Horsley, Craig Stark, and Belinda Owino.[23]

In the earlier public reading of the first script, the role of Daisy Domergue had been read by Amber Tamblyn, and the role of Bob, a Frenchman rather than a Mexican, was read by Denis Ménochet;[16] at the reading, the role of Jody was read by James Remar. Regarding the cast, Tarantino has said, "This is a movie where [bigger movie stars] wouldn't work. It needs to be an ensemble where nobody is more important than anybody else."[24]

Filming

[edit]On September 26, 2014, the state of Colorado had signed to fund the film's production with $5 million, and the complete film would be shot in Southwest Colorado.[25] A 900-acre ranch was leased to the production for the filming. There was a meeting on October 16, and the county's planning commission issued a permit for the construction of a temporary set.[25] Principal photography began in January 2015 near Telluride, Colorado.[26][27][28] The budget was reported to be $44–62 million.[5][29][30]

Antique guitar incident

[edit]We were informed that it was an accident on set... We assumed that a scaffolding or something fell on it. We understand that things happen, but at the same time we can't take this lightly. All this about the guitar being smashed being written into the script and that somebody just didn't tell the actor, this is all new information to us. We didn't know anything about the script or Kurt Russell not being told that it was a priceless, irreplaceable artifact from the Martin Museum.

The guitar destroyed by Russell's character was not a prop but an antique 1870s Martin guitar lent by the Martin Guitar Museum. According to sound mixer Mark Ulano, the guitar was supposed to have been switched with a copy to be destroyed, but this was not communicated to Russell; everyone on the set was "pretty freaked out" at the guitar's destruction, and Leigh's reaction was genuine, though "Tarantino was in a corner of the room with a funny curl on his lips, because he got something out of it with the performance."[32] Museum director Dick Boak said that the museum was not told that the script included a scene that called for a guitar being smashed, and determined that it was irreparable. The insurance remunerated the purchase value of the guitar. As a result of the incident, the museum no longer lends props to film productions.[31]

Cinematography

[edit]Cinematographer Robert Richardson, who also worked with Tarantino on Kill Bill: Volume 1 (2003), Kill Bill: Volume 2 (2004), Inglourious Basterds (2009), and Django Unchained, filmed The Hateful Eight on 65 mm, using three modern 65 mm camera models: the Arriflex 765 and the Studio 65 and the 65 HS from Panavision.[33] The film was transferred to 70 mm film for projection using Ultra Panavision 70 and Kodak Vision 3 film stocks: 5219, 5207, 5213 and 5203.[34] Until the release of Dunkirk two years later, it was the widest release in 70 mm film since Far and Away in 1992.[35] The film uses Panavision anamorphic lenses with an aspect ratio of 2.76:1, a very widescreen image that was used on some films in the 1950s and 1960s.[36] The production team also avoided any use of a digital intermediate in the 70 mm roadshow release, as this would have reduced the high native resolution of the format. It was color-timed photochemically by FotoKem, and the dailies were screened in 70 mm.[37] The wide digital release and a handful of 35 mm prints were struck from a digital intermediate, done by Yvan Lucas at Shed/Santa Monica.[38]

Post-production

[edit]Tarantino edited two versions of the film, one for the roadshow version and the other for general release. The roadshow version runs for two hours and fifty-two minutes, including a three minute overture and twelve minute intermission, and has alternate takes of some scenes. Tarantino created two versions as he felt some of the footage he shot for 70 mm would not play well on smaller screens.[39] The British Board of Film Classification records show the runtime difference between the Roadshow (187 minutes) and the DCP (168 minutes) releases was 19 minutes.[40][41]

Music

[edit]Tarantino announced at the 2015 San Diego Comic-Con that Ennio Morricone would compose the score for The Hateful Eight; it is the first Western scored by Morricone in 34 years, since Buddy Goes West, and Tarantino's first film to use an original score.[42][43] Tarantino had previously used Morricone's music in Kill Bill, Death Proof (2007; a part of the double-feature Grindhouse), Inglourious Basterds, and Django Unchained, and Morricone also wrote an original song, "Ancora Qui", for the last.[44] Morricone had previously made statements that he would "never work" with Tarantino after Django Unchained,[45] but ultimately changed his mind and agreed to score The Hateful Eight.[46] According to Variety, Morricone composed the score without even seeing the film.[47]

The soundtrack was announced on November 19, 2015, for a December 18 release from Decca Records. Morricone composed 50 minutes of original music for The Hateful Eight. In addition to Morricone's original score, the soundtrack includes dialogue excerpts from the film, "Apple Blossom" by The White Stripes from their De Stijl album, "Now You're All Alone" by David Hess from The Last House on the Left (1972) and "There Won't Be Many Coming Home" by Roy Orbison from The Fastest Guitar Alive (1967).[48]

Tarantino confirmed that the film would use three unused tracks from Morricone's original soundtrack for The Thing (1982)—"Eternity", "Bestiality", and "Despair"—as Morricone was pressed for time while creating the score.[49] The final film also uses Morricone's "Regan's Theme" from Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977).[50][51]

Morricone's score won several awards, including a special award from New York Film Critics Circle. The score won a Golden Globe for Best Original Score.[52] It also took the 2016 Academy Award for Best Motion Picture Score, Morricone's first after several career nominations.

The acoustic song played by Leigh's character Domergue on a Martin guitar is the traditional Australian folk ballad "Jim Jones at Botany Bay", which dates from the early 19th century and was first published by Charles McAlister in 1907.[53][verification needed] The rendition in the film includes lines which were not in MacAlister's version.[54] The film's trailer used Welshly Arms' cover of "Hold On, I'm Coming", although this is not used in the film itself.[55]

Release

[edit]

On September 3, 2014, The Weinstein Company (TWC) acquired the worldwide distribution rights to the film for a fall 2015 release.[56] TWC would sell the film worldwide, but Tarantino asked to personally approve the global distributors for the film.[57] In preparation for its release, Tarantino arranged for approximately 100[58] theaters worldwide to be retrofitted with anamorphic equipped 70 mm film projectors, in order to display the film as he intended.[36][59] The film was released on December 25, 2015, as a roadshow presentation in 70 mm film format theaters.[60] The film was initially scheduled to be released in digital theaters on January 8, 2016.

On December 14, The Hollywood Reporter announced that the film would see wide release on December 31, 2015, while still screening the 70 mm version.[61] The release date was moved to December 30, 2015, to meet demand.[62] On July 11, 2015, Tarantino and the cast of the film appeared at San Diego Comic-Con to promote the film.[42] In the UK, where the film was distributed by Entertainment Film Distributors, the sole 70 mm print in the country opened at the Odeon Leicester Square on January 8 in a roadshow presentation, with the digital general release version opening the same day at other cinemas, except Cineworld, who refused to book the film after failing to reach an agreement to show the 70 mm print.[63]

On December 20, 2015, screener copies of The Hateful Eight and numerous other Oscar contenders, including Carol, The Revenant, Brooklyn, Creed, and Straight Outta Compton, were uploaded to many websites. The FBI linked the case to co-CEO Andrew Kosove of Alcon Entertainment. Kosove responded that he had "never seen this DVD", and that "it never touched his hands."[64]

Home media

[edit]The Hateful Eight was released in the United States on Digital HD, and on Blu-ray and DVD on March 29, 2016, by The Weinstein Company Home Entertainment and Anchor Bay Entertainment.[65]

Extended version

[edit]On April 25, 2019, the streaming service Netflix released The Hateful Eight: Extended Version, an extended cut in the form of a miniseries split into four episodes.[66]

Stage adaptation

[edit]In early 2016, Tarantino announced that he planned to adapt The Hateful Eight as a stage play.[67]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The Hateful Eight grossed $54.1 million in the United States and Canada and $107.1 million in other countries, for a worldwide total of $161.2 million.[5]

It opened in the US with a limited release on December 25, 2015, and over the weekend, it grossed $4.9 million from 100 theaters ($46,107 per screen), finishing 10th at the box office.[68] It had its wide release on December 30, grossing $3.5 million on its first day.[69] The film went on to gross $15.7 million in its opening weekend, finishing third at the box office, behind Star Wars: The Force Awakens ($90.2 million) and Daddy's Home ($29.2 million).[70]

Critical response and analysis

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, The Hateful Eight holds an approval rating of 75% based on 336 reviews, with an average rating of 7.3/10. Its critical consensus reads, "The Hateful Eight offers another well-aimed round from Quentin Tarantino's signature blend of action, humor, and over-the-top violence – all while demonstrating an even stronger grip on his filmmaking craft."[71] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned The Hateful Eight a score of 68 out of 100 based on 51 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[72] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B" on an A+ to F scale, while PostTrak reported audiences gave it a 42% "definite recommend".[69]

James Berardinelli wrote that The Hateful Eight "is a high-wire thriller, full of masterfully executed twists, captivating dialogue, and a wildly entertaining narrative that gallops along at a pace to make three hours evaporate in an instant. Best film of the year? Yes."[73] Telegraph critic Robbie Collin wrote: "The Hateful Eight is a parlour-room epic, an entire nation in a single room, a film steeped in its own filminess but at the same time vital, riveting and real. Only Tarantino can do this, and he's done it again."[74] The Guardian critic Peter Bradshaw gave the film five out of five, and wrote that it was "intimate yet somehow weirdly colossal, once again releasing [Tarantino's] own kind of unwholesome crazy-funny-violent nitrous oxide into the cinema auditorium for us all to inhale ... "Thriller" is a generic label which has lost its force. But The Hateful Eight thrills."[75] A.V. Club critic Ignatiy Vishnevetsky gave the film a grade of A− and wrote that "with a script that could easily be a stage play, The Hateful Eight is about as close as this pastiche artist is likely to get to the classical tradition."[76]

In contrast, Owen Gleiberman of the BBC said, "I'm not alone in thinking that it's Tarantino's worst film – a sluggish, unimaginative dud, brimming with venom but not much cleverness."[77] Donald Clarke, writing in The Irish Times, wrote, "What a shame the piece is so lacking in character and narrative coherence. What a shame so much of it is so gosh-darn boring."[78] A. O. Scott in The New York Times said, "Some of the film's ugliness...seems dumb and ill-considered, as if Mr. Tarantino's intellectual ambition and his storytelling discipline had failed him at the same time."[79] Todd McCarthy of The Hollywood Reporter praised the film's production design, idiosyncratic dialogue, and "lip-smackingly delicious" performances, but felt the film was overlong and that Morricone's score was put to too limited use.[80]

Scholars Florian Zitzelsberger and Sarah E. Beyvers observe that the film follows Aristotle's unities: "Tarantino's film meticulously adheres to the classical unities of a tragedy, which had been seen as a necessity for the audience's immersion for a long time: 'The Hateful Eight' follows only one plot (unity of action), it is limited to a time period of 24 hours (unity of time)."[81] Hollis Robbins argues that The Hateful Eight is a panoramic Western chamber drama: "Tarantino's eighth film demands to be seen not as a revisionist but a newly visioned western, using the mythmaker's tools to offer a panoramic vision of racial sovereignty undone by random violence."[82]

Top ten lists

[edit]The Hateful Eight was listed on many critics' top ten lists.[83]

- 1st – James Berardinelli, Reelviews

- 2nd – Scott Feinberg, The Hollywood Reporter

- 2nd – Peter Sobczynski, RogerEbert.com

- 3rd – Amy Nicholson, L.A. Weekly

- 4th – Jack Giroux, Collider.com

- 4th – Marlow Stern, The Daily Beast

- 5th – Jacob Hall, Collider.com

- 6th – Connie Ogle, Miami Herald

- 6th – Richard Roeper, Chicago Sun-Times

- 7th – Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, The A.V. Club

- 8th – Drew McWeeny, Hitfix

- 8th – Ben Kenigsberg, RogerEbert.com

- 8th – Matt Singer, ScreenCrush

- 8th – Kristopher Tapley, Variety

- 9th – Stephen Schaefer, Boston Herald

- 9th – Rene Rodriguez, Miami Herald

- 9th – Scott Tobias, Village Voice

- 9th – Glenn Kenny & Brian Tallerico, RogerEbert.com

- 10th – Jeff Cannata, Collider.com

- Top 10 (ranked alphabetically) – Brian Truitt, USA Today

- Top 10 (ranked alphabetically) – Joe Leydon, Variety

Attempted police boycott

[edit]In October 2015, Tarantino attended a Black Lives Matter rally and publicly commented on police brutality in the United States, saying, "When I see murders, I do not stand by... I have to call a murder a murder, and I have to call the murderers the murderers." Tarantino's comments received national media attention, and several police groups in the United States pledged to boycott The Hateful Eight and his other films. Tarantino responded that he was not a "cop hater" and would not be intimidated by the calls for a boycott.[84][85]

Forbes said that the film, while not as commercially successful as some of Tarantino's other films, cast doubt on claims that a boycott had a strong effect on sales.[86]

Race issues

[edit]Tarantino told GQ that race issues were part of his creative process and were inescapable, saying: "I wasn't trying to bend over backwards in any way, shape, or form to make it socially relevant. But once I finished the script, that's when all the social relevancy started."[87] He told The Telegraph he wrote The Hateful Eight to reflect America's fraught racial history, with the splitting of the cabin into northern and southern sides and a speech about the perils of "frontier justice".[88] A. O. Scott of The New York Times observed that the film rejects the Western genre's tradition of ignoring America's racial history, but felt its handling of race issues was "dumb and ill-considered", and wrote: "Tarantino doesn't make films that are 'about race' so much as he tries to burrow into the bowels of American racism with his camera and his pen. There is no way to do that and stay clean."[79]

Gender issues

[edit]Some critics expressed an unease at the treatment of the evil and sadistic Daisy Domergue character, who is the subject of repeated physical and verbal abuse and finally hanged in a sequence, which, according to Matt Zoller Seitz of RogerEbert.com, "lingers on Daisy's death with near-pornographic fascination".[89][90][91] A. O. Scott felt the film "mutates from an exploration of racial animus into an orgy of elaborately justified misogyny".[79] Laura Bogart regarded the treatment of Daisy Domergue as a "betrayal" of the positive female characters in previous Tarantino films, such as Kill Bill.[92] Juliette Peers wrote that "compared to the stunning twists and inversions of norms that Tarantino's other works offer when presenting female characters, The Hateful Eight's sexual politics seem bleakly conservative. Daisy is feisty and highly intelligent, yet the plotline is arbitrarily stacked against her."[91]

Conversely, Courtney Bissonette of Bust praised Tarantino's history of female characters and wrote of Domergue's treatment: "This is equality, man, and it's more feminist to think that a criminal is getting treated the same despite her sex. They don't treat her like a fairy princess because she is a woman, they treat her like a killer because she is a killer."[93] Sophie Besl of Bitch Flicks argued that Domergue received no special treatment as a woman, is never sexually objectified, and has agency over her own actions (including killing her captor). She defended the hanging scene as in the filmic tradition of villains "getting what's coming to [them]", and that equivalent scenes with male villains in previous Tarantino films raised no objections.[94] However, Matthew Stogdon felt that as Domergue's crimes are not explained, her status as a criminal deserving execution is not established, breaking the narrative rule of "show, don't tell".[95]

Walton Goggins described the two survivors cooperating in the hanging as symbolic of a positive step to erase racism: "I see it as very uplifting, as very hopeful, and as a big step in the right direction, as a celebration, as a changing of one heart and one mind."[96] However, Sasha Stone, writing for Awards Daily, felt it was implausible for Domergue to "represent, somehow, all of the evil of the South, all of the racism, all of the injustice. She's a tiny thing. There is no point in the film, or maybe one just barely, when Daisy inflicts any violence upon anyone – and by then it could be argued that she is only desperately trying to defend herself. She is handcuffed to Kurt Russell, needing his permission to speak and eat, and then punched brutally in the face whenever she says anything."[97]

Tarantino intended the violence against Domergue to be shocking and wanted the audience's allegiances to shift during the story. He said: "Violence is hanging over every one of those characters like a cloak of night. So I'm not going to go, 'OK, that's the case for seven of the characters, but because one is a woman, I have to treat her differently.' I'm not going to do that."[98]

Accolades

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ McCarthy, Todd (December 15, 2015). "'The Hateful Eight': Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "The Hateful Eight (2015)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- ^ "The Hateful Eight". Pharos. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ "The Hateful 8". The Hateful 8. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "The Hateful Eight". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "The Hateful Eight". The Numbers. Archived from the original on January 2, 2022. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (November 27, 2013). "Quentin Tarantino says next film will be another western". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on November 10, 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2015.

- ^ Staskiewicz, Keith (December 11, 2015). "Quentin Tarantino explains how Hateful Eight began as a Django novel". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 4, 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- ^ Kit, Borys (January 11, 2014). "Quentin Tarantino's New Movie Sets Title, Begins Casting". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (November 10, 2014). "Quentin Tarantino on Retirement, Grand 70 MM Intl Plans For 'The Hateful Eight". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Fleming, Mike Jr. (January 21, 2014). "Quentin Tarantino Shelves 'The Hateful Eight' After Betrayal Results in Script Leak". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- "Quentin Tarantino sues Gawker over Hateful Eight script leak". CBC News. January 21, 2014. Archived from the original on February 18, 2016. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- Gettell, Oliver (January 22, 2014). "Quentin Tarantino mothballs 'Hateful Eight' after script leak". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 12, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "The Hateful Eight Script Leak: 8 Spoilers From Quentin Tarantino's Western". WhatCulture.com. January 24, 2014. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ Truitt, Brian (December 23, 2015). "Jennifer Jason Leigh gives life to devilish Daisy in 'Hateful Eight'". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 28, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ Kane, Elric; Saur, Brian; McLean, Julie (February 17, 2020). "Michael Madsen". Pure Cinema (Podcast). Event occurs at 1:24:00-1:25:00. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ "World Premiere of a Staged Reading by Quentin Tarantino: The Hateful Eight". LACMA.org. April 19, 2014. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ a b Anderton, Ethan (April 21, 2014). "Tarantino's 'Hateful Eight' Live-Read Reveals Script Still Developing". FirstShowing.net. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Garvey, Marianne; Niemietz, Brian; Coleman, Oli (September 23, 2014). "Viggo Mortensen and Quentin Tarantino talk business, and director gets closeup with Vanessa Ferlito". Daily News. New York City. Archived from the original on September 24, 2014. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- ^ Rahman, Abid (March 23, 2015). "Viggo Mortensen on 'Hateful Eight': "I Wish It Had Worked Out"". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ "When Quentin Met J-Law... To discuss 'The Hateful Eight'". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Sneider, Jeff (October 9, 2014). "Quentin Tarantino Casts Jennifer Jason Leigh as Female Lead in 'Hateful Eight'". TheWrap.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (November 5, 2014). "Channing Tatum Eyes 'Hateful Eight' Role". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ^ Ramisetti, Kirthana (November 6, 2014). "'The Hateful Eight' cast announced: Samuel L. Jackson, Jennifer Jason Leigh and Channing Tatum among all-star cast in Quentin Tarantino's latest film". Daily News. New York City. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ "Filming Starts for Quentin Tarantino's The Hateful Eight". ComingSoon.net. January 23, 2015. Archived from the original on January 23, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- ^ Brown, Lane (August 23, 2015). "In Conversation: Quentin Tarantino". Vulture.com. Archived from the original on August 24, 2015. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Lisa; Svaldi, Aldo (September 26, 2014). "Quentin Tarantino set to shoot 'Hateful Eight' in Colorado". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ^ Lewis, Andy (January 7, 2016). "Making of 'Hateful Eight': How Tarantino Braved Sub-Zero Weather and a Stolen Screener". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Dyer, Kyle (December 10, 2014). "New Tarantino movie starts filming near Telluride". 9News. Multimedia Holdings Corporation. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ McNary, Dave (January 23, 2015). "Quentin Tarantino Starts Shooting 'Hateful Eight'". Variety. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ^ Lang, Brent (January 3, 2016). "Harvey Weinstein Talks 'Hateful Eight': 'Star Wars' Took a Bite Out of Box Office". Variety. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ Tobias, Scott (December 24, 2015). "Tarantino Holes Up A Few Outlaws In 'The Hateful Eight'". NPR. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ a b "Martin Responds to "Hateful Eight" Destruction of Antique Six String". reverb.com. February 4, 2016. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ ""The Hateful Eight" Hates on Six Strings: Film Includes Real Destruction of Antique Martin". reverb.com. February 2, 2016. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "The Hateful Eight (2015)". IMDb. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2020 – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ "Large Format: Ultra Panavision 70 - The American Society of Cinematographers". ascmag.com. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ Pucho, Kristy (September 2014). "Quentin Tarantino's Hateful Eight To Be Widest 70 mm Release in 20 Years". CinemaBlend.com. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Fischer, Russ (June 8, 2015). "Quentin Tarantino Helps Get 70mm Projectors in 50 Theaters for 'The Hateful Eight'". /Film. Archived from the original on June 8, 2015. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ Desowitz, Bill (December 8, 2015). "How Quentin Tarantino Resurrected Ultra Panavision 70 for 'The Hateful Eight' Roadshow". Thompson on Hollywood (Indiewire.com). Archived from the original on December 23, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Prince, Ron (February 4, 2016). "Robert Richardson ASC / The Hateful Eight". British Cinematographer.

- ^ Tapley, Kristopher (October 13, 2015). "Quentin Tarantino Says He Cut Two Different Versions of 'The Hateful Eight'". Variety. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ^ "The Hateful Eight 70Mm Version". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "The Hateful Eight". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Lincoln, Ross A. (July 11, 2015). "Quentin Tarantino Delivers Mind-Blowing Look At 'Hateful Eight' – Comic Con". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on October 1, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Johnston, Raymond (July 19, 2015). "Tarantino and Morricone settle the score in Prague". The Prague Post. Archived from the original on July 20, 2015. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ "'Django Unchained' Soundtrack Details". Film Music Reporter. November 28, 2012. Archived from the original on March 16, 2016. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ Lyman, Eric J. (March 15, 2013). "Italian Composer Ennio Morricone: I'll Never Work With Tarantino Again". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 14, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ Anderson, Ariston (January 30, 2016). "Ennio Morricone Accepts Golden Globe for 'The Hateful Eight' in Rome". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ Tapley, Kristopher (February 28, 2016). "Legendary Composer Ennio Morricone Wins Original Score Oscar for 'Hateful Eight'". Variety. Archived from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ^ "'The Hateful Eight' Soundtrack Details". Film Music Reporter. November 19, 2015. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ "Quentin Tarantino Reveals 'Hateful Eight' Score Features Unused Music By Ennio Morricone From John Carpenter's 'The Thing'". The Playlist (Indiewire.com). Archived from the original on December 13, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ^ Coffel, Chris (December 30, 2015). "[Review] 'The Hateful Eight' is a Masterful Display of Cinematic Craftsmanship". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ Weingarten, Christopher R.; Soderberg, Brandon; Smith, Steve; Beta, Andy; Battaglia, Andy; Grow, Kory; Orlov, Piotr; Epstein, Dan (October 18, 2019). "35 Greatest Horror Soundtracks: Modern Masters, Gatekeepers Choose". Rolling Stone.

- ^ "Ennio Morricone, Ryuichi Nakamoto nominated for Golden Globes". factmag.com. December 10, 2015. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ Charles MacAlister, Old Pioneering Days in the Sunny South (1907), "Jim Jones at Botany Bay" (1 text)

- ^ Ron Edwards, The Big Book of Australian Folk Song

- ^ "What's The Song On The Hateful Eight Trailer?". Daystune. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ "Weinsteins Will Distribute Quentin Tarantino's 'Hateful Eight' Worldwide". Deadline Hollywood. September 3, 2014. Archived from the original on September 5, 2014. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ Roxborough, Scott (February 9, 2015). "Berlin: Quentin Tarantino Personally Approving Buyers of 'Hateful Eight'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 11, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ Kenigsberg, Ben (November 11, 2015). "Tarantino's 'The Hateful Eight' Resurrects Nearly Obsolete Technology". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 30, 2015. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ Bernstein, Paula (June 9, 2015). "Quentin Tarantino to Retrofit Theaters to Accommodate 'Hateful Eight' in 70mm". Indiewire.com. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (June 12, 2015). "'Hateful Eight' To Hit Theaters Christmas Day in 70MM". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ Galuppo, Mia (December 14, 2015). "'Hateful Eight' Getting Nationwide Release on Dec. 31". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ^ Lincoln, Ross A. (December 29, 2015). "'Hateful Eight' Gets Early Digital Expansion: 1900+ Screens Starting Tonight". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on December 30, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ Lee, Benjamin (January 5, 2016). "The Hateful Eight: not showing near you at three key UK cinema chains". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 12, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ Ricker, Thomas (December 24, 2015). "Hollywood's Christmas is being ruined by unprecedented leaks". The Verge. Archived from the original on July 12, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- ^ "The Hateful eight (2015)". DVDs ReleaseDates. July 2019. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019.

- ^ Hoffman, Jordan (April 27, 2019). "Why has Tarantino turned The Hateful Eight into a Netflix miniseries?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- ^ Joe Otterson (January 10, 2016). "Quentin Tarantino Plans to Make 'Hateful Eight' Into a Play". The Wrap. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony; Busch, Anita (December 28, 2015). "'Star Wars' Flies To $540M in Second Best Box Office Weekend of All Time". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ a b Lowe, Kinsey (December 31, 2015). "'Star Wars' Now 4th-Biggest Domestic Grosser on Way To $700M; 'Hateful Eight' Adds $3.5M in 1st Day of Expansion". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony; Busch, Anita (January 4, 2016). "'Force Awakens' Will Beat 'Avatar' Domestic Record Tuesday; New Year's Weekend $219.3M Ticket Sales 2nd Best All-Time". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ "The Hateful Eight". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved July 6, 2024.

- ^ "The Hateful Eight". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (December 22, 2015). "Hateful Eight, The (United States, 2015)". ReelViews. Archived from the original on April 22, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ Collin, Robbie (January 7, 2016). "The Hateful Eight review: 'only Tarantino can do this'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (December 16, 2015). "The Hateful Eight review: Agatha Christie with gags, guns and Samuel L Jackson". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 21, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ Vishnevetsky, Ignatiy (December 16, 2015). "Quentin Tarantino gets theatrical in the 70mm Western The Hateful Eight". AVClub.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (December 18, 2015). "Is The Hateful Eight Tarantino's Worst?". BBC News. Archived from the original on December 29, 2015. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ Clarke, Donald (January 7, 2016). "The Hateful Eight review: The wheels come off the wagon". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ a b c Scott, A. O. (December 24, 2015). "Review: Quentin Tarantino's 'The Hateful Eight' Blends Verbiage and Violence". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (December 15, 2015). "'The Hateful Eight': Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ Zitzelsberger, Florian; Beyvers, Sarah E. (July 1, 2018). "Revisionist Spectacle? Theatrical Remediation in Alejandro G. Iñárritu's Birdman and Quentin Tarantino's The Hateful Eight". Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies. 18 (1): 3–21. doi:10.17077/2168-569X.1482. ISSN 2168-5738.

- ^ Robbins, Hollis. "U.S. History in 70 MM: 'The Hateful Eight' (2015). Directed by Quentin Tarantino." The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, vol. 15, no. 3, 2016, pp. 368-370

- ^ http://www.metacritic.com/feature/film-critics-list-the-top-10-movies-of-2015

- ^ Whipp, Glenn (November 4, 2015). "Quentin Tarantino responds to police boycott calls: The complete conversation". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2015.

- ^ Kludt, Tom (November 3, 2015). "Quentin Tarantino won't be 'intimidated' by police boycott". CNN. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ Mendelson, Scott (January 18, 2016). "No, Police Boycotts Against Quentin Tarantino didn't cause 'Hateful Eight' to Flop". Forbes. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- ^ Barksdale, Adam (December 8, 2015). "Quentin Tarantino on White Supremacy And Black Lives Matter". Huffington Post Australia. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ "Quentin Tarantino: 'the Confederate flag was the American Swastika'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ Seitz, Matt Zoller. "The Hateful Eight". RogerEbert.Com. Archived from the original on April 1, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ Nayman, Adam (2015). "You've Gotta Be...Kidding Me: Quentin Tarantino's The Hateful Eight". Cinema Scope Online. Canada: Cinema Scope Magazine. Archived from the original on February 26, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Peers, Juliette (January 24, 2016). "'Elaborately justified misogyny': The Hateful Eight and Daisy Domergue". The Conversation. The Conversation US. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ Bogart, Laura (January 18, 2016). "Hipster Misogyny: The Betrayal of "The Hateful Eight"". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on March 20, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ Bissonette, Courtney. "A Feminist Defense of Quentin Tarantino". Bust. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ Besl, Sophie (January 8, 2016). "Let's All Calm Down for a Minute About 'The Hateful Eight': Analyzing the Leading Lady of a Modern Western". Bitch Flicks. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ Stogdon, Matthew. "THE HATEFUL EIGHT No One To Trust, Everyone To Hate". The Red Right Hand Movie Reviews. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016.

- ^ Sullivan, Kevin P. (January 5, 2016). "The Hateful Eight ending spoilers: Walton Goggins interview". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Stone, Sasha (December 27, 2015). "The Hateful Eight, Tarantino and that Misogyny Word". AwardsDaily. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Tapley, Kristopher. "Claims of 'Hateful Eight' Misogyny 'Fishing for Stupidity,' Harvey Weinstein Says". Variety. Archived from the original on December 21, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

External links

[edit]- 2015 films

- 2015 Western (genre) films

- 2015 thriller films

- American nonlinear narrative films

- American Western (genre) films

- American thriller films

- BAFTA winners (films)

- Films directed by Quentin Tarantino

- Films scored by Ennio Morricone

- Films about death

- Films about race and ethnicity

- Films set during snowstorms

- Films set in the American frontier

- Films set in Wyoming

- Films shot in Colorado

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Quentin Tarantino

- The Weinstein Company films

- Revisionist Western (genre) films

- 2010s English-language films

- 2010s American films

- English-language Western (genre) films

- English-language thriller films