The Chimera Brigade

| The Chimera Brigade | |

|---|---|

Chimeric Brigade logo. | |

| Author(s) | Serge Lehman, Fabrice Colin |

| Illustrator(s) | Stéphane Girard |

| Publisher(s) | L'Atalante |

| Genre(s) | Steampunk, Fantastique |

| Original language | French |

The Chimera Brigade is a French comic book series by scriptwriters Serge Lehman and Fabrice Colin, illustrator Gess and colorist Céline Bessonneau. The six-volume series was published by L'Atalante between August 2009 and October 2010.

The story takes place on the eve of the Second World War, in a Europe where superhumans are thriving, having appeared on the battlefields of the First World War, amidst gas and X-rays. Summoned by Doctor Mabuse to the heart of the Austrian Alps, they watch helplessly as his plans for European domination unfold. In France, while the Nyctalope, the new protector of Paris since the death of Marie Curie, abandons international politics, the Joliot-Curie, aware of the German danger, turn to Jean Séverac. This amnesiac man, who had once worked with Marie Curie at the Radium Institute, could be the key to leading the resistance against the takeover of Europe by Doctor Mabuse and his allies, Gog in Italy, the Phalange in Spain and the troubled "Nous Autres" in the East.

By revisiting the rise of Nazism, the series aims to use fantastic allegory to explain the disappearance of superheroes in Europe, and the fact that their very existence was obscured from collective memory in the aftermath of the war. While establishing a causal link between the end of European supermen and the emergence of American superheroes, the authors pay homage to the European anticipation of the interwar period, multiplying literary references to works that have fallen into oblivion.

Awarded the Grand prix de l'Imaginaire in 2011 in the "Comics" category, the series has been extended several times, with a role-playing game adaptation and comic book series set before the events L'Homme truqué, L'Œil de la Nuit) or long after (Masqué, La Brigade chimérique – Ultime Renaissance).

Development

[edit]Origins

[edit]

The origins of the Chimera Brigade series lie in science-fiction author Serge Lehman's awareness, in the 1990s, of a paradoxical fact: science fiction is perceived as an essentially American genre, even though the genre existed and flourished in late 19th- and 20th-century Europe, and particularly in France. Yet this European science fiction, a literary genre featuring supermen, completely disappeared from the collective imagination after the Second World War.[1]

With this in mind, in the late 1990s, Serge Lehman drew up a project for an uchronistic novel dedicated to the city of Metropolis, in which he planned to depict the French supermen of the 1920s and 1930s and retrace their disappearance from the collective imagination. But the sheer scale of the task prevented the project from coming to fruition.[2]

The project was relaunched in 2005, when he took part in the launch of the Flambant Neuf comics collection by éditions L'Atalante. Lehman told the publisher of his wish to tell the story of the disappearance of European superheroes through a comic book series, and the publishing house then contacted Gess for the design.[3] To bring his project to fruition, Serge Lehman enlisted the help of novelist Fabrice Colin to write the screenplay.[2] The team also enlisted the services of colorist Céline Bessonneau, whose name appears on the cover and is indistinguishable from those of the scriptwriters and illustrator.[4]

Through this series the authors set out to explain the disappearance of European superheroes from the collective memory, in favor of the over-exploitation of their cousins on the other side of the Atlantic.[5] Indeed, unlike in the USA, where the genre remains fertile and capable of regular renewal, in France, stories about supermen disappeared in the aftermath of the Second World War, also obscuring all the French anticipation of the interwar period.[6]

In explaining this disappearance, The Chimera Brigade reinvests the literary genre by featuring fictional characters who had their heyday in the early 20th century alongside historical figures from literary and scientific circles.[7] In addition to paying homage to the French authors who pioneered modern science fiction by revitalizing their works,[8] The Chimera Brigade also aims to make the genre more familiar to readers, so that French authors can take their turn in superhero stories.[9]

The name of the series is a tribute to the Brigades du Tigre, the French mobile police force of the early 20th century popularized by the TV series of the same name, to the International Brigades and to the use of the word "chimera" regularly employed by pre-war authors.[6]

To recapture the spirit of pre-war soap operas and comic books, Serge Lehman initially sought to publish the series on newsstands in the form of monthly issues. However, for commercial reasons, the publisher convinced him to adopt an intermediate formula: six hardcover albums, each containing two episodes, published over the space of a year.[10]

Creative context

[edit]Since the beginning of the 21st century the series has been part of a rediscovery of a whole part of the French-speaking literary heritage, not only of the scientific marvelous genre, but more broadly of the popular serial novel.[11]

Serge Lehman contributed to this revival with his seminal article Les mondes perdus de l'anticipation française, published in Le Monde diplomatique in 1999, in which he lamented the neglect of turn-of-the-century French science fiction; then with his book Les Chasseurs de chimères, published in 2006, which brings together a large number of texts from the period, and goes on to reflect on the genre.[12]

This rediscovery is also accompanied by a reappropriation of this heritage by French authors interested in certain figures from the popular literature of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,[13] not least thanks to the fact that the stories of many heroes are beginning to fall into the public domain. In this respect, the work of publisher Jean-Marc Lofficier within the Rivière Blanche collection has made it possible to feature many famous or forgotten heroes of popular literature in the short story anthologies Les Compagnons de l'Ombre.[14] This in-depth work is as much a tribute as a contemporary reinterpretation.[15]

In addition to literature, comics are also a very dynamic medium for the recognition of the scientific marvelous;[16] in fact, since the beginning of the 21st century, the super-heroic theme has been tackled more and more, and in a more complex way, by various authors,[17] such as the series Les Sentinelles by Xavier Dorison and Enrique Breccia, published three months before the release of La Brigade chimérique. This series recounts the military adventures of mechanically-enhanced super-soldiers during the Great War, wounded by their sacrifice.[14]

This renewed interest also seems to be part of the wider steampunk movement, an uchronistic literary genre that emerged in the 1990s, revisiting a past – initially that of the 19th century – in which technological progress has accelerated and crystallized.[18]

When the first volume came out in 2009, comparisons were often made with Alan Moore's 1999 work The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, in which the English author recreated a universe in which numerous fictional heroes from the late 19th and early 20th centuries lived side by side. Indeed, to avoid being accused of plagiarism, Lehman is said to have delayed writing The Chimera Brigade. However, beyond the principle of reusing literary characters, the two works differ in their narrative objectives. While Alan Moore uses literary heroes in the face of purely fictional threats, Lehman uses literary characters in a teleological vision that aims to explain their disappearance from collective memory.[7] To this end, he reworks all literary and historical characters to serve an original story, recounting the disappearance of European superheroes.[19]

Between inspiration and literary hoax

[edit]

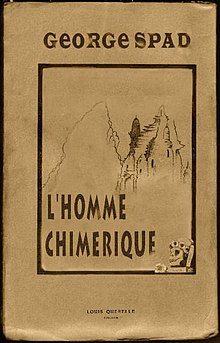

In the appendix to the complete edition of La Brigade chimérique, devoted to the origins of the comic strip, Serge Lehman claims two major sources of inspiration: novelist J.-H. Rosny aîné's L'Énigme de Givreuse and mysterious novelist George Spad's L'Homme chimérique.

Both novels explore the experience of molecular separation. The first, L'Énigme de Givreuse, was published in 1916 and tells the story of Pierre de Givreuse, who finds himself split into two amnesiac entities. In his novel, Rosny addresses the question of memory and the consequences of amnesia.[20] Serge Lehman pays explicit homage to the novel with a cameo by the de Givreuse twins, depicted in conversation with the Atlantean Sun-Koh, the hero of German writer Paul Alfred Müller.[21]

The comic strip also makes explicit reference to the second novel, George Spad's L'Homme chimérique, both in the title and in the leading role of the character George Spad in the series. Serge Lehman refers extensively to this novelist in his note appended to the unabridged edition.[22] He explains that George Spad – or George Spadd – was in fact a collective pseudonym used initially by Renée Dunan, then by a friend of hers from 1924 onwards, Huguette Blanche Perrier.[23] He reveals that this 1919 novel, published by Louis Querelle, tells the story of Captain Jean Brun de Séverac, who disappeared in the trench warfare of the First World War, reappearing in the form of four characters: a teenager, a bearded, hairy giant, a skeletally thin bald man and a young woman. George Spad depicts the four heroes as each being an element of Séverac's personality. Lehman goes on to say that this novel was followed by a monthly serial entitled George Spadd's Pirates du Radium, published between September 1924 and February 1925. The series then ended with the announcement of a never-published adventure: The Chimeric Brigade vs. Dr. Mabuse. Lehman and Colin's The Chimera Brigade was a direct sequel to Pirates du Radium[23].

Information on the novelist's very sketchy biographical details comes from the website of the "Société des amis de George Spad", to which the essayists Joseph Altairac and Guy Costes seem to be close.[24] In reality, however, this source of inspiration claimed by Serge Lehman, whose adventures fit in perfectly with the series' plot, is a literary hoax set up by the authors in the mid-2000s.[25] In fact, during the preparatory work for La Brigade chimérique, Lehman wrote a text that was to serve as a preface to the comic strip, in which he presented the series as the continuation of a novelistic cycle from the 1920s. Although this preface was not retained, the character of George Spad was nonetheless included in the script as a heroine.a 4 Finally, in June 2021, novelist Christine Luce made the deception public, revealing her role and that of three other essayists and novelists (Philippe Ethuin, Joseph Altairac and Guy Costes) in the mystification. This revelation precedes the publication of the novel in September 2021 by Editions Moltinus. In a literary mise en abyme, Christine Luce wrote – under the name George Spad – the novel, which was eventually renamed Renée Dunan contre les mutants.[26]

Setting

[edit]"Metaphorization" of history

[edit]

By featuring imaginary vehicles and technologies, the world of The Chimera Brigade is described as "radiumpunk" by its creators. This word, derived from the term steampunk, highlights its relationship to the mastery of radium, whose discovery by Marie Curie serves as a temporary point of historical divergence. Thus, while steampunk, as its name suggests, is defined by its mastery of steam, radiumpunk is distinguished by its mastery of radioactivity.[27]

The series is described as a "fantastic allegory" in that, although it is initially presented as an uchrony, it joins historical reality in 1939.[7] Serge Lehman and Fabrice Colin set out to base the chronology of the story on real history, while incorporating all the issues they felt were linked to the theme of the superman, from Marie Curie's research on radium to Nazi rhetoric on the superman.[28]

The authors also endeavored to respect the geopolitical chronology of interwar Europe: the Bolshevik Revolution, the Weimar Republic, the Spanish Civil War, while reinterpreting these events through a conflictual prism of superhero and supervillain.[29] Each symbolically represents the efforts and wills, but also the impotence and cowardice, that led up to the Second World War in the 1930s.[30] The Shoah itself is integrated as the climax of the story, insofar as the authors place the extermination of the Jews in the super-scientific world of comics. They also give the word "holocaust" a concrete meaning, since Metropolis, the true symbol of Mabuse's regime, is built on the sacrifice of the Jews.[31] Through this rereading of history, Lehman and Colin recount "a historical reality augmented by its imaginary".[32]

Geopolitical context

[edit]

The world of The Chimera Brigade takes place in Europe at the end of the 1930s. While the authors respect the European geopolitical context on the eve of the Second World War, they adapt it to include fictional characters, placing the main capitals under the responsibility of supermen.[9] These characters were chosen from the heroes of interwar popular literature to embody the three poles of the impending global conflict: fascists, communists and democracies.[2]

Germany is in the hands of Dr. Mabuse, a man capable of hypnotizing crowds. His organization borrows its symbolism from the Nazi party, with skeleton men as SS, and Hitler implicit in all his speeches.[30] Created in 1921 by novelist Norbert Jacques, Dr. Mabuse is a German criminal and archetypal "evil genius", like his contemporaries Fu Manchu and Fantômas, whose mastery of telepathic hypnosis enables him to enslave his victims.[33] He was popularized by Fritz Lang's films of the 1920s and 1930s, which Lehman and Colin drew on for their implicit Nazi content in designing the character and his warmongering plans. In addition to the initial "M" they share, the films Mabuse, M le maudit and Metropolis bear witness to the Austro-German filmmaker's anti-Nazi stance.[34] The play on onomastics even goes so far as to make Metropolis his capital city.[35]

To portray Mabuse's European allies, the authors had more difficulty, as literature from Latin countries had very few superheroes.[2] To embody fascist Italy, they opted for the character of Gog, taken from the 1931 novel of the same name by Italian writer Giovanni Papini, who was close to Fascism. This wealthy, cynical, nihilistic figure, who holds the financial reins of Italy, contrasts with his Spanish ally, "La Phalange". The latter, a Francoist superman born in the trenches, is an allegorical character invented for the purposes of the story.[35] Master of Spain, the Phalange must nonetheless contend with guerrilla warfare led by a revolutionary hero called "the Partisan". This enigmatic character is conceived as a pure archetype, however, and appears only on a poster, in George Spad's memoirs and at the end of the series, on the London docks, illustrating his refusal to leave the European continent.[36] The authors of the Encyclopedia of The Chimera Brigade later developed the character, describing him as a "hero without power", egalitarian and claiming to be George Orwell.[37]

To the east of these noxious powers, conceived by the authors as the "super-villains of the age",[8] is the ambiguous "We Others". An illustration of the USSR, this Soviet organization is made up of faceless, powerless men and women, some of whom pilot mechanical exoskeletons that make them capable of rivaling superhumans. Based on the novel We by Russian writer Ievgueni Zamiatine, this regime is led by a robot with a face reminiscent of Stalin, called "Big Brother" in reference to George Orwell's Big Brother from 1984.[35] Faced with these regimes, the Western democracies tried to save the peace in Europe. On the eve of global conflict, however, their pathetic attempts to save the peace, even if it meant putting their honor on the line, seemed outdated.[31]

Since the First World War, Marie Curie, nicknamed the "Queen of Radium", has been at the head of the Radium Institute, where she takes in soldiers who have fallen victim to chemical experiments in the trenches. Cared for, studied and often trained, these supermen, who had developed extraordinary aptitudes, threw themselves into heroism under her guidance. When she died in 1934, she appointed the Nyctalope as the new protector of Paris through her organization, the Comité d'Information et de Défense (CID), based in Montmartre.[38] Marie Curie's scientific legacy was inherited by her daughter and son-in-law, Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie, who jointly took over the management of her institute.

England is represented by Andrew Gibberne, a superman capable of high-speed travel, who accompanies the Nyctalope on his journeys abroad. The authors present him as the son of Professor Gibberne, hero of H. G. Wells's short story The New Accelerator (1901).[35] As allies of these European democracies, the United States plays only a spectator role, although at the end of the series it welcomes the heroes fleeing Mabuse's victory in Europe. Present when Mabuse is summoned to Metropolis, the American delegation includes Mr. Steele aka Superman, The Shadow and Dr. Savage.

Superheroic context

[edit]

Serge Lehman draws on his erudition of early 20th-century popular literature to structure a fictional universe around numerous literary references; far from being anecdotal, he uses these references to reflect on the history of European science fiction.[4]

In forging his concept of the Hyperworld, a veritable collective unconscious in which all fictional characters are immersed, Lehman places "the Plasma" at the heart of his work.[39] This term, which does not appear in the comic strip but is systematically developed in the Encyclopedia that follows it, designates a material representation of the collective imagination. It is thus considered as much a theoretical concept as a fictional entity.[37]

Authors Serge Lehman and Fabrice Colin have recreated an entire mythological cosmogony, using elements of interwar science fiction. Indeed, they set up a coherent narrative that aims to explain the appearance of supermen during the First World War, when soldiers were subjected to chemical gases and X-ray weapons.[21]

The discovery of radium at the end of the 19th century and its radioactive principle played a decisive role in the origin of superhuman powers. In the literature of the 1920s and 1930s, this material played a central role, being a veritable "miracle material".[28] The personality of Marie Curie, who won awards for her work on radium, is exploited to the full in the series, which presents her as the tutelary figure of French supermen. Indeed, many scenes take place at the Radium Institute she founded, described as an iconic location by Serge Lehman, in the same way as the Baxter Building is for the Fantastic Four.[1]

The presence of the couple Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie illustrates this ambivalence between, on the one hand, the "super-science" inherited from Marie Curie and, on the other, the "serious science" in the name of which Frédéric is conducting research into the atomic bomb.[28]

The theme of the superman, a central element in the series, refers as much to a long tradition of fantasy and anticipation storytelling, where European supermen, heirs to the justiciers-gentilshommes of the 19th century, flourished under the pen of the feuilletonistes,[9] as to the Nietzschean superman, to the point of quoting in the introduction and conclusion passages from Nietzsche's poem Ainsi parlait Zarathoustra, which deals with the superman.[8]

For Nietzsche the superman is above all a metaphor illustrating that, to transcend himself, man is called upon to free himself from idols and morality, and to voluntarily place himself "beyond good and evil". Then, once he has become aware of the relativity of values, he must become capable of accepting them, no longer by automatism, but by choice. The comic strip also illustrates the development of European supermen by showing Hitler's reinterpretation of the Nietzschean concept. He literally applies Nietzsche's words as a psychological program, as he breaks down all moral inhibitions to enjoy unrestrained freedom.[40]

Characters

[edit]The story offers a rewriting of history, with characters from interwar serial fiction taking shape alongside historical figures in Europe on the eve of the Second World War.[35]

Les Chimériques

[edit]

The Chimera Brigade, which gives its name to the series, is made up of four fantastic entities born of the brain of Jean Séverac, a French doctor wounded in the First World War.[19] The main story revolves around this quartet of supermen. George Spad's fake novel L'Homme chimérique, conceived as a preparatory work, served as the basis for the story, with the La Brigade chimérique series incorporating the narrative elements of this fake novel. In a commentary published as an appendix to the 2012 edition, Serge Lehman tells the story of Lieutenant Jean Brun de Séverac, a 25-year-old military doctor who arrives in the trenches in 1917. He fell in love with an English nurse, Patricia Owens, but she soon died of tuberculosis. In 1918, Séverac fell victim to a German attack while in his laboratory. When the gas cleared, his men discovered four individuals amid the rubble of his laboratory: a teenager, a giant with a beard and hair, a young woman resembling Patricia Owens and a bald, skeletally thin man,[2] who became entities with marvelous powers when the series was completed: the Unknown Soldier has angel wings and a great sword of flame; the Brown Baron is a humanoid bear of extraordinary strength; Patricia commands life forms; and Doctor Serum is a skeleton with a deadly touch. For fifteen years, the Chimeric Brigade travels the world fighting villains in adventures with recurring foe Dr. Mabuse,[41] at the end of which Marie Curie manages to reverse the quadripartition and awaken an amnesiac Jean Séverac. Taken care of by Irène Joliot-Curie, Séverac regains his memories and can use his ring to swap with the Chimeric at will. The latent presence of the Brigade, even in the surname Séverac, shows that these four members are really just concepts, archetypes linked to the Jungian collective unconscious. As such, they implicitly represent humanity's physical and moral potential.[42]

The Chimera Brigade is up against its German counterpart, described as "anti-being" and made up of Doctor Mabuse, the Blue Angel and Werewolf.[43] This group, Gang M, is led by Mabuse, a character who first appeared in 1921 in the novel Docteur Mabuse, le Joueur by Luxembourgish writer Norbert Jacques, then popularized by Fritz Lang's films of the 1920s and 1930s. Serge Lehman and Fabrice Colin make him the main villain of the story, the harbinger of Nazism.[44] This hypnotically powerful character illustrates the power of mental manipulation and, more generally, propaganda.[31] In his plan to destabilize Europe, he is accompanied by the Blue Angel, a tribute to Marlene Dietrich, who plays a dancer in Josef von Sternberga's film of the same name, and Werwolf, a lycanthrope inspired by the Nazis who, after the defeat of 1945, fought underground under the code name "werwolf".[8]

This Gang M, made up of a cold scientist, a female vampire and a "man-animal", is the equivalent of the Brigade's chimeric entities: Doctor Serum, Matricia and Baron Brun,[31] who are missing a member: the Unknown Soldier, who represents the moral figure. Indeed, the story reveals that Gang M, like the chimeric Brigade, was formed during trench warfare from an Austrian lieutenant, "L'Homme de Comines", who underwent the same quadripartition as Séverac. Behind this revelation lies Adolf Hitler, who himself suffered from gas poisoning after being poisoned by mustard gas on 13 October 1918 near Comines; the authors have incorporated this injury and the long convalescence that followed, into recita.[9] Hitler returns to human form at the end of the series, having amputated one of his own limbs, Ashaverus the Wandering Jew, thus depriving himself of his share of humanity, this entity playing the role of superego, like the Unknown Soldier for Séverac.[40]

The first is that this reference to Franz Kafka's hero provides a link between "popular literature" and "high literature", insofar as Serge Lehman considers The Metamorphosis to be one of the finest creations of twentieth-century literature;[1] the second is due to onomastic reasons. Unlike the French translation of The Metamorphosis, which refers to Gregor Samsa as "cockroach", Kafka's original version uses the word "ungeziefer", which should really be translated as "vermin", the same word Hitler uses to designate Jews.[20]

Other main characters

[edit]European supermen are at the heart of the series, which tells the story of how they came to be. The treatment of the Nyctalope in particular illustrates the disappearance of these superheroes from the collective memory. Léo Saint-Clair, a hero with a prestigious career but past glory, embodies the values of the Third Republic, and like it, is already a thing of the past in 1939. His conservative values and egocentricity make him appear as a cantankerous, backward-looking character whose career serves as a metaliterary discourse to illustrate the future of the genre literature he represents.[5] Founder of the Comité d'Informations et de Défense (CID), whose base is hidden beneath Montmartre, he was appointed by Marie Curie as her heir in July 1934, on condition that he protect Spain from the fascists. Wracked by the guilt of having betrayed this promise, the result is a hostile resentment towards his daughter, Irène Joliot-Curie, and her American allies.[38] At the end of the series, aware of his twilight fame, he reproaches his biographer Jean de La Hire for his literary mediocrity and his inability to produce a novel worthy of his adventures. Here, this discourse is universalized in the image of all soap opera heroes about to disappear from memory, unlike those who were fortunate enough to have talented creators, like Fantômas or Arsène Lupin, whose portraits adorn the Nyctalope's office.[45]

Under the patronage of Marie Curie, the tutelary figure of "superscience", researchers embody the scientific mystery that has always surrounded superheroes.[42] The Joliot-Curie couple, winners of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935 for their work on radioactivity, headed up the Radium Institute, charged with studying the extraordinary abilities of supermen. Under-Secretary of State for Research in 1936, Irène took over as head of the Radium Institute, not when her mother died in 1934 as the comic strip states, but in 1946. Moreover, after the war, she helped create the French Atomic Energy Commission (Commissariat à l'énergie atomique), of which her husband Frédéric was the first High Commissionera,[10] suggesting Frédéric Joliot-Curie's commitment to what he called "serious science", namely research into the atomic bomb.[28]

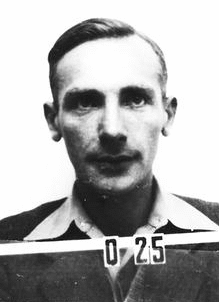

Finally, a writer, whose identity is shrouded in mystery, is at the center of the story. This boyish-looking woman calls herself "George Spad", a name reminiscent of George Sand. However, declaring herself to be using a collective pseudonym of which she is only the actual user, she is confused in the story with Renée Dunan.[22] Indeed, not only is George Spad presented as a feminist, an anarchist and, like her model Renée Dunan, close to André Breton and the early Surrealists, she also claims to be the author of Baal, une aventure de Palmyre. This novel refers to Renée Dunan's 1924 work Baal ou la magicienne passionnée, in which the protagonist is a magician named Palmyre.[46] In the course of the series, her past is revealed: fighting alongside the Partisan during the Spanish Civil War, she is exposed to a chemical cloud by the Phalange. Unable to return to combat, she fled to Paris in February 1937, where she was noticed by André Bretona. Her exposure to chemical gas causes her to hear voices, which she eventually understands to be the Hyperworld -which she calls her Invisible[31]- speaking directly to her. The authors use her fate as a metaphor for the demise of European fantasy literature, since after being arrested by the Germans and deported to the Auschwitz camp, she dies in the gas chambers, science definitively winning out over superscience.[31]

Secondary characters

[edit]

In addition to paying tribute to popular literature, the authors place the imaginary world of the interwar period at the heart of the story, which is why numerous historical and fictional characters from the 1920s and 1930s are present or referenced. First and foremost, novelists occupy a place of their own, acting as observers and archivists of the exploits of supermen.[20] Two groups of personalities from Parisian literary circles stand out. The first is the Club de l'Hypermonde, made up of a number of authors of fantasy literature. This fictitious company is presided over by Régis Messac in his capacity as founder of the first collection of science fiction books, "Les Hypermondes".[47] Under his presidency were Louis Boussenard, J.-H. Rosny aîné, Jean Ray, Jacques Spitz and the young René Barjavel.[38] The second group was made up of the Surrealists, among whom George Spad was for a time an important figure. Serge Lehman gives this artistic movement an important place, as many of its members had close ties with science fiction, such as Renée Dunan, Jacques Spitz, Boris Vian and René Daumal.[47] In addition to featuring the movement's theorist, André Breton, the authors took the liberty of extending the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme to January 1939[21] for the purposes of the story.

The very essence of the series' universe, called hyperworld by the authors, lies in its propensity to bring together numerous heroes from popular literature who appear as secondary characters or simply at the turn of a square. That's why Belgian writer Jean Ray's hero Harry Dickson finds himself chatting with British writer William Hope Hodgson's Thomas Carnacki, while the twins in J.- H. Rosny's twins converse with German Paul Alfred Müller's Atlantean Sun-Koh; Paul Féval Jr.'s Félifax, a member of Jean de La Hire's CID organization, is sent to investigate Fritz Lang's Metropolis; and heroes like Marcel Aymé's François Dutilleul and Jacques Spitz's Dr. Flohr, the scientist behind L'Homme élastique, frequent Marie Curie's Radium Institute.[21]

Summary

[edit]Told over twelve episodes, the story takes place over a year between 30 September 1938 and 30 September 1939.

Curie mechanoid

[edit]

In September 1938, at the invitation of Dr. Mabuse, supermen from all over Europe and the United States travel to Metropolis, a new town in the Austrian Alps, to discuss ways of preserving peace. Irène Joliot-Curie, smuggled in under cover by the Soviet organization We Others, witnesses Mabuse's proposal that the superhumans join forces to satiate humanity and establish their domination of the world. Her speech is interrupted, however, by the intervention of a shapeshifter, Gregor Samsa aka the Cockroach, who informs the audience of the German doctor's warmongering plans for Central Europe. His entrance provokes a pitched battle between Mabuse and his allies on the one hand, and an Atlantic front made up of English, American and French heroes on the other, who manage to get Samsa to safety.

The Passe-muraille's Last Mission

[edit]Six months later, the Nyctalope, head of the CID organization and protector of Paris since Marie Curie's death, chooses a new biographer in surrealist circles in the enigmatic George Spad. Meanwhile, at the Radium Institute, while Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie watch experiments aimed at creating an elastic man, the couple receive a missive from the "We Others" organization urging them to pass on Samsa's revelations. A friend of the couple, François Dutilleul agrees to break into the CID headquarters hidden beneath Montmartre, to request Samsa's revelations.

Cagliostro

[edit]The Nyctalope captures the Elastic Man, an escapee from the Radium Institute who is capable of altering his size. Eager to punish the Joliot-Curies for the Passe-Muraille's intrusion into his lair, the protector of Paris suggests that his prisoner take revenge on the couple responsible for his transformation. Meanwhile, in the course of his investigation into the transfer of power between Marie Curie and the Nyctalope, George Spad meets a close friend of the scientist, Dr. Jean Séverac. This veteran of the Great War declares himself incapable of informing her due to a sixteen-year coma, from which he emerged in 1934. In the meantime, the hypnotist Cagliostro appears before them to provoke a massacre, but the intervention of the witch Palmyre thwarts his murderous plans. Picking up Spad's file, Jean Séverac comes across a photo of the Chimeric Brigade, and recognizes the individuals who haunt his dreams.

La Chambre ardente

[edit]Troubled by George Spad's revelations about his links with a group of mysterious superheroes close to Marie Curie – known as the Chimeric Brigade – Jean Séverac goes to the Radium Institute. The Elastic Man's attack on the Institute leads to the appearance of the Four Chimeras. After their victory over the giant, the four individuals merge back into Jean Séverac. Meanwhile, the Nyctalope secretly turns to the Soviet organization We Others.

The Broken Man

[edit]Jean Séverac exposes himself to the chambre ardente, a device developed by Marie Curie, allowing him to access the Chimeric Brigade's memories during his "coma". As vampyres emerge from the sewers of Paris, the CID intervenes with Felifax to hunt them down. London is also under attack from unknown machines that bombard the inhabitants with hypnotic messages urging them to kill each other. Dr. Thomas Carnacki's magical powers prove insufficient, so John the Strange and his dog Sirius put an end to the threat before discovering the Nazi sigil adorning the robots' inner chests.

Happy birthday Doctor Séverac

[edit]

Xenobia, an extraterrestrial creature that has terrorized the City of Light in the past, manages to escape from the Radium Institute. Although intrinsically harmless, the creature nevertheless represents a real danger to Parisians, as it feeds on electricity, much to the delight of the Vampyres who are waiting to emerge on the surface, taking advantage of the darkness.

The Chimeric Brigade intervenes, but rather than confront the Xenobie, Matricia chooses to provide it with maximum energy by diverting all the electricity to the Eiffel Tower. Grateful, the alien creature is able to return home to space.

International politics

[edit]Irène has modified Jean Séverac's ring so that he can swap with the Chimeric without having to use the cumbersome chambre ardente. And while she asks him to investigate Gregor Samsa's captivity at the CID, the French government mandates Félifax to investigate German activities in Metropolis.

Before leaving on his mission, Séverac visits Spad, whom he finds unconscious, overcome by inner voices. Meanwhile, the Nyctalope and the Accelerator are in Moscow to negotiate an alliance with "We Others" against Mabuse, but the strategic meeting with Big Brother is repeatedly postponed.

HAV-Russian

[edit]In Moscow, the Nyctalope and the Accelerator realize they've been duped by "We Others", while in Metropolis, convinced by Mabuse's experiments on turning Jews into skull soldiers, Big Brother agrees to seal an alliance between the two countries.

In Paris, the Chimeric Brigade attacks CID headquarters to rescue Gregor Samsa. While the Brown Baron and Serum face a monster from the depths of time, the other members of the commando team are unable to prevent the death of Samsa, who utters a few enigmatic words before dying: "H-A-V-Russian".

The Hyperworld Club

[edit]To unravel the meaning of Samsa's last words, George Spad enlists the help of the Hyperworld Club, an association of serialists who are veritable archivists of superscience. She discovers that Gregor Samsa belonged to Gang M at the end of the war, under the name Ashaverus (H-A-V-russian). This gang, which formed a German chimeric brigade from the "Man of Comines", nevertheless expelled Ashaverus from its ranks after a few months.

Warned by Felifax of the alliance between "We Others" and Mabuse, the Chimeric Brigade decided to confront the latter directly in Metropolis.

TOLA

[edit]

Rejected by the Nyctalope, Irène Joliot-Curie nevertheless manages to find a means of transport to take the Chimeric Brigade to Metropolis. While Sévérac sets off for the German city, Spad heads for Warsaw in search of Tola, the wife of Irène's assistant, Joseph Rotblat. Having finally solved the mystery of her inner voices, she realizes that they are in fact emanations from the Hyperworld. However, on her way to find Rotblat's wife, the writer is confronted by the Elastic Man, back in Warsaw to take his revenge on men.

The head arrives

[edit]The Elastic Man attacks Spad, who has come to rescue Tola Rotblat. He is killed thanks to the intervention of Nazi soldiers, who nevertheless arrest the two women.

Meanwhile, in Metropolis, the Chimeric Brigade confronts Mabuse and his henchmen. With an advantage over Gang M, Mabuse turns the tables by pitting Serum against the Unknown Soldier. The brief fratricidal struggle that ensues is exploited by their adversaries, who kill all four Chimeric, thus putting an end to the last obstacle to their ill-fated project.

Epilogue: The Great Nocturne

[edit]Revealing the alliance between Germany and the USSR, Mabuse unleashes war against the European democracies by attacking Warsaw.

On the docks in London, escorted by Monsieur Steele, the European supermen board a ferry to flee to the United States. Exfiltrated from Prague, the Golem announces that his departure will bring about the eclipse of superscience in Europe for a long time to come.

In Paris, the lonely Nyctalope sinks into bitterness and madness, while in Metropolis, Gang M, realizing that superscience is waning before it dies out, sets about merging to reform the "Man of Comines" aka Adolf Hitler.

George Spad, having failed to save Tola, is taken to an extermination camp. She hears the voices of the Hyperworld again, telling her that he will disappear but return one day.

Commentary on European Sci-Fi

[edit]The series is in part based on Serge Lehman's initial questioning of the reasons for the disappearance of European superheroes after the Second World War in favor of an almost exclusively American science fiction. Within the series, Lehman provides some reasons as to why this occurred.

Cultural amnesia or the decline of the imagination

[edit]

To explain the disappearance of European supermen from the collective memory, Serge Lehman applies a psychoanalytical process[48] in which he draws a parallel with the comic book industry and their editorial motivations to intentionally make certain characters disappear periodically. Thus, he invents circumstances in fiction to explain the collapse and disappearance of European science fiction. First of all, supermen and proto-superheroes, which were a very important element of interwar European science fiction, were largely forgotten after the Second World War, as the concept was used extensively by the Nazi regime through the figure of the pure white superman. So, in the imagination, European supermen were compromised when they were reclaimed by the Nazis. This is why public opinion unconsciously preferred to forget them rather than face up to what they represented.[1] The example of the Nyctalope, the series' central character, is a perfect illustration of the fate of these proto-superheroes. Endowed with superpowers thanks to his night vision, and close to power as the protector of Paris, he maintains a wait-and-see role in the face of the German threat, foreshadowing, for authors Lehman and Colin, his passive role during the Occupation.[49] A very popular character in the first half of the 20th century, with numerous adventures recounted in nineteen novels, he was completely forgotten from the 1950s onwards.[50]

This recovery of the superman theme, and more generally the reinterpretation of concepts, is illustrated by Dr. Mabuse's manipulative projects. Claiming "the power to create reality through speech", Mabuse can literally transform human beings into animals or matter. Through the sacrifice of Jews, he builds the city of Metropolis in just a few months. At the end of the final battle between the Chimeric Brigade and Gang M, the Unknown Soldier is defeated and sacrificed in the name of Mabuse's new way of thinking. By becoming a winged figure sculpted on a building, the figure of the soldier from the French trenches is recuperated and reinterpreted by the enemy.[44] Here again, Mabuse's hypnosis, a metaphor for Nazi propaganda, acts as it did earlier when Cagliostro drove Parisians to kill each other, or when hypnotic robots did the same in London. Manipulated, Dr. Serum kills the Unknown Soldier – visualized as a cockroach – annihilating the Brigade in the process. While the Chimeric Brigade represents an idealized, overpowering France, and in fact physically dominates Gang M, it is on the strength of ideas that it loses the battle. Deprived of its leader, it withered away, like France itself: a defeated, divided, collaborationist country.[31]

The science-fiction literary genre came to an abrupt halt with the emergence of twentieth-century ideologies, as the imaginary gave way to political realism. A veritable complex prevented French authors from treating the genre seriously other than as a form of caricature and humor.[27] Nazism, embodied in the series by Gang M, worked hard to dissipate from European territory all hope and all trace of imagination, which are the two conditions for the appearance of superheroes. This is why, having taken care to standardize thought, Gang M – itself the product of imagination – no longer has a place in the world, and must give way to his alter ego, Adolf Hitler.[51] The establishment of the anti-being thus embodies the annihilation of a number of European values, including its humanism, its relationship with the imaginary and its ability to dream up its heroes to create a popular mythology.[31]

Passing the torch of the SF genre: from Europe to the United States

[edit]

By constantly blending fiction and politics, the series bears witness to Europe's failure to overcome its self-destructive tendencies, in the face of a United States where hope was shifting on the eve of the Second World War.[43] Moreover, for Lehman, the ability to express one's value system is a privilege of the victors, so the Americans – and to a lesser extent the British – had a monopoly on the superhero as a fictional figure from the 1950s onwards; while in Europe, due to the discredit caused by the Nazi takeover of the concept, the superhero was both mocked for its naiveté, and ideologically dubious.[1]

The authors equate the end of European supermen with the emergence of American superheroes. Indeed, this displacement of hope and imagination is illustrated by the exile of supermen from the European continent.[52] The Golem of Prague, for example, is also forced to move to the United States. This man of clay, fashioned by Rabbi Loew, not only evokes the Jewish people made undesirable in Europe, but, as the last survivor of the European Magic Age,[38] he is also the source of the superscientific powers that sustain the story's marvellous dimension; his departure therefore brings the uchronic parenthesis of history to an end.[35] His departure also serves as a metaphor for the brain drain of Europe's Jews during the 20th century,[53] whether scientifically, as in the case of Albert Einstein, or culturally, as in the case of the creators of the first comic-books, most of whom were of Jewish descent: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, Will Eisner, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster.[31] These are the same people who created American superheroes, who are ultimately very similar to European supermen. For example, while the Nyctalope can be seen as a sort of dark-sighted Nick Fury, heading up a French-style SHIELD, the witch Palmyra appears as a female counterpart to Doctor Strange, capable of being obeyed by monsters similar to those in Lovecraftian literature.[54]

This exile of European supermen is organized by Mr. Steele, easily recognizable as Clark Kent. This archetypal American superhero symbolizes in the series the new face of the superman since he has established himself in America.[31] Indeed, when the Golem arrives, he kneels before it calling it "father", and in fact claims to be its heir.[51]

Towards the return of European supermen?

[edit]

With supermen having fled, died or gone astray, like the Nyctalope gone mad, the European superheroic imaginary seems to have been sterilized. Nevertheless, the series concludes with the enlistment of new recruits, Frenchman Bob Morane and Englishman Francis Blake illustrating an adaptation of the imaginary.[36] This scene marks a transition in the European imagination between the superman and the adventurer, who becomes the new heroic figure of popular literature and comics. The other archetypal figure to flourish after the war, thanks in particular to the Gaullist myth, was the Resistance hero, who fought against fascism with derisory means. The Partisan character, also known in the series as "the hero without power", illustrates this new type of hero, staying on the docks in London to continue the fight in Europe.[31]

Moreover, the authors succeed in instilling hope for the future by laying the foundations for a possible resurgence of European supermen, not by creating an alternative model to American superheroes, but on the contrary by inscribing themselves in a Euro-American imaginary.[28] First and foremost, the Golem delivers a message of hope to Europeans. By declaring: "Win this war. Pay your debts", he suggests that Europe will once again become a leading power, and thus regain its ability to dream the world. What's more, the Hyperworld, in the voice of George Spad marching towards his tragic fate, is itself announcing its disappearance and future rebirth.[31] And finally, just as the authors open the series with a quotation from Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra, they conclude it with a phrase again taken from the poem: "And only when you have all denied me will I return among you" heralding the next return of the supermen. The final drawing depicts the Chambre ardente, Jean Séverac's lost ring in the Austrian Alps, seemingly awaiting the return of a new generation of European superheroes.[31]

Graphic style

[edit]The authors' work is both a tribute to the scientific marvelous and to old-fashioned anticipation, and born out of a desire to renew the superhero genre in France.

Graphic heritage

[edit]

The graphic work of illustrator Stéphane Gess and colorist Céline Bessoneau is in keeping with the tradition of popular literature, insofar as the authors aim to restore to their former glory European characters who have fallen into oblivion, unlike their American counterparts.[55]

La Brigade chimérique is teeming with visual details that demonstrate its affiliation with the marvelous-scientific genre.[56] The atmosphere recreated in the series adopts a retro, steampunk tone which, while it harks back to the pioneering science fiction of Jules Verne, is fully marked by the influence of the feuilletonistes and their taste for commercial excess, like the fantasies of a Gustave Le Rouge.[54] For example, one full-page illustration by draughtsman Stéphane Gess depicts a flying ship on which the Nyctalope lands by climbing out of a window. This drawing bears a strong resemblance to Albert Robida's 1902 lithograph La Sortie de l'Opéra en l'an 2000, with its similar aerial arrangements.[56]

In addition, to immerse readers as fully as possible in the story's literary imagination, the authors reproduced in the margin notes a number of covers from period series whose fictional characters or their writers appear in The Chimera Brigade, such as Belzébuth by Jean de La Hire, Le Réveil d'Atlantide by Paul Féval fils and H.-J. Magog, or Baal ou la magicienne passionnée by Renée Dunan. Gess also recreated the graphic environment by creating fake covers for fascicles that appear discreetly, such as Le merveilleux Baron Brun or Harry Dickson n°54 – La Mort qui marche (Harry Dickson n°54 – The Walking Death), which uses the graphic charter of Harry Dickson's adventures written by Jean Ray, adding an illustration and title that refer to Doctor Serum.[41]

Artistic choices

[edit]

Gess drew on a highly detailed script by Serge Lehman, a great connoisseur of Paris, to illustrate the 1930s in a fantasy Paris. While the historical characters were drawn from photographs, Gess had to make choices when designing the graphics for the fictional characters. He also diversified his influences. For the conception of the Blue Angel and Doctor Mabuse, he drew inspiration respectively from actress Marlene Dietrich and actor Rudolf Klein-Rogge, the heroes of Josef von Sternberg's and Fritz Lang's film versions, while for Le Passe-muraille, he departed from Jean Boyer's adaptation played by Bourvil, preferring a hero with the features of Jean-Pierre Cassel chosen for his elegance. For the characters who didn't have the honor of a film adaptation, Gess had to imagine them. On the subject of Nyctalope, for example, he declared: "I wanted a character who was very 'French', not a superhero at all".[3]

Halfway between the Franco-Belgian album and the American comic book, the series asserts this heritage between the two transatlantic cultures. To keep a steady pace, the story was divided into twelve episodes with a prologue and an epilogue, and published in six albums between August 2009 and October 2010. The authors thus opted for a hybrid format that adopts the form of the bookshop album and the narrative rhythm of American monthly comics.[57] In addition to the format, the series adopts the narrative codes of American comic books, i.e. a steady pace with twists and turns at the end of each episode, while instilling a European touch through the settings, characters and, above all, a European-centric plot.[54] This narrative breakdown, coupled with the graphic treatment, aimed to modernize the concept of European superheroes.[55]

Gess chose to use increasingly dark colors with each album cover, reflecting the evolution of the story, which ends on a very dark note. Influenced by the style of Mike Mignola, particularly in his Hellboy[3] series, Gess developed a clean, contrasting drawing style with a touch of Expressionism.[9] To create a steampunk atmosphere and aesthetic, he integrated period images with dreamlike mechanical constructions.[8]

Publication

[edit]The La Brigade chimérique saga was published by L'Atalante between August 2009 and October 2010. Scripted by Serge Lehman and Fabrice Colin, it is drawn by Gess and colored by Céline Bessoneau. The authors set out to publish six volumes, each comprising two stories, in the space of a year. The publication is a tribute to the soap operas that were in vogue at the beginning of the 20th century.[55]

Original collection

[edit]- Issue 1: Mécanoïde Curie – La Dernière Mission du Passe-muraille. L'Atalante. 2009. ISBN 978-2841724406. Script: Serge Lehman and Fabrice Colin - Drawing: Gess - Colors: Céline Bessoneau

- Issue 2: Cagliostro - La Chambre ardente. L'Atalante. 2009. ISBN 978-2841724741. Script: Serge Lehman and Fabrice Colin - Drawing: Gess - Colors: Céline Bessoneau

- Issue 3: L'Homme cassé - Bon anniversaire docteur Séverac. L'Atalante. 2009. ISBN 978-2841724758. Script: Serge Lehman and Fabrice Colin - Drawing: Gess - Colors: Céline Bessoneau

- Issue 4: Politique internationale - HAV-Russe. L'Atalante. 2010. ISBN 978-2841724963. Script: Serge Lehman and Fabrice Colin - Drawing: Gess - Colors: Céline Bessoneau

- Issue 5: Le Club de l'hypermonde - TOLA. L'Atalante. 2010. ISBN 978-2841725090. Script: Serge Lehman and Fabrice Colin - Drawing: Gess - Colors: Céline Bessoneau

- Issue 6: La tête arrive - Épilogue : Le Grand Nocturne. L'Atalante. 2010. ISBN 978-2841725236. Script: Serge Lehman and Fabrice Colin - Drawing: Gess - Colors: Céline Bessoneau

Complete

[edit]In 2012, L'Atalante published a single complete set of all six albums, with author's commentaries at the end of the volume presenting the preparatory work for the project, the sources of inspiration, a few graphic sketches, and explanations of the many literary and historical references scattered throughout the work.[58]

- La Brigade chimérique – L'intégrale. L'Atalante. 2012. ISBN 978-2841726189. Lehman and Fabrice Colin - Drawing: Gess - Colors: Céline Bessoneau

English-language publication

[edit]In April 2013, after meeting British publisher Titan Publishing at the London Book Fair, L'Atalante sold him the series.[59] It was translated into English and published by Titan from 2014 under the title The Chimera Brigade.

Reception

[edit]From the release of the first volume in August 2009, The Chimera Brigade made a real impact in the field of scientific marvelous comics.[60] It quickly became a cult hit with fans of this literary genre, which has been enjoying a revival since the beginning of the 21st century.[48]

Critical reception

[edit]Although the resemblance of La Brigade chimérique to its elder sibling, Alan Moore's League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, is regularly evoked, the comparison is systematically seen as inappropriate by critics, given the extent to which the two works differ, whether in terms of their intended purpose or the method employed.[4][54] In this respect, the aim of the series initiated by Serge Lehman to not only create a common genealogy with American superheroic mythology, but also to rethink historical events through the prism of the European imagination of the 1920s and 1930s, is deemed to have been successful.[4][31][52][61]

Unanimously recognized for its literary erudition,[48][62][54][61] the work manages to describe the complex geopolitical situation of Europe in the late 1930s, while maintaining a fluid, comprehensible narrative.[63] The series possesses several levels of reading, making it intelligent and subtle,[52] and requiring rereadings to grasp all its subtleties.[64][61] The frequent literary allusions have sometimes been perceived as a tendency towards "name dropping", with the criticism that secondary characters are not properly fleshed out,[48][62] a criticism that has been somewhat mitigated by the publication of the leaflet alongside the complete series, which explains the numerous literary references that punctuate the series.[48]

In terms of narrative progression, the story takes time to introduce the key elements of the universe, with the corollary, in the eyes of some critics, of a story that is genuinely slow to begin:[62] the first three volumes set the scene and describe the various major players in the plot, and it's not until the fourth volume that the story suddenly becomes more disturbing and establishes itself as a truly dark work.[65][31][52]

Although the series is interesting in that it brings many fictional characters who had their hour of glory at the beginning of the 20th century out of oblivion,[49] the most interesting and best-exploited character in the saga appears to be the Nyctalope, particularly in comparison with the other protagonists, who lack charisma.[64] Moreover, the risk taken by the authors in integrating the Holocaust into the story, reinterpreting it from a superscientific perspective, is hailed for its success in describing all its horror and atrocity.[31][52] Claiming its filiation with comic books, the series evolves at the pace of the revelations carefully prepared in previous volumes[64] and manages to conclude each story with effective cliffhangers.[31][48][65] However, unlike American superhero comics, although La Brigade chimérique is not exempt from superheroic battle scenes,[31] their treatment is deemed too minimalist and not spectacular enough, as in the final battle between the brigade and Gang M.[31][52]

Drawings and colors

[edit]Critics noticed Gess's inspiration for Mignola's work, and felt that his drawings fit in very well with Serge Lehman's comments.[4][52][61] While Gess's line may appear old-fashioned and outdated to the reader at first glance, his graphic work succeeds in reviving the retro style of the 1920s–1930s, which ultimately gives the saga a strong visual identity,[64] as in the flashback scenes, accomplished with colorist Céline Bessonneau, which he introduces with great creativity.[65]

In addition, Gess's graphic work evolved considerably during the course of the writing process,[3] so much so that his graphic quality was greatly enhanced,[31] culminating in an almost cinematic mise-en-scène.[62]

Awards

[edit]The Chimera Brigade has received two awards.

In 2010, the series was awarded the BdGest'Art jury prize, organized by the BD Gest' website, which wished to recognize both the initiative of the modest L'Atalante publishing house in bringing out such an ambitious series, and the series itself, which succeeds in brilliantly constructing a complete narrative on European superheroes during a troubled period.[66]

The following year, he was awarded the Grand prix de l'Imaginaire 2011 in the comics category at the Festival Étonnants Voyageurs in Saint-Malo.[67] This honorary prize is awarded by a jury of specialists in literatures of the imaginary.[68]

Posterity

[edit]The Chimera Brigade – encyclopedia and game

[edit]In November 2010, a derivative of the series was published by Sans-Détour[27] under the title La Brigade chimérique – l'encyclopédie et le jeu. This supplement to the series is in two parts: the first, encyclopedic in nature, aims to provide a deeper understanding of the world of The Chimera Brigade, and the second is a role-playing game set in this world.[69] The book is written by a collective of authors including Romain d'Huissier, Willy Favre, Laurent Devernay, Julien Heylbroek and Stéphane Treille,[69] while Gess and Willy Favre add a number of previously unpublished illustrations.[27]

The first encyclopedic part is an independent creation from the series, although Serge Lehman wrote the preface, suggested a few developments and reviewed the texts.[40] It explores and deepens the universe of The Chimera Brigade, describing the European geopolitical context, the urban planning of major European cities, and its scientific postulates, which revolve around the notions of Plasma and the Hyperworld.[27] It also includes detailed biographies of the series' protagonists, as well as characters created by the Encyclopédie authors, such as the "Tribun", who makes explicit reference to Léon Daudet.[20]

The second part is a role-playing game allowing players to embody supermen with extraordinary faculties in 1930s Paris.[27] This work is complemented by two other volumes, Aux confins du merveilleux-scientifique (2011) and La Grande Nuit (2012), also published by Sans-Détour. Last but not least, six issues of a fanzine called La Gazette du Surhomme, containing unpublished game scenarios and character sheets, were published between summer 2011 and autumn 2016; the first two issues featured two game designers, Romain d'Huissier and Willy Favre.

Derived series

[edit]

Following the release of La Brigade chimérique, Serge Lehman published a number of comic book series set more or less in the same universe. In 2012, for example, he indirectly followed up the original series with Masqué. Published in four volumes by Delcourt and drawn by Stéphane Créty, this series is set in Paris-metropole in the near future. The Second World War has obliterated the memory of pre-war French supermen, and the influence of the Situationists has replaced that of the Surrealists. This near-future, dominated by the tutelary shadow of Fantômas, features the return of European superheroes through the adventures of Optimum.[70]

In parallel with Masqué, Serge Lehman reunited with Gess to publish L'Homme truqué in 2013 with Editions L'Atalante. Conceived as a prequel to The Chimera Brigade,[71] this comic is a free adaptation of two stories by Maurice Renard, the novels Le Péril bleu (1911) and L'Homme truqué (1921). Set in 1919, Lehman portrays a World War I soldier who has acquired superhuman vision as a result of a medical experiment. Marie Curie et le Nyctalope bridges the gap to The Chimera Brigade series, whose members appear briefly at the end of volume.[72]

The following year, accompanied by illustrator Stéphane de Caneva, Lehman began publishing the Metropolis series, a disenchanted utopian alternative to The Chimera Brigade.[71] Published between 2014 and 2017 by Delcourt, this tetralogy explores a parallel continuum in which the First World War was averted. The plot is based on a police investigation in the heart of Metropolis, a city that symbolizes Franco-German reconciliation.[39]

Between 2015 and 2016, the Lehman-Gess tandem published L'Œil de la Nuit (The Eye of the Night) for Delcourt, a three-volume series recounting the first adventures of the young Nyctalope. Following the model initiated by The Chimera Brigade, this new series not only blends homage to the popular literature of the interwar period and contemporary comics, but also aims to update an entire scientific marvelous heritage.[39]

Finally, Serge Lehman reunites with illustrator Stéphane de Caneva and colorist Lou – with whom he had collaborated on Metropolis – to publish a sequel in January 2022 entitled The Chimera Brigade - Ultimate Renaissance, set after Masqué.[73]

Film adaptation project

[edit]In 2015, Fabrice Colin, the comic book's scriptwriter, mentioned a film adaptation project for which he and Serge Lehman would be screenwriters.[74]

In December 2017, L'Atalante publishing announced that French animation studio Sacrebleu Productions had bought the film adaptation rights to The Chimera Brigade,[75] the adaptation of which would be entrusted to Bastien Daret for a 6 × 52' format.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Serge Lehman : RADIUM UNLIMITED". www.parislike.com. Retrieved 2024-09-27.

- ^ a b c d e "Interview de Serge Lehman et Fabrice Colin, scénariste de la bande dessinée La Brigade chimérique | BoDoï, explorateur de bandes dessinées - Infos BD, comics, mangas" (in French). Retrieved 2024-09-27.

- ^ a b c d Tao, Eric (2010-10-31). "La Brigade Chimérique. Episode 4. Gess, l'entretien". EO (in French). Retrieved 2024-09-27.

- ^ a b c d e Bi (2009)

- ^ a b Hummel (2015, p. 6)

- ^ a b Vas-Deyres (2011, p. 10)

- ^ a b c Hummel (2015)

- ^ a b c d e Flux (2010)

- ^ a b c d e Martin (2012)

- ^ a b "Serge Lehman (Masqué) : « Les récits de super-héros sont une branche (...)". ActuaBD (in French). Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ Lanuque (2015, p. 359.)

- ^ Lanuque (2015, p. 364)

- ^ Fournier (2014, p. 217)

- ^ a b Lanuque (2018, p. 297)

- ^ Lanuque (2015, pp. 365–367)

- ^ Lanuque (2018, p. 287)

- ^ Fournier (2014, p. 218)

- ^ Lanuque (2015, p. 369)

- ^ a b Lanuque (2018, p. 290)

- ^ a b c d Vas-Deyres (2011)

- ^ a b c d Hummel (2015, p. 4)

- ^ a b Hummel (2015, p. 10)

- ^ a b Vas-Deyres (2011, p. 11)

- ^ Hummel (2015, p. 11)

- ^ Hummel (2015, p. 12)

- ^ "Esthète de mule | Redux online | L'Homme chimérique". esthetedemule.redux.online. Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ a b c d e f Farinaud (2011)

- ^ a b c d e ericflux (2010-10-26). "La Brigade Chimérique. Episode 3 : Questions à Serge Lehman". EO (in French). Retrieved 2024-09-27.

- ^ Vas-Deyres & Lehman (2011, p. 14)

- ^ a b Vas-Deyres (2011, p. 12)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t d'Huissier (2009)

- ^ Vas-Deyres & Lehman (2011, p. 15)

- ^ Bleitrach, Danielle; Gehrke, Richard (2015-08-14). Bertolt Brecht et Fritz Lang, le nazisme n'a jamais été éradiqué (in French). LettMotif. ISBN 978-2-36716-122-8.

- ^ Ferro, Marc (2005-01-20). Les Individus face aux crises du XXe siècle: L'Histoire anonyme (in French). Odile Jacob. ISBN 978-2-7381-9031-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Hummel (2015, p. 3)

- ^ a b Lainé 2013, « Néanmoins, la relève est assurée [...] la réapparition des super-héros). »

- ^ a b Vas-Deyres & Lehman (2011, p. 17)

- ^ a b c d Vas-Deyres (2011, p. 13)

- ^ a b c Lanuque (2018, p. 295)

- ^ a b c Vas-Deyres & Lehman (2011, p. 16)

- ^ a b Hummel (2015, p. 9)

- ^ a b Lainé 2013, « Dans ce série, trois types [...] potentiel physique et moral de l'humanité. ».

- ^ a b Lanuque (2018, p. 291)

- ^ a b Lainé 2013, « Le méchant de l'histoire [...] propices à l'espoir et à l'imagination. ».

- ^ Hummel (2015, p. 7)

- ^ Mundzik, Fabrice (2014-12-14). "Serge Lehman, Fabrice Colin & Gess "La Brigade chimérique" (L'Atalante – 2009)". Renée Dunan (in French). Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ a b Hummel (2015, p. 5)

- ^ a b c d e f Suply (2012)

- ^ a b Fournier (2014, p. 222)

- ^ Fournier (2014, p. 125)

- ^ a b Lainé 2013, « Le dernier segment de cette saga [...] de stériliser l'imaginaire. »

- ^ a b c d e f g L. (2010f)

- ^ Lainé 2013, « En cela, la Brigade chimérique [...] fuite des cerveaux vers d'autres pays. »

- ^ a b c d e d'Huissier (2009)

- ^ a b c "Gess nous entraîne dans les méandres obscurs des Contes de la (...)". ActuaBD (in French). Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ a b Hummel (2015, p. 8)

- ^ Lainé 2013, « L'ambition des auteurs [...] partagent un terreau commun. ».

- ^ Hummel (2015, p. 2)

- ^ "L'Atalante vend sa Brigade chimérique à l'éditeur Titan Publishing". ActuaLitté.com (in French). Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ Lanuque (2018, p. 289)

- ^ a b c d MAGNERON, Philippe. "Brigade Chimérique (La) 6. La Tête arrive - Le Grand Nocturne". www.bdgest.com (in French). Retrieved 2024-09-27.

- ^ a b c d L. (2010c)

- ^ L. (2010a)

- ^ a b c d L. (2010e)

- ^ a b c L. (2010b)

- ^ MAGNERON, Philippe. "BDGest'Arts 2010". www.bdgest.com (in French). Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ "Grand Prix de l'Imaginaire 2011 – Grand Prix de l'Imaginaire" (in French). Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ "Présentation – Grand Prix de l'Imaginaire" (in French). Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ a b Dasse (2010)

- ^ MAGNERON, Philippe. "Dossier Masqué – La nouvelle série de Créty et Lehman". www.bdgest.com (in French). Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ a b "Fiction Electrique: Serge Lehman et le pulp français". Fiction Electrique. 2016-07-25. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ "sur l'autre face du monde – Renard Maurice, Lehman Serge, Gess "L'homme truqué"". www.merveilleuxscientifique.fr (in French). Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ Addictic. "Un nouvel album pour la Brigade Chimérique". ActuSF (in French). Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ F. "au programme". (please follow) the golden path (in French). Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ "Un film pour la Brigade Chimérique - Elbakin.net". www.elbakin.net (in French). Retrieved 2024-03-01.

Bibliography

[edit]- Fournier, Xavier (2014). Super-héros. Une histoire française. Paris: Huginn & Muninn. ISBN 978-2-36480-127-1.

- Lainé, Jean-Marc (2013). Super-héros ! : La puissance des masques. ISBN 978-2-36183-109-7.

- Lanuque, Jean-Guillaume (2015). Le retour du refoulé ? Sur le renouveau du merveilleux scientifique. Encino (Calif.): Black Coat Press. ISBN 978-1-61227-438-6.

- Lanuque, Jean-Guillaume (2018). La bande-dessinée, avenir du merveilleux-scientifique ?. Encino (Calif.): Black Coat Press. ISBN 978-1-61227-749-3.

- Bi, Jessie (2009). a Brigade Chimérique (t.1 & 2).

- Dasse, Christophe (2010). Jeu de rôle La Brigade Chimérique : L'encyclopédie.

- d'Huissier, Romain (2009). Actualité diverse de Romain d'Huissier.

- Farinaud, Stéphane (2011). La brigade Chimérique L'Encyclopédie.

- Flux, Éric (2010). La brigade chimérique. Épisode 1 : les sources.

- Flux, Éric (2010). La brigade chimérique. Épisode 2 : la chute.

- Hummel, Clément (2015). "Pour un imaginaire (mythique) de la fiction de genre d'avant-guerre, La Brigade chimérique (2009–2010) de Serge Lehman". Journée d'étude doctorale « Genres littéraires et fictions médiatiques ».

- La Brigade chimérique (2009–2013).

- L., Vincent (2010a). "Du comics à la française..." SciFi-Universe.

- L., Vincent (2010b). "Les éléments sont patiemment posés..." SciFi-Universe.

- L., Vincent (2010c). "L'intrigue s'enlise…". SciFi-Universe.

- L., Vincent (2010d). "Les choses sérieuses commencent maintenant..." SciFi-Universe.

- L., Vincent (2010e). "La fin est proche…". SciFi-Universe.

- L., Vincent (2010f). "Un épilogue convaincant, mais trop rapide…". SciFi-Universe.

- Lorenz, Désirée (2016). Modalités et enjeux de la réappropriation culturelle de la figure du super-héros dans La Brigade chimérique et Masqué de Serge Lehman. Infolio. pp. 151–171. ISBN 978-2-88474-824-7.

- Martin, Jean-Philippe (2012). La brigade chimérique, l'intégrale.

- Suply, Laurent (2012). La Brigade Chimérique : épitaphe des héros européens.

- Vas-Deyres, Natacha; Lehman, Serge (2011). Histoire(s) tentaculaire(s).

- Vas-Deyres, Natacha (2011). "La Brigade chimérique et son Encyclopédie". Quinzinzinzili, l'Univers Messacquien (12): 10–13.