Taxine alkaloids

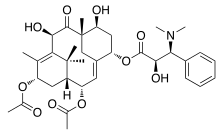

Taxine A

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2α,13α-Diacetoxy-7β,10β-dihydroxy-9-oxo-2(3→20)-abeotaxa-4(20),11-dien-5α-yl (2R,3S)-3-(dimethylamino)-2-hydroxy-3-phenylpropanoate

| |

| Other names

(1R,2S,3E,5S,7S,8S,10R,13S)-2,13-Diacetoxy-7,10-dihydroxy-8,12,15,15-tetramethyl-9-oxotricyclo[9.3.1.14,8]hexadeca-3,11-dien-5-yl (2R,3S)-3-(dimethylamino)-2-hydroxy-3-phenylpropanoate

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C35H47NO10 | |

| Molar mass | 641.751 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 204-206 °C[1] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

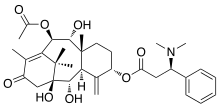

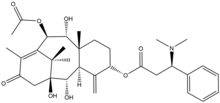

Taxine B

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

10β-Acetoxy-1,2α,9α-trihydroxy-13-oxotaxa-4(20),11-dien-5α-yl (3R)-3-(dimethylamino)-3-phenylpropanoate

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C33H45NO8 | |

| Molar mass | 583.722 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 115 °C |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Taxine alkaloids, which are often named under the collective title of taxines, are the toxic chemicals that can be isolated from the yew tree.[2][3] The amount of taxine alkaloids depends on the species of yew, with Taxus baccata and Taxus cuspidata containing the most.[4] The major taxine alkaloids are taxine A and taxine B although there are at least 10 different alkaloids.[5] Until 1956, it was believed that all the taxine alkaloids were one single compound named taxine.[4]

The taxine alkaloids are cardiotoxins with taxine B being the most active.[6] Taxine alkaloids have no medical uses but Paclitaxel and other taxanes that can be isolated from yews have been used as chemotherapy drugs.[7]

Provenance

[edit]

Taxine can be found in Taxus species: Taxus cuspidata, T. baccata (English yew), Taxus x media, Taxus canadensis, Taxus floridana, and Taxus brevifolia (Pacific or western yew). All of these species contain taxine in every part of the plant except in the aril,[citation needed] the fleshy covering of the seeds (berries). Concentrations vary between species, leading to varying toxicities within the genus. This is the case of Taxus brevifolia (Pacific yew) and Taxus baccata (English yew); T. baccata contains high taxine concentrations, which leads to a high toxicity, whereas T. brevifolia has a low toxicity. There are seasonal changes in the concentrations of taxine in yew plants, with the highest concentrations during the winter, and the lowest in the summer.[8] The poison remains dangerous in dead plant matter.[9]

These species have distinctive leaves, which are needle-like, small, spirally arranged but twisted so they are two-ranked, and linear-lanceolate. They are also characterized by their ability to regenerate from stumps and roots.[8]

Taxus species are found exclusively in temperate zones of the northern hemisphere.[10] In particular T. baccata is found all over Europe, as a dominant species or growing under partial canopies of deciduous trees. It grows well in steep rocky areas on calcareous substrates such as in the chalk downs of England, and in more continental climates it fares better in mixed forests. T. baccata is sensitive to frost, limiting its northern Scandinavian distribution.[11]

History

[edit]The toxic nature of yew trees has been known for millennia.[12] Greek and Roman writers have recorded examples of poisonings, including Julius Caesar's account of Cativolcus, king of Eburones, who committed suicide using the “juice of the yew”.[13] The first attempt to extract the poisonous substance in the yew tree was in 1828 by Piero Peretti, who isolated a bitter substance.[14] In 1856, H. Lucas, a pharmacist in Arnstadt, prepared a white alkaloid powder from the foliage of Taxus baccata L. which he named taxine.[15] The crystalline form of the substance was isolated in 1876 by W. Marmé, a French chemist. A. Hilger and F. Brande used elemental combustion analysis in 1890 to suggest the first molecular formula of .[4]

For the next 60 years, it was generally accepted that taxine was made of a single compound and it was well known enough for Agatha Christie to use it as a poison in A Pocket Full of Rye (1953). However, in 1956, Graf and Boeddeker discovered that taxine was actually a complex mixture of alkaloids rather than a single alkaloid.[16] Using electrophoresis, they were able to isolate the two major components, taxine A and taxine B. taxine A was the fastest moving band and accounted for 1.3% of the alkaloid mixture, while taxine B was the slowest moving band and accounted for 30% of the mixture.[17] The full structure of taxine A was reported in 1982,[1] taxine B in 1991.[18]

Toxicity in humans

[edit]

Almost all parts of Taxus baccata, perhaps the best-known Taxus species, contain taxines.[19]

Taxines are cardiotoxic calcium and sodium channel antagonists.[20] If any leaves or seeds of the plant are ingested, urgent medical attention is recommended as well as observation for at least 6 hours after the point of ingestion.[21][22] There are currently no known antidotes for yew poisoning, but drugs such as atropine have been used to treat the symptoms.[23] Taxine B, the most common alkaloid in Taxus species, is also the most cardiotoxic taxine, followed by taxine A.[6][24][4]

Taxine alkaloids are absorbed quickly from the intestine and in high enough quantities can cause death due to general cardiac failure, cardiac arrest or respiratory failure.[25] Taxines are also absorbed efficiently via the skin and Taxus species should thus be handled with care and preferably with gloves.[26] Taxus Baccata leaves contain approximately 5 mg of Taxines per 1g of leaves.[24] The estimated lethal dose (LDmin) of taxine alkaloids is approximately 3.0 mg/kg body weight for humans.[27][28] Different studies show different toxicities; a major reason is the difficulty of measuring taxine alkaloids.[29]

Minimum lethal doses (oral LDmin) for many different animals have been tested:[29]

- Chicken 82.5 mg/kg

- Cow 10.0 mg/kg

- Dog 11.5 mg/kg

- Goat 60.0 mg/kg

- Horse 1.0–2.0 mg/kg

- Pig 3.5 mg/kg

- Sheep 12.5 mg/kg

Several studies[30] have found taxine LD50 values under 20 mg/kg in mice and rats.

Clinical signs

[edit]Cardiac and cardiovascular effects:

- Arrhythmia – Irregular heartbeats leading to lower cardiac output; itself a very severe symptom. Ventricular arrhythmias can lead to circulatory collapse (via cardiac arrest) very quickly if not treated.

- Bradycardia – Fewer heart beats per time unit.

Both these effects lead to hypotension, which gives many symptoms including:

and many other typical signs of low blood pressure.

Intestinal effects:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhoea

- Abdominal pain

Respiratory effects:

- Respiratory distress – Shortness of breath.

If the poisoning is severe and not treated:

- Loss of consciousness – Lack of oxygen due to low blood pressure and respiratory distress forces the body to shut down all but the most vital functions.

- Respiratory failure – Breathing stops.

- Circulatory collapse – Blood pressure drops to the point that not even the most basic functions can be sustained.

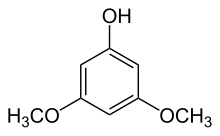

Diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosis of yew poisoning is very important if the patient is not already aware of having ingested parts of the yew tree. The method of diagnosis is the determination of 3,5-dimethoxyphenol, a product of the hydrolysis of the glycosidic bond in taxine, in the blood, the gastric contents, the urine, and the tissues of the patient. This analysis can be done by gas or liquid chromatography and also by mass spectroscopy.

Treatment

[edit]There are no specific antidotes for taxine, so patients can only receive treatment for their symptoms.

It is also important to control blood pressure and heart rate to treat the heart problems. Atropine has been used successfully in humans to treat bradycardias and arrhythmias caused by taxine. It is more effective if administered early, but it is also necessary to be cautious with administration because it can produce an increase in myocardial oxygen demand and potentiate myocardial hypoxia and dysfunction. An artificial cardiac pacemaker can also be installed to control the heartbeat.

Other treatments are useful to treat the other symptoms of poisoning: positive pressure ventilation if respiratory distress is present, fluid therapy to support blood pressure and maintain hydration and renal function, and gastrointestinal protectants. It may also be necessary to control aggressive behaviour and convulsions with tranquilizers.[34]

Prevention

[edit]The toxic effects of T. baccata have been known since ancient times. In most cases, poisoning is accidental, especially in cases involving children or animals. However, there are cases in which the poison is used as a suicide method.[35]

Because taxine poisoning is often only diagnosed after the death of the patient due to its rapid effect, preventing exposure is very important. Even dried parts of the plant are toxic because they still contain taxine molecules. Pet owners must ensure that yew branches or leaves are not used as toys for dogs or as perches for domestic birds.

Toxicity in animals

[edit]The effects of Taxine in humans are very similar to the effects on other animals. It has the same mechanisms of action, and most of the times the ingestion of yew material is diagnosed with the death of the animal. Moreover, clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention are mostly the same as in humans. This was seen due to the many experiments realized on rats, pigs, and other animals.[8]

Poisoning is typically caused by ingestion of decorative yew shrubs or trimmings thereof. In animals the only sign is often sudden death. Diagnosis is based on knowledge of exposure and foliage found in the digestive tract. With smaller doses, animals display uneasiness, trembling, dyspnea, staggering, weakness, and diarrhea. Cardiac arrhythmias worsen over time, eventually causing death. "Necropsy findings are unremarkable and nonspecific", generally including pulmonary, hepatic, and splenic congestion. With lower doses, mild inflammation may be seen in the upper gastrointestinal tract.[19]

Some animals are immune to the effects of taxine, particularly deer.[19]

Mechanism of action

[edit]The toxicity of the yew plant is due to a number of substances, the principal ones being toxic alkaloids (taxine B, paclitaxel, isotaxine B, taxine A), glycosides (taxicatine) and taxane derivates (taxol A, taxol B).[36]

There have been many studies about the toxicity of the taxine alkaloids,[37][38] and they have shown that their mechanism of action is interference with the sodium and calcium channels of myocardial cells, increasing the cytoplasmic calcium concentrations. Their mechanism is similar to drugs such as verapamil, although taxines are more cardioselective.[39] They also reduce the rate of the depolarization of the action potential in a dose-dependent manner. This produces bradycardia, hypotension, depressed myocardial contractility, conduction delay, arrhythmias, and other complications.[40]

Some taxine alkaloids have been isolated to study their effects and characteristics. This has allowed the discovery of some of the particular effects of each substance of the plant. For example, taxine A does not influence blood pressure, taxol causes cardiac disturbances in some people, that taxine B is the most toxic of these substances.[41]

Because a derivative from the yew, paclitaxel, functions as an anticancer drug, there have been investigations to show whether taxine B could also be used as a pharmaceutical.[42]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Graf, Engelbert; Kirfel, Armin; Wolff, Gerd-Joachim; Breitmaier, Eberhard (1982-02-10). "Die Aufklärung von Taxin A ausTaxus baccata L.". Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 1982 (2): 376–381. doi:10.1002/jlac.198219820222. ISSN 0170-2041.

- ^ Veterinary toxicology : basic and clinical principles. Gupta, Ramesh C. (Ramesh Chandra), 1949- (2nd ed.). Oxford: Academic. 2012. ISBN 9780123859266. OCLC 778786624.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Miller, Roger W. (July 1980). "A Brief Survey of Taxus Alkaloids and Other Taxane Derivatives". Journal of Natural Products. 43 (4): 425–437. doi:10.1021/np50010a001. ISSN 0163-3864.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Christina R.; Sauer, John-Michael; Hooser, Stephen B. (2001). "Taxines: a review of the mechanism and toxicity of yew (Taxus spp.) alkaloids". Toxicon. 39 (2–3): 175–185. doi:10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00146-x. ISSN 0041-0101. PMID 10978734.

- ^ Constable, Peter D (2016-10-25). Veterinary medicine : a textbook of the diseases of cattle, horses, sheep, pigs and goats. Hinchcliff, Kenneth W. (Kenneth William), 1956-, Done, Stanley H.,, Grünberg, Walter,, Preceded by: Radostits, O. M. (11th ed.). St. Louis, Mo. ISBN 9780702070587. OCLC 962414947.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Alloatti, G.; Penna, C.; Levi, R. C.; Gallo, M. P.; Appendino, G.; Fenoglio, I. (1996). "Effects of yew alkaloids and related compounds on guinea-pig isolated perfused heart and papillary muscle". Life Sciences. 58 (10): 845–854. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(96)00018-5. ISSN 0024-3205. PMID 8602118.

- ^ Muriel, Le Roux (2016-11-26). Navelbine® and Taxotère® : histories of sciences. Gueritte, Françoise. London. ISBN 9780081011379. OCLC 964620092.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-08. Retrieved 2016-10-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Robertson, John (2018). "Taxus baccata, yew". THE POISON GARDEN. Archived from the original on 2019-11-16.

- ^ Vanhaelen, Maurice; Duchateau, Jean; Vanhaelen-Fastré, Renée; Jaziri, Mondher (January 2002). "Taxanes in Taxus baccata Pollen: Cardiotoxicity and/or Allergenicity?". Planta Medica. 68 (1): 36–40. doi:10.1055/s-2002-19865. ISSN 0032-0943. PMID 11842324. S2CID 260283336.

- ^ Farjon, A. (2017) [errata version of 2013 assessment]. "Taxus baccata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T42546A117052436. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42546A2986660.en. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ F.), Roberts, M. F. (Margaret (1998). Alkaloids : Biochemistry, Ecology, and Medicinal Applications. Wink, Michael. Boston, MA: Springer US. ISBN 9781475729054. OCLC 851770197.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Julius., Caesar (1982). "31". De bello Gallico VI. Kennedy, E. C. (Eberhard Christopher). Bristol: Bristol Classical Press, Dept. of Classics, University of Bristol. ISBN 978-0862920883. OCLC 12217646.

- ^ Appendino, Giovanni (1996). Alkaloids: Chemical and Biological Perspectives. Vol. 11. Elsevier. pp. 237–268. doi:10.1016/s0735-8210(96)80006-9. ISBN 9780080427973.

- ^ Lucas, H. (1856). "Ueber ein in den Blättern von Taxus baccata L. enthaltenes Alkaloid (das Taxin)". Archiv der Pharmazie. 135 (2): 145–149. doi:10.1002/ardp.18561350203. ISSN 0365-6233. S2CID 84660890.

- ^ Graf, E (1956-04-07). "Zur chemie des taxins". Angewandte Chemie (in German). 68 (7): 249–250. doi:10.1002/ange.19560680709. ISSN 0044-8249.

- ^ Wilson, Christina R.; Hooser, Stephen B. (2007). Veterinary Toxicology. Elsevier. pp. 929–935. doi:10.1016/b978-012370467-2/50171-1. ISBN 9780123704672.

- ^ Ettouati, L.; Ahond, A.; Poupat, C.; Potier, P. (September 1991). "Révision Structurale de la Taxine B, Alcaloïde Majoritaire des Feuilles de l'If d'Europe, Taxus baccata". Journal of Natural Products. 54 (5): 1455–1458. doi:10.1021/np50077a044. ISSN 0163-3864.

- ^ a b c Garland, Tam; Barr, A. Catherine (1998). Toxic plants and other natural toxicants. International Symposium on Poisonous Plants (5th : 1997 : Texas). Wallingford, England: CAB International. ISBN 0851992633. OCLC 39013798.

- ^ Alloatti, G.; Penna, C.; Levi, R.C.; Gallo, M.P.; Appendino, G.; Fenoglio, I. (1996). "Effects of yew alkaloids and related compounds on guinea-pig isolated perfused heart and papillary muscle". Life Sciences. 58 (10): 845–854. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(96)00018-5. ISSN 0024-3205. PMID 8602118.

- ^ "TOXBASE - National Poisons Information Service". Archived from the original on 2020-11-20. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- ^ "Taxus baccata - L." Plants for a Future. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ Wilson, Christina R.; Hooser, Stephen B. (2018). Veterinary Toxicology. Elsevier. pp. 947–954. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-811410-0.00066-0. ISBN 9780128114100.

- ^ a b Smythies, J.R.; Benington, F.; Morin, R.D.; Al-Zahid, G.; Schoepfle, G. (1975). "The action of the alkaloids from yew (Taxus baccata) on the action potential in the Xenopus medullated axon". Experientia. 31 (3): 337–338. doi:10.1007/bf01922572. PMID 1116544. S2CID 8927297.

- ^ Fuller, Thomas C.; McClintock, Elizabeth M. (1986). Poisonous plants of California. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520055683. OCLC 13009854.

- ^ Mitchell, A. F. (1972). Conifers in the British Isles. Forestry Commission Booklet 33.

- ^ Watt, J.M.; Breyer-Brandwijk, M.G. (1962). Taxaceae. In The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa. Edinburgh, UK: Livingston. pp. 1019–1022.

- ^ Kobusiak-Prokopowicz, Małgorzata (2016). "A suicide attempt by intoxication with Taxus baccata leaves and ultra-fast liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry, analysis of patient serum and different plant samples: case report". BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 17 (1): 41. doi:10.1186/s40360-016-0078-5. PMC 5006531. PMID 27577698.

- ^ a b Clarke, E.G.C.; Clarke, M.L. (1988). "Poisonous plants, Taxaceae". In Humphreys, David John (ed.). Veterinary Toxicology (3rd ed.). London: Baillière, Tindall & Cassell. pp. 276–277. ISBN 9780702012495.

- ^ TAXINE – National Library of Medicine HSDB Database, section "Animal Toxicity Studies"

- ^ "Taxine". Toxnet.

- ^ "Yew poisoning". MedlinePlus.

- ^ "PLANT POISONING, CERVID - USA: (ALASKA) ORNAMENTAL TREE, MOOSE". ProMED-mail. 22 February 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ R.B. Cope (September 2005). "The dangers of yew ingestion" (PDF). Veterinary Medicine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-08. Retrieved 2016-10-14.

- ^ "Suicidal poisoning by ingestion of Taxus Baccata leaves. Case report and literature review" (PDF). Romanian Journal of Legal Medicine. XXI (2(2013)).

- ^ Ramachandran, Dr. Sundaram (2014). Heart and Toxins. Elsevier Science. p. 160. ISBN 9780124165953.

- ^ "Taxine- Mechanism of action". PubChem.

- ^ Tekol Y (1985). "Negative chronotropic and atrioventricular blocking effects of taxine on isolated frog heart and its acute toxicity in mice". Planta Medica. 51 (5): 357–60. doi:10.1055/s-2007-969519. PMID 17342582. S2CID 33600321.

- ^ Tekol Y; Göğüsten B (1999). "Comparative determination of the cardioselectivity of taxine and verapamil in the isolated aorta, atrium and jejunum preparations of rabbits". Arzneimittelforschung. 49 (8): 673–8. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1300481. PMID 10483513. S2CID 13312331.

- ^ G. Barceloux, Donald (2008). Medical Toxicology of Natural Substances: Foods, Fungi, Medicinal Herbs, Plants, and Venomous Animals. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 900. ISBN 9780471727613.

- ^ Suffness, Matthew (1995). Taxol: Science and Applications. p. 311.

- ^ Barbara Andersen, Karina (2009). "Future perspectives of the role of Taxines derived from the Yew (Taxus baccata) in research and therapy". Journal of Pre-Clinical and Clinical Research. 3 (1).

Further reading

[edit][1] Archived 2014-05-09 at the Wayback Machine Asheesh K. Tiwary, Birgit Puschner, Hailu Kinde, Elizabeth R. Tor (2005). "Diagnosis of Taxus (Yew) poisoning in a horse". Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation.

[2]Andrea Persico, Giuseppe Bacis, Francesca Uberti, Claudia Panzeri, Chiara Di Lorenzo, Enzo Moro, and Patrizia Restani (2011). "Identification of Taxine Derivatives in Biological Fluids from a Patient after Attempted Suicide by Ingestion of Yew (Taxus baccata) Leaves". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. Vol. 35