Tatannuaq

Tatannuaq | |

|---|---|

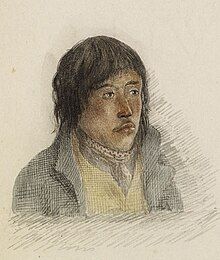

Sketch of Tatannuaq in 1821 | |

| Born | c. 1795 |

| Died | February or early March 1834 (aged 38–39) near Fort Resolution, North-Western Territory, British North America |

| Other names | Augustus |

| Children | 3 |

Tatannuaq (Inuktitut: ᑕᑕᓐᓄᐊᖅ, Inuktitut pronunciation: [tatanːuaq]; c. 1795 – early 1834), also known as Tattannoeuck or Augustus, was an Inuit interpreter for two of John Franklin's Arctic expeditions. Originally from an Inuit band 200 miles (320 km) north of Churchill, Rupert's Land, he found employment as an interpreter at the Hudson's Bay Company trading post in Churchill, becoming proficient in English and Cree.

Following a significant delay due to staying with family away from Churchill, he was hired as one of two Inuit interpreters accompanying John Franklin's disastrous 1819–1822 Coppermine expedition, plagued by starvation and the death of the majority of the expedition party on the return journey. He accompanied Franklin on the 1825–1827 Mackenzie River expedition, where he served a diplomatic role and dissuaded Inuit attacks on the expedition. After several years of interpreter service at the Hudson's Bay Company post at Fort Chimo, he departed to the interior in an attempt to assist in locating John Ross's expedition, but perished in bad weather a short distance outside Fort Resolution in early 1834.

Early life

[edit]Tatannuaq was born to an Inuit family in the 1790s, about 200 miles (320 km) north of Churchill in what is now the Kivalliq Region of Nunavut, then part of the loosely administered Rupert's Land territory. His name loosely translates to "the belly" or "it is full" in Inuktitut.[1][2] He had at least one brother.[3] His tribe regularly traveled by sleigh to Churchill in the spring, but wintered along the Hudson Bay coast in igloos, traveling inland in the summer to hunt reindeer and muskoxen. Prior to the spring thaws, they would hunt seal along the coast. Although his tribe would frequently trade with other Inuit groups further north, Tatannuaq stated that before his interpreter service he had only been as far north as Marble Island, in the vicinity of Rankin Inlet, around 275 miles (440 km) north of Churchill.[4][5][6]

In 1812, he was hired to work at the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) trading post at Churchill. Learning English and Cree, he began work as an interpreter for the company, where he assumed the English name of Augustus.[7][2] He was described by European explorers as a proficient writer, and would frequently write as a hobby.[8] Leaving the post briefly in 1814, he returned to work for the winter of 1815, then returned to Inuit lands the following year. In 1818, he married a woman of unknown name. The couple had three sons.[3]

Coppermine expedition

[edit]

Following the Napoleonic Wars, the British Admiralty placed great emphasis on the discovery of a hypothetical Northwest Passage, supposedly offering a viable sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Following an abortive 1818 expedition to Svalbard, Royal Navy officer John Franklin was appointed to travel overland from the North American mainland to explore the Arctic coastline, hoping to meet with a concurrent naval expedition by William Edward Parry intending to traverse Lancaster Sound.[9][10]

Franklin attempted to hire one or two Inuit interpreters for the expedition, but encountered difficulties and delays due to a lack of suitable candidates at Churchill or Cumberland House. A clerk at York Factory, tasked to hire interpreters, wrote in December 1819 that it would not be possible to find a suitable guide in time for the expedition's departure from its wintering grounds at Fort Enterprise the following year.[11] Franklin's party gathered at the North West Company (NWC) post of Fort Providence in early August 1820 and met with Akaitcho, chief of the Yellowknives, who warned of possible Inuit hostilities during the journey.[12]

Coppermine service

[edit]Tatannuaq, still in Inuit territory, was eventually contacted and hired as an interpreter for the expedition. On June 30, 1820, alongside another Inuit interpreter named Hoeootoerock, he arrived at York Factory. The two arrived at Norway House by August 14, reaching Cumberland House nine days later. From Cumberland House, they joined a large party departing towards Fort Chipewyan.[11] Departing from the fort on October 1 alongside a fur brigade headed to Fort Resolution,[13] they reached the Great Slave Lake a week later. Although Hudson's Bay Company trader Robert McVicar attempted to negotiate the interpreters' passage to Fort Providence aboard a NWC canoe, the vessel was unable to take additional weight, and the interpreters were forced to camp amidst winter weather by the HBC post at Moose Deer Island, near Fort Resolution. The two built an igloo on the island, and in December were found by NWC representative Willard Wentzel and fellow interpreter Pierre St. Germain, who escorted them to the expedition. They arrived at Franklin's post at Fort Enterprise on January 25.[14][15]

Upon arriving at Fort Enterprise, Franklin attempted to discern the abilities of the two interpreters by comparing their speech to a Inuttitut gospel. Presented with regional maps, Tatannuaq was able to recognize geographical features he had not visited, such as Chesterfield Inlet, and described various Inuit bands. Tatannuaq explained igloo construction to Franklin, who detailed the process meticulously in his diaries. Both Tatannuaq and Hoeootoerock came to be regarded as helpful and good-spirited interpreters by the expedition party.[6]

Franklin's party, departing from Fort Enterprise in June 1821, was the first British mission to descend the Coppermine River since Samuel Hearne's expedition in the early 1770s, which had allegedly led to the mass killing of Inuit at Bloody Falls. Reaching the falls on June 13th, 1821, Tatannuaq and Hoeootoerock were sent ahead of the party to attempt contact with local tribes. The two briefly made contact with a group of Inuit camped along the river, but the news of a visiting British expedition prompted the group to flee the area. After informing Franklin of the presence of local Inuit, Tatannuaq set out again the following day to meet with them. A brief encounter with a small group kayaking along the river was interrupted by arrival of Franklin and the Yellowknife scouts, causing the Inuit to once again flee.[3][16]

Tatannuaq and Hoeooterock again set out, crossing the river and encountering an elderly Inuk man named Terregannoeuck or White Fox, who at first attempted to fight the interpreters. Tattannuaq was able to calm the man, who talked with Franklin's party after receiving various gifts. Delighted by news that Akaitcho's Yellowknives wish to make peace with the Inuit, he agreed to meet with Akaitcho. Although Akaitcho was also able to calm an agitated Terregannoeuck, nothing came of their meeting. Tatannuaq returned the following day with gifts for Terragannoeuck and his wife, attempting to learn the local geography, but received little information. Terragannoeuck offered one of his daughters as a wife to Tatannuaq, who declined.[17][18]

The party advanced to the mouth of the river and turned east. From July to August, they charted 675 miles (1,086 km) of the Arctic coastline, but were forced to halt at Point Turnagain on Kiillinnguyaq on August 18.[3][19]

Return

[edit]

The return journey to Fort Enterprise saw the death of the majority of the expedition. Supply shortages, exasperated by the HBC-NWC rivalry, continuously plagued the expedition. Many voyageurs died of starvation or exhaustion, and one Iroquois scout, Michel Terohaute, was executed on suspicion of cannibalism.[19]

Hoeootoerock went missing following a hunting trip, carrying vital supplies including knives and ammunition. Tatannuaq began a search, but Hoeootoerock was never found, having either died in the harsh environment or deserted the party. Irritated by the party's slow progress on the return journey, Tatannuaq proceeded ahead, but became lost in the unfamiliar terrain. Initially thought dead by the party, he eventually arrived at Fort Enterprise and reunited with the surviving members. Famished and weakened from hunger, the party resorts to eating leather, maggots, and rock tripe.[3][20] Alongside voyageur Joseph Benoit, he reached the Yellowknife chief Akaitcho's camp on November 3, after a two-week journey, to request aid for the other members of the group. After they were joined by other expedition members requesting aid, two small relief parties were sent to Fort Enterprise carrying meat,[21][22] arriving on November 7th and 15th. The expedition party departed, reaching Fort Providence on December 11th, before proceeding to Fort Chipewyan over the following weeks. After recuperating at Fort Chipewyan for several months, the expedition party finally departed to Norway House, reaching the post on June 2, 1822, before disbanding.[23] Tatannuaq was one of only nine survivors of the twenty who began the expedition.[10]

Tatannuaq returned to Fort Churchill in the summer of 1822.[3][23] While at Fort Churchill, he learned that his wife had been married by a brother of Hoeootoerock, who had later killed himself, fearing retaliation. Tattannuaq was warned that one of Hoeootoerock's brothers sought to take revenge on him for this.[24] In August, Tatannuaq met Anglican missionary John West, the first non-Moravian missionary to preach to the Inuit. During West's 1822 and 1823 visits to Churchill and York Factory, Tatannuaq served as his interpreter and converted to Christianity. He returned north to reunite with his family alongside a group of Inuit who had come to see West.[21][25]

Mackenzie River expedition

[edit]After visiting his family, Tatannuaq was hired as an interpreter for another expedition headed by Franklin in the spring of 1825.[26] He departed from York Factory on June 25.[27] Alongside Ooglibuck, another Inuit interpreter,[3] he set out on foot from Churchill to Cumberland House. They joined an advance party alongside various carpenters and boatmen. Franklin's party, having departed from Penetanguishene on Lake Huron, caught up to this group in late June. They walked the Methye Portage, linking the Churchill River basin to the Athabasca.[28] Franklin, accompanied by Tatannuaq, led a small scouting party down the Mackenzie as others made preparations for winter. The group encountered a band of Dene who prepared to fight, but were calmed and surprised by Tatannuaq's presence. Franklin wrote that Tatannuaq reacted modestly to the great interest and admiration of the Dene, who were fascinated by the great distance the Inuk had traveled.[29]

Inuit raid and negotiation

[edit]

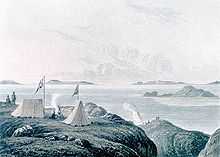

The expedition wintered at a post they named Fort Franklin, on the western shore of the Great Bear Lake. Descending down the Great Bear and Mackenzie rivers in the summer of 1826, the group split in two at the Mackenzie Delta, with Tatannuaq accompanying Franklin's western party of sixteen men. On July 7, they encountered a large group of several hundred Inuit, who pillaged the party's boats despite Tatannuaq's repeated pleas. George Back was able to recover his firearms and shot at the Inuit, causing them to retreat.[26]

Soon after, the expedition encountered a group of eight Inuit who approached them in shallow water off the Arctic coast, requesting to speak with Tatannuaq. Franklin, initially disapproving, eventually allowed him to go to shore unarmed. Tatannuaq spoke to a group of around forty Inuit, scolding them for the raid on the expedition, and threatened that he would have shot and killed them if they had killed any of the Europeans. The Inuit were said to have expressed remorse for the raid, and the party was able to continue without further incident, beyond firing a warning shot at an allegedly hostile group on the return journey. The party disbanded upon returning to Norway House in June 1827, with Tatannuaq reportedly weeping at the end of the expedition.[3][30]

Later life and death

[edit]

From 1827 to 1830 Tatannuaq continued to work for the HBC at Churchill, but would at times make the journey north to visit his family. Aboard the brig Montcalm, he began work as an interpreter at the newly-founded HBC post of Fort Chimo on Ungava Bay (now part of Quebec) in September 1830. Alongside Ooligbuck, he worked there as an interpreter under trader Nicol Finlayson until 1833.[3][21]

In 1833, he learned that George Back was mounting a search for John Ross's second Arctic expedition, presumed lost, and hurried to join. He possibly arrived at York Factory in September 1833. He proceed to Churchill, where, despite an injured leg, he traveled the 1,200 miles (1,900 km) on foot through the winter weather to Fort Resolution, possibly accompanying the post's messenger. Arriving at the post in mid-February 1834, he learned that Back had advanced to Fort Reliance. Alongside a Canadian voyageur and an Iroquois scout, Tatannuaq departed to Fort Reliance. When the party became lost, his two companions abandoned him to return to Fort Resolution, and Tatannuaq was stuck in bad weather around 20 miles (32 km) from the fort, with his body later found at the Rivière à Jean.[3][21] Back did not locate Ross, and later learned that Ross had safely returned to England in early 1834.[31]

Legacy

[edit]Following Tatannuaq's death, Back and George Simpson wrote fondly of his service and character, mourning his death. Finlayson eulogized him less favourably, describing him as a good interpreter but a "bad hunter" and "drunken sot."[3] The butterfly species Callophrys augustinus (brown elfin), first collected by John Richardson in 1827, was named for Tatannuaq.[21] Augustus Lake, a small lake near the Great Bear Lake, was also named for him.[1][32]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Gorham, Harriett; Filice, Michelle (November 12, 2015). "Tattannoeuck (Augustus)". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Toronto: Historica Canada. Archived from the original on January 16, 2024. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Delisle 2019, p. 184.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rowley, Susan (1987). "Tattannoeuck". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto. Archived from the original on January 16, 2024. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ Richardson 1984, p. 28.

- ^ Back 1994, pp. 118–119.

- ^ a b Delisle 2019, p. 185.

- ^ Harper 2022, p. 61.

- ^ Back 1994, p. 119.

- ^ Neatby, Leslie H.; Mercer, Keith (March 8, 2018). "Sir John Franklin". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Toronto: Historica Canada. Archived from the original on January 16, 2024. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Cavell, Janice (2019). "Franklin, Sir John". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto. Retrieved January 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Back 1994, p. 350.

- ^ Delisle 2019, p. 183.

- ^ Richardson 1984, p. xxix.

- ^ Beardsley 2002, p. 66.

- ^ Richardson 1984, p. 25.

- ^ Delisle 2019, p. 186.

- ^ Delisle 2019, p. 187.

- ^ Franklin 1824, pp. 178–188.

- ^ a b Burant, Jim (1987). "Hood, Robert". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ Delisle 2019, pp. 188–189.

- ^ a b c d e Hood 1974, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Richardson 1984, pp. 211–212.

- ^ a b Delisle 2019, p. 191.

- ^ Delisle 2019, p. 192.

- ^ Delisle 2019, pp. 192–193.

- ^ a b Harper 2022, p. 63.

- ^ Delisle 2019, p. 194.

- ^ McGoogan 2017, pp. 92–93.

- ^ McGoogan 2017, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Harper 2022, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Holland, Clive A. (1972). "Back, Sir George". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ "Augustus Lake, Northwest Territories". Open Science and Data Platform. Ottawa: Natural Resources Canada. August 26, 2020. Archived from the original on January 28, 2024. Retrieved January 28, 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Franklin, John (1824). Narrative of a Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea in the Years 1819, 20, 21, and 22. Vol. 2. London: John Murray.

- Hood, Robert (1974). Houston, C. Stuart (ed.). To the Arctic by Canoe, 1819–1821 : The Journal and Paintings of Robert Hood, Midshipman with Franklin. Montreal: Arctic Institute of North America. ISBN 978-0-7735-0192-8.

- Richardson, John (1984). Houston, C. Stuart (ed.). Arctic Ordeal: The Journal of John Richardson, Surgeon-Naturalist with Franklin, 1820–1822. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-0418-9.

- Back, George (1994). Houston, C. Stuart (ed.). Arctic Artist: The Journal and Paintings of George Back, Midshipman with Franklin, 1819-1822. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-6470-1. JSTOR j.ctt810tt.

- Beardsley, Martyn (2002). Deadly Winter: the Life of Sir John Franklin. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-8617-6187-3. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- McGoogan, Ken (2017). Dead Reckoning: The Untold Story of the Northwest Passage. Toronto: HarperCollins Canada. ISBN 978-1-4434-4126-1.

- Delisle, Jea (2019). Interprètes au Pays du Castor (in French). Quebec: Presses de l'Université Laval. ISBN 978-2-7637-4654-8.

- Harper, Kenn (2022). "'A Greater Instance of Courage has not been Recorded' Tatannuaq, the Peacemaker". In Those Days: Inuit and Explorers. Iqualuit: Inhabit Media. pp. 58–66. ISBN 978-1-7722-7422-6.