Taiwan under Qing rule

| Taiwan under Qing rule 臺灣清治時期 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefecture (1683–1885) Province (1885–1895) of the Qing dynasty | |||||||||||||

| 1683–1895 | |||||||||||||

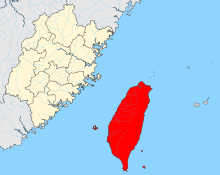

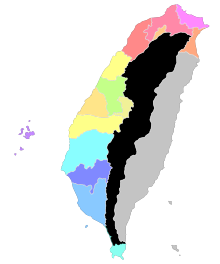

Location of Taiwan Prefecture in Fujian Province, 1820 | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Taiwan-fu (1683–1885) Toatun (1885–87) Taipeh-fu (1887–95) | ||||||||||||

| • Type | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

| 1683 | |||||||||||||

• Taiwan Prefecture, Fujian Province established | 1684 | ||||||||||||

• Taiwan separated from Fujian, converted to its own province | 1887 | ||||||||||||

• Treaty of Shimonoseki (TOS); Taiwan ceded to Japan | 17 April 1895 | ||||||||||||

| 23 May 1895 | |||||||||||||

| 21 October 1895 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Republic of China | ||||||||||||

| History of Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chronological | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Topical | ||||||||||||||||

| Local | ||||||||||||||||

| Lists | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

The Qing dynasty ruled over the island of Taiwan from 1683 to 1895. The Qing dynasty sent an army led by general Shi Lang and defeated the Ming loyalist Kingdom of Tungning in 1683. Taiwan was then formally annexed in April 1684.[1]

Taiwan was governed as Taiwan Prefecture of Fujian Province until the establishment of the Fujian–Taiwan Province in 1887. The Qing dynasty extended its control of Taiwan across the western coast of Taiwan, the western plains, and northeastern Taiwan over the 18th and 19th centuries.[2] The Qing government did not pursue an active colonization policy and restricted Han migration to Taiwan for the majority of its rule out of fear of rebellion and conflict with the Taiwanese indigenous peoples. Han migrants were barred from settling on indigenous land and markers were used to delineate the boundaries of settled areas and mountain dwelling aborigines. Despite Qing restrictions, settlers continued to enter Taiwan and push the boundaries of indigenous territory, resulting in the expansion of Qing borders in Taiwan to encompass all of the western plains and northeastern Taiwan. The lack of state sponsored colonial administration led to frequent rebellions by Han settlers in Taiwan. By the end of Qing rule in 1895, Taiwan's ethnic Han population had increased by over two million with some estimates at over three million, making them the majority demographic on the island. Taiwan was ceded to the Empire of Japan with the Treaty of Shimonoseki in April 1895, following the Qing dynasty's defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War.

History

[edit]Annexation

[edit]

After the defeat of the Kingdom of Tungning at the Battle of Penghu in 1683, the 13-year-old ruler Zheng Keshuang surrendered to the Qing dynasty.[4] The Kangxi Emperor celebrated the defeat of the Ming loyalist regime in Taiwan which had pestered the Qing for decades. He composed two poems in celebration of the victory.[5] Admiral Shi Lang, who had led Qing forces against the Zheng in naval battle, was awarded a hereditary title, the "Marquis of Sea-pacification," on 7 October 1683.[6]

Shi Lang remained in Taiwan for 98 days before returning to Fujian on 29 December 1683. His stay in Taiwan made him feel that annexing Taiwan was of greater importance than expected due to its economic potential. At the conference in Fujian to determine Taiwan's future, some officials from the central government advocated for transporting all of Taiwan's inhabitants to the mainland and abandoning the island.[7] Prior to 1683, Taiwan was associated with a rumored "Island of Dogs," "Island of Women," etc., which were thought, by Han literati, to lie beyond the seas. Taiwan was officially regarded by Kangxi as "a ball of mud beyond the pale of civilization" and did not appear on any map of the imperial domain until 1683.[8] Their primary concern was the defeat of the rebels which had already been accomplished. One argued that defending Taiwan was impossible and increasing defense expenditures was highly unfavorable.[7]

Shi, however, vehemently opposed abandoning Taiwan. Yao Qisheng had also been strongly in favor of annexing Taiwan. On 7 October 1683, Yao stated that though Taiwan had not been part of China, the Zhengs wreaked havoc on the mainland for 20 years after seizing it from the Dutch, and if Taiwan was relinquished then it would once again be occupied by rebels threatening the Chinese coast. Shi argued that to abandon Taiwan would leave it open to other enemies such as criminals, adventurers, and the Dutch. He assured that defending Taiwan would not be cost exorbitant and would only take 10,000 men, while garrisoned forces on the South China coast could be reduced. Shi convinced all the attendees at the Fujian conference, with the exception of the special commissioner from Beijing, Subai, that it was in their best interests to annex Taiwan. On 7 February 1684, Shi sent a memorial to Kangxi with arguments to keep Taiwan, including descriptions of Taiwan's economic products, the cost of relocating Taiwan's inhabitants, and a map of the island.[9] Prior to the Qing dynasty, China was conceived as a land bound by mountains, rivers and seas. The idea of an island as a part of China was unfathomable prior to the Qing frontier expansion effort of the 17th century.[10]

I have personally traveled through Taiwan and seen firsthand the fertility of its wild lands and the abundance of its natural resources. Both mulberry and field crops can be cultivated; fish and salt spout forth from the sea; the mountains are filled with dense forests of tall trees and thick bamboo; there are sulfur, rattan, sugarcane, deerskins, and all that is needed for daily living. Nothing is lacking .... This is truly a bountifully fertile piece of land and a strategic territory.

— Shi Lang

On 6 March 1684, Kangxi accepted Shi's proposal to set up permanent military establishments in Penghu and Taiwan. The final recommendation for annexing Taiwan was presented on 27 May. It was accepted by Kangxi, who authorized the establishment of Taiwan Prefecture, a new prefecture of Fujian Province, with three counties: Taiwan, Zhuluo, and Fengshan. Yang Wenkui was appointed chief commander of Taiwan.[11][12]

Lin Qianguang's description of Taiwan

[edit]

Lin Qianguang was from Changle County, Fujian Province. He held office in Taiwan Prefecture from 1687 to 1691 but lived in Taiwan for several years beforehand and wrote an account of it in 1685.[13]

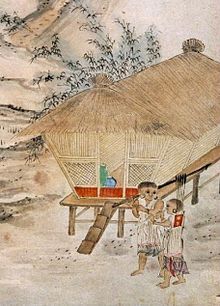

According to Lin, Taiwan was a place of outlaws. Most of the people near the prefectural capital were Zhangzhou and Quanzhou people and beyond there were mostly barbarians, whom he described as stubborn stupid people without family names or ancestral sacrifices. They did not have a calendar or know their own ages, had no terms for their grandparents, and practiced headhunting. The men and women wore no shoes and covered their body with a shirt and cloth for their lower body. The women wrapped their shins in blue cloth and wore flowers or grasses in their hair. Males from the age of 14 or 15 wore rattan girdles. They used fresh grass to stain their teeth black. They pierced their ears and tattooed their bodies. Some tattooed their bodies with Western writing (Dutch). They wore metal bracelets on their arms, sometimes as many as ten, used bird wings to adorn their shoulders, and hung seashells on their necks.[14]

For local officials they had a chief and his deputies, around six or seven persons in a large village and three or four in a small village. They were divided according to their families in the common-house where matters were discussed. The youths slept outside. Some were able to write Western characters (Dutch). They were called jiaoce and handled the accounting.[15]

Girls were preferred since a boy left the family upon marriage. Lin recounted similar courting rituals as described by Chen Di. A feast was held for fellow villagers upon marriage. Tilling was done by the wife. It was common to have multiple sexual partners even when married and there was no shame in sexual activities around children.[16]

They did not have medicine but bathed in the river when ill. They said that Dashi (bodhisattva) would heal them by putting medicine in the water. They bathed in water even during winter. Upon death, they festooned the door and divided the belongings to the survivors. Some belongings were buried with the corpse beneath the bed. After three days, the body was taken out, liquor forced down its throat, and buried without coffin. If the family moved, the body was exhumed and reburied beneath the house.[17]

Their houses were four or five feet high with no partitions between front and back. They were shaped long and narrow like a boat. The beams and posts were painted in various colors. They kept the floor clean of dirt. Behind the house, they planted coconut trees and bamboos in dense groves to avoid the heat. They did not have bedclothes but slept in their garments. There was no kitchen except a cooking pot with a three-legged stand on the ground. They ate gruel around the pot by scooping portions out with a coconut ladle. Rice was rolled up into lumps when eaten. They fermented rice by chewing uncooked rice into paste and then putting it into bamboo tubes. Both rice and clothing were stored in gourds.[18]

They rode on ox-drawn carts. They crossed mountain valleys with the help of vines and crossed streams by jumping from rock to rock. Their spears were about five feet long and effective within a distance of a hundred paces. Their bows were made of bamboo and hemp. The arrows were long and sharp but unfeathered. The fields were ploughed when grass appeared in spring and after the harvest day in the fall, they said a year had passed.[19]

Deeper in the mountains, the people "look like monkeys, less than three feet tall."[19] When spotted, they climbed to the tops of the trees. They had crossbows. Some of them lived in holes.[20]

-

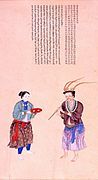

Atayal people

Administration of Taiwan

[edit]

The Qing initially forbade mainlanders from moving to Taiwan and sent most of the Fujianese living in Taiwan back to the mainland, after which only 30,229 remained. With 546 inhabitants in Penghu, 8,108 aborigines, and 10,000 troops, the official population of Taiwan Prefecture was only 50,000. The shortage of manpower compelled local officials to solicit migrants from the mainland despite restrictions imposed by the central court. Sometimes even warships transported civilians to Taiwan.[22] By 1711, illegal migrants from Fujian and Guangdong amounted to tens of thousands yearly.[23] After 1760, restrictions were relaxed and by 1811 there were more than two million Han settlers in Taiwan.[24][25]

The first recorded regulation on the permit system was made in 1712 but it probably existed as early as the formal annexation in 1684. The permit system existed to reduce population pressure on Taiwan. The government believed that Taiwan was unable to support too large a population before it led to conflict. Regulations banned migrants from bringing their families to Taiwan so that settlers would not take root in Taiwan. Another consideration was the migration of unruly people to Taiwan. To prevent undesirables from entering Taiwan, the government recommended only allowing those who had property in mainland China or relatives in Taiwan to enter Taiwan. A regulation to this effect was implemented in 1730 and in 1751 the regulation was reiterated in slightly different terms.[26]

Over the 18th century, regulations on migration remained largely consistent with minor alterations. Early regulations centered on the good character of permit receivers while later regulations reiterated measures such as patrolling and punishment. The only changes were to the status of migrant families.[26] Families in particular were barred from entering Taiwan to ensure that migrants would return to their families and ancestral graves. The overwhelmingly male migrants had few prospects in war-weary Fujian and thus married locally, resulting in the idiom "has Tangshan[a] father, no Tangshan mother" (Chinese: 有唐山公,無唐山媽; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Ū Tn̂g-soaⁿ kong, bô Tn̂g-soaⁿ má).[27][28] Although there is a narrative of widespread intermarriage, this is not supported by historical sources, which only report specific cases of intermarriage. The majority of Han men went back to the mainland to seek marriage and the gender imbalance only lasted until the end of the early Qing period. Due to mass migration, within a few decades, the Han population vastly outnumbered the indigenous people so that even if intermarriage did happen it would have been impossible to meet demand. The fact that indigenous tribes survived all the way up until Japanese colonization indicates that the women did not marry with Han men en masse.[29] Marrying aboriginal women was prohibited in 1737 on the grounds that it interfered in aboriginal life and was used by settlers as a means to claim aboriginal land.[30][31]

In 1732, the governor of Guangdong petitioned to allow families to cross to Taiwan, and for the first time migrant families were allowed to legally enter Taiwan for a period between 1732 and 1740. In 1739, opposition to family migrations claimed that vagrants and undesirables were taking advantage of the system. Families were barred again from 1740 to 1746. In 1760, family crossings to Taiwan became legal again for a short period. Starting in 1771, Qing restrictions on cross-strait migration began to relax as they realized that the policies were unenforceable. Even during periods of legal migration, many more individuals chose to hire illegal ferry service rather than to deal with official procedures. After lifting restrictions on family crossings in 1760, only 48 families, or 277 people, requested permits after a year. The vast majority of them were government employee families. In comparison, within a ten-month period in 1758–1759, nearly 60,000 people were arrested for illegal crossings. In 1790, an office was set up to manage civilian travel between Taiwan and the mainland, and the Qing government ceased to actively interfere in cross-strait migration. Policy against secret crossings were briefly revived in 1834 and 1838.[23][32][31] In 1875, all restrictions on entering Taiwan were repealed.[23]

| Qing regulations on migration to Taiwan[33][23] | |

|---|---|

| Year | Regulation |

| 1684 | Permit required to enter Taiwan. Family migration not allowed. |

| 1712 | Permit required to enter Taiwan. Officials ordered not to issue permit irresponsibly; "Good subjects" were allowed to apply for Taiwanese residence. |

| 1729 | Illegal crossing to be policed and officials punished if negligent. |

| 1730 | Settlers in Taiwan who did not have a family to be expelled and those who had family and property but engaged in unruliness to be punished according to law. |

| 1732 | Wives and children allowed to accompany migrants to Taiwan. |

| 1734 | Boat owners/operators to be punished if taking passengers illegally. |

| 1736 | Illegal crossing to be policed and officials punished if negligent. |

| 1737 | Permit system to be tightened and details of boats to Taiwan and their crews to be recorded. Local officials in Taiwan to record details of local residents. |

| 1740 | Boat owners/operators taking illegal passengers to be punished at the location of landing. |

| 1745 | Only wives and children may be taken to Taiwan by migrants. |

| 1747 | Procedures prescribed for taking families to Taiwan, and officials to be punished if permits issued irresponsibly. |

| 1761 | Permit required to enter Taiwan and the only port of departure was Xiamen. Illegal crossing to be policed. Officials to be punished if negligent and rewarded if diligent. Family reunion migration banned. |

| 1770 | Illegal crossing to be policed. Official punished if negligent and rewarded if diligent; boat owners and passengers punished for breaches. |

| 1772 | Punish a range of people if involved in illegal crossing business, including organizers, boat crews and passengers. |

| 1784 | Taiwan settlers allowed to return to their place of origin in mainland China without a permit. They could only depart from Luermen. Other ports strictly policed for arrivals and departures. |

| 1788 | Open another port in Taiwan to reduce illegal crossings. |

| 1789 | Officials not to extort applicants going to Taiwan so as to reduce illegal crossings. |

| 1800 | Illegal crossing to be policed. Officials punished if negligent and rewarded if diligent. Settlers in Taiwan could apply for residency if they had family and property, otherwise to be expelled to their place of origin. |

| 1801 | Illegal crossing policed. Officials to be punished if negligent. |

| 1875 | Restrictions on migration abolished. |

-

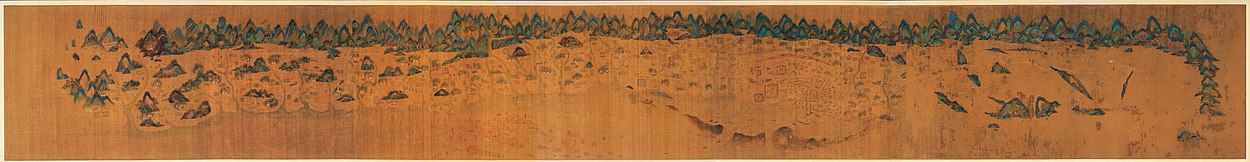

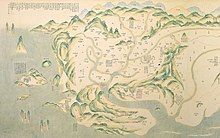

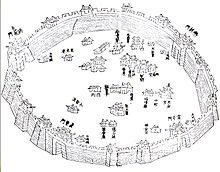

Taiwan County (modern Tainan) in 1747

-

Taiwan City (Tainan), 1807

-

Taiwan County (Tainan), 19th century

Settler expansion (1684–1795)

[edit]

During the reigns of the Kangxi (r. 1661–1722), Yongzheng (r. 1722–1735), and Qianlong (r. 1735–1796) emperors, the Qing court deliberately restricted the expansion of territory and government administration in Taiwan. The purpose of attacking the Zhengs in Taiwan was to eliminate the enemy Ming remnant regime and the annexation of Taiwan was primarily for security reasons. Taiwan was garrisoned with 8,000 soldiers at key ports and civil administration was kept to a minimum with few changes from the previous Zheng administration. Three prefectures nominally covered the entire western plains – Taiwan, Fengshan, and Zhuluo – but effective administration covered a smaller area. A government permit was required for settlers to go beyond the Dajia River at the mid-point of the western plains. In 1715, the governor-general of Fujian-Zhejiang recommended land reclamation in Taiwan but Kangxi was worried that this would cause instability and conflicts.[34]

Under the reign of Yongzheng, the Qing extended control over the entire western plains, but this was to better control the settlers and maintain security. The quarantine policies were maintained. In 1723, Zhuluo County was split to form a new county, Changhua, which resided north of the mid-point of the western plains. In 1731, a Tamsui subprefecture was created in the north, effectively extending government control from the southwest to the north. This was not an active colonization policy but a reflection of continued illegal crossings and land reclamation in the north. In 1717, the Zhuluo County magistrate argued that the area was too large to be effectively controlled, leading to disorder and lawlessness, and needed to be divided. The government finally reacted after a major settler rebellion, the Zhu Yigui uprising, occurred in 1721, and Zhuluo County was created in 1723. Lan Dingyuan, an advisor to Lan Tingzhen, who led forces against the rebellion, advocated for expansion and land reclamation to strengthen government control over the Chinese settlers. He wanted to convert the aborigines to Han culture and turn them into subjects of the Qing.[35]

Under the reign of Qianlong, the administrative structure of Taiwan remained largely unchanged. In 1744, officials recommended letting settlers reclaim land but Qianlong dismissed their recommendations. This started to change after the Lin Shuangwen rebellion in 1786, after which Qianlong agreed that leaving fertile lands to unproductive aborigines only attracted illegal settlers. He came to believe that Taiwan was the "important coastal frontier territory" and "the important fence line of the five [coastal] provinces."[36]

The Qing did little to administer the aborigines and rarely tried to subjugate or impose cultural change upon them. Aborigines were classified into two general categories: acculturated aborigines (shufan) and non-acculturated aborigines (shengfan). Sheng is a word used to describe uncooked food, unworked land, unripened-fruit, unskilled labor or strangers, while shu bears the opposite meaning. To the Qing, shufan were aborigines who paid taxes, performed corvée, and had adopted Han Chinese culture to some degree. When the Qing annexed Taiwan, there were 46 aboriginal villages under government control: 12 in Fengshan and 34 in Zhuluo. These were likely inherited from the Zheng regime. In the Yongzheng period, 108 aboriginal villages submitted as a result of encouragement and enticement from the Taiwan regional commander, Lin Liang. Shengfan who paid taxes but did not perform corvée and did not practice Han Chinese culture were called guihua shengfan (submitted non-acculturated aborigines).[37]

The Qianlong administration forbade enticing aborigines to submit due to fear of conflict. In the early Qianlong period, there were 299 named aboriginal villages. Records show 93 shufan villages and 61 guihua shengfan villages. The number of shufan villages remained stable throughout the Qianlong period. Two aboriginal affairs sub-prefects were appointed to manage aboriginal affairs in 1766. One was in charge of the north and the other in charge of the south, both focused on the plains aborigines. Boundaries were built to keep the mountain aborigines out of settlement areas. The policy of marking settler boundaries and segregating them from aboriginal territories became official policy in 1722 in response to the Zhu Yigui uprising. Fifty-four stelae were used to mark crucial points along the settler-aboriginal boundary. Han settlers were forbidden from crossing into aboriginal territory but settler encroachment continued, and the boundaries were rebuilt in 1750, 1760, 1784, and 1790. Settlers were forbidden from marrying aborigines as marriage was one way settlers obtained land. While the settlers drove colonization and acculturation, the Qing policy of quarantine dented the impact on aborigines, especially mountain aborigines.[32]

| Taiwan Population Data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Chinese | Aboriginal | Total |

| 1623 | 1,500[38] | ||

| 1652 | 25,000[39] | ||

| 1654 | 100,000[40] | ||

| 1661 | 35,000[41] | ||

| 1664 | 50,000[42] | ||

| 1683 | 120,000[43] | ||

| 1756 | 600,147[44] | ||

| 1777 | 839,800[44] | ||

| 1782 | 912,000[44] | ||

| 1790 | 950,000[45] | ||

| 1811 | 1,944,747[46] | ||

| 1824 | 1,786,883[44] | ||

| 1893 | 2,545,000[47] | ||

| 1905 | 2,492,784[42] | 82,795[42] | 3,039,751[42] |

| 1925 | 3,993,408[42] | ||

| 1935 | 5,212,426[42] | ||

| 1945 | 6,560,000[42] | ||

| 1955 | 9,078,000[42] | ||

| 1958 | 10,000,000[48] | ||

| 1965 | 12,628,000[42] | ||

| 1975 | 16,150,000[42] | ||

| 1985 | 19,258,000[42] | ||

| 1995 | 21,300,000[42] | ||

| 2015 | 546,700[49] | ||

| 2018 | 23,550,000[50] |

Administrative expansion (1796–1874)

[edit]

Qing quarantine policies were maintained in the early 19th century but attitudes towards aboriginal territories started to change. Local officials repeatedly advocated for the colonization of aboriginal territories, especially in the cases of Gamalan and Shuishalian. The Gamalan or Kavalan people were situated in modern Yilan County in northeastern Taiwan. It was separated from the western plains and Tamsui (Danshui) by mountains. There were 36 aboriginal villages in the area and the Kavalan people had started paying taxes as early as the Kangxi period (r. 1661–1722), but they were non-acculturated guihua shengfan aborigines.[51]

In 1787, a Chinese settler named Wu Sha tried to reclaim land in Gamalan but was defeated by aborigines. The next year, the Tamsui sub-prefect convinced the Taiwan prefect, Yang Tingli, to support Wu Sha. Yang recommended subjugating the natives and opening Gamalan for settlement to the Fujian governor but the governor refused to act due to fear of conflict. In 1797, a new Tamsui sub-prefect issued permit and financial support for Wu to recruit settlers for land reclamation, which was illegal. Wu's successors were unable to register the reclaimed land on government registers. Local officials supported land reclamation but could not officially recognize it.[52]

In 1806 it was reported that a pirate, Cai Qian, was within the vicinity of Gamalan. Taiwan Prefect Yang once again recommended opening up Gamalan, arguing that to abandon it would cause trouble on the frontier. Later another pirate band tried to occupy Gamalan. Yang recommended to the Fuzhou General Saichong'a the establishment of administration and land surveys in Gamalan. Saichong'a initially refused but then changed his mind and sent a memorial to the emperor in 1808 recommending the incorporation of Gamalan. The issue was discussed by the central government officials and for the first time, one official went on record saying that if aboriginal territory was incorporated, not only would it end the pirate threat but the government would stand to profit from the land itself. In 1809, the emperor ordered for Gamalan to be incorporated. The next year an imperial decree for the formal incorporation of Gamalan was issued and a Gamalan sub-prefect was appointed.[53]

Unlike Gamalan, debates on Shuishalian resulted in its continued status as a closed-off area. Shuishalian refers to the upstream areas of the Zhuoshui River and Wu River in central Taiwan. The inner mountain area of Shuishalian was inhabited by 24 aboriginal villages and six of them occupied the flat and fertile basin area. The aboriginals had submitted as early as 1693 but they remained non-acculturated. In 1814, some settlers were able to obtain reclamation permits through fabricating aboriginal land lease requests. In 1816, the government sent troops to evict the settlers and destroy their strongholds. Stelae were erected demarcating the land forbidden to Chinese settlers.[54]

In 1823, the aboriginal affairs sub-prefect for the north, Deng Chuan'an, recommended opening up inner Shuishalian. The Gamalan sub-prefect, Yao Ying, discouraged this, stating that the administrative costs were too high and the aborigines uncooperative. In 1841 the issue was brought up again, but this time it was recommended that all of Taiwan be opened up. The Daoguang Emperor ordered the Fujian-Zhejiang governor-general to investigate reclaiming land in Taiwan to increase revenue for the maritime defense. The plan was shelved after the cost was deemed too high. In 1846, a new Fujian-Zhejiang governor-general, Liu Yunke, argued that opening up inner Shuishalian would be beneficial. The central government officials were unconvinced. Liu visited Shuishalian and detailed a report on the aborigines and their land with the purpose of encouraging the central court to open up the land for settlement. Still the central court refused to open up the area. In 1848, a Taiwan circuit intendant recommended letting Shuishalian aborigines lease their land to settlers. This suggestion was ignored.[55] The subject of land reclamation continued to be a topic of discussion and the Tamsui subprefecture gazetteer in 1871 openly called for "opening the mountains and subjugating the aborigines."[56]

| Registered taxable land area in Qing Taiwan[57] | |

|---|---|

| Year | Jia[58] |

| 1684 | 18,454 |

| 1710 | 30,110 |

| 1735 | 50,517 |

| 1762 | 63,045 |

| 1893–95 | 361,417 |

Expansion in reaction to crises (1875–1895)

[edit]

In 1874, Japan invaded aboriginal territory in southern Taiwan in what is known as the Mudan Incident (Japanese invasion of Taiwan (1874)). For six months Japanese soldiers occupied southern Taiwan and Japan argued that it was not part of the Qing dynasty. The result was the payment of an indemnity by the Qing in return for the Japanese army's withdrawal.[59][60][61][62][63]

The imperial commissioner for Taiwan, Shen Baozhen, argued that "the reason that Taiwan is being coveted by [Japan] is that the land is too empty."[64] He recommended subjugating the aborigines and populating their territory with Chinese settlers. As a result, the administration of Taiwan was expanded and campaigns against the aborigines were launched. A new prefecture, Taipeh Prefecture, was created. Gamalan subprefecture became Yilan County. Tamsui subprefecture was divided into Tamsui and Hsinchu. A new county, Hengchun, was created in the south. The two sub-prefects responsible for aboriginal affairs were moved to inner Shushalian (Puli) and eastern Taiwan (Beinan), the focal points for colonization. Starting in 1874, mountain roads were built to make the region more accessible and aborigines were brought into formal submission to the Qing. In 1875, the ban on entering Taiwan was lifted.[64] In 1877, 21 guidelines on subjugating aborigines and opening the mountains were issued. Agencies for recruiting settlers were established on the coastal mainland and in Hong Kong. However efforts to promote settlement in Taiwan petered out soon after.[65]

The Sino-French War broke on in 1883 and the French occupied Keelung in northern Taiwan in 1884. The French army withdrew in 1885. Efforts to settle in aboriginal territories were renewed under the governance of Liu Mingchuan, the Fujian governor and Taiwan defense commissioner. Administering Taiwan became his sole focus in 1885 and the administration of Fujian was left to the governor-general. Another prefecture, Taiwan Prefecture, was created in the western plains, while the former Taiwan Prefecture was renamed Tainan. Three new counties, Taiwan, Yunlin, and Miaoli, were created by dividing the existing administrative units. Eastern Taiwan, the Beinan subprefecture, was governed by a new Taitung Department (eastern Taiwan department). In the subsequent years, the subprefectures of Puli, Keelung, and Nanya were added.[66] In 1887, Taiwan became its own province. For five years, Fujian provided Taiwan with a yearly transition subsidy of 400,000 taels, or 10 percent of Taiwan's annual revenue. During Liu's tenure, Taiwan's capital was shifted from Tainan to modern Taichung. Taipei was built up as a temporary capital and then became the permanent capital in 1893. Liu's efforts to increase revenues sugar, camphor, and imports were mixed due to foreign pressure to reduce levies. Revenues from coal mines and steamship lines became a primary part of Taiwan's annual budget. A cadastral reform survey was undertaken from June 1886 to January 1890 that met with opposition in the south. The receipts from the land tax reform constituted a sizable gain, however they fell short of expectations.[67]

Under Liu's governance, a number of technological innovations were introduced to Taiwan, including electric lighting, modern weaponry, a railway, cable and telegraph lines, a local steamship service, and machinery for lumbering, sugar refining, and brick making. A telegraph line from Tainan to Tamsui was constructed in 1886–88 and a railway connecting Keelung, Taipei, and Hsinchu was built. These first efforts were met with mixed results. The telegraph line could only function in bursts of a week due to a difficult overland connection and the railway required an overhaul, serviced small rolling stock, and carried little freight.[69] Taiwan was not a very attractive place for laborers, most of whom wanted to go to Southeast Asia. Few settlers went to Taiwan and those that did were accosted by aborigines and the harsh climate. Governor Liu was criticized for the high cost and little gain from the colonization activities. Liu resigned in 1891 and the colonization efforts ceased with much of the reclaimed land going to waste.[70]

A Taiwan Pacification and Reclamation Head Office was established with eight pacification and reclamation bureaus. Four bureaus were located in eastern Taiwan, two in Puli (inner Shuishalian), one in the north, and one on the western border of the mountains. By 1887, about 500 aboriginal villages, or roughly 90,000 aborigines had formally submitted to Qing rule. This number increased to 800 villages with 148,479 aborigines over the following years. However the cost of getting them to submit was exorbitant. The Qing offered them materials and paid village chiefs monthly allowances. Not all the aborigines were under effective control and land reclamation in eastern Taiwan occurred at a slow pace.[70] From 1884 to 1891, Liu launched more than 40 military campaigns against the aborigines with 17,500 soldiers. The eastward expansion ended after the defeat of the Mkgogan and Msbtunux due to the fierceness of their resistance. A third of the invasion force was killed or disabled in the conflict, amounting to a costly failure.[69][71]

By the end of the Qing period, the western plains were fully developed as farmland with about 2.5 million Chinese settlers. The mountainous areas were still largely autonomous under the control of aborigines. Aboriginal land loss under the Qing occurred at a relatively slow pace compared to the following Japanese colonial period due to the absence of state sponsored land deprivation for the majority of Qing rule.[72][47] In the 50-year period of Japanese rule that followed, the Taiwanese aborigines lost their right to legal ownership of land and were confined to small reserves one-eighth the size of their ancestral lands.[73] However even had Japan not taken over Taiwan, the plains aborigines were on the way to losing their residual rights to land. By the last years of Qing rule, most of the plains aborigines had been acculturated to Han culture, around 20–30% could speak their mother tongues, and gradually lost their land ownership and rent collection rights.[74]

| Year | Prefecture | County | Subprefecture |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1684 | Taiwan | Taiwan, Zhuluo, Fengshan | |

| 1723 | Taiwan | Taiwan, Zhuluo, Fengshan, Zhanghua | |

| 1727 | Taiwan | Taiwan, Zhuluo, Fengshan, Zhanghua | Penghu |

| 1731 | Taiwan | Taiwan, Zhuluo, Fengshan, Zhanghua | Penghu, Danshui |

| 1812 | Taiwan | Taiwan, Jiayi, Fengshan, Zhanghua | Penghu, Danshui, Gamalan |

| 1875 | Taiwan, Taibei | Taiwan, Fengshan, Zhanghua, Jiayi, Hengchun, Yilan, Xinzhu, Danshui | Penghu, Beinan, Pulishe, Lugang, Jilong |

| 1885 | Taiwan, Taibei, Tainan, Taidong Zhili Region | Taiwan, Fengshan, Zhanghua, Jiayi, Hengchun, Yilan, Xinzhu, Danshui, Anping, Miaoli, Yunlin | Penghu, Pulishe, Jilong, Nanya |

Rebellions

[edit]

Aboriginal

[edit]In 1723, aborigines living in Dajiaxi village along the central coastal plain rebelled. Government troops from southern Taiwan were sent to put down this revolt, but in their absence, Han settlers in Fengshan County rose up in revolt under the leadership of Wu Fusheng, a settler from Zhangzhou.[76] By 1732, five different ethnic groups were in revolt but the rebellion was defeated by the end of the year.[76]

During the Qianlong period (1735–1796), the 93 shufan acculturated aborigine villages never rebelled and over 200 non-acculturated aboriginal villages submitted.[77] In fact, during the 200 years of Qing rule in Taiwan, the plains aborigines rarely rebelled against the government and the mountain aborigines were left to their own devices until the last 20 years of Qing rule. Most of the rebellions, of which there were more than 100 during the Qing period, were caused by Han settlers.[78][79] The idom, "Every three years an uprising, every five years a rebellion"(三年一反、五年一亂), was used primarily to describe commotions that occurred during the 30-year period between 1820-1850.[80][81]

Zhu Yigui

[edit]Zhu Yigui, also known as the "Duck King",[82] was a settler from Fujian. He became the owner of a duck farm in Taiwan's Luohanmen (modern Kaohsiung). Zhu was known among locals for his generous conduct and persistent fight against immoral conduct. In 1720, there was an upset among merchants, fishermen, and farmers in Taiwan due to increased taxation. They gathered around Zhu, who shared the same surname with the Ming dynasty's royal family, and supported him in mobilizing discontent Chinese into an anti-Qing rebellion.[83] Zhu was declared the Ming Emperor and efforts were made to imitate Ming style clothing with performance costumes.[82] Hakka leader Lin Junying from the south also joined the rebellion. In March 1720, Zhu and Lin attacked the Qing garrison at Taiwan County and defeated them in April. In less than two weeks, the rebels had defeated Qing forces in all of Taiwan. The Hakka troops left Zhu to follow Lin north. The Qing sent a fleet under the command of Shi Shibian (son of Shi Lang) with an army of 22,000 troops. A month later, the rebellion was defeated and Zhu was executed in Beijing.[83]

Lin Shuangwen

[edit]

In 1786, members of the Tiandihui (Heaven and Earth society) secret society were arrested for failing to make tax payments. The Tiandihui broke into the jail, killed the guards, and rescued their members. When Qing troops were sent into the village and tried to arrest Lin Shuangwen, the leader of the Tiandihui and a settler from Fujian, led his forces to defeat the Qing troops.[84] Many of the rebel army's troops came from new arrivals from mainland China who could not find land to farm. They joined the Tiandihui for protection.[82] Lin attacked Changhua County, killing 2,000 civilians. In early 1787, 50,000 Qing troops under Li Shiyao from the mainland were sent to put down the rebellion. The two sides fought to a stalemate for six months. Lin tried to enlist the support of the Hakka people but not only did they refuse, they sent their troops to support the Qing.[84] Despite the Tiandihui's ostensibly anti-Qing stance, its members were generally anti-government and were not motivated by ethnic or national interest, resulting in social discord and political chaos. Some civilians aided the Qing against the rebels.[82] In 1788, a fresh force of 10,000 Qing troops led by Fuk'anggan and Hailanqa were sent to Taiwan.[85] They successfully defeated the rebellion shortly after arriving. Lin was executed in Beijing in April 1788.[84] The Qianlong Emperor gave Zhuluo County its modern name Chiayi (lit. commendable righteousness) for resisting the rebels.[82]

Invasions

[edit]Maurice Benyovszky

[edit]

Slovakia born Maurice Benyovszky is possibly the first European to land on Taiwan's east coast, but it is uncertain whether the events surrounding his landing actually occurred. According to a 1790 English translation of the Memoirs and Travels of Mauritius Augustus Count de [Benovsky], an eighteen-person party landed on Taiwan's eastern shores in 1771. They met a few people and asked them for food. They were taken to a village and fed rice, pork, lemons, and oranges. They were offered a few knives. While making their way back to the ship, they were hit by arrows. The party fired back and killed six attackers. Near their ship, they were ambushed again by 60 warriors. They defeated their attackers and captured five of them. Benyovszky wanted to leave but his associates insisted on staying. A larger landing party rowed ashore a day later and were met by 50 unarmed locals. The party headed to the village and slaughtered 200 locals while eleven of the party members were injured. They then left and headed north with the guidance of locals.[86]

Upon reaching a "beautiful harbor" they met Don Hieronemo Pacheco, a Spaniard who had been living among the aborigines for seven to eight years. The locals were grateful toward Benyovszky for killing the villagers, who they considered their enemies. Paheco told Benyovszky that the western side of the island was ruled by the Chinese but the rest was independent or inhabited by aborigines. Paheco told Benyovszky that it would take very little to conquer the island and drive out the Chinese. On the third day, Benyovszky was calling the harbor "Port Maurice" after himself. Conflict broke out again as the party was fetching fresh water and three members were killed. The party executed their remaining prisoners and slaughtered a boatful of the enemies. By the end, they had killed 1,156 and captured 60 aborigines. They were visited by a prince named Huapo who believed Benyovszky was prophesied to free them from the "Chinese yoke."[86] With Benyovszky's arms, Huapo then defeated his Chinese aligned foes. Huapo gifted Benyovszky's crew with gold and other valuables to try to get them to stay but Benyovszky wanted to go so that he could see his wife and son.[86]

There are reasons to suspect this account of events is either exaggerated or fabricated. Benyovszky's exploits have been questioned by several experts over the years. Ian Inkster's "Orientat Enlightenment: The Problematic Military Claims of Count Maurice Auguste Conte de Benyowsky in Formosa during 1771" criticizes the Taiwan section specifically. The population of Taiwan given by Benyovszky's account is inconsistent with estimates of that time. The stretch of coast he visited likely only had 6,000 to 10,000 inhabitants but somehow the prince was able to gather 25,000 warriors to fight 12,000 enemies.[86] Even in Father de Mailla's account of Taiwan in 1715, in which he portrayed the Chinese in a very negative manner, and spoke of the entire east being in rebellion against the west, the aborigines were still unable to put up a fighting force of more than 30 or 40 armed with arrows and javelins.[87] Huaco was also mentioned to have nearly 100 horsemen and had 68 to spare for the European party's use. Horses were introduced to Taiwan starting in the Dutch period but it is highly unlikely that aborigines of the northeast coast had acquired so many that they could train them for large scale warfare.[86] In other 18th century accounts, it was mentioned that horses were in such scarce supply that Chinese oxen were used as substitutes.[88]

Opium War

[edit]By 1831, the East India Company decided it no longer wanted to trade with the Chinese on their terms and planned more aggressive measures. A Prussian missionary and linguist, Karl F.A. Gutzlaff, was sent to explore Taiwan. He published his experiences in Taiwan in 1833 confirming its rich resources and trade potential. Given the strategic and commercial value of Taiwan, there were British suggestions in 1840 and 1841 to seize the island. William Huttman wrote to Lord Palmerston pointing out "China’s benign rule over Taiwan and the strategic and commercial importance of the island."[89] He suggested that Taiwan could be occupied with only a warship and less than 1,500 troops, and the English would be able to spread Christianity among the natives as well as develop trade.[90]

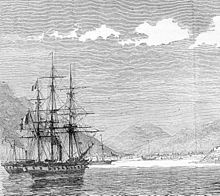

In 1841, during the First Opium War, the British tried to scale the heights around the harbor of Keelung three times but failed.[91] In September, the British transport ship Nerbudda became shipwrecked near Keelung Harbour due to a typhoon. The captain and a handful of English officers escaped safely, however most of the crew including 29 Europeans, 5 Filipinos, and 240 Indian lascars, were rescued by locals and handed over to Qing officials in Tainan, the capital of Taiwan. In October 1841, HMS Nimrod sailed to Keelung to search for the Nerbudda survivors, but after Captain Joseph Pearse found out that they were sent south for imprisonment, he ordered the bombardment of the harbour and destroyed 27 sets of cannon before returning to Hong Kong. The brig Ann also shipwrecked in March 1842 and another 54 survivors were taken. The Taiwan Qing commanders, Dahonga and Yao Ying, filed a disingenuous report to the emperor, claiming to have defended against an attack from the Keelung fort. Most of the survivors—over 130 from the Nerbudda and 54 from the Ann—were executed in Tainan in August 1842. The false report was later discovered and the officials in Taiwan punished. The British wanted them executed but they were only given different postings on the mainland, which the British were not aware of until 1845.[89]

Rover incident

[edit]

On 12 March 1867, the American barque Rover shipwrecked offshore at the southern tip of Taiwan. The vessel sank but the captain, his wife, and some men escaped on two boats. One boat landed at a small bay near the Bi Mountains inhabited by the Koaluts (Guizaijiao) tribe of the Paiwan people. The Koaluts aborigines captured them and mistook the captain's wife for a man. They killed her. The captain, two white men, and the Chinese sailors save for one who managed to escape to Takau, were also killed. The Cormorant, a British steamer, tried to help and landed near the shipwreck on 26 March. The aborigines fired muskets and shot arrows at them, forcing them to retreat. The American Asiatic Fleet's Admiral Bell also landed at the Bi Mountains where they got lost, suffered heatstroke, and then was ambushed by the aborigines, losing an officer.[92][93]

Le Gendre, the US Consul, blamed the Qing dynasty for the failure and demanded that they send troops to help him negotiate with the aborigines. He also hoped that the Qing would permanently station troops to prevent further killings by the aborigines. On 10 September, Garrison Commander Liu Mingcheng led 500 Qing troops to southern Taiwan with Le Gendre. The remains were recovered. The aboriginal chief, Tanketok (Toketok), explained that a long time ago the white men came and almost exterminated the Koaluts tribe and their ancestors passed down their desire for revenge. They came to an oral agreement that the mountain aborigines would not kill any more castaways, would care for them and hand them over to the Chinese at Langqiao.[94]

Le Gendre visited the tribe again in February 1869 and signed an agreement with them in English. It was later discovered that Tanketok did not have absolute control over the tribes and some of them paid him no heed. Le Gendre castigated China as a semi-civilized power for not fulfilling the obligation of the law of nations, which is to seize the territory of a "wild race" and to confer upon it the benefits of civilization. Since China failed to prevent the aborigines from killing subjects or citizens of civilized countries, "we see the rights of the Emperor of China over aboriginal Formosa, such as we have said, are not absolute, as long as she remains uncivilized..."[95] Le Gendre later moved to Japan and worked with the Japanese government as a foreign advisor on their China policy, including the development of the concept of the "East Asian crescent". According to the "East Asian crescent" concept, Japan should control Korea, Taiwan, and Ryukyu to affirm its position in East Asia.[96]

Mudan incident

[edit]

In December 1871, a Ryukyuan vessel shipwrecked on the southeastern tip of Taiwan and 54 sailors were killed by aborigines. Four tribute ships were returning to the Ryukyu Islands when they were blown off course on 12 December. Two ships were pushed towards Taiwan. One of them landed on Taiwan's western coast and made it back home with the help of Qing officials. The other one crashed into the eastern coast of southern Taiwan near Bayao Bay. There were 69 passengers and 66 managed to make it to shore. They met two Chinese men who told them not to travel inland where the dangerous Paiwan people were.[97]

According to the survivors, the Chinese robbed them and they decided to part ways. On 18 December they headed westward and encountered aboriginal men, presumably Paiwanese. They followed the Paiwanese to a small settlement, Kuskus, where they were given food and water. According to Kuskus local Valjeluk Mavalu, the water was a symbol of protection and friendship. The deposition claims they were robbed by their Kuskus hosts during the night. In the morning they were ordered to stay put while hunters left to search for game to provide a feast. Alarmed by the armed men and rumors of head hunting, the Ryukyuans departed while the hunting party was away. They found shelter in the home of a 73 year old Hakka trading-post serviceman, Deng Tianbao. The Paiwanese men found the Ryukyuans and dragged them out, slaughtering them, while others died in a fight or were caught trying to escape. Nine Ryukyuans hid in Deng's home. They moved to another Hakka settlement Poliac (Baoli) where they found refuge with Deng's son-in-law, Yang Youwang. Yang arranged for the ransom of three men and sheltered the survivors for 40 days before sending them to Taiwan Prefecture (modern Tainan). The Ryukuans headed home in July 1872.[98]

It is uncertain what caused the Paiwanese to murder the Ryukyuans. Some say the Ryukyuans did not understand Paiwanese guest etiquette, they ate and ran, or that their captors could not find ransom and therefore killed them. According to Lianes Punanang, a Mudan local, 66 men who could not understand the local languages entered Kuskus and began taking food and drink, disregarding village boundaries. Efforts to aid the strangers with food and drink strained Kuskus resources. They were finally killed for their misdeeds. The shipwreck and murder of the sailors came to be known as the Mudan incident although it did not take place in Mudan (J. Botan), but at Kuskus (Gaoshifo).[99]

The Mudan incident did not immediately cause any concern in Japan. A few officials knew of it by mid-1872 but it was not until April 1874 that it became an international concern. The repatriation procedure in 1872 was by the books and had been a regular affair for several centuries. From the 17th to 19th centuries, the Qing had settled 401 Ryukyuan shipwreck incidents both on the coast of mainland China and Taiwan. The Ryukyu Kingdom did not ask Japanese officials for help regarding the shipwreck. Instead its king, Shō Tai, sent a reward to Chinese officials in Fuzhou for the return of the 12 survivors.[100]

Japanese expedition

[edit]

On 30 August 1872, Sukenori Kabayama, a general of the Imperial Japanese Army, urged the Japanese government to invade Taiwan's tribal areas. In September, Japan dethroned the king of Ryukyu. On 9 October, Kabayama was ordered to conduct a survey in Taiwan. In 1873, Tanemomi Soejima was sent to communicate to the Qing court that if it did not extend its rule to the entirety of Taiwan, punish murderers, pay victims' families' compensation, and refused to talk about the matter, Japan would take care of the matter. The Foreign Minister Sakimitsu Yanagihara believed that the perpetrators of the Mudan incident were "all Taiwan savages beyond Chinese education and law."[101] Japan justified sending an expedition to Taiwan through linguistic interpretation of "化外之民" to mean not part of China. Chinese diplomat Li Hongzhang rejected the claim that the murder of Ryukyuans had anything to do with Japan once he learned of Japan's aspirations.[102] However, after communications between the Qing and Yanagihara, the Japanese took their explanation to mean that the Qing government had not opposed Japan's claims to sovereignty over the Ryukyu Islands, disclaimed any jurisdiction over Aboriginal Taiwanese, and had indeed consented to Japan's expedition to Taiwan.[103] In the eyes of Japan and the foreign advisor Le Gendre, the aborigines were "savages" who had no sovereign or international status, and therefore their territory was "terra nullius", free to be seized for Japan.[104] The Qing argued that like in many other countries, the administration of the government did not stretch to every part of a country, similar to the Indian territories in the United States or aboriginal territories in Australia and New Zealand, a view Le Gendre also took before his employment by the Japanese.[105]

Japan had already sent a student, Kurooka Yunojo, to conduct surveys in Taiwan in April 1873. Kabayama reached Tamsui on 23 August disguised as a merchant and surveyed eastern Taiwan.[102] On 9 March 1874, the Taiwan Expedition prepared for its mission. The magistrate of the Taiwan Circuit learned of the impending Japanese invasion from a Hong Kong newspaper quoting a Japanese news item and reported it to Fujian authorities.[106] Qing officials were taken by complete surprise due to the seemingly cordial relations with Japan at the time. On 17 May, Saigō Jūdō led the main force, 3,600 strong, aboard four warships in Nagasaki headed to Tainan.[107] On 6 June, the Japanese emperor issued a certificate condemning the Taiwan "savages" for killing our "nationals", the Ryukyuans killed in southeastern Taiwan.[108]

On 3 May 1874, Kusei Fukushima delivered a note to Fujian-Zhejiang Governor Li Henian announcing that they were heading to savage territory to punish the culprits. On 7 May, a Chinese translator, Zhan Hansheng, was sent ashore to establish peaceful relations with tribes other than the Mudan and Kuskus. Afterwards American foreign officers and Fukushima landed at Checheng and Xinjie. They tried to use Baxian Bay at Qinggangpu as their barracks but heavy rain flooded the site a few days later so the Japanese moved to the southern end of Langqiao Bay on 11 May. They learned that Tanketok had died and invited the Shemali tribe for talks. Japanese scouts fanned out and were met by attacks by aborigines. On 21 May, a 12-member scout party was ambushed and two were wounded. The Japanese camp sent 250 reinforcements and searched the villages. The next day, Samata Sakuma encountered Mudan fighters, around 70 strong, occupying a commanding height. A twenty-men party climbed the cliffs and shot at the Mudan people, forcing them to flee. The Mudan lost 16 men including their tribal leader, Agulu. The Japanese lost seven with 30 injured.[109]

The Japanese army split into three forces and headed in different directions, the south, north, and central routes. The south route army was ambushed by the Kuskus tribe and lost three soldiers. A counterattack defeated the Kuskus fighter and the Japanese burnt their villages. The central route was attacked by Mudan and two or three soldiers were wounded. The Japanese burnt their villages. The north route attacked the Nünai village. On 3 June, they burnt all the villages that had been occupied. On 1 July, the new leader of the Mudan tribe and the chief of Kuskus admitted defeat and promised not to harm shipwrecked castaways.[110] Surrendered aborigines were given Japanese flags to fly over their villages. They were viewed as a symbol of peace with Japan and protection from rival tribes by the aborigines. To the Japanese, it was a symbol of jurisdiction over the aborigines.[111] Chinese forces arrived on 17 June and a report by Fujian Administration Commissioner reported that all 56 representatives of the tribes except for Mudan, Zhongshe and Linai, who were not present due to fleeing from the Japanese, complained about Japanese bullying.[112]

A Chinese representative, Pan Wei, met with Saigō four times between 22 and 26 June but nothing came of it. The Japanese settled in and established large camps with no intention of withdrawing, but in August and September 600 soldiers fell ill. They started dying 15 a day. The death toll rose to 561. Toshimichi Okubo arrived in Beijing on 10 September and seven negotiating sessions occurred over a month long period. The Western Powers pressured China not to cause bloodshed with Japan as it would negatively impact the coastal trade. The resulting Peking Agreement was signed on 30 October. Japan gained the recognition of Ryukyu as its vassal and an indemnity payment of 500,000 taels. Japanese troops withdrew from Taiwan on 3 December.[113]

Sino-French War

[edit]

During the Sino-French War, the French invaded Taiwan during the Keelung Campaign in 1884. The Chinese had already been aware of French plans to attack Taiwan and sent Liu Mingchuan, the governor of Fujian, to strengthen Taiwan's defenses on 16 July. On 5 August 1884, Sébastien Lespès bombarded Keelung's harbor and destroyed the gun placements. The next day, the French attempted to take Keelung but failed to defeat the larger Chinese force led by Liu Mingchuan and were forced to withdraw to their ships. On 1 October, Amédée Courbet landed with 2,250 French forces and defeated a smaller Chinese force, though equipped with Krupp guns, capturing Keelung. French efforts to capture Tamsui failed. The port of Tamsui had been filled with debris by the Chinese and the French were unable to sustain a landing. The French shelled Tamsui, destroying not only the forts but also foreign buildings. Some 800 French troops landed on Shalin beach near Tamsui but they were repelled by Chinese forces.[114]

The French imposed a blockade on Taiwan from 23 October 1884 until April 1885 but the execution was not completely effective. Foreign vessels were barred from docking in blockaded harbors. Some believed that the blockade was almost directed at the British. The French did not have enough ships to impose a complete blockade on Taiwan and only concentrated on the major ports, leaving smaller Chinese vessels to enter lesser ports with troops and supplies. The first Chinese relief effort, a fleet of five ships, was repelled by the French with two ships sunk. On 21 December 1884, five battalions in southern China were ordered to reinforce Taiwan.[115] French ships around mainland China's coast attacked any junk they could find and captured its occupants to be shipped to Keelung for constructing defensive works. However the blockade failed to stop Chinese junks from reaching Taiwan. For every junk the French captured, another five junks arrived with supplies at Takau and Anping. The immediate effect of the blockade was a sharp decline in legal trade and income.[116]

In late January 1885, Chinese forces suffered a serious defeat around Keelung. Although the French captured Keelung they were unable to move beyond its perimeters. In March the French tried to take Tamsui again and failed. At sea, the French bombarded Penghu on 28 March.[117] Penghu surrendered on 31 March but many of the French soon grew ill and 1,100 soldiers and later 600 more were debilitated. The French commander died from illness in Penghu.[118]

An agreement was reached on 15 April 1885 and an end to hostilities was announced. The French evacuation from Keelung was completed on 21 June 1885 and Penghu remained under Chinese control.[119]

End of Qing rule

[edit]

By the end of Qing rule in 1895, Taiwan's population consisted of nearly three million Han Chinese, 98% of which were Hoklo (82%) and Hakka (16%).[120] The indigenous population by 1895 was estimated at around 200,000.[121]

As part of the settlement for losing the Sino-Japanese War, the Qing empire ceded the islands of Taiwan and Penghu to Japan on April 17, 1895, according to the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki. The loss of Taiwan would become a rallying point for the Chinese nationalist movement in the years that followed.[122] The pro-Qing officials and elements of the local gentry declared an independent Republic of Formosa in 1895 and attempted to forestall Japanese annexation by appealing to Western intervention, especially France and Britain, but failed to win international recognition. The Japanese spent the next twenty years fighting rebellions in Taiwan while encouraging Japanese colonists to settle there. However, due to lack of infrastructure and fear of disease such as leprosy and malaria, few moved to Taiwan in the early years.[123] Between 200,000 and 300,000 people fled Taiwan during the Japanese invasion.[124][25] Chinese residents in Taiwan were given the option of selling their property and leaving by May 1897, or become Japanese citizens. From 1895 to 1897, an estimated 6,400 people sold their property and left Taiwan.[125][126]

Resistance against Japanese occupation

[edit]While the government deliberated on assimilation policies in Tokyo, the colonial authorities encountered violent opposition in much of Taiwan. Five months of sustained warfare occurred after the invasion of Taiwan in 1895 and partisan attacks continued until 1902. For the first two years the colonial authority relied mainly on military force and local pacification efforts. Disorder and panic were prevalent in Taiwan after Penghu was seized by Japan in March 1895. On 20 May, Qing officials were ordered to leave their posts. General mayhem and destruction ensued in the following months.[127]

Japanese forces landed on the coast of Keelung on 29 May and Tamsui's harbor was bombarded. Remnant Qing units and Guangdong irregulars briefly fought against Japanese forces in the north. After the fall of Taipei on 7 June, local militia and partisan bands continued the resistance. In the south, a small Black Flag force led by Liu Yongfu delayed Japanese landings. Governor Tang Jingsong attempted to carry out anti-Japanese resistance efforts as the Republic of Formosa, however he still professed to be a Qing loyalist. The declaration of a republic was, according to Tang, to delay the Japanese so that Western powers such as Great Britain or France might be compelled to defend Taiwan.[127] The plan quickly turned to chaos as the Green Standard Army and Yue soldiers from Guangxi took to looting and pillaging Taiwan. Given the choice between chaos at the hands of bandits or submission to the Japanese, Taipei's gentry elite sent Koo Hsien-jung to Keelung to invite the advancing Japanese forces to proceed to Taipei and restore order.[128] The Republic, established on 25 May, disappeared 12 days later when its leaders left for the mainland.[127] Liu Yongfu formed a temporary government in Tainan but escaped to the mainland as well as Japanese forces closed in.[129] From 1895 to 1897, an estimated 6,400 people, mostly gentry elites, left Taiwan.[125]

Upon Tainan's surrender, Kabayama declared Taiwan pacified, however his proclamation was premature. Armed resistance by Hakka villagers broke out in the south. A series of prolonged partisan attacks, led by "local bandits" or "rebels", lasted throughout the next seven years. After 1897, uprisings by Chinese nationalists were commonplace. Luo Fuxing, a member of the Tongmenghui organization preceding the Kuomintang, was arrested and executed along with two hundred of his comrades in 1913.[130] Japanese reprisals were often more brutal than the guerilla attacks staged by the rebels. In June 1896, 6,000 Taiwanese were slaughtered in the Yunlin Massacre. From 1898 to 1902, some 12,000 "bandit-rebels" were killed in addition to the 6,000–14,000 killed in the initial resistance war of 1895.[129][131] During the conflict, 5,300 Japanese were killed or wounded, and 27,000 were hospitalized.[132]

Rebellions were often caused by a combination of unequal colonial policies on local elites and extant millenarian beliefs of the local Taiwanese and plains Aborigines.[133] Ideologies of resistance drew on different ideals such as Taishō democracy, Chinese nationalism, and nascent Taiwanese self-determination.[122] Major armed resistance was largely crushed by 1902 but minor rebellions started occurring again in 1907, such as the Beipu uprising by Hakka and Saisiyat people in 1907, Luo Fuxing in 1913 and the Tapani Incident of 1915.[133][134] The Beipu uprising occurred on 14 November 1907 when a group of Hakka insurgents killed 57 Japanese officers and members of their family. In the following reprisal, 100 Hakka men and boys were killed in the village of Neidaping.[135] Luo Fuxing was an overseas Taiwanese Hakka involved with the Tongmenghui. He planned to organize a rebellion against the Japanese with 500 fighters, resulting in the execution of more than 1,000 Taiwanese by Japanese police. Luo was killed on 3 March 1914.[131][136] In 1915, Yu Qingfang organized a religious group that openly challenged Japanese authority. In what is known as the Tapani incident, 1,413 members of Yu's religious group were captured. Yu and 200 of his followers were executed.[137]

List of governors

[edit]

| No. | Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Ancestry | Previous post | Term of office (Chinese calendar) |

Emperor of the Qing dynasty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

Liu Mingchuan 劉銘傳 Liú Míngchuán (Mandarin) Lâu Bêng-thoân (Taiwanese) Liù Mèn-chhòn (Hakka) (1836–1896) |

Hefei, Anhui | Governor of Fujian | 12 October 1885 Guangxu 11-9-5 |

4 June 1891 Guangxu 17-4-28 |

|

| acting |

|

Shen Yingkui 沈應奎 Shěn Yìngkuí (Mandarin) Sím Èng-khe (Taiwanese) Sṳ́m En-khùi (Hakka) |

Pinghu, Zhejiang | Civil Affairs Minister, Fujian-Taiwan Province | 4 June 1891 Guangxu 17-4-28 |

25 November 1891 Guangxu 17-10-24 | |

| 2 |

|

Shao Youlian 邵友濂 Shào Yǒulián (Mandarin) Siō Iú-liâm (Taiwanese) Seu Yû-liàm (Hakka) (1840–1901) |

Yuyao, Zhejiang | Governor of Hunan | 9 May 1891 Guangxu 17-4-2 |

13 October 1894 Guangxu 20-9-15 | |

| 3 |

|

Tang Jingsong 唐景崧 Táng Jǐngsōng (Mandarin) Tn̂g Kéng-siông (Taiwanese) Thòng Kín-chhiùng (Hakka) (1841–1903) |

Guanyang, Guangxi | Civil Affairs Minister, Fujian-Taiwan Province | 13 October 1894 Guangxu 20-9-15 |

20 May 1895 Guangxu 21-4-26 | |

See also

[edit]- Han Taiwanese

- Qing Dynasty Taiwan Provincial Administration Hall

- Taiwanese aborigines: Qing rule

- Tai Chao-chuen incident

- Manchuria under Qing rule

- Mongolia under Qing rule

- Xinjiang under Qing rule

- Tibet under Qing rule

- Taiwan under Japanese rule

- History of Taiwan

Notes

[edit]- ^ Tangshan means "Chinese".

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Taiwan in Time: The admiral's secret plan – Taipei Times". 23 September 2018. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ 臺灣歷史地圖 增訂版 [Taiwan Historical Maps, Expanded and Revised Edition]. Taipei: National Museum of Taiwan History. February 2018. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-986-05-5274-4.

- ^ "清代臺灣行政區劃沿革". Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Wong 2017, p. 179–180.

- ^ Wong 2017, p. 183–184.

- ^ Wong 2017, p. 184.

- ^ a b Wong 2017, p. 187.

- ^ Teng (2004), pp. 34–59.

- ^ Wong 2017, p. 187–188.

- ^ Teng (2004), pp. 34–49, 177–179.

- ^ Wong 2017, p. 189–190.

- ^ Twitchett 2002, p. 146.

- ^ Thompson 1964, p. 178–179.

- ^ Thompson 1964, p. 180.

- ^ Thompson 1964, p. 183.

- ^ Thompson 1964, p. 180–181.

- ^ Thompson 1964, p. 181.

- ^ Thompson 1964, p. 181–182.

- ^ a b Thompson 1964, p. 182.

- ^ Thompson 1964, p. 182–183.

- ^ "清代臺灣行政區劃沿革". Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Wong 2017, p. 193.

- ^ a b c d Wong 2017, p. 194.

- ^ Stafford, Charles; Shepherd, John Robert (September 1994). "Statecraft and Political Economy on the Taiwan Frontier 1600–1800". Man. 29 (3): 750. doi:10.2307/2804394. ISSN 0025-1496. JSTOR 2804394.

- ^ a b Davidson (1903), p. 561.

- ^ a b Ye 2019, p. 51.

- ^ "Entry #60161". 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 [Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan]. (in Chinese and Hokkien). Ministry of Education, R.O.C. 2011.

- ^ Tai, Pao-tsun (2007). The Concise History of Taiwan (Chinese-English bilingual ed.). Nantou City: Taiwan Historica. p. 52. ISBN 9789860109504.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Ye 2019, p. 54.

- ^ a b Shepherd 1993, p. 150–154.

- ^ a b Ye 2019, p. 50–55.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 52, 55, 71.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 46–47.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 47–49.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 49.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 49–50.

- ^ Andrade 2008f.

- ^ Andrade 2008h.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 21.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Rubinstein 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d Rubinstein 1999, p. 136.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 34.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 57.

- ^ a b Rubinstein 1999, p. 177.

- ^ Rubinstein 1999, p. 331.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 13.

- ^ Li 2019, p. 5.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 55–56.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 56.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 56–57.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 58.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 59–60.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 60–61.

- ^ Rubinstein 1999, p. 126.

- ^ A jia is equal to 0.97 hectares

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 61–62.

- ^ Chiu, Hungdah (1979). China and the Taiwan Issue. London: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-03-048911-3.

- ^ Paine, S.C.M (2002). The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81714-5.

- ^ Ravina, Mark (2003). The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-08970-2.

- ^ Smits, Gregory (1999). "Visions of Ryūkyū: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics." Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- ^ a b Ye 2019, p. 62.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 63–64.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 64–65.

- ^ Rubinstein 1999, p. 187–190.

- ^ "清代臺灣行政區劃沿革". Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b Rubinstein 1999, p. 191.

- ^ a b Ye 2019, p. 65.

- ^ Cheung, Han (2 May 2021). "Taiwan in Time: The fall of the northern Atayal". www.taipeitimes.com. Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 1, 10, 174.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 1.

- ^ Ye 2019, pp. 174–175, 166.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 63.

- ^ a b Twitchett 2002, p. 228.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 91.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 106.

- ^ van der Wees, Gerrit. "Has Taiwan Always Been Part of China?". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Skoggard, Ian A. (1996). The Indigenous Dynamic in Taiwan's Postwar Development: The Religious and Historical Roots of Entrepreneurship. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9781563248467. OL 979742M. p. 10

- ^ 民變 [Civil Strife]. Encyclopedia of Taiwan (台灣大百科). Taiwan Ministry of Culture. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021. 臺灣有「三年一小反,五年一大反」之謠。但是根據研究,這句俗諺所形容民變迭起的現象,以道光朝(1820-1850)的三十多年間為主 [The rumor of "every three years a small uprising, five years a large rebellion" circulated around Taiwan. According to research, the repeated commotions described by this idiom occurred primarily during the 30-year period between 1820 and 1850.].

- ^ a b c d e "Taiwan in Time: Rebels of heaven and earth – Taipei Times". 17 April 2016. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b Li 2019, p. 82–83.

- ^ a b c Standaert 2022, p. 225.

- ^ Li 2019, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d e Cheung, Han. "Taiwan in Time: A blood-soaked 16 days in Yilan". www.taipeitimes.com. Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Inkster 2010, p. 35–36.

- ^ Inkster 2010, p. 36.

- ^ a b Shih-Shan Henry Tsai (2009). Maritime Taiwan: Historical Encounters with the East and the West. Routledge. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-317-46517-1. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ Leonard H. D. Gordon (2007). Confrontation Over Taiwan: Nineteenth-Century China and the Powers. Lexington Books. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7391-1869-6. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ Elliott 2002, p. 197.

- ^ Barclay 2018, p. 56.

- ^ Wong 2022, p. 119.

- ^ Wong 2022, p. 119–120.

- ^ Wong 2022, p. 121–122.

- ^ Wong 2022, p. 123.

- ^ Barclay 2018, p. 50.

- ^ Barclay 2018, p. 51–52.

- ^ Barclay 2018, p. 52.

- ^ Barclay 2018, p. 53–54.

- ^ Wong 2022, p. 124–126.

- ^ a b Wong 2022, p. 127–128.

- ^ Leung (1983), p. 270.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 185–186.

- ^ Ye 2019, p. 187.

- ^ Wong 2022, p. 129.

- ^ Wong 2022, p. 132.

- ^ Wong 2022, p. 130.

- ^ Wong 2022, p. 134–137.

- ^ Wong 2022, p. 137–138.

- ^ "| of Civilization and Savages: The Mimetic Imperialism of Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan | the American Historical Review, 107.2 | the History Cooperative". Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ Wong 2022, p. 138.

- ^ Wong 2022, p. 141–143.

- ^ Gordon 2007, p. 142–145.

- ^ Gordon 2007, p. 146–49.

- ^ Gordon 2007, p. 149–151, 154.

- ^ Gordon 2007, p. 149–151.

- ^ Gordon 2007, p. 161–162.

- ^ Gordon 2007, p. 162.

- ^ Lamley, Harry J. (1981). Emily Martin; Hill Gates (eds.). "The Anthropology of Taiwanese Society: Chapter 11. Subethnic Rivalry in the Ch'ing Period" (PDF). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Davidson (1903), p. 563.

- ^ a b Zhang (1998), p. 514.

- ^ Matsuda 2019, p. 103–104.

- ^ Wang 2006, p. 95.

- ^ a b Rubinstein 1999, p. 208.

- ^ Brooks 2000, p. 110.

- ^ a b c Rubinstein 1999, p. 205–206.

- ^ Morris (2002), pp. 4–18.

- ^ a b Rubinstein 1999, p. 207.

- ^ Zhang (1998), p. 515.

- ^ a b Chang 2003, p. 56.

- ^ Rubinstein 1999, p. 207–208.

- ^ a b Katz (2005).

- ^ Huang-wen lai (2015). "The turtle woman's voices: Multilingual strategies of resistance and assimilation in Taiwan under Japanese colonial rule" (pdf published=2007). p. 113. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ Lesser Dragons: Minority Peoples of China. Reaktion Books. 15 May 2018. ISBN 9781780239521. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Place and Spirit in Taiwan: Tudi Gong in the Stories, Strategies and Memories of Everyday Life. Routledge. 29 August 2003. ISBN 9781135790394. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Tsai 2009, p. 134.

Sources

[edit]- Andrade, Tonio (2008a), "Chapter 1: Taiwan on the Eve of Colonization", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 24 February 2021, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2008b), "Chapter 2: A Scramble for Influence", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 27 September 2022, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2008c), "Chapter 3: Pax Hollandica", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 28 September 2022, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2008d), "Chapter 4: La Isla Hermosa: The Rise of the Spanish Colony in Northern Taiwan", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 3 March 2016, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2008e), "Chapter 5: The Fall of Spanish Taiwan", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 29 September 2022, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2008f), "Chapter 6: The Birth of Co-colonization", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 9 August 2022, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2008g), "Chapter 7: The Challenges of a Chinese Frontier", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 29 September 2022, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2008h), "Chapter 8: "The Only Bees on Formosa That Give Honey"", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 29 September 2022, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2008i), "Chapter 9: Lord and Vassal: Company Rule over the Aborigines", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 28 September 2022, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2008j), "Chapter 10: The Beginning of the End", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 29 September 2022, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2008k), "Chapter 11: The Fall of Dutch Taiwan", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 19 April 2021, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2008l), "Conclusion", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 2 April 2018, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2011a), Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China's First Great Victory Over the West (illustrated ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691144559, archived from the original on 10 April 2023, retrieved 27 September 2022

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7

- Barclay, Paul D. (2018), Outcasts of Empire: Japan's Rule on Taiwan's "Savage Border," 1874-1945, University of California Press

- Bellwood, Peter; Hung, Hsiao-Chun; Iizuka, Yoshiyuki (2011), "Taiwan Jade in the Philippines: 3,000 Years of Trade and Long-distance Interaction" (PDF), in Benitez-Johannot, Purissima (ed.), Paths of Origins: The Austronesian Heritage in the Collections of the National Museum of the Philippines, the Museum Nasional Indonesia, and the Netherlands Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Singapore: ArtPostAsia, pp. 31–41, hdl:1885/32545, ISBN 9789719429203, archived (PDF) from the original on 12 August 2022, retrieved 27 September 2022.

- Bird, Michael I.; Hope, Geoffrey; Taylor, David (2004), "Populating PEP II: the dispersal of humans and agriculture through Austral-Asia and Oceania" (PDF), Quaternary International, 118–119: 145–163, Bibcode:2004QuInt.118..145B, doi:10.1016/s1040-6182(03)00135-6, archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2014, retrieved 12 April 2007.

- Blusse, Leonard; Everts, Natalie (2000), The Formosan Encounter: Notes on Formosa's Aboriginal Society – A selection of Documents from Dutch Archival Sources Vol. I & II, Taipei: Shung Ye Museum of Formosan Aborigines, ISBN 957-99767-2-4 and ISBN 957-99767-7-5.