Golan Heights

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (October 2024) |

Golan Heights

هَضْبَةٌ الجَوْلَان רָמַת הַגּוֹלָן | |

|---|---|

Location of the Golan Heights | |

| Coordinates: 33°00′N 35°45′E / 33.000°N 35.750°E | |

| Status | Syrian territory, occupied by Israel[1][2][a][b] |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,800 km2 (700 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 2,814 m (9,232 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | −212 m (−696 ft) |

| Population | |

• Total | ~55,000 |

| • Arabs (nearly all Druze) | ~24,000 |

| • Israeli Jewish settlers | ~31,000 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 |

The Golan Heights,[c] or simply the Golan, is a basaltic plateau at the southwest corner of Syria. It is bordered by the Yarmouk River in the south, the Sea of Galilee and Hula Valley in the west, the Anti-Lebanon mountains with Mount Hermon in the north and Wadi Raqqad in the east. It hosts vital water sources that feed the Hasbani River and the Jordan River.[5] Two thirds of the area was occupied by Israel following the 1967 Six-Day War and then effectively annexed in 1981 – an action unrecognized by the international community, which continues to consider it Israeli-occupied Syrian territory. In 2024 Israel occupied the remaining one third of the area.

The earliest evidence of human habitation on the Golan dates to the Upper Paleolithic period.[6] It was home to the biblical Geshur, and was later incorporated into Aram-Damascus,[7][8] before being ruled by several foreign and domestic powers, including the Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians,[9][10] Itureans, Hasmoneans, Romans,[11][12][13] Ghassanids, several caliphates, and the Mamluk Sultanate. It was ruled by the Ottoman Empire from the 16th century until its collapse,[14][15] and subsequently became part of the French Mandate in Syria and the State of Damascus in 1923.[16] When the mandate terminated in 1946, it became part of the newly independent Syrian Arab Republic, spanning about 1,800 km2 (690 sq mi).

After the Six-Day War of 1967, the Golan Heights were occupied and administered by Israel.[1][2] Following the war, Syria dismissed any negotiations with Israel as part of the Khartoum Resolution at the 1967 Arab League summit.[17] Civil administration of a third of the Golan heights, including the capital Quneitra, was restored to Syria in a disengagement agreement the year after the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Construction of Israeli settlements began in the territory held by Israel, which was under a military administration until the Knesset passed the Golan Heights Law in 1981, which applied Israeli law to the territory;[18] this move has been described as an annexation and was condemned by the United Nations Security Council in Resolution 497.[d][2]

After the onset of the Syrian civil war in 2011, control of the Syrian-administered part of the Golan Heights was split between the state government and Syrian opposition forces, with the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) maintaining a 266 km2 (103 sq mi) buffer zone in between to help implement the Israeli–Syrian ceasefire across the Purple Line.[20] From 2012 to 2018, the eastern half of the Golan Heights became a scene of repeated battles between the Syrian Army, rebel factions of the Syrian opposition (including the Southern Front) as well as various jihadist organizations such as al-Nusra Front and the Khalid ibn al-Walid Army. In July 2018, the Syrian government regained full control over the eastern Golan Heights.[21] After the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024, Israel occupied the rest of the Golan Heights as a "temporary defensive position",[22] followed by two additional Syrian villages, Jamlah and Maaraba.[23]

Etymology

In the Bible, Golan is mentioned as a city of refuge located in Bashan: Deuteronomy 4:43, Joshua 20:8 and 1 Chronicles 6:71.[24] Nineteenth-century authors interpreted the word Golan as meaning "something surrounded, hence a district".[25][26] The shift in the meaning of Golan, from a town to a broader district or territory, is first attested by the Jewish historian Josephus. His account likely reflects Roman administrative changes implemented after the Great Jewish Revolt (66–73 CE).[27]

The Greek name for the region is Gaulanîtis (Γαυλανῖτις).[28] In the Mishnah the name is Gablān similar to Aramaic language names for the region: Gawlāna, Guwlana and Gublānā.[28]

The Arabic name is Jawlān,[28] sometimes romanized as Djolan, which is an Arabized version of the Canaanite and Hebrew name.[29] Arab cartographers of the Byzantine period referred to the area as jabal (جَبَل, 'mountain'), though the region is a plateau.[30][dubious – discuss]

The name Golan Heights was not used before the 19th century.[24]

History

Early history

The Venus of Berekhat Ram, a pebble from the Lower Paleolithic era found in the Golan Heights, may have been carved by Homo erectus between 700,000 and 230,000 BC.[31]

The southern Golan saw a rise in settlements from the 2nd millennium BCE onwards. These were small settlements located on the slopes overlooking the Sea of Galilee or nearby gorges. They may correspond to the "cities of the Land of Ga[šu]ru'" mentioned in Amarna Letter #256.5, written by the prince of Pihilu (Pella). This suggests a different form of political organization compared to the prevalent city-states of the region, such as Hatzor to the west and Ashteroth to the east.[32] During the Late Bronze Age, the Golan was only sparsely inhabited.[33]

Following the Late Bronze Age collapse, the Golan was home to the newly formed kingdom of Geshur,[34] likely a continuation of the earlier "Land of Ga[šu]ru".[32][33] The Hebrew Bible mentions it as a distinct entity during the reign of David (10th century BC). David's marriage to Maacha, daughter of King Talmai of Geshur, supports a dynastic alliance with Israel.[32] However, by the mid-9th century BC, Aram-Damascus absorbed Geshur into its expanding territory.[34][32][35] Aram-Damascus' rivalry with the Kingdom of Israel led to numerous military clashes in the Golan and Gilead regions throughout the 9th and 8th centuries BC. The Bible recounts two Israelite victories at Aphek, a location possibly corresponding to the modern-day Afik, near the Sea of Galilee.[32]

During the 8th century BC, the Assyrians conquered the region, incorporating it into the province of Qarnayim, likely including Damascus as well.[33] This period was succeeded by the Babylonian and the Achaemenid Empire. In the 5th century BC, the Achaemenid Empire allowed the region to be resettled by returning Jewish exiles from the Babylonian Captivity, a fact that has been noted in the Mosaic of Rehob.[9][10][8]

After the Assyrian period, about four centuries provide limited archaeological finds in the Golan.[36]

Hellenistic and early Roman periods

The Golan Heights, along with the rest of the region, came under the control of Alexander the Great in 332 BC, following the Battle of Issus. Following Alexander's death, the Golan came under the domination of the Macedonian general Seleucus and remained part of the Seleucid Empire for most of the next two centuries.[37] In the middle of the 2nd century BC, Itureans moved into the Golan,[38] occupying over one hundred locations in the region.[39] Iturean stones and pottery have been found in the area.[40] Itureans also built several temples, one of them in function up until the Islamic conquest.[41]

Around 83–81 BC, the Golan was captured by the Hasmonean king and high priest Alexander Jannaeus, annexing the area to the Hasmonean kingdom of Judaea.[42] Following this conquest, the Hasmoneans encouraged Jewish migrants from Judea to settle in the Golan.[43] Most scholars agree that this settlement began after the Hasmonean conquest, though it might have started earlier,[13] probably in the mid-2nd century BC.[44] Over the next century, Jewish settlement in the Golan and nearby regions became widespread, reaching north to Damascus and east to Naveh.[42]

When Herod the Great ascended to power in Judaea during the latter half of the first century BC, the region as far as Trachonitis, Batanea and Auranitis was put under his control by Augustus Caesar.[45] Following the death of Herod the Great in 4 BC, Augustus Caesar adjudicated that the Golan fell within the Tetrarchy of Herod's son, Herod Philip I.[43] The capital of Jewish Galaunitis, Gamla, was a prominent city and major stronghold.[46] It housed one of the earliest known synagogues, believed to have been constructed in the late 1st century BC, when the Temple in Jerusalem was still standing.[47][48]

After Philip's death in 34 AD, the Romans absorbed the Golan into the province of Syria, but Caligula restored the territory to Herod's grandson Agrippa in 37. Following Agrippa's death in 44, the Romans again annexed the Golan to Syria, promptly to return it again when Claudius traded the Golan to Agrippa II, the son of Agrippa I, in 51 as part of a land swap.[citation needed]

By the time of the Great Jewish revolt, which began in 66 AD, parts of the Golan Heights were predominantly inhabited by Jews. Josephus depicts the western and central Golan as densely populated with cities that emerged on fertile stony soil.[42] Despite nominally being under Agrippa's control and situated outside the province of Judaea, the Jewish communities in the area participated in the revolt. Initially, Gamla was loyal to Rome, but later the town switched allegiance and even minted its own revolt coins.[44][49] Josephus, who was appointed by the provisional government in Jerusalem as commander of Galilee, fortified the cities of Sogana, Seleucia, and Gamla in the Golan.[49][42] The Roman military, under Vespasian's command, eventually ended the northern revolt in 67 AD by capturing Gamla after a siege. Josephus reports that the people of Gamla opted for mass suicide, throwing themselves into a ravine.[42] Today, the visible breach in the wall near the synagogue, along with remnants such as fortress walls, tower ruins, armor fragments, various projectiles, and fire damage, testify to the siege's intensity.[44]

Following the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD, many Jews fled north to Galilee and the Golan, further increasing the Jewish population in the region.[42] Another notable surge in Jewish migration to the Golan took place in the aftermath of the Bar Kokhba revolt, c. 135 AD.[42] During this time, Jews remained a minority of the population in the Golan.[50]

Late Roman and Byzantine periods

In the later Roman and Byzantine periods, the area was administered as part of Phoenicia Prima and Syria Palaestina, and finally Golan/Gaulanitis was included together with Peraea[30] in Palaestina Secunda, after 218 AD.[51] The area of the ancient kingdom of Bashan was incorporated into the province of Batanea.[52] By the close of the second century, Judah ha-Nasi was granted a lease for 2,000 units of land in the Golan.[53] An excavation held at Hippos has recently discovered an unknown Roman road that connected the Sea of Galilee with the city of Nawa in Syria.[54]

The political and economic recovery of Palestine during the reigns of Diocletian and Constantine, in the late 3rd and early 4th centuries AD, led to a resurgence of Jewish life in the Golan. Excavations at various synagogue sites have uncovered ceramics and coins that provide evidence of this resettlement.[55] During this period, several synagogues were constructed, and today 25 locations with ancient synagogues or their remnants have been discovered, all situated in the central Golan. These synagogues, built from the abundant basalt stones of the region, were influenced by those in the Galilee but exhibited their own distinctive characteristics; prominent examples include Umm el-Qanatir, Qatzrin and Deir Aziz.[55] Some of the early Jerusalem Talmud tractates may have been arranged and edited during this period in Qatzrin.[56][53] Several sites in the Golan show evidence of destruction from the Jewish revolt against Gallus in 351 CE. However, some of these sites were later rebuilt and continued to be inhabited in subsequent centuries.[53]

In the 5th century, the Byzantine Empire assigned the Ghassanids, a Christian Arab tribe that had settled in Syria, the task of protecting its eastern borders against the Sasanian-allied Arab tribe, the Lakhmids.[57] The Ghassanids had emigrated from Yemen in the third century and actively supported Byzantium against Persia.[58] They were initially nomadic but gradually became semi-sedentary,[57] and adopted Christianity along with a number of Arab tribes situated in the borders of the Byzantine Empire in the 3rd and 4th centuries.[59] The Ghassanids had adopted Monophysitism in the 5th century.[60] At the end of the 5th century, the primary Ghassanid encampments in the Golan were Jabiyah and Jawlan, situated in the eastern Golan beyond the Ruqqad.[61][62][57] The Ghassanids settled deep inside the Byzantine limes, and in a Syriac source for July 519, they are attested as having their "opulent" headquarters in the eastern Gaulanitis.[63] Like the Herodian dynasty before them, the Ghassanids ruled as a client state of Rome – this time, the Christianized Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantium. In 529, Emperor Justinian appointed al-Harith ibn Jabalah as Phylarch, making him the leader of all Arab tribes and bestowing upon him the title of Patricius, ranking just below the Emperor.[57]

Christians and Arabs became the majority in the Golan with the arrival of the Ghassanids to the region.[64] In 377 CE, a sanctuary for John the Baptist was established in the Golan village of Er-Ramthaniyye.[65] The sanctuary was often visited by the Ghassanids.[66]

In the 6th century, the Golan was inhabited by the well-established Jews and Ghassanid Christians.[60][67] The Jewish population in the Golan engaged in agriculture, as evidenced by pre-Islamic Arab poet Muraqquish the Younger, who mentioned wine brought by Jewish traders from the region,[68] and local synagogues may have been funded by the prosperous production of olive oil.[69] A monastery and church dedicated to Saint George has been found in the Byzantine village of Deir Qeruh in the Golan, located near Gamla. The church has a square apse - a feature known from ancient Syria and Jordan, but not present in churches west of the Jordan River.[70]

The Ghassanids were able to hold on to the Golan until the Sassanid invasion of 614. Following a brief restoration under the Emperor Heraclius, the Golan again fell, this time to the invading Muslim Arabs after the Battle of Yarmouk in 636.[71] Data from surveys and excavations combined show that the bulk of sites in the Golan were abandoned between the late 6th and early 7th century as a result of military incursions, the breakdown of law and order, and the economy brought on by the weakening of the Byzantine rule. Some settlements lasted till the end of the Umayyad era.[72]

Early Muslim period

After the Battle of Yarmouk, Muawiyah I, a member of Muhammad's tribe, the Quraish, was appointed governor of Syria, including the Golan. Following the assassination of his cousin, the Caliph Uthman, Muawiya claimed the Caliphate for himself, initiating the Umayyad dynasty. Over the next few centuries, while remaining in Muslim hands, the Golan passed through many dynastic changes, falling first to the Abbasids, then to the Shi'ite Fatimids, then to the Seljuk Turks.[citation needed]

An earthquake devastated the Jewish village of Katzrin in 746 AD. Following it, there was a brief period of greatly diminished occupation during the Abbasid period (approximately 750–878). Jewish communities persisted at least into the Middle Ages in the towns of Fiq in the southern Golan and Nawa in Batanaea.[73]

For many centuries nomadic tribes lived together with the sedentary population in the region. At times, the central government attempted to settle the nomads which would result in the establishment of permanent communities. When the power of the governing regime declined, as happened during the early Muslim period, nomadic trends increased and many of the rural agricultural villages were abandoned due to harassment from the Bedouins. They were not resettled until the second half of the 19th century.[74]

Crusader/Ayyubid period

During the Crusades, the Golan represented an obstacle to the Crusader armies,[75][76] who nevertheless held the strategically important town of Banias twice, in 1128–32 and 1140–64.[77] After victories by Sultan Nur ad-Din Zangi, it was the Kurdish dynasty of the Ayyubids under Sultan Saladin who ruled the area. The Mongols swept through in 1259, but were driven off by the Mamluk commander and future sultan Qutuz at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260.[citation needed]

The victory at Ain Jalut ensured Mamluk dominance of the region for the next 250 years.[citation needed]

Ottoman period

In the 16th century, the Ottoman Turks conquered Syria. During this time, the Golan formed part of the Hauran Sanjak. Some Druze communities were established in the Golan during the 17th and 18th centuries.[79] The villages abandoned during previous periods due to raids by Bedouin tribes were not resettled until the second half of the 19th century.[74] Throughout the 18th century, the Al Fadl, an Arab tribe long established in the Levant, struggled against Turkmen and Kurdish tribesmen over supremacy in the Golan.[80] The Fadl's presence in the Golan was observed by Burckhardt in the early 19th century.[81]

In 1868, the region was described as "almost entirely desolate". According to a travel handbook of the time, only 11 of 127 ancient towns and villages in the Golan were inhabited.[82] By the late 19th century, the Golan Heights was mostly inhabited by Arabs, Turkmen and Circassians.[83] The Circassians, part of a large influx of refugees from the Caucasus into the empire as a result of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, were encouraged to settle in the Golan by the Ottoman authorities. They were granted lands with a 12-year tax exemption.[84][85][86] The Al Fadl, the Druze and the Circassians were often in conflict for local dominance. These struggles subsided with the Ottoman government's formal recognition of the Al Fadl's tribal territory and pasturelands in the Golan, which were invested in the name of the tribe's emir. The emir relocated to Damascus and collected rents from his tribesmen who thereafter settled in the area and engaged in a combination of farming and pastoralism.[80] The tribe settled in several villages in the area and controlled important roads to Damascus, Galilee and Lebanon.[87] In the 19th century the tribe continued to expand their territory in the Golan and built two palaces.[87] The leader of the tribe joined Prince Faisal during the Arab revolt,[88] and they supported the uprising against the French in the northern Golan.[88]

In 1885, civil engineer and architect, Gottlieb Schumacher, conducted a survey of the entire Golan Heights on behalf of the German Society for the Exploration of the Holy Land, publishing his findings in a map and book entitled The Jaulân.[89][90]

Early Jewish settlement

In 1880, Laurence Oliphant published Eretz ha-Gilad (The Land of Gilead), which described a plan for large-scale Jewish settlement in the Golan.[91] In 1884, there were still open stretches of uncultivated land between villages in the lower Golan, but by the mid-1890s most were owned and cultivated.[92] Some land had been purchased in the Golan and Hawran by Zionist associations based in Romania, Bulgaria, the United States and England, in the late 19th century and early 20th century.[93] In the winter of 1885, members of the Old Yishuv in Safed formed the Beit Yehuda Society and purchased 15,000 dunams of land from the village of Ramthaniye in the central Golan.[94] Due to financial hardships and the long wait for a kushan (Ottoman land deed) the village, Golan be-Bashan, was abandoned after a year.[citation needed]

Soon afterwards, the society regrouped and purchased 2,000 dunams of land from the village of Bir e-Shagum on the western slopes of the Golan.[95] The village they established, Bnei Yehuda, existed until 1920.[96][97] The last families left in the wake of the Passover riots of 1920.[94] In 1944 the JNF bought the Bnei Yehuda lands from their Jewish owners, but a later attempt to establish Jewish ownership of the property in Bir e-Shagum through the courts was not successful.[96]

Between 1891 and 1894, Baron Edmond James de Rothschild purchased around 150,000 Dunams of land in the Golan and the Hawran for Jewish settlement.[94] Legal and political permits were secured and ownership of the land was registered in late 1894.[94] The Jews also built a road stretching from Lake Hula to Muzayrib.[96] The Agudat Ahim society, whose headquarters were in Yekaterinoslav, Russia, acquired 100,000 dunams of land in several locations in the districts of Fiq and Daraa. A plant nursery was established and work began on farm buildings in Jillin.[94] A village called Tiferet Binyamin was established on lands purchased from Saham al-Jawlan by the Shavei Zion Association based in New York,[93] but the project was abandoned after a year when the Turks issued an edict in 1896 evicting the 17 non-Turkish families. A later attempt to resettle the site with Syrian Jews who were Ottoman citizens also failed.[98]

Between 1904 and 1908, a group of Crimean Jews settled near the Arab village of al-Butayha in the Bethsaida Valley, initially as tenants of a Kurdish proprietor with the prospects of purchasing the land, but the arrangement faltered.[98][99] Jewish settlement in the region dwindled over time, due to Arab hostility, Turkish bureaucracy, disease and economic difficulties.[100] In 1921–1930, during the French Mandate, the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association (PICA) obtained the deeds to the Rothschild estate and continued to manage it, collecting rents from the Arab peasants living there.[96]

French and British mandates

Great Britain accepted a Mandate for Palestine at the meeting of the Allied Supreme Council at San Remo, but the borders of the territory were not defined at that stage.[101][102] The boundary between the forthcoming British and French mandates was defined in broad terms by the Franco-British Boundary Agreement of December 1920.[103] That agreement placed the bulk of the Golan Heights in the French sphere. The treaty also established a joint commission to settle the precise details of the border and mark it on the ground.[103]

The commission submitted its final report on 3 February 1922, and it was approved with some caveats by the British and French governments on 7 March 1923, several months before Britain and France assumed their Mandatory responsibilities on 29 September 1923.[104][105] In accordance with the same process, a nearby parcel of land that included the ancient site of Tel Dan and the Dan spring were transferred from Syria to Palestine early in 1924.

The Golan Heights, including the spring at Wazzani and the one at Banias, became part of French Syria, while the Sea of Galilee was placed entirely within British Mandatory Palestine. When the French Mandate for Syria ended in 1944, the Golan Heights became part of the newly independent state of Syria and was later incorporated into Quneitra Governorate.

Border incidents after 1948

After the 1948–49 Arab–Israeli War, the Golan Heights were partly demilitarized by the Israel-Syria Armistice Agreement. During the following years, the area along the border witnessed thousands of violent incidents; the armistice agreement was being violated by both sides. The underlying causes of the conflict were a disagreement over the legal status of the demilitarised zone (DMZ), cultivation of land within it and competition over water resources. Syria claimed that neither party had sovereignty over the DMZ.[106][107]

Israel contended that the Armistice Agreement dealt solely with military concerns and that it had political and legal rights over the DMZ. Israel wanted to assert control up till the 1923 boundary in order to claim the Hula swamp, gain exclusive rights to Lake Galilee and divert water from the Jordan for its National Water Carrier. During the 1950s, Syria registered two principal territorial accomplishments: it took over Al Hammah enclosure south of Lake Tiberias and established a de facto presence on and control of the eastern shore of the lake.[106][107]

Israel expelled Arabs from the DMZ and demolished their homes.[108] Palestinian refugees were denied the right of return or compensation, and because of this they started raids on Israel.[109] The Syrian government supported the Palestinian attacks because of Israel taking over more land in the DMZ.[109]

The Jordan Valley Unified Water Plan was sponsored by the United States and agreed by the technical experts of the Arab League and Israel.[110] The U.S. funded the Israeli and Jordanian water diversion projects, when they pledged to abide by the plan's allocations.[111] President Nasser too, assured the U.S. that the Arabs would not exceed the plan's water quotas.[112] However, in the early 1960s the Arab League funded a Syrian water diversion project that would have denied Israel use of a major portion of its water allocation.[113] The resulting armed clashes are called the War over Water.[114]

In 1955, Israel launched an attack that killed 56 Syrian soldiers. The attack was condemned by the United Nations Security Council.[115]

in July 1966,[116] Fatah began raids into Israeli territory, with active support from Syria. At first the militants entered via Lebanon or Jordan, but those countries made concerted attempts to stop them and raids directly from Syria increased.[117] Israel's response was a series of retaliatory raids, of which the largest were an attack on the Jordanian village of Samu in November 1966.[118] In April 1967, after Syria heavily shelled Israeli villages from the Golan Heights, Israel shot down six Syrian MiG fighter planes and warned Syria against future attacks.[117][119]

The Israelis used to send tractors with armed police into the DMZ, which prompted Syria firing at Israel.[115] In the period between the first Arab–Israeli War and the Six-Day War, the Syrians constantly harassed Israeli border communities by firing artillery shells from their dominant positions on the Golan Heights.[120] In October 1966 Israel brought the matter up before the United Nations. Five nations sponsored a resolution criticizing Syria for its actions but it failed to pass.[121][122] No Israeli civilian was killed in half a year leading up to the Six-Day War and the Syrian attacks have been called: "largely symbolic".[115]

Former Israeli General Mattityahu Peled said that more than half of the border clashes before the 1967 war "were a result of our security policy of maximum settlement in the demilitarised area".[123][better source needed] Israeli incursions into the zone were responded to with Syrians shooting. Israel in turn would retaliate with military force.[106] The narrative of Syrians attacking "innocent" Israel from the Golan Heights has been called "historical revisionism".[115]

In 1976, former Israeli defense minister Moshe Dayan said Israel provoked more than 80% of the clashes with Syria in the run up to the 1967 war, although two Israeli historians debate whether he was "giving an accurate account of the situation in 1967 or whether his version of what happened was colored by his disgrace after the 1973 Middle East war, when he was forced to resign as Defense Minister over the failure to anticipate the Arab attack."[124] The provocation was sending a tractor to plow in the demilitarized areas to get the Syrians to attack. The Syrians responded by firing at the tractors and shelling Israeli settlements.[125][126] Jan Mühren, a former UN observer in the area at the time, told a Dutch current affairs programme that Israel "provoked most border incidents as part of its strategy to annex more land".[127] UN officials blamed both Israel and Syria for destabilizing the borders.[128]

Six-Day War and Israeli occupation

After the Six-Day War broke out in June 1967, Syria's shelling greatly intensified[neutrality is disputed] and the Israeli army captured the Golan Heights on 9–10 June. The area that came under Israeli control as a result of the war consists of two geologically distinct areas: the Golan Heights proper, with a surface of 1,070 km2 (410 sq mi), and the slopes of the Mt. Hermon range, with a surface of 100 km2 (39 sq mi). The new ceasefire line was named the Purple Line. In the battle, 115 Israelis were killed and 306 wounded. An estimated 2,500 Syrians were killed, with another 5,000 wounded.[129]

During the war, between 80,000[130] and 131,000[131] Syrians fled or were driven from the Heights and around 7,000 remained in the Israeli-occupied territory.[131] Israeli sources and the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants reported that much of the local population of 100,000 fled as a result of the war, whereas the Syrian government stated that a large proportion of it was expelled.[132] Among those forced out was the Fadl tribe.[133] Israel has not allowed former residents to return, citing security reasons.[134] The remaining villages were Majdal Shams, Shayta (later destroyed), Ein Qiniyye, Mas'ade, Buq'ata and, outside the Golan proper, Ghajar.

Israeli settlement in the Golan began soon after the war. Merom Golan was founded in July 1967 and by 1970 there were 12 settlements.[135] Construction of Israeli settlements began in the remainder of the territory held by Israel, which was under military administration until Israel passed the Golan Heights Law extending Israeli law and administration throughout the territory in 1981.[18] On 19 June 1967, the Israeli cabinet voted to return the Golan to Syria in exchange for a peace agreement, although this was rejected after the Khartoum Resolution of 1 September 1967.[136][137] In the 1970s, as part of the Allon Plan, Israeli politician Yigal Allon proposed that a Druze state be established in Syria's Quneitra Governorate, including the Israeli-held Golan Heights. Allon died in 1980 and his plan never materialised.[138]

Yom Kippur War

During the Yom Kippur War in 1973, Syrian forces overran much of the southern Golan, before being pushed back by an Israeli counterattack. Israel and Syria signed a ceasefire agreement in 1974 that left almost all the Heights in Israeli hands. The 1974 ceasefire agreement between Israel and Syria delineated a demilitarized zone along their frontier and limited the number of forces each side can deploy within 25 kilometers (15 miles) of the zone.[139]

East of the 1974 ceasefire line lies the Syrian controlled part of the Heights, an area that was not captured by Israel (500 square kilometres or 190 sq mi) or withdrawn from (100 square kilometres or 39 sq mi). This area forms 30% of the Golan Heights.[140] Today,[when?] it contains more than 40 Syrian towns and villages. In 1975, following the 1974 ceasefire agreement, Israel returned a narrow demilitarised zone to Syrian control. Some of the displaced residents began returning to their homes located in this strip and the Syrian government began helping people rebuild their villages, except for Quneitra. In the mid-1980s the Syrian government launched a plan called "The Project for the Reconstruction of the Liberated Villages".[citation needed] By the end of 2007, the population of the Quneitra Governorate was estimated at 79,000.[141]

In the aftermath of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, in which Syria tried but failed to recapture the Golan, Israel agreed to return about 5% of the territory to Syrian civilian control. This part was incorporated into a demilitarised zone that runs along the ceasefire line and extends eastward. This strip is under the military control of UNDOF.[citation needed]

Mines deployed by the Syrian army remain active. As of 2003[update], there had been at least 216 landmine casualties in the Syrian-controlled Golan since 1973, of which 108 were fatalities.[142]

De facto annexation by Israel and civil rule

On 14 December 1981, Israel passed the Golan Heights Law,[18] that extended Israeli "laws, jurisdiction and administration" to the Golan Heights. Although the law effectively annexed the territory to Israel, it did not explicitly spell out a formal annexation.[143] The Golan Heights Law was declared "null and void and without international legal effect" by United Nations Security Council Resolution 497, which also demanded that Israel rescind its decision.[144][145][2][19]

During the negotiations regarding the text of United Nations Security Council Resolution 242, U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk explained that U.S. support for secure permanent frontiers did not mean the United States supported territorial changes.[146] The UN representative for the United Kingdom who was responsible for negotiating and drafting the Security Council resolution said that the actions of the Israeli Government in establishing settlements and colonizing the Golan are in clear defiance of Resolution 242.[147]

Syria continued to demand a full Israeli withdrawal to the 1967 borders, including a strip of land on the east shore of the Sea of Galilee that Syria captured during the 1948–49 Arab–Israeli War and occupied from 1949 to 1967. Successive Israeli governments have considered an Israeli withdrawal from the Golan in return for normalization of relations with Syria, provided certain security concerns are met. Prior to 2000, Syrian president Hafez al-Assad rejected normalization with Israel.

Since the passing of the Golan Heights Law, Israel has treated the Israeli-occupied portion of the Golan Heights as a subdistrict of its Northern District.[148] The largest locality in the region is the Druze village of Majdal Shams, which is at the foot of Mount Hermon, while Katzrin is the largest Israeli settlement. The region has 1,176 square kilometers.[148] The subdistrict has a population density of 36 inhabitants per square kilometer,[citation needed] and its population includes Arab, Jewish and Druze citizens. The district has 36 localities, of which 32 are Jewish settlements and four are Druze villages.[149][150]

The plan for the creation of the settlements, which had initially begun in October 1967 with a request for a regional agricultural settlement plan for the Golan, was formally approved in 1971 and later revised in 1976. The plan called for the creation of 34 settlements by 1995, one of which would be an urban center, Katzrin, and the rest rural settlements, with a population of 54,000, among them 40,000 urban and the remaining rural. By 1992, 32 settlements had been created, among them one city and two regional centers. The population total had however fallen short of Israel's goals, with only 12,000 Jewish inhabitants in the Golan settlements in 1992.[151]

Municipal elections in Druze towns

In 2016, a group of Druze lawyers petitioned the Supreme Court of Israel to allow elections for local councils in the Golan Druze towns of Majdal Shams, Buq'ata, Mas'ade, and Ein Qiniyye, replacing the previous system in which their members were appointed by the national government.[152]

On 3 July 2017, the Interior Ministry announced those towns would be included in the 2018 Israeli municipal elections. The turnout was just over 1%[153] with Druze religious leaders telling community members to boycott the elections or face shunning.[154][155][156]

The UN Human Rights Council issued a Resolution on Human Rights in the Occupied Syrian Golan on 23 March 2018 that included the statement "Deploring the announcement by the Israeli occupying authorities in July 2017 that municipal elections would be held on 30 October 2018 in the four villages in the occupied Syrian Golan, which constitutes another violation to international humanitarian law and to relevant Security Council resolutions, in particular resolution 497 (1981)".[157]

Israeli–Syrian peace negotiations

During United States-brokered negotiations in 1999–2000, Israel and Syria discussed a peace deal that would include Israeli withdrawal in return for a comprehensive peace structure, recognition and full normalization of relations. The disagreement in the final stages of the talks was on access to the Sea of Galilee. Israel offered to withdraw to the pre-1948 border (the 1923 Paulet-Newcombe line), while Syria insisted on the 1967 frontier. The former line has never been recognised by Syria, claiming it was imposed by the colonial powers, while the latter was rejected by Israel as the result of Syrian aggression.[158]

The difference between the lines is less than 100 meters for the most part, but the 1967 line would give Syria access to the Sea of Galilee, and Israel wished to retain control of the Sea of Galilee, its only freshwater lake and a major water resource.[158] Dennis Ross, U.S. President Bill Clinton's chief Middle East negotiator, blamed "cold feet" on the part of Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak for the breakdown.[159] Clinton also laid blame on Israel, as he said after the fact in his autobiography My Life.[160]

In June 2007, it was reported that Prime Minister Ehud Olmert had sent a secret message to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad saying that Israel would concede the land in exchange for a comprehensive peace agreement and the severing of Syria's ties with Iran and militant groups in the region.[161] On the same day, former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced that the former Syrian President, Hafez Assad, had promised to let Israel retain Mount Hermon in any future agreement.[162]

In April 2008, Syrian media reported Turkey's Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had told President Bashar al-Assad that Israel would withdraw from the Golan Heights in return for peace.[163][164] Israeli leaders of communities in the Golan Heights held a special meeting and stated: "all construction and development projects in the Golan are going ahead as planned, propelled by the certainty that any attempt to harm Israeli sovereignty in the Golan will cause severe damage to state security and thus is doomed to fail".[165] A 2008 survey found that 70% of Israelis oppose relinquishing the Golan for peace with Syria.[166]

In 2008, a plenary session of the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution 161–1 in favour of a motion on the Golan Heights that reaffirmed UN Security Council Resolution 497 and called on Israel to desist from "changing the physical character, demographic composition, institutional structure and legal status of the occupied Syrian Golan and, in particular, to desist from the establishment of settlements [and] from imposing Israeli citizenship and Israeli identity cards on the Syrian citizens in the occupied Syrian Golan and from its repressive measures against the population of the occupied Syrian Golan." Israel was the only nation to vote against the resolution.[167] Indirect talks broke down after the Gaza War began. Syria broke off the talks to protest Israeli military operations. Israel subsequently appealed to Turkey to resume mediation.[168]

In May 2009, Prime Minister Netanyahu said that returning the Golan Heights would turn it into "Iran's front lines which will threaten the whole state of Israel".[169][170] He said: "I remember the Golan Heights without Katzrin, and suddenly we see a thriving city in the Land of Israel, which having been a gem of the Second Temple era has been revived anew."[171] American diplomat Martin Indyk said that the 1999–2000 round of negotiations began during Netanyahu's first term (1996–1999), and he was not as hardline as he made out.[172]

In March 2009, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad claimed that indirect talks had failed after Israel did not commit to full withdrawal from the Golan Heights. In August 2009, he said that the return of the entire Golan Heights was "non-negotiable", it would remain "fully Arab", and would be returned to Syria.[173]

In June 2009, Israeli President Shimon Peres said that Assad would have to negotiate without preconditions, and that Syria would not win territorial concessions from Israel on a "silver platter" while it maintained ties with Iran and Hezbollah.[174] In response, Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Muallem demanded that Israel unconditionally cede the Golan Heights "on a silver platter" without any preconditions, adding that "it is our land," and blamed Israel for failing to commit to peace. Syrian President Assad claimed that there was "no real partner in Israel".[175]

In 2010, Israeli foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman said: "We must make Syria recognise that just as it relinquished its dream of a greater Syria that controls Lebanon ... it will have to relinquish its ultimate demand regarding the Golan Heights."[176]

Syrian Civil War

From 2012 to 2018 in the Syrian Civil War, the eastern Golan Heights became a scene of repeated battles between the Syrian Arab Army, rebel factions of the Syrian opposition including the moderate Southern Front and jihadist al-Nusra Front, and factions affiliated with the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) terrorist group.

The atrocities of the Syrian Civil War and the rise of ISIL, which from 2016 to 2018 controlled parts of the Syrian-administered Golan, have added a new twist to the issue. In 2015, it was reported that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu asked US President Barack Obama to recognize Israeli claims to the territory because of these recent ISIL actions and because he said that modern Syria had likely "disintegrated" beyond the point of reunification.[177] The White House dismissed Netanyahu's suggestion, stating that President Obama continued to support UN resolutions 242 and 497, and any alterations of this policy could strain American alliances with Western-backed Syrian rebel groups.[178]

In 2016, the Islamic State apologized to Israel after a fire exchange with Israeli soldiers in the area.[179] In May 2018, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) launched "extensive" air strikes against alleged Iranian military installations in Syria after 20 Iranian rockets were reportedly launched at Israeli army positions in the Western Golan Heights.[180]

On 17 April 2018 in the aftermath of the 2018 missile strikes against Syria by the United States, France, and the United Kingdom about 500 Druze in the Golan town of Ein Qiniyye marched in support of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad on Syria's Independence day and in condemnation of the American-led strikes.[181][182]

On 31 July 2018, after waging a month-long military offensive against the rebels and ISIL, the Syrian government regained control of the eastern Golan Heights.[21]

2023–2024 war

In June 2024, Hezbollah launched a series of retaliatory rocket and drone attacks in the Golan Heights, resulting in the destruction of 10,000 dunams of open areas by fire. It was in response to Israel's attack on Hezbollah targets in Lebanon. The fire damaged parts of the Yehudiya Forest Nature Reserve, including hiking trails and the reserve's Black Canyon. According to an official from the Nature and Parks Authority, it will take years for the local flora to recover.[183]

On 27 July 2024, a rocket from Southern Lebanon struck a soccer field in the Druze town of Majdal Shams in the Golan Heights.[184] The strike resulted in the deaths of 12 Druze children. The IDF stated the rocket was fired by Hezbollah, a claim which Hezbollah denied.[185]

Following the 2024 Syrian opposition offensives and the fall of the Assad regime, Prime Minister Netanyahu ordered Israeli forces to seize the buffer zone on 8 December 2024, citing the abandonment of Syrian positions and the collapse of the 1974 ceasefire agreement.[186] Israeli forces also launched strikes on Syrian military assets, including air stirkes destroying the Syrian Navy and, it was claimed, 90% of Syria’s known surface-to-air missiles.[187]

Israel started violating the 1974 Disengagement Agreement before Assad's fall in November with engineering work and battle tanks inside the demilitarized zone.[188] UNDOF had: "repeatedly engaged with the IDF to protest the construction"[188] In December, Israeli forces occupied Mount Hermon advancing as far as the town of Beqaasem, situated about 25 kilometers from Damascus. Holding Mount Hermon - at 2,800 meters the highest point in Syria - would faciliate Israeli electronic surveillance deep in Syrian territory and provide additional warning with respect to military developments in the region.[189]

Territorial claims

Claims on the territory include the fact that an area in northwestern of the Golan region, delineated by a rough triangle formed by the towns of Banias, Quneitra and the northern tip of the Sea of Galilee, was temporarily part of the British Palestine Mandate in which the establishment of a Jewish national home had been promised.[190] In 1923, this triangle in northwestern Golan was ceded to the French Mandate in Syria, but in exchange for this, land areas in Syria and Lebanon was ceded to Palestine, and the whole of the Sea of Galilee which previously had its eastern boundary connected to Syria was placed inside Palestine.[191]

Syrian counters that the region was placed in the Vilayet of Damascus as part of Syria under the Ottoman boundaries, and that the 1920 Franco-British agreement, which had placed part of the Golan under the control of Britain, was only temporary. Syria further holds that the final border line drawn up in 1923, which excluded the Golan triangle, had superseded the 1920 agreement,[190] although Syria has never recognised the 1923 border as legally binding.

Israel considers the Golan Heights vital for its national security, asserting that control over the region is necessary to defend against threats from Syria and Iranian proxy groups.[192] It maintains that it may retain the area, as the text of Resolution 242 calls for "safe and recognised boundaries free from threats or acts of force".[193]

Borders, armistice line and ceasefire line

One of the aspects of the dispute involves the existence prior to 1967 of three different lines separating Syria from the area that before 1948 was referred to as Mandatory Palestine.

The 1923 boundary between British Mandatory Palestine and the French Mandate of Syria was drawn with water in mind.[194][better source needed] Accordingly, it was demarcated so that all of the Sea of Galilee, including a 10-metre (33 ft) wide strip of beach along its northeastern shore, would stay inside Mandatory Palestine. From the Sea of Galilee north to Lake Hula the boundary was drawn between 50 and 400 metres (160 and 1,310 ft) east of the upper Jordan River, keeping that stream entirely within Mandatory Palestine. The British also received a sliver of land along the Yarmouk River, out to the present-day Hamat Gader.[195]

During the Arab–Israeli War, Syria captured various areas of the formerly British controlled Mandatory Palestine, including the 10-meter strip of beach, the east bank of the upper Jordan, as well as areas along the Yarmouk.

While negotiating the 1949 Armistice Agreements, Israel called for the removal of all Syrian forces from the former Palestine territory. Syria refused, insisting on an armistice line based not on the 1923 international border but on the military status quo. The result was a compromise. Under the terms of an armistice signed on 20 July 1949, Syrian forces were to withdraw east of the old Palestine-Syria boundary. Israeli forces were to refrain from entering the evacuated areas, which would become a demilitarised zone, "from which the armed forces of both Parties shall be totally excluded, and in which no activities by military or paramilitary forces shall be permitted."[196][better source needed]

Accordingly, major parts of the armistice lines departed from the 1923 boundary. There were three distinct, non-contiguous enclaves—to the west of Banias, on the west bank of the Jordan River near Lake Hula, and the eastern-southeastern shores of the Sea of Galilee extending out to Hamat Gader, consisting of 66.5 km2 (25.7 sq mi) of land lying between the 1949 armistice line and the 1923 boundary, forming the demilitarised zone.[194][better source needed]

Following the armistice, both Israel and Syria sought to take advantage of the territorial ambiguities left in place by the 1949 agreement. This resulted in an evolving tactical situation, one "snapshot" of which was the disposition of forces immediately prior to the Six-Day War, the "line of June 4, 1967".[194][better source needed]

Shebaa Farms

A small portion of territory in the Golan Heights, on the Lebanon–Syria border, has been a particular flashpoint. The territory, known as the Shebaa Farms, measures only 22 km2 (8.5 sq mi). Since 2000, Lebanon has officially claimed it to be Lebanese territory from which Israel should withdraw, and Syria has concurred.[197][198][199]

The approximate boundary between Lebanon and Syria has its origins in an 1862 French map.[200][201] During the early period of the French Mandate, both French and British maps were inconsistent regarding the boundary in the western Golan region, with some showing the Shebaa Farms in Lebanon and others, the majority, showing them in Syria.[202] However, by 1936 the disagreement was eliminated by high quality maps showing the Shebaa Farms in Syria, and these formed the basis of later official maps.[203] According to Kaufman, the choice between the two options was due to a preference for drawing boundaries along watersheds rather than along valleys.[203] However, no detailed delineation or demarcation was performed throughout the mandate period.

Meanwhile, problems were reported with the location of the boundary.[204] Several official documents from the 1930s state that the boundary lies along the Wadi al-'Asal (to the south of the Shebaa Farms).[204] Local officials of the French administration reported that the de facto boundary did not correspond to the boundary shown on maps.[204] The High Commissioner requested a Syrian–Lebanese negotiation but apparently nothing happened.[204]

From the founding of the Syrian Republic in 1946 until the Israeli occupation in 1967, the Shebaa Farms were controlled by Syria and Lebanon did not make any known official complaint.[205][206] The Israel occupation cut off the access of many Lebanese residents from the farms they had worked.[206] In the context of renewal of the UNIFIL mandate, the Lebanese government implicitly endorsed United Nations maps of the region in 1978 and many times later, even though the maps showed the Shebaa Farms in Syria.[205]

Lebanese newspapers, residents and politicians lobbied the Lebanese government in the early 1980s to take up the issue, but it was apparently not raised in the failed negotiations for an Israeli withdrawal after the 1982 Israeli invasion.[207] A series of publications appeared, partly assisted by Hezbollah and Amal, and a committee which formed in the Lebanese town of Shebaa wrote to the UN in 1986 protesting Israeli occupation of their lands.[207] However, it was Hezbollah in 2000 which first adopted the Shebaa Farms as the basis for a public territorial claim against Israel.[208]

On 7 June 2000, the United Nations published the Blue Line as the line to which Israel should withdraw from Lebanon in accordance with Security Council Resolution 425. The UN chose to follow the maps at its disposal and did not accept the Lebanese complaint from several weeks earlier that the Shebaa Farms were in Lebanon.[209][210] After the Israeli withdrawal, the United Nations affirmed on 18 June 2000 that Israel had withdrawn its forces from Lebanon.[211] However, the press release noted that both Lebanon and Syria disagreed, considering the Shebaa Farms area to be Lebanese.[211] In deference to the Lebanese position, the Blue Line is not marked on the ground in this location.[212]

The attitude of the UN shifted during the following years. In 2006, the Lebanese government presented the UN with a seven-point plan that included a proposal to place the Shebaa Farms under UN administration until boundary demarcation and sovereignty were settled.[213] In August of that year, the Security Council passed Resolution 1701 which "took due note" of the Lebanese plan and called for "delineation of the international borders of Lebanon, especially in those areas where the border is disputed or uncertain, including by dealing with the Shebaa farms area".[213][214]

In 2007, a UN cartographer delineated the boundaries of the region: "starting from the turning point of the 1920 French line located just south of the village of El Majidiye; from there continuing south-east along the 1946 Moughr Shab'a-Shab'a boundary until reaching the thalweg of the Wadi al-Aasal; thence following the thalweg of the wadi north-east until reaching the crest of the mountain north of the former hamlet Mazraat Barakhta and reconnecting with the 1920 line."[215] As of 2023, neither Syria nor Israel have responded to the delineation, nor have Lebanon and Syria made progress towards border demarcation.[216]

The position of Israel, which occupied the Golan Heights in 1967 and annexed them in 1981 to the disapproval of the international community, is that the Shebaa Farms belonged to Syria and there is no case for Lebanese sovereignty.[217][212]

Ghajar

The village of Ghajar is another complex border issue west of Shebaa farms. Before the 1967 war this Alawite village was in Syria. Residents of Ghajar accepted Israeli citizenship in 1981.[218] It is divided by an international boundary, with the northern part of the village on the Lebanese side since 2000. Most residents hold dual Syrian and Israeli citizenship.[219] Residents of both parts hold Israeli citizenship, and in the northern part often a Lebanese passport as well. Today the entire village is surrounded by a fence, with no division between the Israeli-occupied and Lebanese sides. There is an Israeli army checkpoint at the entrance to the village from the rest of the Golan Heights.[206]

International views

The international community largely considers the Golan to be Syrian territory held under Israeli occupation.[220][221][222][223][1][224]

On 25 March 2019, then-President of the United States Donald Trump proclaimed U.S. recognition of the Golan Heights as a part of the State of Israel, making it the first country to do so.[225][226] Israeli officials lobbied the United States into recognizing "Israeli sovereignty" over the territory.[227] The 28 member states of the European Union declared in turn that they do not recognize Israeli sovereignty, and several experts on international law reiterated that the principle remains that land gained by either defensive or offensive wars cannot be legally annexed under international law.[228][229][230] The European members of the UN Security Council issued a joint statement condemning the U.S. announcement and the UN Secretary-General issued a statement saying that the status of the Golan had not changed.[231]

Under the subsequent administration of President Joe Biden, the U.S. State Department's annual report on human rights violations around the world once more refers to the West Bank, Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights as being territories occupied by Israel.[232] In June 2021, the Biden administration affirmed that it will continue to maintain the previous administration's policy of recognizing Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights.[233]

UNDOF supervision

UNDOF, the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force, was established in 1974 to supervise the implementation of the Agreement on Disengagement and maintain the ceasefire with an area of separation known as the UNDOF Zone. Currently there are more than 1,000 UN peacekeepers there trying to sustain a peace.[234] Syria and Israel still contest the ownership of the Heights but have not used overt military force since 1974.

The great strategic value of the Heights both militarily and as a source of water means that a deal is uncertain. Members of the UN Disengagement force are usually the only individuals who cross the Israeli–Syrian de facto border (cease fire "Alpha Line"), but since 1988 Israel has allowed Druze pilgrims to cross into Syria to visit the shrine of Abel on Mount Qasioun. Since 1967, Druze brides have been allowed to cross into Syria, although they do so in the knowledge that they may not be able to return.

Though the cease fire in the UNDOF zone has been largely uninterrupted since the seventies, in 2012 there were repeated violations from the Syrian side, including tanks[235] and live gunfire,[236] though these incidents are attributed to the ongoing Syrian Civil War rather than intentionally directed towards Israel.[237] On 15 October 2018 the Quneitra border crossing between the Golan Heights and Syria reopened for United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) personnel after four years of closure.[238]

Syrian villages

The population of the Golan Heights prior to the 1967 Six-Day War has been estimated between 130,000 and 145,000, including 17,000 Palestinian refugees registered with UNRWA.[239] Between 80,000[130] and 130,000[131] Syrians fled or were driven from the Heights during the Six-Day War and around 7,000 remained in the Israeli-held territory in six villages: Majdal Shams, Mas'ade, Buq'ata, Ein Qiniyye, Ghajar and Shayta.[131]

Before the 1967 war, Christians comprised 12% of the total population of the Golan Heights. The vast majority of Christians migrated with the rest of the population after Israel's occupation of the Golan, leaving only a few small Christian families in Majdal Shams and Ein Qiniyye.[240][241]

Israel forcibly expelled Syrians from the Golan Heights.[242][243] There were also instances of Israeli soldiers killing Syrian residents including blowing up their home with people inside.[244]

Israel demolished over one hundred Syrian villages and farms in the Golan Heights.[245][246] After the demolitions, the lands were given to Israeli settlers.[247]

Quneitra was the largest town in the Golan Heights until 1967, with a population of 27,000. It was occupied by Israel on the last day of the Six-Day War and handed back to Syrian civil control per the 1974 Disengagement Agreement. But the Israelis had destroyed Quneitra with dynamite and bulldozers before they withdrew from the city.[248][249]

East of the 1973 ceasefire line, in the Syrian controlled part of the Golan Heights, an area of 600 km2 (232 sq mi), are more than 40 Syrian towns and villages, including Quneitra, Khan Arnabah, al-Hamidiyah, al-Rafid, al-Samdaniyah, al-Mudariyah, Beer Ajam, Bariqa, Ghadir al-Bustan, Hader, Juba, Kodana, Ufaniyah, Ruwayhinah, Nabe' al-Sakhar, Trinjah, Umm al-A'zam, and Umm Batna. The population of the Quneitra Governorate numbers 79,000.[141]

Once annexing the Golan Heights in 1981, the Israeli government offered all non-Israelis living in the Golan citizenship, but until the early 21st century fewer than 10% of the Druze were Israeli citizens; the remainder held Syrian citizenship.[250] The Golan Alawites in the village of Ghajar accepted Israeli citizenship in 1981.[218] In 2012, due to the situation in Syria, young Druze have applied to Israeli citizenship in much larger numbers than in previous years.[251]

In 2012, there were 20,000 Druze with Syrian citizenship living in the Israeli-occupied portion Golan Heights.[252]

The Druze living in the Golan Heights are permanent residents of Israel. They hold laissez-passer documents issued by the Israeli government, and enjoy the country's social-welfare benefits.[253] The pro-Israeli Druze were historically ostracized by the pro-Syrian Druze.[254] Reluctance to accept citizenship also reflects fear of ill treatment or displacement by Syrian authorities should the Golan Heights eventually be returned to Syria.[255]

According to The Independent, most Druze in the Golan Heights live relatively comfortable lives in a freer society than they would have in Syria under Assad's government.[256] According to Egypt's Daily Star, their standard of living vastly surpasses that of their counterparts on the Syrian side of the border. Hence their fear of a return to Syria, though most of them identify themselves as Syrian,[257] but feel alienated from the "autocratic" government in Damascus. According to the Associated Press, "many young Druse have been quietly relieved at the failure of previous Syrian–Israeli peace talks to go forward."[220]

On the other hand, expressing pro-Syrian viewpoint, The Economist represents the Golan Druzes' view that by doing so they may be potentially rewarded by Syria, while simultaneously risking nothing in Israel's freewheeling society. The Economist likewise reported that "Some optimists see the future Golan as a sort of Hong Kong, continuing to enjoy the perks of Israel's dynamic economy and open society, while coming back under the sovereignty of a stricter, less developed Syria." The Druze are also reportedly well-educated and relatively prosperous, and have made use of Israel's universities.[258]

Since 1988, Druze clerics have been permitted to make annual religious pilgrimages to Syria. Since 2005, Israel has allowed Druze farmers to export some 11,000 tons of apples to the rest of Syria each year, constituting the first commercial relations between Syria and Israel.[220]

In the first years after the breakout of the Syrian Civil War in 2012, the number of applications for Israeli citizenship grew, although Syrian loyalty remained strong and those who applied for citizenship were often ostracized by members of the older generation.[259] In recent years, the number of applications for citizenship has increased, 239 in 2021 and 206 in the first half of 2022. In 2022, official Israeli figures suggest that of approximately 21,000 Druze living in the Golan Heights, about 4,300 (or around 20 percent) were Israeli citizens.[260]

-

A demographic map of Quneitra Governorate (Golan Heights) before the 1967 six day war

-

A demographic map of Quneitra Governorate (Golan Heights) today. Excludes any permanent depopulation or repopulation that might have happened during the Syrian civil war

-

A demographic map of Quneitra Governorate (Golan Heights) overlaid with the location of the depopulated Syrian localities

Israeli settlements

Israeli settlement activity began in the 1970s. The area was governed by military administration until 1981 when Israel passed the Golan Heights Law, which extended Israeli law and administration throughout the territory.[18] This move was condemned by the United Nations Security Council in UN Resolution 497,[2][19] although Israel states it has a right to retain the area, citing the text of UN Resolution 242, adopted after the Six-Day War, which calls for "safe and recognised boundaries free from threats or acts of force".[193] The continued Israeli control of the Golan Heights remains controversial and is still regarded as an occupation by most countries other than Israel and the United States. Israeli settlements and human rights policy in the occupied territory have drawn criticism from the UN.[261][262]

The Israeli-occupied territory is administered by the Golan Regional Council, based in Katzrin, which has a population of 7,600. There are another 19 moshavim and 10 kibbutzim. In 1989, the Israeli settler population was 10,000.[263] By 2010 the Israeli settler population had expanded to 20,000[264] living in 32 settlements.[265][266] By 2019 it had expanded to 22,000.[267] In 2021, the Israeli settler population was estimated to be 25,000 with plans by the Government of Prime Minister Naftali Bennett to double that population over a five-year period.[268]

On 23 April 2019, Israel Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced that he would bring a resolution for government approval to name a new community in the Golan Heights after U.S. President Donald Trump.[269] The planned settlement was unveiled as Trump Heights on 16 June 2019.[270][271] Further plans for settlement expansion on the Golan were part of the agenda of Benjamin Netanyahu's incoming coalition in 2023.[272]

In December 2024, Prime Minister Netanyahu announced an updated plan to further expand settlements on the Golan Heights.[273] As of the end of 2024, the Israeli settler population was estimated to be about 31,000 people.[274]

Geography

Geology

The plateau that Israel controls is part of a larger area of volcanic basalt fields stretching north and east that were created in the series of volcanic eruptions that began recently in geological terms, almost 4 million years ago.[275] The rock forming the mountainous area in the northern Golan Heights, descending from Mount Hermon, differs geologically from the volcanic rocks of the plateau and has a different physiography. The mountains are characterised by lighter-colored, Jurassic-age limestone of sedimentary origin. Locally, the limestone is broken by faults and solution channels to form a karst-like topography in which springs are common.

Geologically, the Golan plateau and the Hauran plain to the east constitute a Holocene volcanic field that also extends northeast almost to Damascus. Much of the area is scattered with dormant volcanos, as well as cinder cones, such as Majdal Shams. The plateau also contains a crater lake, called Birkat Ram ("Ram Pool"), which is fed by both surface runoff and underground springs. These volcanic areas are characterised by basalt bedrock and dark soils derived from its weathering. The basalt flows overlie older, distinctly lighter-colored limestones and marls, exposed along the Yarmouk River in the south.

Boundaries

The geographic definition of the Golan varies but is generally defined as the area bound by the Jordan Valley to the west, which separates it from the Galilee in Israel, the Yarmouk River to the south, which separates it from the Jabal Ajlun region in Jordan, and the Sa'ar stream (a tributary of Nahal Hermon/Nahr Baniyas) to the north which separates it from Mount Hermon and the Hula Valley close to the border with Lebanon. The natural eastern boundary of the region is alternatively placed at the Ruqqad river or the Allan river further east, which separate the Golan from the Hauran plain of Syria.[276]

Size

The plateau's north–south length is approximately 65 km (40 mi) and its east–west width varies from 12 to 25 km (7.5 to 15.5 mi).[277][278]

Israel has captured, according to its own data, 1,150 km2 (440 sq mi).[279] According to Syria, the Golan Heights measures 1,860 km2 (718 sq mi), of which 1,500 km2 (580 sq mi) are occupied by Israel.[280] According to the CIA, Israel holds 1,300 km2 (500 sq mi).[281]

Topography

The area is hilly and elevated, overlooking the Jordan Rift Valley which contains the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan River, and is itself dominated by the 2,814 m (9,232 ft) tall Mount Hermon.[282][281] The Sea of Galilee at the southwest corner of the plateau[277] and the Yarmouk River to the south are at elevations well below sea level[281] (the sea of Galilee at about 200 m (660 ft)).[277]

Topographically, the Golan Heights is a plateau with an average altitude of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft),[281] rising northwards toward Mount Hermon and sloping down to about 400 m (1,300 ft) elevation along the Yarmouk River in the south.[277] The steeper, more rugged topography is generally limited to the northern half, including the foothills of Mount Hermon; on the south the plateau is more level.[277]

There are several small peaks on the Golan Heights, most of them volcanic cones, such as Mount Agas (1,350 m, 4,430 ft), Mount Dov/Jebel Rous (1,529 m, 5,016 ft; northern peak 1,524 m, 5,000 ft),[283] Mount Bental (1,171 m, 3,842 ft) and opposite it Mount Avital (1,204 m, 3,950 ft), Mount Ram (1,188 m, 3,898 ft), and Tal Saki (594 metres, 1,949 ft).

Subdivisions

The broader Golan plateau exhibits a more subdued topography, generally ranging between 120 and 520 m (390 and 1,710 ft) in elevation. In Israel, the Golan plateau is divided into three regions: northern (between the Sa'ar and Jilabun valleys), central (between the Jilabun and Daliyot valleys), and southern (between the Daliyot and Yarmouk valleys). The Golan Heights is bordered on the west by a rock escarpment that drops 500 m (1,600 ft) to the Jordan River valley and the Sea of Galilee. In the south, the incised Yarmouk River valley marks the limits of the plateau and, east of the abandoned railroad bridge upstream of Hamat Gader and Al Hammah, it marks the recognised international border between Syria and Jordan.[284]

Climate and hydrology

In addition to its strategic military importance, the Golan Heights is an important water resource, especially at the higher elevations, which are snow-covered in the winter and help sustain baseflow for rivers and springs during the dry season. The Heights receive significantly more precipitation than the surrounding, lower-elevation areas. The occupied sector of the Golan Heights provides or controls a substantial portion of the water in the Jordan River watershed, which in turn provides a portion of Israel's water supply. The Golan Heights supplies 15% of Israel's water.[285]

Landmarks

The Golan Heights features numerous archeological sites, mountains, streams and waterfalls. Throughout the region 25 ancient synagogues have been found dating back to the Roman and Byzantine periods.[286][287]

- Banias (Arabic: بانياس الحولة; Hebrew: בניאס) is an ancient site that developed around a spring once associated with the Greek god Pan. Near the archaeological site is the Banias Waterfall, one of the most powerful waterfalls in the region, plunging about 10 meters into a pool surrounded by lush vegetation. Part of the stream is accessible via a 100-meter-long suspended walkway.[288]

- Deir Qeruh (Arabic: دير قروح; Hebrew: דיר קרוח) is a ruined Byzantine-period and Syrian village. Founded in the 4th century AD, it has a monastery and church of St George from the 6th century. The church has a square apse – a feature known from ancient Syria and Jordan, but not present in churches west of the Jordan River.[289]

- Kursi (Arabic: الكرسي; Hebrew: כורסי) is an archaeological site and national park on the shore of the Sea of Galilee at the foothills of the Golan, containing the ruins of a Byzantine Christian monastery connected to the Gospels (Gergesa).

- Katzrin (Arabic: قصرين; Hebrew: קצרין) is the administrative and commercial center of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. Katzrin Ancient Village is an archaeological site on the outskirts of Katzrin where the remains of a Talmud-era village and synagogue have been reconstructed.[290] The site has been described by an archeologist as being developed: "with a clear agenda and nationalistic narrative."[291] It has also been criticized for distorting historical items and showing a selective part of history, focusing on the Jewish period leaving out the Mamluk and Syrian periods.[292][293] Golan Archaeological Museum hosts archaeological finds uncovered in the Golan Heights from prehistoric times. A special focus concerns Gamla and excavations of synagogues and Byzantine churches.[294]

- Gamla Nature Reserve (Hebrew: שמורת טבע גמלא) is an open park with the archaeological remains of the ancient Jewish city of Gamla (Hebrew: גמלא, Arabic: جمالا) — including a tower, wall and synagogue. It is also the site of a large waterfall, an ancient Byzantine church, and a panoramic spot to observe the nearly 100 vultures that dwell in the cliffs. Israeli scientists study the vultures and tourists can watch them fly and nest.[295]

- A ski resort on the slopes of Mount Hermon (Arabic: جبل الشيخ; הר חרמון) features a wide range of ski trails and activities. Several restaurants are located in the area. The Lake Ram crater lake is nearby.

- Hippos (Arabic: قلعة الحصن; Hebrew: סוסיתא) is an ancient Greco-Roman city, known in Arabic as Qal'at al-Hisn and in Aramaic as Susita. The archaeological site includes excavations of the city's forum, the small imperial cult temple, a large Hellenistic temple compound, the Roman city gates, and two Byzantine churches.

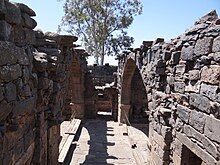

- The Nimrod Fortress (Arabic: لعة الصبيبة; Hebrew: מבצר נמרוד) was built against the Crusaders, served the Ayyubids and Mamluks, and was captured only once, in 1260, by the Mongols. It is now located inside a nature reserve.

- Rujm el-Hiri (Arabic: رجم الهري; Hebrew: גלגל רפאים) is a large circular stone monument. Excavations since 1968 have not uncovered material remains common to archaeological sites in the region. Archaeologists believe the site may have been a ritual center linked to a cult of the dead.[296] A 3D model of the site exists in the Museum of Golan Antiquities in Katzrin.

- Senaim (Arabic: جبل الحلاوة; Hebrew: הר סנאים) is an archaeological site in northern Golan Heights that includes both Roman and Ancient Greek temples. Byzantine and Mamluk coins have also been found at this site.

- Tell Hadar (Hebrew: תל הדר) is an Aramean archaeological site.

- Umm el-Qanatir (Arabic: ام القناطر; Hebrew: עין קשתות, Ein Keshatot) is another impressive set of standing ruins of a village of the Byzantine era. The site includes a very large synagogue and two arches next to a natural spring.[297]

Economy

Viticulture

On a visit to Israel and the Golan Heights in 1972, Cornelius Ough, a professor of viticulture and oenology at the University of California, Davis, pronounced conditions in the Golan very suitable for the cultivation of wine grapes.[298] A consortium of four kibbutzim and four moshavim took up the challenge, clearing 250 burnt-out tanks in the Golan's Valley of Tears to plant vineyards for what would eventually become the Golan Heights Winery.[299] The first vines were planted in 1976, and the first wine was released by the winery in 1983.[298] As of 2012[update], The Heights are home to about a dozen wineries.[300]

Oil and gas exploration

In the early 1990s, the Israel National Oil Company (INOC) was granted shaft-sinking permits in the Golan Heights. It estimated a recovery potential of two million barrels of oil, equivalent at the time to $24 million. During the Yitzhak Rabin administration (1992–1995), the permits were suspended as efforts were undertaken to restart peace negotiations between Israel and Syria. In 1996, Benjamin Netanyahu granted preliminary approval to INOC to proceed with oil exploration drilling in the Golan.[301][302][303]

INOC began undergoing a process of privatization in 1997, overseen by then-Director of the Government Companies Authority (GCA), Tzipi Livni. During that time, it was decided that INOC's drilling permits would be returned to the state.[304][305] In 2012, National Infrastructure Minister Uzi Landau approved exploratory drilling for oil and natural gas in the Golan.[306] The following year, the Petroleum Council of Israel's Ministry of Energy and Water Resources secretly awarded a drilling license covering half the area of the Golan Heights to a local subsidiary of New Jersey–based Genie Energy Ltd. headed by Effi Eitam.[307][308]

Human rights groups have said that the drilling violates international law, as the Golan Heights are an occupied territory.[309]

On 18 November 2021, the United Nations Second Committee approved a draft resolution that demanded that: "Israel, the occupying Power, cease the exploitation, damage, cause of loss or depletion and endangerment of the natural resources in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and in the occupied Syrian Golan".[310][311]

See also

- Al-Marsad

- Borders of Israel

- Israeli-occupied territories

- Front for the Liberation of the Golan

- Golan Heights wind farm

- Golan Regional Council

- Golan Regiment, a Syrian para-military force

- Independent Israel–Syria peace initiatives

- International law and the Arab–Israeli conflict

- Israel–Syria relations

- Petroleum Road

- Shouting Hill

- Syrian towns and villages depopulated in the Arab–Israeli conflict

- UN Security Council Resolution 242

- UN Security Council Resolution 452

- UN Security Council Resolution 465

- UN Security Council Resolution 471

Explanatory notes

- ^ see Status of the Golan Heights

- ^ The United States recognized Israeli sovereignty over the Golan in March 2019. The U.S. is the first country to recognize the Golan as Israeli territory, while the rest of the international community still considers it Syrian territory occupied by Israel.[3][4]

- ^ Arabic: هَضْبَةُ الْجَوْلَانِ, romanized: Haḍbatu l-Jawlān or مُرْتَفَعَاتُ الْجَوْلَانِ, Murtafaʻātu l-Jawlān; Hebrew: רמת הגולן, Ramat HaGolan, ⓘ

- ^ The resolution stated: "the Israeli decision to impose its laws, jurisdiction, and administration in the occupied Syrian Golan Heights is null and void and without international legal effect".[19]

References

- ^ a b c *"The international community maintains that the Israeli decision to impose its laws, jurisdiction and administration in the occupied Syrian Golan is null and void and without international legal effect." International Labour Office (2009). The situation of workers of the occupied Arab territories (International government publication ed.). International Labour Office. p. 23. ISBN 978-92-2-120630-9.

- In 2008, a plenary session of the United Nations General Assembly voted by 161–1 in favour of a motion on the "occupied Syrian Golan" that reaffirmed support for UN Resolution 497. (General Assembly adopts broad range of texts, 26 in all, on recommendation of its fourth Committee, including on decolonization, information, Palestine refugees Archived 27 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations, 5 December 2008.)

- "the Syrian Golan Heights territory, which Israel has occupied since 1967". Also, "the Golan Heights, a 450-square mile portion of southwestern Syria that Israel occupied during the 1967 Arab–Israeli war." (CRS Issue Brief for Congress: Syria: U.S. Relations and Bilateral Issues Archived 26 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Congressional Research Service. 19 January 2006)

- ^ a b c d e Korman, Sharon, The Right of Conquest: The Acquisition of Territory by Force in International Law and Practice, Oxford University Press, pp. 262–263