Steve Earle

Steve Earle | |

|---|---|

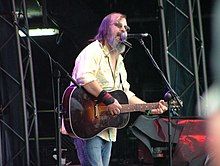

Earle performing at the Rudolstadt-Festival in 2018 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Stephen Fain Earle |

| Born | January 17, 1955 Fort Monroe, Virginia, U.S. |

| Origin | San Antonio, Texas, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments | |

| Years active | 1968–present[4] |

| Labels |

|

| Website | steveearle |

Stephen Fain Earle (/ɜːrl/; born January 17, 1955) is an American country, rock and folk singer-songwriter. He began his career as a songwriter in Nashville and released his first EP in 1982.

Earle's breakthrough album was the 1986 debut album Guitar Town; the eponymous lead single peaked at number 7 on the Billboard Hot Country chart. Since then, he has released 20 more studio albums and received three Grammy awards each for Best Contemporary Folk Album; he has four additional nominations in the same category. "Copperhead Road" was released in 1988 and is his bestselling single; it peaked on its initial release at number 10 on the Mainstream Rock chart, and had a 21st-century resurgence reaching number 15 on the Hot Rock & Alternative Songs chart, buoyed by vigorous online sales. His songs have been recorded by Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Levon Helm, The Highwaymen, Travis Tritt, Vince Gill, Patty Loveless, Shawn Colvin, Bob Seger, Percy Sledge, Dailey & Vincent, and Emmylou Harris.[5]

Earle has appeared in film and television, most notably as recurring characters in HBO's critically acclaimed shows The Wire and Treme. He has also written a novel, a play, and a book of short stories. Earle is the father of late singer-songwriter Justin Townes Earle with whom he frequently collaborated.

Early life

[edit]Earle was born on January 17, 1955[6] in Fort Monroe, Virginia, where his father was stationed as an air traffic controller.[7] The family moved to Texas before Earle's second birthday and he grew up primarily in the San Antonio area.[8][9][10][11]

Earle began learning the guitar at the age of 11 and entered a school talent contest at age 13.[8] He ran away from home at age 14 to search for his idol, singer-songwriter Townes Van Zandt.[12] Earle was "rebellious" as a young man and dropped out of school at the age of 16. He moved to Houston with his 19-year-old uncle, also a musician. While in Houston Earle finally met Van Zandt.[8][11] Earle was opposed to the Vietnam War as he recalled in 2012: "The anti-war movement was a very personal thing for me. I didn't finish high school, so I wasn't a candidate for a student deferment. I was fucking going."[13] The end of the Selective Service Act and the draft lottery in 1973 prevented him from being drafted, but several of his friends were drafted, which he credits as the origin of his politicization.[13] Earle also noted that when he was a young man, his girlfriend was able to get an abortion despite the fact that abortion was illegal. Her father was a doctor at the local hospital in San Antonio while several other girls he knew at the time were not able to get abortions; they lacked access to those with the necessary power to arrange an abortion, which he credits as the origin of his pro-choice views.[13]

Career

[edit]1974–1999

[edit]In 1974, at the age of 19,[7] Earle moved to Nashville and began working blue-collar jobs during the day and playing music at night.[8] During this period Earle wrote songs and played bass guitar in Guy Clark's band and sang on Clark's 1975 album Old No. 1.[11] Earle appeared in the 1976 film Heartworn Highways, a documentary on the Nashville music scene which included David Allan Coe, Guy Clark, Townes van Zandt, and Rodney Crowell. Earle lived in Nashville for several years and assumed the position of staff songwriter at the publishing company Sunbury Dunbar.[8][11] Later Earle grew tired of Nashville and returned to Texas where he started a band called The Dukes.[11]

In the 1980s, Earle returned to Nashville once again and worked as a songwriter for the publishers Roy Dea and Pat Carter. A song he co-wrote, "When You Fall in Love", was recorded by Johnny Lee and made number 14 on the country charts in 1982.[8] Carl Perkins recorded Earle's song "Mustang Wine", and two of his songs were recorded by Zella Lehr. Later Dea and Carter created an independent record label called LSI and invited Earle to begin recording his own material on their label.[11] Connie Smith recorded Earle's composition "A Far Cry from You" in 1985 which reached a minor position on the country charts as well.[14]

Earle released an EP called Pink & Black in 1982 featuring the Dukes. Acting as Earle's manager, John Lomax sent the EP to Epic Records, and they signed Earle to a recording contract in 1983.[11] In 1983, Earle signed a record deal with CBS and recorded a "neo-rockabilly album".[12]

After losing his publishing contract with Dea and Carter, Earle met producer Tony Brown and after severing his ties with Lomax and Epic Records obtained a seven-record deal with MCA Records.[11][12] Earle released his first full-length album, Guitar Town, on MCA Records in 1986. The title track became a Top Ten single in 1986 and his song "Goodbye's All We've Got Left" reached the Top Ten in 1987. That same year he released a compilation of earlier recordings, entitled Early Tracks, and an album with the Dukes, called Exit 0, which "received critical acclaim" for its blend of country and rock.[11]

Earle released Copperhead Road on Uni Records in 1988 which was characterized as "a quixotic project that mixed a lyrical folk tradition with hard rock and eclectic Irish influences such as The Pogues, who guested on the record".[12] The album's title track portrays a Vietnam veteran who uses his family background in running moonshine to become a marijuana grower/seller.[15] It was Earle's highest-peaking song to date in the United States and has sold 1.1 million digital copies there as of September 2017. Then Earle began "three years in a mysterious vaporization" according to the Chicago Sun-Times.[12]

His 1990 album The Hard Way[12] had a strong rock sound and was followed by "a shoddy live album" called Shut Up and Die Like an Aviator.[8][12] In August 1991, Earle appeared on the TV show The Texas Connection "looking pale and blown out".[12] In light of Earle's "increasing drug use", MCA Records did not renew his contract and Earle didn't record any music for the next four years.[8] By July 1993 Earle was reported to have regained his normal weight and had started to write new material.[12] At that time a writer for the Chicago Sun-Times called Earle "a visionary symbol of the New Traditionalist movement in country music."[12]

In 1994, two staff members at Warner/Chappell publishing company and Earle's former manager, John Dotson, created an in-house CD of Earle's songs entitled Uncut Gems and showcased it to some recording artists in Nashville. This resulted in several of Earle's songs being recorded by Travis Tritt, Stacy Dean Campbell and Robert Earl Keen.[8] After his recording hiatus, Earle released Train a Comin' on Winter Harvest Records and it was nominated for the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Folk Album in 1996. The album was characterized as a return to the "folksy acoustic" sound of his early career.[8]

In 1996, Earle formed his own record label, E-Squared Records, and released the album I Feel Alright, which combined the musical sounds of country, rock and rockabilly.[8] Earle released the album El Corazon (The Heart) in 1997 which one reviewer called "the capstone of this [Earle's] remarkable comeback".[16]

According to Earle, he wrote the song "Over Yonder" about a death row inmate with whom he exchanged letters before attending his execution in 1998.[17] He made a foray into bluegrass influenced music in 1999 when he released the album The Mountain with the Del McCoury Band. In 2000, Earle recorded his album Transcendental Blues,[8] which features the song "Galway Girl".

2000–present

[edit]Earle presented excerpts of his poetry and fiction writing at the 2000 New Yorker Festival.[8] His novel, I'll Never Get Out of This World Alive, was published in the spring of 2011 and a collection of short stories called Doghouse Roses followed that June.[18] Earle wrote and produced an off-Broadway play about the death of Karla Faye Tucker, the first woman executed since the death penalty was reinstated in Texas.[19]

In the early 2000s, Earle's album Jerusalem expressed his anti-war, anti-death penalty and his other "leftist views".[11][20] The album's song "John Walker's Blues", about the captured American Taliban fighter John Walker Lindh created controversy.[8][21] Earle responded by appearing on a variety of news and editorial programs and defended the song and his views on patriotism and terrorism.[8] His subsequent tour featured the Jerusalem album and was released as the live album Just an American Boy in 2003.[11]

In 2004, Earle released the album The Revolution Starts Now, a collection of songs influenced by the Iraq War and the policies of the George W. Bush administration and won a Grammy for best contemporary folk album.[11][20] The title song was used by General Motors in a TV advertisement.[22] The album was released during the U.S. presidential campaign.

The song "The Revolution Starts Now" was used in the promotional materials for Michael Moore's anti-war documentary film Fahrenheit 9/11 and appears on the album Songs and Artists That Inspired Fahrenheit 9/11.[citation needed] That year Earle was the subject of a documentary DVD called Just an American Boy.[23]

In 2006, Earle contributed a cover of Randy Newman's song "Rednecks" to the tribute album Sail Away: The Songs of Randy Newman.[24] Earle hosted a radio show on Air America from August 2004 until June 2007.[25] Later he began hosting a show called Hardcore Troubadour on the Outlaw Country channel.[26] Earle is also the subject of two biographies, Steve Earle: Fearless Heart, Outlaw Poet, by David McGee and Hardcore Troubadour: The Life and Near Death of Steve Earle by Lauren St John.[citation needed]

In September 2007, Earle released his twelfth studio album, Washington Square Serenade,[27] on New West Records. Earle recorded the album after relocating to New York City, and this was his first use of digital audio recording.[28] The album features Earle's then-wife, Allison Moorer, on "Days Aren't Long Enough" and "Down Here Below". The album includes Earle's version of Tom Waits' song "Way Down in the Hole" which was the theme song for the fifth season of the HBO series The Wire in which Earle appeared as a recovering drug addict and drug counselor named Walon (Earle's character appears in the first, fourth, and fifth seasons).[29] In 2008, Earle produced Joan Baez's album Day After Tomorrow.[30] Prior to their collaboration on Day After Tomorrow, Baez had covered two Earle songs, "Christmas in Washington" and "Jerusalem", on previous albums; "Jerusalem" had also become a staple of Baez' concerts. In the winter, he toured Europe and North America in support of Washington Square Serenade, performing both solo and with a disc jockey.[28]

On May 12, 2009, Earle released a tribute album, Townes, on New West Records. The album contained 15 songs written by Townes Van Zandt. Guest artists appearing on the album included Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine, Moorer, and his son Justin.[31] The album earned Earle a third Grammy award, again for best contemporary folk album.[20]

In 2010, Earle was awarded the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty's Shining Star of Abolition award.[32] Earle has recorded two other anti-death penalty songs: "Billy Austin", and "Ellis Unit One" for the 1995 film Dead Man Walking.[citation needed]

In 2010–2011, Earle appeared in seasons 1 and 2 of the HBO show Treme as Harley Wyatt, a talented street musician who mentors another character.

Earle released his first novel and fourteenth studio album, both titled I'll Never Get Out of This World Alive after a Hank Williams song, in the spring of 2011.[20] The album was produced by T Bone Burnett and deals with questions of mortality with a "more country" sound than his earlier work.[33] During the second half of his 2011 tour with The Dukes and Duchesses and Moorer, the drum kit was adorned with the slogan "we are the 99%" a reference to the Occupy movement of September 2011.[citation needed]

On February 17, 2015, Earle released his sixteenth studio album, Terraplane.[34][35]

On September 10, 2015, Earle & the Dukes released a new internet single titled "Mississippi, It's Time". The song's lyrics are directed towards the state of Mississippi and their refusal to abandon the Confederate Flag and remove it from their state flag. The song was released for sale the following day with all proceeds going towards the Southern Poverty Law Center, a civil rights organization.[36]

On June 10, 2016, Earle released an album of duets with Shawn Colvin, titled simply Colvin And Earle, which was accompanied by a tour in London and the US.[37][38]

On June 16, 2017, Earle & the Dukes released his seventeenth studio album, So You Wannabe An Outlaw. GUY, Earle's tribute album to his songwriting hero Guy Clark was released on March 29, 2019.[39]

Earle was among hundreds of artists whose material was destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire.[40] Earle was one of five artists who filed a class action lawsuit against Universal on June 21, in response to an earlier Times report on the fire.[41]

Earle was the musical director for the 2020 play Coal Country about the 2010 West Virginia mining disaster where 29 men died. The play by Jessica Blank and Eric Jensen ran at the Public Theater in New York and was cut short by the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. He was nominated for Drama Desk and Lucille Lortel awards for his work on the play's music. Songs from the play are on his 2020 album Ghosts of West Virginia.[42]

In June 2021 Earle joined Willie Nile on Nile's new song "Blood on Your Hands" to be featured on Nile's upcoming album The Day the Earth Stood Still.[43]

In 2023, Earle said he is working on a musical of the film Tender Mercies.[42]

Steve Earle features prominently in Love at the Five and Dime: The Songwriting Legacy of Nanci Griffith (Texas A&M University Press, 2024).

The Steve Earle Show

[edit]The Steve Earle Show (formerly known as The Revolution Starts Now) was a weekly radio show on the Air America Radio network hosted by Earle. It highlighted some of Earle's favorite artists, blending in-studio performances with liberal political talk and commentary. The show aired Sundays on some Air America affiliates from 10 to 11 PM ET. The show last aired on June 10, 2007, and that was a rebroadcast of a past episode.[44] Earle subsequently started DJing on a show on Sirius Satellite Radio called Hardcore Troubadour.[45]

Personal life

[edit]Earle has been married seven times, including twice to the same woman.[46] He married Sandra "Sandy" Henderson in Houston at the age of 18, but left her to move to Nashville a year later[11] where he met and married his second wife, Cynthia Dunn. Earle married his third wife, Carol-Ann Hunter, who was the mother of their son, singer-songwriter Justin Townes Earle (1982–2020).[11][47]

Next, he married Lou-Anne Gill (with whom he had a second son, Ian Dublin Earle, in January 1987). In December 1987, a groupie, Theresa Baker, claimed her daughter (Jessica Montana Baker) was fathered by Earle, though the initial DNA test was inconclusive and Earle did not submit to a second.[48][49] His fifth wife was Teresa Ensenat, an A&R executive for Geffen Records at the time.[12] He then married Lou-Anne Gill a second time, and finally, in 2005, he married singer-songwriter Allison Moorer with whom he had a third son, John Henry Earle, in April 2010.[50] John Henry was diagnosed with autism before age two. In March 2014, Earle announced that he and Moorer had separated.[51] Earle has primary custody of John Henry during the school year and then tours in the summer.[52] In an interview with The Guardian, Earle said about John Henry, "I know why I get up in the morning now: to figure out a way to make sure he's going to be alright when I’m gone. That's my job. That's what I do."[53]

In 1993, Earle was arrested for possession of heroin and in 1994, for cocaine and weapons possession.[8][54][55] A judge sentenced him to a year in jail after he admitted possession and failed to appear in court.[56] He was released from jail after serving 60 days of his sentence.[55][57] He then completed an outpatient drug treatment program at the Cedarwood Center in Hendersonville, Tennessee.[57] As a recovering heroin addict, Earle has used his experience in his songwriting.[58]

Earle's sister, Stacey Earle, is also a musician and songwriter.

Political views and activism

[edit]Earle is outspoken with his political views, and often addresses them in his lyrics and in interviews. Politically, he identifies as a socialist and tends to vote for Democratic candidates, despite not agreeing entirely with their politics.[59][60] During the 2016 election, he expressed support for Senator Bernie Sanders, whom he considered to have pushed Hillary Clinton to the left on important issues.[61] In a 2017 interview Earle said about President Donald Trump: "We've never had an orangutan in the White House before. There's a lot of 'What does this button do?' going on. It's scary. He really is a fascist. Whether he intended to be or not, he's a real live fascist."[62] However, Earle has called for the American left to engage with the concerns of working class Trump voters, saying in 2017: "…maybe that's one of the things we need to examine from my side because we're responsible. The left has lost touch with American people, and it's time to discuss that".[63] In 2020, he stated: "I thought that, given the way things are now, it was maybe my responsibility to make a record that spoke to and for people who didn't vote the way that I did. One of the dangers that we're in is if people like me keep thinking that everyone who voted for Trump is a racist or an asshole, then we're fucked, because it's simply not true."[63]

In his 1990 song "Justice in Ontario", Earle sang about the Port Hope 8 case. Earle criticized the conviction of six Satan's Choice bikers for a 1978 murder in Port Hope, arguing that the accused were innocent, framed by the ruthless Corporal Terry Hall of the Ontario Provincial Police's Special Squad.[64] In the song Earle compares the conviction of the "Port Hope 6" to the massacre of the Black Donnellys in 1880. In 1990, Earle stated in an interview about "Justice in Ontario": "There's some concern about reprisals because the O.P.P. (Ontario Provincial Police) is obviously not gonna be thrilled. My hope is that I'll be far too out-in-the-open and far too public for the police to do anything and get away with it. But the point is, that's not a reason for doing or not doing anything, because…I very nearly went to prison myself for something I didn't do, simply because a law enforcement agency didn't want to admit that somebody had fucked up—they didn't want to open the whole can of worms and all the other complaints that were constantly brought against the Dallas police department. You can't stand by and let stuff like that go down without saying anything about it. And I think I especially have a responsibility to do that, 'cause if I didn't have any money right now I'd be in prison in Texas—I'm convinced of that. It was that close. But I was able to afford decent legal representation. And it comes down to the fact that people who can't afford decent legal representation—who are subject to something like this happening and turning out very badly—feed my kids. That's where my money comes from and that's where my freedom comes from".[64]

In 2006, Earle, along with other artists, held a protest concert against the Iraq War.[65][66] Earle is a vocal opponent of capital punishment,[8] which he considers his primary area of political activism. Several of his songs have provided descriptions of the experiences of death row inmates, including "Billy Austin" and "Over Yonder (Jonathan's Song)".[15] Conversely, he has also written a song from the perspective of a prison guard working on death row in "Ellis Unit One", a song written for the film Dead Man Walking, the title based on the name of the State of Texas men's death row.[67] He is pro-choice and has argued that rich Americans have always had access to abortions; he says the political issue in the US is really whether poor women should have access. His 2012 novel I'll Never Get Out of This World Alive describes the life of a morphine-addicted doctor in 1963 San Antonio before Roe v. Wade who treats gunshot wounds and provides illegal abortions to poor women.[68] Since his youngest son was diagnosed with autism, Earle has also become an advocate for people on the autism spectrum.

Discography

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cross, Charles R. (August 9, 2017). "Steve Earle talks Seattle band Alice In Chains, Jimi Hendrix and food". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ^ Hattenstone, Simon (June 14, 2017). "Steve Earle: 'My wife left me for a younger, skinnier, less talented singer'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ^ Paul, John (June 23, 2017). "STEVE EARLE: SO YOU WANT TO BE AN OUTLAW". PopMatters. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ^ St John, Lauren. Hardcore Troubadour: The Life and Near Death of Steve Earle, Fourth Estate, 2002

- ^ Corn, David, "Death-House Troubadour: Steve Earle Rocks 'N' Rants against Capital Punishment", The Nation, Vol. 265, No. 6

- ^ Rose, Mike (January 17, 2023). "Today's famous birthdays list for January 17, 2023 includes celebrities James Earl Jones, Jim Carrey". Cleveland.com. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ a b Adams, Noah (June 29, 1999) Review: Steve Earle and the Del McCoury Band collaborate on "The Mountain", NPR's All Things Considered

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Steve Earle Bio MTV, retrieved July 28, 2012

- ^ Interview with Steve Earle, July 8, 92.1 KNBT's Friday Afternoon Club, Live from Gruene Hall in New Braunfels, Texas

- ^ Steve Earle Interview Part II (transcript) MEG. January 31, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Steve Earle Bio, AllMusic; retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hoekstra, Dave (July 11, 1993) "Steve Earle On the Road To Comeback", Chicago Sun-Times

- ^ a b c Ambrose, Patrick (April 24, 2012). "Politics as usual with Steve Earle". Creative Loafing Charlotte. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ Horowitz, Steve (October 9, 2011). "Connie Smith: Long Line of Heartaches". Pop Matters. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Inskeep, Steve (December 7, 2003) Interview: Steve Earle discusses the political nature of his songwriting, NPR Weekend Edition

- ^ Warren, Doug (November 20, 2007) "Steve Earle: El Corozon E-Squared/Warner Bros". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Earle, Steve (Sept 2000), "A Death in Texas", Tikkun, republished in Utne Reader, Jan–Feb 2001; retrieved September 5, 2012

- ^ Myth, reality and Steve Earle, Los Angeles Times; retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ Evans, Everett (October 30, 2005). "Steve Earle brings Karla Faye Tucker's life to the stage". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Steve Earle profile Archived July 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. 2012. biography.com. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ McGee, David. Steve Earle, Fearless Heart, Outlaw Poet. Backbeat: San Francisco, 2005, pg. 207.

- ^ "GM Commercial". cheezeball.net. Archived from the original on May 30, 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- ^ Begrand, Adrien (March 8, 2004) "Steve Earle: Just An American Boy", PopMatters, retrieved August 31, 2012

- ^ Song of the Day: Steve Earle, "Rednecks" (Randy Newman cover) » Cover Me. Covermesongs.com. Retrieved on May 10, 2012.

- ^ SteveEarle.net/radio, retrieved October 3, 2008

- ^ "Country Music Renegade Steve Earle to Launch a Weekly Show Exclusively on Sirius Satellite Radio" (Press release). Air America Radio. June 4, 2008. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ^ Cole, Katherine (December 15, 2007). "Steve Earle Gives Nod to New Hometown in 'Washington Square Serenade'". VOA News. Voice of America. Archived from the original on January 16, 2009. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ a b Schneider, Jason (2007). "Steve Earle – Washington Square Serenade". Exclaim!. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ^ "Walon Played by Steve Earle". HBO.com. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ Kintner, Thomas (September 9, 2008). "New on Disc: Jessica Simpson, Joan Baez". Hartford Courant. Retrieved September 15, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Blackstock, Peter, "Details on Steve Earle's album of Townes Van Zandt covers", NoDepression.com, March 9, 2009

- ^ "Steve Earle Lays It Down". Blackbookmag.com. January 27, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Graff, Gary (January 24, 2011) Steve Earle Explores Immortality On New Album Billboard, retrieved August 24, 2012

- ^ "Steve Earle to Release New Album in 2015". The Boot. December 10, 2014.

- ^ Waddell, Ray Steve Earle Explains Rock History, New Album 'Terraplane' and Heading Towards Broadway, Billboard.com, September 17, 2015.

- ^ "Hear Steve Earle Denounce Confederate Flag in 'Mississippi, It's Time'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ^ Green, Michelle (June 23, 2016). "Shawn Colvin and Steve Earle: Two Old Pals on the Road Together". New York Times. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Guarino, Mark (June 16, 2016). "Steve Earle and Shawn Colvin: nine divorces, two addictions, one perfect mix". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ^ "Steve Earle's New Album Pays Tribute To Guy Clark: 'The Greatest Story Songwriter That Ever Lived'". Wbur.org. March 28, 2019. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ Rosen, Jody (June 25, 2019). "Here Are Hundreds More Artists Whose Tapes Were Destroyed in the UMG Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (June 21, 2019). "Artists Sue Universal Music Group Over Losses in 2008 Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Nick Krewen (August 20, 2023). "'I just write, you know?' Steve Earle has songwriting down pat. Next, a TV pilot, two books and a Broadway musical". Toronto Star. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (June 7, 2021). "Willie Nile Taps Steve Earle for New Song 'Blood on Your Hands'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ SteveEarle.net/radio, retrieved 2008-10-03

- ^ "Country Music Renegade Steve Earle to Launch a Weekly Show Exclusively on Sirius Satellite Radio" (Press release). Air America Radio. June 4, 2008. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ^ St John, Lauren. Hardcore Troubadour: The Life and Near Death of Steve Earle, Fourth Estate, 2002.

- ^ "Singer Justin Townes Earle, Son of Musician Steve Earle, Dead at 38". People.com. August 23, 2020.

- ^ St John, Lauren. Hardcore Troubadour: The Life and Near Death of Steve Earle, Fourth Estate, 2002, p. 210

- ^ "RolandNote.com: The Ultimate Country Music Database". www.rolandnote.com. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ The Boot, April 7, 2010.

- ^ "Steve Earle On Staying Clean Through Personal Hardship". Themusic.com.au. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ Fuller, Eric. "Bruce Springsteen Plays Steve Earle's Autism Benefit Show In New York City. Love Fills The Room". Forbes. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ Hattenstone, Simon (June 14, 2017). "Steve Earle: 'My wife left me for a younger, skinnier, less talented singer'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ DeCurtis, Anthony (May 7, 2012). "Freeing A Mentor From His Mythology]". New York Times. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ a b Bledsoe, Wayne (January 14, 1996) STEVE EARLE KEEPS ON MAKING MUSIC ON HIS OWN TERMS, Albany Times Union (Albany, New York); accessed August 11, 2017.

- ^ EARLE TREATMENT, The Buffalo News (Buffalo, New York). September 9, 1994.

- ^ a b EARLE MOVED TO DRUG CENTER, The Buffalo News (Buffalo, New York). November 3, 1994.

- ^ Thomas, Stephen (September 11, 2001). "Yahoo Biography". Yahoo! Music. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ "Goodbye Guitar Town: An Interview with Steve Earle". PopMatters. September 23, 2007. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ Ian Bruce (August 7, 2002). "US country singer Steve Earle subjected to witch-hunt". Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ Eric Alterman (March 19, 2015). "Interview With Steve Earle". The Nation. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ Betts, Stephen (August 17, 2017). "Steve Earle talks outlaws, Guy Clark and Donald Trump". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ a b "Socialist Steve Earle: Stop Demonizing Trump Supporters". Hollywood in Toto. February 29, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Newton, Steve (October 11, 1990). "25 years ago: Steve Earle talks bikers, executions, and "Justice in Ontario"". The Georgia Straight. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ "Against the War, Michael Stipe, Steve Earle and Lots of Others". New York Times. March 22, 2006.

- ^ "Anti-War Benefit Concert". CBS News. March 21, 2006.

- ^ "Dead Man Walking" Ambles Away With Year's Top Singles Los Angeles Times. December 28, 1996.

- ^ "Politics as usual with Steve Earle". Creative Loafing Charlotte. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Schone, Mark. (1998). "Steve Earle". In The Encyclopedia of Country Music. Paul Kingsbury, Ed. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 160–1.

- St John, Lauren. Hardcore Troubadour: The Life and Near Death of Steve Earle, Fourth Estate, 2002 ISBN 1-84115-611-6

- McGee, David. Steve Earle, Fearless Heart, Outlaw Poet. Backbeat: San Francisco, 2005

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (July 2024) |

- 1955 births

- 20th-century American guitarists

- 20th-century American male musicians

- Activists from Texas

- American alternative country singers

- American abortion-rights activists

- American anti-war activists

- American anti–death penalty activists

- American country guitarists

- American country rock singers

- American country singer-songwriters

- American folk guitarists

- American folk rock musicians

- American male guitarists

- American male singer-songwriters

- American mandolinists

- American rock guitarists

- Autism activists

- Country musicians from Texas

- Earle musical family

- Fantasy Records artists

- Geffen Records artists

- Grammy Award winners

- Guitarists from Texas

- Living people

- MCA Records artists

- Musicians from Hampton, Virginia

- Musicians from Houston

- Musicians from San Antonio

- New West Records artists

- Rykodisc artists

- Singer-songwriters from Texas

- Singer-songwriters from Virginia

- Stony Plain Records artists

- Texas socialists

- Uni Records artists