Diesel engine

| Diesel engine | |

|---|---|

Diesel engine built by Langen & Wolf under licence, 1898 | |

| Classification | Internal combustion engine |

| Industry | Automotive |

| Application | Energy transformation |

| Inventor | Rudolf Diesel |

| Invented | 1893 |

The diesel engine, named after the German engineer Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which ignition of the fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to mechanical compression; thus, the diesel engine is called a compression-ignition engine (CI engine). This contrasts with engines using spark plug-ignition of the air-fuel mixture, such as a petrol engine (gasoline engine) or a gas engine (using a gaseous fuel like natural gas or liquefied petroleum gas).

Introduction

[edit]Diesel engines work by compressing only air, or air combined with residual combustion gases from the exhaust (known as exhaust gas recirculation, "EGR"). Air is inducted into the chamber during the intake stroke, and compressed during the compression stroke. This increases air temperature inside the cylinder so that atomised diesel fuel injected into the combustion chamber ignites. With the fuel being injected into the air just before combustion, the dispersion of fuel is uneven; this is called a heterogeneous air-fuel mixture. The torque a diesel engine produces is controlled by manipulating the air-fuel ratio (λ); instead of throttling the intake air, the diesel engine relies on altering the amount of fuel that is injected, and thus the air-fuel ratio is usually high.

The diesel engine has the highest thermal efficiency (see engine efficiency) of any practical internal or external combustion engine due to its very high expansion ratio and inherent lean burn, which enables heat dissipation by excess air. A small efficiency loss is also avoided compared with non-direct-injection gasoline engines, as unburned fuel is not present during valve overlap, and therefore no fuel goes directly from the intake/injection to the exhaust. Low-speed diesel engines (as used in ships and other applications where overall engine weight is relatively unimportant) can reach effective efficiencies of up to 55%.[1] The combined cycle gas turbine (Brayton and Rankine cycle) is a combustion engine that is more efficient than a diesel engine, but due to its mass and dimensions, is unsuitable for many vehicles, including watercraft and some aircraft. The world's largest diesel engines put in service are 14-cylinder, two-stroke marine diesel engines; they produce a peak power of almost 100 MW each.[2]

Diesel engines may be designed with either two-stroke or four-stroke combustion cycles. They were originally used as a more efficient replacement for stationary steam engines. Since the 1910s, they have been used in submarines and ships. Use in locomotives, buses, trucks, heavy equipment, agricultural equipment and electricity generation plants followed later. In the 1930s, they slowly began to be used in some automobiles. Since the 1970s energy crisis, demand for higher fuel efficiency has resulted in most major automakers, at some point, offering diesel-powered models, even in very small cars.[3][4] According to Konrad Reif (2012), the EU average for diesel cars at the time accounted for half of newly registered cars.[5] However, air pollution and overall emissions are more difficult to control in diesel engines compared to gasoline engines, and the use of diesel auto engines in the U.S. is now largely relegated to larger on-road and off-road vehicles.[6][7]

Though aviation has traditionally avoided using diesel engines, aircraft diesel engines have become increasingly available in the 21st century. Since the late 1990s, for various reasons—including the diesel's inherent advantages over gasoline engines, but also for recent issues peculiar to aviation—development and production of diesel engines for aircraft has surged, with over 5,000 such engines delivered worldwide between 2002 and 2018, particularly for light airplanes and unmanned aerial vehicles.[8][9]

History

[edit]Diesel's idea

[edit]

Effective efficiency 16.6%

Fuel consumption 519 g·kW−1·h−1

Rated power 13.1 kW

Effective efficiency 26.2%

Fuel consumption 324 g·kW−1·h−1.

In 1878, Rudolf Diesel, who was a student at the "Polytechnikum" in Munich, attended the lectures of Carl von Linde. Linde explained that steam engines are capable of converting just 6–10% of the heat energy into work, but that the Carnot cycle allows conversion of much more of the heat energy into work by means of isothermal change in condition. According to Diesel, this ignited the idea of creating a highly efficient engine that could work on the Carnot cycle.[14] Diesel was also introduced to a fire piston, a traditional fire starter using rapid adiabatic compression principles which Linde had acquired from Southeast Asia.[15] After several years of working on his ideas, Diesel published them in 1893 in the essay Theory and Construction of a Rational Heat Motor.[14]

Diesel was heavily criticised for his essay, but only a few found the mistake that he made;[16] his rational heat motor was supposed to utilise a constant temperature cycle (with isothermal compression) that would require a much higher level of compression than that needed for compression ignition. Diesel's idea was to compress the air so tightly that the temperature of the air would exceed that of combustion. However, such an engine could never perform any usable work.[17][18][19] In his 1892 US patent (granted in 1895) #542846, Diesel describes the compression required for his cycle:

- pure atmospheric air is compressed, according to curve 1 2, to such a degree that, before ignition or combustion takes place, the highest pressure of the diagram and the highest temperature are obtained-that is to say, the temperature at which the subsequent combustion has to take place, not the burning or igniting point. To make this more clear, let it be assumed that the subsequent combustion shall take place at a temperature of 700°. Then in that case the initial pressure must be sixty-four atmospheres, or for 800° centigrade the pressure must be ninety atmospheres, and so on. Into the air thus compressed is then gradually introduced from the exterior finely divided fuel, which ignites on introduction, since the air is at a temperature far above the igniting-point of the fuel. The characteristic features of the cycle according to my present invention are therefore, increase of pressure and temperature up to the maximum, not by combustion, but prior to combustion by mechanical compression of air, and there upon the subsequent performance of work without increase of pressure and temperature by gradual combustion during a prescribed part of the stroke determined by the cut-oil.[20]

By June 1893, Diesel had realised his original cycle would not work, and he adopted the constant pressure cycle.[21] Diesel describes the cycle in his 1895 patent application. Notice that there is no longer a mention of compression temperatures exceeding the temperature of combustion. Now it is simply stated that the compression must be sufficient to trigger ignition.

- 1. In an internal-combustion engine, the combination of a cylinder and piston constructed and arranged to compress air to a degree producing a temperature above the igniting-point of the fuel, a supply for compressed air or gas; a fuel-supply; a distributing-valve for fuel, a passage from the air supply to the cylinder in communication with the fuel-distributing valve, an inlet to the cylinder in communication with the air-supply and with the fuel-valve, and a cut-oil, substantially as described.[22][23][24]

In 1892, Diesel received patents in Germany, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States for "Method of and Apparatus for Converting Heat into Work".[25] In 1894 and 1895, he filed patents and addenda in various countries for his engine; the first patents were issued in Spain (No. 16,654),[26] France (No. 243,531) and Belgium (No. 113,139) in December 1894, and in Germany (No. 86,633) in 1895 and the United States (No. 608,845) in 1898.[27]

Diesel was attacked and criticised over several years. Critics claimed that Diesel never invented a new motor and that the invention of the diesel engine is fraud. Otto Köhler and Emil Capitaine were two of the most prominent critics of Diesel's time.[28] Köhler had published an essay in 1887, in which he describes an engine similar to the engine Diesel describes in his 1893 essay. Köhler figured that such an engine could not perform any work.[19][29] Emil Capitaine had built a petroleum engine with glow-tube ignition in the early 1890s;[30] he claimed against his own better judgement that his glow-tube ignition engine worked the same way Diesel's engine did. His claims were unfounded and he lost a patent lawsuit against Diesel.[31] Other engines, such as the Akroyd engine and the Brayton engine, also use an operating cycle that is different from the diesel engine cycle.[29][32] Friedrich Sass says that the diesel engine is Diesel's "very own work" and that any "Diesel myth" is "falsification of history".[33]

The first diesel engine

[edit]Diesel sought out firms and factories that would build his engine. With the help of Moritz Schröter and Max Gutermuth,[34] he succeeded in convincing both Krupp in Essen and the Maschinenfabrik Augsburg.[35] Contracts were signed in April 1893,[36] and in early summer 1893, Diesel's first prototype engine was built in Augsburg. On 10 August 1893, the first ignition took place, the fuel used was petrol. In winter 1893/1894, Diesel redesigned the existing engine, and by 18 January 1894, his mechanics had converted it into the second prototype.[37] During January that year, an air-blast injection system was added to the engine's cylinder head and tested.[38] Friedrich Sass argues that, it can be presumed that Diesel copied the concept of air-blast injection from George B. Brayton,[32] albeit that Diesel substantially improved the system.[39] On 17 February 1894, the redesigned engine ran for 88 revolutions – one minute;[10] with this news, Maschinenfabrik Augsburg's stock rose by 30%, indicative of the tremendous anticipated demands for a more efficient engine.[40] On 26 June 1895, the engine achieved an effective efficiency of 16.6% and had a fuel consumption of 519 g·kW−1·h−1. [41] However, despite proving the concept, the engine caused problems,[42] and Diesel could not achieve any substantial progress.[43] Therefore, Krupp considered rescinding the contract they had made with Diesel.[44] Diesel was forced to improve the design of his engine and rushed to construct a third prototype engine. Between 8 November and 20 December 1895, the second prototype had successfully covered over 111 hours on the test bench. In the January 1896 report, this was considered a success.[45]

In February 1896, Diesel considered supercharging the third prototype.[46] Imanuel Lauster, who was ordered to draw the third prototype "Motor 250/400", had finished the drawings by 30 April 1896. During summer that year the engine was built, it was completed on 6 October 1896.[47] Tests were conducted until early 1897.[48] First public tests began on 1 February 1897.[49] Moritz Schröter's test on 17 February 1897 was the main test of Diesel's engine. The engine was rated 13.1 kW with a specific fuel consumption of 324 g·kW−1·h−1,[50] resulting in an effective efficiency of 26.2%.[51][52] By 1898, Diesel had become a millionaire.[53]

Timeline

[edit]1890s

[edit]- 1893: Rudolf Diesel's essay titled Theory and Construction of a Rational Heat Motor appears.[54][55]

- 1893: February 21, Diesel and the Maschinenfabrik Augsburg sign a contract that allows Diesel to build a prototype engine.[56]

- 1893: February 23, Diesel obtains a patent (RP 67207) titled "Arbeitsverfahren und Ausführungsart für Verbrennungsmaschinen" (Working Methods and Techniques for Internal Combustion Engines).

- 1893: April 10, Diesel and Krupp sign a contract that allows Diesel to build a prototype engine.[56]

- 1893: April 24, both Krupp and the Maschinenfabrik Augsburg decide to collaborate and build just a single prototype in Augsburg.[56][36]

- 1893: July, the first prototype is completed.[57]

- 1893: August 10, Diesel injects fuel (petrol) for the first time, resulting in combustion, destroying the indicator.[58]

- 1893: November 30, Diesel applies for a patent (RP 82168) for a modified combustion process. He obtains it on 12 July 1895.[59][60][61]

- 1894: January 18, after the first prototype was modified to become the second prototype, testing with the second prototype begins.[37]

- 1894: February 17, The second prototype runs for the first time.[10]

- 1895: March 30, Diesel applies for a patent (RP 86633) for a starting process with compressed air.[62]

- 1895: June 26, the second prototype passes brake testing for the first time.[41]

- 1895: Diesel applies for a second patent US Patent # 608845[63]

- 1895: November 8 – December 20, a series of tests with the second prototype is conducted. In total, 111 operating hours are recorded.[45]

- 1896: April 30, Imanuel Lauster completes the third and final prototype's drawings.[47]

- 1896: October 6, the third and final prototype engine is completed.[11]

- 1897: February 1, Diesel's prototype engine is running and finally ready for efficiency testing and production.[49]

- 1897: October 9, Adolphus Busch licenses rights to the diesel engine for the US and Canada.[53][64]

- 1897: 29 October, Rudolf Diesel obtains a patent (DRP 95680) on supercharging the diesel engine.[46]

- 1898: February 1, the Diesel Motoren-Fabrik Actien-Gesellschaft is registered.[65]

- 1898: March, the first commercial diesel engine, rated 2×30 PS (2×22 kW), is installed in the Kempten plant of the Vereinigte Zündholzfabriken A.G.[66][67]

- 1898: September 17, the Allgemeine Gesellschaft für Dieselmotoren A.-G. is founded.[68]

- 1899: The first two-stroke diesel engine, invented by Hugo Güldner, is built.[52]

1900s

[edit]

- 1901: Imanuel Lauster designs the first trunk piston diesel engine (DM 70).[69]

- 1901: By 1901, MAN had produced 77 diesel engine cylinders for commercial use.[70]

- 1903: Two first diesel-powered ships are launched, both for river and canal operations: The Vandal naphtha tanker and the Sarmat.[71]

- 1904: The French launch the first diesel submarine, the Aigrette.[72]

- 1905: January 14: Diesel applies for a patent on unit injection (L20510I/46a).[73]

- 1905: The first diesel engine turbochargers and intercoolers are manufactured by Büchi.[74]

- 1906: The Diesel Motoren-Fabrik Actien-Gesellschaft is dissolved.[28]

- 1908: Diesel's patents expire.[75]

- 1908: The first lorry (truck) with a diesel engine appears.[76]

- 1909: March 14, Prosper L'Orange applies for a patent on precombustion chamber injection.[77] He later builds the first diesel engine with this system.[78][79]

1910s

[edit]- 1910: MAN starts making two-stroke diesel engines.[80]

- 1910: November 26, James McKechnie applies for a patent on unit injection.[81] Unlike Diesel, he successfully built working unit injectors.[73][82]

- 1911: November 27, the Allgemeine Gesellschaft für Dieselmotoren A.-G. is dissolved.[65]

- 1911: The Germania shipyard in Kiel builds 850 PS (625 kW) diesel engines for German submarines. These engines are installed in 1914.[83]

- 1912: MAN builds the first double-acting piston two-stroke diesel engine.[84]

- 1912: The first locomotive with a diesel engine is used on the Swiss Winterthur–Romanshorn railway.[85]

- 1912: MS Selandia is the first ocean-going ship with diesel engines.[86]

- 1913: NELSECO diesels are installed on commercial ships and US Navy submarines.[87]

- 1913: September 29, Rudolf Diesel dies mysteriously while crossing the English Channel on SS Dresden.[88]

- 1914: MAN builds 900 PS (662 kW) two-stroke engines for Dutch submarines.[89]

- 1919: Prosper L'Orange obtains a patent on a precombustion chamber insert incorporating a needle injection nozzle.[90][91][79] First diesel engine from Cummins.[92][93]

1920s

[edit]

- 1923: At the Königsberg DLG exhibition, the first agricultural tractor with a diesel engine, the prototype Benz-Sendling S6, is presented.[94][better source needed]

- 1923: December 15, the first lorry with a direct-injected diesel engine is tested by MAN. The same year, Benz builds a lorry with a pre-combustion chamber injected diesel engine.[95]

- 1923: The first two-stroke diesel engine with counterflow scavenging appears.[96]

- 1924: Fairbanks-Morse introduces the two-stroke Y-VA (later renamed to Model 32).[97]

- 1925: Sendling starts mass-producing a diesel-powered agricultural tractor.[98]

- 1927: Bosch introduces the first inline injection pump for motor vehicle diesel engines.[99]

- 1929: The first passenger car with a diesel engine appears. Its engine is an Otto engine modified to use the diesel principle and Bosch's injection pump. Several other diesel car prototypes follow.[100]

1930s

[edit]- 1933: Junkers Motorenwerke in Germany start production of the most successful mass-produced aviation diesel engine of all time, the Jumo 205. By the outbreak of World War II, over 900 examples are produced. Its rated take-off power is 645 kW.[101]

- 1933: General Motors uses its new roots-blown, unit-injected two-stroke Winton 201A diesel engine to power its automotive assembly exhibit at the Chicago World's Fair (A Century of Progress).[102] The engine is offered in several versions ranging from 600–900 hp (447–671 kW).[103]

- 1934: The Budd Company builds the first diesel–electric passenger train in the US, the Pioneer Zephyr 9900, using a Winton engine.[102]

- 1935: The Citroën Rosalie is fitted with an early swirl chamber injected diesel engine for testing purposes.[104] Daimler-Benz starts manufacturing the Mercedes-Benz OM 138, the first mass-produced diesel engine for passenger cars, and one of the few marketable passenger car diesel engines of its time. It is rated 45 PS (33 kW).[105]

- 1936: March 4, the airship LZ 129 Hindenburg, the biggest aircraft ever made, takes off for the first time. It is powered by four V16 Daimler-Benz LOF 6 diesel engines, rated 1,200 PS (883 kW) each.[106]

- 1936: Manufacture of the first mass-produced passenger car with a diesel engine (Mercedes-Benz 260 D) begins.[100]

- 1937: Konstantin Fyodorovich Chelpan develops the V-2 diesel engine, later used in the Soviet T-34 tanks, widely regarded as the best tank chassis of World War II.[107]

- 1938: General Motors forms the GM Diesel Division, later to become Detroit Diesel, and introduces the Series 71 inline high-speed medium-horsepower two-stroke engine, suitable for road vehicles and marine use.[108]

1940s

[edit]- 1946: Clessie Cummins obtains a patent on a fuel feeding and injection apparatus for oil-burning engines that incorporates separate components for generating injection pressure and injection timing.[109]

- 1946: Klöckner-Humboldt-Deutz (KHD) introduces an air-cooled mass-production diesel engine to the market.[110]

1950s

[edit]

- 1950s: KHD becomes the air-cooled diesel engine global market leader.[111]

- 1951: J. Siegfried Meurer obtains a patent on the M-System, a design that incorporates a central sphere combustion chamber in the piston (DBP 865683).[112]

- 1953: First mass-produced swirl chamber injected passenger car diesel engine (Borgward/Fiat).[81]

- 1954: Daimler-Benz introduces the Mercedes-Benz OM 312 A, a 4.6 litre straight-6 series-production industrial diesel engine with a turbocharger, rated 115 PS (85 kW). It proves to be unreliable.[113]

- 1954: Volvo produces a small batch series of 200 units of a turbocharged version of the TD 96 engine. This 9.6 litre engine is rated 136 kW (185 PS).[114]

- 1955: Turbocharging for MAN two-stroke marine diesel engines becomes standard.[96]

- 1959: The Peugeot 403 becomes the first mass-produced passenger sedan/saloon manufactured outside West Germany to be offered with a diesel engine option.[115]

1960s

[edit]

- 1964: Summer, Daimler-Benz switches from precombustion chamber injection to helix-controlled direct injection.[117][112]

- 1962–65: A diesel compression braking system, eventually to be manufactured by the Jacobs Manufacturing Company and nicknamed the "Jake Brake", is invented and patented by Clessie Cummins.[118]

1970s

[edit]- 1972: KHD introduces the AD-System, Allstoff-Direkteinspritzung, (anyfuel direct-injection), for its diesel engines. AD-diesels can operate on virtually any kind of liquid fuel, but they are fitted with an auxiliary spark plug that fires if the ignition quality of the fuel is too low.[119]

- 1976: Development of the common rail injection begins at the ETH Zürich.[120]

- 1976: The Volkswagen Golf becomes the first compact passenger sedan/saloon to be offered with a diesel engine option.[121][122]

- 1978: Daimler-Benz produces the first passenger car diesel engine with a turbocharger (Mercedes-Benz OM617 engine).[123]

- 1979: First prototype of a low-speed two-stroke crosshead engine with common rail injection.[124]

1980s

[edit]- 1981/82: Uniflow scavenging for two-stroke marine diesel engines becomes standard.[125]

- 1982: August, Toyota introduces a microprocessor-controlled engine control unit (ECU) for Diesel engines to the Japanese market.[126]

- 1985: December, road testing of a common rail injection system for lorries using a modified 6VD 12,5/12 GRF-E engine in an IFA W50 takes place.[127]

- 1987: Daimler-Benz introduces the electronically controlled injection pump for lorry diesel engines.[81]

- 1988: The Fiat Croma becomes the first mass-produced passenger car in the world to have a direct injected diesel engine.[81]

- 1989: The Audi 100 is the first passenger car in the world with a turbocharged, intercooled, direct-injected, and electronically controlled diesel engine.[81] It has a BMEP of 1.35 MPa and a BSFC of 198 g/(kW·h).[128]

1990s

[edit]- 1992: 1 July, the Euro 1 emission standard comes into effect.[129]

- 1993: First passenger car diesel engine with four valves per cylinder, the Mercedes-Benz OM 604.[123]

- 1994: Unit injector system by Bosch for lorry diesel engines.[130]

- 1996: First diesel engine with direct injection and four valves per cylinder, used in the Opel Vectra.[131][81]

- 1996: First radial piston distributor injection pump by Bosch.[130]

- 1997: First mass-produced common rail diesel engine for a passenger car, the Fiat 1.9 JTD.[81][123]

- 1998: BMW wins the 24 Hours Nürburgring race with a modified BMW E36. The car, called 320d, is powered by a 2-litre, straight-four diesel engine with direct injection and a helix-controlled distributor injection pump (Bosch VP 44), producing 180 kW (240 hp). The fuel consumption is 23 L/100 km, only half the fuel consumption of a similar Otto-powered car.[132]

- 1998: Volkswagen introduces the VW EA188 Pumpe-Düse engine (1.9 TDI), with Bosch-developed electronically controlled unit injectors.[123]

- 1999: Daimler-Chrysler presents the first common rail three-cylinder diesel engine used in a passenger car (the Smart City Coupé).[81]

2000s

[edit]

- 2000: Peugeot introduces the diesel particulate filter for passenger cars.[81][123]

- 2002: Piezoelectric injector technology by Siemens.[133]

- 2003: Piezoelectric injector technology by Bosch,[134] and Delphi.[135]

- 2004: BMW introduces dual-stage turbocharging with the BMW M57 engine.[123]

- 2006: The world's most powerful diesel engine, the Wärtsilä-Sulzer RTA96-C, is produced. It is rated 80,080 kW.[136]

- 2006: Audi R10 TDI, equipped with a 5.5-litre V12-TDI engine, rated 476 kW (638 hp), wins the 2006 24 Hours of Le Mans.[81]

- 2006: Daimler-Chrysler launches the first series-production passenger car engine with selective catalytic reduction exhaust gas treatment, the Mercedes-Benz OM 642. It is fully complying with the Tier2Bin8 emission standard.[123]

- 2008: Volkswagen introduces the LNT catalyst for passenger car diesel engines with the VW 2.0 TDI engine.[123]

- 2008: Volkswagen starts series production of the biggest passenger car diesel engine, the Audi 6-litre V12 TDI.[123]

- 2008: Subaru introduces the first horizontally opposed diesel engine to be fitted to a passenger car. It is a 2-litre common rail engine, rated 110 kW.[137]

2010s

[edit]- 2010: Mitsubishi developed and started mass production of its 4N13 1.8 L DOHC I4, the world's first passenger car diesel engine that features a variable valve timing system.[138]

- 2012: BMW introduces dual-stage turbocharging with three turbochargers for the BMW N57 engine.[123]

- 2015: Common rail systems working with pressures of 2,500 bar launched.[81]

- 2015: In the Volkswagen emissions scandal, the US EPA issued a notice of violation of the Clean Air Act to Volkswagen Group after it was found that Volkswagen had intentionally programmed turbocharged direct injection (TDI) diesel engines to activate certain emissions controls only during laboratory emissions testing.[139][140][141][142]

Operating principle

[edit]Overview

[edit]The characteristics of a diesel engine are[143]

- Use of compression ignition, instead of an ignition apparatus such as a spark plug.

- Internal mixture formation. In diesel engines, the mixture of air and fuel is only formed inside the combustion chamber.

- Quality torque control. The amount of torque a diesel engine produces is not controlled by throttling the intake air (unlike a traditional spark-ignition petrol engine, where the airflow is reduced in order to regulate the torque output), instead, the volume of air entering the engine is maximised at all times, and the torque output is regulated solely by controlling the amount of injected fuel.

- High air-fuel ratio. Diesel engines run at global air-fuel ratios significantly leaner than the stoichiometric ratio.

- Diffusion flame: At combustion, oxygen first has to diffuse into the flame, rather than having oxygen and fuel already mixed before combustion, which would result in a premixed flame.

- Heterogeneous air-fuel mixture: In diesel engines, there is no even dispersion of fuel and air inside the cylinder. That is because the combustion process begins at the end of the injection phase, before a homogeneous mixture of air and fuel can be formed.

- Preference for the fuel to have a high ignition performance (Cetane number), rather than a high knocking resistance (octane rating) that is preferred for petrol engines.

Thermodynamic cycle

[edit]This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. (July 2022) |

The diesel internal combustion engine differs from the gasoline powered Otto cycle by using highly compressed hot air to ignite the fuel rather than using a spark plug (compression ignition rather than spark ignition).

In the diesel engine, only air is initially introduced into the combustion chamber. The air is then compressed with a compression ratio typically between 15:1 and 23:1. This high compression causes the temperature of the air to rise. At about the top of the compression stroke, fuel is injected directly into the compressed air in the combustion chamber. This may be into a (typically toroidal) void in the top of the piston or a pre-chamber depending upon the design of the engine. The fuel injector ensures that the fuel is broken down into small droplets, and that the fuel is distributed evenly. The heat of the compressed air vaporises fuel from the surface of the droplets. The vapour is then ignited by the heat from the compressed air in the combustion chamber, the droplets continue to vaporise from their surfaces and burn, getting smaller, until all the fuel in the droplets has been burnt. Combustion occurs at a substantially constant pressure during the initial part of the power stroke. The start of vaporisation causes a delay before ignition and the characteristic diesel knocking sound as the vapour reaches ignition temperature and causes an abrupt increase in pressure above the piston (not shown on the P-V indicator diagram). When combustion is complete the combustion gases expand as the piston descends further; the high pressure in the cylinder drives the piston downward, supplying power to the crankshaft.

As well as the high level of compression allowing combustion to take place without a separate ignition system, a high compression ratio greatly increases the engine's efficiency. Increasing the compression ratio in a spark-ignition engine where fuel and air are mixed before entry to the cylinder is limited by the need to prevent pre-ignition, which would cause engine damage. Since only air is compressed in a diesel engine, and fuel is not introduced into the cylinder until shortly before top dead centre (TDC), premature detonation is not a problem and compression ratios are much higher.

The pressure–volume diagram (pV) diagram is a simplified and idealised representation of the events involved in a diesel engine cycle, arranged to illustrate the similarity with a Carnot cycle. Starting at 1, the piston is at bottom dead centre and both valves are closed at the start of the compression stroke; the cylinder contains air at atmospheric pressure. Between 1 and 2 the air is compressed adiabatically – that is without heat transfer to or from the environment – by the rising piston. (This is only approximately true since there will be some heat exchange with the cylinder walls.) During this compression, the volume is reduced, the pressure and temperature both rise. At or slightly before 2 (TDC) fuel is injected and burns in the compressed hot air. Chemical energy is released and this constitutes an injection of thermal energy (heat) into the compressed gas. Combustion and heating occur between 2 and 3. In this interval the pressure remains constant since the piston descends, and the volume increases; the temperature rises as a consequence of the energy of combustion. At 3 fuel injection and combustion are complete, and the cylinder contains gas at a higher temperature than at 2. Between 3 and 4 this hot gas expands, again approximately adiabatically. Work is done on the system to which the engine is connected. During this expansion phase the volume of the gas rises, and its temperature and pressure both fall. At 4 the exhaust valve opens, and the pressure falls abruptly to atmospheric (approximately). This is unresisted expansion and no useful work is done by it. Ideally the adiabatic expansion should continue, extending the line 3–4 to the right until the pressure falls to that of the surrounding air, but the loss of efficiency caused by this unresisted expansion is justified by the practical difficulties involved in recovering it (the engine would have to be much larger). After the opening of the exhaust valve, the exhaust stroke follows, but this (and the following induction stroke) are not shown on the diagram. If shown, they would be represented by a low-pressure loop at the bottom of the diagram. At 1 it is assumed that the exhaust and induction strokes have been completed, and the cylinder is again filled with air. The piston-cylinder system absorbs energy between 1 and 2 – this is the work needed to compress the air in the cylinder, and is provided by mechanical kinetic energy stored in the flywheel of the engine. Work output is done by the piston-cylinder combination between 2 and 4. The difference between these two increments of work is the indicated work output per cycle, and is represented by the area enclosed by the pV loop. The adiabatic expansion is in a higher pressure range than that of the compression because the gas in the cylinder is hotter during expansion than during compression. It is for this reason that the loop has a finite area, and the net output of work during a cycle is positive.[144]

Efficiency

[edit]The fuel efficiency of diesel engines is better than most other types of combustion engines,[145][146] due to their high compression ratio, high air–fuel equivalence ratio (λ),[147] and the lack of intake air restrictions (i.e. throttle valves). Theoretically, the highest possible efficiency for a diesel engine is 75%.[148] However, in practice the efficiency is much lower, with efficiencies of up to 43% for passenger car engines,[149] up to 45% for large truck and bus engines, and up to 55% for large two-stroke marine engines.[1][150] The average efficiency over a motor vehicle driving cycle is lower than the diesel engine's peak efficiency (for example, a 37% average efficiency for an engine with a peak efficiency of 44%).[151] That is because the fuel efficiency of a diesel engine drops at lower loads, however, it does not drop quite as fast as the Otto (spark ignition) engine's.[152]

Emissions

[edit]Diesel engines are combustion engines and, therefore, emit combustion products in their exhaust gas. Due to incomplete combustion,[153] diesel engine exhaust gases include carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, particulate matter, and nitrogen oxides pollutants. About 90 per cent of the pollutants can be removed from the exhaust gas using exhaust gas treatment technology.[154][155] Road vehicle diesel engines have no sulfur dioxide emissions, because motor vehicle diesel fuel has been sulfur-free since 2003.[156] Helmut Tschöke argues that particulate matter emitted from motor vehicles has negative impacts on human health.[157]

The particulate matter in diesel exhaust emissions is sometimes classified as a carcinogen or "probable carcinogen" and is known to increase the risk of heart and respiratory diseases.[158]

Electrical system

[edit]In principle, a diesel engine does not require any sort of electrical system. However, most modern diesel engines are equipped with an electrical fuel pump, and an electronic engine control unit.

However, there is no high-voltage electrical ignition system present in a diesel engine. This eliminates a source of radio frequency emissions (which can interfere with navigation and communication equipment), which is why only diesel-powered vehicles are allowed in some parts of the American National Radio Quiet Zone.[159]

Torque control

[edit]To control the torque output at any given time (i.e. when the driver of a car adjusts the accelerator pedal), a governor adjusts the amount of fuel injected into the engine. Mechanical governors have been used in the past, however electronic governors are more common on modern engines. Mechanical governors are usually driven by the engine's accessory belt or a gear-drive system[160][161] and use a combination of springs and weights to control fuel delivery relative to both load and speed.[160] Electronically governed engines use an electronic control unit (ECU) or electronic control module (ECM) to control the fuel delivery. The ECM/ECU uses various sensors (such as engine speed signal, intake manifold pressure and fuel temperature) to determine the amount of fuel injected into the engine.

Due to the amount of air being constant (for a given RPM) while the amount of fuel varies, very high ("lean") air-fuel ratios are used in situations where minimal torque output is required. This differs from a petrol engine, where a throttle is used to also reduce the amount of intake air as part of regulating the engine's torque output. Controlling the timing of the start of injection of fuel into the cylinder is similar to controlling the ignition timing in a petrol engine. It is therefore a key factor in controlling the power output, fuel consumption and exhaust emissions.

Classification

[edit]There are several different ways of categorising diesel engines, as outlined in the following sections.

RPM operating range

[edit]Günter Mau categorises diesel engines by their rotational speeds into three groups:[162]

- High-speed engines (> 1,000 rpm),

- Medium-speed engines (300–1,000 rpm), and

- Slow-speed engines (< 300 rpm).

- High-speed diesel engines

High-speed engines are used to power trucks (lorries), buses, tractors, cars, yachts, compressors, pumps and small electrical generators.[163] As of 2018, most high-speed engines have direct injection. Many modern engines, particularly in on-highway applications, have common rail direct injection.[164] On bigger ships, high-speed diesel engines are often used for powering electric generators.[165] The highest power output of high-speed diesel engines is approximately 5 MW.[166]

- Medium-speed diesel engines

Medium-speed engines are used in large electrical generators, railway diesel locomotives, ship propulsion and mechanical drive applications such as large compressors or pumps. Medium speed diesel engines operate on either diesel fuel or heavy fuel oil by direct injection in the same manner as low-speed engines. Usually, they are four-stroke engines with trunk pistons;[167] a notable exception being the EMD 567, 645, and 710 engines, which are all two-stroke.[168]

The power output of medium-speed diesel engines can be as high as 21,870 kW,[169] with the effective efficiency being around 47-48% (1982).[170] Most larger medium-speed engines are started with compressed air direct on pistons, using an air distributor, as opposed to a pneumatic starting motor acting on the flywheel, which tends to be used for smaller engines.[171]

Medium-speed engines intended for marine applications are usually used to power (ro-ro) ferries, passenger ships or small freight ships. Using medium-speed engines reduces the cost of smaller ships and increases their transport capacity. In addition to that, a single ship can use two smaller engines instead of one big engine, which increases the ship's safety.[167]

- Low-speed diesel engines

Low-speed diesel engines are usually very large in size and mostly used to power ships. There are two different types of low-speed engines that are commonly used: Two-stroke engines with a crosshead, and four-stroke engines with a regular trunk-piston. Two-stroke engines have a limited rotational frequency and their charge exchange is more difficult, which means that they are usually bigger than four-stroke engines and used to directly power a ship's propeller.

Four-stroke engines on ships are usually used to power an electric generator. An electric motor powers the propeller.[162] Both types are usually very undersquare, meaning the bore is smaller than the stroke.[172] Low-speed diesel engines (as used in ships and other applications where overall engine weight is relatively unimportant) often have an effective efficiency of up to 55%.[1] Like medium-speed engines, low-speed engines are started with compressed air, and they use heavy oil as their primary fuel.[171]

Combustion cycle

[edit]

Four-stroke engines use the combustion cycle described earlier. Most smaller diesels, for vehicular use, for instance, typically use the four-stroke cycle. This is due to several factors, such as the two-stroke design's narrow powerband which is not particularly suitable for automotive use and the necessity for complicated and expensive built-in lubrication systems and scavenging measures.[173] The cost effectiveness (and proportion of added weight) of these technologies has less of an impact on larger, more expensive engines, while engines intended for shipping or stationary use can be run at a single speed for long periods.[173]

Two-stroke engines use a combustion cycle which is completed in two strokes instead of four strokes. Filling the cylinder with air and compressing it takes place in one stroke, and the power and exhaust strokes are combined. The compression in a two-stroke diesel engine is similar to the compression that takes place in a four-stroke diesel engine: As the piston passes through bottom centre and starts upward, compression commences, culminating in fuel injection and ignition. Instead of a full set of valves, two-stroke diesel engines have simple intake ports, and exhaust ports (or exhaust valves). When the piston approaches bottom dead centre, both the intake and the exhaust ports are "open", which means that there is atmospheric pressure inside the cylinder. Therefore, some sort of pump is required to blow the air into the cylinder and the combustion gasses into the exhaust. This process is called scavenging. The pressure required is approximately 10-30 kPa.[174]

Due to the lack of discrete exhaust and intake strokes, all two-stroke diesel engines use a scavenge blower or some form of compressor to charge the cylinders with air and assist in scavenging.[174] Roots-type superchargers were used for ship engines until the mid-1950s, however since 1955 they have been widely replaced by turbochargers.[175] Usually, a two-stroke ship diesel engine has a single-stage turbocharger with a turbine that has an axial inflow and a radial outflow.[176]

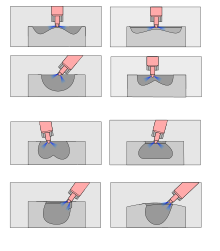

Scavenging in two-stroke engines

[edit]In general, there are three types of scavenging possible:

- Uniflow scavenging

- Crossflow scavenging

- Reverse flow scavenging

Crossflow scavenging is incomplete and limits the stroke, yet some manufacturers used it.[177] Reverse flow scavenging is a very simple way of scavenging, and it was popular amongst manufacturers until the early 1980s. Uniflow scavenging is more complicated to make but allows the highest fuel efficiency; since the early 1980s, manufacturers such as MAN and Sulzer have switched to this system.[125] It is standard for modern marine two-stroke diesel engines.[2]

Fuel used

[edit]So-called dual-fuel diesel engines or gas diesel engines burn two different types of fuel simultaneously, for instance, a gaseous fuel and diesel engine fuel. The diesel engine fuel auto-ignites due to compression ignition, and then ignites the gaseous fuel. Such engines do not require any type of spark ignition and operate similar to regular diesel engines.[178][179]

Fuel injection

[edit]The fuel is injected at high pressure into either the combustion chamber, "swirl chamber" or "pre-chamber,"[143] unlike petrol engines where the fuel is often added in the inlet manifold or carburetor. Engines where the fuel is injected into the main combustion chamber are called direct injection (DI) engines, while those which use a swirl chamber or pre-chamber are called indirect injection (IDI) engines.[180]

Direct injection

[edit]

Most direct injection diesel engines have a combustion cup in the top of the piston where the fuel is sprayed. Many different methods of injection can be used. Usually, an engine with helix-controlled mechanic direct injection has either an inline or a distributor injection pump.[160] For each engine cylinder, the corresponding plunger in the fuel pump measures out the correct amount of fuel and determines the timing of each injection. These engines use injectors that are very precise spring-loaded valves that open and close at a specific fuel pressure. Separate high-pressure fuel lines connect the fuel pump with each cylinder. Fuel volume for each single combustion is controlled by a slanted groove in the plunger which rotates only a few degrees releasing the pressure and is controlled by a mechanical governor, consisting of weights rotating at engine speed constrained by springs and a lever. The injectors are held open by the fuel pressure. On high-speed engines the plunger pumps are together in one unit.[181] The length of fuel lines from the pump to each injector is normally the same for each cylinder in order to obtain the same pressure delay. Direct injected diesel engines usually use orifice-type fuel injectors.[182]

Electronic control of the fuel injection transformed the direct injection engine by allowing much greater control over the combustion.[183]

- Common rail

Common rail (CR) direct injection systems do not have the fuel metering, pressure-raising and delivery functions in a single unit, as in the case of a Bosch distributor-type pump, for example. A high-pressure pump supplies the CR. The requirements of each cylinder injector are supplied from this common high pressure reservoir of fuel. An Electronic Diesel Control (EDC) controls both rail pressure and injections depending on engine operating conditions. The injectors of older CR systems have solenoid-driven plungers for lifting the injection needle, whilst newer CR injectors use plungers driven by piezoelectric actuators that have less moving mass and therefore allow even more injections in a very short period of time.[184] Early common rail system were controlled by mechanical means.

The injection pressure of modern CR systems ranges from 140 MPa to 270 MPa.[185]

Indirect injection

[edit]

An indirect diesel injection system (IDI) engine delivers fuel into a small chamber called a swirl chamber, precombustion chamber, pre chamber or ante-chamber, which is connected to the cylinder by a narrow air passage. Generally the goal of the pre chamber is to create increased turbulence for better air / fuel mixing. This system also allows for a smoother, quieter running engine, and because fuel mixing is assisted by turbulence, injector pressures can be lower. Most IDI systems use a single orifice injector. The pre-chamber has the disadvantage of lowering efficiency due to increased heat loss to the engine's cooling system, restricting the combustion burn, thus reducing the efficiency by 5–10%. IDI engines are also more difficult to start and usually require the use of glow plugs. IDI engines may be cheaper to build but generally require a higher compression ratio than the DI counterpart. IDI also makes it easier to produce smooth, quieter running engines with a simple mechanical injection system since exact injection timing is not as critical. Most modern automotive engines are DI which have the benefits of greater efficiency and easier starting; however, IDI engines can still be found in the many ATV and small diesel applications.[186] Indirect injected diesel engines use pintle-type fuel injectors.[182]

Air-blast injection

[edit]

Early diesel engines injected fuel with the assistance of compressed air, which atomised the fuel and forced it into the engine through a nozzle (a similar principle to an aerosol spray). The nozzle opening was closed by a pin valve actuated by the camshaft. Although the engine was also required to drive an air compressor used for air-blast injection, the efficiency was nonetheless better than other combustion engines of the time.[52] However the system was heavy and it was slow to react to changing torque demands, making it unsuitable for road vehicles.[187]

Unit injectors

[edit]A unit injector system, also known as "Pumpe-Düse" (pump-nozzle in German) combines the injector and fuel pump into a single component, which is positioned above each cylinder. This eliminates the high-pressure fuel lines and achieves a more consistent injection. Under full load, the injection pressure can reach up to 220 MPa.[188] Unit injectors are operated by a cam and the quantity of fuel injected is controlled either mechanically (by a rack or lever) or electronically.

Due to increased performance requirements, unit injectors have been largely replaced by common rail injection systems.[164]

Diesel engine particularities

[edit]Mass

[edit]The average diesel engine has a poorer power-to-mass ratio than an equivalent petrol engine. The lower engine speeds (RPM) of typical diesel engines results in a lower power output.[189] Also, the mass of a diesel engine is typically higher, since the higher operating pressure inside the combustion chamber increases the internal forces, which requires stronger (and therefore heavier) parts to withstand these forces.[190]

Noise ("diesel clatter")

[edit]The distinctive noise of a diesel engine, particularly at idling speeds, is sometimes called "diesel clatter". This noise is largely caused by the sudden ignition of the diesel fuel when injected into the combustion chamber, which causes a pressure wave that sounds like knocking.

Engine designers can reduce diesel clatter through: indirect injection; pilot or pre-injection;[191] injection timing; injection rate; compression ratio; turbo boost; and exhaust gas recirculation (EGR).[192] Common rail diesel injection systems permit multiple injection events as an aid to noise reduction. Through measures such as these, diesel clatter noise is greatly reduced in modern engines. Diesel fuels with a higher cetane rating are more likely to ignite and hence reduce diesel clatter.[193]

Cold weather starting

[edit]In warmer climates, diesel engines do not require any starting aid (aside from the starter motor). However, many diesel engines include some form of preheating for the combustion chamber, to assist starting in cold conditions. Engines with a displacement of less than 1 litre per cylinder usually have glowplugs, whilst larger heavy-duty engines have flame-start systems.[194] The minimum starting temperature that allows starting without pre-heating is 40 °C (104 °F) for precombustion chamber engines, 20 °C (68 °F) for swirl chamber engines, and 0 °C (32 °F) for direct injected engines.

In the past, a wider variety of cold-start methods were used. Some engines, such as Detroit Diesel engines used[when?] a system to introduce small amounts of ether into the inlet manifold to start combustion.[195] Instead of glowplugs, some diesel engines are equipped with starting aid systems that change valve timing. The simplest way this can be done is with a decompression lever. Activating the decompression lever locks the outlet valves in a slight down position, resulting in the engine not having any compression and thus allowing for turning the crankshaft over with significantly less resistance. When the crankshaft reaches a higher speed, flipping the decompression lever back into its normal position will abruptly re-activate the outlet valves, resulting in compression − the flywheel's mass moment of inertia then starts the engine.[196] Other diesel engines, such as the precombustion chamber engine XII Jv 170/240 made by Ganz & Co., have a valve timing changing system that is operated by adjusting the inlet valve camshaft, moving it into a slight "late" position. This will make the inlet valves open with a delay, forcing the inlet air to heat up when entering the combustion chamber.[197]

Supercharging & turbocharging

[edit]

Forced induction, especially turbocharging is commonly used on diesel engines because it greatly increases efficiency and torque output.[198] Diesel engines are well suited for forced induction setups due to their operating principle which is characterised by wide ignition limits[143] and the absence of fuel during the compression stroke. Therefore, knocking, pre-ignition or detonation cannot occur, and a lean mixture caused by excess supercharging air inside the combustion chamber does not negatively affect combustion.[199]

Major manufacturers

[edit]- MTU

- MAN

- Wartsila

- Rolls-Royce Power Systems

- Siemens

- Kolomna KDZ TMH BMZ and UDMZ

- General Electric GE Transportation

- Volvo Penta

- Sulzer (manufacturer)

- Doosan Doosan infracore, Doosan Marine

- YaMZ VAZ, KMZ - RD Nevsky, STM GAZ VMZ VMZ

- Mitsubishi, Mitsui Mazda IHI Kawasaki Honda Suzuki Subaru Isuzu Nissan plus others

- Caterpillar and Cummins

- AO Zvezda and Zvezda Energetika

- Bergen Engines MaK Deutz AG MWM BMW VW, MAPNA BHEL DESA Steyr Motors GmbH Iran Khodro Diesel Isotta Fraschini, EMD Fairbanks Morse, Shanxi Henan Diesel SDM

Fuel and fluid characteristics

[edit]Diesel engines can combust a huge variety of fuels, including several fuel oils that have advantages over fuels such as petrol. These advantages include:

- Low fuel costs, as fuel oils are relatively cheap

- Good lubrication properties

- High energy density

- Low risk of catching fire, as they do not form a flammable vapour

- Biodiesel is an easily synthesised, non-petroleum-based fuel (through transesterification) which can run directly in many diesel engines, while gasoline engines either need adaptation to run synthetic fuels or else use them as an additive to gasoline (e.g., ethanol added to gasohol).

In diesel engines, a mechanical injector system atomizes the fuel directly into the combustion chamber (as opposed to a Venturi jet in a carburetor, or a fuel injector in a manifold injection system atomizing fuel into the intake manifold or intake runners as in a petrol engine). Because only air is inducted into the cylinder in a diesel engine, the compression ratio can be much higher as there is no risk of pre-ignition provided the injection process is accurately timed.[199] This means that cylinder temperatures are much higher in a diesel engine than a petrol engine, allowing less volatile fuels to be used.

Therefore, diesel engines can operate on a huge variety of different fuels. In general, fuel for diesel engines should have a proper viscosity, so that the injection pump can pump the fuel to the injection nozzles without causing damage to itself or corrosion of the fuel line. At injection, the fuel should form a good fuel spray, and it should not have a coking effect upon the injection nozzles. To ensure proper engine starting and smooth operation, the fuel should be willing to ignite and hence not cause a high ignition delay, (this means that the fuel should have a high cetane number). Diesel fuel should also have a high lower heating value.[200]

Inline mechanical injector pumps generally tolerate poor-quality or bio-fuels better than distributor-type pumps. Also, indirect injection engines generally run more satisfactorily on fuels with a high ignition delay (for instance, petrol) than direct injection engines.[201] This is partly because an indirect injection engine has a much greater 'swirl' effect, improving vaporisation and combustion of fuel, and because (in the case of vegetable oil-type fuels) lipid depositions can condense on the cylinder walls of a direct-injection engine if combustion temperatures are too low (such as starting the engine from cold). Direct-injected engines with an MAN centre sphere combustion chamber rely on fuel condensing on the combustion chamber walls. The fuel starts vaporising only after ignition sets in, and it burns relatively smoothly. Therefore, such engines also tolerate fuels with poor ignition delay characteristics, and, in general, they can operate on petrol rated 86 RON.[202]

Fuel types

[edit]In his 1893 work Theory and Construction of a Rational Heat Motor, Rudolf Diesel considers using coal dust as fuel for the diesel engine. However, Diesel just considered using coal dust (as well as liquid fuels and gas); his actual engine was designed to operate on petroleum, which was soon replaced with regular petrol and kerosene for further testing purposes, as petroleum proved to be too viscous.[203] In addition to kerosene and petrol, Diesel's engine could also operate on ligroin.[204]

Before diesel engine fuel was standardised, fuels such as petrol, kerosene, gas oil, vegetable oil and mineral oil, as well as mixtures of these fuels, were used.[205] Typical fuels specifically intended to be used for diesel engines were petroleum distillates and coal-tar distillates such as the following; these fuels have specific lower heating values of:

- Diesel oil: 10,200 kcal·kg−1 (42.7 MJ·kg−1) up to 10,250 kcal·kg−1 (42.9 MJ·kg−1)

- Heating oil: 10,000 kcal·kg−1 (41.8 MJ·kg−1) up to 10,200 kcal·kg−1 (42.7 MJ·kg−1)

- Coal-tar creosote: 9,150 kcal·kg−1 (38.3 MJ·kg−1) up to 9,250 kcal·kg−1 (38.7 MJ·kg−1)

- Kerosene: up to 10,400 kcal·kg−1 (43.5 MJ·kg−1)

Source:[206]

The first diesel fuel standards were the DIN 51601, VTL 9140-001, and NATO F 54, which appeared after World War II.[205] The modern European EN 590 diesel fuel standard was established in May 1993; the modern version of the NATO F 54 standard is mostly identical with it. The DIN 51628 biodiesel standard was rendered obsolete by the 2009 version of the EN 590; FAME biodiesel conforms to the EN 14214 standard. Watercraft diesel engines usually operate on diesel engine fuel that conforms to the ISO 8217 standard (Bunker C). Also, some diesel engines can operate on gasses (such as LNG).[207]

Modern diesel fuel properties

[edit]| EN 590 (as of 2009) | EN 14214 (as of 2010) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ignition performance | ≥ 51 CN | ≥ 51 CN |

| Density at 15 °C | 820...845 kg·m−3 | 860...900 kg·m−3 |

| Sulfur content | ≤10 mg·kg−1 | ≤10 mg·kg−1 |

| Water content | ≤200 mg·kg−1 | ≤500 mg·kg−1 |

| Lubricity | 460 μm | 460 μm |

| Viscosity at 40 °C | 2.0...4.5 mm2·s−1 | 3.5...5.0 mm2·s−1 |

| FAME content | ≤7.0% | ≥96.5% |

| Molar H/C ratio | – | 1.69 |

| Lower heating value | – | 37.1 MJ·kg−1 |

Gelling

[edit]DIN 51601 diesel fuel was prone to waxing or gelling in cold weather; both are terms for the solidification of diesel oil into a partially crystalline state. The crystals build up in the fuel system (especially in fuel filters), eventually starving the engine of fuel and causing it to stop running.[209] Low-output electric heaters in fuel tanks and around fuel lines were used to solve this problem. Also, most engines have a spill return system, by which any excess fuel from the injector pump and injectors is returned to the fuel tank. Once the engine has warmed, returning warm fuel prevents waxing in the tank. Before direct injection diesel engines, some manufacturers, such as BMW, recommended mixing up to 30% petrol in with the diesel by fuelling diesel cars with petrol to prevent the fuel from gelling when the temperatures dropped below −15 °C.[210]

Safety

[edit]Fuel flammability

[edit]Diesel fuel is less flammable than petrol, because its flash point is 55 °C,[209][211] leading to a lower risk of fire caused by fuel in a vehicle equipped with a diesel engine.

Diesel fuel can create an explosive air/vapour mix under the right conditions. However, compared with petrol, it is less prone due to its lower vapour pressure, which is an indication of evaporation rate. The Material Safety Data Sheet[212] for ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel indicates a vapour explosion hazard for diesel fuel indoors, outdoors, or in sewers.

Cancer

[edit]Diesel exhaust has been classified as an IARC Group 1 carcinogen. It causes lung cancer and is associated with an increased risk for bladder cancer.[213]

Engine runaway (uncontrollable overspeeding)

[edit]Applications

[edit]The characteristics of diesel have different advantages for different applications.

Passenger cars

[edit]Diesel engines have long been popular in bigger cars and have been used in smaller cars such as superminis in Europe since the 1980s. They were popular in larger cars earlier, as the weight and cost penalties were less noticeable.[214] Smooth operation as well as high low-end torque are deemed important for passenger cars and small commercial vehicles. The introduction of electronically controlled fuel injection significantly improved the smooth torque generation, and starting in the early 1990s, car manufacturers began offering their high-end luxury vehicles with diesel engines. Passenger car diesel engines usually have between three and twelve cylinders, and a displacement ranging from 0.8 to 6.0 litres. Modern powerplants are usually turbocharged and have direct injection.[163]

Diesel engines do not suffer from intake-air throttling, resulting in very low fuel consumption especially at low partial load[215] (for instance: driving at city speeds). One fifth of all passenger cars worldwide have diesel engines, with many of them being in Europe, where approximately 47% of all passenger cars are diesel-powered.[216] Daimler-Benz in conjunction with Robert Bosch GmbH produced diesel-powered passenger cars starting in 1936.[81] The popularity of diesel-powered passenger cars in markets such as India, South Korea and Japan is increasing (as of 2018).[217]

Commercial vehicles and lorries

[edit]Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

In 1893, Rudolf Diesel suggested that the diesel engine could possibly power "wagons" (lorries).[219] The first lorries with diesel engines were brought to market in 1924.[81]

Modern diesel engines for lorries have to be both extremely reliable and very fuel efficient. Common-rail direct injection, turbocharging and four valves per cylinder are standard. Displacements range from 4.5 to 15.5 litres, with power-to-mass ratios of 2.5–3.5 kg·kW−1 for heavy duty and 2.0–3.0 kg·kW−1 for medium duty engines. V6 and V8 engines used to be common, due to the relatively low engine mass the V configuration provides. Recently, the V configuration has been abandoned in favour of straight engines. These engines are usually straight-6 for heavy and medium duties and straight-4 for medium duty. Their undersquare design causes lower overall piston speeds which results in increased lifespan of up to 1,200,000 kilometres (750,000 mi).[220] Compared with 1970s diesel engines, the expected lifespan of modern lorry diesel engines has more than doubled.[218]

Railroad rolling stock

[edit]Diesel engines for locomotives are built for continuous operation between refuelings and may need to be designed to use poor quality fuel in some circumstances.[221] Some locomotives use two-stroke diesel engines.[222] Diesel engines have replaced steam engines on all non-electrified railroads in the world. The first diesel locomotives appeared in 1913,[81] and diesel multiple units soon after. Nearly all modern diesel locomotives are more correctly known as diesel–electric locomotives because they use an electric transmission: the diesel engine drives an electric generator which powers electric traction motors.[223] While electric locomotives have replaced the diesel locomotive for passenger services in many areas diesel traction is widely used for cargo-hauling freight trains and on tracks where electrification is not economically viable.

In the 1940s, road vehicle diesel engines with power outputs of 150–200 metric horsepower (110–150 kW; 150–200 hp) were considered reasonable for DMUs. Commonly, regular truck powerplants were used. The height of these engines had to be less than 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) to allow underfloor installation. Usually, the engine was mated with a pneumatically operated mechanical gearbox, due to the low size, mass, and production costs of this design. Some DMUs used hydraulic torque converters instead. Diesel–electric transmission was not suitable for such small engines.[224] In the 1930s, the Deutsche Reichsbahn standardised its first DMU engine. It was a 30.3 litres (1,850 cu in), 12-cylinder boxer unit, producing 275 metric horsepower (202 kW; 271 hp). Several German manufacturers produced engines according to this standard.[225]

Watercraft

[edit]

The requirements for marine diesel engines vary, depending on the application. For military use and medium-size boats, medium-speed four-stroke diesel engines are most suitable. These engines usually have up to 24 cylinders and come with power outputs in the one-digit Megawatt region.[221] Small boats may use lorry diesel engines. Large ships use extremely efficient, low-speed two-stroke diesel engines. They can reach efficiencies of up to 55%. Unlike most regular diesel engines, two-stroke watercraft engines use highly viscous fuel oil.[1] Submarines are usually diesel–electric.[223]

The first diesel engines for ships were made by A. B. Diesels Motorer Stockholm in 1903. These engines were three-cylinder units of 120 PS (88 kW) and four-cylinder units of 180 PS (132 kW) and used for Russian ships. In World War I, especially submarine diesel engine development advanced quickly. By the end of the War, double acting piston two-stroke engines with up to 12,200 PS (9 MW) had been made for marine use.[226]

Aviation

[edit]Early

[edit]Diesel engines had been used in aircraft before World War II, for instance, in the rigid airship LZ 129 Hindenburg, which was powered by four Daimler-Benz DB 602 diesel engines,[227] or in several Junkers aircraft, which had Jumo 205 engines installed.[101]

In 1929, in the United States, the Packard Motor Company developed America's first aircraft diesel engine, the Packard DR-980—an air-cooled, 9-cylinder radial engine. They installed it in various aircraft of the era—some of which were used in record-breaking distance or endurance flights,[228][229][230][231] and in the first successful demonstration of ground-to-air radiophone communications (voice radio having been previously unintelligible in aircraft equipped with spark-ignition engines, due to electromagnetic interference).[229][230] Additional advantages cited, at the time, included a lower risk of post-crash fire, and superior performance at high altitudes.[229]

On March 6, 1930, the engine received an Approved Type Certificate—first ever for an aircraft diesel engine—from the U.S. Department of Commerce.[232] However, noxious exhaust fumes, cold-start and vibration problems, engine structural failures, the death of its developer, and the industrial economic contraction of the Great Depression, combined to kill the program.[229]

Modern

[edit]From then, until the late 1970s, there had not been many applications of the diesel engine in aircraft. In 1978, Piper Cherokee co-designer Karl H. Bergey argued that "the likelihood of a general aviation diesel in the near future is remote."[233]

However, with the 1970s energy crisis and environmental movement, and resulting pressures for greater fuel economy, reduced carbon and lead in the atmosphere, and other issues, there was a resurgence of interest in diesel engines for aircraft. High-compression piston aircraft engines that run on aviation gasoline ("avgas") generally require the addition of toxic Tetraethyl lead to avgas, to avoid engine pre-ignition and detonation; but diesel engines do not require leaded fuel. Also, biodiesel can, theoretically, provide a net reduction in atmospheric carbon compared to avgas. For these reasons, the general aviation community has begun to fear the possible banning or discontinuance of leaded avgas.[8][234][235][236]

Additionally, avgas is a specialty fuel in very low (and declining) demand, compared to other fuels, and its makers are susceptible to costly aviation-crash lawsuits, reducing refiners' interest in producing it. Outside the United States, avgas has already become increasingly difficult to find at airports (and generally), than less-expensive, diesel-compatible fuels like Jet-A and other jet fuels.[8][234][235][236]

By the late 1990s / early 2000s, diesel engines were beginning to appear in light aircraft. Most notably, Frank Thielert and his Austrian engine enterprise, began developing diesel engines to replace the 100 horsepower (75 kW) - 350 horsepower (260 kW) gasoline/piston engines in common light aircraft use.[237] First successful application of the Theilerts to production aircraft was in the Diamond DA42 Twin Star light twin, which exhibited exceptional fuel efficiency surpassing anything in its class,[8][9][238] and its single-seat predecessor, the Diamond DA40 Diamond Star.[8][9][237]

In subsequent years, several other companies have developed aircraft diesel engines, or have begun to[237]—most notably Continental Aerospace Technologies which, by 2018, was reporting it had sold over 5,000 such engines worldwide.[8][9][239]

The United States' Federal Aviation Administration has reported that "by 2007, various jet-fueled piston aircraft had logged well over 600,000 hours of service".[237] In early 2019, AOPA reported that a diesel engine model for general aviation aircraft is "approaching the finish line."[240] By late 2022, Continental was reporting that its "Jet-A" fueled engines had exceeded "2,000... in operation today," with over "9 million hours," and were being "specified by major OEMs" for Cessna, Piper, Diamond, Mooney, Tecnam, Glasair and Robin aircraft.[239]

In recent years (2016), diesel engines have also found use in unmanned aircraft (UAV), due to their reliability, durability, and low fuel consumption.[241][242][243]

Non-road diesel engines

[edit]

Non-road diesel engines are commonly used for construction equipment and agricultural machinery. Fuel efficiency, reliability and ease of maintenance are very important for such engines, whilst high power output and quiet operation are negligible. Therefore, mechanically controlled fuel injection and air-cooling are still very common. The common power outputs of non-road diesel engines vary a lot, with the smallest units starting at 3 kW, and the most powerful engines being heavy duty lorry engines.[221]

Stationary diesel engines

[edit]

Stationary diesel engines are commonly used for electricity generation, but also for powering refrigerator compressors, or other types of compressors or pumps. Usually, these engines either run continuously with partial load, or intermittently with full load. Stationary diesel engines powering electric generators that put out an alternating current, usually operate with alternating load, but fixed rotational frequency. This is due to the mains' fixed frequency of either 50 Hz (Europe), or 60 Hz (United States). The engine's crankshaft rotational frequency is chosen so that the mains' frequency is a multiple of it. For practical reasons, this results in crankshaft rotational frequencies of either 25 Hz (1500 per minute) or 30 Hz (1800 per minute).[244]

Low heat rejection engines

[edit]A special class of prototype internal combustion piston engines has been developed over several decades with the goal of improving efficiency by reducing heat loss.[245] These engines are variously called adiabatic engines; due to better approximation of adiabatic expansion; low heat rejection engines, or high temperature engines.[246] They are generally piston engines with combustion chamber parts lined with ceramic thermal barrier coatings.[247] Some make use of pistons and other parts made of titanium which has a low thermal conductivity[248] and density. Some designs are able to eliminate the use of a cooling system and associated parasitic losses altogether.[249] Developing lubricants able to withstand the higher temperatures involved has been a major barrier to commercialization.[250]

Future developments

[edit]In mid-2010s literature, main development goals for future diesel engines are described as improvements of exhaust emissions, reduction of fuel consumption, and increase of lifespan (2014).[251][163] It is said that the diesel engine, especially the diesel engine for commercial vehicles, will remain the most important vehicle powerplant until the mid-2030s. Editors assume that the complexity of the diesel engine will increase further (2014).[252] Some editors expect a future convergency of diesel and Otto engines' operating principles due to Otto engine development steps made towards homogeneous charge compression ignition (2017).[253]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Konrad Reif (ed.): Dieselmotor-Management im Überblick. 2nd edition. Springer, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-658-06554-6. p. 13

- ^ a b Karl-Heinrich Grote, Beate Bender, Dietmar Göhlich (ed.): Dubbel – Taschenbuch für den Maschinenbau, 25th edition, Springer, Heidelberg 2018, ISBN 978-3-662-54804-2, 1205 pp. (P93)

- ^ Ramey, Jay (April 13, 2021), "10 Diesel Cars That Time Forgot", Autoweek, Hearst Autos, Inc., archived from the original on December 6, 2022

- ^ "Critical evaluation of the European diesel car boom - global comparison, environmental effects and various national strategies," 2013, Environmental Sciences Europe, volume 25, Article number: 15, retrieved December 5, 2022

- ^ Konrad Reif (ed.): Dieselmotor-Management – Systeme Komponenten und Regelung, 5th edition, Springer, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-8348-1715-0, p. 286

- ^ Huffman, John Pearley: "Every New 2021 Diesel for Sale in the U.S. Today," March 6, 2021, Car and Driver, retrieved December 5, 2022

- ^ Gorzelany, Jim: "The Best 15 Best Diesel Vehicles of 2021," April 23, 2021, U.S. News, retrieved December 5, 2022

- ^ a b c d e f "Inside the Diesel Revolution," August 1, 2018, Flying, retrieved December 5, 2022

- ^ a b c d O'Connor, Kate: "Diamond Rolls Out 500th DA40 NG," December 30, 2020 Updated: December 31, 2020, Avweb, retrieved December 5, 2022

- ^ a b c Rudolf Diesel: Die Entstehung des Dieselmotors, Springer, Berlin 1913, ISBN 978-3-642-64940-0. p. 22

- ^ a b Rudolf Diesel: Die Entstehung des Dieselmotors, Springer, Berlin 1913, ISBN 978-3-642-64940-0. p. 64

- ^ Rudolf Diesel: Die Entstehung des Dieselmotors, Springer, Berlin 1913, ISBN 978-3-642-64940-0. p. 75

- ^ Rudolf Diesel: Die Entstehung des Dieselmotors, Springer, Berlin 1913, ISBN 978-3-642-64940-0. p. 78

- ^ a b Rudolf Diesel: Die Entstehung des Dieselmotors, Springer, Berlin 1913, ISBN 978-3-642-64940-0. p. 1

- ^ Ogata, Masanori; Shimotsuma, Yorikazu (October 20–21, 2002). "Origin of Diesel Engine is in Fire Piston of Mountainous People Lived in Southeast Asia". First International Conference on Business and technology Transfer. Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers. Archived from the original on May 23, 2007. Retrieved May 28, 2007.

- ^ Sittauer, Hans L. (1990), Nicolaus August Otto Rudolf Diesel, Biographien hervorragender Naturwissenschaftler, Techniker und Mediziner (in German), 32 (4th ed.), Leipzig, DDR: Springer (BSB Teubner), ISBN 978-3-322-00762-9. p. 70

- ^ Sittauer, Hans L. (1990), Nicolaus August Otto Rudolf Diesel, Biographien hervorragender Naturwissenschaftler, Techniker und Mediziner (in German), 32 (4th ed.), Leipzig, DDR: Springer (BSB Teubner), ISBN 978-3-322-00762-9. p. 71

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 398

- ^ a b Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 399

- ^ US patent (granted in 1895) #542846 pdfpiw.uspto.gov Archived April 26, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 402

- ^ "Patent Images". Pdfpiw.uspto.gov. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Diesel, Rudolf (October 28, 1897). Diesel's Rational Heat Motor: A Lecture. Progressive Age Publishing Company. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

diesel rational heat motor.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Method Of and Apparatus For Converting Heat Into Work, United States Patent No. 542,846, Filed Aug 26, 1892, Issued July 16, 1895, Inventor Rudolf Diesel of Berlin Germany

- ^ ES 16654 "Perfeccionamientos en los motores de combustión interior."

- ^ Internal-Combustion Engine, U.S. Patent number 608845, Filed Jul 15 1895, Issued August 9, 1898, Inventor Rudolf Diesel, Assigned to the Diesel Motor Company of America (New York)

- ^ a b Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 486

- ^ a b Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 400

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 412

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 487

- ^ a b Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 414

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 518

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 395

- ^ Sittauer, Hans L. (1990), Nicolaus August Otto Rudolf Diesel, Biographien hervorragender Naturwissenschaftler, Techniker und Mediziner (in German), 32 (4th ed.), Leipzig, DDR: Springer (BSB Teubner), ISBN 978-3-322-00762-9. p. 74

- ^ a b Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 559

- ^ a b Rudolf Diesel: Die Entstehung des Dieselmotors, Springer, Berlin 1913, ISBN 978-3-642-64940-0. p. 17

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 444

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 415

- ^ Moon, John F. (1974). Rudolf Diesel and the Diesel Engine. London: Priory Press. ISBN 978-0-85078-130-4.

- ^ a b Helmut Tschöke, Klaus Mollenhauer, Rudolf Maier (ed.): Handbuch Dieselmotoren, 8th edition, Springer, Wiesbaden 2018, ISBN 978-3-658-07696-2, p. 6

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 462

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 463

- ^ Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 464

- ^ a b Friedrich Sass: Geschichte des deutschen Verbrennungsmotorenbaus von 1860 bis 1918, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 1962, ISBN 978-3-662-11843-6. p. 466