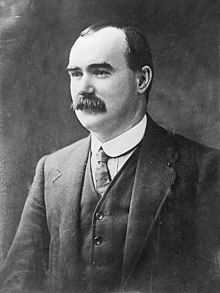

James Connolly

James Connolly | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 5 June 1868 |

| Died | 12 May 1916 (aged 47) Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin, Ireland |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Organization | Industrial Workers of the World (1905–1910) Irish Transport and General Workers Union (1910−1916) |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 7, including Nora and Roddy |

| Military service | |

| Buried | Arbour Hill Prison, Dublin |

| Service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Commandant General |

| Unit |

|

| Battles / wars | Easter Rising |

James Connolly (Irish: Séamas Ó Conghaile;[1] 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was a Scottish-born Irish republican, socialist, and trade union leader, executed for his part in the 1916 Easter Rising against British rule in Ireland. He remains an important figure both for the Irish labour movement and for Irish republicanism.

He became an active socialist in Scotland, where he had been born in 1868 to Irish parents. On moving to Ireland in 1896, he established the country's first socialist party, the Irish Socialist Republican Party. It called for an Ireland independent not only of Britain's Crown and Parliament, but also of British "capitalists, landlords and financiers".

From 1905 to 1910, he was a full-time organiser in the United States for the Industrial Workers of the World, choosing its syndicalism over the doctrinaire Marxism of Daniel DeLeon's Socialist Labor Party of America, to which he had been initially drawn. Returning to Ireland, he deputised for James Larkin in organising for the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, first in Belfast and then in Dublin.

In Belfast, he was frustrated in his efforts to draw Protestant workers into an all-Ireland labour and socialist movement but, in the wake of the industrial unrest of 1913, acquired in Dublin what he saw as a new means of striking toward the goal of a Workers' Republic. At the beginning of 1916, he committed the union's militia, the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), to the plans of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and the Irish Volunteers, for war-time insurrection.

Alongside Patrick Pearse, Connolly commanded the insurrection in Easter of that year from rebel garrison holding Dublin's General Post Office. He was wounded in the fighting and, following the rebel surrender at the end of Easter week, was executed along with the six other signatories to the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

Early life

[edit]Connolly was born in the Cowgate or "Little Ireland" district of Edinburgh in 1868, the third son of Mary McGinn and John Connolly, a labourer,[2]: 28 both Irish immigrants his mother from Ballymena, County Antrim and his father from County Monaghan. Throughout his life he was to speak with a Scottish accent.[3]: 636

Relying on his biographer Desmond Greaves, most accounts of his life suggest that it was with the British Army that Connolly first came to Ireland. Greaves reports that Connolly reminisced about being on military guard duty in Cork Harbour on the night in December 1882 when Maolra Seoighe was hanged for the Maamtrasna massacre (the killing of a landlord and his family).[4]: 26 This might suggest that, having been listed in the census of the previous year as a 12-year old baker's apprentice,[3]: 7 Connolly had falsified his age and name to enlist in the 1st Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment (recruited heavily from the Irish in Britain). If so, it is possible the Connolly also saw service in County Meath during the Land War and in Belfast during the town's deadly sectarian riots in 1886.[5] But absent documentation of his military service, this is a matter of speculation.[6] According to Nora, her father left the army in February 1889 and returned to Scotland.[7]

In Dublin, Connolly had met Lillie Reynolds, and in the New Year, 1890, she followed him to Scotland where, with special dispensation (Reynolds was Protestant) they married in a Catholic church.[8]: 15

Socialist republican

[edit]After Ireland is free, says the patriot who won't touch Socialism, we will protect all classes, and if you won't pay your rent you will be evicted same as now. But the evicting party, under command of the sheriff, will wear green uniforms and the Harp without the Crown, and the warrant turning you out on the roadside will be stamped with the arms of the Irish Republic.

Scottish Socialist Federation

[edit]Again following in the example of his brother John, in 1890 Connolly joined the Scottish Socialist Federation, succeeding his brother as its secretary in 1893. Largely a propaganda organisation, the Federation supported Keir Hardie and his Independent Labour Party in the campaign for labour representation in Parliament.[9]

Within the SSF, Connolly was greatly influenced by John Leslie, 12 years his senior, but like him born to poor Irish immigrants. While Leslie did not envisage Ireland breaking the English connection before the advent of a socialist Britain, he was to encourage Connolly in the creation of a separate socialist party in Ireland.[10]

In 1896, after the birth of his third daughter, and having lost, while standing for election to the city-council, his municipal carter's job, and then failed as a cobbler, Connolly considered a future for his family in Chile. But thanks to an appeal by John Leslie, he had the offer of employment in Dublin as a full-time secretary for the Dublin Socialist Club, at £1 per week.[3]: 47–48

Irish Socialist Republican Party

[edit]In Dublin, where he first became a navvy and then a proof reader, Connolly soon split the Socialist Club, forming in its stead the Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP).[11] In what was then, if briefly, the "literary centre of advanced nationalism",[12]: 44 Alice Milligan's Belfast monthly, The Shan Van Vocht, he published a first statement of the party credo, "Socialism and Nationalism"", This suggested that, even if a step toward formal independence, the legislature that the Irish Parliamentary Party wished to see restored in Dublin would be a mockery of Irish national aspirations.

If you remove the English army tomorrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organisation of the Socialist Republic your efforts would be in vain. England would still rule you. She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and individualist institutions she has planted in this country and watered with the tears of our mothers and the blood of our martyrs.[13]

By the same token, Connolly implied that there was little to be expected from the "Irish Language movements, Literary Societies or [1798] Commemoration Committees" of Milligan and of their mutual friends in Dublin (Arthur Griffith, Maud Gonne, and Constance Markievicz whom Connolly was to join in "to-hell-with-the-British-empire"[14] protests against Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee and the Boer War).[2]: 51, 66–69 There could be no lasting progress toward an Irish Ireland without acknowledging that, as a force that "irresistibly destroys all national or racial characteristics", capitalism was the Celtic Revival's "chief enemy".[15][12]: 17

Milligan, who deferred to the Irish Republican Brotherhood (in 1899 they had her pass her subscription list to Griffith and his new weekly, the United Irishman, the forerunner of Sinn Féin),[16] confined her response to Connolly's ambition to contest Westminster elections. Were the ISRP successful, she predicted "an alliance with the English Labour" no less debilitating than the courtship of English Liberals had proved for the Irish Parliamentary Party.[17] In the event, Ireland's first socialist party, garnering only a few hundred votes,[18]: 186 failed to elect Connolly to Dublin City Council and never exceeded more than 80 active members.[19]

Connolly was dispirited and at odds with the ISRP's other leading light, E. W. Stewart, manager of the party's paper, The Worker's Republic and also sometime candidate for the city council. He accused Stewart of "reformism",[3]: 209–212 of failing to appreciate that "the election of a socialist to any public body is only valuable insofar as it is the return of a disturber of the public peace”.[4]: 63 In 1900, Connolly had supported the American Marxist Daniel De Leon in condemning the decision by the French socialist Alexander Millerand, at the height of the Dreyfus Affair, to accept a post in Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau’s government of “Republican Defence”.[4]: 131–133

Union and party organiser

[edit]America: Industrial Workers of the World

[edit]

In September 1902, at the invitation of De Leon's Socialist Labor Party, Connolly departed for a four-month lecture tour of the United States. Addressing largely Irish-American audiences, he emphasised that he spoke for class, not country:

I represent only the class to which I belong…I could not represent the entire Irish people on account of the antagonistic interests of these classes, no more than the wolf could represent the lambs or the fisherman the fish.[4]: 149

On his return, Connolly had his resignation from the IRSP accepted without demur.[4]: 99 He returned to Scotland for the Social Democratic Federation, where, after witnessing the organisation's expulsion of "De Leonists", he decided on a future in America.[4]: 166–167

On arrival in the United States, and before he could call on his family to join him, Connolly lived with cousins in Troy, New York, and found work as a salesman for insurance companies. But by 1905, and after being elected to the national executive of the Socialist Labor Party, he had returned to political work. With De Leon's endorsement, he was an organiser for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the "One Big Union".[4]: 61–62

Finding employment with the Singer Sewing Machine in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and living in The Bronx, he befriended the young Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (daughter of a neighbouring couple from Galway),[20] who was to become the "Wobblies" chief agitator among the largely immigrant women of the east-coast textile industry.[21] Together they were supported by Mother Jones, "America’s Most Dangerous Woman”,[22] the Wobblies' co-founder and a veteran organiser for the United Mine Workers whom Connolly had learnt to admire from Ireland.[20]

With Flynn, and with ex-ILP member Patrick L. Quinlan, in 1907 Connolly formed the Irish Socialist Federation (ISF) to promote the SLP's message among Irish immigrants. It had branches in New York City and Chicago, and Connolly edited its weekly the Harp.[22][8]: 67–70

Under the influence of the IWW, a "mass movement, whose militancy was unequalled", Connolly began to turn away from what was an "unashamedly vanguard party".[23]: 28 In April 1908, and after a bitter dispute in which De Leon accused him of being a police spy,[4]: 63 Connolly left the SLP, and at its Chicago conference, the IWW expelled the party.[8]: 67 In the new year, together with Mother Jones,[20] Connolly and the ISF affiliated with the Socialist Party of America,[24] a broader coalition more tolerant of their revolutionary syndicalism.[24]

ITGWU leader in Belfast

[edit]

Through the ISF Connolly re-established links with socialists in Ireland, and in 1909 he transferred the production of the Harp to Dublin. The following year, James Larkin persuaded the Socialist Party of Ireland (SPI) to raise the funds that would enable Connolly and his family to return.[25] In January 1909, Larkin had established the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, his own model of the One Big Union.[8]: 112 The same year, 1911, in which Connolly's occupation was listed on the census return as "National Organiser Socialist Party,[26] Larkin sent him north to Belfast to organise for the ITGWU in Ulster.

In a city in which the Protestant-dominated apprenticed trades were organised in British-aligned craft unions, troops had been deployed in 1907 to break strikes Larkin had called among dock labourers, carters and other casual and general workers. Four years later, Connolly succeeded in bringing dockers out in sympathy with striking cross-channel seamen, and in the process to secure a pay increase.[27] ITGWU membership grew, and Connolly was approached by women toiling in Belfast's largest industry, linen.[12]: 109–113

The sweated trade engaged thousands of women and girls both in mills and, unprotected by the Factory Acts, as outworkers. A Belfast Trades Council sponsored Textile Operatives Society, led by Mary Galway,[28] concentrated only on the better-paid Protestant women in the making-up sections. In response to the speeding up of production in the mills and, relatedly, the fining of workers for such new offences as laughing, whispering and bringing in sweets (the creation, in Connolly words, of "an atmosphere of slavery"),[18]: 152 thousands of spinners went out on strike.

As they did not yet have the union organisation and the strike funds to sustain the action, Connolly persuaded the women to return to work and apply tactics he had learned as an organiser for the IWW. They should collectively defy the rules, so that "if a girl is checked for singing, let the whole room start singing at once; if you are checked for laughing, let the whole room laugh at once".[18]: 152 [12]: 112 He then sought to capitalise on the relative success of the tactic by building up, first with Marie Johnson and then Winifred Carney as its secretary, a new – effectively women's – section of the ITGWU, the Irish Textile Workers' Union (ITWU).[29]

In June 1913, while claiming that "the ranks of the Irish Textile Workers’ Union are being recruited by hundreds",[30] with Carney, Connolly produced a Manifesto to the Linen Slaves of Belfast (1913).[31] It revealed their frustration as organisers: if the world deplored their conditions, the women were told that it also deplored their "slavish and servile nature in submitting to them".[32]: 29 The Textile Workers' membership may not have greatly exceeded the 300 subscribed under Johnson in Catholic west Belfast.[33][8]: 99 To Carney, Connolly conceded that the union's survival was largely a matter of "keeping the Falls Road crowd together".[29]

Sectarian division within the labour movement in Belfast had been heightened by the return of Home Rule to the political agenda (from 1910, a Liberal government was again dependent on Irish votes). When, in the summer of 1912, a Home Rule Bill was introduced, loyalists forced some 3,000 workers out of the shipyards and engineering plants: in addition to Catholics, 600 Protestants targeted for their non-sectarian labour politics.[34] In this environment, Connolly found himself increasingly confined to organising, and to addressing meetings, in the Catholic districts of the city.[8]: 103–104 Even here he was pursued by what he described as "social and religious terrorism".[35]

Connolly had to find some "corner of the Catholic ghetto outside the political preserve of Joseph Devlin MP".[8]: 103 Although a sometime ally (Devlin initiated Home Office inquiry into conditions in the linen mills),[8]: 99 the Belfast West MP was leader both of those Connolly viewed as "the conservatives of a belated Irish capitalism", the United Irish League, and those who he dismissed as "Green" Orangemen, the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Together, Connolly found them capable of bringing "every species of intimidation and bribery . . . to bear upon Catholics who refused to bow to the dictates of the official Home Rule gang".[35]

Dublin lock-out

[edit]

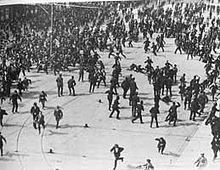

On 29 August 1913, Larkin recalled Connolly to Dublin. The success of the ITGWU in signing up thousands of unskilled men and women had elicited a particularly aggressive reaction from employers. Beginning with, and led by, the owner of the tramway company, William Murphy, they dismissed those who refused to renounce the union and replaced them with scab labour brought in from elsewhere in the country or from Britain.[36] By the end of September, the combination of the "lock out", the sympathetic strikes Larkin called for in response, and their knock-on effects, had placed upwards of 100,000 people (workers and their families, a third of the city's residents) in need of assistance.[37]

Early in the conflict Connolly freed himself from police detention through a week-long hunger strike, a tactic borrowed from the British suffragettes. However, from October Larkin was held on charges of sedition. This left Connolly to respond to an intercession by the Catholic Church.[38]: 65

In the hope of replicating a tactic that for Elizabeth Gurley Flynn had turned the tide in the recent, and celebrated, textile strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts,[39] Dora Montefiore had devised a children's "holiday scheme".[40] The poorly nourished children of the locked-out and striking workers were to be billeted with sympathetic families in England.[41] On the grounds that their hosts were not guaranteed to be Catholic, the Church objected and Hibernian crowds gathered at the docks to prevent the children's "deportation".[42][43] Connolly, who had been wary from the first, cancelled the scheme, but nonetheless sought to score a point against the clericalist opposition by telling his people to ask the archbishop and priests for food and clothing.[2]: 333

Connolly and Larkin had shown a willingness to negotiate on the basis of an inquiry into the dispute by the Board of Trade. While critical of the ITGWU's employment of the "sympathetic" strike, it concluded that employers were insisting on an anti-union pledge that was "contrary to individual liberty", and that "no workman or body of workmen could reasonably be expected to accept”. The employers were unmoved.[12]: 142–143

After the ITGWU-controlled Dublin Socialist Party failed in the January 1914 municipal elections to register support for the strike,[44]: 163 and the Trade Union Congress in England had declined Larkin and Connolly's plea for additional support and funding, the workers began to drift back, submitting to their employers. Exhausted, and falling into bouts of depression, Larkin took a declining interest in the beleaguered union, and eventually in October accepted an invitation from "Big Bill" Haywood of the IWW to speak in the United States. He did not return to Ireland until 1923.[45] His departure left Connolly, in charge not only of the ITGWU with its headquarters at Liberty Hall, but also of a workers' militia.[2]: 333

Easter Rising

[edit]Irish Citizen Army

[edit]

First floated as an idea by George Bernard Shaw,[46] the training of union men as force to protect picket lines and rallies was taken up in Dublin by "Citizens Committee" chair, Jack White, himself the victim of a police baton charge.[3]: 552–553 In accepting White's services, Connolly made reference to the national question: "why", he asked "should we not train our men in Dublin as they are doing in Ulster".[2]: 240 In the north, the Unionists, labour men among them,[47] were forming the ranks of the Ulster Volunteers. The Irish Citizen Army (ICA) began drilling in November 1913, but then, after it had dwindled like the strike to almost nothing, in March 1914 the militia was reborn, its ranks supplemented by Constance Markievicz's Fianna Éireann nationalist youth.[48][18]: 198

After the return to work, the command of the ICA divided on the militia's future, and in particular on policy toward the Irish Volunteers, the much larger nationalist response to the arming of Ulster Unionism (and of which Markievicz was also a member). Secretary to the ICA Council, Seán O'Casey, described the formation of the Irish Volunteers as "one of the most effective blows" that the ICA had received. Men who might have joined the ICA were now drilling – with the blessing of the IRB – under a command that included employers who had locked out men trying to exercise "the first principles of Trade Unionism".[49] When it became apparent that Connolly was gravitating towards an IRB strategy of cooperation with the Volunteers, O'Casey and Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, the Vice President, resigned, leaving Connolly in undisputed command.[50]

On 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. The Home Rule Bill received royal assent, but with a suspensory act delaying implementation for duration (and with the reservation that the question of Ulster's inclusion had still to be resolved). Leader of the IPP, John Redmond, then split the Irish Volunteers by urging them (in the hope of securing Britain's good faith) to rally to the British Army's colours.[51] The vast majority heeding his call – some 175,000 men – reformed themselves as the National Volunteers. This left 13,500 to reorganise under the nominal command of Eoin MacNeill of Gaelic League but, in key staff positions, directed by undercover members of the IRB's Military Council: Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh and Joseph Plunkett.[52]

Urges "revolutionary action"

[edit]In October 1914, Connolly assumed the presidency of the Irish Neutrality League (chairing a committee that included Arthur Griffith, Constance Markievicz and Francis Sheehy-Skeffington),[53] but not as a pacifist. He was urging active opposition to the war, and acknowledged that this amounted to "more than a transport strike". Stopping the export of foodstuffs from Ireland, for example, might involve "armed battling in the streets".[12]: 181 In the Irish Worker he had already declared that if, in the course of Britain's "pirate war upon the German nation", the Kaiser landed an army in Ireland "we should be perfectly justified in joining it".[54] A further editorial in the ITGWU paper betrayed his exasperation with the "jingoism" of the British labour movement.[12]: 180–181 It suggested that insurrection in Ireland and throughout the British dominions might be required “to teach the English working class they cannot hope to prosper permanently by arresting the industrial development of others”.[55]

In December, the Irish Worker was suppressed and in May 1915 Connolly revived his old ISRP title, Workers' Republic. Accompanied by the martial-patriotic poetry of Maeve Cavanagh, Connolly's editorials continued to urge Irish resistance,[56] and on the express understanding that this could not "be conducted on the lines of dodging the police, or any such high jinks of constitutional agitation".[57] He cautioned that those who oppose conscription (the prospect that was drawing crowds to the meetings, the marches and parades of the Irish Citizen Army and of the Volunteers) "take their lives in their hands" (and, by implication, that they should organise accordingly). In December 1915, Connolly wrote: “We believe in constitutional action in normal times, we believe in revolutionary action in exceptional times. These are exceptional times".[58]: 187

In February 1916, Connolly proposed, that with "thousands of Irish workers" volunteering to fight for British Crown and Empire, only the "red tide of war on Irish soil" would enable the nation to "recover its self-respect".[59][44]: 172

Relations with the IRB

[edit]Connolly was aware of, but not privy to, discussions within the IRB on prospects for a national rising. Patrick Pearse cautioned his colleagues on treating with Connolly: "Connolly is most dishonest in his methods. He will never be satisfied until he goads us into action, and then he will think most of us too moderate and want to guillotine half of us".[60]: 168

By the New Year, believing the Irish Volunteers were dithering, Connolly was threatening to rush Dublin Castle, around which he had already deployed his ICA on nightly manoeuvres. Determined to safeguard their plans for an insurrection at Easter, Seán Ó Faoláin claims that the IRB had Connolly "kidnapped".[18]: 205 A unit of Volunteers had been mobilised to arrest Connolly had he refused to meet with the IRB Council, but Patrick Pearse, Tom Clarke and the other IRB leaders resolved matters by finally taking Connolly into their confidence.[61]

Connolly was conscious that his new allies had, for the most part, been silent during the lock-out in 1913.[49] Labour was not their cause, so that when he himself had proposed a programme for the Irish Volunteers in October 1914, he had confined it to political demands: "repeal of all clauses of the Home Rule Act denying Ireland powers of self-government now enjoyed by South Africa, Australia or Canada".[62][44]: 167–168 According to Desmond Greaves,[63]: 142 a week before the Rising Connolly advised his 200 ICA volunteers that, as they were "out for economic as well as political liberty", in the event of victory they should "hold on to" their rifles.[4]: 403

Easter week 1916

[edit]

On 14 April 1916, Connolly summoned Winifred Carney to Dublin where she prepared his mobilisation orders for the Irish Citizen Army (ICA). Ten days later, on Easter Monday, with Connolly commissioned by the IRB Military Council as Commandant of the Dublin Districts, they set out for the General Post Office (GPO) with an initial garrison party from Liberty Hall. Carney (armed with a typewriter and a Webley revolver) served as Connolly's aide de camp with the rank of adjutant[64] She was seconded in that role, for the first two days, by Connolly's 15 year-old son Roddy.[65]

From the steps of the GPO, Patrick Pearse (President and Commander-in-Chief) read the "Proclamation of the Irish Republic". Connolly had contributed to the final draft, which declared "the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland" and, in a phrase that he had often been used, a "resolve to pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole nation and of all its parts".[38]: 87 In a further symbolic gesture of labour's stake in the rebellion, Connolly sent the Starry Plough flag, the symbol of Irish labour, to be hoisted by his men over the Imperial Hotel, owned by the man who had organised their defeat in 1913, William Murphy.[2]: 332

By some accounts the rebel strategy of occupying the GPO and other public buildings in the city centre, had been informed by Connolly's belief that the British were unlikely to rely on artillery,[3]: 679 that a regular bombardment of the city would have been possible only if, abandoning their businesses and property, the section of the population loyal to the government was outside insurgent lines.[4]: 193 Connolly's biographer, Samuel Levenson records an exchange between Volunteers after a British gunboat began shelling their positions from the Liffey: "General Connolly told us the British would never use artillery against us". "He did, did he? Wouldn't it be great now if General Connolly was making the decisions for the British".[2]: 308

Leading men on the street and supervising the construction of barricades, he was twice wounded on the Thursday. Carney refused to leave his side,[64] and was with him the following day, Friday 29 April, when, carried on a stretcher, he was among the last to evacuate from the GPO, its upper floors burning, to Moore Street.[3]: 408–412. There, with Seán Mac Diarmada and Joseph Plunket, Connolly persuaded Pearse, over Tom Clarke's objection, to ask the British for terms.[66]: 304–305 Satisfied that "the glorious stand which has been made by the soldiers of Irish freedom" was "sufficient to gain recognition of Ireland's national claim at an international peace conference", and "desirous of preventing further slaughter of the civilian population", Pearse recorded the "majority" decision.[66]: 305 Elizabeth O'Farrell, sent under a white flag to the British commander, Brigadier-General Lowe,[67] came back with a demand for unconditional surrender which, within the 30 minute time limit imposed, Pearse conceded.[66]: 307

As he was being returned to a stretcher to be carried toward the British lines, Connolly told those around him not to worry: "Those of us that signed the proclamation will be shot. But the rest of you will be set free."[2]: 333

Court martial and execution

[edit]

Connolly was among 16 republican prisoners executed for their role in the Rising. Executions in Kilmainham Gaol began on 3 May 1916 with Connolly's co-signatories to the Proclamation, Patrick Pearse, Tom Clarke and Thomas McDonagh, and ended with his death and that of Seán Mac Diarmada on 12 May. Roger Casement, who had run German guns for the Rising, was hanged at Pentonville Prison, in London, on August 3. Unable to stand because of his wounds (his foot had turned gangrenous), Connolly had been placed before a firing squad tied to a chair.[68] His body was placed, without rite or coffin, with those of his comrades in a common grave at the Arbour Hill military cemetery.[69]

In a statement to the court martial held in Dublin Castle on 9 May, he proposed offering no defence, save against "charges of wanton cruelty to prisoners”,[70] and he declared:[71]

We went out to break the connection between this country and the British Empire, and to establish an Irish Republic. We believed that the call we then issued to the people of Ireland, was a nobler call, in a holier cause, than any call issued to them during this war, having any connection with the war. We succeeded in proving that Irishmen are ready to die endeavouring to win for Ireland those national rights which the British Government has been asking them to die to win for Belgium. As long as that remains the case, the cause of Irish freedom is safe.

The night before his execution, he was permitted a visit by his wife Lillie and their 8 year old daughter, Fiona (whose abiding memory of her father was to be his laughter).[72] He is said to have returned to the Catholic Church in the few days before his execution.[73][74] A Capuchin, Father Aloysius Travers administered absolution and last rites. Asked to pray for the soldiers about to shoot him, Connolly said: "I will say a prayer for all men who do their duty according to their lights."[75]

There was disquiet at Connolly's execution. In Parliament the government was pressed as to whether there was "precedent for the summary execution of a military prisoner dying of his wounds".[68] But at the time, the greater outrage was over the executions of William Pearse, put to death, it was thought, simply because he was the brother of the rebel leader, and Major John MacBride who played no part in planning the Rising but had fought against Britain in the Boer War.[76]

Despite the initial public hostility toward the rebels and the destruction they had brought upon Dublin, after the first executions of Pearse, Clarke and MacDonagh, John Redmond warned the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, that any further executions would make his position, and that of any other constitutional party or leader in Ireland, "impossible”.[77]

Political thought

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Irish republicanism |

|---|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

Socialism and nationalism

[edit]The nature of Connolly's socialism, and its role in his decision to join the IRB in the Easter Rising, was disputed by his Socialist contemporaries in both Europe and the United States. It is the central point of contention in the extensive literature that has developed since on his political life and thought.[44]: 151 [78]: 85

Writing in 1934, Seán Ó Faoláin described Connolly's political ideas as:

an amalgamation of everything he had read that could, according to his viewpoint, be applied to Irish ills, a synthesis of Marx, Davitt, Lalor, Robert Owen, Tone, Mitchel and the rest, all welded together in his Socialist-Separatist ideal. He favoured Industrial unionism as the method of approach to what he called variously, the Workers' Republic, the Irish Socialist Republic, the Co-operative State, the Democratic Co-operative Commonwealth... [The unions] would be he means of popular representation in the Workers' Parliament; and they would be the power controlling the national wealth ... In a word he believed in vocational representation combined with "all power to the Unions".[18]: 189

While he never had the opportunity to apply and test his principles even on a small scale, Connolly "at least [had] a point of view" and a "definite idea of what he meant by such terms as 'a Republic', 'Freedom', 'Emancipation' [and] 'Autonomy'".[18]: 190 But Ó Faoláin argues that in the end Connolly's social-emancipatory ideas proved to be secondary to his nationalism. The night before he was shot, Connolly said to his daughter Nora: "The Socialists will not understand why I am here; they forget I am an Irishman". For Ó Faoláin this was an admission that "he had, in point of fact, gone over to nationalism and away from socialism".[18]: 193

Some of Connolly's contemporaries suggested that there was no inconsistency: Connolly's socialism was itself merely a form of militant nationalism. Invoking Connolly at the inaugural meeting of Fianna Fáil in 1926, in support of his protectionist programme for national development, Éamon de Valera implied that Connolly's principal purpose in calling for a worker's republic was to complete the break with England.[79]: 46 Constance Markievicz was also to interpret Connolly's socialism in purely national, purely Irish, terms. Seizing on Connolly's portrait of Gaelic society in The Reconquest of Ireland,[80] she summarised his doctrine as the "application of the social principle which underlay the Brehon laws of our ancestors".[81]

At the same time, there were writers who, convinced that "Connolly's Irish Catholicism had not been irrevocably blemished by atheistic Marxism",[79]: 46 found parallels between his commitment to industrial unionism and the corporatist doctrines Pope Leo XIII enunciated in his encyclical Rerum novarum (1891).[82][83]

Beginning in 1961, with the publication a major new biography by Desmond Greaves, there was a concerted effort to rehabilitate Connolly as a revolutionary socialist.[84]: 49–51 [85]: 36–37 [79] Greaves proposed that with the onset of the European war, Connolly's thought had run "parallel with Lenin's"; and reached the same conclusion:[4]: 353 "Whoever wishes a durable and democratic peace must be for civil war against the governments and the bourgeoisie" (Lenin, "Turn Imperialist War into Civil War", 1915).[86] Greaves is the source for Connolly's oft-quoted "hold on to your rifles" admonition to his ICA volunteers, which might suggest that Connolly did see the Easter Rising as the prelude to this larger revolutionary struggle.[63]: 142

While The Life and Times of James Connolly[87] remains a standard reference,[2]: 204 [63]: 140 there have been objections to pressing Connolly into a Leninist mold.[63][84]: 66–67 Connolly's revolutionary outlook remained that of the syndicalism he had acquired in America, although in 1916 he entertained no suggestion of Irish workers being organised to seize control of their workplaces.[23][88] He was concerned, rather, with their quiescence in the war against Germany.[44] This was viewed by Connolly, not as a contest of rival imperialisms with no democratic principle at stake, but as a war in which, as the primary aggressor, Britain had presented an Ireland willing to strike for its freedom with a legitimate continental ally.[12]: 181–184 [84]: 66–67

Connolly's understanding of the agrarian nature of nationalist Ireland, and of Ulster unionism, which deprived it of Belfast and its industrial hinterland, has also been subject to comment and revision.

Revolutionary syndicalism

[edit]

Greaves concedes that there are formulations in Connolly's thinking that "smack of syndicalism"[4]: 245 —that is, of faith in the ability of the working class to secure a socialist future on the strength, not of a revolutionary party, but of their own labour-union democracy. Lenin had praise for De Leon's contribution to socialist thought,[89]: 42 but Connolly broke with De Leon precisely on the issue of industrial unionism.[24][89]: 25–29

In 1908, Connolly accused De Leon of knocking "the feet from under" his party's alliance with the IWW by arguing that, as prices rise with wages, the gains the union secures for labour are only nominal. The implication was that the One Big Union was merely a "ward-heeling club" for the SLP, a place from which militants could be recruited to the real task: building a party to take state power.[90]

Since it suggests that within capitalism there is no prospect of the working class improving its position, Connolly allowed that the "theory that a rise in prices always destroys the value of a rise in wages" sounds "revolutionary". But it was not Marxist and not true.[3]: 231 The value of labour is not fixed, but is the subject of a continuous struggle. It is in this struggle that workers acquire the organisational strength and the confidence to bring capital to heel, and to extend their own control of production and distribution.[91]

In a last statement of his credo, The Re-conquest of Ireland (1915), Connolly affirmed that the outcome of this struggle, the worker's republic, is not an overweening state. Rather it is an industrial commonwealth in which "the workshops, factories, docks, railways, shipyards, &c., shall be owned by the nation, but administered by the Industrial Unions of the respective industries".[92]

An early compiler of his ideas, notes that Connolly "nowhere attempts to explain how the general interests of the State, as distinguished from specific interests of the Industrial Unions, are to be provided for". It was only certain that Connolly was not a "state socialist".[93]: 536 Connolly was, himself, confident that his:[23]: 31 :

... conception of Socialism destroys at one blow all the fears of a bureaucratic state, ruling and ordering the lives of every individual from above, and thus gives assurance that the social order of the future will be an extension of the freedom of the individual, and not a suppression of it.[91]

In his last six years, Connolly had devoted his energies almost entirely to the ITGWU and to the Irish Citizen Army. A "pairing of union and militia" is central to syndicalist scenarios for social revolution.[23]: 9, 17, 28–29 But Connolly knew that "his union, the ITGWU . . ., weakened by the industrial struggles of 1913-14, was not up to the effort of seizing docks, railways, shipping etc.".[94]: 121–122 He made no attempt, prior to or during the Rising, to appeal to workers to join the insurgency. In an address published just one week before the Rising on the forthcoming congress of the Irish TUC, there is no intimation of the impending action. In reference to the war, Connolly's only advice was that the congress should proceed in August as planned.[88]

A two-stage struggle

[edit]At the beginning of 1916, Connolly drew "a crucial distinction between the struggle for socialism and for national liberation".[44]: 169 In the Irish Worker (23 January) he wrote:

Our programme in time of peace was to gather in the hands in Irish trade unions the control of all the forces of production and distribution in Ireland . . . [but] in times of war we should act as in war. . . . While the war lasts and Ireland still is a subject nation we shall continue to urge her to fight for her freedom. . . . The time for Ireland's battle is NOW.[44]: 169

His calculation was not based alone on the strategic opportunity presented by Britain's engagement with Germany. Connolly had described John Redmond's pact with the government as "the most gigantic, deep-laid and loathsome attempt in history to betray the soul of a people".[44]: 167 At the beginning of February 1916, he acknowledged that the pact was delivering the working class, and not least by means of simple bribery:[44]: 172

We have said that the Working Class was the only class to whom the word "Empire" and the things for which it was the symbol did not appeal . . . [and] therefore, from the intelligent working class could alone come the revolutionary impulse. . . . But if the Militant Labour Leaders of Ireland have not apostatised the same cannot be said of the working class as a whole . . . . For the sake of a few paltry shillings per week thousands of Irish workers have sold their country in the hour of their country's greatest need and hope. For the sake of a few paltry shillings Separation Allowance thousands of Irish women have made life miserable for their husbands with entreaties to join the British Army.[95]

In Erin's Hope (1897), Connolly had claimed that socialists would succeed where the Fenians, and the Young Irelanders before them, had failed, in preparing "the public mind for revolution".[44]: 156 For this, they would rely on the militant organisation of labour, neither seeking nor accepting the cooperation of men whose ideals were not their own, and with whom they might therefore "be compelled to fight at some future critical stage of the journey to freedom". To this category, Connolly assigned "every section of the propertied class".[44]: 156 John Newsinger argues that such talk was now put aside. Connolly embraced "the conception of revolution that prevailed in the inner circles of the IRB: that a small minority must be prepared to sacrifice itself in order to save the soul of the nation". It was, he suggests, the "politics of despair".[44]: 170 Austen Morgan similarly concludes Connolly "collapsed politically as a socialist.[8]: 199 Unable to sustain his faith in proletarian action, that he died "unapologetic Fenian".[79]: 45–46

Noting that, two weeks before the Rising, Connolly, was still affirming that "the cause of labour is the cause of Ireland, the cause of Ireland is the cause of labour" and that the two "cannot be dissevered",[96] Greaves continued to insist that little had changed in Connolly's fundamental thinking.[94]: 121–122 R.M. Fox considers the view that Connolly "allowed himself to be dragged away from his labour convictions" to be "foolish" and "superficial", arguing that under the unique conditions of the Great War he was compelled to "force the independence issue to the point of armed struggle".[97] But, for Richard English, while this may have been so, it is Connolly's failure "to persuade any but a tiny number of the Irish people" of his argument that accounts for his "gesture" in 1916. Acceding to the IRB's "inclusive, cross-class approach to the nation", his hope was only of an "eventual" vindication[98] of his belief that, once national rebellion had secured "the national powers needed by our class", social revolution would follow.[96]

Farm-labour cooperation

[edit]Apart from what he may have witnessed as a soldier, Connolly's only sustained experience of rural Ireland was three weeks spent in County Kerry in 1898 reporting on famine conditions for De Leon's Weekly People.[99]: 30 Connolly concluded that "the root cause" of the distress was not landlordism per se or an "alien government", but rather a "system of small farming and small industry" in which the Irish peasant "reaps none of the benefits of the progress . . . [and] organisation of industry".[99]: 39

This was the seemingly orthodox Marxist view to which Connolly was already committed. In Erin's Hope (1897) he had proposed that "the day of the small farmers, as of small capitalists, is gone" and that salvation lay in "the nationalisation of land in the hands of the Irish state". From Kerry, he wrote more loosely of the Socialist Republic organising greater "co-operative effort",[99]: 39 [100]: 13 but in either case it was an analysis that suggested that "the most important struggles for the Irish peasantry would occur not in the countryside, but between labour and capital in the cities". There is no discussion of the role the rural population itself might play in the creation of the new republic.[99]: 40

By the time of his return from America in 1910, the combined effects of continued emigration and land reform was effecting a profound social transformation.[99]: 40 [8]: 198 In Labour in Irish History (1910), Connolly recalls the words of Wolfe Tone: “Our freedom must be had at all hazards. If the men of property will not help us they must fall; we will free ourselves by the aid of that large and respectable class of the community – the men of no property.”[101] But after the Wyndham Act (1903), the peasant "was, or else was well on the way to becoming, a freehold farmer--a man of property". Unmoved by what Connolly supposed was their "memory of the common ownership and common control of land by their ancestors",[92]: 318 it was a status they would defend it with tenacity.[102]: 250 [103]

A "large self-confident class of farmer owners" was shifting the balance of class forces in Catholic Ireland against Connolly's identification of the national cause with labour. Their emancipation from taxation imposed in working-class interest would be "the main economic achievement of independence".[104] This was not a prospect admitted by Connolly. He suggested rather a farm-labour alliance. A feature of the transition from tenancy to ownership in countryside was the establishment of creameries and other agricultural co-operatives. Participation was often reluctant, and generally failed to support broader networks, but the image was created abroad of Irish farmers as "co-operative trailblazers".[105] In The Reconquest of Ireland (1915), Connolly celebrates the development and, recalling the co-operative stores his union had opened in Dublin after the Lock-out, "confidently" predicts that, "in the very near future", the labour movement will create its own "crop of co-operative enterprises". The stage would then be set for town and country to heal their "latent antagonism" and converge on a common ideal — the "Co-operative Commonwealth".[92]: 320–321 [106]: 52–55 [107]

Ulster unionism

[edit]

In 1898 Connolly had cited "the Protestant workmen of Belfast, so often out on strike against their Protestant employers, and the role their Protestant ancestors had played a 100 years previously in the rebellion against the British Crown, as a demonstration of what "precious little bearing" the question of religious faith has in the struggle for freedom.[108] Later, when in Belfast for the Socialist Party and the ITGWU, he identified "religious bigotry" as the one obstacle remaining to the acceptance of Irish self-government and thus to the achievement of socialist unity on a separate all-Ireland basis.[109] But he understood this as a political force arising, not from confessional differences, but from the deliberate recall and accentuation of ancient native-planter divisions.[60]: 144–146

As the new Home Rule bill safely progressed through Westminster, Connolly appeared to concede the objection of William Walker, the Protestant leader of the Independent Labour Party in Belfast, who argued for British Labour and British social legislation.[110]: 21 He suggested that having "voted against the Right to Work Bill, the Minimum Wage for Miners, and the Minimum Wage for Railwaymen, [and] intrigued against the application to Ireland of the Feeding of Necessitous School Children and the Medical Benefits of the Insurance Act,[111] in a parliament of their own Home Rulers would likely set a bad example to "reactionists everywhere".[112] He also allowed religious bigotry was not alone the mark of Empire loyalists: Connolly had applauded the even-handedness of the Grand-Master of the Independent Orange Order, Lindsay Crawford, in castigating sectarian influences — both "Orange and Green".[35] But in an "ill-tempered and discursive" exchange with Walker,[113] Connolly admitted no case for labour sticking with the Imperial Parliament.[114][60]: 104

Labour unionism was still unionism and, no matter how reactionary nationalism might appear under its current leadership, unionism was more reactionary still.[115][116] It represented an Orange-inflected Protestantism that had become "synonymous" with what Catholicism represented in much of the rest of Europe; that is, with "Toryism, lickspittle loyalty, servile worship of aristocracy and hatred of all that savours of genuine political independence on the part of the lower classes".[117] Thus it was that he had encountered in Ireland's industrial capital, not what socialist theory would have predicted, its most politically-advanced working class, but rather those he despairingly characterised as "least rebellious slaves in the industrial world".[118][116]

Walker maintained that it was as an internationalist that he supported the union with Great Britain. Connolly replied that the only true socialist internationalism lay in a "free federation of free peoples".[109][119] That the Protestant working people of Ulster could regard themselves as a free people within the United Kingdom, he dismissed, effectively, as "false consciousness".[3]: 21 But as it served only the interest of their landlords and employers, it could not be long sustained.[60]: 113 Already, in 1913, in series strikes in Belfast and Larne, Connolly saw evidence of Protestant workers returning to the class struggle.[84]: 16 [111] He confidently predicted that suspicion of their Catholic fellow workers would "melt and dissolve",[44]: 164–165 and that their children would come to laugh at the Ulster Covenant.[3]: 485

In April 1912, four of the five Belfast branches of the ILP attended a unity conference called by the SPI in Dublin and agreed to form an Independent Labour Party of Ireland.[120]: 135 But sensitive to the unpopularity of Home Rule they did not carry their commitment over, when in May, Connolly secured a resolution at the Irish Trades Union Congress in favour of an Irish Labour Party without ties to the ILP or other British groups.[12]: 120–121 Instead (joined in time by Winifred Carney)[121] they adhered to what in Belfast became, after partition, the Northern Ireland Labour Party.[122]

Socialism and religion

[edit]In 1907, Connolly confessed that while he "usually posed as a Catholic", he had not done his "duty" for fifteen years, and had "not the slightest tincture of faith left".[3]: 679 Yet he could not accept De Leon's insistence that a socialist party be as "intolerant as science" of deviations from strict materialism. Connolly opposed clericalism.[123] He argued that Irish Catholics could in all conscience reject their bishops' dealings with the British authorities,[8]: 59 and proposed that Irish schools be free of church control.[35] But claiming "conformity with the practice of the chief Socialist parties of the World", he declared religion a private matter outside the scope of socialist action.[124][2]: 112–113

Socialism, is a bread and butter question. It is a question of the stomach; it is going to be settled in the factories, mines and ballot boxes of this country and is not going to be settled at the altar or in the church.[125]

In 1910, he published Labour, Nationality and Religion in which he defended socialists against the clerical charge that they are "beasts of immorality". He noted, for example, that the "enormous increase of divorces [in the United States] was almost entirely among the classes least affected by Socialist teaching".[123] But, at the same time, he argued that there was an egalitarian and humanitarian impulse in Christianity that provided a moral bridge to socialism, and could positively contribute to its advance.[126]

In either case, Connolly believed it was an unnecessary and strategic mistake for socialists to risk popular support by deliberately outraging religious opinion.[2]: 112 He had refused to join De Leon in entertaining August Bebel's ideas on polyamorous marriage.[124][8]: 52 Doing so, he argued, was simply putting "a weapon" into the hands of their enemies "without obtaining any corresponding advantage".[90]

Emancipation of women

[edit]

In a campaign to raise funds for the Dublin strikers in 1913, Connolly shared a platform at London's Royal Albert Hall with Sylvia Pankhurst.[46] He took the occasion to declare that he stood for "opposition to the domination of nation over nation, of class over class, or of sex over sex".[12]: 145 He had supported the Suffragette movement, and worked alongside women in the labour movement. His Irish Citizen Army had the distinction of giving women officer rank and duty[18]: 213 [127] Francis Sheehy-Skeffington was convinced that, of "all the Irish labour men", Connolly was "the soundest and most thorough-going feminist".[128]

In The Reconquest of Ireland (1915), Connolly traced oppression of women, like the oppression of the worker, to “a social and political order based upon the private ownership of property”. If the "worker is the slave of capitalist society, the female worker is the slave of that slave".[92]: 292 He would have little use for any form of Irish state that did not not "embody the emancipation of womanhood?".[128] However, socialism would solve only "the economic side of the Woman Question": "the question of marriage, of divorce, of paternity, of the equality of woman with man are physical and sexual questions, or questions of temperamental affiliation as in marriage," would "still be hotly contested".[60]: 46 There was still a private sphere in which women themselves would complete the struggle for their own emancipation. "None", he remarked, is "so fit to break the chains as they who wear them, none so well equipped to decide what a fetter is”.[128]

Rejection of antisemitism

[edit]During his 1902 election campaign in the Wood Quay ward in Dublin, in which many streets were occupied by Jewish immigrants from Russia, Connolly's campaign became the first in Irish history to distribute leaflets in Yiddish. The leaflet condemned antisemitism as a tool of the capitalist class.[129]: 129–130 [3]: 171

Connolly sharply criticised the overtly anti-semitic tone of the British Social Democratic Federation's publications during the Boer War, arguing that they had attempted to "divert the wrath of the advanced workers from the capitalists to the Jews". His own editorship, however, did not exclude the possibility of anti-Jewish tropes. In the Workers Republic readers were asked to place themselves in the position of the Boers: "Supposing your country was invaded by a mob of Jews and foreign exploiters ... What would you do?".[129]: 121–122 During the Cork lock-out of 1909, Connolly's Harp (the journal of the Irish Socialist Federation) featured an article denouncing "patriotic Irish capitalists" for importing "wholesale scab Jews to break the strike of Irish workers".[130]

In 1898, Workers Republic published an article "The Ideal Government of the Jew", advocating "the establishment of an Isrealitish [sic] nation in Palestine".[129]: 120–121 But two years later, Connolly himself was to write positively about the "remarkable" development in the Russian Empire of the Jewish Labour Bund.[129]: 124–125 Part of Russian Social Democracy, the Bund was anti-Zionist.[131]

Family

[edit]James Connolly and his wife Lillie had seven children.[132] The eldest, Mona, died on the eve of the family's departure to join Connolly in America in 1904 at the age of 13, the result of an accident with scalding laundry water.[133]

In Belfast, Nora and Ina (1896–1980) were active, with Winifred Carney, in Cumann na mBan and carried reports from the north to Pearse and their father the week before the rising in Dublin. Later, Nora was involved with her younger brother Roddy in efforts to promote a republican-socialist movement,[134] but after the splintering of the Republican Congress in 1934 they went their separate ways. Roddy ended his political life as chairman of the Irish Labour Party[135] and, the year before her death, Nora made an appearance at the Ardfheis of (Provisional) Sinn Féin.[136]

In Belfast, Aideen (1895–1966) was also in Cumann na mBan.[137] She married a Hugh Ward in Naas and had five children.[138] Moira (1899–1958) became a doctor and married Richard Beech[139] (an English syndicalist who, like Roddy, in 1920 attended the World Congress of the Comintern).[140] Connolly's youngest daughter, Fiona Connolly Edwards (1907–1976) also married in England, was active in the trade-union, and anti-partition, movements and assisted Desmond Greaves in his biographies both of her father and of the executed anti-Treaty republican, Liam Mellowes.[141]

Brian Samuel Connolly Heron (Brian o h-Eachtuigheirn), the son of Ina Connolly and Archie Heron, Connolly's grandson, was an organiser for the United Farm Workers in California. He was also a founding member in the United States of the National Association for Irish Justice which, in 1969, gained recognition as the U.S. support group for the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association.[85]: 115–116 [142] Connolly's great grandson, James Connolly Heron, has edited a compilation of his papers,[143] and is active in the campaign to preserve the historical integrity of Moore Street, where Connolly and Pearse took their final stand in 1916.[144]

In their last interview, Connolly urged his wife to return with the younger children to the United States, but she failed to secure the necessary passport. This was despite the assurance of General Sir John Maxwell that she was "a decent humble woman who would be incapable of platform oratory in America".[145]

Remaining in Dublin, in August 1916 Lillie Connolly was received into the Catholic Church, Fiona her sole witness.[72] She did not make public appearances but when she died in 1938 she was accorded a state funeral.[146]

Memorials

[edit]Ireland

[edit]In 1966, to mark 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising, Connolly Station, one of the two main railway stations in Dublin, and Connolly Hospital, Blanchardstown, were named in his honour.

In 1996, a bronze statue of Connolly, backed by the symbol of the Starry Plough, was erected outside the Liberty Hall offices of the SIPTU trade union, in Dublin.

In 2019, Irish President Michael D. Higgins opened the Áras Uí Chonghaile | James Connolly Visitor Centre on the Falls Road in Belfast, close to where the labour leader had lived in the city. Developed with funding from Belfast City Council and from North American labour unions, the centre offers an interactive exhibit dedicated to Connolly's life and work.[147] Before it stands a life-size bronze of Connolly, originally unveiled in front of the Falls Community Council offices in 2016 by the Northern Ireland Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure minister Carál Ní Chuilín, and by his great-grandson, James Connolly Heron.[148]

In July 2023, a plaque was unveiled by the Dublin City Council at Connolly's former residence on South Lotts Road in Ringsend.[149]

Scotland

[edit]In the Cowgate area of Edinburgh where Connolly grew up there is a likeness of Connolly and a gold-coloured plaque dedicated to him under the George IV bridge.[150]

United States

[edit]In 1986, a bust of Connolly was erected in Riverfront Park in Troy, New York, where he had lived on first emigrating to the United States in 1904.[151]

In 2008, a full-figure bronze of Connolly was installed in Union Park, Chicago near the offices of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers.[152]

Writings

[edit]- Connolly, James. 1897. "Socialism and Nationalism". The Shan van Vocht. 1 (1).

- Connolly, James. 1897. Erin's Hope: The Ends and the Means (republished as The Irish Revolution, c. 1924)

- Connolly, James. 1898. "The Fighting Race". Workers' Republic, 13 August.

- Connolly, James. 1901. The New Evangel, Preached to Irish Toilers, (first appeared in Workers’ Republic, June–August 1899).

- Connolly, James. 1909. Socialism Made Easy, Chicago.

- Connolly, James. 1910. Labour in Irish history (republished 1914)

- Connolly, James. 1910. Labour, Nationality, and Religion (republished 1920)

- Connolly, James. 1911. "Plea For Socialist Unity in Ireland". Forward, 27 May

- Connolly, James. 1913. "British Labour and Irish Politicians". Forward, 3 May.

- Connolly, James. 1913. "The Awakening of Ulster's Democracy". Forward, 7 June

- Connolly, James. 1913. "North East Ulster". Forward, 2 August.

- Connolly, James. 1914. "Labour in the new Irish Parliament". Forward , 14 July

- Connolly, James . 1914. "The hope of Ireland". Irish Worker, 31 October.

- Connolly, James. 1914. The Axe to the Root, and, Old Wine in New Bottles (republished 1921)

- Connolly, James. 1915. The Re-Conquest of Ireland (republished 1917)

- Ryan, Desmond (ed.). 1949. Labour and Easter Week: A Selection from the Writings of James Connolly. Dublin: Sign of the Three Candles

- Edwards, Owen Dudley & Ransom, Bernard (eds.). 1973. Selected Political Writings: James Connolly, London: Jonathan Cape

- Anon. (ed.). 1987. James Connolly: Collected Works (Two volumes). Dublin: New Books

- Ó Cathasaigh, Aindrias (ed.). 1997. The Lost Writings: James Connolly, London: Pluto Press ISBN 0-7453-1296-9

See also

[edit]Biographies

[edit]- Allen, Kieran. 1990. The Politics of James Connolly, London: Pluto Press ISBN 0-7453-0473-7

- Anderson, W.K. 1994. James Connolly and the Irish Left. Dublin: Irish Academic Press. ISBN 0-7165-2522-4.

- Collins, Lorcan. 2012. James Connolly. Dublin: O'Brien Press. ISBN 1-8471-7160-5.

- Cronin, Seán. 2020. James Connolly: Irish Revolutionary. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-3997-0

- Edwards, Ruth Dudley. 1981. James Connolly. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-1112-1

- Fox, R.M. 1946. James Connolly: the Forerunner. Tralee: The Kerryman.

- Greaves, C. Desmond. 1972. The Life and Times of James Connolly (2nd ed.). London: Lawrence and Wishart. ISBN 978-0-85315-234-7

- Levenson, Samuel. 1973. James Connolly, a Biography. London: Martin Brian and O'Keefe. ISBN 978-0-85616-130-8

- Metscher, Priscilla. 2002. James Connolly and the Reconquest of Ireland. Minneapolis: MEP Publications, Univ. of Minnesota. ISBN 0-930656-74-1

- Morgan, Austen. 1990. James Connolly. a Political Biography. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 0-7171-3911-5

- McNulty, Liam. 2022. James Connolly: Socialist, Nationalist and Internationalist. London: Merlin Press. ISBN 0-8503-6783-2.

- Nevin, Donal. 2005. James Connolly: A Full Life. Dublin: Gill & MacMillan. ISBN 0-7171-3911-5.

- O'Callaghan, Sean. 2015. James Connolly: My search for the Man, the Myth and his Legacy. ISBN 9781780894348

- Ransom, Bernard. 1980. Connolly's Marxism, London: Pluto Press. ISBN 0-86104-308-1.

References

[edit]- ^ Ó Cathasaigh, Aindrias. 1996. An Modh Conghaileach: Cuid sóisialachais Shéamais Uí Chonghaile. Dublin: Coiscéim, passim

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Levenson, Samuel (1973). James Connolly: a biography. London: Martin Brian and O'Keeffe. ISBN 978-0-85616-130-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Donal Nevin. 2005. James Connolly: A Full Life, Dublin: Gill and Macmillan; ISBN 0-7171-3911-5

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Greaves, C. Desmond (1972). The Life and Times of James Connolly (2nd ed.). London: Lawrence and Wishart. ISBN 978-0853152347.

- ^ "James Connolly's time as a British soldier, some new evidence". The Treason Felony Blog. 31 July 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ McCabe, Conor (2024). The Lost & Early Writings of James Connolly, 1889 -1898. Dublin: Iskra Books. p. 374. ISBN 9798330435319.

- ^ MacEoin, Uinseann (1980). Survivors: the story of Ireland's struggle as told through some of her outstanding living people ... Dublin: Agenta Publications. p. 184.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Morgan, Austen (1990). James Connolly : a political biography. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-2958-5.

- ^ Johnson, Michael (2016). "How Connolly became a socialist | Workers' Liberty". www.workersliberty.org. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ Young, James D. (1993). "John Leslie, 1856–1921: A Scottish-Irishman As Internationalist". Saothar. 18: 55–61 [55–56]. ISSN 0332-1169. JSTOR 23197307.

- ^ Hadden, Peter (April–May 2006). "The real ideas of James Connolly". Socialism Today. No. 100. London: Socialist Party (England and Wales). Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Metscher, Priscilla (2002). James Connolly and the reconquest of Ireland. Minneapolis: MEP Publications, University of Minnesota. ISBN 0-930656-74-1.

- ^ Connolly, James (January 1897). "Socialism and Nationalism". Shan van Vocht. 1 (1). Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "1916 lives: Passionate words by James Connolly gave hope to many". Irish Examiner. 8 February 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Connolly, James (1 October 1898). "The Language Movement". The Workers’ Republic.

- ^ Stokes, Tom. "Tag Archives: Shan Van Vocht: A Most Seditious Lot: The Feminist Press 1896–1916". The Irish Republic. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Steele, Karen (2007). Women, Press, and Politics During the Irish Revival. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. pp. 39–40, 44–45. ISBN 9780815631170. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ó Faoláin, Seán (1934). Constance Markievicz or The Average Revolutionary. Jonathan Cape.

- ^ Lynch, David (2005), Radical Politics in Modern Ireland – A History of the Irish Socialist Republican Party 1896–1904. Dublin: Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-0716533566

- ^ a b c O'Donnell, L. A. (1987). "Irish Yeast in Trade Unions". Talkin' Union (16).

- ^ Meagher, Meredith (2013). "The girl orator of the Bowery: Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Ireland and the Industrial Workers of the World". History Ireland. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ a b Brundage, David (2016). Irish Nationalists in America: The Politics of Exile, 1798–1998. Oxford University Press. p. 135. ISBN 9780199715824.

- ^ a b c d McCarthy, Conor (2018). "James Connolly, Civil Society and Revolution". Observatoire de la société britannique (23): 11–34. doi:10.4000/osb.2778. ISSN 1775-4135.

- ^ a b c Collins, Lorcan (2013). James Connolly: 16 Lives. The O'Brien Press. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-1-84717-609-7.

- ^ D'Arcy, Fergus (2009). "James Connolly". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ "Census of Ireland 1911". Census.nationalarchives.ie. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ Ryan, William Patrick (1919). The Irish Labor Movement: From the 'twenties to Our Own Day. Talbot Press. pp. 193–194.

- ^ Clarke, Frances (2009). "Galway, Mary | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ a b Woggon, Helga (2000). Silent Radical – Winifred Carney, 1887–1943: A Reconstruction of Her Biography. SIPTU, Irish Labour History Society. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Connolly, James (7 June 1913). "The Awakening of Ulster's Democracy". Forward.

- ^ "Winifred Carney – A Century Of Women". www.acenturyofwomen.com. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ Greiff, Mats (1997). "'Marching Through The Streets Singing And Shouting': Industrial Struggle And Trade Unions Among Female Linen Workers In Belfast And Lurgan, 1872–1910". Saothar. 22: 29–44. ISSN 0332-1169. JSTOR 23198640.

- ^ Callan, Charles (2009). "Labour lives no. 11: Marie Johnson (1874–1974)" (PDF). Soathar. 34: 113–115.

- ^ Morgan, Austen (1991). Labour and Partition: The Belfast Working Class, 1905-1923. London: Pluto Press. pp. 127–139. ISBN 978-0-7453-0326-0.

- ^ a b c d Connolly, James (1911). "Mr. John E. Redmond, M.P.. His Strength and Weakness". Forward (18 March).

- ^ Yeates, Padraig (2013). "The Dublin 1913 Lockout". History Ireland. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ Higgins, Michael D., President of Ireland (2013). "'The Task of Remembering the Lockout of 1913' Address to The Universities Ireland Conference". president.ie. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b O'Callaghan, Sean (2016). James Connolly: My Search for the Man, the Myth and his Legacy. London: Arrow Books. ISBN 9781784751807.

- ^ Watson, Bruce (2005). Bread & Roses: Mills, Migrants, and the Struggle for the American Dream. New York: Penguin Group. pp. 157–161.

- ^ Montefiore, Dora (1913). "Our Fight to Save the Kiddies in Dublin: Smouldering Fires of the Inquisition". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Moriarty, Therese (11 September 2013). "Saving kids, saving souls". The Irish Times. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Morrissey, Thomas J. (2013). "Archbishop Walsh and the 1913 Lock-Out". Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. 102 (407): 283–295. ISSN 0039-3495. JSTOR 23631179.

- ^ "Archbishop attacks 'export of Irish children' | Century Ireland". www.rte.ie. 23 October 1913. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Newsinger, John (1983). "James Connolly and the Easter Rising". Science & Society. 47 (2): 152–177. ISSN 0036-8237. JSTOR 40402480.

- ^ O'Connor, Emmet (2002). "James Larkin in the United States, 1914–23". Journal of Contemporary History. 37 (2): 183–196. doi:10.1177/00220094020370020201. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 3180681.

- ^ a b O'Ceallaigh Ritschel, Nelson (2013). "George Bernard Shaw and the Irish Citizen Army". History Ireland (6).

- ^ Ryan, Alfred Patrick (1956). Mutiny at the Curragh. Macmillan. p. 189. ISBN 978-7-230-01130-3.

- ^ Cardozo, Nancy (1979). Maud Goone: Lucky Eyes and a High Heart. Victor Gollanz. p. 289. ISBN 0-575-02572-7.

- ^ a b Newsinger, John (1985). "'In the Hunger-Cry of the Nation's Poor is Heard the Voice of Ireland': Sean O'Casey and Politics 1908–1916". Journal of Contemporary History. 20 (2): 221–240 [227–228].

- ^ Michael Higgins, President of Ireland (22 March 2016). "Speech at a Reception to Mark the 102nd Anniversary of the Irish Citizen Army". president.ie. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ Finnan, Joseph P. (2004). John Redmond and Irish Unity: 1912–1918. Syracuse University Press. p. 152. ISBN 0815630433. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Michael Tierney, Eoin MacNeill Oxford University Press, 1980, pp. 171–172

- ^ Mac Donncha, Mícheál (2 November 2014). "The Irish Neutrality League". anphoblacht.

- ^ Matgamna, Sean (2023). "James Connolly in World War One: running with the hare and riding with the hounds | Workers' Liberty". www.workersliberty.org. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Connolly, James (1914). "The hope of Ireland". Irish Worker (31 October).

- ^ Yeates, Padraig (2015). The Workers' Republic: James Connolly and the Road to the Rising. SIPTU Communications Department. ISBN 978-0-9555823-9-4.

- ^ Connolly, James (2015). "Conscription". Workers' Republic (27 November).

- ^ Connolly, James (1915). "Trust your Leaders!". Workers' Republic (5 December).

- ^ Workers' Republic, 5 February 1916

- ^ a b c d e Cronin, Seán (2020). James Connolly: Irish Revolutionary. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-3997-0.

- ^ "Remembering the kidnapping of James Connelly". Dublin People. 23 January 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Irish Worker, 10 October 1914

- ^ a b c d Grant, Adrian (2016). "Review of The Life and Times of James Connolly". Saothar. 41: 139–144. ISSN 0332-1169. JSTOR 45283325.

- ^ a b Walshe, Sadhbh (2016), Eight Women of the Easter Rising The New York Times, 16 March.

- ^ "Portraits 1916 Roddy Connolly". RTÉ Archives. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Edwards, Ruth Dudley (1990). Patrick Pearse, The Triumph of Failure. Swords, Co. Dublin: Poolbeg. ISBN 9781853710681.

- ^ Matthews, Ann (2010). Renegades, Irish Republican Women 1900–1922. Dublin: Mercier History. pp. 124–158. ISBN 978-1-85635-684-8.

- ^ a b "EXECUTION OF JAMES CONNOLLY. (Hansard, 30 May 1916)". api.parliament.uk. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ McGreevy, Ronan (18 January 2014). "Only eyewitness account of Easter Rising leaders' burial is made public". The Irish Times. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ Gartland, Fiona (3 May 2016). "1916 court martials [sic] and executions: James Connolly". The Irish Times. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ "James Connolly: Last Statement (1916)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Gone But Not Forgotten – Fiona Connolly". Archived from the original on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Lost memoir tells how James Connolly returned to his faith before execution". Irish Independent. 26 May 2013. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ "Atheist James Connolly turned to God hours before his death according to British Army chaplain". IrishCentral.com. 26 May 2013. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ Golway, Terry (2012). For the Cause of Liberty: A Thousand Years of Ireland's Heroes. Simon and Schuster.

- ^ "The Story of 1916: Chapter 5. The Aftermath of the 1916 Rising". University College Cork. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ Hegarty, Shane; O'Toole, Fintan (24 March 1916). "Easter Rising 1916 – the aftermath: arrests and executions". The Irish Times. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ O'Connor, Emmet (2006). Nevin, Donal (ed.). "Connecting Connolly". Saothar. 31: 85–89. ISSN 0332-1169. JSTOR 23199967.

- ^ a b c d Morgan, Austen (1988). "Connolly and Connollyism: The Making of a Myth". The Irish Review (1986-) (5): 44–55. doi:10.2307/29735380. ISSN 0790-7850. JSTOR 29735380.

- ^ Matgamma, Sean (2023). "Connolly's history and his socialism | Workers' Liberty". www.workersliberty.org. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ McNulty, Liam (2023). "The "legacy" of James Connolly | Workers' Liberty". www.workersliberty.org. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Murphy, Brian (1989). "J. J. O'Kelly, the Catholic Bulletin and Contemporary Irish Cultural Historians". Archivium Hibernicum. 44: (71–88) 82. doi:10.2307/25487490. ISSN 0044-8745. JSTOR 25487490.

- ^ McKenna, Lambert (1991). The Social Teachings of James Connolly. Veritas. ISBN 978-1-85390-133-1.

- ^ a b c d Walsh, Pat (1994). Irish Republicanism and Socialism: The Politics of the Republican Movement 1905–1994. Belfast: Athol Books. ISBN 0850340713.

- ^ a b Hanley, Brian; Millar, Scott (2010). The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-102845-3.

- ^ Lenin, V. I.; Zinoviev, G. Y. (1915). "Socialism and War". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Greaves, E. Desmond (1961). The Life and Times of James Connolly. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

- ^ a b Lyons, Brian (2023). "Land, Labour & the Irish Revolution: 1913-23". Black Dwarf. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ a b Cronin, Seán (1977). "The Rise and Fall of the Socialist Labor Party of North America". Saothar. 3: 21–33. ISSN 0332-1169. JSTOR 23195205.

- ^ a b Connolly, James (1904). "Wages, Marriage and the Church". The People (9 April).

- ^ a b Connolly, James (1908). "Industrial Unionism and Constructive Socialism". Socialism Made Easy. Chicago.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Connolly, James (1917). The Re-conquest of Ireland. Dublin & London: Maunsel & Co.

- ^ McKenna, L. (1919). "The Teachings of James Connolly (Continued)". The Irish Monthly. 47 (556): 532–542. ISSN 2009-2113. JSTOR 20505388.

- ^ a b Greaves, C. Desmond (1984). "Connolly and Easter Week: A Rejoinder to John Newsinger". Science & Society. 48 (2): 220–223. ISSN 0036-8237. JSTOR 40402580.

- ^ Connolly, James (1916). "Notes from the Front: The Ties that Bind". Worker's Republic (5 February).

- ^ a b Connolly, James (1916). "Irish Flag". Workers Republic (8 April).

- ^ Fox, R.M. (1946). James Connolly: The Forerunner. The Kerryman Ltd. pp. 11–12.

- ^ English, Richard (2007), Irish Freedom, the History of Nationalism in Ireland. London: Pan Books, pp. 265- 266. ISBN 978-1405041898

- ^ a b c d e Dillon, Paul (2000). "James Connolly and the Kerry Famine of 1898". Saothar. 25: 29–42. ISSN 0332-1169. JSTOR 23198961.

- ^ Ellis, Peter Beresford (1988). "Introduction. Connolly: His Life and Work". James Connolly: Selected Writings. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-0267-6.

- ^ Connolly, James (1901). "The United Irishmen". Labour in Irish History.

- ^ Mansergh, Nicholas (1975). The Irish Question, 1840-1921: A Commentary on Anglo-Irish Relations and on Social and Political Forces in Ireland in the Age of Reform and Revolution. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-04-901022-2.

- ^ Matgamma, Sean (2023). "Connolly's history and his socialism | Connolly and the landowning peasants". www.workersliberty.org. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Clifford, Brendan (1985). Connolly: The Polish Aspect. Belfast: Athol Books. pp. 94–95.

- ^ Breathnach, Proinnsias (2012) Reluctant co-operators: dairy farmers and the spread of creameries in Ireland 1886-1920. In: At the Anvil: Essays in honour of William J. Smyth. Geography Publications, Dublin, pp. 555-573. ISBN 978-0-906602-63-8

- ^ Allen, Nicholas (2000). "A Revolutionary Cooperation: George Russell and James Connolly". New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua. 4 (3): 46–64. ISSN 1092-3977. JSTOR 20646310.

- ^ Mulholland, M (2018). "Irish Labour and the 'Co-operative Commonwealth' in the era of the First World War". In Bland, Lucy (ed.). Labour, British radicalism and the First World War. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 182–200. ISBN 9781526109293.

- ^ Connolly, James (1898). "The Fighting Race". Workers' Republic (13 August).

- ^ a b Connolly, James (27 May 2011). "Plea For Socialist Unity in Ireland". Forward (Glasgow).

- ^ Walsh, Pat (1994). Irish Republicanism and Socialism: The Politics of the Republican Movement 1905–1994. Belfast: Athol Books. ISBN 0850340713.

- ^ a b Connolly, James (1913). "The Awakening of Ulster's Democracy". Forward (7 June).

- ^ Connolly, James (4 July 1914). "Labour in the new Irish Parliament". Forward (Glasgow).

- ^ Howell, David (1986). A Lost Left: Three Studies in Socialism and Nationalism. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 64. ISBN 9780226355139.

- ^ Mecham, Mike (2019). William Walker, Social Activist & Belfast Labourist (1870–1918). Umiskin Press. pp. 165–167. ISBN 978-1-9164489-6-4.

- ^ Matgamna, Sean (2022). "Connolly and the Protestant workers". workers' Liberty. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ a b Johnson, Michael (2016). "Connolly and the Unionists | Workers' Liberty". www.workersliberty.org. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Connolly, James (1913). "British Labour and Irish Politicians". Forward (3 May).

- ^ Connolly, James (1913). "North East Ulster". Forward (2 August).