Ryukyu independence movement

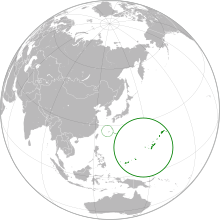

The Ryukyu independence movement (琉球独立運動, Ryūkyū Dokuritsu Undō) is a separatist movement in Japan advocating the independence of the Ryukyu Islands (commonly referred to as Okinawa after the largest island).[1] Some support the restoration of the Ryukyu Kingdom, while others advocate the establishment of a Republic of the Ryukyus (Japanese: 琉球共和国, Kyūjitai: 琉球共和國, Hepburn: Ryūkyū Kyōwakoku).

The current political manifestation of the movement emerged in 1945, after the end of the Pacific War. Some Ryukyuan people felt, as the Allied Occupation (USMGRI 1945–1950) began, that the Ryukyus should eventually become an independent state instead of being returned to Japan. However, the islands were returned to Japan on 15 May 1972 as the Okinawa Prefecture according to the 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement. The US-Japan Security Treaty (ANPO) signed in 1952 provides for the continuation of the American military presence in Japan, and the United States continues to maintain a heavy military presence on Okinawa Island. This set the stage for renewed political activism for Ryukyuan independence. In 2022, public opinion polling in Okinawa put support for independence at 3% of the local population.[2]

The Ryukyu independence movement maintains that both the 1609 invasion by Satsuma Domain and the Meiji construction of the Okinawa prefecture are colonial annexations of the Ryukyu Kingdom. It is highly critical of the abuses of Ryukyuan people and territory, both in the past and in the present day (such as the use of Okinawan land to host American military bases).[3] Advocates for independence also emphasize the environmental and social impacts of the American bases in Okinawa.[4][5]

Historical background

[edit]

The Ryukyuan people are indigenous people who live on the Ryukyu Islands, and are ethnically, culturally, and linguistically distinct from Japanese people. During the Sanzan period, Okinawa was divided into the three polities of Hokuzan, Chūzan and Nanzan. In 1429, Chūzan's chieftain Shō Hashi unified them and founded the autonomous Ryukyu Kingdom (1429–1879), with the capital at Shuri Castle. The kingdom continued to have tributary relations with Ming dynasty and Qing dynasty China, a practice that was started by Chūzan in 1372–1374 and lasted until the downfall of the kingdom in the late 19th century. This tributary relationship was greatly beneficial to the kingdom as the kings received political legitimacy, while the country as a whole gained access to economic, cultural and political opportunities in Southeast Asia without any interference by China in the internal political autonomy of Ryukyu.[6]

In addition to Korea (1392), Thailand (1409) and other Southeast Asian polities, the kingdom maintained trade relations with Japan (1403), and during this period a unique political and cultural identity emerged. However, in 1609 the Japanese feudal domain of Satsuma invaded the kingdom on behalf of the first shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu and Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867) because the Ryukyu king Shō Nei refused to submit to the shogunate. The kingdom was forced to send a tribute to Satsuma, but was allowed to retain and continue its independence and relations and trade with China (a unique privilege, as Japan was prohibited from trading with China at the time). This arrangement was known as a "dual vassalage" status, and continued until the mid-19th century.[7]

During the Meiji period (1868–1912), the Meiji government of the Empire of Japan (1868–1947) began a process later called Ryukyu Shobun ("Ryukyu Disposition") to formally annex the kingdom into the modern Japanese Empire. Firstly established as Ryukyu Domain (1872–1879), in 1879 the kingdom-domain was abolished, established as Okinawa Prefecture, while the last Ryukyu king Shō Tai was forcibly exiled to Tokyo.[8] Previously in 1875, the kingdom was forced against its wishes to terminate its tribute relations with China, while U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant proposed a plan that would maintain an independent, sovereign Okinawa while partitioning other Ryukyuan islands between China and Japan. Japan offered China the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands in exchange for trading rights with China equal to those granted to Western states, de facto abandoning and divided the island chain for monetary profit.[9] The treaty was rejected as the Chinese court decided to not ratify the agreement. The Ryukyu's aristocratic class resisted annexation for almost two decades[10] but after the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), factions pushing for Chinese and Ryukyuan sovereignty faded as China renounced its claims to the island. In the Meiji period, the government continuously and formally suppressed Ryukyuan ethnic identity, culture, tradition, and language while assimilating them as ethnic Japanese (Yamato).[11]

Since the formation of the prefecture, its relationship with the Japanese nation-state has been continually contested and changed. There were significant movements for Okinawan independence in the period following its annexation, in the period prior to and during World War II, and after World War II through to the present day. In 1945, during the WWII Battle of Okinawa, approximately 150,000 civilians were killed, consisting roughly 1/3 of the island's population.[12] Many civilians died in mass suicides forced by the Japanese military.[13] After World War II, the Ryukyu Islands were occupied by the United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands (1945–1950), but the U.S. maintained control even after the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco, and its former direct administration was replaced by the USCAR government. During this period, U.S. military forcibly requisitioned private land for the building of many military facilities, with the private owners put into refugee camps, and its personnel committed thousands of crimes against civilians.[13][14]

Only twenty years later, on 15 May 1972, Okinawa and nearby islands were returned to Japan. As the Japanese had post-war political freedom and economic prosperity, the military facilities had a negative economical impact and the people felt cheated, used for the purpose of Japanese and regional security against the communist threat.[15] Despite Okinawa having been formally returned to Japan, both Japan and the United States have continued to make agreements securing the maintenance and expansion of the U.S. military bases, despite protests from the local Ryukyuan population. Although Okinawa comprises just 0.6% of Japan's total land mass, currently 75% of all U.S. military installations stationed in Japan are assigned to bases in Okinawa.[16][17]

Academic theories of Japanese colonialism

[edit]Some philosophers, like Taira Katsuyasu, consider the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture as outright colonialism. Nomura Koya in his research argued that the Japanese mainland developed "an unconscious colonialism" in which Japanese people are not aware of how they continue to colonize Okinawa through the mainland's inclination to leave the vast majority of the United States' military presence and burden to Okinawa.[18] Eiji Oguma noted that the typical practice of "othering" used in colonial domination produced the perception of a backward "Okinawa" and "Okinawans". Some like Tomiyama Ichiro suggest that for the Ryukyuans, being a member of the modern Japanese nation-state is "nothing other than the start of being on the receiving end of colonial domination".[19]

In 1957, Kiyoshi Inoue argued that the Ryukyu Shobun was an annexation of an independent country over the opposition of its people, thus constituting an act of aggression and not a "natural ethnic unification".[20] Gregory Smits noted that "many other works in Japanese come close to characterizing Ryukyu/Okinawa as Japan's first colony, but never explicitly do so".[21] Alan Christy emphasized that Okinawa must be included in studies of Japanese colonialism.[22]

Historians supporting the interpretation that the annexation of Ryukyu did not constitute colonialism make the following historiographical arguments

- that after the invasion in 1609 the Ryukyu kingdom became part of Tokugawa shogunate's bakuhan system, its autonomy a temporary aberration, and when was established the Okinawa Prefecture in 1879 the islands were already part of the Japanese political influence and it was only an administrative extension i.e. traced the annexation back to 1609 and not 1879.[23]

- the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture was part of the Japanese nation-state integration, reassertion of authority and sovereignty over own territory, and that the Japan's colonial empire, dated from 1895, happened after the state integration and thus it can not be considered as colonial imposition.[24]

- with the creation of "unified racial society" (Nihonjinron) of Yamato people it was created an idea that the Ryukyuan racial incorporation was natural and inevitable. Only recently the scholars like Jun Yonaha begun to see that this idea of unification itself functions as a mean of legitimizing the Ryukyu Shobun.[25]

Some pre-war Okinawans[who?] also resisted the classification of Okinawa as a Japanese colony, as they did not want to consider their experience as colonial. This position originates in the prewar period when the Meiji suppression of Ryukyuan identity, culture and language resulted in self-criticism and inferiority complexes with respect to perceptions that Ryukyuan people were backward, primitive, ethnically and racially inferior, and insufficiently Japanese.[nb 1] They did not want to be lumped together with the Japanese colonies, as evidenced by protests against being included with six other "less developed" colonial people in the "Hall of the Peoples" in the 1903 Osaka Expo.[27][28]

Okinawan historian Higashionna Kanjun in 1909 warned the Ryukyuans that if they forget their historical and cultural heritage then "their native place is no different from a country built on a desert or a new colony".[29] Shimabukuro Genichiro in the 1930s described the Okinawa's pre-war position as "colonial-esque",[29] and in the 1920s he spearheaded a movement[which?] that supported the alteration of personal name spellings to spare Okinawans from ethnic discrimination.[30] The anxiety about the issue of Okinawa being part of Japan was so extreme that even attempts to discuss it were discredited and denounced from both mainland and Okinawan community itself, as a failure of being national subjects.[29]

In Eugen Weber's theorization about the colonies, according to Tze May Loo, the question of Okinawa's status as a colony is a false choice which ignores the complexity of Okinawa's annexation, in which colonial practices were used to establish the Japanese nation-state. He asserts that Okinawa was both a colony and not, both a part of Japan and not, and that this dual status is the basis of the continued subordination of Okinawa. Despite its incorporation as a prefecture and not a colony, colonial policies of "un-forming" and "re-forming" Ryukyuan communities and the Okinawan's proximity to other Japanese colonial subjects were coupled with persistent mainland discrimination and exploitation which reminded them of their unequal status within the Japanese nation-state.[31] They had no choice but to consider their inclusion in the Japanese nation-state as natural in hopes of attaining legitimacy and better treatment. According to Loo, Okinawa is in a vicious circle where Japan does not admit its discrimination against Okinawa, while Okinawans are forced to accept unfair conditions for membership in the country of Japan, becoming an internal colony without end.[32]

Motives

[edit]

During the Meiji period there was a significant reimagining of the histories of Ryukyu and of Ezo, which was annexed at the same time, and an insistence that the non-Japonic Ainu of Hokkaidō and the Japonic Ryukyuan people were Japanese, both racially/ethnically and linguistically/culturally, going back many centuries, despite the evidence they were a significantly different group of people. The primary institution for assimilation was the state education system, which by 1902 occupied over half of the prefectural revenue[clarification needed], and produced a collective identity as well as training Okinawan teachers and intellectuals who would become a front Japanese nationalistic Okinawan elite.[33][34]

Maehira Bokei noted that this narrative considered Okinawa a colony and rejected Okinawa's characteristic culture, considering it barbaric and inferior. This resulted in the development of an inferiority complex amongst Okinawans, which motivated them to discriminate against their own cultural heritage.[35] However, the state did valorize and protect some aspects like being "people of the sea", folk art (pottery, textiles) and architecture, although it defined these cultural elements as being Japonic in essence.[36] The Okinawan's use of heritage as a basis for political identity in the post-war period was interesting to the occupying United States forces who decided to support the pre-1879 culture and claims to autonomy in hopes that their military rule would be embraced by the population.[37][nb 2]

Many Ryukyuan people see themselves as an ethnically separate and different people from the Japanese, with a unique and separate cultural heritage. They see a great difference between themselves and the mainland Japanese people, and many feel a strong connection to Ryukyuan traditional culture and the pre-1609 history of independence. There is strong criticism of the Meiji government's assimilation policies and ideological agenda. According to novelist Tatsuhiro Oshiro, the "Okinawa problem" is a problem of culture which produced uncertainty in the relations between Okinawans and mainland Japanese: Okinawans either want to be Japanese or distinct, mainland Japanese either recognize Okinawans as part of their cultural group or reject them, and Okinawa's culture is treated as both foreign and deserving of repression, as well as being formally considered as part of the same racial polity as Japan.[40]

Ideology

[edit]According to Yasukatsu Matsushima, Professor of Ryukoku University and the representative of the civil group "Yuimarle Ryukyu no Jichi" ("autonomy of Ryukyu"), the 1879 annexation was illegal and cannot be justified on either moral grounds or international law, as the Ryukyu government and people did not agree to join Japan and there is no existing treaty transferring sovereignty to Japan.[41] He notes that the Kingdom of Hawaii was in a similar position, at least the U.S. admitted illegality and issued an apology in 1992, but Japan has never apologized or considered compensation.[9] Japan and the United States are both responsible for the colonial status of Okinawa – used first as a trade negotiator with China, later as a place to fight battles or establish military bases. After the 1972 return to Japan, the government economic plans to narrow the gap between Japanese and Okinawans were opportunistically abused by the Japanese enterprises of construction, tourism, and media which restricted living space on the island, and many Okinawans continue to work as seasonal workers, with low wages while women were overworked and underpaid.[42] Dependent on the development plan, they were threatened with decrease of financial support if they expressed opposition to the military bases (which occurred in 1997 under Governor Masahide Ōta,[43] and in 2014 as a result of Governor Takeshi Onaga's policies[44]). As a consequence of campaigns to improve soil quality on Okinawa, many surrounding coral reefs were destroyed.[45]

According to Matsushima, the Japanese people are not aware of the complexities of the Okinawan situation. The Japanese pretend to understand it and hypocritically sympathize with Okinawans, but until they understand that the U.S. bases as incursions on Japanese soil, and that the lives and land of the Okinawans have the same value as their own, the discrimination will not end. Also, as long Okinawa is part of Japan, the United States military bases will not leave, because it is Japan's intention to use Okinawa as an island military base, seen from the Emperor Hirohito's "Imperial Message" (1947) and US-Japan Security Treaty valid from 1952.[46]

Even further, it is claimed that Okinawa Prefecture's status violates Article 95 of Japanese constitution – a law applicable to one single entity can not be enacted by National Diet without the consent of the majority of the population in the entity (ignored during the implementation of financial plan from 1972, as well in 1996 legal change of law about the stationing of military bases). The constitution's Article 9 (respect for the sovereignty of the people) is violated by the stationing of American military troops, as well as the lack of protection for civilians' human rights. The 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement is deemed illegal – according to international law, the treaty is limited to Okinawa Prefecture as a political entity, while Japan and U.S. also signed a secret treaty according to which the Japanese state cannot act inside the U.S. military bases. Thus, if the reversion treaty is invalid the term "citizens" does not refer to the Japanese, but Okinawans. According to the movement's goals, independence does not mean the revival of the Ryukyu Kingdom, or a reversion to China or Japan, but the establishment of a new and modern Ryukyuan state.[47]

History

[edit]The independence movement was already under investigation by the U.S. Office of Strategic Services's in their 1944 report. They considered it as an organization emerging primarily among Okinawan's emigrants, specifically in Peru, because the territory of Ryukyu and its population were too small to make the movement's success attainable.[48] They noted the long relationship between China and Ryukyu Kingdom, saw the Chinese territorial claims as justified, and concluded that the exploitation of the identity gap between Japan and Ryukyu made for good policy for the United States.[49] George H. Kerr argued that U.S. should not see Ryukyu Islands as Japanese territory. He asserted that the islands were colonized by Japan, and in an echo to Roosevelt's Four Freedoms, concluded that because Matthew C. Perry's visit in 1853 the U.S. treated the Ryukyu as independent kingdom, they should re-examine Perry's suggestion about maintaining Ryukyu as an independent nation with international ports for international commerce.[50]

There was pressure after 1945, immediately following the war during the United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands (1945–1950), for the creation of an autonomous or independent Ryukyu Republic. According to David John Obermiller, the initiative for independence was ironically inspired from mainland. In February 1946, the Japanese Communist Party in its message welcomed a separate administration and supported Okinawa's right to liberty and independence, while the Okinawan organization of leftist leaning intellectuals Okinawajin Renmei Zenkoku Taikai, residing in Japan, also unanimously supported independence from Japan.[51]

In 1947, the three newly formed political parties Okinawa Democratic League-ODL (formed by Genwa Nakasone, conservative), Okinawan People's Party-OPP (formed by Kamejiro Senaga, leftist), and smaller Okinawa Socialist Party-OSP (formed by Ogimi Chotoku) welcomed the U.S. military as an opportunity to free Okinawa from Japan, considering independence from Japan as a republic under guardianship of U.S. or United Nations trusteeship.[52][53] Common people also perceived the U.S. troops as liberators.[54] OPP also considered endorsing autonomy, as well as a request for compensation from Japan,[55] and even during the 1948–1949 crisis, the question of reversion to Japanese rule was not a part political discourse.[51] The governor of the island of Shikiya Koshin, probably with support by Nakasone, commissioned a creation of Ryukyuan flag, which was presented on 25 January 1950.[56] The only notable Ryukyuan who advocated reversion between 1945 and 1950 was the mayor of Shuri, Nakayoshi Ryoko, who permanently left Okinawa in 1945 after receiving no public support for his reversion petition.[51]

In elections in late 1950, the Democratic League (then titled Republican Party) was defeated by the Okinawa Social Mass Party (OSMP), formed by Tokyo University graduates and schoolteachers from Okinawa who were against the U.S. military administration and advocated return to Japan.[57] Media editorials in late 1950 and early 1951, under Senaga's control, criticized the OSMP (pro-reversion) and concluded that U.S. rule would be more prosperous than Japanese rule for Ryukyu.[58] In February 1951, at the Okinawa Prefectural Assembly, the pro-U.S. conservative Republican Party spoke for independence, Okinawa Socialist Party for a U.S. trusteeship, while the OPP (previously pro-independence) and OSMP advocated for reversion to Japan, and in March the Assembly made a resolution for reversion.[59]

"Ethnic pride" played a role in public debate as enthusiasm for independence disappeared, and as the majority were in favor of reversion to Japan, which began to be viewed as the "home country" because of a return to the collective perception of Okinawans as part of the Japanese identity, as promulgated in the 19th century education system and repression, effectively silencing the movement for Okinawan self-determination.[60] According to Moriteru Arasaki (1976), the question of self-determination was too easily and regrettably replaced by the question of preference for U.S. or Japanese dominion, a debate which emphasized Okinawan ethnic connections with the Japanese as opposed to their differences.[55] Throughout the period of formal American rule in Okinawa, there were series of protests (including the Koza riot[61]) against U.S. land policy and against the U.S. military administration.[62] In 1956, one-third of the population advocated for independence, another third for being part of the United States, and final third for maintaining ties with Japan.[63]

Despite the desire of many inhabitants of the islands for some form of independence or anti-reversionism, the massive popularity of reversion supported the Japanese government's decision to establish the Okinawa Reversion Agreement, which put the prefecture back under its control. Some consider the 1960s anti-reversionism was different from the 1950s vision of independence because it did not endorse any political option for another nation-state patronage.[64] Arakawa's position was more intellectual rather than political, which criticized Japanese nationalism (in counterposition to Okinawan subjectivity) and fellow Okinawans' delusions about the prospects of full and fair inclusion in Japanese state and nation, which Arakawa believed would only perpetuate further subjugation.[65] In November 1971, information was leaked that the reversion agreement would ignore the Okinawans' demands and that Japan was collaborating with the United States to maintain a military status quo. A violent general strike was organized in Okinawa, and in February 1972 Molotov cocktails were hurled the Japanese government office building on Okinawa.[66]

Since 1972, because of a lack of any anticipated developments in relation to the US-Japan alliance, committed voices have turned once again towards the aim of "Okinawa independence theory", on the basis of cultural heritage and history, at least by poets and activists like Takara Ben and Shoukichi Kina,[65] and on a theoretical level in academic journals.[67] Between 1980 and 1981 leading Okinawan intellectuals held symposiums about the independence, with even a drafted constitution and another national flag for Ryukyus, with the collected essays published with the title Okinawa Jiritsu he no Chosen (The Challenges Facing Okinawan Independence). The Okinawan branch of NHK and newspaper Ryūkyū Shimpō sponsored a forum for the discussion of reversion, assimilation to the Japanese polity, as well as the costs and opportunities of Ryukyuan independence.[68]

U.S. military bases

[edit]

Though there are pressures in the US and Japan, as well as in Okinawa, for the removal of US troops and military bases from Okinawa, there have thus far been only partial and gradual movements in the direction of removal.

In April 1996, a joint US-Japanese governmental commission announced that it would address Okinawan's anger, reducing the U.S. military foot-print and returning part of the occupied land in the center of Okinawa (only around 5%[citation needed]), including the large Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, located in a densely populated area.[4] According to the agreement, both the Japanese and the U.S. governments agreed that 4,000 hectares of the 7,800-hectare training area are to be returned on condition that six helipads would be relocated to the remaining area. So far, July 2016, only work on two helipads has been completed.[69] In December 2016, U.S. military announced the return of 17% of American-administered areas.[70]

However, while initially considered as a positive change, in September 1996 the public became aware that the U.S. planned to "give up" Futenma for construction of a new base (first since the 1950s) in the north offshore, Oura Bay, near Henoko (relatively less populated than Ginowan) in the municipality of Nago. In December 1996, SACO formally presented its proposal.[71] Although the fighter jet and helicopter noise, as well accidents, would be put away from a very to less populated area, the relocation of Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to Henoko (i.e. Oura Bay) would have a devastating impact on the coral reef area, its waters and ecosystem with rare and endangered species, including the smallest and northernmost population of dugongs on Earth.[71][5]

The villagers organized a movement called "Inochi o Mamorukai" ("Society for the protection of life"), and demanded a special election while maintaining a tent city protest on the beach, and a constant presence on the water in kayaks. The governor's race in 1990 saw the emergence of both an anti-faction and a pro-faction composed of members from construction-based businesses. Masahide Ōta, who opposed the base's construction, won with 52% of the vote. However, the Japanese government successfully sued Ōta and transferred the power over Okinawan land leases to the Prime Minister, ignored the 1997 Nago City citizens' referendum (which had rejected the new base), stopped communication with the local government, and suspended economic support until Okinawans elected the Liberal Democratic Party's Keiichi Inamine as governor (1998–2006).[43]

The construction plans moved slowly, and the protesters got more attention when a U.S. helicopter crashed into a classroom building of Okinawa International University. However, the government portrayed the incident as a further argument for the construction of the new base, and began to harm and/or arrest local villagers and other members of the opposition. By December 2004, several construction workers recklessly wounded non-violent protestors. This caused the arrival of Okinawa fishermen to the Oura Bay.[72]

Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama (16 September 2009 – 2 June 2010) opposed the base facility, but his tenure was short and his campaign promise to close the base was not fulfilled. The subsequent ministers acted as clients for the United States, while in 2013 Shinzō Abe and Barack Obama affirmed their commitment to build the new base, regardless of the local protests.[73] The relocation was approved by Okinawa's governor in 2014,[74] but the governor of the prefecture, Takeshi Onaga (who died in 2018), completely opposed the military base's presence. The 2014 poll showed that 80% of population want the facility out of the prefecture.[75] In September 2015, Governor Onaga went to base his arguments to the United Nations human rights body,[76] but in December 2015, the work resumed as the Supreme Court of Japan ruled against Okinawa's opposition, a decision which erupted new protests.[77] In February 2017, Governor Onaga went to Washington to represent the local opposition to the administration of newly elected U.S. president Donald Trump.[78]

Protests

[edit]Many protests have been staged, but due to the lack of a united political struggle for national independence, these protests have a limited political horizon,[79] although some[who?] consider them to be an extension of the independence and anti-reversionist movement,[65] replacing the previous reversion movement of the 1970s with anti-base and self-determination struggle.[80] Nomura Koya claims that the protests are finally beginning to confront Okinawans with Japanese and American imperialism.[81]

In September 1995, 85,000 people protested because of the U.S. military rape incident.[82][14] This event is considered as the "third wave of the Okinawa Struggle" movement against the marginalization of Okinawa, the US-Japan security alliance, and the U.S. global military strategy.[83] Beside being anti-US, it also had a markedly anti-Japanese tone.[84] In 2007, 110,000 people protested due to Ministry of Education's textbook revisions (see MEXT controversy) of the Japanese military's ordering of mass suicide for civilians during the Battle of Okinawa.[85][86] The journal Ryūkyū Shimpō and scholars Tatsuhiro Oshiro, Nishizato Kiko in their essays considered the U.S. bases in Okinawa a continuation of Ryukyu Shobun to the present day.[87] The Japanese government designation of 28 April, the date on which the Treaty of San Francisco returned sovereignty over Okinawa to Japan, as "Restoration of Sovereignty Day" was opposed by Okinawans, who instead considered it a "day of humiliation".[87][88] In June 2016, after the rape and murder of a Japanese woman, more than 65,000 people gathered in protest of the American military presence and crimes against the residents.[citation needed]

Recent events

[edit]The presence of the U.S. military remains a sensitive issue in local politics. Feelings against the Government of Japan, the Emperor (especially Hirohito due to his involvement in the sacrifice of Okinawa and later military occupation), and the U.S. military (USFJ, SACO) have often caused open criticism, protests, and refusals to sing the national anthem.[89][90] For many years the Emperors avoided visiting Okinawa, since it was assumed that his visits would likely cause uproar, like in July 1975 when then-crown prince Akihito visited Okinawa and communist revolutionary activists threw a Molotov cocktail at him.[91][92][93][94] The first ever visit in history of a Japanese emperor to Okinawa occurred in 1993 by emperor Akihito.[91][95]

The 1995 rape incident stirred a surge of ethnic-nationalism. In 1996, Akira Arakawa wrote Hankokka no Kyoku (Okinawa: Antithesis to the Evil Japanese Nation State) in which argued for resistance to Japan and Okinawa's independence.[96] Between 1997 and 1998 there was a significant increase in debates about Okinawan independence. Intellectuals held heated discussions, symposiums, while two prominent politicians[who?] organized highly visible national forums. In February 1997, a member of the House of Representatives asked the government what was needed for Okinawan independence, and was told that it is impossible because the constitution does not allow it.[65][97] Oyama Chojo, former long-term mayor of Koza/Okinawa City, wrote a best-selling book Okinawa Dokuritsu Sengen (A Declaration of Okinawan Independence), and stated that Japan is not the fatherland of Okinawa.[65][84] The Okinawa Jichiro (Municipal Workers Union) prepared a report about measures for self-government. Some considered the autonomy and independence of Okinawa to be a reaction to Japanese "structural corruption", and made demands for administrative decentralization.[65]

In 2002, scholars of constitutional law, politics and public policy at the University of the Ryukyus and Okinawa International University founded a project "Study Group on Okinawa Self-governance" (Okinawa jichi kenkyu kai or Jichiken), which published a booklet (Okinawa as a self-governing region: What do you think?) and held many seminars. It posited three basic paths; 1) leveraging Article 95 and exploring the possibilities of decentralization 2) seeking formal autonomy with the right to diplomatic relations 3) full independence.[98]

Literary and political journals like Sekai (Japan), Ke-shi Kaji and Uruma neshia (Okinawa) began to frequently write on the issue of autonomy, and numerous books about the topic have been published.[99] In 2005, the Ryūkyū Independent Party, formerly active in the 1970s, was reformed and since 2008 has been known as the Kariyushi Club.[99]

In May 2013, the Association of Comprehensive Studies for Independence of the Lew Chewans (ACSILs) was established, focusing on demilitarization, decolonization, and aim of self-determined independence. They plan to collaborate with polities such as Guam and Taiwan that also seek independence.[99][100] In September 2015, it held a related forum in New York University in New York City.[101]

The topics of self-determination have since entered mainstream electoral politics. The LDP Governor Hirokazu Nakaima (2006–2014), who approved the government's permit for the construction of military base, was defeated in November 2014 election by Takeshi Onaga, who ran on a platform that was anti-Futenma relocation, and pro-Okinawan self-determination. Mikio Shimoji campaigned on the prefecture-wide Henoko-referendum, on the premise that if the result was rejected it would be held as a Scotland-like independence referendum.[102]

In January 2015, The Japan Times reported that the Ryukoku University professor Yasukatsu Matsushima and his civil group "Yuimarle Ryukyu no Jichi" ("autonomy of Ryukyu"), which calls for the independence of the Ryukyu Islands as a self-governing republic,[103] are quietly gathering a momentum. Although critics consider that Japanese government would never approve independence, according to Matsushima, the Japanese approval is not needed because of U.N International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights for self-determination. His group envisions creating an unarmed, neutral country, with each island in the arc from Amami to Yonaguni deciding whether to join.[104]

In February of the same year, Uruma-no-Kai group which promotes the solidarity between Ainu and Okinawans, organized a symposium at Okinawa International University on the right of their self-determination.[98] In the same month an all-day public forum entitled "Seeking a course: Discussions of Okinawa's right to self-determination" was held, asserting that it was the right time to assume its role as a demilitarized autonomous zone, a place of exchange with China and surrounding countries, and a cosmopolitan center for Okinawa's economic self-sufficiency.[105]

View by China

[edit]In July 2012, Chinese Communist Party-owned media Global Times suggested that Beijing would consider challenging Japan's sovereignty over the Ryukyu Islands.[106] The Chinese government has offered no endorsement of such views. Some Chinese consider that it is enough to support their independence, with professor Zhou Yongsheng warning that Ryukyu sovereignty issue will not resolve the Diaoyudao/Senkaku Islands dispute, and that "Chinese involvement would destroy China-Japan relations". Professor June Teufel Dreyer emphasized that "arguing that a tributary relationship at some point in history is the basis for a sovereignty claim ... [as] many countries had tributary relationships with China" could be diplomatically incendiary. Professor Yasukatsu Matsushima expressed his fear of the possibility that Ryukyu independence would be used as a tool, perceiving Chinese support as "strange" since they deny it to their own minorities.[106]

In May 2013, the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, People's Daily, published another similar article by two Chinese scholars from Chinese Academy of Social Sciences which stated that "Chinese people shall support Ryukyu's independence",[107] soon followed by Luo Yuan's comment that "The Ryukyus belong to China, never to Japan".[108] However these scholars' considerations do not necessarily represent the views of Chinese government.[109] It sparked a protest among the Japanese politicians, like Yoshihide Suga who said that Okinawa Prefecture "is unquestionably Japan's territory, historically and internationally".[107][110]

In December 2016, Japan's Public Security Intelligence Agency claimed that the Chinese government is "forming ties with the Okinawan independence movement through academic exchanges, with the intent of sparking a split within Japan".[111] The report was harshly criticized as baseless by the independence group professors asserting that the conference at Beijing University in May 2016 had no such connotations.[112]

In August 2020, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a U.S. think tank, summarized that "China uses indirect methods to influence Japan. There are hidden channels, such as influencing Okinawa's movements through fundraising, influencing Okinawan newspapers to promote Okinawa's independence, and eliminating U.S. forces there." In contrast, the Okinawa Times and Ryukyu Shimpo published articles denying Chinese funding.[113][114][115][116] In light of the Okinawan newspaper articles, Tetsuhide Yamaoka, who supervised the Japanese translation of the Silent Invasion written by Clive Hamilton, gave a lecture titled "Silent Invasion: What Okinawans Want You to Know About China's Gentry Craft" at the Urasoe City Industrial Promotion Center on October 10, 2020, organized by the Japan Okinawa Policy Research Forum. In his lecture, "Silent Invasion: How the CCP is working to make Okinawa Prefecture a dependency of China," Yamaoka stated that the CCP "uses indirect methods that are less visible, such as advertisements, rather than stocks, etc."[117]

In October 2021, the French military school Institute for Strategic Studies (IRSEM) reported that China is stirring up independence movements in the Ryukyu Islands and French New Caledonia in an attempt to weaken potential enemies. It stated that for China, Okinawa is intended to "sabotage the Self-Defense Forces and U.S. forces in Japan."[118][119][120]

There are also some people with official positions who, in their private capacity, openly believe that Japanese rule over the Ryukyus has no legitimacy. For example, Tang Chunfeng, a researcher at the Ministry of Commerce, has claimed that "75% of Ryukyu residents support Ryukyu independence" and that "the culture of the Ryukyu Islands was identical to that of the Mainland China before the Japanese invasion".[121][122] However, despite the increase in the number of voices in China, it is generally agreed that this does not represent the viewpoint of the Chinese government, at least not the official position on the surface. However, these mainly private voices have elicited strong responses from the Japanese political establishment, such as Kan's statement that "Okinawa Prefecture is undoubtedly Japanese territory, both historically and internationally.[107][110] In 2010, the Preparatory Committee for the Chinese Ryukyu Special Autonomous Region was registered in Hong Kong, with businessman Zhao Dong as its president. The organization is active in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, with offices in Shenzhen.[123][124]

The Chinese Ryukyu Special Autonomous Region has also been in contact with Taiwan's Bamboo Union and the Chinese Unification Promotion Party, a political party of the reunification movement. In 2015, CUPP President Chang An-lo visited the organisation's office in Shenzhen, and in the same month, CUPP leader Chang An-lo went on a sightseeing trip to Okinawa and was received by the cadres of the Kyokuryū-kai.[125][126] Chang An-lo said that "the relationship between the Ryukyu and China is historically intertwined, and it is my duty as a Chinese to make Ryukyu free from Japan".[127]

Against this background, the phrase "Today, Hong Kong; tomorrow, Taiwan" was quoted in Hong Kong and Taiwan during the Umbrella Movement,[128] giving rise to the phrase “Today’s Hong Kong is Tomorrow’s Taiwan, and the Day After is Okinawa and Japan"[129] in Japan. Key leaders of the movement are reported to be supported by CCP united front influence operations.[130][131]

On October 3, 2024, Nikkei Asia, in collaboration with a cyber security company, confirmed that there has been an increase in Chinese-language disinformation on social media promoting Ryukyuan independence, which are being spread by some suspected influence accounts. It is believed that the goal is to divide Japanese and international public opinion.[132]

Polls

[edit]Ryukyu independence groups continue to exist, but they have not gained support large enough to lead to independence. The number of seats they were able to take in the local legislatures was either zero or, in rare cases, one. However, there is strong support for a strong local government with strong authority, such as the Dōshūsei and the Federalism such as UK.

In a 2011 poll 4.7% of surveyed were pro-independence, 15% wanted more devolution, while around 60% preferred the political status quo.[133] In a 2015 poll by Ryūkyū Shimpō 8% of the surveyed were pro-independence, 21% wanted more self-determination as a region, while the other 2/3 favored the status quo.[111]

In 2016, Ryūkyū Shimpō conducted another poll from October to November of Okinawans over 20, with useful replies from 1047 individuals: 2.6% favored full independence, 14% favored a federal framework with domestic authority equal to that of the national government in terms of diplomacy and security, 17.9% favored a framework with increased authority to compile budgets and other domestic authorities, while less than half supported status quo.[134]

In 2017, Okinawa Times, Asahi Shimbun (based in Osaka) and Ryukyusu Asahi Broadcasting Corporation (of the All-Nippon News Network), newspapers who are subsidiaries of those in Japan, jointly conducted prefectural public opinion surveys for voters in the prefecture. It claimed that 82% of Okinawa citizens chose "I'm glad that Okinawa has returned as a Japanese prefecture". It was 90% for respondents of the ages of 18 to 29, 86% for those in their 30s, 84% for those aged 40–59, whereas in the generation related to the return movement, the response was 72% for respondents in their 60s, 74% for those over the age of 70.[135]

On May 12, 2022, an Okinawa Times survey on the 50th anniversary of Okinawa's reversion to Japan and the attitudes of Okinawa residents showed that 48% of respondents wanted “a municipality with strong authority,” 42% wanted to “maintain the status quo,” and 3% wanted “independence.”[2]

Identity

[edit]In terms of identity, Okinawans have a composite identity. When asked, "What kind of person do you consider yourself to be?", 52% of the respondents said that they are "Okinawan and Japanese". When combining "Miyako" and "Japanese" as well as "Yaeyama" and "Japanese", the composite identity accounted for about 60% of the respondents. 24% said they were "Okinawan" and 16% said they were "Japanese".[136] Regarding the promotion of culture in Okinawa, there is a view that it should learn from Wales in the United Kingdom regarding federalism and language revival.[137][138] Since Okinawa was a minority in Japan, the history of Welsh Not and Dialect card in Okinawa, etc., are very similar.[139][138] The composite identity is another area where Wales and Okinawa are similar.[140][141][142]

| Both (mixed) | Welsh / Okinawan | British / Japanese | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Welsh-born | 44% | 21% | 7% |

| Okinawan-born | 54.5% | 26.2% | 16.1% |

There are also different views on whether Okinawa should become a state if the Doshu-sei is introduced in the future under the one state on the Doshu-sei in Japan. Author and former diplomat Sato Masaru, whose mother is from Okinawa, describes the uniqueness of Okinawan culture, including the Okinawan language. He favors federalism in Japan but not independence for the Ryukyus, and draws on his experience as a diplomat in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to say, "It is possible for a country of about 1.4 million people to survive as an independent nation among three major powers, Japan, the United States, and China, but I think it will entail many difficulties."[143]

During the Ryukyu Kingdom, the royal family lived in Shuri, Okinawa Island. Yaeyama and Miyakojima were subject to a harsh tax system, known as the poll tax.[144] Therefore, it is believed that Yaeyama, Miyakojima, and Yonaguni Island introduced modern institutions, taxation system, and freedom to choose an occupation after the Meiji Restoration in Japan as a result of the Ryukyu dispositions.[145]

Nakashinjo Makoto, editor-in-chief of the conservative Okinawan newspaper Yaeyama Nippo, said that Shuri Castle was more like a "symbol of oppression" to the islanders of the outlying islands. Therefore, he said, even if a "Ryukyu Republic" is founded, it may become a country full of discrimination like the Ryukyu Kingdom as it was in the past.[146][147]

See also

[edit]- Active autonomist and secessionist movements in Japan

- Amami reversion movement

- Racism in Japan

- Today Hong Kong, Tomorrow Taiwan, Day After Tomorrow Okinawa

Notes

[edit]- ^ Similarly considered in the Office of Strategic Services's report The Okinawas of the Loo Choo Islands: A Japanese Minority Group (1944) and Navy Civil Affairs Team's publication Civil Affairs Handbook: Ryukyu (Loochoo) Islands OPNAV 13–31. First, mostly based on Chinese and American sources, asserted: they were not innately part of Japan, there were notable mostly Chinese and less Korean influences and relations, were oppressed minority group that Japanese people perceived as their rustic cousins, no better than other colonial people, dirty, impolite, uncultured, with an Okinawan commoner stating that "the Okinawans have never felt inferior to the Japanese, rather the Japanese felt the Okinawans were inferior to them", others showing inferiority complex, or superiority complex mostly by former aristocracy or elite. Second, over 95% based on partisan Japanese sources, asserted: with mostly ignored historical aspects, were incorporated as part of Japan, but were innately culturally, socially and racially semi-civilized and inferior people that required structured American guidance in imperialistic sense, subservient to authority, men were lazy, have Ainu racial characteristic (meaning "primitive"), the aboriginal language is backward and so on. Although both represented them as distinctive ethnic minority, the first glorified the idea of U.S. resurrecting formerly independent polity, while the second that the U.S. could succeed, where Japan failed, in civilizing and modernizing the Okinawans by liberating them from themselves.[26]

- ^ The U.S. Office of Strategic Services's 1944 report considered the division between Okinawans and Japanese for the use in the conflict. They noted that probably could not find support among the Okinawans who were educated in Japan because of the nationalist indoctrination, the small Ryukyuan aristocratic class felt pride for not being Japanese and their association with China, the farmers were ignorant of the history and Japan due to lack of education, with the most potential in urban Okinawan population who still remembered and hated the prejudical Japanese behavior.[38] Thus the U.S. during the occupation, instead of the Japanese term Okinawa, promoted the use of the older and Chinese term Ryukyu or Loo Choo, wrongly thinking it is indigenous (it is Uchinaa), and underestimated the Japan's prewar assimilation program with its Japanese identity and negative connotations for the Ryukyu identity.[39]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Dudden 2013, p. 177.

- ^ a b "沖縄が目指すべき姿は「強い権限を持つ自治体」が48% 「現状を維持」が42% 「独立」は3%【復帰50年・県民意識調査】 | 沖縄タイムス+プラス プレミアム | 沖縄タイムス+プラス". 12 May 2022. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ Dudden 2013, p. 177, 181.

- ^ a b Dudden 2013, p. 180.

- ^ a b Dietz 2016, p. 223.

- ^ Loo 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Loo 2014, p. 2.

- ^ Loo 2014, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Matsushima 2010, p. 188.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Loo 2014, pp. 2–3, 12, 25, 32–36.

- ^ Loo 2014, p. 4.

- ^ a b Inoue 2017, pp. XIII–XV.

- ^ a b Tanji 2007, p. 1.

- ^ Inoue 2017, pp. XIII–XIV, 4–5.

- ^ Rabson 2008, p. 2.

- ^ Inoue 2017, p. 2.

- ^ Loo 2014, pp. 6–7, 20.

- ^ Loo 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Loo 2014, p. 7, 20.

- ^ Smits 1999, p. 196.

- ^ Loo 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Loo 2014, p. 7, 11.

- ^ Loo 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Loo 2014, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, pp. 60–90.

- ^ Loo 2014, pp. 8–9, 12–13, 21.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, pp. 70, 82–83.

- ^ a b c Loo 2014, p. 9.

- ^ Yoshiaki 2015, p. 121.

- ^ Loo 2014, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Loo 2014, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, pp. 3, 23–24.

- ^ Loo 2014, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Loo 2014, p. 13.

- ^ Loo 2014, pp. 13–15, 23.

- ^ Loo 2014, p. 15.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Loo 2014, pp. 12, 22.

- ^ Matsushima 2010, p. 187.

- ^ Matsushima 2010, p. 189.

- ^ a b Dietz 2016, pp. 222–223.

- ^ "Tokyo turns up pressure on Okinawa with budget threat". The Japan Times. 21 December 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Matsushima 2010, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Matsushima 2010, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Matsushima 2010, pp. 192–194.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, p. 91.

- ^ a b c Obermiller 2006, p. 213.

- ^ Tanji 2007, p. 56.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, pp. 211–213.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b Tanji 2007, p. 76.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, p. 338.

- ^ Tanji 2007, pp. 57–60.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, p. 302.

- ^ Tanji 2007, p. 61.

- ^ Tanji 2007, p. 72.

- ^ Inoue 2017, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Tanji 2007, p. 5.

- ^ Nakasone 2002, p. 25.

- ^ Tanji 2007, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b c d e f Hook & Siddle 2003.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Tanji 2007, p. 181, 194.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Ayako Mie (22 July 2016). "Okinawa protests erupt as U.S. helipad construction resumes". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Isabel Reynolds; Emi Nobuhiro (21 December 2016). "U.S. Returns Largest Tract of Okinawa Land to Japan in 44 Years". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ a b Dudden 2013, p. 181.

- ^ Dudden 2013, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Dudden 2013, p. 183.

- ^ "Okinawa governor approves plan to reclaim Henoko for U.S. base transfer – AJW by The Asahi Shimbun". Ajw.asahi.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ Isabel Reynolds; Takashi Hirokawa (17 November 2014). "Opponent of U.S. Base Wins Okinawa Vote in Setback for Abe". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ "Onaga takes base argument to U.N. human rights panel". The Japan Times. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 3 October 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ "Protests erupt as work resumes on Futenma air base replacement in Okinawa". The Japan Times. 6 February 2017. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ "Onaga looks to Trump for change in U.S. policy on bases". The Japan Times. 3 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Tanji 2007, p. 18.

- ^ Dietz 2016, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Nakasone 2002, p. 19.

- ^ Inoue 2017, p. 1.

- ^ Tanji 2007, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Obermiller 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Rabson 2008, p. 1.

- ^ Inoue 2017, p. XXVII.

- ^ a b Loo 2014, p. 19.

- ^ Hiroyuki Kachi (28 April 2013). "Sovereignty Anniversary a Day of Celebration, or Humiliation?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ Rabson 2008, p. 11, 17.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, p. 13.

- ^ a b David E. Sanger (25 April 1993). "A Still-Bitter Okinawa Greets the Emperor Coolly". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Rabson 2008, pp. 11–13.

- ^ 知念功 (October 1995). 知念功『ひめゆりの怨念火(いにんび)』インパクト出版会. インパクト出版会. ISBN 9784755400490.

- ^ Rabson 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Obermiller 2006, pp. 14–16.

- ^ a b Dietz 2016, p. 231.

- ^ a b c Dietz 2016, p. 232.

- ^ "The Association of Comprehensive Studies for Independence of the Lew Chewans established". Ryūkyū Shimpō. 13 May 2013. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Sakae Toiyama (29 September 2015). "ACSILs holds forum on Ryukyu independence in New York". Ryūkyū Shimpō. Archived from the original on 3 October 2024. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Dietz 2016, p. 235.

- ^ Loo 2014, p. 20.

- ^ Eiichiro Ishiyama (26 January 2015). "Ryukyu pro-independence group quietly gathering momentum". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Dietz 2016, pp. 232–233.

- ^ a b Kathrin Hille; Mure Dickie (23 July 2012). "Japan's claim to Okinawa disputed by influential Chinese commentators". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ a b c Julian Ryall (10 May 2013). "Japan angered by China's claim to all of Okinawa". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Miles Yu (16 May 2013). "Inside China: China vs. Japan and U.S. on Okinawa". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Jane Perlez (13 June 2013). "Calls Grow in China to Press Claim for Okinawa". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ a b Martin Fackler (5 July 2013). "In Okinawa, Talk of Break From Japan Turns Serious". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ a b Isabel Reynolds (26 December 2016). "Japan Sees Chinese Groups Backing Okinawa Independence Activists". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 29 May 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ "Public Security Intelligence Agency's report claims Ryukyu-China programs aim to divide country". Ryūkyū Shimpō. 18 January 2017. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ "「沖縄独立」に中国暗躍! 外交、偽情報、投資で工作…米有力シンクタンク"衝撃"報告書の中身". 14 August 2020. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "「沖縄の新聞に中国資金」 米シンクタンクのCSIS報告書に誤り 細谷雄一慶応大教授の発言引用". 23 August 2020. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "沖縄タイムス+プラス 沖縄タイムス+プラス ニュース 政治 「中国が沖縄の新聞に資金提供」 報告書の記述撤回 米国シンクタンク「戦略国際問題研究所」". 25 August 2020. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Stewart, Devin (23 July 2020). "China's Influence in Japan: Everywhere Yet Nowhere in Particular CSIS". Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ "【沖縄の声】主催:日本沖縄政策研究フォーラム!山岡鉄秀氏「サイレント・インベージョン~沖縄県民に知ってほしい中国属国化工作の手口~」". YouTube. 14 October 2020. Archived from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "仏軍事研究所が「中国の影響力」報告書 沖縄を標的と指摘 2021/10/5 16:30 三井 美奈 産経新聞". 5 October 2021. Archived from the original on 12 February 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "Foreign influence operations in Japan since the second Abe government Macdonald-Laurier Institute". 26 April 2023. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "OPÉRATIONS D'INFLUENCE CHINOISES". Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "「中国は沖縄独立運動を支持せよ」、「同胞」解放せよと有力紙". Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "中露海軍日本一周の意図:北海道はロシア領、沖縄を中国領に ソ連による終戦後の北方四島侵攻は「米英ソの密約」で行われた 2021.11.9(火)池口 恵観 jbpress". Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "中華民族琉球特別自治区準備委員会のインタビュー動画". YouTube. 20 May 2020. Archived from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "【亞視清盤】又有白武士 內地電子商人趙東願注資六千萬 HK01". 18 April 2016. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "赤ペンキ騒動の党、沖縄の「国連認定」反日組織とも接触 – Reuters". Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "統促黨密會日本黑道 自由時報". Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "幫琉球獨立?白狼:身為中國人的責任三立新聞網". 7 July 2020. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ "Today, Hong Kong; tomorrow, Taiwan:' Resistance to China spreads – Nikkei Asia". Archived from the original on 3 October 2024. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- ^ "Ishigaki on Cutting Edge of Japan's Relationship with Taiwan | JAPAN Forward". 17 March 2021. Archived from the original on 3 October 2024. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- ^ Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany (20 December 2023). "China is winning online allies in Okinawa's independence movement". Axios. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ Hsiao, Russell (26 June 2019). "A Preliminary Survey of CCP Influence Operations in Japan". Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ Kanematsu, Yuichiro (3 October 2024). "Social media fuel pro-Okinawa independence disinformation blitz". Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on 3 October 2024. Retrieved 3 October 2024.

- ^ Justin McCurry (15 September 2014). "Okinawa independence movement seeks inspiration from Scotland". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 October 2024. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ "Ryukyu Shimpo survey reveals 35% of Okinawans favor increased autonomy, less than half support status quo". Ryūkyū Shimpō. 1 January 2017. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ "Was it good to return to Japan? 】 Okinawa 82% is affirmative, as younger generation is higher as a citizen attitude survey". 12 May 2017. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "「沖縄人で日本人」5割 明星大熊本教授の県民調査「自身は何人だと思うか」 複合的アイデンティティー6割に – 琉球新報デジタル|沖縄のニュース速報・情報サイト". 6 June 2023. Archived from the original on 14 June 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "島袋純琉球大学教授に聞く「沖縄史からみた地域政党」". Archived from the original on 3 May 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ a b "VOX POPULI: Rich Okinawan language is in danger of soon becoming extinct". Archived from the original on 3 May 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "「アイム オキナワン」 海外で芽生えた意識、胸張って – 朝日新聞". 10 January 2020. Archived from the original on 5 May 2024. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ a b "The Changing Face of Wales: How Welsh do you feel?". 7 March 2019. Archived from the original on 20 September 2024. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ a b "沖縄における「ナショナル」・アイデンティティ── その担い手と政治意識との関連の実証分析 田辺俊介" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2024. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Global Peace and Goodwill Message translated into Uchinaaguchi for first time". 17 May 2024. Archived from the original on 18 May 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ "佐藤優「翁長さん最大の功績は、日本を見なくなったこと」 <佐藤優×津田大介対談>". 9 January 2019. Archived from the original on 24 January 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "【視点】人頭税の歴史と離島差別 – 八重山日報". 26 November 2019. Archived from the original on 13 January 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "「首里城には怨念を感じる」離島から見た首里の姿に記者苦悩 那覇中心の視点問い直す – 沖縄タイムス". 18 October 2020. Archived from the original on 2 December 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "【沖縄が危ない!】首里城復元、沖縄本島の史観に抵抗感 琉球王国へのノスタルジアばかり強調されるが…離島住民にとっては「圧政の象徴」(1/3ページ) – zakzak:夕刊フジ公式サイト". 14 November 2022. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "【視点】独立論 一足飛びの理想郷はない". 11 May 2022. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Smits, Gregory (1999), Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 9780824820374, archived from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017

- Nakasone, Ronald Y. (2002), Okinawan Diaspora, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2530-0, archived from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017

- Hook, Glen D.; Siddle, Richard (2003), Japan and Okinawa: Structure and Subjectivity, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-42787-1, archived from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017

- Obermiller, David John (2006), The United States Military Occupation of Okinawa: Politicizing and Contesting Okinawan Identity, 1945–1955, ISBN 978-0-542-79592-3

- Tanji, Miyume (2007), Myth, Protest and Struggle in Okinawa, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-21760-1

- Rabson, Steve (February 2008), "Okinawan Perspectives on Japan's Imperial Institution", The Asia-Pacific Journal, 6 (2), archived from the original on 12 August 2020, retrieved 12 February 2017

- Matsushima, Yasukatsu (Autumn 2010), "Okinawa is a Japanese Colony" (PDF), Quarterly for History, Environment, Civilization, 43, translated by Erika Kaneko: 186–195, archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017

- Dudden, Alexis (2013), Jeff Kingston (ed.), Okinawa today: Spotlight on Henoko, Routledge, ISBN 9781135084073, archived from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017

- Loo, Tze May (2014), Heritage Politics: Shuri Castle and Okinawa's Incorporation into Modern Japan, 1879–2000, Lexington Books, ISBN 978-0-7391-8249-9

- Yoshiaki, Yoshimi (2015), Grassroots Fascism: The War Experience of the Japanese People, Columbia University Press, ISBN 9780231538596, archived from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017

- Dietz, Kelly (2016), "Transnationalism and Transition in the Ryūkyūs", in Pedro Iacobelli; Danton Leary; Shinnosuke Takahashi (eds.), Transnational Japan as History: Empire, Migration, and Social Movements, Springer, ISBN 978-1-137-56879-3, archived from the original on 3 October 2024, retrieved 12 February 2017

- Inoue, Masamichi S. (2017), Okinawa and the U.S. Military: Identity Making in the Age of Globalization, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-51114-8

Further reading

[edit]- Matsushima Yasukatsu, 琉球独立への道 : 植民地主義に抗う琉球ナショナリズム [The Road to Ryukyu Independence: A Ryukyuan Nationalism That Defies Colonialism], Kyōto, Hōritsu Bunkasha, 2012. ISBN 9784589033949

External links

[edit] Media related to Ryukyu independence movement at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ryukyu independence movement at Wikimedia Commons