Animal welfare in Nazi Germany

There was widespread support for animal welfare in Nazi Germany[1] (German: Tierschutz im nationalsozialistischen Deutschland) among the country's leadership. Adolf Hitler and his top officials took a variety of measures to ensure animals were protected.[2]

Several Nazis were environmentalists, and species protection and animal welfare were significant issues in the Nazi regime.[3] Heinrich Himmler made an effort to ban the hunting of animals.[4] Hermann Göring was a professed animal lover and conservationist,[5] who threatened to commit Germans who violated Nazi animal welfare laws to concentration camps.[5] In his private diaries, Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels described Hitler as a vegetarian who was contemptuous of Judaism and Christianity for the ethical distinction they drew between the value of humans and the value of animals;[6][5] Goebbels also mentions that Hitler planned to discourage slaughterhouses in the German Reich following the conclusion of World War II.[6] The Nazi government made a law against animal testing but in practice animal testing was permitted and even encouraged in Nazi Germany.[7][8][9]

The current animal welfare laws in Germany were initially introduced by the Nazis.[10]

Measures

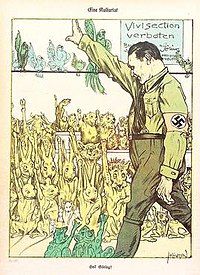

[edit]At the end of the nineteenth century, kosher butchering and vivisection (animal experimentation) were the main concerns of the German animal welfare movement. The Nazis adopted these concerns as part of their political platform.[11] According to Boria Sax, the Nazis rejected anthropocentric reasons for animal protection—animals were to be protected for their own sake.[12] In 1927, a Nazi representative to the Reichstag called for actions against cruelty to animals and kosher butchering.[11]

In 1931, the Nazi Party (then a minority in the Reichstag) proposed a ban on vivisection, but the ban failed to attract support from other political parties. By 1933, after Hitler had ascended to the Chancellery and the Nazis had consolidated control of the Reichstag, the Nazis immediately held a meeting to enact the ban on vivisection. On April 21, 1933, almost immediately after the Nazis came to power, the parliament began to pass laws for the regulation of animal slaughter.[11] On April 21, a law was passed concerning the slaughter of animals; no animals were to be slaughtered without anesthetic.

Göring also banned commercial animal trapping and imposed severe restrictions on hunting. He prohibited boiling of lobsters and crabs. In one incident, he sent a fisherman to a concentration camp for cutting up a bait frog.[13][citation needed]

On November 24, 1933, Nazi Germany enacted another law called Reichstierschutzgesetz (Reich Animal Protection Act), for protection of animals.[14][15] This law listed many prohibitions against the use of animals, including their use for filmmaking and other public events causing pain or damage to health,[16] feeding fowls forcefully and tearing out the thighs of living frogs.[17] The two principals (Ministerialräte) of the German Ministry of the Interior, Clemens Giese and Waldemar Kahler, who were responsible for drafting the legislative text,[15] wrote in their juridical comment from 1939, that by the law the animal was to be "protected for itself" ("um seiner selbst willen geschützt"), and made "an object of protection going far beyond the hitherto existing law" ("Objekt eines weit über die bisherigen Bestimmungen hinausgehenden Schutzes").[18]

On February 23, 1934, a decree was enacted by the Prussian Ministry of Commerce and Employment which introduced education on animal protection laws at primary, secondary and college levels.[19] In 1934, Nazi Germany hosted an international conference on animal welfare in Berlin.[20] On March 27, 1936, an order on the slaughter of living fish and other poikilotherms was enacted. On March 18 the same year, an order was passed on afforestation and on protection of animals in the wild.[19] On September 9, 1937, a decree was published by the Ministry of the Interior which specified guidelines for the transportation of animals.[21] In 1938, the Nazis introduced animal protection as a subject to be taught in public schools and universities in Germany.[20]

On June 28, 1935, Nazi Germany enacted legislation that created a separate category in Paragraph 175 for "fornication with animals" and penalized with up to five years in prison.

Effectiveness

[edit]Although various laws were enacted for animal protection, the extent to which they were enforced has been questioned.

The Nazi government implemented policies to achieve "nutritional freedom" by discouraging the population's consumption of certain foods. The discouraged foods were not restricted to animal products, and some animal products such as quark were actively encouraged, but overall, between 1927 and 1937, these policies resulted in a decline in consumption of 17 percent for meat, 21 percent for milk, and 46 percent for eggs.[22]

Animal experiments in Nazi Germany

[edit]The law

[edit]A law imposing total ban on vivisection was enacted on August 1933, by Hermann Göring as the prime minister of Prussia.[23] He announced an end to the "unbearable torture and suffering in animal experiments" and said that those who "still think they can continue to treat animals as inanimate property" will be sent to concentration camps.[24]

However, the law was revised by a decree 3 weeks later on September 1933, with more lax provisions, allowing the Reich Interior Ministry to distribute permits to some universities and research institutes to conduct animal experiments under conditions of anesthesia and scientific need.[25] Goering stated that it would be the experts who would determine which animal experiments would be conducted and which would be stopped according to their degree of necessity.[26] Furthermore, on November 1933 ,a decree from the minister of the interior excluded animal protection organizations from working in the universities’ animal protection commissions.[23] Eventually, the ministry of the interior sent blank permits to university institutes to conduct experiments on animals and avoided closer supervision of experiments.[25]

In 1936, the Tierärztekammer (Chamber of Veterinarians) in Darmstadt filed a formal complaint against the lack of enforcement of the animal protection laws on those who conducted illegal animal testing, saying that this “may completely paralyze the effect of the law.”[27]

The practice

[edit]In practice animal experimentation flourished in Nazi Germany.[28] The Nazi government not only avoided supervision of animal experiments, but often asked for animal testing and preferred using animals instead of humans when conducting biological experiments. The Weimar Republic passed a law according to which any experiment conducted on humans must first be conducted on animals. Nazi Germany did not repeal this law, and when the Nazi researchers asked to conduct experiments on humans, they stated in their request that they had previously conducted the required experiments on animals.[29] The historian of the holocaust, Raul Hilberg described experiments that the Nazis conducted on animals before they also conducted them on humans.[30]

Anti-tobacco research thrived in Nazi Germany. Cancer research during the Nazi regime was very advanced, and many studies on the harm of smoking were conducted in Germany during this period. Animal experiments have shown that the tar emitted from cigarette smoke can cause cancer. The German experimenters placed rats in cells into which cigarette smoke was introduced. The rats gasped, fell on each other, and finally suffocated to death.[31] In 1938, Nazi researchers succeeded in causing 25% of their laboratory mice to develop lung cancer.[32] Researchers also exposed mice to asbestos to prove that it can cause lung cancer.[33] In 1939, the SS doctor, Sigmund Rascher, performed a series of experiments on animals with the direct cooperation of Himmler. He conducted his experiments mainly in cancer research.[34]

At the University of Freiburg, an experiment was conducted on cats with brain electrode implants.[35] In 1942 the German Nobel laureate bacteriologist Gerhard Domagk conducted infection experiments on animals when he examined the effect of sulfa on gangrene necrosis in animals.[36] The German dermatologist Hans Theodor Schreus also conducted similar infection experiments in animals. In 1941, he infected exposed muscles of mice, then crushed their muscles to encourage the development of infection.[37]

From 1933, the Nazi doctor, Carl Clauberg, conducted experiments on animals in research on reproduction. In his research, he demonstrated how the fertility of animals can be neutralized and then restored.[38] The Nazi neurologist, Georg Schaltenbrand studied multiple sclerosis between 1935-1942. As part of his research, he injected into the spines of great apes fluid from the spines of humans with sclerosis. The monkeys fell ill, but Schaltenbrand was not sure it was multiple sclerosis. In an attempt to find out, he injected the liquid from the monkeys into the spines of 14 mentally and physically disabled people.[39] The German authorities ordered the German chemist, Gerhard Schrader to perform experiments on animals in the field of nerve gas research, and in these experiments, all the animals died. The German army ordered more extensive experiments in nerve gas research on baboons and other types of monkeys. These animals vomited, excreted feces uncontrollably, lost control of their body movements, and convulsed until they died. After these experiments, the German army began to perform identical experiments on prisoners of war who died the same way.[40]

In 1941, the Nazi propaganda film "I Accuse" was released. The purpose of this film, commissioned by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, was to get the public to support euthanasia. In one of the scenes in the film, German researchers (who are trying to find a cure for multiple sclerosis) conduct experiments on mice in an attempt to infect them with the disease. When one of the lab mice drags its hind leg, one of the researchers calls out to his colleagues excitedly, expressing joy at having succeeded in paralyzing the mouse.[41]

As the food supply dwindled, the Nazis began to suffer from a growing shortage of laboratory animals for experimental purposes, and they even considered kidnapping the Gibraltar monkeys for experimental purposes, but this plan was ultimately dropped because it involved high risks.[42] Rabbits raised on a breeding farm for experimental purposes under the management of the German geneticist Hans Nachtsheim were stolen by the residents of Berlin for food purposes near the end of World War II.[42] Nachtsheim used Pentylenetetrazol to induce epilepsy in these rabbits. Before that, he conducted these experiments on children and adults sheltered in psychiatric hospitals, but stopped experimenting on these patients because he thought their psychiatric illness might affect the validity of the scientific results.[40] On June 12, 1944, the head of the Military Academy of Medicine in Berlin, the virologist, Eugen Haagen sent a letter to Brigadier General Walter Schreiber in which he complained that his laboratory mice were running out and asked for a new supply: "May I ask you to endeavor to secure for me several thousand mice of both sexes, preferably only young animals."[43] At the Luftwaffe's animal farm 200,000 rabbits were grown for experimental purposes.[44]

Hunting in Nazi Germany

[edit]Hunting was a common hobby among the leaders of the Nazi regime, Gauleiters, members of the Nazi extermination squads, and extermination camp staff.[45] A non-exhaustive list of hunters among notable Nazis includes: Among Hitler's cabinet ministers: Hermann Göring,[46] Heinrich Himmler,[47][48][49] Joachim von Ribbentrop,[47] Wilhelm Keitel,[50] Hans Frank;[51][52] Among Gauleiters and other senior Nazi politicians: Arthur Greiser,[53] Erich Koch,[48][49] Karl Kaufmann,[45][49] Max Amann;[54] Among SS and Waffen-SS generals: Reinhard Heydrich,[55][56] Oswald Pohl,[57][49] Odilo Globocnik,[49] Gottlob Berger,[58][49] Sepp Dietrich,[59] Werner Lorenz,[60] Karl Wolff,[47][49] Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski,[49] Otto Rasch;[61] Among top army commanders: Erwin Rommel,[62] Heinz Guderian,[63][64] Eduard Dietl,[65] Adolf Galland;[66] Among the Nazi staff in Auschwitz: Rudolf Höss,[67] Richard Baer,[68][69] Eduard Wirths,[70] Horst Schumann,[71] Victor Capesius.[72]

Hermann Göring, was an avid hunter since childhood.[46] He liked to hunt mostly deer and displayed his hunting trophies. He sometimes declared that he wants to shoot "the strongest stag in Europe".[73] For Göring, the hunt and the forest represented the authentic and pure life.[74] In May 1933, Göring was appointed Reich Master of the Hunt (Reichsjägermeister).[75] In this capacity he produced and financed an international hunting exhibition in Berlin in 1937, which Hitler visited on November 6 that year.[76]

In early 1933, Hitler gave Göring a special fund through which he could pursue his passions.[77] With this fund he built his hunting estate: Carinhall, in the Schorfheide Reserve.[77][75] The reserve even appeared in legislation for the protection of nature in a way that coincided with Göring's enjoyment of hunting.[77] Goering held many hunting parties in Carinhall. In the last weeks of the war, he spent his time in Carinhall, and ordered his men to shoot the bisons in the reserve.[78] In the Buchenwald concentration camp, the Nazis established a falconry park and a hunting hall in honor of Göring. There was a game reserve in the place where elk, donkeys, wild boars, mouflon sheep, pheasants, foxes and other animals were kept.[79]

On 3 July 1934, a law Das Reichsjagdgesetz (The Reich Hunting Law) was enacted which limited hunting. The act also created the German Hunting Society with a mission to educate the hunting community in ethical hunting. In July 1, 1935, another law Reichsnaturschutzgesetz (Reich Nature Conservation Act) was passed to protect nature.[15] According to an article published in Kaltio, one of the main Finnish cultural magazines, Nazi Germany was the first state in the world to place the wolf under protection.[80] Nazi Germany "introduced the first legislation for the protection of wolves."[81]

Many of those who devoted their working hours to slaughtering people, preferred to spend their leisure hours hunting animals. Hitler himself said in a conversation on September 7, 1942 that hunting for German officers is like jewelry for women.[82] At a meeting held by Martin Bormann, Hitler's secretary, with the Nazi governors in early 1942, the Gauleiters were so eager to tell their hunting stories that Bormann was unable to conduct a discussion of the serious issues at hand.[45] On July 21, 1941, the SS officer and member of the Einsatzkommando, Felix Landau, noted in his diary: "The men got a day off, and some of them went hunting."[83] At times the hunting of animals could develop into the killing of Jews.[84] The Hocker Album shows images of the Nazi staff of Auschwitz engaging in hunting at their leisure time.[85]

The American conservationist Aldo Leopold visited Germany in 1935 and described that: "Every acre of forestland in Germany, whether state or privately owned, is cropped for game."[86] After the occupation of Poland, its forests became hunting grounds for the Germans.[87]

The Nazi regime encouraged whaling. Under Hitler's rule, Germany became for the first time in its history a nation that engages in whaling on a large scale,[88] and Germany's share of whaling in the Antarctic increased from 2% in 1934 to 19% in 1937.[89] Hitler even claimed in 1942 that the whaling industry could provide more products to the German economy, and that it was important to continue developing it.[90]

Treatment of animals used in the Nazi war effort

[edit]As part of the war effort, Nazi Germany made use of horses, donkeys, mules, oxen and dogs. The Minister of Agriculture, Richard Walther Darré, ordered that all the animals that might be used in the war effort be sent for training so that they would become war animals.[91][92] The Nazis used 200,000 dogs for military purposes (compared to the 6,000 dogs used by the Germans in World War I). Dogs were also used in the concentration camps and extermination camps.[92][93] Using animals in the war effort required massive care and maintenance. Out of 10,000 vets who worked in Germany - 6000 vets were called to serve in the war effort. This massive mobilization prevented sufficient veterinary care for the animals held by the civilian population.[94]

In the Nazi army, dogs were frequently used for tracking, messaging, combat purposes and to guard prisoners. The SS had a special department for corralling and training dogs, and another institute for the production of dog food operated. A prisoner of the Dachau concentration camp testified that "the dogs were part of the family of the SS men". But the care of dogs by the Nazis was not the lot of all dogs. Dogs in the Third Reich, like humans, were divided into two separate basic groups - those who serve the Third Reich and those who are defined as enemies. In occupied Rotterdam for example, when a dog barked at a Nazi patrol, the Nazi officer immediately shot the dog and arrested its owner.[94]

The German army relied heavily on horses for transport purposes in the war, and had 2.75 million horses and mules.[95] In 1945, of Germany's 304 combat units, only 13 were motorized, and the remaining units depended on horses and cattle to carry equipment and heavy weapons.[92][96] The horse losses in the German army were immense.[97] The Germans used a lot of horses but did not take good care of them. The fodder was scarce, the horses suffered from cold and were not properly equipped.[92] Hard work and lack of food caused significant mortality among the horses.[98] Some Nazi officers tortured horses to death.[99][94] According to testimonies of Finnish soldiers: "The Germans did not know how to take care of horses or were too lazy to do so. They had small horses that carried heavy loads on their backs day and night without removing them".[92] In many cases, the horses were slaughtered by the German soldiers for eating purposes.[94]

When the German army was ordered to abandon the Crimean Peninsula on May 8, 1944, Hitler ordered the slaughter of the 30,000 horses of the German army before the troops were abandoned so that they would not fall as booty into the hands of the Russians.[100][101] The Germans lined up the horses and shot them.[94] It was probably the biggest horse massacre in history.[100][101] This massacre, which violated the laws for the protection of animals and was also not necessary from a military point of view, was an expression of the scorched earth policy introduced by the Nazi regime.[94] The RAF parachuted baskets with 20,000 pigeons in German occupied countries for the purpose of transmitting information back to Britain. The Nazis, who were aware of this use of pigeons, killed thousands of these pigeons in the air.[102]

During the war, German soldiers sometimes engaged in wild looting of cattle and chicken from the local populations.[103] The 18th Panzer Division reported many cases of senseless animal slaughter by the German soldiers. The German soldiers burned houses, destroyed agricultural equipment, killed the local animals and poisoned water wells by throwing animal carcasses into the contents.[104]

At the beginning During WW2 the Zoos and traveling menageries in Germany received orders to shoot all the beasts of prey in them, probably as an air-raid precaution and as part of the austerity measure the war necessitates. Most of them complied.[105] During the war the German army destroyed several Zoos in Poland. They bombed Warsaw Zoo two days before the surrender of Poland in 1939, killings many of the animals there.[106][107] The surviving animals were transported to Germany, but those deemed redundant were shot. The Poznań Old Zoo was also bombed killing many animals there.[106][108]

Treatment of "Jewish" Animals

[edit]Even before the outbreak of World War II, at the time of the pogroms of Kristallnacht in 1938, the Nazi mob had abused not only the Jews but also their pets. Thus we find descriptions of how Jews and their dogs were thrown from windows into their deaths.[109]

More formally, on May 15, 1942, the Nazis issued an order instructing all Jews to bring all their pets to collection points where they will be euthanized. Alternatively, the order allowed the Jews to have their pets killed by a veterinary, and to give the authorities a certificate from the veterinary. The order forbade Jews to save their pets by giving them to non-Jews.[110][111][112]

In the Łódź Ghetto, all the Jews who owned dogs were required to bring them for a rabies test on July 22, 1940, and all the dogs tested on the same day were exterminated on the pretext of preventing rabies. From then on, ghetto Jews were forbidden to hold dogs.[113] In the Kovno Ghetto, the dogs and cats were gathered in one of the synagogues where they were shot, and their bodies were left to rot for several months in order to degrade the synagogue and prevent its use.[114]

Controversies

[edit]Policies regarding non-Nazi activists

[edit]Scholars who argue that the Nazis were not authentic supporters of animal rights point out that the Nazi regime disbanded some organizations advocating environmentalism or animal protection. However these organizations, such as the 100,000-member strong Friends of Nature, were disbanded because they advocated political ideologies that were illegal under Nazi law.[115] For example, the Friends of Nature was officially non-partisan, but activists from the major rival party, the Social Democratic Party, were prominent among its leaders.[116]

See also

[edit]- Ecofascism

- Savitri Devi

- Anti-tobacco movement in Nazi Germany

- Animal welfare and rights in Germany

- Holocaust analogy in animal rights

References

[edit]- ^ DeGregori, Thomas R (2002). Bountiful Harvest: Technology, Food Safety, and the Environment. Cato Institute. p. 153. ISBN 1-930865-31-7.

- ^ Arnold Arluke; Clinton Sanders (1996). Regarding Animals. Temple University Press. p. 132. ISBN 1-56639-441-4.

- ^ Robert Proctor (1999). The Nazi War on Cancer. Princeton University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-691-07051-2.

- ^ Martin Kitchen (2006). A History of Modern Germany, 1800-2000. Blackwell Publishing. p. 278. ISBN 1-4051-0040-0.

- ^ a b c St. Clair, Jeffrey; Cockburn, Alexander (4 March 2016). "Feeling Their Pain: Animal Rights and the Nazis". Counterpunch. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ a b Goebbels, Joseph; Louis P. Lochner (trans.) (1993). The Goebbels Diaries. Charter Books. p. 679. ISBN 0-441-29550-9.

- ^ C. Ray Greek, Jean Swingle Greek (2002). Sacred Cows and Golden Geese: The Human Cost of Experiments on Animals. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 90. ISBN 0-8264-1402-8.

- ^ Frank Uekötter (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 0-521-84819-9.

- ^ Frank Uekötter (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-521-84819-9.

- ^ Bruce Braun, Noel Castree (1998). Remaking Reality: Nature at the Millenium. Routledge. p. 92. ISBN 0-415-14493-0.

- ^ a b c d Arnold Arluke, Clinton Sanders (1996). Regarding Animals. Temple University Press. p. 133. ISBN 1-56639-441-4.

- ^ Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 42. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- ^ Kathleen Marquardt (1993). Animalscam: The Beastly Abuse of Human Rights. Regnery Publishing. p. 125. ISBN 0-89526-498-6.

- ^ Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 179. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- ^ a b c Luc Ferry (1995). The New Ecological Order. University of Chicago Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-226-24483-0.

- ^ Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 175. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- ^ Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 176. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- ^ Clemens Giese and Waldemar Kahler (1939). Das deutsche Tierschutzrecht, Bestimmungen zum Schutz der Tiere, Berlin, cited from: Edeltraud Klüting. Die gesetzlichen Regelungen der nationalsozialistischen Reichsregierung für den Tierschutz, den Naturschutz und den Umweltschutz, in: Joachim Radkau, Frank Uekötter (ed., 2003). Naturschutz und Nationalsozialismus, Campus Verlag ISBN 3-593-37354-8, p.77 (in German)

- ^ a b Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 181. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- ^ a b Arnold Arluke, Clinton Sanders (1996). Regarding Animals. Temple University Press. p. 137. ISBN 1-56639-441-4.

- ^ Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 182. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- ^ Collingham, Lizzie (2012). The Taste of War. New York: Penguin Press. pp. 29, 347, 353–357. ISBN 9781594203299.

- ^ a b Frank Uekötter (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-521-84819-9.

- ^ Arnold Arluke, Clinton Sanders (1996). Regarding Animals. Temple University Press. p. 133. ISBN 1-56639-441-4.

- ^ a b Frank Uekötter (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 0-521-84819-9.

- ^ Arluke, Arnold; Sax, Boria (1992). "Understanding Nazi Animal Protection and the Holocaust". Anthrozoös. 5: 6–31. doi:10.2752/089279392787011638.

- ^ Frank Uekötter (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-521-84819-9.

- ^ C Ray Greek, M. D., and Jean Swingle Greek. Sacred cows and golden geese: The human cost of experiments on animals. Continuum publishing, 2001. p. 90

- ^ Weindling, Paul (2014). Victims and Survivors of Nazi Human Experiments: Science and Suffering in the Holocaust. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-4411-8930-1.

- ^ Arnold Arluke, Clinton Sanders (1996). Regarding Animals. Temple University Press. p. 135. ISBN 1-56639-441-4.

- ^ Proctor, Robert. Nazi Science and Nazi Medical Ethics: Some Myths and Misconceptions. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, Volume 43, Number 3, Spring 2000, pp. 338.

- ^ Proctor, Robert (2018). The Nazi War on Cancer. Princeton University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-691-18781-5.

- ^ Proctor, Robert (2018). The Nazi War on Cancer. Princeton University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-691-18781-5.

- ^ Angelika Ebbinghaus. The Nuremberg Medical Trial 1946/1947. Guide to the Microfiche Edition. De Gruyter; Reprint edition. 2001. p. 129

- ^ Uekötter, Frank. The green and the brown: A history of conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press, 2006. pp. 56-57

- ^ Rubenfeld, Sheldon; Benedict, Susan (2014). Human Subjects Research after the Holocaust. Springer. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-3-319-05702-6.

- ^ Rubenfeld, Sheldon; Benedict, Susan (2014). Human Subjects Research after the Holocaust. Springer. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-3-319-05702-6.

- ^ Weindling, Paul (2014). Victims and Survivors of Nazi Human Experiments: Science and Suffering in the Holocaust. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4411-8930-1.

- ^ Weindling, Paul (2014). Victims and Survivors of Nazi Human Experiments: Science and Suffering in the Holocaust. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-1-4411-8930-1.

- ^ a b Sax, Boria (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. A&C Black. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8264-1289-8.

- ^ Ich klage an, directed by Wolfgang Liebeneiner, 1941. Minute 43:40

- ^ a b Rubenfeld, Sheldon; Benedict, Susan (2014). Human Subjects Research after the Holocaust. Springer. p. 145. ISBN 978-3-319-05702-6.

- ^ "Nuremberg - Transcript Viewer - Transcript for NMT 1: Medical Case". Harvard Law Faculty. p. 740. Retrieved 2024-11-25.

- ^ "Nuremberg - Transcript Viewer - Transcript for NMT 1: Medical Case". Harvard Law Faculty. p. 7937. Retrieved 2024-11-25.

- ^ a b c Uekötter, Frank (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-521-61277-7.

- ^ a b Uekötter, Frank (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-521-61277-7.

- ^ a b c Felix Kersten. The Kersten Memoirs: 1940-1945. 1956. p. 112: In one day at Ribbentrop's hunting lodge, "Ribbentrop shot 410 pheasants. Himmler only 91. Karl Wolff 16".

- ^ a b Longerich, Peter (2012). Heinrich Himmler: A Life. Oxford University Press. p. 554. ISBN 978-0-19-959232-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ingrao, Christian (2013). The SS Dirlewanger Brigade: The History of the Black Hunters. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-62087-631-2.

- ^ Keitel, Wilhelm (2000). The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Wilhelm Keitel. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 13, 189. ISBN 978-0-8154-1072-0.

- ^ Housden, M. (2003). Hans Frank: Lebensraum and the Holocaust. Springer. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-230-50309-0.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Dean, Martin (2012). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933 –1945: Volume II: Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Indiana University Press. p. 739. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- ^ Epstein, Catherine (2012). Model Nazi: Arthur Greiser and the Occupation of Western Poland. Oxford University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-19-964653-1.

- ^ Hale, Oron James (2015). The Captive Press in the Third Reich. Princeton University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4008-6839-1.

- ^ ARTHUR NEBE (1950-02-08). "DAS SPIEL IST AUS". Der Spiegel . ISSN 2195-1349.

- ^ Felix Kersten. The Kersten Memoirs: 1940-1945. 1956. p. 92: "Heydrich much enjoys shooting. Less from any love of the open air or the excitement of the chase, than because he must make a kill".

- ^ Wachsmann, Nikolaus (2015). KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 390. ISBN 978-1-4299-4372-7.

- ^ Weale, Adrian (2012). The SS : a new history. Abacus. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-349-11752-2.

- ^ Taylor, Blaine (2017). Guarding The Führer: Sepp Dietrich and Adolf Hitler. Fonthill Media. p. 212.

- ^ Lumans, Valdis O. (1993). Himmler's Auxiliaries: The Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle and the German National Minorities of Europe, 1933-1945. University of North Carolina Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8078-2066-7.

- ^ Musmanno, Michael Angelo (1961). The Eichmann kommandos. Internet Archive. Macrae Smith. p. 242.

- ^ Butler, Daniel Allen (2015). Field Marshal: The Life and Death of Erwin Rommel. Casemate. p. 466. ISBN 978-1-61200-297-2.

- ^ Macksey, Kenneth (2018). Panzer General: Heinz Guderian and the Blitzkrieg Victories of WWII. Skyhorse. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-5107-2732-8.

- ^ Stahel, David (2023). Hitler's Panzer Generals: Guderian, Hoepner, Reinhardt and Schmidt Unguarded. Cambridge University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-009-28278-9.

- ^ Baur, Hans (2013). I Was Hitler's Pilot: The Memoirs of Hans Baur. Grub Street Publishers. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-78346-982-6.

- ^ Blood, Philip W. (2021). Birds of Prey. Columbia University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-3-8382-1567-9.

- ^ Langbein, Hermann (2004). People in Auschwitz. University of North Carolina Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-8078-2816-8.

- ^ Höss, Rudolf (1992). Death Dealer: The Memoirs of the SS Kommandant at Auschwitz. Prometheus Books. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-87975-714-4.

- ^ "SS officers gather for drinks in a hunting lodge". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 1944. Retrieved 2024-06-14.

- ^ Lifton, Robert Jay (1986). The Nazi doctors : medical killing and the psychology of genocide. Basic Books. p. 403. ISBN 978-0-465-04904-2.

- ^ Lifton, Robert Jay (1986). The Nazi doctors : medical killing and the psychology of genocide. Basic Books. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-465-04904-2.

- ^ Posner, Patricia (2017). The Pharmacist of Auschwitz: The Untold Story. Crux Publishing Ltd. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-909979-40-6.

- ^ Uekötter, Frank (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-521-61277-7.

- ^ Bookbinder, Paul (1992). “NAZI ANIMAL PROTECTION AND THE JEWS: A RESPONSE". In: Arluke, Arnold; Boria Sax. "Understanding Nazi animal protection and the Holocaust." Anthrozoös 5.1

- ^ a b Manvell, Roger (2011). Goering : the rise and fall of the notorious Nazi leader. Frontline Books. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-61608-109-6.

- ^ Hitler, Adolf; Domarus, Max (1990). Speeches and Proclamations, 1932-1945: The years 1935 to 1938. Tauris. p. 974. ISBN 978-1-85043-163-3.

- ^ a b c Uekötter, Frank (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-0-521-61277-7.

- ^ Uekötter, Frank (2006). The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-521-61277-7.

- ^ Kogon, Eugen (2006). The theory and practice of hell : the German concentration camps and the system behind them. New York : Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-374-52992-5.

- ^ Aikio, Aslak (February 2003). "Animal Rights in the Third Reich". Archived from the original on September 6, 2006. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ Sax, Boria (2001). The Mythical Zoo: an Encyclopedia of Animals in World Myth, Legend, and Literature. ABC-CLIO. p. 272. ISBN 1-5760-7612-1.

- ^ Trevor-Roper, Hugh. Hitler's Table Talk 1941-1944: Secret Conversations. Enigma Books. 2000. p. 451. ISBN 978-1-936274-93-2.

- ^ Klee, Ernst; Dressen, Willi; Riess, Volker (1991). "The Good Old Days": The Holocaust as Seen by Its Perpetrators and Bystanders. Konecky Konecky. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-56852-133-6.

- ^ Westermann, Edward B. (2018). "Drinking Rituals, Masculinity, and Mass Murder in Nazi Germany". Central European History. 51 (3): 389. doi:10.1017/S0008938918000663. ISSN 0008-9389. JSTOR 26567845.

- ^ "Auschwitz Through the Lens of the SS: The Album". The US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2024-06-20.

- ^ Blood, Philip W. (2021). Birds of Prey. Columbia University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-3-8382-1567-9.

- ^ Brüggemeier, Franz-Josef; Cioc, Mark; Zeller, Thomas (2005). How Green Were the Nazis?: Nature, Environment, and Nation in the Third Reich. Ohio University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8214-1647-1.

- ^ David Edgerton. Not Counting Chemistry: How We Misread the History of 20th-Century Science and Technology. Science History Institute. 2008-05-20

- ^ Charlotte Epstein, The Power of Words in International Relations: Birth of an Anti-Whaling Discourse, MIT Press, 2008-10-03, p. 47-49, ISBN 978-0-262-26267-5

- ^ Trevor-Roper, Hugh. Hitler's Table Talk 1941-1944: Secret Conversations. Enigma Books. 2000. p. 468. ISBN 978-1-936274-93-2.

- ^ Campbell, Clare (2013). "Wolves Not Welcome". Bonzo's war : animals under fire 1939-1945. London : Corsair. ISBN 978-1-4721-0679-7.

- ^ a b c d e "Animals and War: Studies of Europe and North America", Animals and War, Brill, 2012-11-01, ISBN 978-90-04-24174-9, retrieved 2024-08-12

- ^ Kistler, John M. Animals in the Military: From Hannibal's Elephants to the Dolphins of the US Navy. ABC-CLIO, 2011. p. 24

- ^ a b c d e f Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- ^ Mitcham Jr, Samuel W. (2007) Retreat to the Reich: the German defeat in France, 1944. Stackpole books. p. 223

- ^ World War II: A Student Companion (Student Companions to American History) by William L. O'Neill. Oxford University Press, 1999. p. 125

- ^ Walter S. Dunn Jr. (1995). Utilization of Horses. The Soviet Economy and the Red Army, 1930-1945. Praeger.

- ^ Bartov, Omer. (1992) Hitler's army: Soldiers, Nazis, and war in the Third Reich. Oxford University Press. p. 17

- ^ Kistler, John M. (2011) Animals in the Military: From Hannibal's Elephants to the Dolphins of the US Navy. ABC-CLIO. p. 207

- ^ a b Arluke, Arnold (2010). Regarding Animals. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-4399-0388-9.

- ^ a b Arluke, Arnold, and Boria Sax. "Understanding Nazi animal protection and the Holocaust." Anthrozoös 5.1 (1992): 6-31.

- ^ Cooper, Jilly (2010-12-23). Animals In War. Random House. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-4090-3190-1.

- ^ Bratton, Susan Power. "Luc Ferry's critique of deep ecology, Nazi nature protection laws, and environmental anti-semitism." Ethics and the Environment 4.1 (1999): 3-22.

- ^ Bartov, Omer (1991). Soldiers, Nazis, and war in the Third Reich. Oxford University Press. p. 82

- ^ Chapter 8: Wolves Not Welcome. in Campbell, Clare. Bonzo's War: Animals Under Fire 1939-1945. Hachette UK, 2013.

- ^ a b Johnson, Clelly, "PRISONERS IN WAR: ZOOS AND ZOO ANIMALS DURING HUMAN CONFLICT 1870-1947" (2015). All Theses. 2222.

- ^ Fox, F. (2001). Endangered species: Jews and buffaloes, victims of Nazi Pseudo‐science. East European Jewish Affairs, 31(2), 82–93.

- ^ Kisling, Vernon N. (2000). Zoo and Aquarium History: Ancient Animal Collections To Zoological Gardens. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-3924-5.

- ^ Landau, Ronnie S. (1994). The Nazi Holocaust. Ivan R. Dee. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-4616-9943-9.

- ^ Stoltzfus, Nathan (2001). Resistance of the Heart: Intermarriage and the Rosenstrasse Protest in Nazi Germany. Rutgers University Press. pp. 174–175. ISBN 978-0-8135-2909-7.

- ^ Klemperer, Victor (2016). I Will Bear Witness, Volume 2: A Diary of the Nazi Years: 1942-1945. Random House Publishing Group. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-399-58908-9.

- ^ Anton Gill (1988), The Journey Back from Hell, An Oral History: Conversations with Concentration Camp Survivors. William Morrow, p. 408

- ^ "A German police order of Aug. 14". The Center for Jewish History Archives. 1940-08-14. Retrieved 2024-11-07.

- ^ Tory, Avraham (1990). Surviving the Holocaust: The Kovno Ghetto Diary. Harvard University Press. pp. 67, 310. ISBN 978-0-674-85811-4.

- ^ Boria Sax (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 41. ISBN 0-8264-1289-0.

- ^ William T Markham (2008). Environmental Organisations in Modern Germany: Hardy Survivors in the Twentieth Century and Beyond. Regnery Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-0857450302. Archived from the original on 2020-08-25. Retrieved 2020-05-23.