Michael Musmanno

Michael Musmanno | |

|---|---|

From a 1960 court photograph | |

| Born | Michael Angelo Musmanno April 7, 1897 |

| Died | October 12, 1968 (aged 71) Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, US |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Education | George Washington University (BA, MA) Georgetown University (LLB) |

| Occupation(s) | jurist, politician, naval officer and author |

| Political party | Republican (before 1932) Democratic (after 1932) |

Michael Angelo Musmanno (April 7, 1897 – October 12, 1968) was an American jurist, politician, and naval officer. Coming from an immigrant family, he started to work as a coal loader at the age of 14. After serving in the United States Army in World War I, he obtained a law degree from Georgetown University. For nearly two decades from the early 1930s, he served as a judge in courts of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Entering the U.S. Navy during World War II, he served in the military justice system.

Following the war, in 1946, Musmanno served as military governor of an occupied district in Italy. Beginning in 1947, he served as a presiding judge for the Einsatzgruppen trial in U.S. military court at Nuremberg. In 1948, he conducted interviews with several people who had worked closely with Adolf Hitler. In 1950, he published a book based on his research, in which he argued that Hitler had indeed committed suicide in Berlin in 1945.

In 1951, Musmanno was elected as a justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, where he served until his death in 1968. He set a record for the number of dissenting opinions filed. In addition to his long judicial career and postwar contributions in Europe, he wrote sixteen books and many articles related to his court cases and professional career. In his writing he expressed sympathy for working men and deep interest in the Italians in the United States, himself having Italian ancestry.

Viewed as a "maverick on the court",[1] Musmanno was known for defending Sacco and Vanzetti, as well as for being anti-Communist, and for supporting civil rights.[2] In 1966, in response to new evidence of the Norse colonization of North America (c. 1000), he published a book in which he argued that Christopher Columbus was the first European to discover the Americas. He died on Columbus Day 1968. At the time of his death, he was regarded as "one of Pennsylvania's most respected and colorful figures".[3]

Early life and education

[edit]Musmanno was born in Stowe Township, in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, an industrial neighborhood a few miles west of Pittsburgh, into an ethnic Italian family originally from Noepoli, Basilicata.[4] He worked with his father in the coal mines, began law school at Georgetown University in 1915, leaving to serve as an infantryman in World War I[5] before returning to earn an LL.B. degree in 1918 at Georgetown. Afterwards he earned B.A. and M.A. degrees at George Washington University, and two master of law degrees at the National University School of Law (later merged with George Washington University Law School). He became a labor lawyer and always kept a sympathy for the working man.[6]

Career

[edit]Politics and judiciary

[edit]After entering law practice in 1923 as a lawyer in his native Stowe Township, Musmanno got also involved in politics. In 1926, he ran for election to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives on the Republican ticket, but lost. As he was genuinely interested in the plight of the working man, and was sympathetic to the Italian Americans and other ethnic minorities who worked in great numbers in Pennsylvania industries, Musmanno volunteered to serve as an appellate attorney during the Sacco-Vanzetti case and moved to Boston. The men had been convicted and sentenced to death in 1921, in an atmosphere of anti-immigrant feeling. The appeals upheld the lower court decision, and Sacco and Vanzetti were executed in 1927. Haunted by the conduct of the trial, Musmanno wrote After Twelve Years (1939),[7] a book about the case, as well as two articles in 1963, published in The New Republic and the Kansas Law Review.

After returning, Musmanno was elected in 1928 as a Republican state legislator for Pennsylvania serving in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives.[6][8] He was reelected in 1930.

When miner John Barkoski was beaten to death in Imperial, Pennsylvania in 1929 by the Coal and Iron Police during a strike, Musmanno was outraged and, as a state legislator, introduced a bill to banish this private police force.[6] The bill was vetoed by a Republican Pennsylvania governor, which led to Musmanno's resignation.[9] He published a short story about the case, entitled "Jan Volkanik." This was adapted in part as the basis of the film Black Fury (1935), starring Paul Muni as a coal miner, and with a screenplay written by Abem Finkel and Carl Erickson. It was directed by Michael Curtiz.

In 1931, Musmanno became the youngest judge in the county court of Allegheny County; he was nominated by both Democrats and Republicans and endorsed by the labor organizations. He switched to the Democratic Party in 1932 while canvassing for Franklin D. Roosevelt as a president.[citation needed] In 1933, he served as a judge of the Court of Common Pleas of Allegheny County.[9]

In 1943 he took a leave from his judicial duties to take part in World War II.[9] After returning to Pittsburgh in 1948, he was appointed as a judge in the common pleas court, where he served until 1951.[6]

World War II

[edit]In 1943, during World War II, Musmanno entered the United States Navy as a line officer assigned as a military attorney, since the navy had not yet formed its own Judge Advocate General's Corps (an action not taken until 1967). In this capacity, he eventually rose to the rank of rear admiral. He served as Allied Military Governor of the Sorrentine Peninsula in Italy.[10]

In 1946, he was appointed head of the three-person Board of Soviet Repatriation of Displaced Persons in Austria. He opposed the forcible repatriation to the Soviet Union of Cossacks and refugees, many of whom did not want to be repatriated. He was successful in aiding some of these people. Later it was learned that Stalin's government persecuted many of these returnees, condemning many to internal exile or the harsh labor camps of the gulag in Siberia, where they died.

Beginning in 1947, Musmanno was presiding judge at the Einsatzgruppen trial of the U.S. Nuremberg Military Tribunal, held in Nuremberg for men charged with killing more than a million people behind the front lines, including Jews, Poles, and minorities.[11] He also served as a member of the court during the military trials of Milch and Pohl. In 1961, Musmanno testified as a prosecution witness in Jerusalem in the Israeli trial of Adolf Eichmann.

In 1948, Musmanno conducted interviews with several people who had worked closely with Adolf Hitler in the very last days of World War II, in an attempt to disprove claims of Hitler's escape despite his presumed suicide at the end of the Battle of Berlin.[12] These interviews, conducted with the help of a simultaneous interpreter named Elisabeth Billig,[13] served as the basis of a 1948 article Musmanno wrote for The Pittsburgh Press, as well as his 1950 book, Ten Days to Die. In both, he cites as evidence that Hitler could not have survived: the death of his "right-hand man" Joseph Goebbels,[a] the testimony of several eyewitnesses who saw Hitler dead (allegedly by a gunshot through the mouth, but accounts later changed)[16][17] and Nazis who claimed Hitler used no doubles during his lifetime (despite an apparent Hitler body double being found near the Führerbunker), as well as a "jawbone" identified by Hitler's dental assistants[18][19] (which was revealed in a 1968 Soviet book to have been sundered around the alveolar process).[20][17] Musmanno's argument that Hitler's body was never found because it was burnt to near-ashes has been echoed by main-line historians, such as Anton Joachimsthaler,[16][21] and Ian Kershaw.[22] British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, who also investigated Hitler's death, argued (in agreement with later scientific analyses)[23] that bones survive even indoor cremations.[24] Trevor-Roper stated in 1966 that he was "disinclined to believe anything that is stated by that flatulent ass Musmanno".[25] In his 2019 book, British historian Luke Daly-Groves defends Trevor-Roper's criticism as being somewhat just, while pointing out that evidence was limited in 1950, and ultimately praising Musmanno's refutations of Hitler's purported survival.[26]

Additionally, Musmanno wrote a screenplay about Hitler's fate, which he hoped Alfred Hitchcock would direct.[12] In 1980, Musmanno's relatives donated his archives to Duquesne University; in 2007, the school digitized the footage of the interviews for a 2010 German TV documentary, with an American version airing in 2015.[12][27]

Post-war career

[edit]Musmanno tried to re-enter politics, running unsuccessfully for Lieutenant Governor in 1950. He resumed his judicial career.

A strong anti-Communist in the postwar years, Musmanno was an unofficial spokesman for the local Americans Battling Communism. He was noted for testifying for the prosecution in the 1950 anti-Communist sedition case against Steve Nelson, who was leading a regional branch of the American Communist Party.[28] The Communists had sold political tracts (available at any library[29]) for $5.75 to Musmanno, who declared their store "the equivalent of an advance post of the Red Army."[30] Nelson initially was sentenced to 20-years in prison, $10,000 in fines and $13,000 in prosecution costs. The Supreme Court of the United States ultimately threw out the case and the Pennsylvania and other state anti-sedition laws, saying federal law superseded the state law under which Nelson was prosecuted.[30][31]

Perhaps the most blatant example of Musmanno's misconduct came when he launched into a tirade against an attorney appearing before him in a civil case. Musmanno demanded that the attorney state whether he was a communist, and when the attorney declined to answer, Musmanno held him in contempt and forbade the attorney from practicing in his court. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court reversed Musmanno's order and described Musmanno's methods as "detestable." Schlesinger Petition, 367 Pa 476, 483 (Pa. 1951).

Musmanno gained name recognition from his part in the Nelson trial. He was elected in 1951 as justice to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania,[29] serving from 1952 to his death in 1968. During his long career on the bench, he "became known as an advocate for the underdog."

He also was noted for his dissenting opinions; during his first 5 years on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, he wrote more dissenting opinions than all of the other justices on the court had collectively written in the previous 50 years.[32] When asked if he read Musmanno's dissenting opinions, Pennsylvania Chief Justice Horace Stern said he was not "interested in current fiction."[33] Not long afterward, however, the court issued a ruling in which this Justice participated, and the wording was unquestionably similar to that in one of Musmanno's dissenting opinions.[34] In Perpetua v. Philadelphia Transportation Company, Musmanno wrote the dissenting opinion, while in Koehler v. Schwartz, he wrote the prevailing opinion, in which Stern joined him.[34] In a book about personal injury suits and these cases, the attorney Melvin Belli added that Chief Justice Stern "lived to regret" his insulting remark.[34]

In one case, because Musmanno had failed to circulate a dissenting opinion among the other justices before he filed it, the piece was not published in the official Pennsylvania State Reports. He sought a writ of mandamus to require its publication. The trial court denied the writ. When the Pennsylvania Supreme Court heard the case, Musmanno represented himself as plaintiff; the Court affirmed the lower court's decision.[35]

While a controversial figure for such actions, Musmanno was noted as having wonderful "pro-labor credentials."[29] In addition, during the 1960s he supported civil rights marchers.[29]

Musmanno appeared as himself on the February 12, 1962 episode of To Tell the Truth. He received all four votes.[36]

Musmanno strongly dissented from a 1966 ruling that Henry Miller's book Tropic of Cancer was not obscene. He wrote:

"Cancer" is not a book. It is a cesspool, an open sewer, a pit of putrefaction, a slimy gathering of all that is rotten in the debris of human depravity. And in the center of all this waste and stench, besmearing himself with its foulest defilement, splashes, leaps, cavorts and wallows a bifurcated specimen that responds to the name of Henry Miller. One wonders how the human species could have produced so lecherous, disgusting and amoral a human being as Henry Miller. One wonders why he is received in polite society.[37]

Books

[edit]Musmanno was a gifted narrator[38] and wrote a total of sixteen books, some reflecting his court cases. He described the sedition case in his book, Across the Street from the Courthouse (1954). Other works include a 30-page transcript of his 1932 debate with Clarence Darrow on immortality in Pittsburgh, The Story of Italians in America (1965), and Glory & The Dream: Abraham Lincoln, Before and After Gettysburg (1967). In 1966 he published a novel version of the 1935 film, Black Fury, by the same name.

Musmanno was very proud of his Italian heritage. In 1966, he authored the book Columbus Was First (stylized as Columbus WAS First), arguing that Christopher Columbus was the first European to discover the New World.[39] This was in reaction to the archaeological discovery of L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland and connected scholarly research showing that Vikings had reached the northeast coast of North America almost 500 years before Columbus' time.[40] Musmanno doubted that the earlier exploration had occurred on the basis that the alleged Vinland Map was a falsification.[39] Subsequent scholars agree that the map is a forgery,[41][42] but L'Anse aux Meadows is a confirmed Norse site scientifically dated to the early 11th century.[43][44][45]

The judge was a lifelong Catholic and attended the Mount St. Peter Church in New Kensington. On 11 November 1951, he was the first lay orator to read from the pulpit of the newly dedicated building.[46]

Musmanno was intensely religious. The last of his many dissenting opinions was against overturning an assault/attempted rape conviction in a case in which the trial judge instructed the jury to seek God's guidance in reaching their decision. He wrote in his dissent:

I was afraid it would come to this. It is becoming the fashion to make light of religious invocation. Books are being published asking whether God is dead. Well, God is not dead, and judges who criticize the invocation of Divine Assistance had better begin preparing a brief to use when they stand themselves at the Eternal Bar of Justice on Judgment Day.[47]

Justice Musmanno concluded:

"I am perfectly willing to take my chances with [the trial judge] at the gates of Saint Peter and answer on our 'voir dire' that we were always willing to invoke the name of the Lord in seeking counsel in rendering a grave decision on earth, which I believe the one in this case to be."

– Miserere nobis Omnipotens Deus![47]

Justice Musmanno died the following day, October 12, 1968, Columbus Day.[2]

Legacy and honors

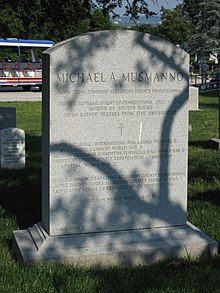

[edit]- Musmanno is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[48]

- His former home in Stowe Township has been designated a state historic landmark.

- 1993, a historical marker was placed in his honor near his residence in McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania.[6]

Articles and books

[edit]Catalogue entries of his writings are available at Hathi Trust Digital Library.[49]

- The Library for American Studies in Italy, [Rome], 1925.

- Proposed Amendments to the Constitution (monograph), U.S. Government Printing Office, 1929.

- After Twelve Years (about Sacco–Vanzetti case), Knopf, 1939.

- The General and the Man (biography of Mark W. Clark), Mondadori, 1946.

- Listen to the River (novel), Droemersche Verlagsanstalt, 1948.

- War in Italy (autobiographical), Valecchi, 1948.

- Ten Days to Die, Doubleday, 1950 (about Hitler's death).

- Across the Street from the Courthouse, Dorrance, 1954.

- Justice Musmanno Dissents (compilation), foreword by Roscoe Pound, Bobbs–Merrill, 1956.

- Verdict!: The Adventures of the Young Lawyer in the Brown Suit, Doubleday, 1958.

- The Eichmann Kommandos, Macrae, 1961 (about the Einsatzgruppen trial), full text online.

- The Death Sentence in the Case of Adolf Eichmann: A Letter to His Excellency Itzhak Ben-Zvi, President of the State of Israel, Jerusalem, [Pittsburgh], 1962.

- "Man with an Unspotted Conscience: Adolf Eichmann's Role in the Nazi Mania Is Weighed in Hannah Arendt's New Book" (pamphlet), [New York], 1963.

- "Was Sacco Guilty?", [New York]: The New Republic, March 1963.

- "The Sacco–Vanzetti Case," Kansas Law Review, [Lawrence, KS], May 1963.

- The Story of the Italians in America, Doubleday, 1965.

- Black Fury (novel), Fountainhead, 1966.

- Columbus Was First, Fountainhead, 1966.

- That's My Opinion, Michie Company, 1967.

- The Glory and the Dream: Abraham Lincoln, Before and After Gettysburg, Long House, 1967.

- Michael Angelo Musmanno - Il giudice di Pittsburgh, USA - Cittadino onorario di Minturno (1945), Pier Giacomo Sottoriva, Arti grafiche Caramanica (Collana personaggi della memoria minturnese), 2021. Michael Angelo Musmanno - The judge of Pittsburgh, USA - Honorary citizen of Minturno (1945), Pier Giacomo Sottoriva, Caramanica Graphic Arts (Series of characters from Minturno memory), 2021.

References

[edit]Footnotes

- ^ Just before Hitler killed himself, Goebbels and his wife implored him not to do so, in part to save their children to spare them a fate of falling into Soviet hands or death. Hitler gave Goebbels permission to leave with his family, but he refused to abandon his post.[14][15]

Citations

- ^ Justice Musmanno, Reading Eagle, October 16, 1968

- ^ a b Chris Potter, You Had to Ask: "I heard that Duquesne University's library has a Michael Musmanno room...", Pittsburgh City Paper, 12 May 2005, accessed 12 September 2013

- ^ Musmanno is Buried at Arlington, Gettysburg Times, October 18, 1968

- ^ "I lucani di successo in Usa" (in Italian). December 2, 2019. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ fn 3 supra

- ^ a b c d e "Michael Musmanno Historical Marker", Explore Pennsylvania History

- ^ Michael Musmanno. After Twelve Years. New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1939.

- ^ Harold Cox-Wilkes University

- ^ a b c LaGumina, Salvatore J. The Italian American Experience: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Pub, 2000.

- ^ LaGumina, Salvatore J. The Humble and the Heroic: Wartime Italian Americans. Youngstown, NY: Cambria Press, 2006, p. 227.

- ^ See: Earl, Hilary C. The Nuremberg SS–Einsatzgruppen Trial, 1945–1958: Atrocity, Law, and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.[ISBN missing]

- ^ a b c Ove, Torsten (November 14, 2015). "Documenting Hitler's dying day". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "Guide to the Elisabeth Billig Papers". library.osu.edu. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Eberle, Henrik; Uhl, Matthias, eds. (2005). The Hitler Book: The Secret Dossier Prepared for Stalin from the Interrogations of Hitler's Personal Aides. Translated by Giles MacDonogh. New York: Public Affairs. pp. 269–270. ISBN 978-1-58648-366-1.

- ^ Bradsher, Greg (November 27, 2015). "Hunting Hitler Part IV: The Bunker (Afternoon, April 30)". The Text Message. Retrieved November 18, 2024 – via the National Archives.

- ^ a b Joachimsthaler, Anton (2000) [1995]. The Last Days of Hitler: The Legends, The Evidence, The Truth. Translated by Helmut Bölger. London: Cassell. pp. 166, 252–53. ISBN 978-1-85409-465-0.

- ^ a b Charlier, Philippe; Weil, Raphael; Rainsard, P.; Poupon, Joël; Brisard, J.C. (May 1, 2018). "The remains of Adolf Hitler: A biomedical analysis and definitive identification". European Journal of Internal Medicine. 54: e10 – e12. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2018.05.014. PMID 29779904. S2CID 29159362.

- ^ Musmanno, Michael (July 23, 1948). "Roundup of Facts and Evidence Proves Conclusively Death was Hitler's Fate". The Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh, PN. p. 21. Retrieved November 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Musmanno, Michael A. (1950). Ten Days to Die. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. pp. 231–32, 234, 236, 238–39, 242–43.

- ^ Bezymenski, Lev (1968). The Death of Adolf Hitler (1st ed.). New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. p. 45.

- ^ Daly-Groves 2019, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 955–958.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Benecke, Mark (December 12, 2022) [2003]. "The Hunt for Hitler's Teeth". Bizarre. Retrieved March 4, 2024 – via Dr. Mark Benecke.

- Thompson, Tim; Gowland, Rebecca. "What Happens to Human Bodies When They Are Burned?". Durham University. Retrieved May 9, 2024 – via FutureLearn.

- Castillo, Rafael Fernández; Ubelaker, Douglas H.; Acosta, José Antonio Lorente; Cañadas de la Fuente, Guillermo A. (March 10, 2013). "Effects of temperature on bone tissue. Histological study of the changes in the bone matrix". Forensic Science International. 226 (1): 33–37. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.11.012. hdl:10481/91826. ISSN 0379-0738.

- ^ Trevor-Roper, Hugh (2002) [1947]. The Last Days of Hitler (7th ed.). London: Pan Macmillan. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-330-49060-3.

- ^ Daly-Groves 2019, pp. 11, 17.

- ^ Daly-Groves 2019, p. 17.

- ^ Mandak, Joe (November 12, 2015). "Film of Hitler confidants set for Smithsonian Channel debut". AP News. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ Korea gunfire started raid on reds here, Musmanno tells court, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 17, 1951

- ^ a b c d Philip Jenkins. The Cold War at Home: The Red Scare in Pennsylvania, 1945–1960 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 1999. Quote: "Party leaders were facing long prison terms ... Musmanno was [elected to] the state supreme court."

- ^ a b Pennsylvania v. Nelson, 350 U.S. 497 (1956).

- ^ Chris Potter, You Had to Ask: "I recently read an obituary of John McTernan...", Pittsburgh City Paper, 18 August 2005, 12 September 2013

- ^ Jesse Dukeminier & Stanley M. Johanson, Wills, Trusts, and Estates 211 n.25 (4th ed. 1990).

- ^ New Republic, 3 February 1968, p. 14

- ^ a b c Melvin Belli, Blood Money: Ready for the Plaintiff! New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1956, pp. 285–287

- ^ Musmanno v. Eldredge, 382 Pa. 167, 114 A.2d 511 (1955). From Google Scholar. Retrieved on June 10, 2012

- ^ "To Tell the Truth". CBS. June 7, 2016. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ Commonwealth v. Robin, 421 Pa. 70, 91, 218 A.2d 546, 556 (1966). From Google Scholar. Retrieved on June 10, 2012.

- ^ Guberman, Ross. Point Taken: How to Write Like the World's Best Judges. New York, Oxford University Press, 2015.[ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Tuttle, Cliff (1994). "Christopher Columbus' American Lawyer: Michael A. Musmanno and the Vinland Map" (PDF). Pittsburgh History. Retrieved February 7, 2022 – via The Pennsylvania State University.

- ^ Fuoco, Michael A. (February 29, 2000). "Continuing Vinland Map feud might make Musmanno smile". Post-Gazette. The New York Times (contributor). Pittsburgh, PA. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ Freedman, Paul (November 28, 2011). "HIST-210: Lecture 22 - Vikings / The European Prospect". Open Yale courses. Archived from the original on August 27, 2014. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- ^ Yuhas, Alan (September 30, 2021). "Yale Says Its Vinland Map, Once Called a Medieval Treasure, Is Fake". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Bird, Lindsay (May 30, 2018). "Archeological quest for Codroy Valley Vikings comes up short – Report filed with province states no Norse activity found at dig site". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Kuitems, Margot; Wallace, Birgitta L.; Lindsay, Charles; Scifo, Andrea; Doeve, Petra; Jenkins, Kevin; Lindauer, Susanne; Erdil, Pınar; Ledger, Paul M.; Forbes, Véronique; Vermeeren, Caroline (October 20, 2021). "Evidence for European presence in the Americas in AD 1021". Nature. 601 (7893): 388–391. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03972-8. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 8770119. PMID 34671168. S2CID 239051036.

- ^ Cordell, Linda S.; Lightfoot, Kent; McManamon, Francis; Milner, George (2009). "L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site". Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-313-02189-3.

- ^ Centennial Committee (2004). Mt. St. Peter Church Centennial – 100 years of faith, Pittsburgh, Pa: Broudy Printing Inc., p. 76.

- ^ a b Commonwealth v. Holton, 432 Pa. 11, 41, 247 A.2d 228, 242 (1968). From Google Scholar. Retrieved on June 10, 2012.

- ^ Burial Detail: Musmanno, Michael A (Section 2, Grave 4735-E) – ANC Explorer

- ^ Author: "Mussmano, Michael Angelo", Hathi Trust Digital Library, accessed 12 September 2013

Sources

[edit]- Daly-Groves, Luke (2019). Hitler's Death: The Case Against Conspiracy. Oxford, UK: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-4728-3454-6.

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Paul B. Beers, Pennsylvania Politics: Today and Yesterday: The Tolerable Accommodation, University Park: Penn State Press, 1980.

External links

[edit]- Michael Angelo Musmanno at ArlingtonCemetery.net, an unofficial website

- "Judge Michael Musmanno", Pittsburgh Post Gazette

- Len Barcousky, "Eyewitness 1937: Pittsburgh papers relished 'Musmanntics'", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 7 March 2010

- The Musmanno Papers Archived February 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Duquesne University

- Musmanno's role in the Nuremberg Trials Archived May 28, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Holocaust History website

- "Michael Angelo Musmanno", Pittsburgh City Paper

- 1897 births

- 1968 deaths

- People from Stowe Township, Pennsylvania

- Republican Party members of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives

- Justices of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania

- United States Navy admirals

- Politicians from Pittsburgh

- Writers from Pittsburgh

- Judges of the United States Nuremberg Military Tribunals

- Pennsylvania district justices

- 20th-century American judges

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- American anti-fascists

- American anti-communists

- American people of Italian descent

- 20th-century members of the Pennsylvania General Assembly