Raft

A raft is any flat structure for support or transportation over water.[1] It is usually of basic design, characterized by the absence of a hull. Rafts are usually kept afloat by using any combination of buoyant materials such as wood, sealed barrels, or inflated air chambers (such as pontoons), and are typically not propelled by an engine. Rafts are an ancient mode of transport; naturally-occurring rafts such as entwined vegetation and pieces of wood have been used to traverse water since the dawn of humanity.

Human-made rafts

[edit]

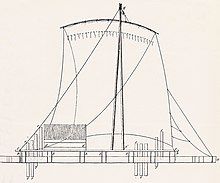

Traditional or primitive rafts were constructed of wood, bamboo or reeds; early buoyed or float rafts use inflated animal skins or sealed clay pots which are lashed together.[2]: 15, 17, 43 Modern float rafts may also use pontoons, drums, or extruded polystyrene blocks. Depending on its use and size, it may have a superstructure, masts, or rudders.

Timber rafting is used by the logging industry for the transportation of logs, by tying them together into rafts and drifting or pulling them down a river.[citation needed] This method was very common up until the middle of the 20th century but is now[when?] used only rarely.

Large rafts made of balsa logs and using sails for navigation were important in maritime trade on the Pacific Ocean coast of South America from pre-Columbian times until the 19th century. Voyages were made to locations as far away as Mexico, and many trans-Pacific voyages using replicas of ancient rafts have been undertaken to demonstrate possible contacts between South America and Polynesia.[3]

Rafts used for recreational rafting are almost exclusively inflatable rafts, manufactured of flexible materials such as PVC, hypalon, polyurethane, and nylon[4]. These materials are resistant to the collisions and heavy wear the boats experience when traveling through whitewater[4]. Whitewater rafts are also designed with high rocker, an raised bow and stern which allows them to pass over waves and obstacles more easily[5]. Most have drain holes in the floor to prevent the boat from becoming swamped with water.

Natural rafts

[edit]In biology, particularly in island biogeography, non-manmade rafts are an important concept. Such rafts consist of matted clumps of vegetation that has been swept off the dry land by a storm, tsunami, tide, earthquake or similar event; in modern times[when?] they sometimes also incorporate other kind of flotsam and jetsam, e.g. plastic containers. They stay afloat by its natural buoyancy and can travel for hundreds, even thousands of miles and are ultimately destroyed by wave action and decomposition, or make landfall.[citation needed]

Rafting events are important means of oceanic dispersal for non-flying animals. For amphibians, reptiles, and small mammals, in particular, but for many invertebrates as well, such rafts of vegetation were often the only means by which they could reach and – if they were lucky – colonize oceanic islands before human-built vehicles provided another mode of transport.[citation needed]

Image gallery

[edit]-

Three Arks for a log drive on Pine Creek, in Lycoming or Tioga County, Pennsylvania. The left ark was for cooking and dining, the middle ark was the sleeping quarters and the right ark was for the horses. The arks were built for just one log drive and then sold for their lumber. The line of the Jersey Shore, Pine Creek and Buffalo Railway can be seen on the eastern shore: the mountainside behind it is nearly bare of trees from clearcutting.[6]

-

Raft carrying visitors to Tom Sawyer Island at Disneyland, about 1960

-

People on the raft in Estonia, 1944

-

Raft used to ferry vehicles at Citarum River, Karawang, West Java, Indonesia

-

Rafting on the Dunajec River at Pieniny, about 2005–2010

-

A woman using a raft to transport her daughter and goats

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ G. & C. Merriam Co., Websters New Collegiate Dictionary, 1976, ISBN 0-87779-339-5

- ^ McGrail, Sean (2014). Early ships and seafaring : water transport beyond Europe. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books Limited. ISBN 9781473825598.

- ^ Smith, Cameron M. and Haslett, John F. (1999), "Construction and Sailing Characteristics of a Pre-Columbian Raft Replica", Bulletin of Primitive Technology, pp. 13–18

- ^ a b Kayakish. "Understanding the different materials used in Inflatable Boats and their durability". Kayakish. Retrieved 2024-12-02.

- ^ Aaron (2020-09-06). "Raft Materials and Designs". Best Rafting and Kayaking Expeditions. Retrieved 2024-12-02.

- ^ Thomas T. Taber, III, Williamsport Lumber Capital, 1995, p. 13

![Three Arks for a log drive on Pine Creek, in Lycoming or Tioga County, Pennsylvania. The left ark was for cooking and dining, the middle ark was the sleeping quarters and the right ark was for the horses. The arks were built for just one log drive and then sold for their lumber. The line of the Jersey Shore, Pine Creek and Buffalo Railway can be seen on the eastern shore: the mountainside behind it is nearly bare of trees from clearcutting.[6]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a6/Pine_Creek_Arks.jpg/200px-Pine_Creek_Arks.jpg?auto=webp)