Racial identity of Sakanoue no Tamuramaro

Since the 20th century, some scholars have suggested that Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, a Japanese military officer during the Heian period who made a great contribution to the Emishi conquest as a sei-i taishōgun (Dainagon), was of African descent. Specifically, the claim was that he was black. The theory is recorded in North America as early as 1911. Although this theory has failed to provide any convincing evidence, it has continued to be cited into the 21st century, primarily by black scholars, and has been considered proof of the presence of African people in ancient Japan.[1]

General story

[edit]It is recorded in the entry for June, 785 (4th year of Enryaku) in the Shoku Nihongi.

Tamuramaro's father, Sakanoue no Karitamaro, said that their ancestor, Achi no omi of the Yamatonoaya clan, was the great-grandson of Emperor Ling of the Later Han Dynasty , and that he had come from Daifang County with his companions after hearing that there was a sage in an eastern country (Japan).[2]

The group was called "七姓民" because they had a total of seven Chinese surname.

右衞士督從三位兼下総守坂上大忌寸苅田麻呂等上表言。臣等本是後漢靈帝之曾孫阿智王之後也。漢祚遷魏。阿智王因牛教。出行帶方。忽得寳帶瑞。其像似宮城。爰建國邑。育其人庶。後召父兄告曰。吾聞。東國有聖主。何不歸從乎。若久居此處。恐取覆滅。即携母弟迂興徳。及七姓民。歸化來朝。是則譽田天皇治天下之御世也。於是阿智王奏請曰。臣舊居在於帶方。人民男女皆有才藝。近者寓於百濟高麗之間。心懷猶豫未知去就。伏願天恩遣使追召之。乃勅遣臣八腹氏。分頭發遣。其人民男女。擧落隨使盡來。永爲公民。積年累代。以至于今。今在諸國漢人亦是其後也。臣苅田麻呂等。失先祖之王族。蒙下人之卑姓。望 。改忌寸蒙賜宿祢姓。伏願。天恩矜察。儻垂聖聽。所謂寒灰更煖。枯樹復榮也。臣苅田麻呂等。不勝至望之誠。輙奉表以聞。詔許之。坂上。内藏。平田。大藏。文。調。文部。谷。民。佐太。山口等忌寸十一姓十六人賜姓宿祢。 - 『続日本紀』延暦四年六月条

Achi no omi's naturalization from China is recorded in several documents such as "Nihon Shoki," "Shoku Nihongi," and "Shinsen Shōjiroku," but there is no record that he called himself a descendant of Emperor Ling of Han from the beginning.[3]

Development and reception of the theory

[edit]Pre-World War II

[edit]

In 1911, Canadian anthropologist Alexander Francis Chamberlain wrote about Sakanoue no Tamuramaro in his book, "The Contribution of the Negro to Human Civilization," when introducing several black people who have contributed to the civilization of humankind throughout history.[4]

And we can cross the whole of Asia and find the Negro again, for, when, in far-off Japan, the ancestors of the modern Japanese were making their way northward against the Ainu, the aborigines of that country, the leader of their armies was Sakanouye Tamuramaro, a famous general and a Negro.

The source of this description is not stated,[5] but no older literature has of yet been found that describes Sakanoue Tamuramaro as black.

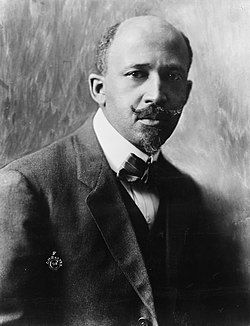

In 1915, W.E.B. Du Bois, an American civil rights leader, included Sakanoue no Tamuramaro in his list of great black rulers and warriors and introduced him in his book "The Negro".[6]

After World War II

[edit]In 1946, Beatrice J. Fleming and Marion J. Pryd published "Distinguished Negroes Abroad." This was the first detailed introduction of Tamuramaro as a black man. The portion of this work that talks about Tamuramaro is in the form of a fictional Japanese man telling his two sons about Tamuramaro's exploits in front of the Tamuramaro statue at Kiyomizu-dera.[1]

"Haruo ," advised the father, "You have been educated in Europe and America. Take the best of what you have learned, but always remember to regard a man as a man, irrespective of race or color. Japan did not enslave her captives nor the aliens on her shores in the time of Tamuramaro. True these were relegated to the lowly estate of serfdom but opportunities to rise and succeed were ever present. Sakanouye Tamuramaro was a Negro and true to his kind he proved himself a worthy soldier. He fought with and for us. And for is, too, he won the mighty victory. To us, therefore, he is not an alien; we think of him not as a foreigner. He is our revered warrior of Japan!"[7]

In 1946, Tamuramaro was featured as a black man in "The Negro in Our History" (by Carter G. Woodson and Charles Harris Wesley) and "World's Greatest Men of Color" (by Joel Augustus Rogers).[5]

The image of the "Statue of Tamuramaro at Kiyomizu-dera" featured in "Distinguished Negroes Abroad" was concretized in "Black Shogun of Japan Sophonisba: Wife of Two Warring Kings and Other Black Stories from Antiguity" published by Mark Hyman in 1989.[7]

"As seen in the temple where he has [sic] honored, Maro's [sic] statue was taller than his fellow contributors. His hair was curly and tight, his eyes were large and wide-set and brown. His nostrils were flared, his forehead wider, his jaws thick and slightly protruded"[7]

From the late 1980s to the 1990s, the legend of Tamuramaro, based on the descriptions in "Distinguished Negroes Abroad" and "Black Shogun of Japan Sophonisba," became well known among those who spread information that he was black. The statue of Tamuramaro in Tamura-do Hall(Kaizan-do Hall), which enshrines Tamuramaro at Kiyomizu-dera, was made after a fire in 1633, and naturally has no black characteristics. It is unclear whether Mark Hyman is referring to this statue or a different one.[7]

In 1980, the American-produced TV drama "SHŌGUN" was broadcast in many countries, including Japan, and this rumor temporarily gained popularity, but since information networks were not fully developed at the time, this information rarely reached Japan.[8]

21st century

[edit]In the 21st century, the theory that Sakanoue no Tamuramaro was black continues to be believed by some figures, such as American lecturer Runoko Rashidi.[5][7] and by online communities.[7] Cultural anthropologist Yutaka Nakamura reports an experience that took place between 2002 and 2004, when a black Muslim man living in the Harlem area claimed that "Sakanoue Tamuramaro was African."[9] However, until at least 2007, this discourse had rarely been featured on Japanese internet blogs.[10]

In 2024, the theory gained popularity again after a remake of the 1980 TV drama Shōgun was produced and broadcast in the United States.[8] In addition, the game "Assassin's Creed Shadows" features a character who is a legendary black samurai, modeled after Yasuke, who visited Japan from Africa during the Sengoku period and was liked by Oda Nobunaga and was hired as his retainer. When people who felt uncomfortable with the setting looked into it, they found various papers and articles related to black theory.[11][12][13]

With the development of information networks and the spread of websites, social media, and videos around the world, many Japanese have finally become aware of this situation. New web articles on this theory have been created in Japan, and some Japanese have begun to communicate about this theory on social networking sites. This does not support the theory that they were black. These stories do not support the theory that they were black. Because they are old stories, there is little evidence and no way to verify them, so they are not believed or taken seriously in Japan, but they are treated as a theory that is believed in some parts of the world.[14]

Associated proverb

[edit]The suggestion Sakanoue no Tamuramaro was black has sometimes been accompanied by the alleged Japanese proverb "For a Samurai to be brave, he must have a bit of Black blood" exists in Japan.[5] There is no such proverb in Japan, and it is unknown when or who uttered it.[15]

According to "Observations sur une note du docteur Maget relative aux races japonaises" (by M. DE QUATREFAGES) published in the French academic journal "Bulletins de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris" in 1883, Dr. Georges Maget, a military surgeon of the French Navy, wrote in a letter, along with various speculations about the race of the Japanese, the sentence "Un proverbe japonais dit que, pour faire un bon soldat (samourar), il faut avoir une moitié de sang noir dans les veines" (English: "A Japanese proverb says that to make a good soldier (samurai), you must have half black blood in your veins").[16] The February 24, 1877 issue of the Japan Weekly Mail carried a three-page article criticizing Maget's claims regarding the racial origins of the Japanese people, suggesting that he may have made similar statements in the past.[17]

Background

[edit]The theory is not believed at all in Japan and is not well known, but has seen wide acceptance in the black community. This may be due to the following reasons.

Favorable feelings toward Japan among the black community

[edit]W.E.B. Du Bois, one of the first to introduce the Tamura Maro black theory, is known for his deep ties to Japan. He was impressed by the strength of the Imperial Japanese Army in the Russo-Japanese War and encouraged by the victory of colored races over whites.[18] He later cooperated with Yasuichi Hikita's "Negro Propaganda Operations" and came to Japan. This was because he had a favorable reaction to the racial policies of Imperial Japan. [19] The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, of which he was one of the co-founders, strongly opposed the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, and welcomed back Japanese Americans released from internment camps after the war. He is known for arranging jobs and inviting people to church.[20]

In 1919, the Imperial Japan proposed an abolition of Racial Equality Proposal. Blacks in the United States supported it, but President Woodrow Wilson did not pass it because it was not unanimous. This was one of the factors that led to the outbreak of tragic racial conflicts, including the Red Summer.[21]

In this way, there were many black people who had favorable feelings towards Japan. The legend of Tamuramaro was typically expressed in the accounts of "Distinguished Negroes Abroad" and was linked to the widespread belief among black people that "Japanese people are less discriminatory than white people," a belief that was common during and after World War II.[22]

Existence of theory that black people settled in ancient Asia

[edit]

The theory that black people settled in Asia, including Japan, has been put forward many times. American anthropologist Roland Burrage Dixon argued that (under now-outdated racial groupings) the Japanese were a mixture of Proto-Australoid and Proto-Negroid, and that the Japanese show Negrito (a dark-skinned ethnic group living in Southeast Asia and New Guinea) characteristics.[5] Senegalese historian and anthropologist Cheikh Anta Diop also argued that the Asian ‘race’ was a mixture of black and white races.[5] Subsequent research has revealed that 35% of Japanese people have the Y-chromosome haplogroup D, which is found in almost 100% of Andaman Islanders who are part of the Negrito grouping. It has been suggested that the two ethnic groups may be closely related.[23][24]

It is now generally agreed that the Negrito ethnic groups are more closely related to Australasian ethnic groups than African ethnic groups.[25][26]

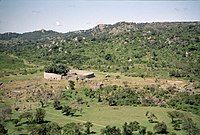

Wariness of historical revisionism

[edit]

Both historically and in the modern day, Black people have feared that their history was being hidden or falsified by outsiders, especially white people. This fear is not unfounded; when the Great Zimbabwe ruins were first discovered, Western scholars did not acknowledge that they were built by black people, and continued to insist for many years that they were built by Phoenicians, Arabs, or Europeans.[22] Similarly, the theory that Tamuramaro was a black man was bolstered by suspicions that Tamuramaro's true identity had been intentionally hidden due to a white-centric view of history.[9][22]

Some proponents of the black theory believe that Japanese people, as members of a monoethnic nation, would feel ashamed that Tamuramaro, a hero, was black.[10] Some people suspect that the statue of Sakanoue no Tamuramaro is not usually open to the public, based on the history of black Madonna statues being hidden in secluded places in Europe, and that Kiyomizu-dera is intentionally trying to hide the characteristics of the statue of Sakanoue no Tamuramaro.[10]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Russell 2008, p. 16

- ^ ja:伊藤信博 (Mar 2005). 桓武期の政策に関する一分析 (1). 言語文化論集 (Thesis) (in Japanese). Vol. 26. 名古屋大学大学院国際言語文化研究科. pp. 3–40. doi:10.18999/stulc.26.2.3. hdl:2237/7911. ISSN 0388-6824. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ^ ja:高橋崇 [in Japanese] (1986). 坂上田村麻呂. 人物叢書 (in Japanese) (新稿版 ed.). ja:吉川弘文館. pp. 3–6. ISBN 9784642050456.

- ^ Alexander Francis Chamberlain (1911). "The Contribution of the Negro to Human Civilization". The Journal of Race Development. 1 (4): 482–502. doi:10.2307/29737886. ISSN 1068-3380. JSTOR 29737886.

- ^ a b c d e f "The World of Sakanouye No Tamuramaro: Black Shogun of Early Japan". Atlanta Black Star. 7 September 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ^ The Negro,1915,p.84. Cosimo. January 2010. ISBN 978-1-61640-367-6. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Russell 2008, p. 17

- ^ a b William Spivey (2024-03-08). "Where Are The Black People in 'Shogun'?". LEVEL man. Retrieved 2024-08-18.

- ^ a b 中村, 寛 (2013). アーカイヴへの不満: アフリカ系アメリカ人ムスリムにおけるアイデンティティをめぐる闘争(<特集>アイデンティティと帰属をめぐるアポリア-理論・継承・歴史) [Discontent with the Archive: African American Muslim Identity Struggles(<Special Issue>Aporias around Identity and Belonging: Theory, Heritage, and History)]. 文化人類学 (in Japanese). 78 (2): 225–244. doi:10.14890/jjcanth.78.2_225.

- ^ a b c Russell 2008, p. 19

- ^ Mike Nelson (15 May 2024). "How Assassin's Creed Shadows Will Blend Two Distinct Adventures in One". Xbox Wire. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ Russell 2008

- ^ Neil Turner (2024-01-01). "Black Japanese: the African Diaspora in Japan". Perspectives in Anthropology. Retrieved 2024-08-19.

- ^ 堀江宏樹 (2024-07-09). "アメリカの公民権運動に利用され、欧米で流布した「坂上田村麻呂=黒人説」とは【古代史ミステリー】" [What is the theory that Sakanoue no Tamuramaro was black, which was used in the American civil rights movement and spread in the West? [Ancient History Mystery]]. 歴史人 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-12-01.

- ^ "Georges Maget Quotes". quote.org. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ Bulletins de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris. p. 653.

- ^ Japan Weekly Mail. pp. 106–109.

- ^ Lewis, David (4 August 2009). W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography, Henry Holt and Co., Single volume edition, updated, of his 1994 and 2001 works, p.597. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-8805-2. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ^ Gallicchio, Marc S. (18 September 2000), The African American Encounter with Japan and China: Black Internationalism in Asia, 1895-1945, University of North Carolina Press, p. 104, ISBN 978-0-8078-2559-4, OCLC 43334134

- ^ レジナルド・カーニー (1995). 20世紀の日本人―アメリカ黒人の日本人観 1900-1945 (in Japanese). 山本伸(訳). 五月書房. ISBN 9784772702348.(Original:Reginald Kearney, African American views of the Japanese: solidarity or sedition?, State University of New York Press, 1998)

- ^ Paul Gordon Lauren (September 1995). 国家と人種偏見 (in Japanese). Translated by 大蔵雄之助. TBSブリタニカ(阪急コミュニケーションズ). pp. 151–152. ISBN 9784484951126.

- ^ a b c Russell 2008, p. 18

- ^ Kumarasamy Thangarajlain; Lalji Singh, Alla G. Reddy; V.Raghavendra Rao; Subhash C. Sehgal; Peter A. Underhill; Melanie Pierson; Ian G. Frame; Erika Hagelberg (21 January 2003). "Genetic Affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a Vanishing Human Population". Current Biology. 13 (2): 86–93. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01336-2.

- ^ Atsushi Tajima; Masanori Hayami; Katsushi Tokunaga; Takeo Juji; Masafumi Matsuo; Sangkot Marzuki; Keiichi Omoto & Satoshi Horai (2 March 2004). "Genetic origins of the Ainu inferred from combined DNA analyses of maternal and paternal lineages". Human Genetics. 49 (4): 187–193. doi:10.1007/s10038-004-0131-x. PMID 14997363.

- ^ Thangaraj, K.; Singh, L.; Reddy, A. G.; Rao, V. R.; Sehgal, S. C.; Underhill, P. A.; Pierson, M.; Frame, I. G.; Hagelberg, E. (2003). "Genetic affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a vanishing human population". Current Biology. 13 (2). Current Biology: 86–93. doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01336-2. PMID 12546781. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Stock, J. T. (2013). "The skeletal phenotype of "negritos" from the Andaman Islands and Philippines relative to global variation among hunter-gatherers". Human Biology. 85 (1–3): 67–94. doi:10.3378/027.085.0304. PMID 24297221. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Russell John G. (Mar 2008). "Excluded Presence: Shoguns, Minstrels, Bodyguards, and Japan's Encounters with the Black Other". ZINBUN. 40. Jinbun kagaku Kenkyusho, Kyoto University: 15–51. doi:10.14989/71097. hdl:2433/71097. ISSN 0084-5515.

See also

[edit]- Sakanoue no Tamuramaro

- Legend of Sakanoue no Tamuramaro

- Tamura story

- That he was of Emishi origin

- That he was born in Oshu