Pellegrini–Stieda syndrome

| Pellegrini–Stieda syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome. Also visible is a fracture of the patella. |

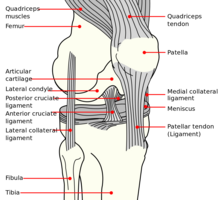

Pellegrini–Stieda syndrome (also called Stieda disease and Köhler–Pellegrini–Stieda disease) refers to the ossification of the superior part of the medial collateral ligament of the knee. It is a common incidental finding on knee radiographs. It is named for the Italian surgeon A. Pellegrini (b. 1877) and the German surgeon A. Stieda (1869–1945).[1] While the eponym is credited to Pellegrini and Stieda, the condition was first discovered by Köhler in 1903, before any namesakes. Pellegrini-Stieda combines the aforementioned radiographic findings and concomitant medial knee joint pain or restricted range of motion.[2]

In 1905, Pellegrini described the first reported case of calcification, involving the collateral ligament of the knee in a 36-year-old man examined at the Department of Surgery in Florence on March 13, 1905.[3] Later, Stieda observed calcification on the medial side of the distal femur, which was described in 1908.[3] The proposed origin of calcification on the medial side of the knee is diverse. It can be more complex than either Pellegrini or Stieda proposed. [3]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Most patients are asymptomatic from this ossification, and small percentage experience medial knee pain (with or without restricted knee range-of-motion and knee joint swelling), defined as Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome.[2]

In cases, untreated Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome could lead to restricted knee joint range-of-motion and contracture developing into gait abnormalities, decreased activities of daily living, and chronic pain. Some studies have suggested poor surgical outcomes with high recurrence rates or ligamentous defects with large lesion excisions requiring further surgical reconstruction.[2]

The calcification seen on imaging represents the ossification of the medial collateral ligament which typically does not develop until approximately three weeks after the initial injury.[2]

Pain and local swelling in the medial aspect of the knee are the two first symptoms following an injury like traumatic synovitis. The pain and disability will increase after a few weeks or months.[4]

Cause

[edit]Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome is an insult to the medial collateral ligament (MCL), causing damage and acute inflammation that sets into motion and delays ossification.[2] This insult is described as a macro trauma causing valgus stress with disruption of the MCL fibers. This condition is usually associated with sports activity.

However, micro-repetitive trauma from therapeutic manipulation of a restricted knee joint or post-surgical rehabilitation are possible etiologies of Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome.[2] In some cases, Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome has been seen in patients without knee trauma but accompanies spinal cord injury or traumatic brain injury.[2]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The initial injury to the knee, whether resulting from macro- or repetitive microtrauma, leads to the same result: calcific ossification of the soft tissue structures surrounding the medial femoral condyle.[2] This sprain or tear in the medial collateral ligament leads to inflamation of the area. The bodies inflammatory response lead to an immune response to try to repair leading to an abnormal healing process. The abnormalities lead to a disposition of calcium at the tear site of the medial collateral ligament which over time hardens to form a bony mass called heterotrophic ossification. As healing continues, the fibrocartilage or other disorganized tissue becomes calcified, and over weeks to months, it ossifies, forming bone-like material at the MCL attachment site.[5]

The origin of calcification remains under debate but proposed origins are:

- deep medial/tibial collateral ligament

- superficial medial/tibial collateral ligament

- medial patellofemoral ligament

- medial gastrocnemius

- adductor magnus

- vastus medialis.[4]

In some cases associated with spinal cord injury or traumatic brain injury, neurogenic precipitation of ectopic bone formation can occur by humoral, neural, and local factors, including tissue hypoxia, hypercalcemia, changes in sympathetic nerve activity, prolonged immobilization, and subsequent mobilization.[2]

Diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosis is typically made on radiographs demonstrating the Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome sign accompanied by pain or restriction of range-of-motion of the knee joint.[2] Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome sign is typically described by a longitudinally linear opacity, which is a process that is describes characteristic of calcification in the soft tissue located medial to the medial femoral condyle.[2] This calcification seen on imaging represents the ossification of the medial collateral ligament, which typically does not develop until approximately three weeks after the initial injury.[2]It is important to note to distinguish this radiographic finding from that of a medial femoral condyle avulsion fracture, which is an injury in which a pulling force of a tendon or ligament fractures away a piece of the bone from its attachment site.[2]

Alternative classification syndrome for Pellegrini-Stieda lesions of Type 1 through Type 4 based on their location:[2]

- Type 1- is referred to as a beak-like appearance and describes the ossification arising from the femur and extending inferiorly in the medial collateral ligament.

- Type 2-is defines a tear-drop pattern, localized within the medial collateral ligament without any attachment to the femur.

- Type 3-presents as an elongated ossification superior to the femur lying in the distal adductor magnus tendon.

- Type 4-is also characterized as a beak-like appearance arising from the femur. However, there are some cases where this ossification extends into both the medial collateral ligament and adductor magnus tendon. In then, the original attribution of the syndrome to the medial collateral ligament may now be outdated as many publications have suggested concomitant and even sometimes preferential involvement of the adductor magnus tendon, medial head of the gastrocnemius, or medial patellofemoral ligament.[2]

Treatment

[edit]Symptom duration is typically five to six months as the ossified lesion matures. The severity of the pathology will dictate the treatment plan.

- Mild and moderate cases are usually managed conservatively with non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAID),

- corticosteroid injections

- Range-of-motion exercises.

Severe refractory cases, however, are considered candidates for surgical excision of medial collateral ligament calcifications.[2]

Prognosis

[edit]Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome can be developed In different stages of life, most likely in the middle life from 25-40 years old. There doesn't seem to be any sign of hereditary factors at the moment, it is shown that Pellegrini-Stieda Syndrome is a result of a knee injury and ossification of the knee after a certain amount of time.

When a full range of motion in the knee is attained, and the athlete does not feel any form of pain, they can resume their activities. It is also important that the range of motion is symmetric on both sides. Also, the muscles, Quadriceps, and Hamstrings, have fully recovered.[4]

Epidemiology

[edit]The Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome is a relatively infrequent phenomenon and is commonly associated with sporting injuries. Pellegrini-Stieda Syndrome Is more frequent in the males between 25 and 40 years of age. Direct trauma or in a distant site (skull or spine), repetitive trauma, or after an overstretching injury to the medial collateral ligament and joint capsule can result in an avulsion of the medial femoral condyle or a tear of ligaments, tendons. Ossification could happen within 11 days to 6 weeks after post trauma. A network of the new bone formation around the periphery of the mass of the medial condyle is formed in 6 to 8 weeks. Duration of the condition is usually about 5 to 6 months.[4]

After a while, the phenomena could occur: the inflammation subsides with partial or complete resorption of the calcium salts, or the mass becomes ossified and may be connected by a pedicle to the femoral condyle.[4]

Research directions

[edit]There have been several cases studies presented for Pellegrini-Stieda Syndrome. Many case studies present themselves in similar fashion with an injury and after a certain amount of time the injured knee produces ossification resulting in immobilization of the knee.

For example, a 26-year-old male was involved in a high energy road traffic collision. He was ejected from the car, sustained a signicant head injury and a left knee injury. On initial examination it was noted that there was some laxity on stressing the MCL. The initial radiographs did not show any bony injury of the left knee. He was referred to the senior author 3 months after the initial injury with ongoing pain and a reduced range of movement. Examination revealed a Exion deformity which was painful. Radiographs revealed marked heterotypic ossification in the region of the origin of the MCL, the so called Pellegrini-Stieda lesion.[6]

A 51-year-old male patient who 12 years ago presented traumatic twisting of the right knee; a rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament was diagnosed by MRI, which was managed conservatively with NSAID, immobilization and physical therapy with complete resolution. Five years later the patient began having pain in both knees, mainly in the right, that was exacerbated with physical activity and improved with rest at the beginning of treatment again. Subsequently, it became permanent and for this reason various types of NSAIDs were prescribed without having achieved pain control for several years. A radiography was later reported showing the knees calcification of the medial collateral ligament in its proximal portion, in addition to a decrease in the medial femorotibial space. At the right side in the coronal acquisition with T1 information of the knee becomes evident an ossification in the proximal end of the medial collateral ligament, in relation with an old-injury, configuring a Pellegrini–Stieda lesion. [7]

Lastly, another case was presented to investigate the origin of the Pellegrini-Stieda lesion using radiography. They used six non-paired fresh-frozen cadaveric knees. A surgical approach to the medial side of the knee was performed using the layered approach. X-Ray analysis was performed by measuring the distance from the proximal part of the marking to the medial tibial plateau, multilayered views and comparison to the original X-rays by Pellegrini-Stieda. Conventional X-ray of the knee could not reproduce the historic distinction between the Pellegrini and the Stieda origins for the Pellegrini-Stieda lesion. There has been debate where the origin of the Pellegrini-Stieda Lesion remain lively, although recent studies have suggested other possible origins, such as the Adductor Magnus muscle in addition to the MCL. There have been limitations to present studies like limited number of specimens, more reliable results, questionable X-ray information as the technique used by Stieda and Pellegrini have been shown to have a lack of detail as they are historic publications.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Mohammad Diab (1999). Lexicon of Orthopaedic Etymology. Taylor & Francis. p. 380. ISBN 9789057025976.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Weaver, Martin; Sherman, Andrew L. (2024), "Pellegrini-Stieda Disease", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30570968, retrieved 2024-10-30

- ^ a b c d Somford, Matthijs Paul; Lorusso, Lorenzo; Porro, Alessandro; Loon, Corné Van; Eygendaal, Denise (2018). "The Pellegrini–Stieda Lesion Dissected Historically". The Journal of Knee Surgery. 31 (6): 562–567. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1604401. ISSN 1538-8506 – via JOKS.

- ^ a b c d e "Pellegrini-Stieda Syndrome". Physiopedia.

- ^ Mulligan, Susan A.; Schwartz, Martin L.; Broussard, Marc F.; Andrews, James R. (2000). "Heterotopic Calcification and Tears of the Ulnar Collateral Ligament". American Journal of Roentgenology. 175 (4): 1099–1102. doi:10.2214/ajr.175.4.1751099. ISSN 0361-803X.

- ^ "Good result after surgical treatment of - ProQuest". www.proquest.com. ProQuest 220019885. Retrieved 2024-11-05.

- ^ Restrepo, Juan Pablo; Molina, María del Pilar (2016-07-01). "Pellegrini–Stieda syndrome: More than a radiological sign". Revista Colombiana de Reumatología (English Edition). 23 (3): 210–212. doi:10.1016/j.rcreue.2016.12.004. ISSN 2444-4405.

Further reading

[edit]- Altschuler, Eric L.; Bryce, Thomas N. (December 2006). "Images in clinical medicine. Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (1): e1. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm040406. PMID 16394294.

- Wang, JC; Shapiro, MS (1995). "Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome". American Journal of Orthopedics. 24 (6): 493–7. PMID 7670873.